Caitlin Doughty's Blog, page 28

July 8, 2017

ICONIC CORPSE: Sweet Little (Haunted?) Rosalia Lombardo

CONIC CORPSE: Sweet Little (Haunted?) Rosalia Lombardo

July 5, 2017

My First Death: The Indelible Scent of Chemicals and Baby Powder

“My father died when I was two months old. He was in a car accident; obviously I don’t remember. But there are pictures of his funeral and believe he had a baby blue casket with white trim Which is very odd!”

Vicky DeMercer laughed as she shared this detail with me. Her laughter echoed against the white walls around her, and intermingled with the muffled sounds of ambient conversation. Now and then I heard the sound of a car or motorcycle roar and disappear in the distance; the front door fall shut with a soft rattle and thud.

Skyping me from the lobby of the studio in Honolulu, Hawai‘i where she teaches and takes dance classes, Vicky’s open, eager, but thoughtful tone made it feel like the perfect place to talk about death. No big thing, just two pals talking about funerals while Lycra-clad dancers sipped water and chatted about the next training or masterclass. Really, it’s the way life ought to be.

Of good ol’ midwestern American and Native Hawaiian descent, Vicky was raised on the Big Island of Hawai‘i, in a small town in North Kohala called Hawi (pronounced ha-vee).

“Growing up in a small plantation town on the Big Island, there’s a lot of kids and a lot of old people. So people are always being born and people are always dying, there’s not really a lot of people in-between.”

Death was never a stranger to Vicky. Even beyond her father’s early death, life in North Kohala didn’t shield her from the dead. But what was there to shield her from? As a young child, graves, cemeteries, funerals were not scary but mundane.

From graves still residing on family land to playing in the cemetery when church got too dull, Vicky’s very ordinary Big Island childhood was dotted with very ordinary dealings with death.

“In our town we have the 7th Day Adventist Church, the Jodo Mission, and the Catholic Church all right next to each other,” she explained. This made for a lot of different kinds of funerals in the community.

“So for me, growing up I had actually been to more funerals than weddings. The amount of funerals to birthday parties,” she said doing that “balancing the scales” motion with her hands, “was pretty equal.”

And though death didn’t phase or frighten her as child, she does have strong memories of the first time death impacted her life. When Vicky was about 3-years-old her godfather died.

“I would spend the weekends at my godmother’s house when I was maybe like three or four-years-old. She had these two twin beds that she would push together so my sister and I could sleep next to each other, and she would sleep on the outside. I remember waking up one morning and my godmother was like, ‘Stay in the room. You and your sister are not allowed to come out.’ Because overnight my godfather had passed away. He slept in a different room.

She made us stay in the room until his body was carried out by – I don’t know, the hospital? The morgue? There are no undertakers in my town. I don’t know who took the body out.”

Did you understand what happened to your godfather?

“I knew what death was since my father had died when I was a baby. But this was my first actual experience with death.”

So it was explained to you?

“I want to say that it was explained to me. And since it was explained to me, even though I don’t remember it being explained to me, by the time I was three or four I understood.”

Vicky paused as if running that explanation through her head to see if it made sense. As one of those unspoken lessons we absorb as wee, little children – like sugar tastes good and don’t drink (a lot of) the bath water – Vicky absorbed an understanding of death.

“I understood that death was when you have nothing left in your body – you cannot animate your body anymore. We were raised Catholic; God is taking your spirit, God is taking you home. [When you die] the only thing that’s left in your body is your organs and bones.

I always understood that at some point I’m going to die. And it wasn’t necessarily something I was scared of, I was just scared of how I was going to die.”

We momentarily shifted into a rapid-fire discussion of our shared fear of drowning under bizarre circumstances.

“I slipped and fell into the sink. And now I’m dead.”

“Oops. I fainted into this bowl of juice. Now I’m dead.”

And of course being pounded to death by the Hawaiian surf or drowning in an underwater cave. I had a similar conversation with Caitlin in a bar in Honolulu a few years ago.

Apparently death positive people who have lived in Hawai‘i are afraid of water?

After that brief (but terrifying) digression, we carried on.

What was your reaction to to your godfather’s death?

Vicky laughed. Despite her rather mature-for-a-three-year-old understanding of death, she still had a child’s reaction.

“When we found out he was dead through the whispers of what was going on that morning, I just thought, ‘OH. So-and-so’s rabbit just died and when they found the rabbit, the eyeballs were rolled-up in the back of the head!’

So I was asking my godmother, ‘WERE HIS EYEBALLS ROLLED-UP IN THE BACK OF HIS HEAD?’

My godmother, who was obviously doing her best to handle the situation, who had been married to my godfather for 50-plus years, is dealing with her husband’s death, and there’s this little girl asking, ‘Were his eyes rolled backwards Auntie? Is that how you knew he was dead?’”

Vicky describes a rather swift, matter-of-fact acceptance of her godfather’s death. No panic or anguish, rather an understanding of an end.

“I knew that I wasn’t going to be able to get him coffee anymore. I knew I wasn’t going to be able to clean the hair out of his electric razor anymore.

To me, it was just like, ‘Oh. So he dead.’”

The next thing she remembers is her godfather’s funeral.

“Our Catholic church was called Sacred Heart, like a billion other Catholic churches. Our Sacred Heart church in Hawi has this beautiful altar with brass [pieces]. The big brass baptismal bowl, the wooden altar made from eucalyptus – my godfather made all of those. And to me, seeing his coffin up against his beautiful pieces of handiwork, it was almost garish to me.

Not that I could comprehend that as a three-year-old! But looking back on it.”

Of course, what imprinted on Vicky at her godfather’s funeral, and what has lingered with her to this day, is a detail that a lot of “polite” adults are taught to ignore.

“When I saw him just laid out [at the church], the smell is what really resonated with me. I just remember the smell of his body.”

How did he smell?

Vicky paused, choosing her words, turning over the intangible in her memory.

“I don’t know how else to say it except that it’s a very western, dead body smell. Like it was this odd chemical-baby powder kind of smell. To this day, whenever I go to a funeral and I see an open casket, and it’s a western-style funeral, the first thing that always hits me is the smell. The weird chemical-baby powder smell.

And I remember looking at him, and I was like, ‘Can I touch him?’ And I touched him, and he was cold.”

But Vicky’s experience at her godfather’s funeral was not devoid of emotion.

“I saw lots of people crying. I was like, ‘Why are they crying? He’s just dead.’

And then I was mad because I couldn’t sit next to my godmother. I always sat next to her during church. Why couldn’t I sit next to her?

Her daughter and her grandkids were up there [sitting] with her, and I was sitting there thinking, ‘But I play with [the grandkids] all the time! I see her more than they do! I was in the house when he died!’

All of these little things at my first funeral — I was irritated, bored, and upset. It was very upsetting to me for very selfish reasons!”

Ah, the candor of a little girl. Honestly, not much of that candor is lost in 30-something Vicky. Only now, it’s candor with a deepening of feeling.

Vicky continued, regarding her demeanor at the funeral.

“Of course, that was the mind of a three or four-year-old who’d only known someone consciously for a few years. [My godfather] was a staple of the community. He was one of the older Filipino men in the community. He was a church goer, he was a church supporter, and he was a remnant of those bygone plantation era days when people really took care of each other.

No tears were present because I didn’t have anything to feel sorry about. I think that I had a better idea of loss than I did of love. The concept of love was not lost on me, but it was much easier for me to understand the concept of death, the concept of non-being. His body was there, his being was not.”

As Vicky and I wrapped up and our conversation devolved into catching up about work and family, we somehow wound our way back to cemetery talk and the time Vicky found herself digging into the graves of her father and grandmother.

With an exasperated roll of the eyes that most people reserve for when their partner forgets to take out the trash, she regaled me with the story of how her uncle ended up haphazardly buried on top of her father. “Buried” being a relative term.

“On top. And I don’t mean they had digging tools. I mean the cardboard box [with the remains in it] still addressed to Uncle Carl*, with Uncle Ned’s ashes in it. They removed a piece of grass, made a hole, and put the grass right back on top.”

Instant grave.

The rest of her story involved her distraught mother, shovels and picks, three half-gallon buckets of dirt from her family’s backyard, the discovery of more rogue ashes buried on top of her grandmother’s grave, and Vicky digging up and reburying cremated remains in a cemetery in North Kohala at dusk.

“My husband, who was not there, thought it was a matter of calling the church that maintains the cemetery and getting everything moved – very clean cut. But I was like, ‘It’s Kohala. It’s not like that at all.’”

And it was that straightforward, no-nonsense regard to death and the dead that punctuated Vicky’s telling of her godfather’s funeral and her uncle’s (re)burial. A ‘final resting place’ was never a mystery to me,” she said.

As Vicky puts it, her understanding of death “evolved” from “irritated to heartbroken” when she was able to comprehend loss, but death never filled her wth dread.

Just because a person was dead, their “being” gone, didn’t make them any less a part of the community. From an outside perspective, it’s not flippant, it’s not casual, it’s merely how people move forward – you’re still my neighbor, you’re just dead.

*Names of Vicky’s family have been changed to protect their privacy.

Louise Hung is an American writer living in Japan. You may remember her from xoJane’s Creepy Corner, Global Comment, or from one of her many articles on death, folklore, or cats floating around the Internet. Follow her on Twitter.

My First Death: The Indelible Scent of Chemicals and Baby Powder

June 27, 2017

Paying My Respects to the Most Loyal Cat in Japan

We were all a bit cranky by the time we found the graveyard.

Don’t get me wrong, Hagi is lovely. It’s one of those Japanese towns that’s nestled between the sea and the mountains in the Yamaguchi prefecture, where history and modern day blend harmoniously together.

From the 7-Elevens to the renowned historic pottery shops, the entire town has its eyes turned toward the ruins of Hagi Castle. But just because you can walk those glorious Edo era streets (c. 1600-1868) with a glorious Edo era map doesn’t mean you can’t get gloriously Edo era lost.

Getting lost in Japan is not difficult, as the organization of streets isn’t always the most intuitive for westerners. Even life-long residents of places like Tokyo will tell you that you “just have to know” where certain streets bend, split, or disappear. I’ve lived in Japan for over two years now, and if you give me a random address and tell me to “Go find it girl!” I’ll ask you to pack me a sandwich because I’ll be gone for a while. (Yes, yes, Google Maps, but unless you’re a skilled tracker, a series of directions that say, “Turn left, turn left, turn right, now walk on water,” only goes so far.)

So with my mother-in-law, her friend, and my husband in tow, I had somehow been put in charge of finding our cemetery destination after our trip to the castle ruins. My first mistake was bragging about my “Labrador powers” AKA my uncanny sense of direction. I don’t even know if Labradors have a good sense of direction.

After wandering around and around and around Hagi’s streets for (a not unpleasant) afternoon (in my opinion), my little group’s sense of adventure was waning.

“How is this another special graveyard?” My mother-in-law asked. I chose not to hear the eye-roll in “another.”

“It’s the Hachiko cat grave!” I said.

That’s what I’d been calling the goal of our quest, the Hachiko Cat grave. It’s actually a misnomer in a lot of ways, but calling it “The Grave Where the Guy’s Loyal Cat Died” is just a mouthful. The grave is not actually the cat’s grave, but the cat’s owner’s grave. So says legend. And Hachiko, as many of you may know, is not actually the cat, but the name of one of Japan’s most beloved symbols of loyalty: Hachiko the dog.

Hachi dog via terrazzo on Flickr.

I won’t go too far into Hachiko’s story, as that pup’s had more than his fair share of Internet fame – like here, here, and here, not to mention that movie with Richard Gere.

Basically what you need to know is that Hachiko was a loyal Akita dog that belonged to a professor who lived in Shibuya, Tokyo in the early part of the 20th century. Everyday Hachiko would walk his master to the Shibuya train station, see him off to work, then wait for him to return. However one day, in 1925, his master died of a brain hemorrhage and never returned to the station.

As the story goes – and Hachiko has surely become the stuff of legends – Hachiko continued to wait at Shibuya train station for 10 years, waiting for the master that would never return. He eventually died and is now immortalized as a statue at Shibuya station. You can visit Hachiko’s taxidermied body at the National Museum of Nature and Science in Ueno Park.

Japan loves myths of loyalty and mortality, bonus points if that myth involves animals.

Enter the kitty.

When the Japanese warlord Mori Terumoto, of the powerful Mori clan of Hagi, died in 1625, his loyal samurai, Nagai Motofusa died too (likely by suicide). As the sign at his grave says, he died because, “He felt a deep gratitude towards his lord.” Talk about loyalty.

But when Nagai died, he left behind his “beloved cat”. That cat, also probably feeling a “deep gratitude” towards Nagai, supposedly refused to leave his master’s grave for 49 days. It is said that the cat was observing the Buddhist Houyou memorial ceremony to mourn the dead.

After 49 days, the cat couldn’t take it anymore, bit his tongue, and bled to death on Nagai’s grave. Leave it to a cat to take the most metal route to death.

According to Hagi legend, that night all the cats of Hagi raised their collective feline voices in honor of Nagai’s cat.

Feeling sorry for the kitty – and probably hoping to quiet Hagi’s yowling cats – a priest at Tenjuin Temple (which once stood at the gravesite) decided to perform memorial rites for the cat.

As soon as he did, the Hagi cats stopped wailing.

And though the temple is gone, the nearby temple, Unrinji, keeps the memory of Nagai’s cat alive by maintaining a special devotion to cats. Called the “Cat Temple” or nekodera in Hagi, the temple is chock full of cat artwork, statues, and blessings.

Furthermore, the area where Nagai’s house was once located has been dubbed “Cat Town”. It’s been said that ghostly meows were heard from Nagai’s house after his cat’s death, and to this day some say the forlorn ghost cat’s mews can still be heard in Cat Town.

Hagi takes a special pride in the story of their loyal cat. Granted “cat tourism” is not unusual in Japan (cat cafes, cat temples, cat islands can be found throughout the country), but there is a sort of reverence for cats in Hagi. With devotion and loyalty being part of the foundation on which Japanese culture was founded, combined with an enduring love of cats, Nagai’s cat checks all the boxes for the stuff of legends.

Plus it doesn’t hurt to have a local tale that rivals the Hachiko story (at least for those in the know). While most tourists visit Hagi to see the ruins of the castle, the cat story certainly appeals to Japanese affections. Hagi even has a cartoon cat mascot depicted in its tourist information center that enthusiastically highlights points of interest and how “EXCITING!” Hagi is.

If you’re so inclined, you can buy an adult sized, Hagi mascot cat costume for a few thousand US Dollars. No judgement, you do you.

Hagi costume.

But that day in Hagi I was not in search of cats, I was in search of Nagai Motofusa’s grave. While the temple is gone Nagai’s grave, as well as the graves of Mori Terumoto and wife, remain to this day.

After all the wrong turns, and terrorizing Hagi locals with my crappy Japanese (Crapanese), we finally stumbled upon the tiny graveyard. Behind a section of white wall, marked by only a small sign, in what looked like someones backyard, we found the historic graves.

Originally the site of Mori Terumoto’s home (destroyed in 1869), the property only holds three graves. The Mori graves, a significant clan in Japanese feudal history, are surrounded by a traditional basalt fence typically reserved for Shinto shrines, and are protected by a gate. For a warlord from a major family, the graves are stately but subtle; elegant but unassuming.

Just off the stone path that leads to the Mori graves, outside the basalt fence, sits Nagai’s grave.

Echoing the architecture of the Mori graves, it’s also rather unassuming, smaller than I thought it would be. The casual observer might not even know it’s a grave if it weren’t for the nearby placard.

Nagai grave.

It was on this spot that Nagai’s grieving cat supposedly bled to death hundreds of years ago.

While every legend of this sort is subject to the layers of embellishment and romanticizing that the ages heap upon it, on that bright day in Hagi, it was nice to enjoy what might have been.

Maybe Nagai really did have a cat he dearly loved. Maybe that cat did appear to be distraught when his master didn’t come home. Maybe somebody got confused and when a cat died near the grave, they conflated the cats and a legend was born. Maybe the people at the time needed such a story. Why look a good legend in the mouth?

And if nothing else, the story of Nagai’s cat led me to a cheery, little graveyard (for a warlord) that I might not have ever known existed. Death folklore (with cats!) plus historic graves? I’ll take it!

Leaving the Mori graveyard that afternoon, everyone’s spirits seemed to be lifted a bit. Not only had we achieved our (my) goal, but we’d also walked all over the Edo era. How often do you get to do that?

Back out on the street, watching a fleet of school children on bicycles ride by, our ragtag group seemed revived. Perhaps it was the promise of ice cream then the relief of sitting on a bus, but I’d like to think it was the experience of paying our respects at the crossroads of legend and history.

Louise Hung is an American writer living in Japan. You may remember her from xoJane’s Creepy Corner, Global Comment, or from one of her many articles on death, folklore, or cats floating around the Internet. Follow her on Twitter.

June 23, 2017

Reacting to My First EVER Video

June 20, 2017

American Trailblazers and Mexican Revolutionaries – Great Women in Death History

What is the Great Women in Death History series? There was a time not long ago when the responsibility of “death work” – caring for the dying, washing and preparing the body for burial, making preparations for the funeral – fell to women. With the advent of the medical and funeral industry, these roles were taken over by men who created a business of death, pushing women and their contributions to the side and largely forbidding their involvement in the roles and tasks they once filled. However, there were many women who defied the restrictive roles that society placed upon them, and even sought to redefine them – this series is about them. The unsung female heroes of death.

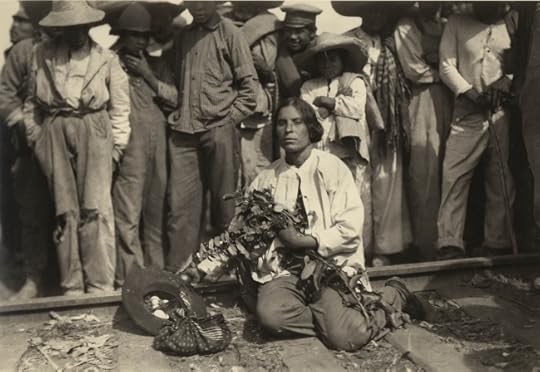

Photograph by Agustin Victor Cassola, 1915 photo of Maria Zavala, ‘La Destroyer’

Maria Zavala

Women played a vital role during the Mexican Revolution, as Las Soldaderas – women who followed their husbands, sons, fathers and brothers into war, often taking up arms and fighting on the front lines.

One notable soldadera was Maria Zavala, whom soldiers nicknamed La Destroyer. She began by doing welding work, and some historians have speculated that she may have aided the war effort by blowing up trains, but Zavala primarily became known for making sure that dying soldiers were given a good death. In some instances this meant she assisted them in dying a quicker and less painful death. Zavala used her knowledge of herbs to create remedies which lessened pain and eased the dying process and she also facilitated the soldier’s burials.

Lina D. Odou

Lina D. OdouAs the funeral industry and the beginnings of modern embalming began to emerge in the U.S., fifteen-year-old Lina Odou moved to London. It was here that she met mentor, Florence Nightingale and trained as a nurse. Shortly after, Odou would serve in the Red Cross in France.

During this time, it was not uncommon for women to suffer in silence because they refused to seek out the aid of a male physician, as maintaining their ladylike modesty was paramount in Victorian society. For this reason, caring for female corpses proved to be a challenge for the new and male dominated field of undertaking. “Over and over I heard mothers ask undertakers if they could not furnish women embalmers for their dead daughters,” Odou said. In response, she persuaded several established embalmers to train her, and when she moved to the U.S. she opened the Lina D. Odou Embalming Institute in Manhattan. She went on to become an advocate for women as death professionals and founded the Women’s Licensed Embalmer Association.

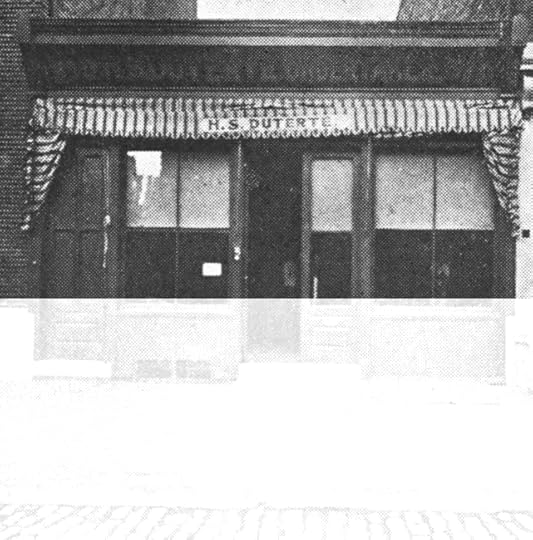

Duterte, pictured here with one of her children who died in infancy

Henrietta Smith Bowers Duterte

Born in 1817 into a well-established free-Black family in Philadelphia, Duterte was an accomplished and sought after milliner. She married a local undertaker and learned the trade. When her husband died, she took over the mortuary, defying race and gender politics to become the very first female mortician in the U.S. She ran a successful business and was noted for being “prompt in her business affairs, and sympathizing and accommodating to all—rich or poor.”*

Historically, Black funeral homes were often the center of social and political movements, as they provided a safe haven for Black communities to gather, plan and organize. Duterte also utilized her funeral home as a catalyst for change, when she became an agent of the Underground Railroad. She would hide people in coffins or help disguise and integrate them into funeral processions to ensure their safe passage, as well as providing lodging to those in need. Duterte died in 1903, but according to the Register of Deaths in the City of Philadelphia, she is listed as having been the mortician who worked on a young man’s corpse, only two days prior to her own death.

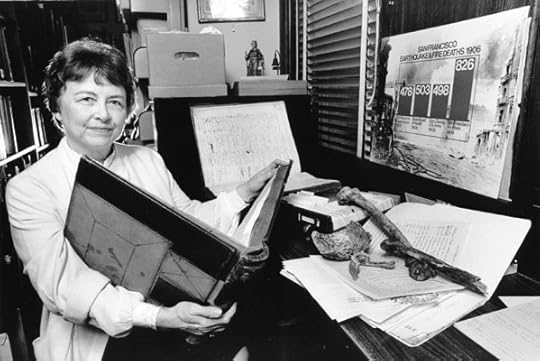

Gladys Hansen

On the morning of April 18th in 1906 80% of San Francisco was destroyed by a devastating earthquake and subsequent fires which broke out around the city, some lasting for days. The “official” death toll provided by the San Francisco Board of Supervisors was 478.

Enter librarian Gladys Hansen who, at the age of seventeen, was put in charge of the library’s California collection. Here, she began to research the identities of those who were killed or went missing during the disaster.

Hansen ran into a challenge many historians and genealogists face – racial bias in recording. People of color are often erased not only from history books, but official records. Among the “uncounted bodies of dead men and women…lying in morgues and under un-uplifted walls” (Los Angeles Times, April 18, 1906) were many people that were predominantly of Chinese ancestry. Their deaths, ignored and uncounted by city officials who plotted with investors, railroad tycoons and insurance companies to downplay and suppress the facts of the disaster so they could make a profit.

Hansen spent her lifetime uncovering this story and identifying the dead in an effort to bring closure to families and justice to San Francisco’s deceased. She has been dubbed “The Death Lady” or “The Death Librarian” for her work, bringing the actual death toll close to 6,000. Hansen died this year at the age of 91.

Resources

*“Undertaking.” The Christian Recorder 8 March 1862. African American Newspapers

Hughes, Alex. Phototextualities: Intersections of Photography and Narrative

Schechter, Harold. The Whole Death Catalog: A Lively Guide to the Bitter End

Christian, Kelly. Death Ladies, Dilettante Army

Axely, Catharine. VIDEO: Counting the Dead in the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake, The Atlantic

Sarah Chavez is the executive director of The Order of the Good Death, and co-founder of the feminist death site Death & the Maiden, a project that endeavors to explore the historical and cultural roles self-identified women have played in relation to death. She also has a blog, Nourishing Death, which examines the relationship between food and death in rituals, culture, religion and society. You can follow her on Twitter .

American Trailblazers and Mexican Revolutionaries – Great Women in Death History

June 16, 2017

June 13, 2017

Dazed: Why women are leading the death positive movement

TED: A burial practice that nourishes the planet

The New Yorker: Our Bodies, Ourselves

Caitlin Doughty's Blog

- Caitlin Doughty's profile

- 8411 followers