Caitlin Doughty's Blog, page 25

November 25, 2017

Skulls, Willows, Cherubs & Other Gravestone Emojis!

Your Guide to the World of Coco

Pixar’s new film Coco, tells the story of the Rivera family against the lavish backdrop of Dia de Muertos (Day of the Dead), a sacred and ancient annual tradition in which the souls of the deceased are able to return for a reunion with their living family members, in Mexico. Here, we’ll delve a little deeper into some of the traditional folklore and rituals that are depicted throughout the film.

As Coco opens, audiences are immediately introduced to several key elements of Dia de Muertos; candles, copal, and cempasuchil.

Candlelight is used to attract and guide the spirits of the dead during Dia de Muertos. In many regions a single white taper is lighted for each deceased family member. Tall candles are typically used for adults, while shorter ones are used for children.

In other areas, candles become a part of the altar itself, like the elaborate display seen here at a cemetery in Tzintzuntzan. Candles lit in the cemeteries are watched over throughout the night to ensure that no flame is ever extinguished.

A fragrant resin derived from a tree, copal is burned on altars and in cemeteries during Dia de Muertos to attract the dead. Copal was once used by Mexicas (the indigenous people of Mexico) to help carry prayers and messages to the Gods that resided in the land of the dead.

Orangey-gold flowers called cempasuchil, play an important role in Dia de Muertos rituals. It is believed that the spirits of the dead are attracted to the scent of this flower so, altars and graves are often decorated with them. Paths of their petals can be seen leading to a cemetery or into a house to help guide the dead, bridging the way between worlds of the living and the dead, as seen in the film.

The Mexica cultivated cempasuchil for use in rituals, ceremonies and also as a medicine. Water infused with cempasuchil was used to bathe corpses and is often planted on or near graves.

The story of the Rivera family is beautifully retold through panels on colorful tissue paper banners called papel picado. It is believed that Chinese paper cutting art came to Mexico via traders and merchants in the 17th century. Mexicans put their own spin on the art, trading in their scissors for chisels to bring familiar cultural motifs, like birds and skulls, to life.

In the early 20th century artisans in Puebla became renowned for their paper artistry and it was during this time papel picado became popularized. It is used not only during Dia de Muertos, but at various celebrations throughout the country.

One of the most endearing characters in Coco is Dante, the xolo dog. The Mexicas had an incredibly complex relationship with dogs, particularly when it came to death. For them, the xoloitzcuintli (xolo “sho-low” for short) were a beloved and sacred breed that acted as a guide and companion to the dead. It was believed that at the end of a four-year period of mourning after someone had died, the deceased’s family burned what remained of that person’s belongings as well as other offerings to Mictlantecuhtli, the Lord of the Underworld, upon their family member’s arrival in Mictlan, the land of the dead. The deceased would be carried across a river, the final leg of their journey, to Mictlan by a xolo.

People were often buried with dog statutes, or corpses were adorned with necklaces that had a dog figure on it. There are several ancient depictions of deceased persons arriving with their xolo to present offerings to Mictlantecuhtli. Artist Frida Kahlo, who also makes an appearance in the film, was frequently photographed with her xolos, and also incorporated them into some of her art.

Coco’s “spirit guides,” which act in a role similar to that of a xolo, are reminiscent of a type of folk art called alebrije. Like the character of Pepita, who is comprised of what seems to be a jaguar, an eagle and a lizard, alebrijes are fantastical, colorful creatures that feature elements of several beasts. If alebrijes look like something out of a fever dream it’s because they are. As the legend goes, in the 1930s Mexican artist Pedro Linares Lopez fell gravely ill and dreamed of these strange creatures who called themselves “alebrijes.” When Lopez recovered he recreated what he saw in paper mache form. Other artisans were inspired and began carving their own alebrijes out of copal wood.

Each year in Mexico City, just before Dia de Muertos, you can catch an incredible parade featuring life size alebrijes!

As seen in the Rivera family home, the ofrenda, a beautifully adorned altar in which photos and offerings comprised of gifts for the visiting spirits are placed, is the heart of Dia de Muertos. Drinks and favorite foods are laid out on the altar, along with things loved ones enjoyed during their lifetime. The ofrenda typically features the most iconic symbol of the festivities, the sugar skull.

In order to understand the significance of the sugar skull and how they came to be, you’ll need a bit of historical context. When Spanish Colonists arrived, they made great efforts to eradicate the indigenous people’s “pagan” practices of honoring their ancestors, under severe punishment and torture. In the 1700s the Spanish established laws controlling and abolishing Mexicans’ funerary and mourning practices. The laws issued included the following edict:

“The use of food and private banquets on burial days, during funerary commemorations or on the Days of the Dead is absolutely forbidden and reproved.”

The goal? “So that these abominations can be entirely uprooted.”

We know that Pre-hispanic people had been using a grain called amaranth not only as a main food source, but it was also used in sacred birth and death rituals. Amaranth sculptures of skulls and animals were believed to be offerings to the dead or perhaps to Mictlantecuhtli. The Spaniards outlawed amaranth, in an effort to physically, emotionally and spiritually weaken the people. The punishment for planting it was removal of one’s hands. Some anthropologists believe sugar skulls are tied to the original amaranth sculptures.

By the 1800s wealthy Mexicans were under pressure from the church to provide money, clothing & food to the poor when a family member died, instead of spending money on the funeral itself or a fancy funeral feast. Out of this arose a practice, that is similar to souling or giving out soul cakes on All Soul’s Night, to the poor in exchange for praying for the souls of their dead, which the church told them were trapped in purgatory. The sugar skull became a token of funerary charity when people would approach funeral processions and enact a form of ritual begging by asking for “Una calavera,” a skull. It later became a tradition to give calaveras in the form of sugar skulls to children and close friends and family. Sugar skulls are not only the result of oppression, but a testament to the resilience and spirit of Mexicans.

Cloths and baskets are often put out on or near the ofrenda, so that the ancestors have something to carry their gifts back to the land of the dead in. This is given a great modern twist in Coco, as we see the spirits passing through a customs area to declare their belongings.

It is here, at the customs area, that Coco first introduces the audience to the idea of the Three Deaths: “In our culture we die three deaths. The first death is when our bodies cease to function, when our eyes no longer hold a presence. The second death is when our bodies are returned to mother earth, and we can longer see it. The third death, the most definitive death, is when there is no one left alive to remember us.” – Via Victor Landa.

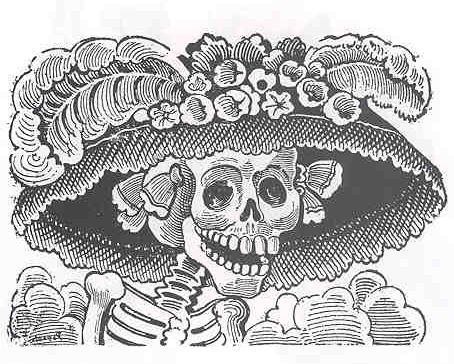

Once Miguel arrives in the land of the dead, he is literally given a hand by a woman that resembles another one of Mexico’s iconic symbols, La Catrina. Created by Mexican artist Jose Guadalupe Posada, who frequently used his art to comment on events and politics of the day. La Catrina was a satirical commentary on Mexican upper class women who favored and tried to emulate the culture, fashion and lifestyle of the Spanish (white Colonists), over their own.

Once Miguel arrives in the land of the dead, he is literally given a hand by a woman that resembles another one of Mexico’s iconic symbols, La Catrina. Created by Mexican artist Jose Guadalupe Posada, who frequently used his art to comment on events and politics of the day. La Catrina was a satirical commentary on Mexican upper class women who favored and tried to emulate the culture, fashion and lifestyle of the Spanish (white Colonists), over their own.

The streetcars that carry the dead in Coco, may pay homage to not only Posada’s famous work, but the many dedicated funeral streetcars of Mexico’s yesteryear, which once carried both copses and mourners to their final destination at the cemetery.

When Miguel gets off the streetcar, we see a fiesta in full swing! One important element we get a quick glimpse of is the release of monarch butterflies. In parts of Mexico monarch butterflies arrive every year during the time of Dia de Muertos. Many believe that the souls of the ancestors reside in monarchs and so, their arrival marks the return of the beloved dead.

Pre-hispanic cultures frequently utilized fire in ceremonies and festivals, and so it only makes sense that this ritual element would continue to be adapted in the more modern and spectacular use of fireworks. Fireworks are used in many different festivals, or as is the case in Coco, during celebratory events. Fireworks were also once used during funerals for young children, accompanying the soul of the child up to Heaven.

Music plays a huge role in Coco, and it does in Dia de Muertos too! There are many traditional songs for this time of year – some speak of death and mourning, while others, celebrate our folklore, like La Bruja (The Witch), and La Llorona, which is sung by the character of Mama Imedla during a pivotal scene in Coco. La Llorona, the archetypal weeping women who is lamenting the deaths of her children, is a figure deeply tied to Mexican cultural identity.

During Dia de Muertos, music is integrated into many regional celebrations – from town processionals, to interactive, historical reenactments.

Bands are often hired to play music for the visiting spirits, and sometimes you can find musicians roaming the cemeteries and hire them to play at the grave of your loved ones.

El Grito, is a type of musical cry or yell used to express emotion, and it is heard over and over again throughout Coco. Confused? (I promise, you know what a grito is, take a listen here). There are different types of gritos used in music, some are cries of pain for centuries of oppression, while others ring with joy and resolution.

The beautiful, hallmark song of Coco, is “Remember Me.” Although the focus here is on our connection to our ancestors, the makers of Coco were also honoring the importance of family, and calling attention to the many families who are separated by borders created by the living; and not just those separating us from the dead.

Remember me

Though I have to say goodbye

Remember me

Don’t let it make you cry

For even if I’m far away I hold you in my heart

Sarah Chavez is the executive director of The Order of the Good Death, and co-founder of the feminist death site Death & the Maiden, a project that endeavors to explore the historical and cultural roles self-identified women have played in relation to death. She also has a blog, Nourishing Death, which examines the relationship between food and death in rituals, culture, religion and society. You can follow her on Twitter .

November 17, 2017

Corpse Phallus Capers of Rasputin & Napoleon

November 13, 2017

CAN THEY KEEP ME FROM MY DEAD? (And More!)

November 8, 2017

Day of the Dead in the City of Angels

For the past several years when the veil thins each November during Dia de Muertos (Day of the Dead), I have traveled around Mexico, where my own ancestors are from. This year, however, I remained in the States and decided to observe how my home town of Los Angeles was marking this ancient and sacred ritual.

On the Eastside of LA, where I was born and raised, Dia de Muertos has been a part of community life here for decades, thanks to cultural and community arts centre, Self Help Graphics. They would be the first in the U.S. to move Dia de Muertos observances out of the home and into the community at large. Their annual Dia De Muertos events came to fruition during a time of cultural and political unrest in the Chicano community. Civil rights issues surrounding education, farm workers rights, police brutality, and war gave birth to the Chicano Movement, and Eastside LA was an epicenter of El Movimento.

It seems particularly fitting then, that the altars curated by Self Help Graphics and displayed throughout Grand Park in front of City Hall in 2017, carry on the legacy of El Movimento. Many of the issues our community struggles with today are the same ones our grandparents and parents fought to end, and are addressed here in the altars.

The altars are poignant, beautiful, heartbreaking, and infuriating. They tell the story of our ancestors, our community…and one day, when we join he realm of the ancestors, an altar may tell our story, too.

“This altar is lovingly dedicated to honor our Trans Family who have been murdered due to hate. Although they are no longer with us we remember their SPIRIT and know that their memories will always remain in our hearts We also honor those individuals murdered who have been misgendered or not reported at the time of their death.” – Latino Equality Alliance.

“Dedicated to Pachcucos, Zoot Suiters, and Barrio Warriors of yesteryear,” who utilized fashion and their unique style as a form of cultural and political resistance. By artist and historian, J.C. De Luna, The Barrio Dandy.

“This altar is dedicated to Eastside communities who, despite the adverse history of segregation, inequitable planning, and disinvestment from the public and private sectors that have plagued their communities; have grown strong roots of resilience and community activism as evidenced by the Chicano Moratoriaum and Student Walk Outs. Today, youth, residents, businesses and community organizations have come together and formed the Eastside LEADS Coalition, an initiative of the Boyle Heights Building Healthy Communities that is fighting displacement of residents in the Eastside of Los Angeles by working to create a community engagement process that will guide development that benefits existing residents and businesses, not development that displaces them. Our roots are deep and proud and we will preserve our communities through our collective work.” – Eastside LEADS.

“For our little angles, babies and children. Whether we met you in our arms or only in our hearts, you are forever in our minds.” – Celina Jacques.

“We dedicate this altar to our “teachers” – the ancestors who have endured trauma yet gifted our communities with legacies of resistance and resilience. We particularly want to acknowledge the radical women of color and gender non-conforming ancestors that have facilitated the transmission of survivance (survival + resilience), despite experiencing countless intersecting violences. We want to honor their stories, their knowledge, their practices, indeed, their very existences. We recognize that in order to achieve collective liberation, like the hummingbird, we must utilize our ability to fly forward while looking backward, to journey between the past and the future.” – Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies at CSULA.

“Despite the fact that LA County is experiencing the lowest crime rates since the 1950s, the County Board of Supervisors is moving ahead with $2.3 BILLION jail expansion plan – including a women’s jail in Mira Loma on land plagued by Valley Fever that’s more than a 150 mile round-trip from most families who will need to visit. Conservative estimates are that repayment on the bonds will escalate costs to $3.5 BILLION, with some financial experts claiming costs will reach $7 BILLION.”

“Once built, the plan will cost hundreds of millions more each year in operating expenses and untold human costs to the people detained, our families and communities. Instead, LA could invest in solutions that communities are pushing – efforts that are cheaper, more humane, more effective in building and maintaining public safety and result in lower recidivism rates than jails – including bail reform, drug treatment, mental health, job creation and community centers; solutions that humanize us and our communities, instead of policies that lock us up and/or fast track us to the cemetery.” – Unknown creator.

Sometimes, all we have to offer our ancestors is our love and gratitude, and a heartfelt reminder that we will never forget to honor them.

This year street vendors have been victims of violent, racist attacks. This altar is a reminder that working is not a crime. Street vendors provide a valuable service to the community and I know many people will agree with me when I say that one of the best moments of the day is when I hear the bell announcing the arrival of the elote man.

“They deserve our respect and appreciation. They are the perfect example of the resilience and creativity our people have in order to lead an honest life. Join us in celebrating those that have passed, but their legacy will live on forever.” – Leadership for Urban Renewal Network, and artist Astrid Anderson.

“This is dedicated to any and all POC/Queer/Gender Fluid folk that for reasons, such as: economical status, religious background, access to health care and public shame have felt that seeking help for mental health’s not an option. Stigmas regarding mental health in our communities make this a large issue that is hardly addressed, leading to suicide. We want you to know you are never alone. Please contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 if you are seeking help.” – Ni Santas, a WOC art collective.

“Dedicated to all of those whose dreams are threatened by our racist and corrupt government and to those that have passed away attempting to make their dreams come true.” – Guadalupe Homeless Project and Proyecto Pastoral at Dolores Mission.

“The Metro Blue Line connects Downtown Los Angeles to Long Beach with a 22 mile above ground track. This track is laid through many working class areas of South LA, and since its opening in 1990 over 120 motorists and pedestrians have been killed.”

“The above ground line has played a huge part in numerous suicides and accidents. On August 29th, 2017 Cesar Rodriguez, 23, was crushed to death at the Wardlow Blue Line Station after a police altercation over fare. His death further spotlights the discrimination and killing of black and brown folks by Police This altar is dedicated to him and all that have lost their lives on those tracks.” – Joan Zeta

A community altar to remember beloved pets.

“Reminiscent of Xochimilco and Mexico City, 9 floral vessels are set adrift on the water. They capture the essence and heart of Janitzio/Patzcuaro’s Day of the Dead celebrations of November 2nd. They also pay homage to the 9 levels that the dead face on their journey to Mictlan, as their soul transitions to the underworld upon their death. For generations waterways have served as a means of transport, transition, and influence between regions and people. Spiritually, they are regarded as a passageway for offerings to the gods and to the underworld, which has played a significant role in death and dying traditions in both Pre-European contact and post-contact eras.”

“Dedicated to loved ones past and the prospect of rebirth, the vessels are adorned with elements associated with the 4 directions (Suns). Among the offerings is the iconic image of the Catrina or “Lady of the Dead.” She rides atop a decorated floating vessel filled with marigolds and elements associated with the 4 directions. The Catrina is both the guiding vessel for the accompanying floral altars and the whimsical focal point of this tribute.” – Marcus Pollitz and LORE Productions.

Sarah Chavez is the executive director of The Order of the Good Death, and co-founder of the feminist death site Death & the Maiden, a project that endeavors to explore the historical and cultural roles self-identified women have played in relation to death. She also has a blog, Nourishing Death, which examines the relationship between food and death in rituals, culture, religion and society. You can follow her on Twitter .

November 5, 2017

ICONIC CORPSE: The Head of Jeremy Bentham

October 30, 2017

The Hungry Ghost Festival: When It’s Time to Feed Your Dead

One night a couple years ago, I was walking back to my apartment in the Jordan neighborhood of Hong Kong, when my path on the narrow sidewalk was almost completely blocked by a spread of food.

White styrofoam containers full of glazed, crispy skin chicken, fried noodles, dark green vegetables, and Chinese barbecued pork lay open on the sidewalk next to a tin of smoking incense. Nearby, a woman was busy standing over a large metal bowl, feeding colored paper into an orange flame.

The fresh, tidy “banquet” sat in contrast to the patina of ages old grime that shaded the concrete and tile buildings that populated my part of Kowloon, the peninsula that along with Hong Kong island makes up the city of my birth.

Looking further down the street, a street popular with superhero filmmakers to portray “gritty”, and “Asian”, the copious neon signs advertising restaurants, spas, and jewelry shops looked dreamy under the haze of more incense, and smoke leaping from fires in metal bowls and barrels. The smell of greasy food and burning paper filled my nose, a sweet, earthy smell that almost covered the scent of sweat, salt water, and garbage that perpetually perfumes Hong Kong.

Don’t get me wrong, “sweat, salt water, and garbage” may not sound like a treat for the senses, but something about the smell of Hong Kong soothes my soul.

However that night, mine was not the soul to be soothed. It was the Hungry Ghost Festival in Hong Kong, and the streets were alive with offerings to the dead.

Photo by Sam Tsang

The Hungry Ghost Festival or Yu Lan is the time of year when, in Taoist and Buddhist beliefs, the gates to the spirit world are opened and the deceased walk the earth again searching for their living relatives, potentially angry, and definitely hungry.

In places like Hong Kong, China, Taiwan, Thailand, Malaysia, and Japan, the seventh month of the lunar calendar is considered ghost month (a little different every year on the western calendar, this year ghost month was August 22 to September 19). The 15th day of ghost month culminates with the Hungry Ghost Festival. On this day it is vital to offer sustenance to your dead ancestors – or any other ghosts that might cross your path.

Otherwise they will haunt you, or even worse, curse you.

Haunt you or curse you. Though I definitely respect the seriousness with which many people – including some in my family – approach ghost month and the Hungry Ghost Festival, as a child growing up straddling old Hong Kong superstition and wanting my MTV, the threat of, “Ai-yah! You’d better be respectful, or your ancestors will haunt you and curse you with bad luck, “lah,” seemed to be the warning attached to every ritual, event, or holiday.

I think my mom even worked it into Christmas somehow.

It’s just fascinating to me that in cities like Hong Kong, that are known largely for their modernity and fast-paced business dealings, fear of retribution from ghosts and the dead still permeate the society. But I digress.

During ghost month, the ghost gates open at sunset, and the spirits are free to roam the realm of the living in order to seek out their relatives. The ghosts might be angry because they were not ready to die, they have unfinished business, or they are in Hell. One reason a spirit goes to the deepest pits of Hell is because their family mistreated them, forgot them, or didn’t properly bury or cremate their body.

One more thing to blame your ungrateful children for. “Thanks for sending me to Hell, you guys.”

Additionally roaming the earth as an angry disembodied spirit makes you HUNGRY.

HANGRY.

HANGRY GHOST FESTIVAL.

We were all thinking it.

Photo by Nathan Tsui

So in order to appease the spirits, the family must lay out food for the dead – usually outdoors, sometimes in the home. Not a few scraps, not a cookie or leftovers, we’re talking actual, fresh food. Some say you should provide the best you can afford.

Hence the mouthwatering banquets laid out on the street in my scrappy part of town. Even the homeless didn’t dare touch the food laid out for the ghosts. (I did see a cat steal some pork once – but cats are assholes and familiars of the dead so…)

For the entire ghost month, my street in west Kowloon was never without take-away boxes of food placed on the sidewalk after dark. Some laid out red cloth or flowers for the food to sit on, others placed bottles of water or beer alongside the offerings. It was all about giving people’s ancestors their favorite foods, or pleasing passing spirits so they wouldn’t bother the inhabitants of someone’s home or shop.

I’m not quite sure what happened to the food laid on the sidewalks after the ghosts had a taste. Since Hong Kongers are superstitious yet practical, I suspect the food ended up being consumed. I rarely saw leftovers sitting out in the morning (thought I often saw the remnants of a squashed meal that had been run over by a car).

Of course, not all ghosts can find their families. Sometimes, the dead return to the home where their family used to live, only to find a stranger living there. Woe be to the stranger who doesn’t acknowledge the dead!

If nothing else, whether you’re planning on hosting your returning ancestors or not, it’s recommended that you always have a light on in your home – as ghosts hide in the shadows – and always have at least a small offering of food out. An orange, perhaps a beer. Above all, the dead must not be forgotten.

Oh, and first rule of ghost month, don’t talk about ghost month. Specifically the ghosts of ghost month. Hauntings and curses abound.

There are actually a lot of rules to follow during ghost month and the Hungry Ghost Festival. Among them are:

1) Don’t begin a new job, get a new home, get married, be born, or do anything new during ghost month. Your new beginning may be doomed. If you have to be a special snowflake and be born during ghost month, only celebrate your birthday during the daylight hours.

2) Ghosts are drawn to red, so don’t wear red or else a ghost may attach itself to you.

3) Don’t pee on a tree. A ghost may be living in that tree.

4) Always close exterior doors, you don’t want to invite in wandering ghosts.

5) Don’t lean on walls – ghosts stick to walls.

6) Never disturb a ghost’s food and offerings. If you do, apologize profusely.

7) The night is not yours during ghost month, it’s for the dead. Unless it’s in honor of them, don’t do things outside after dark.

Along with food, the living also burn paper for the dead. At night, little charred bits of Hell banknotes would float through the air in my neighborhood.

Yes, the dead have their own currency, and it’s the job of the living to make sure the dead have enough money in the afterlife to maintain the life they were accustomed to. So Hell banknotes are purchased from shops devoted to selling paper goods for the dead – including but not limited to paper computers, cell phones, iPads, cars, and designer clothing – and burnt in order to make a deposit into the dead’s wallet. These days, the dead can have pretty much any luxury they want – as long as their family burns it.

On the night of the Hungry Ghost Festival, the link between the world of the living and the world of the dead is strongest. Families often hold banquets in their home, honoring the dead with empty chairs at the table, held for the guests of honor. The plates for the dead are heaped with their favorite food, their cups filled with their favorite drink.

Part of pleasing the dead is entertaining them, so public music and dance performances may take place in the street or parks. In Hong Kong, Chinese opera companies hold pop-up performances in public places to honor of the dead and the deities. Colorful, temporary shrines and temples appear throughout the city, so that people can stop to pray for the dead.

After the festival and ghost month concludes, if families have done right by their dead, they can go back to the spirit realm with a full belly, a happy heart, and a heavier ghost-wallet. Until next year.

I love ghost month in Hong Kong. I was lucky enough to be there for the tail end of it this year. And though the offerings after the 15th day of the lunar calendar had largely been reduced to incense and oranges, maybe some sweets, there was still an air of remembrance and ritual on the streets of my old neighborhood. Even as the area slowly gentrifies with the enormous cultural center being built on the harbor, the Ritz-Carlton’s tallest bar in the world only streets away from historic Shanghai Street, and posh European-looking apartment buildings dotting the neighborhood, the 2,000-year-old Hungry Ghost Festival endures.

Whether you believe in ghosts or not, the Hungry Ghost Festival is a time to think about the dead. More than the dead, one’s dead family. Since many in Asia believe that the spirit survives when the body fails, you might consider this just another way to care for your dead.

On one of the last nights of ghost month this year, I walked past a women in Jordan tending a fire in a squat, metal barrel. Taxis zipped past her, a loud group of people who were headed to the next bar jostled by, a nearby convenience store unloaded boxes from a truck. Life bustled around her, the city went about its business. But she just quietly, meditatively stoked the fire. From a distance, I watched her burn some paper offerings. They incinerated in a little puff of smoke that rose to the heavens.

And that is the beauty of the Hungry Ghost Festival. Under the glow of neon signs, Hong Kong is aggressive about moving forward, forward, forward, faster, faster, faster – chasing life. In a way, Hong Kong is aggressively alive.

But amidst that bright, unyielding life, there is some peace in knowing that lurking in the shadows, there is still room for the dead.

Louise Hung is an American writer living in Japan. You may remember her from xoJane’s Creepy Corner, Global Comment, or from one of her many articles on death, folklore, or cats floating around the Internet. Follow her on Twitter.

October 27, 2017

Salem Witch Trials – NEW Revelations

October 20, 2017

SO MANY WAYS TO DECAY!

October 16, 2017

GHOST MARRIAGE

Caitlin Doughty's Blog

- Caitlin Doughty's profile

- 8408 followers