Caitlin Doughty's Blog, page 27

August 16, 2017

Yes, I Write About Death: On the Ways People Respond to a “Death Job” and How I Handle It

He just kept blinking.

His brow was furrowed, his mouth was smiling though his eyes were not, his head was cocked. He chuckled uncomfortably and kept nodding his head – the universal gesture of,”Is that so? I have nothing to add…”

Poor guy, he looked like a Beagle trying to do math.

“Oh well, wow, so…you like that stuff?”

“I wouldn’t do it if I didn’t!” I chirped and sipped my wine.

The bride and groom swished by on their way to take a photo by a big tree.

“That’s some dress…huh?” He asked, eager to change the subject.

“It’s to die for,” I wanted to say.

Though I tend to get an array of responses when people ask me what I do for a living – from genuine enthusiasm to polite avoidance – I feared that I’d broken this fellow.

It had started with the most innocuous of wedding reception questions: “So what do you do?”

For most people it’s a simple question that breaks the proverbial ice and allows strangers to relate to you.

“You sell sweaters? I wear sweaters!”

But when you have a job that deals with aspects of American culture that Americans in general try to avoid or ignore, when someone asks that pesky question, you find yourself in a situation where the questioner has cornered themselves into talking about the unmentionable. (I don’t mean underpants.)

At a recent wedding, largely populated with complete strangers, I found myself answering this question over and over again. While a lot of people were really interested and wanted to talk more, I definitely brought a few conversations to a record-scratching halt.

Usually, when I’m surrounded by strangers, strangers who may or may not share my beliefs, I try to ease them in, test the waters.

“So what do you do?”

“I’m a writer.”

I’m always surprised by how many people leave it at that. But I’m so interesting! Ask me more! If someone told me they were a scientist, I’d definitely ask them what kind of scientist they were. Nonetheless, it’s an easy out for folks who are just being polite. Jerks.

Civilized humans carry on.

“Oh cool, what do you write about?” (Or some variation on this question.)

“I write about death.”

OK, that’s an oversimplification of what I write about and my body of work. If a person is into it, and asks me what I mean, I happily tell them about all the stuff I cover: death in folklore, pet hospice, “Morbid Minute”, death history, and so on. Really, most people can latch onto one of my bullet points and we can have a decent chat.

“Pet hospice? You can do that?”

“Why yes! Here are some websites to check out, new friend. I really like…”

Of course there are some folks who straight up balk.

“WHOA. That’s creepy.”

“Oh, OK. Death…um…It really was a lovely ceremony. You’re married right?”

“Oh God.”

Once or twice people have taken offense.

“What do you know about death? Do you think it’s ‘cool’? You’re so young. Do you really think you have a right to tell suffering people about dying?”

“I don’t have a right. But I’m not…”

When I sense that a person is heading down this path, I try to diffuse the situation with a disclaimer I’ve cobbled together over time.

I tell them that it’s never my goal to glamorize death or tell people how they should or shouldn’t feel about death. I only hope my writing gives people permission to broach the topic. More so, I’m not a mortician, I’m not a death professional, I’m an educated death journalist or memoirist, sharing my knowledge and experiences from a “civilian” perspective so that the conversation is a little less intimidating for other “non-death professionals” like me.

“…I’m not trying to instruct people on death, I’m just trying to make it OK to talk about it.”

Yes, it’s a little weird having a “disclaimer” in my cocktail conversation arsenal, but it does put some folks at ease and allows us to enjoy the cheese plate.

In the early years, I would try to sort of “talk around” the morbid side of my writing career. I’d talk about covering politics, vaguely about animal stuff, travel, “weird news”. I did this awkward song and dance to make people more comfortable; I didn’t want to be the gal who invited the Grim Reaper to the dinner table.

In the early years, I would try to sort of “talk around” the morbid side of my writing career. I’d talk about covering politics, vaguely about animal stuff, travel, “weird news”. I did this awkward song and dance to make people more comfortable; I didn’t want to be the gal who invited the Grim Reaper to the dinner table.

However, as my career became more focused, and I gained a little recognition for writing about death and deathly things, it became harder and harder to not talk about it.

“Yeah, I write about the whole spectrum of life –“

“– like geriatrics?”

“More like beyond geriatrics?”

I mean at this point in my life, it’s tricky to skirt what I do when I write for something called, Ask a Mortician.

“Oh…they’re lifestyle videos…”

But what I came to think about was, by trying to make my work “palatable” for people, was I tacitly apologizing for it?

Instead of “I’m protecting you from being uncomfortable” was I actually transmitting, “I’m sorry I write about death”?

And I wasn’t and I’m not.

If I was to “practice what I preach,” I couldn’t be apologetic or skittish. If my goal was to start a conversation, I had to make it safe to do so. Being at ease and confident in talking about death, it might give other people permission to be at ease and confident too.

So I cut it out.

Now, if someone asks me what I write about, I feel it’s my responsibility to tell people that I write about death as plainly as I might tell someone that I write about farm equipment. (There was a period of time that I kept getting pitches to cover “the year’s most innovative tractors”, so maybe that was a calling I narrowly missed?)

Of course unabashedly telling people what I do occasionally opens me up to scoldings or awkward situations – like my friend the blinking man. But I’ve come to accept that as part of my job. It’s OK for challenging conversations to start off, well, challenging (or clumsy, or sweaty, or defensive.) But hey, if we’re even talking about death, that’s a start – so I win!

Not that it’s a contest.

(It’s always a contest.)

I know that as death jobs go, mine is sort of the shallow end of the “YOU DO WHAT?” pool. Morticians, crematory workers, medical examiners, any person working directly in the death industry probably has their fair share of “awkward cocktail conversation” stories or encounters of outright contempt. In some ways I wonder if it’s even harder for aspiring death professionals, what with friends and family asking, “Why would you want to do THAT?”

If you work in the funeral industry, have a death-related job or profession, or aspire to be a death professional, what sort of response do you get from people when you “reveal” your job? Have you had positive experiences? Negative?

Has a man at a wedding ever stood blinking at you while he wages an internal battle between “good taste” and being polite to the death girl?

Whatever your experience may be, I’d like to think that for every blinking man there’s a would-be deathling, who sits up when one of us mentions what we do, and says, “Wait…we can talk about that?”

Louise Hung is an American writer living in Japan. You may remember her from xoJane’s Creepy Corner, Global Comment, or from one of her many articles on death, folklore, or cats floating around the Internet. Follow her on Twitter.

Yes, I Write About Death: On the Ways People Respond to a “Death Job” and How I Handle It

August 12, 2017

THE DEATH MASK EPISODE: History & Storytime

August 10, 2017

Vlogging the CADAVER TOMBS!

AMERICAN MUMMIES!

Dali’s Exhumation, Amputated Limbs, Celebrity Graves

August 9, 2017

SPAM and All the Bones in His Body: A Diary of a Death

It was an idyllic summer in small town Maine; warm and sunny, the chilled air rolling off the nearby harbor. Maine’s slogan of “The Way Life Should Be” seemed so true.

True, but also mocking me slightly, given the circumstances.

At the center of that pretty picture, Sam was dying. Sam was my father-in-law. After a year of battling cancer, he had retired from the fight. Sam chose to spend his remaining days at home in his 100-year-old farmhouse, with the woman he loved, the people he enjoyed, and the food he liked.

I told myself I was just going to Maine to hang out with Sam and my mother-in-law, Karen, but I knew there was more to it. I was going to say goodbye.

The following entries are adapted from my “journal” while in Maine – less a proper journal and more a few chicken-scratched lines I’d scribble in my notebook early in the morning, late at night, or when I’d go to my attic bedroom to stare at the ceiling and breathe deeply.

August 25

Got into town around 11pm. Karen came to pick me up at the airport. I felt terrible that she had to come get me so late. I never sleep, but I know they do.

We got to the house at a little after midnight. Karen and I sat at the table and drank tea. I kept telling her to go to bed, but she didn’t. We heard footsteps upstairs. “It sounds like Sam is up, he’s probably coming down to see you.” I heard the whir of the chair elevator coming down the stairs.

Sam appeared in the kitchen doorway and told myself to BE NORMAL. Sam was so thin. I’ll never get used to seeing him with a walker.

I should be used to it. Every time I’ve seen him in the past year he looks thinner and grayer in the face. But this time it made my chest ache.

“One of the childrens is here!” he grumbled and smiled. Such a relief to hear Sam’s voice in that body. I hugged him as tight as I dared. He was all bones. I’ll never forget how that hug felt.

I made some joke about Sam’s fancy pajamas. He laughed and told me I was a pain in the ass.

Sam didn’t sit, he stood in the kitchen doorway with his walker. He talked in circles a little, because of the meds, Karen said later. It was distressing to hear him speak in non sequiturs.

Somehow he got to joking about his muscles. “Talk about a six pack? I got a sixteen pack!” He was talking about being able to see all the bones in his body.

I laughed at his joke, but my I wanted to cry a little, too.

August 26

Jet lag hits me so hard in Maine.

Got down to the kitchen around 10:30. Felt like I was in soup. Karen was working at the table. Sam was still in bed.

I made coffee and eggs and I made Karen eggs, too. She likes hers over easy.

Heard Sam coming. Why was I nervous?

I feel like a crap person for being startled at his thinness again.

__________

Sam and I sat around the kitchen table gabbing about my move to Japan. Sam talked about coming to see my and my husband in Yokohama. I allowed myself to talk with him about the things he wants to do there — food, gardens, geisha. The whole thing had the same sensation as a lie. I felt like a crap person again.

He said, “Though I don’t know if I’ll actually get there, but I’d really like to get there.”

I can’t be a weepy mess. HE WOULD HATE THAT.

__________

Sam hates it when I try to help him. So I don’t. It feels like a dick move to not help him as he cooks oatmeal, but how can I treat him like an invalid when he still roars at me?

I did something dumb, and he snatched the spoon away. “Over my dead body,” he said. And we laughed for real.

He told me I was a pain in the ass again. I told him “takes one to know one.”

__________

I gave Sam the multitude of weird SPAMs I brought him from Hawaii. Eight cans. He was so happy! I love hearing him make plans about food. He has his tasting powers back [while Sam was in and out of the hospital, undergoing radiation, he was on a medication that made it hard for him to taste much of anything besides sweets] so food is a pleasure again.

He was really excited about the Hickory Smoke SPAM and the spicy SPAM.

__________

We are watching The Food Network, and Sam starts to doze. I watch him breathe.

August 27

I went downstairs at around 10, and Sam is already up at the dining room table on his computer. Karen was in the living room curled up on the couch staring at the TV.

The house felt tired.

I started to make my breakfast and Sam came into the kitchen.

“Did you know you can order SPAM on Amazon?” he asked.

“I didn’t, but that makes sense.”

“I ordered seven cases of SPAM!”

“What are you going to do with all that SPAM?”

“I think the bigger question is, what is Karen going to do with all that SPAM! I mean, I plan to eat a good portion of it, but both you and I know that I’m not going to be here to eat all that SPAM.”

Damnit. I laughed, was delighted by the weirdness of it all, felt nauseous, and afraid all at once. It must have been on my face.

He called me sweetie or sweetheart. I don’t hate it when Sam calls me that.

He told me he was so happy I was there. He told me that Jeff was a really good kid, he didn’t know how good of a kid he was until all this happened. [My husband, “Jeff”, was 35 at the time – I didn’t, and don’t have, a child-husband.]

“You’re a good kid too, you know. You eat me out of house and home, but I think we’ll keep you.”

He talked about feeling good these days, but knowing that he looked “like this.”

He talked about making plans for travel and adventures – how much fun he had in Hawaii with Jeff and me two Thanksgivings ago. But then he rounded out his thoughts with something like, “if I don’t keep planning, then that’s it. Goodbye.”

The temperature in the room changed suddenly. I needed something to do so I picked up Sam’s mug and asked him what kind of tea he wanted. It was like a thunderclap of anger in the room.

“If I want tea, I’ll get it myself, now PUT THAT DOWN.” I put the mug down on the kitchen table. I felt guilty.

“You just can’t take a hint, can you?” He was joking a little bit, but there was an edge in his words. “I can get my own tea.”

We’re so quick to try and steal life from those who are holding on tight to it. Life isn’t just the big adventures, it’s also the normalcy of making your own tea.

__________

Sam had SPAM on toast for dinner. He cooked it himself. Karen and I told him it looked like cat food and kind of smelled like it too.

“And you think you smell like roses?” he said to me.

__________

I cleaned the kitchen after dinner. I think it really annoys Sam, but Karen likes it.

The house is different at night. After nine o’clock it’s like death and sickness gets to take over for a little while. Everyone’s tense.

The lights never go off upstairs. Sam watches TV all night long, dozing for an hour or so at a time. Karen can’t sleep so she plays on her iPad.

From behind my bedroom door I hear talking and footsteps all night long. Light comes through the gaps between the door and the frame, slicing through the dark.

August 28

I dragged my ass out of bed at 10am and took a shower.

Sam was watching TV when I came downstairs. “Well look who finally decided to grace us with her presence.” It felt so normal to see him in his chair, calling me lazy. For a moment it was like a few years ago when vacations in Maine felt carefree.

I’m so f**king tired of mourning what was, and feeling like I’m pre-mourning what will be. It feels like a betrayal to Sam.

As I made breakfast, Karen worked on her computer. She asked if I wanted to play cards with Violet [her best friend] and her that night. “We’’ll have drinks in the parlor and play cards in here.” She seemed cheery over the prospect.

I was so glad she suggested it. it’s something a little out of the ordinary to look forward to.

I see Sam’s state reflected in Karen and I can’t even begin to imagine how she feels.

__________

One of the hospice workers came to the house. When I answered the door, she gave me a hard look, like I might be a burglar. Luckily Karen swooped in and introduced us. Then she was all sweetness and spunk. Like Kathy Najimy in Sister Act.

She asked Karen if she needed any sweeping or ironing done. Karen said no. She went upstairs to work with Sam. I could hear Sam laughing with her. She brought ease with her.

What a difficult job. She was like a walking, talking sun shining light into the gloom.

I hadn’t realized that a patina of gloom had settled over the house, until “Kathy Najimy” came in.

___________

Watched more Food Network with Sam. The late afternoons are the most unpredictable.

We were having the most average conversation about how to properly cook scallops, when the switch flipped.

When this happens there’s something frantic about him. It’s like the tape on his life gets fast forwarded, and he’s trying to slow it down.

He coughed hard and I asked if he was OK. “I’m OK, are you OK?” there was a whiff of a challenge in there.

“I’m good.”

“Lucky you.”

__________

Dinner was stressful. The family came over. We ordered Thai food. Food was spilled. Feathers ruffled. I felt like I was in the way.

I gave the kitchen floor a good scrub. Sam told me to knock it off when I started to attack the baseboards.

I know I shouldn’t do it. My attempt to be helpful is just a reminder that things aren’t what they once were. I’m like a little angel of death flitting around the house with a mop.

But I can’t stop. I really should. I will.

Violet didn’t come over and the card game didn’t happen. Karen and I just sat in the dark kitchen and drank wine and talked. She seems lonely.

August 29

I threw myself out of bed early – 8am! – to have breakfast before going to the airport around 11am.

Sam was already at the kitchen table. He was eating SPAM on toast. He seemed chatty and in high spirits. I thought he was angry with me, he didn’t seem like it today. He seemed downright chipper.

It was cruel how normal the morning felt. I was mad that now, whenever good things happen with Sam, I think about how unfair everything is. I’ve never characterized death or dying as truly “unfair” until I’ve been so happy in the face of it. Damnit.

Karen came in and out of the kitchen asking for eggs and messing with her new cell phone. I think I set it up for her. Or I totally destroyed it. One of the two. Time will tell.

I started to do the dishes after breakfast and Sam barked, “Drop it! Sit down, and shut up.” I literally dropped the pan in the sink with a clank. “Atta girl,” he said. I sat down at the table.

Sam asked why I had to go so soon, that I just got there. It wasn’t his mind playing tricks on him, he always says this.

When I joked offhandedly that I’d finally be out of his hair, he cut me off. “Don’t you ever think, for one second, that I don’t want you here. I always want you here.”

I couldn’t answer properly, I just said “Thank you.” Then we talked about French food and how amazing the food was in Paris. He told me I should go. I said I’d work on it.

I felt terrible, as usual.

I hugged Sam, and for the hundredth time in just a few days I felt a surge of rage at how thin he was. His spine poked up through his thin t-shirt and met my hands.

It was all so unfair in that moment. Death was stealing Sam from us piece by piece, pound by pound, thought by thought. It’s brutal. Greedy.

To have to watch your loved ones watch you die. To see fear and worry – the same fears and worries you are living with – written on their faces, and then feel obligated to put them at ease. Because that’s what Sam did. He didn’t have time to fret too much about his own death, he was worrying about what it would do to us.

“I’ll miss you, kiddo. Come back soon.”

__________

Sam died two months later. There’s a lot of SPAM in Karen’s pantry.

(All names have been changed to respect the family’s privacy.)

Louise Hung is an American writer living in Japan. You may remember her from xoJane’s Creepy Corner, Global Comment, or from one of her many articles on death, folklore, or cats floating around the Internet. Follow her on Twitter.

August 3, 2017

Rhinestones, Madness, and Resurrected Corpses: The Love Story of Tony & Susan Alamo

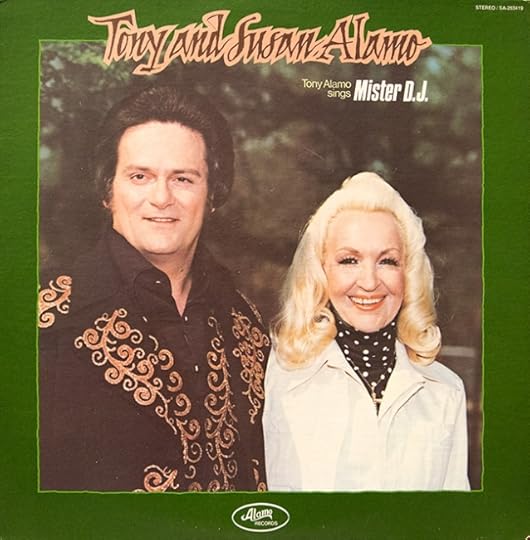

If I had been born about 20 years earlier and one hour south of here, I may have appeared in this story. The story of a bad boy who wants to be Elvis, a girl with a bleached blonde bouffant, a stolen corpse, the mind-altering power of Jesus Christ, –all encrusted in rhinestones. This is the story of Tony and Susan Alamo.

Tony Alamo was born Bernie Lazar Hoffman in 1934, in Joplin, MO. He claimed his father, a Jewish immigrant from Romania, had been a dance instructor for Rudolph Valentino. As a teenager, he left Missouri for Los Angeles, CA to find fame in the music industry. He recorded a single “Little Yankee Girl” that’s weird as hell, but mostly he just talked the big talk. He would tell everyone who would listen that he was a hotshot music promoter who’d worked with The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, and Sonny and Cher. That’s how he met Susan.

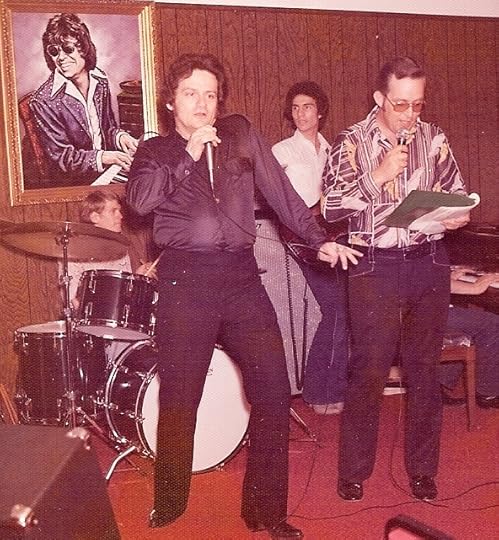

From Tony Alamo News, Tony singing at his restaurant banquet hall. Dyer, AR.

Susan was born Edith Opal Horn, also of Jewish descent, in Alma, Arkansas. She had moved to Hollywood to become an actress, but was supporting herself in the meantime scamming churches. “Put your dress on,” she would tell her daughter Christhianon Coie, “we’re gonna go do a church.” According to an interview Christianon did for the Southern Poverty Law Center in 2008, she was present when her mother met her match. “I’m watching them and it’s like a tennis match of horse crap. They both think the other’s got money.” It was at this meeting where Susan launched the greatest pickup line of all time. “Tony, I’ve got to ask you a question. Did you know that Jesus Christ is coming back to Earth again?” Tony looked deep into her eyes and says “Why, yes, Susan, I do. But how did you know?” And she said, “Well, let’s go up to my apartment and talk about it.”

The two were married in 1966, three times in a period of two days. According to a 1980 court deposition, Susan stated that the couple was first married in Mexico. She worried that the Mexican marriage wasn’t good and legal and refused to sleep with Tony. Later that day, frustrated, Tony supposedly bought not one, but TWO marriage licenses in Las Vegas, and they were married another couple of times to make sure it stuck.

If marrying Susan wasn’t serendipitous enough, within the same year Jesus came to Tony and told him that it was his job to tell the masses of the second coming of Christ. So, the newlyweds built Music Square Church in Hollywood and began bringing the prostitutes, drug addicts, and hippies of California into their fold.

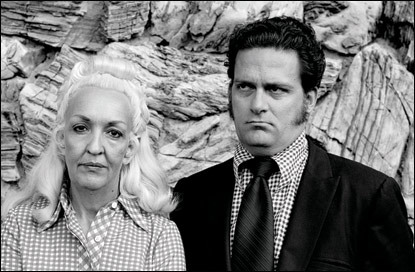

From SPLC, Tony and Susan Alamo.

The Alamo ministry preached a range of ideas; end times paranoia, UFOs as divine messengers, and Vatican conspiracy theories. Tony hated the Catholic Church and blamed them for everything bad that had ever happened– including Nazism. One Alamo tract entitled “The Pope’s Secrets” read “The Vatican is posing as Snow White, but the Bible says that she is a prostitute.”

From SPLC. Susan in front of the California compound.

Followers flocked to worship with the Alamos, and the church grew into it’s own compound in Saugus, California. Members of Music Square Church would live communally at the compound and work at Alamo-owned businesses. On payday, they’d return their paycheck to Tony, who would then give it to Jesus. Tony and Susan were on top of the world. They were in love, rich, famous and the rulers of their own empire.

In 1975, Susan was diagnosed with cancer. This wasn’t completely devastating because the couple TRULY believed themselves to be immortal. “I am the Lamb of God,” Susan would say on their television program.

As a child, Susan had suffered from tuberculosis and was near death, but was visited by angels at her bedside in Arkansas and suddenly HEALED! When Susan shared the story of the healing power of Arkansas with Tony, they packed up their furs, turtle leather platform boots, Bibles, diamond pinky rings, and crew of Jesus freaks in a fleet of black Cadillacs and headed to Dyer, Arkansas, population 486.

In Dyer, the Alamos moved into Susan’s childhood home and began remodeling it with materials shipped in from Hollywood. The couple was fond of red carpeting, chandeliers, and velvet wall coverings and installed them in every space they occupied.

At this time, they also began construction on a sprawling Victorian home on the mountain, complete with dormitories for their followers and a heart shaped pool for Susan. A grand church hall was constructed for their evangelical TV show where Tony regularly sang love songs for Susan, such as my personal favorite “I Love You So Much It Hurts Me.” Then they set to expanding their empire in the neighboring town, Alma. Once it was all said and done, the Alamos owned 30 businesses in a town of 30,000, including a supermarket, western store, restaurant, a candy factory, and hog farm. In President Bill Clinton’s autobiography My Life, he talks of a trip he made to the Alamo restaurant to see Dolly Parton perform and describes Tony Alamo as “Roy Orbison on speed”.

In 1982, despite Tony’s orders for intense prayer, Susan’s cancer worsened. She died on April 8th at a local hospital. Tony was devastated and blamed his church members for not praying hard enough. But luckily, they had immortality on their side. She would rise from the dead. He was sure of it.

Instead of burying Susan, Tony brought her embalmed body (dressed in her wedding gown) back to their dining room and ordered his followers to stand around her 24 hours a day, praying for resurrection. A local florist, Shirley Lovett, was hired to deliver flowers to Susan almost daily.

In a 2008 interview for The Oregonian, Elishah Franckiewicz remembers Susan’s death. “I believed 100% that she was going to rise from the dead.” Tony talked publicly about the resurrection and local radio stations made fun of him by playing “Wake Up, Little Susie” over and over. She said that week after week, they would be forced to lay down and curl up with the rotting corpse. “She smelled. She was cold and really, really hard. She was dead.” Every day that Susan remained dead, the children were beaten.

Finally after 6 months of no luck, an exhausted crew of cult members finally placed Susan in a newly constructed mausoleum on the grounds. Franckiewicz was devastated and remembers laying on the mausoleum still praying for Grandma Susie to rise.

From SPLC. Tony and Mr. T in Alamo jackets.

Stricken with grief, Tony Alamo did what any heartbroken evangelist would do. He created his own fashion brand. He was gonna dress the stars! High on coffee, vitamins, and Jesus– Tony’s cult members and their small children would work until the wee hours of the morning bedazzling jackets with elaborate cityscapes of rhinestones and Swarovski crystals. These jackets would sell for anywhere from $600 to $5,000 and graced the backs of celebrities like Dolly Parton, Mr. T., Hulk Hogan, and, Sonny Bono. Alamo soon set up shop in Nashville, TN where he could keep close proximity to the stars of the Grand Ole Opry.

With the love of his life temporarily interred, Tony also remarried, multiple times. First he tried his hand with a couple of 15 year-old girls. When that didn’t pan out, he married Birgitta Gyllenhammar. Two years later, she left him, claiming that he tried to force her into getting plastic surgery to look like Susan. You can call it what you will, but I call it romance.

Up to this point, Tony had charmed his way out of various legal troubles. In 1991, the law finally closed in on the Alamo Foundation and charged him with tax evasion. Prior to the inevitable raid, Alamo ordered cult members to gut the mansion. They ripped out carpeting, light fixtures, furnishings and Susan, from her marble tomb.

nwaonline.com

One can only speculate on Susan’s post-death adventures, but in 1998, after 7 years of being on the lamb with Tony, her body showed up on the stoop of a Van Buren, Arkansas funeral home. “The casket was covered with hay,” Lovett the florist told a local reporter. “When he disappeared, he took her with him for a spell, but I think he knew if he was ever found, they would find her body. I think that’s why he put her in a barn somewhere.” Susan was eventually interred in a crypt in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

In the years following Susan’s death, Tony was in and out of prison. Tax evasion, child abuse, and threatening to kidnap a federal judge were just a few of the allegations against him. However, by 1998 he was free, and began taking on multiple wives, all of them between the ages of 8 and 15. Susan had been dead for years now. She may have been re-born and he was on the hunt for her. They would be re-united at last! Needless to say, the world was horrified.

On September 20, 2008, Tony was arrested for trafficking young girls across state lines and forcing them to marry him. He was found guilty on ten counts and sentenced to 175 years in prison. The trial was just a few blocks from my house. My friend Harriet Wells, who has fueled my Alamo fascination, attended the trial. “He looked like a vampire. White skin, dark sunglasses, and jet black hair.”

On September 20, 2008, Tony was arrested for trafficking young girls across state lines and forcing them to marry him. He was found guilty on ten counts and sentenced to 175 years in prison. The trial was just a few blocks from my house. My friend Harriet Wells, who has fueled my Alamo fascination, attended the trial. “He looked like a vampire. White skin, dark sunglasses, and jet black hair.”

On May 2, 2017, Tony Alamo died in a North Carolina prison. He was 82. Sadly, I was right in the middle of a rhinestone coated jacket negotiation when I got the call.

Since 1991, the majestic 13,064 square-foot Alamo compound on the mountain in Dyer, Arkansas has set empty, slowly decaying. The property was purchased in 2000 by a couple of entrepreneurs who have turned the majority of the grounds into an outdoor wedding venue.

This April, the local paper printed a story, complete with photos, saying the new owners were ready to turn the compound over to a “legitimate Christian charity” for restoration as a ministry. I decided to email the property owners and ask for a tour. I told them I was writing a story about the Alamos and would love to walk around and get a feel for the place and possibly a quick interview. Mrs. M., as I’ll call her, asked where the article would be posted and I nervously replied “www.orderofthegooddeath.com.” After reviewing this good-looking website, she decided she’d gladly let me tour the estate for $1000 and even let me stay in a “premium bed” in the wedding chapel next door. She closed the email by asking for my credit card information.

The next day, Harriet and I were sitting in our little vintage shop as a husband and wife were perusing our “Wall of Alamo.” (As I said, we are nothing if not Alamo historial enthusiasts.) They were looking at the record sleeve for Tony’s album “Love Songs for Sue & You” and the woman says to her husband “Is that the chandelier that hangs over Mom and Dad’s dining table?” I tell her that it’s Tony and Susan Alamo’s home and she says “Yeah, I know, my folks bought their old house.” SERENDIPITY. “I always try to get Mom to dress up as Susan Alamo for Halloween and answer the door for trick or treaters.” We converse for a while about the house and they eventually leave with my phone number. “My dad loves to talk.” She tells me.

I wait for weeks for the call. Nothing happens. I beat myself up for not getting their number or names, even. Finally, I have to act. I call the Crawford County Genealogical Society. The man who answers the phone may be the oldest person alive. I tell him that I met some people who know some people who bought Susan Alamo’s childhood home and that I’ve lost their contact information. He says as slowly as physically possible “Well, let me see if I’m smart enough to do this.” I can literally hear him flipping through a Rolodex. Then he starts reading off phone numbers. “Here’s his work number. This here’s his cell phone. And this is the home number.” “What’s his name, again?” I ask. “Well, it’s Billy Gale Morse! Our mayor. If he doesn’t help you, just give me a call back.” I couldn’t believe my luck. I love small towns.

I called Mr. Morse and told him about my article. He immediately started telling stories faster than I could write them down. He finally stopped and said “ Just come on down and let’s have a visit. You can see the house for yourself.”

A week later, Harriet and I loaded up and drove an hour south to meet the mayor. We arrived sooner than expected so we decided to just drive by the mansion and have a peek. We were greeted with a No Trespassing sign at the bottom of a scary and steep driveway. As tempted as we were, we turned around.

Original Alamo home.

We arrived at the Dyer City Hall, which was closed and looked like it may have been closed for the last 20 years. Billy had forgotten about our meeting, but could be at his house, which was just down the street, in ten minutes. “Stay cool and don’t knock on the door. My wife doesn’t know you’re coming.”

Ten minutes later, we’re inside. Every square inch is wallpapered. Our feet, at last, are sunk into plush, blood red carpeting. Before we begin, he introduces us to his wife. “She likes to think of herself as an invalid, but she’s not.” He whispers. “Jo Ann, there’s some ladies here from Fayetteville who want to talk about the Alamos.” She was horizontal in a Lazy Boy, with her hair and face done up like Tammy Faye Bakker. “I’m sick!” she said and waved us away.

We went into the dining room. A chandelier hung above our heads as he began to tell us all he could remember about the Alamos. Most things he said never made it into my notebook because they were so jumbled together. Timelines were skewed, fact bled into speculation, and on top of that, it was just so dang hot in that house.

The bedroom where Susan was visited by angels.

He tells us of some brothers who were members of the Alamo cult for years and then were ousted when Alamo borrowed a $10,000 start up fund from the brothers’ folks and refused to pay it back. According to the story, Tony wanted to bring the wives of the brothers back into the fold, so he pronounced the couples divorced and took the wives back to remarry other members. This brought trouble for Tony when the brothers involved an attorney who specialized in cult cases to file a two million dollar Alienation of Affection lawsuit against him. They won.

Billy told us stories of elections the Alamo’s controlled, of Elvis Presley visiting the Alamos for clothing orders, and ceiling murals of pheasants his interior decorator forced him to paint over.

Finally, he put the icing on the cake with this one. After Susan’s death, Billy and Jo Ann owned a large house on a hillside in Dyer that they were trying to sell for $350,000. One day the real estate agent called and said “Tony Alamo is here and he’s interested in your house.” So Billy went to meet the agent and Tony at the property. “Tony walks up with a couple of his thugs on either side of him and about fifteen feet behind him is his new bride. She couldn’t have been over fifteen and she had a couple of thugs of her own.” Tony liked the house and told Billy “Here’s what I’ll do. I will trade you the property for an artesian well in the city of Los Angeles that holds enough water for the entire city– FOREVER.” Billy refused.

Lobby of the Alamo Church in Dyer.

When Mr. Morse was obviously exhausted, he sent us to our next stop, the church directly across the street. It had been built in the late 70’s as the official Alamo Ministry church. It was also the home of the weekly television program. The church had been stripped of furnishings and flooded when the government raided the Alamos in 1991, but what remained was a 50’ mural painted by a member of the cult. It was truly majestic. The mural can be seen in the background of the Alamo Christian Ministries videos from that time.

Church mural painted by cult member.

As we were leaving town, we decided to risk driving by the mansion. The mayor had egged us on and we couldn’t imagine being this close without seeing it. We crested the hill where the mansion supposedly sat and it was nowhere to be seen. We drove in circles and then for some reason, went off-roading down a grassy hill. “Just keep your head up and act like we know what we’re doing.” I told Harriet. We had no idea what we were doing.

Sign in the middle of a field near Alamo mansion.

Finally, as we were feeling defeated, there it was. I jumped out of the car and ran past the Trespassers Will Be Prosecuted sign to the heart-shaped pool I had been dreaming of. It was even more beautiful than I imagined.

As I was walked back, I happened to notice an open door on the lower level. If the Alamos taught me anything, it’s that when the Lord opens a door, you go through it.

The open door on the lower level.

It was damp and really dark. Ahead of me was the most beautiful staircase I’d ever seen but I just couldn’t make myself go up into the pitch-black darkness ahead.

I went outside and climbed the outer staircase. A previous trespasser had busted out a back window. I did what I felt compelled to do and stepped over the glass into the bright kitchen, where Susan’s body had allegedly been displayed for six months. There was a puddle of green slime in the middle of the floor. Quickly, I made my way through the house. An abandoned baby doll, a hide-a-bed, a tiny swatch of velvet wallpaper, and a pile of moldy bibles were all that was left behind. I grabbed a handful of bibles and shoved them out a window to Harriet. “Bibles! Take them to the car!”

Kitchen/dining area where Susan’s body was supposedly displayed for six months.

Front room.

Abandoned hide-a-bed.

Last bit of velvet wallpaper.

As soon as she got the sacred books safely in the floorboard, a car approached. It was Mrs. M., of “$1,000k to tour the property we had just broken into” fame.

Standing outside of the mansion, on the hottest day of July, Harriet was suddenly filled with the spirit of the Alamos and spilled forth the most beautiful stream of lies. “We’re just so lost. I’m with my friend, Sheila, and we’re looking for some wedding chapel. My granddaughter is getting married in October. Oh, it’s over there? What even IS this place? The Alamo Compound? Never heard of it.” She looks at us skeptically. “Y’all just hold on tight right here. I’ve gotta run to the office and I’ll be right back. I’ll take you down to the chapel.” By this time, I’ve slithered my way back up to the van. We jump in, crank the AC, and drive as fast as we can back to civilization.

Greta P. Allendorf lives in Fayetteville, Arkansas with her daughter, Maude. She is a home funeral guide and serves on the board of the National Home Funeral Alliance. In her spare time, she sells dead people’s clothing at her vintage store, Cheap Thrills, and obsesses over cults.

Rhinestones, Madness, and Resurrected Corpses: The Love Story of Tony & Susan Alamo

July 18, 2017

Faces of Death: Kelly Christian

Tell us about your work, Kelly.

I am a writer and artist. I am interested in so many components surrounding death, but many of them come together under the umbrella of social history. I am deeply interested in how we, as human beings, respond to death and loss in large scale ways. Cultural responses to death fascinate me. A large part of my current writing and research explores how death was imagined and managed in the 19th century United States, an era where shifts in medicine, capitalism, and religious practices (among many other spheres) allowed for death to be revered as both a spiritual milestone, social experience, and natural component of life. I am fascinated by this, especially because contemporary mourning culture is practically non-existent. I strive to create space for a more comprehensive and cohesive dialogue surrounding loss, mourning, and death in our current landscape. I use writing as a tool to bring historical moments and events into conversation with modern theories on how and why we make sense of things in the way we do when it comes to death.

I am also interested in highlighting the ways that power is always at play, even in our darkest moments. At my most ideal, I imagine that creating thoughtful work around death and having conversations about it allows us to build bridges to people who we may not otherwise build relationships with. If we consider the many political divides that disrupt families and communities, perhaps a dialogue about the one thing that we all experience would bring us together. I want to have conversations about what it feels like to mourn and what it feels like to prepare for your own death with people I may otherwise not be able to connect with.

After experiencing a sudden loss at the age of 17, I felt extremely isolated while trying to make sense of what had happened. In the following years, I became extremely interested in how I could find ways to ensure that other folks felt more supported while grieving. This has come out in many ways. As an avid anti-war protestor in the early 2000s, I started photographing military funerals for fallen soldiers to document a national loss that was both illegal and going unnoticed. Despite my own feelings on the war itself, I was able to create meaningful relationships with the families of those burying their sons and daughters. They let me into their lives at their darkest moment, and it completely changed how I wanted to go about getting to know folks who have different experiences than I do. We all mourned the same.

Beyond this, I completed my work in graduate school about mourning photography and its unnoticed importance. This has led me to writing, photography, and new media projects in the last several years, which has been extremely fulfilling and has shaped how I approach my day to day life as well.

What are you working on his year?

I continue to write a bi-monthly article for an online publication, Dilettante Army. I love writing for them because they allow me to dive into anything that I’m feeling an itch for. My editor, Sara Clugage, is always supportive of my more macabre projects. I feel very lucky to write for them. I am currently working on some longer form work on the social history of bodily preservation, both human and animal. I’ve started some preliminary research and writing, but look forward to carving out some more time and energy for it. That writing ties together some of my photography that I’m currently working on. I am documenting forgotten or unsupported taxidermy dioramas that are no longer being kept up in museums. There are many museums, many are smaller institutions – that don’t know how to support the preserved animals, have new buildings that they couldn’t be moved to, or have replaced old dioramas with newer exhibits. I hope to highlight how taxidermy can be an entry point in how we think about death, because it is familiar and accessible to many.

What does death positivity mean to you?

Death positivity means creating and maintaining dynamic and honest dialogues surrounding death, mourning, and loss in contemporary culture. Being open and finding a sense of positivity and growth in our conversations and work surrounding death is crucial for building empathy and understanding. It can be very isolating to encounter the death of a loved one or in thinking about ones own death, and my hope is that by making work around death will allow people to interact in a more open and supportive ways. I think that some of the anxiety we come up against in doing death positive work could be alleviated if there was simply more room to make sense of death openly with folks in and outside of our communities.

What other death-related job that you don’t have, would you want?

I would love to be a forensic anthropologist. I am so intrigued by how our bodies can share information about us, even after we die. As someone who is driven by research and problem solving, forensic anthropology would certainly be an enticing career choice. I do daydream of going back to school and seeing if I could tackle the science requirements. In the mean time, I’ll just have to read about the amazing work of actual forensic anthropologists.

When you die, what do you want done with your corpse?

I want a very low-key green burial. I prefer that my body just go back into the earth. It would be great to have my body become part of the rest of the world; parts of trees, the air, fresh soil, sustenance for life. I don’t want to take up room or resources; I’m not overly fond of embalming for this reason, although I do understand its appeal. I would hope that in lieu of a traditional funeral, there would be an epic party for all of my friends and family to share stories and spend time together.

Kelly has written some wonderful pieces on death and photography for The Order, like A Shocking Likeness: Photography and Death in the Civil War, and The Unpleasant Duty: An Introduction to Postmortem Photography However, our favorite pieces of hers delve into problematic social and cultural issues, such as the death and burial of individuals who have committed horrific acts, the legacy of lynching and visual culture (tw for violent images), and Re-enacting Whiteness.

You can read more of Kelly’s work on her website, and follow her on Twitter.

July 14, 2017

THE FROZEN BODIES OF MOUNT EVEREST

July 12, 2017

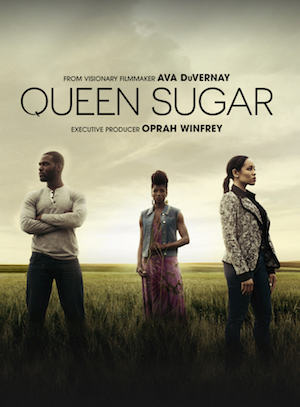

Not Just the Funeral: Queen Sugar Puts the African American Burial Tradition on Full Display

On September 6, 2016 Queen Sugar aired on the Oprah Winfrey Network (OWN). Based on the novel by Natalie Baszile, this television adaptation was co-created by acclaimed director Ava DuVernay and media mogul Oprah Winfrey. The series presents the complicated experiences of black lives in the twenty-first century and how these experiences have very real, even if invisible to most, historical underpinnings – namely American slavery – that bars present-day African Americans from land ownership, wealth building, gaining autonomy and physical independence. This legacy that American slavery has left is positioned alongside the issues of criminal activity, extra marital affair, and single fatherhood. Each play out at the intersection of race, gender, and sexuality but does not stereotype or pathologize the African American community. This has been attributed to its all-female band of directors who each direct a different episode resulting in how we see and understand , and – the main characters of Queen Sugar. As the nucleus of the show, the series tells the story of the Bordelons, an African American family who owns an 800-acre sugarcane farm in the fictional city of St. Josephine located only a few hours drive from New Orleans, Louisiana.

On September 6, 2016 Queen Sugar aired on the Oprah Winfrey Network (OWN). Based on the novel by Natalie Baszile, this television adaptation was co-created by acclaimed director Ava DuVernay and media mogul Oprah Winfrey. The series presents the complicated experiences of black lives in the twenty-first century and how these experiences have very real, even if invisible to most, historical underpinnings – namely American slavery – that bars present-day African Americans from land ownership, wealth building, gaining autonomy and physical independence. This legacy that American slavery has left is positioned alongside the issues of criminal activity, extra marital affair, and single fatherhood. Each play out at the intersection of race, gender, and sexuality but does not stereotype or pathologize the African American community. This has been attributed to its all-female band of directors who each direct a different episode resulting in how we see and understand , and – the main characters of Queen Sugar. As the nucleus of the show, the series tells the story of the Bordelons, an African American family who owns an 800-acre sugarcane farm in the fictional city of St. Josephine located only a few hours drive from New Orleans, Louisiana.

Throughout its first season, (now in its second) viewers were welcomed into the deep south to view black life lived – and lost. The second episode of the first season, aptly titled “Evergreen,” centered on the death of , the father of the siblings on which the series centers. Within this episode Ernest was not just buried, illustrated by a typical cemetery scene preceded by eulogy. Instead, the cultural aspects of death and those intrinsic characteristics present within last rites rituals were shown and directly connected to African American culture and African American death ideology. Most notably, the fact that he was bestowed Prince Hall Association of Free & Accepted Masons obsequies. Fraternal orders were not just societies but burial societies. Members pooled their money and/or paid dues covering the funeral costs of lodge brothers and their families to avoid Potter’s Fields and open air burials. Using funds to cover the costs of burial plot and interment was especially important during a time when slave holders and later Jim Crow rendered such inhumation unnecessary. The connection made between masonry and African American burial practices illustrates the importance of a proper burial complete with ceremony and earthen burial.

With Ernest’s next of kin seated gravesite, his Prince Hall F. & A. M. lodge brothers stood surrounding the casket. In full regalia complete with aprons, they read sacred texts emphasizing the immortality of Ernest’s soul and the temporary resting place that is his gravesite, further illustrated by the sprigs of evergreen that filled their pocket squares eventually placed atop the casket. Common to African American death ideology is the circle of life, of which death is part. Life is not linear with death meeting one at the end. Death is the beginning of a new life cycle where the soul will live on in the hereafter that is near and not so far off. The belief stems from Traditional African Religion where upon last breaths the deceased become spirits, Human Spirits, who live between us and God, watching and guiding us and visiting us openly or in our dreams. Our deceased kin and ancestors are kept alive, like Ernest, by memorial and the remembering done by the living.

Memory-making in the African American community has always been a very important part of death practices. During the institution of slavery, the second funeral developed from a need of a proper memorial. Unable to convene and properly remember each family and friend at the time of their death, a gathering was held later (sometimes upwards to a year) at night in order to remember all who passed. Although important, as Karla Holloway explains memory-making in the black community can be difficult and troubling. Statistically and historically speaking, the death of African Americans is a result of violence, white violence, government-sanctioned violence, and systemic inequalities found within limited housing, food options, and job choices. So, although Ernest died in the hospital as if to drift to sleep, son Ralph-Angel still does not want , his grandson, to participate in the memorial of grandfather’s death. Believed to be the continuation of life, death in the black community still directly involves the black experience which is underpinned with white supremacy – an obsession with owning and controlling black bodies. Ralph-Angel links Blue’s participation in the funeral as perhaps normalizing and even accepting his own future death from some aspect of structural racism.

, Ernest’s sister, does not see it that way. Death is a way to say a final good-bye and perhaps more importantly, a visceral way to deal healthily with the abrupt physical separation of a loved one. In the end, Blue attended the funeral, shown graveside with the others. Matching Ernest’s casket, the family, except for Blue, was dressed in all white.

While at the funeral home with her other two siblings, Nova insisted on a white casket because Ernest, according to Nova, was “our black stone, our protection” and therefore only “light [should] send him back to the light.” In many African cultures white is the color of death. White symbolizes light and just like the torches carried during the funeral processions of old, the color was meant to send the deceased onward to the next life. In ancient Greek and early Christian death culture, the deceased were buried in white or wrapped in a white burial shroud. The funeral is a ceremonious send off with the casket as the chosen vessel of transport. The ancient Egyptians believed in immaculately preserving the body because it would be reconnected with the soul to live in the afterlife. Therefore, the casket can simultaneously be viewed as a very important storage or holding unit but also a vessel to withstand the journey.

The journey comprised a deathway consistent with the creole culture from which Nova was raised – a mixture of African, French, and Caribbean. She made this very clear by insisting on sewing a closed drawstring pouch into her father’s casket. Contents unknown, but the fact that she compared her father to a “black stone” (which signals strength and protection), I believe solves this mystery. Either way, this is a death ritual derived from the African Diaspora – where parts of African death norms survived and merged with the cultures they now reside. Further still, not placing the contents on the body but directly inside the lining of the casket assumes that the pouch, and its contents, concerned the safety and completion of the journey.

Last rites, death rituals, and funeral completed, the Bordelons, like many grieving African American families, sat down for repast – a post-burial meal where the bereaved surrounded by close family and friends were put on the path to normalcy. Death is jarring but with fellowship and sustenance the grieving are comforted. Big sister Nova quickly (and very loudly) reminded little sister Charley of this when Charley solicited the services of a catering company for the repast. “We don’t honor our father by sitting friends and family outside at fancy tables…[or] by having strangers serve those grieving,” snapped Nova, “We serve comfort food to those who need comfort – and we do it with our own hands!!” Nova was hearkening to the funeral tradition where family and those close to the family performed the funerary services, especially preparing and serving food. When death strikes in the African American community, particularly in the south where the Bordelon’s reside, usually it is food that is first sent and not flowers. Cakes of chocolate, coconut and jelly and entrees of chicken, potato salad and dressing fills the decedent’s home. The repast is for the living. The living must eat and continue to live although the appetite is the first thing to go when grieving. These are the foodways that Michael Twitty uncovered while “exploring culinary traditions of Africa, African America and the African Diaspora” that is particularly illuminated in his highly anticipated book, the The Cooking Gene. Twitty traced his southern roots all the back to Africa by following ingredients and food items. On this quest, he stopped at the plantations where his ancestors were the captives and the captors, visiting their graves, and cooking meals they frequently ate. Food, but more importantly, the planned fellowship filled with caring friends and warm memories of the deceased – that is the repast – is purposeful and important to African American funerary traditions.

Ultimately, the “Evergreen” episode of Queen Sugar illustrated the importance of a proper burial in the African American funerary tradition. A proper funeral meant respectable burial with the necessary last rites dictated by African American cultural death norms. Most times elaborate with the finest hearse, a proper funeral showcased the life the person lived. Ernest was a proud Prince Hall F. & A. M. lodge member indicated by the ritualized masonic ceremony performed. From the start, it was pertinent that Ernest have a casket worthy of the journey to the afterlife and one ceremonially blessed to protect him the duration. The all white his family was cloaked and him secured in his white coffin – with black stones that protected – was like a beacon heralding him to the afterlife. The African American burial tradition emphasizes the cycle of life which death is apart and with authentic and intricate story-telling, Queen Sugar captured the mourning as well as the memorial.

Dr. Kami Fletcher is an Assistant Professor of African American History at Delaware State University. Her research centers on African American burial grounds and late 19th/early 20th century Black male and female undertakers. She is the author of “Real Business: Maryland’s First Black Cemetery Journey’s into the Enterprise of Death, 1807-1920” and “African American Undertakers & Undertaking in Baltimore, MD, 1865-1910” forthcoming in the Maryland Historical Magazine. She is also the co-editor of the forthcoming volume Till Death Do Us Part: American Ethnic Cemeteries as Borders Uncrossed which examines the internal and/or external drives among ethnic, religious, and racial groups to separate their dead, under contract with University of Mississippi Press.

Dr. Fletcher is a guest blogger for Black Perspectives where she blogs about African American female/male undertakers, African American death ideology, and the history of Black Baltimore.

For more on Dr. Fletcher, please visit her website and follow her on Twitter.

Not Just the Funeral: Queen Sugar Puts the African American Burial Tradition on Full Display

Caitlin Doughty's Blog

- Caitlin Doughty's profile

- 8409 followers