Caitlin Doughty's Blog, page 31

April 4, 2017

Walking Amongst the Dead: The Neighborhood Graves of Hong Kong

I always preferred to walk to Emi’s house rather than take the bus.

Getting off at the Kam Sheung Road MTR station in Yuen Long, I’d trek past the encampment of fruit, snacks, and goods stalls, avoid getting hit by a green and yellow mini bus screeching to a halt at the terminal, and cross Kam Sheung Road when the pedestrian light would finally change. A few times it skipped me altogether, and my palms would get a little sweatier (no small thing in the relentless humidity of Hong Kong) as I’d run across the street in front of the underpass.

Emi and her roommate Jay often asked me why I insisted on walking to their village flat instead of taking the quick, air-conditioned bus. Their neighborhood in Yuen Long, being outside of the city, in Hong Kong’s New Territories, was rather rural, full of bugs, and devoid of the usual lights and shops that people think of when they think of the glittering metropolis that is Hong Kong proper.

The few shops and businesses that dotted the the main road were auto salvage type places strewn with car parts and lazy “guard dogs”, little village shops that sold snacks, drinks, and cigarettes, and textile manufacturers or warehouses. Push a little further into one of the village enclaves and you might find tiny restaurants (there was a pizza parlor!), a pet shop, food stands, but all rather quiet and charming – but unassuming.

If you knew what you were looking for, there was a pet crematory that looked like a public restroom from the outside. The inside was actually quite warm and professional, like a Chinese grandma had decorated it. My cat had been cremated there.

But I liked the walk because it took me through part of a Yuen Long village. More specifically the graves of that village.

Crossing Kam Sheung Road I’d walk up to the river and hang a right, taking the road along the outskirts of the village. Trees shaded the street overhead, and all around me the concrete of Hong Kong was taken over by green mountains in the distance, dense plants, and overgrowth. I was constantly on the lookout for low-hanging spiders.

After about 10 minutes I’d get to the short, stone bridge that led off the street into Emi’s part of the neighborhood. The greenery became more claustrophobic, the bugs buzzed more aggressively in your ear, and the road became a rutted mix of asphalt, rocks, and earth.

The first graves stood around the bend, right after you crossed the bridge. Large, U-shaped Chinese graves, one with what appeared to be shiny metallic adornment at the top. The two largest ones, set against a mound, were probably about as tall as my five-foot-four inches at their apex. Three other smaller graves, also U-shaped were scattered about the field too.

The graves, like a little grave-family, sat in a field that was sometimes overgrown, sometimes cut down, with rocky patches poking through. There didn’t appear to be a rhyme or reason in the placement of the graves to my westernized eyes. They looked scattered but quite cozy in the field, protected from curious passersby (like myself) by a warped, rusty chain link fence.

It was hard to see if the random-seeming graves belonged to a home or the nearby temple. If anything, they seemed feral; like a band of nomadic graves that had decided that that field was a good place to plant themselves.

SOMEONE tended to them now and again, SOMEONE occasionally placed incense. It was a mystery I was happy to be a passive observer of, just grateful that I got to say hello from time to time.

I’d continue down the curved, bumpy road past a high, red wall with gold Chinese characters on it. In showing a picture to my mom – who can actually read Chinese, unlike me who is sadly illiterate in my family’s mother tongue – she said that it was a Buddhist temple, and that just seeing some part of the writing on that red was was supposed to be good luck. I wonder if this temple had something to do with the graves in the area?

Smaller graves popped up on either side of the road as I continued to Emi’s.

To the left, off of what looked like a driveway canopied in trees, was a tiny headstone that jutted out at an odd angle. It looked like it might have had abbreviated, sloping, U-shaped arms at one point – a micro version of the graves in the field – but its placement over tree roots had long since crumbled the architecture.

Other relatively small, conservative graves would pop up here and there in fields or peeking out of overgrown grass and plants at a fork in the road. Some looked forgotten, some might have only been masquerading as forgotten. I can’t be sure, but I suspect many of these graves were illegal.

As one of the most crowded places on earth, space for the living in Hong Kong, let alone the dead, is scarce.

In Yuen Long specifically, there has been tension between the government and the indigenous people. While people are supposed to get permission create a burial ground or dig a grave, the lack of land availability (and frankly, the government’s lack of attention to the matter) has led many illegal graves and cemeteries to pop up in the more remote New Territories.

In parks, on small farm plots, the middle of wooded areas – discovering the odd grave in rural Hong Kong was not actually that odd. While hiking through a park that surrounded a reservoir in New Territories, I spied a handful of graves on the hillside and hidden amongst the trees. A couple were huge, hulking Chinese graves whose arms easily reached 20 feet across and six to eight feet tall. While these larger ones may have been legal, belonging to old families in the community, the smaller, more discrete ones probably were not.

But with long wait lists for the enormous multi-level cemeteries in Happy Valley or on Mount Davis, even for one of the city’s many columbaria, many Hong Kongers have taken to burying where they can.

My favorite grave on my “grave walk” through Emi’s village was a medium-sized Chinese grave that was all but toppling into a ditch. Situated right next to where it seemed the neighborhood set out their recycling, the grave sat slanting on a triangular patch of grass and dirt just a few feet off the side of the road.

It looked like the ground on one side of it had collapsed, creating a shallow trench. Yet the grave obstinately clung on, remaining intact.

Its headstone was about chest high on me, with it’s short arms stubbornly holding onto the earth, reaching about four feet across at its widest. While it appeared that someone was lackadaisically clearing it of debris from time to time, it looked largely unkempt; rogue recycling and dead plants would often all but obscure it.

I liked that grave. It looked like it had no business being there, yet it refused to budge. It was scrappy. It was like saying hello to a friend every time I walked by.

But one evening in early spring my friends got a makeover.

You see, Hong Kong cemeteries had sprung to life for Ching Ming or the Grave Sweeping Festival. During this time of year, in the third month of the lunar calendar (typically around April 5th, this year it’s April 4th), Chinese people in China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Macau among other places take to graves and tombs to clean them up. It is the first of two Grave Sweeping festivals, the other being Chung Yeung in the fall.

During Ching Ming graves are cleaned and tended to, but more than that, ancestors are honored and respected.

I remember passing by a cluster of random-seeming graves near a roundabout in Yuen Long. Situated on a hill, Chinese and western style graves dotted the terrain. I suspect this was one of the more official burial grounds.

Families carefully cleaned up the graves with intensity and focus. One woman scrubbed a headstone with a rag, another cleared weeds. Smoke filled the air as incense and paper “Hell money” (a translation not indicative necessarily of the Christian Hell), paper clothes, paper food and drink, even paper cell phones were burned so the dead could use them in the afterlife.

Side query: Who do the dead call? What if they want to call another dead person but that person’s family wasn’t considerate enough to burn a phone for them? What if that family burned them a shoddy flip phone, and that dead person’s best pal wants to send them a hilarious video of a ghost kitten? What is the afterlife without hilarious cat videos? One can only hope that the flip phone ghost’s family also burned a paper iPad for them.

There are entire shops in Hong Kong devoted to the sale of burnable paper goods for the dead. You all can burn a paper TV (with paper Netflix) for me someday, with a six pack of paper San Miguel beer and a paper pizza.

Food (real not paper) is offered too. Loved ones will bring entire feasts to graves, complete with wine. The point is to let the dead know that they have not been forgotten, and to make sure that they have everything they might need in the afterlife. To believers, not doing so is asking for retribution from the dead. This is Chinese after-death care.

Along with the Hungry Ghost Festival in late summer and Chung Yeung in the fall, I loved Hong Kong’s commitment to remembering the dead. I loved the way death and the dead were never permitted to be forgotten. A few times a year the dead were brought to the forefront. Either because the air would be thick with incense and burnt offerings (my urban street in the neighborhood of Jordan would be foggy with smoke during the Hungry Ghost Festival), or because your friendly neighborhood graves would come to life – one would be hard-pressed not to let the dead cross your mind.

Death, the dead, and how we regard them was never far from the cultural conversation.

But back to my friends.

During that early spring evening, I was walking to Emi’s wondering if I should have brought two bottles of wine instead of one for the group that was gathering, when after crossing the stone bridge, the family of graves caught my eye.

Someone had tidied them up (they were almost gleaming), cut the grass around the graves, and flecks of light from burning incense by the headstones glowed in the pink Hong Kong twilight. I always loved how Hong Kong turned pink, or sometimes blue, as night fell.

Adorning the graves were flowers, remnants of brightly colored paper, some fruit, and piles of ash. The family looked all dressed up.

Down the road my favorite grave looked like the belle of the ball. If the ball was in an overgrown ditch. But who’s judging? Like I said, that grave was scrappy.

The overgrowth had been cleared from the grave, and its marble headstone was actually reflective and clear of candy wrappers. While its arms sagged, you could actually see the gray-pink in the stone, and the formerly dirt-caked words carved into it were crisp and clear. It was like the old gal got a facial.

Incense glowed at the grave’s base, next to a full, fresh beer bottle and a soft drink can. A little glass container of clean water sat a little ways away from the beverages.

Seeing this leaning grave looking so cared for sparked a surprising amount of emotion in me. I couldn’t stop from smiling, and as I stood alone, creepily grinning at a grave at the side of the road in the near-dark, a lump grew in my throat.

I didn’t know this dead person, I didn’t have any real connection to this grave other than the fact that I liked it, and had anthropomorphized it into this weird, tough, lady-grave who HAD SEEN SOME THINGS, I TELL YOU WHAT.

But I was delighted to see her – I’ve been resisting calling the grave “her” this whole time, but WHATEVER, we’re past any professional distance at this point – getting some care. She wasn’t forgotten.

Whoever was buried in that grave, Ching Ming had given their loved ones cause to think of them and attend to them (even if out of duty). That dead person was important a few times a year.

And who knows, maybe that off-kilter roadside grave had more fans than just myself? Maybe that neighborhood grave was just one of several fond reminders of mortality for the community?

I know that those random Yuen Long graves are probably not long for Hong Kong. Eventually the argument that people can’t just bury their dead where they feel like it will be won, and the those village graves will either be exhumed and moved, leveled, or left to crumble. The graves will die too.

But until then the graves, not sequestered away in some gated cemetery or remote graveyard, are a normal part of life in Yuen Long. Amidst the growing number of modern apartments that are overtaking the low, squat houses and boxy, two-story village homes, lie a scattering of tenacious graves that don’t actually seem out of place. Life and death mingle quite nicely.

When I would be walking to Emi’s, feeling more alive than ever, there was a peacefulness in encountering those graves. Maybe the people interred, my “friends”, had walked the same path I had; had even noticed some of the same graves I noticed?

On those quiet solo walks, the dead of Yuen Long became an important and precious part of my life, and it was an honor to remember them.

Louise Hung is an American writer living in Japan. You may remember her from xoJane’s Creepy Corner, Global Comment, or from one of her many articles on death, folklore, or cats floating around the Internet. Follow her on Twitter.

Walking Amongst the Dead: The Neighborhood Graves of Hong Kong

March 31, 2017

CREMATORY SCANDAL THAT CHANGED THE DEATH INDUSTRY

March 28, 2017

Grave Diggers & Body Washers – Great Women In Death History

In 1887, it seemed as though one funeral procession passed by the Orton house each day. Inside, all seven Orton children had come down with diphtheria. The DuBrutz family in the next town over had already lost five of their children to the epidemic, believed to have been caused by miasma – the terrible stench that emanated from the thousands of dead cattle and sheep covering the plains after the rains came that year. The pioneer families of Central California were dying so fast people resorted to taking apart their barns to provide wood to build coffins for their loved ones.

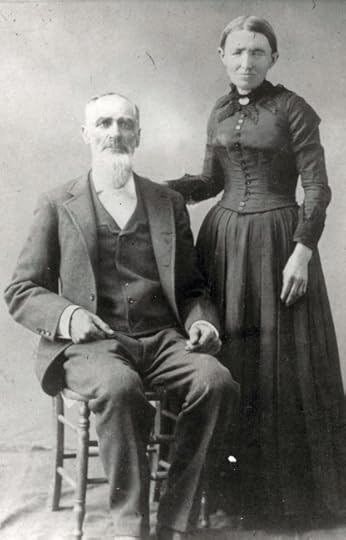

Julius and Lucretia Orton

Windows were boarded up and people shut themselves away within their homes for fear of contracting ‘the plague.’ Neighbors dared not help one another, fearing contact with others would cost them their lives, leaving people isolated and alone in their grief to carry out the tasks of preparing and caring for their dead.

Only one woman in the county dared to enter their homes to lay out and bury the children when they died – Katherine Burns. Armed with a medicine that was “so powerful it would eat holes in clothes on which it dropped” (Ina Stiner, Early Family Histories), a washing tub to bathe in, and an extra set of clean clothing for herself, Burns took on the death work no one else would.

The first cemetery in Lindsay

I first uncovered the story of Katherine Burns when I was hired on to be the curator of a small, Central California farming town’s first historical museum. Then I was asked to write the first book dedicated to their local history. I didn’t expect to find much beyond infighting among farmers and maybe some interesting agricultural innovations. I certainly didn’t expect to find much in terms of women’s contributions.

I was wrong.

The contributions of women in the community were ample, and impressively death oriented.

In the newly forming town of Lindsay, the small population of just a few hundred was rapidly diminishing during the epidemic. A local farmer offered to donate land to create the first communal cemetery in the area, however, no one volunteered to claim the deed, and with it the responsibility for the town’s deceased. In the end, it was a 20-year-old woman, Miss Kincaid, who took possession of the land and established the first cemetery. She did the grounds keeping, record keeping and even dug the graves.

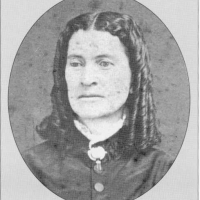

Mary Graves

In the 1930s Lindsay’s Orange Blossom Queen, Charlotte Bequette, was the daughter of a wealthy rancher and considered “the Belle of Lindsay.” What they didn’t know was that her grandmother was once known as “the Belle of the Donner Party.” She was Mary Graves, a surviving member of the ill-fated Donner Party – you know, the pioneers that got snowbound and tuned to cannibalism? Yes, that Donner party.

Shortly after Graves’ rescue she married Edward Gant Pyle and they moved to San Jose, California where she became the first female teacher there. However, their joy was short-lived when Pyle went out one day and never returned home. His body was found, almost a year later – he had been murdered. Pyle’s killer was captured and imprisoned. While the murderer awaited execution, Graves stayed at the jail, tended his wounds, cooked his food and kept watch over him – all of this to ensure he survived long enough for her to watch him hang.

Discovering these stories of women largely forgotten by the communities they served, engaging in various aspects of death work or confronting their mortality in my own backyard prompted me to wonder how many other stories there were? So, for the past two years I have been uncovering extraordinary stories of women who have done the same:

The first female undertaker in the U.S. who was active in the Underground Railroad.

The Empress Consort who had her corpse laid out to decompose on a busy street to teach others the value of contemplating one’s own mortality.

The librarian who spent her lifetime identifying thousands of immigrants who perished as a result of a natural disaster, while exposing the men trying to hide those deaths to make a profit.

Over the next several months, I look forward to sharing their stories, alongside many others, in a new series here at The Order – Great Women in Death History.

Sarah Chavez is the executive director of The Order of the Good Death and co-founder of Death & the Maiden, a project that endeavors to explore the historical and cultural roles women have played in relation to death. She also has a blog, Nourishing Death, which examines the relationship between food and death in rituals, culture, religion and society. You can follow her on Twitter .

March 25, 2017

All That Is Solid Melts Into Air

“The most popular use of the photograph

is as a memento of the absent.”

— John Berger

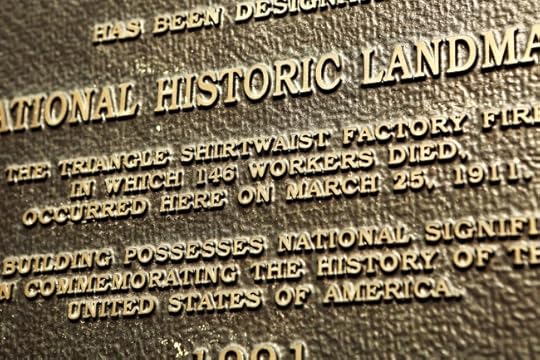

The intersection of Greene Street and Washington Place.

“Can I help you?”

That sentence, always a preamble to being thrown out of a place I’m not supposed to be, is one I’ve been half expecting all morning.

A construction worker who’s wearing so much orange that I’ve nicknamed him ‘Julius’ (in reference to the once-ubiquitous Orange Julius stands that used to be in every mall), is orbiting me from a distance. I think he doesn’t realize how much the eye-watering color (and the amount of it) makes him stand out. Bright orange vest. Bright orange flag. And, in a very stylish touch, bright orange Adidas sneakers. I’d like to think he’s simply admiring the Da-Glo orange tags on my equipment bags — I share a love of orange — but I’m wary.

He’s been clocking me ever since I arrived at the intersection of Greene Street and Washington Place, a couple hours ago.

The street and sidewalk have been blocked off for repair, and as I said above, I’m trespassing. Conspicuously so: I have a medium-format camera, mounted to a tripod with the lens pointing straight up, which I’ve been moving around the block. I’m using an old-fashioned cable release, so my old-school Hasselblad sounds like a mousetrap when it goes off. Subtlety is not part of my M.O.

For the most part, Julius has contented himself with keeping an eye on me, as he does his work. I just keep on shooting, taking his lack of approach as tacit permission to continue. I hope to net nearly 150 unique images from these streets and sidewalks.

At one point, I look up from my viewfinder and there he is, standing next to me.

“Can I help you.”

I shrug: “Oh, I’m good. Just grabbing shots.” I point up:

“What’s up?”

“Clouds.”

“For real?”

“Yep.”

“Listen, man. I’m sorry, but—”

I’m saved by a horn blast – a LOUD one – from a dump truck. The honk is for Julius — the driver is yelling that he needs to be guided in — and the truck starts beeping as it slowly backs down Greene Street. Julius unfurls his orange flag, saying:

“Just…stay on the sidewalk, alright?”

A bit of luck. And, more importantly, more time to shoot.

A follow-up question might have included asking why I intentionally sought this particular corner to photograph clouds. It is frames by buildings and a couple trees. Washington Square Park, with its almost entirely unobstructed views of the sky — is only a half-block away.

But then, I wouldn’t be memorializing the 146 people who died here.

• • •

Over the past nine years, I’ve traveled to the locations of people’s violent deaths, and photographed the sky above.

The series title is All That Is Solid Melts Into Air.

I’ve chosen to document only the skies because they are an element common to every location, yet exist at a remove from ‘concrete’ demarcations. The skies will still be here long after structures, landmarks and addresses have become altered or disappeared entirely. What I’ve photograph will never be the same sky as when the death occurred (much like the section of river where someone has drowned); and that is an essential point of the series. Something happened, but the world moves (and has moved) on. Nature is oblivious to our predicaments, unconcerned with the ‘rightness or wrongness’ of events.

As Heraclitus (from whom I borrow the river metaphor above) so elegantly put it: “There is nothing permanent except change.”

This project has taken me to both dangerous areas well-known for high mortality rates and quiet neighborhoods generally considered safe. Some of these places were obviously threatening, others were stunningly beautiful. Most often they were nondescript places, with nothing to distinguish them as the site of a tragic occurrence. Like this Greenwich Village block. It’s the site of a horrific tragedy. If you look on the building walls, you’ll find a plaque (ignored by most passerby) identifying this building, now part of the NYU campus, as the former address of the Triangle Shirtwaist Company.

On March 25th, 1911, 123 women and 23 men died here when a fire broke out. The owners had locked exit doors, to discourage workers from taking breaks. Most of those who died did so after jumping from the 8th, 9th and 10th floor windows to avoid the heat and flames. Those who wouldn’t or couldn’t jump died inside, trapped on the factory floor.

The descriptions are graphic and vivid. A witness, Louis Waldman, recalls seeing “girl after girl appear at the reddened windows, pause for a terrified moment, and then leap to the pavement below, to land as mangled, bloody pulp. This went on for what seemed a ghastly eternity. Occasionally a girl who had hesitated too long was licked by pursuing flames and, screaming with clothing and hair ablaze, plunged like a living torch to the street. Life nets held by the firemen were torn by the impact of the falling bodies. The emotions of the crowd were indescribable. Women were hysterical, scores fainted; men wept as, in paroxysms of frenzy, they hurled themselves against the police lines.”

A reporter said: “I learned a new sound that day, a sound more horrible than description can picture — the thud of a speeding living body on a stone sidewalk.”

Triangle Shirtwaist is considered to this day to be one of the worst industrial disasters in US history. Its impact on the public in 1911 was as profound as the World Trade Center attack was ninety years later. But the cause of the 1911 tragedy was not an enemy ideology or attack; it was simple, careless greed. And it became a driving force behind the growth and resolve of unions in New York City, then the United States.

• • •

The dump truck has unloaded, and roars away. Julius is heading back to me, but his body language is more casual than before.

The dump truck has unloaded, and roars away. Julius is heading back to me, but his body language is more casual than before.

“So, why clouds, man?”

I actually decide to just tell him. I point out the plaque.

Then (because he asked) I show him documentation of some of my previous installations on my iPhone.

When I exhibit the series, the photographs are mounted overhead (the angle of capture) with pertinent information (name, age, cause of death, GPS coordinates) engraved in survey markers embedded directly below the corresponding image.

Basically, a cenotaph. But it also happens to function as a kind of chapel, a subjective ‘Rorschach Test’ for belief systems:

“As you can see — they’re all at peace now…” (priest).

“As you can see — there’s nothing!” (atheist).

“As you can see — all is interconnected.” (Buddhist).

Interestingly, science simultaneously backs up the Buddhist view even as it indicates that these images may actually be more representative than they initially seem. On a molecular level, elements which brushed against and passed through our matter will still exist in the world after we’ve gone.

Neil DeGrasse Tyson put it so:

“There are more molecules of water in a cup of water than cups of water in all the world’s oceans. This means that some molecules in every cup of water you drink passed through the kidneys of Genghis Khan, Napoleon, Abe Lincoln or any other historical person of your choosing.”

“The same goes for air: there are more molecules of air in a single breath of air than there are breaths of air in Earth’s entire atmosphere. Therefore, some molecules of air you inhale passed through the lungs of Billy the Kid, Joan of Arc, Beethoven, Socrates or any other historical person of your choosing.”

It stands to reason, then, that my images of skies and clouds (air + water) have captured a tiny bit of matter that has brushed by everyone. As the Baghavad Gita says: “They live in wisdom who see themselves in all and all in them.”

• • •

To my happy surprise, Julius is into it. And has become an ally. He lets me shoot well into the afternoon. And asks a lot of questions. Good ones. Sometimes after I answer, he’ll wander back to the worksite, then come back, asking a followup, like:

“What the hell made you start doing this?”

It’s a long story, Julius.

The original concept for this project emerged as I reflected on the site of a Japanese-run concentration camp in Indonesia, the Djakarta camp. My mother was a prisoner there from ages 8 through 12, and was among those scheduled to be marched into quicksand as the war wound down and supplies ran low. The camp officials simply couldn’t afford the supplies to feed them or the bullets to shoot them. According to camp records, had the 2nd atomic bomb not been dropped on Nagasaki (prompting immediate surrender in this area of the Pacific), she and everyone else would have been executed, and I wouldn’t be writing this.

So, it’s a place with significant meaning to me, and one to which I have often thought of making a pilgrimage.

Except, it isn’t really there anymore.

Unlike the European death camps (particularly the infamous Polish ones), or former Rwandan churches (where victims were lead to their deaths by the nuns and priests), Most of these Indonesian camps have disintegrated with neglect. And, unlike NYU, the Indonesians didn’t put up plaques. Many of those locations are now nondescript, reclaimed by the jungle. Which underlined to me how landscape is undergoing continual change.

I began to apply the idea to local deaths in Los Angeles, then in other places I’d travelled. My method in learning of these locations has, of course, shaped the content. Death from natural causes is rarely reported, excepting cases of celebrity or political power. Most of the incidents I become aware of have an extraordinary component. In any large city, someone having a fatal heart attack really isn’t news; that person then crashing the private plane they were piloting into a residential neighborhood is.

So, most of the stories I become aware of are heightened ones. And that factor becomes part of the way a viewer processes the image of the cloud I’ve made.

• • •

Interestingly, there is a long history of clouds being used to communicate intense emotion, expressionistic power, and the ineffable. Modernist photographer Alfred Stieglitz used clouds as a way of communicating purely abstract form and emotion in his Equivalents series, although he became coy when pressed whether or not he meant to represent divinity:

“Some feel I have photographed God,” he wrote to Hart Crane in 1923, adding: “maybe.”

Master landscape painter John Constable (1776-1837), stranded in unfamiliar countryside with his beloved wife Maria (they’d moved outside London for her health as she succumbed to tuberculosis), began ‘skying’ – painting studies of the skies above Hampstead Heath. None of these were exhibited while he was alive; all are prized by collectors now. Though Constable took a thorough, empirical approach (noting time, weather, time of year, type of cloud; these dramatic vistas have always been thought of as representations of intense emotion. Constable then applied this skill and the subtext to his landscapes. Using the textures of the skies to comment on and shape the viewer’s impression of the vistas depicted. The Metropolitan Museum of Art notes: “landscapes from the time of his wife’s death feature dark, turbulent skies that carry the brunt of the works’ emotional weight.”

The late, indispensible art critic John Berger, in his seminal Ways of Seeing, created a powerfully simple exercise to demonstrate the impact of this kind of context, using Van Gogh’s Wheatfield with Crows. First, Berger shows the painting. Then, this sentence: “This is the last painting Van Gogh made before he killed himself.”

Then Berger shows the painting again.

He then says: “It is hard to define exactly how the words have changed the image, but undoubtedly they have.”

“The image now illustrates the sentence.”

• • •

All That Is Solid Melts Into Air represents myriad things: Individual portraits of absence. An expressionistic link to a tragic occurrence. An investigation of the overt correlation between a photograph and its context. An angle of view perhaps in line with the last perspective of a person leaving this world. A Memento Mori. Collectively, a signifier of the world beyond reason.

Look up, and you will see it all yourself.

• • •

My intent is that the images I photographed in October of 2015 will illustrate the following 146-part sentence, written 106 years ago today, and now part of the book of the universe:

Adler, Lizzie, 24

Altman, Anna, 16

Ardito, Annina, 25

Bassino, Rose, 31

Benanti, Vincenza, 22

Berger, Yetta, 18

Bernstein, Essie, 19

Bernstein, Jacob, 38

Bernstein, Morris, 19

Billota, Vincenza, 16

Binowitz, Abraham, 30

Birman, Gussie, 22

Brenman, Rosie, 23

Brenman, Sarah, 17

Brodsky, Ida, 15

Brodsky, Sarah, 21

Brucks, Ada, 18

Brunetti, Laura, 17

Cammarata, Josephine, 17

Caputo, Francesca, 17

Carlisi, Josephine, 31

Caruso, Albina, 20

Ciminello, Annie, 36

Cirrito, Rosina, 18

Cohen, Anna, 25

Colletti, Annie, 30

Cooper, Sarah, 16

Cordiano , Michelina, 25

Dashefsky, Bessie, 25

Del Castillo, Josie, 21

Dockman, Clara, 19

Donick, Kalman, 24

Driansky, Nettie, 21

Eisenberg, Celia, 17

Evans, Dora, 18

Feibisch, Rebecca, 20

Fichtenholtz, Yetta, 18

Fitze, Daisy Lopez, 26

Floresta, Mary, 26

Florin, Max, 23

Franco, Jenne, 16

Friedman, Rose, 18

Gerjuoy, Diana, 18

Gerstein, Molly, 17

Giannattasio, Catherine, 22

Gitlin, Celia, 17

Goldstein, Esther, 20

Goldstein, Lena, 22

Goldstein, Mary, 18

Goldstein, Yetta, 20

Grasso, Rosie, 16

Greb, Bertha, 25

Grossman, Rachel, 18

Herman, Mary, 40

Hochfeld, Esther, 21

Hollander, Fannie, 18

Horowitz, Pauline, 19

Jukofsky, Ida, 19

Kanowitz, Ida, 18

Kaplan, Tessie, 18

Kessler, Beckie, 19

Klein, Jacob, 23

Koppelman, Beckie, 16

Kula, Bertha, 19

Kupferschmidt, Tillie, 16

Kurtz, Benjamin, 19

L’Abbate, Annie, 16

Lansner, Fannie, 21

Lauletti, Maria Giuseppa, 33

Lederman, Jennie, 21

Lehrer, Max, 18

Lehrer, Sam, 19

Leone, Kate, 14

Leventhal, Mary, 22

Levin, Jennie, 19

Levine, Pauline, 19

Liebowitz, Nettie, 23

Liermark, Rose, 19

Maiale, Bettina, 18

Maiale, Frances, 21

Maltese, Catherine, 39

Maltese, Lucia, 20

Maltese, Rosaria, 14

Manaria, Maria, 27

Mankofsky, Rose, 22

Mehl, Rose, 15

Meyers, Yetta, 19

Midolo, Gaetana, 16

Miller, Annie, 16

Neubauer, Beckie, 19

Nicholas, Annie, 18

Nicolosi, Michelina, 21

Nussbaum, Sadie, 18

Oberstein, Julia, 19

Oringer, Rose, 19

Ostrovsky , Beckie, 20

Pack, Annie, 18

Panno, Provindenza, 43

Pasqualicchio, Antonietta, 16

Pearl, Ida, 20

Pildescu, Jennie, 18

Pinelli, Vincenza, 30

Prato, Emilia, 21

Prestifilippo, Concetta, 22

Reines, Beckie, 18

Rosen (Loeb), Louis, 33

Rosen, Fannie, 21

Rosen, Israel, 17

Rosen, Julia, 35

Rosenbaum, Yetta, 22

Rosenberg, Jennie, 21

Rosenfeld, Gussie, 22

Rothstein, Emma, 22

Rotner, Theodore, 22

Sabasowitz, Sarah, 17

Salemi, Santina, 24

Saracino, Sarafina, 25

Saracino, Teresina, 20

Schiffman, Gussie, 18

Schmidt, Theresa, 32

Schneider, Ethel, 20

Schochet, Violet, 21

Schpunt, Golda, 19

Schwartz, Margaret, 24

Seltzer, Jacob, 33

Shapiro, Rosie, 17

Sklover, Ben, 25

Sorkin, Rose, 18

Starr, Annie, 30

Stein, Jennie, 18

Stellino, Jennie, 16

Stiglitz, Jennie, 22

Taback, Sam, 20

Terranova, Clotilde, 22

Tortorelli, Isabella, 17

Utal, Meyer, 23

Uzzo, Catherine, 22

Velakofsky, Frieda, 20

Viviano, Bessie, 15

Weiner, Rosie, 20

Weintraub, Sarah, 17

Weisner, Tessie, 21

Welfowitz, Dora, 21

Wendroff, Bertha, 18

Wilson, Joseph, 22

Wisotsky, Sonia, 17

David Orr is a visual artist based in Los Angeles. His work has been shown extensively in the United States and internationally, and is in public collections among such artists as Ansel Adams, John Baldessari, Jim Dine, David Hockney, The Brothers Quay, Edward Weston, and Joel-Peter Witkin.

All That Is Solid Melts Into Air is an ongoing project; as of this writing over 300 locations have been photographed worldwide.

You can follow David on Instagram and Facebook

March 24, 2017

ASK A MORTICIAN – The Self Mummified Monks

March 21, 2017

Confronting Mortality In Trunyan

The small village of Trunyan sits on the eastern shore of Bali’s Lake Batur and in the shadow of the island’s most famous volcano, Mt. Batur. This area is less than two hours from the tourist hubs of Ubud and Kuta, but by Balinese standards it is remote and it seems a world away from the bustle of those cities. Things are different here. Trunyan and the surrounding villages are tranquil, and traditional ways of life linger largely unchanged.

Visitors to the cemetery find an offering plate and pair of skulls waiting to greet them at the entrance. In the background, the base of the famous banyan tree is visible.

Visitors come only in a trickle, maybe a handful a day. And those who come are following a different itinerary than those who seek in Bali a tropical paradise, because the idyll that the island represents for foreigners is here given rebuke by Trunyan’s greatest tourist attraction, its unique cemetery. Throughout the rest of Bali, the dead are cremated, but in Trunyan mortality openly confronts paradise with a visible spectacle of human decay.

Situated on the lake shore and surrounded by dense jungle, the cemetery is accessible only by boat. Those arriving find an offering plate and pair of skulls waiting to greet them as a precursor to the hundreds more that are waiting on the cemetery ground itself. The people of Trunyan administer not so much a cemetery as a large charnel ground where hundreds of moss green skulls are visible around and atop a stone ledge, and unknown quantities more lie in the thick brush of the surrounding jungle. And in an opening adjacent to the wall, crude latticework bamboo cages stand in a row and hold still rotting corpses, some fresh enough to identify facial details, others far along enough in decay to be scarcely more than skeletons. This is the Trunyan way: the body is allowed to publicly rot, and when that process is complete the bones are added to the pile containing those of their relatives and fellow villagers.

Situated on the lake shore and surrounded by dense jungle, the cemetery is accessible only by boat. Those arriving find an offering plate and pair of skulls waiting to greet them as a precursor to the hundreds more that are waiting on the cemetery ground itself. The people of Trunyan administer not so much a cemetery as a large charnel ground where hundreds of moss green skulls are visible around and atop a stone ledge, and unknown quantities more lie in the thick brush of the surrounding jungle. And in an opening adjacent to the wall, crude latticework bamboo cages stand in a row and hold still rotting corpses, some fresh enough to identify facial details, others far along enough in decay to be scarcely more than skeletons. This is the Trunyan way: the body is allowed to publicly rot, and when that process is complete the bones are added to the pile containing those of their relatives and fellow villagers.

This display makes Trunyan far and away Bali’s most intriguing cemetery, but a lack of record keeping by locals and a paucity of research by outsiders has made it impossible to accurately trace its history. Accounts of the site offered by villagers vary wildly, but they all agree that burials here date back a very long time, with some dating the period in centuries, others in millennia. While such responses come across as exaggerated guesswork, they may not be entirely without substance.

When the Hindu Majapahit Empire invaded Bali in the first half of the fourteenth century, most of the island was conquered, save for the area around Trunyan, which held out as the lone place in which external customs and belief systems were not imposed. The locals here consider themselves the Bali Mula, or the authentic Balinese, indigenes who have for centuries preserved the original culture of the island. In terms of Balinese funerary practice, cremation was a foreign custom brought by the Hindus, but it never caught on in Trunyan since it was believed that Mt. Batur was a kind of fire god and considered humans burning the body to be a usurpation of his authority

When the Hindu Majapahit Empire invaded Bali in the first half of the fourteenth century, most of the island was conquered, save for the area around Trunyan, which held out as the lone place in which external customs and belief systems were not imposed. The locals here consider themselves the Bali Mula, or the authentic Balinese, indigenes who have for centuries preserved the original culture of the island. In terms of Balinese funerary practice, cremation was a foreign custom brought by the Hindus, but it never caught on in Trunyan since it was believed that Mt. Batur was a kind of fire god and considered humans burning the body to be a usurpation of his authority

Thus while tourist websites and guidebooks typically consider the display of corpses and bones at Trunyan as an eccentric custom that seems out of place on Bali, the truth is exactly opposite. What goes at Trunyan is as authentically Balinese as it gets: it’s an indigenous funerary custom that may date all the way back to the Neolithic sects that introduced agriculture and tool making to the island. For the early inhabitants around Lake Batur, the essence of native spirituality was in attaining equilibrium between the visible and non visible, the natural and supernatural. They considered an open confrontation with death and the visible action of the body being reclaimed by the earth to have a natural place in such a system, and at Trunyan that tradition still perseveres and provides a window onto a custom was once much more widely spread.

There are other misconceptions about the Trunyan cemetery. In fact, it is not the only resting place used by the villagers. It is the primary cemetery and considered the “normal” one, for people whose deaths do not involve unusual or unexpected circumstances. Basically, this means it is the final resting place specifically for people who die from old age, conditions which are associated with being elderly, and various common maladies. But two other small cemeteries are also maintained. One is for people who die due accident or foul play. Their deaths are considered to be polluted, and their spirits unfulfilled, in distress, and potentially hostile. The other cemetery is for babies and young children, who are considered to be god-like due to their lack of worldly corruption.

The idea that the bodies are left out to rot is also deceptive. In the two smaller cemeteries, the deceased are buried, and even in the principal cemetery not all bodies are left out–unmarried people are supposed to be buried here, although this is in fact a very rare occurrence since the overwhelming majority of locals take a spouse. And in the case of the corpses seen openly decomposing, there is a motivation beyond simply watching nature take its course. The real point of this custom is to place the dead under the protection and auspices of a large banyan tree that is considered sacred. This special tree, which towers over the cemetery ground, serves as a home for the spirits of the dead. It also emits a perfumed odor which was considered so notable that it garnered for the tree in the distant past the name Teru Manyan, literally meaning “nice smell”–that name has since been shortened to Teruyan, the very word from which Trunyan derives.

In other words, this tree is of such importance in local folklore and spirituality that the entire locale is named after it, and its famous scent is said to have the power to sweeten even the stench of rotting flesh. Whether or not one chooses to believe the scent is supernatural, it is nevertheless true that the tree and the blanket of leaves it drops mask the odor of the cemetery’s corpses. The result is a consistently fresh and clean scent–and proof for the locals of the magical properties of both the tree and the cemetery.

The deceased brought to this blessed ground can only enter on what are considered propitious days. Due to complexities within the Balinese calendar system (there are simultaneously two calendars, one of 210 days and the other a twelve month calendar based on phases of the moon), this could mean a waiting period in the home of up to a month. According to local mythology, Mt. Batur disapproves of women moving corpses, and a natural disaster might occur if they are involved, so only men are allowed to carry the body. The men who bring the deceased to the cemetery will also dig a shallow indentation around the contour of the corpse, to help it decompose into the soil. The triangular latticework cages will then be erected, to keep birds who feast on carrion from pecking at the body.

The deceased brought to this blessed ground can only enter on what are considered propitious days. Due to complexities within the Balinese calendar system (there are simultaneously two calendars, one of 210 days and the other a twelve month calendar based on phases of the moon), this could mean a waiting period in the home of up to a month. According to local mythology, Mt. Batur disapproves of women moving corpses, and a natural disaster might occur if they are involved, so only men are allowed to carry the body. The men who bring the deceased to the cemetery will also dig a shallow indentation around the contour of the corpse, to help it decompose into the soil. The triangular latticework cages will then be erected, to keep birds who feast on carrion from pecking at the body.

There is room for eleven bamboo cages on the cemetery ground–the number eleven is considered powerful in local numerology (the local temple has likewise eleven pagodas), so more than that are not permitted. If a twelfth is needed, the oldest corpse will have its remains moved to the pile. In practical terms, given that only a couple thousand people live among the villages that use the cemetery, it is rare that space will be needed for more than eleven fresh bodies at one time, and under normal circumstances the bones will be moved to the charnel ground when it is decided the flesh is thoroughly decomposed. In the heat and humidity of the jungle, this can happen in about a year.

A 2000 rupiah note left as an offering. It’s not uncommon to find small denominations of paper money folded up among the skulls (2000 rupiah is approximately 15 US cents).

As a notable curiosity on an island with a huge tourist industry, the Trunyan cemetery has over the past few decades received increasing numbers of visitors. In the process it has inadvertently wound up causing a certain amount of consternation–not so much among the Balinese, but with foreigners. The villagers charge outsiders to see the grounds, and many visitors have found their prices to be extortive. Some tourists have expressed disgust, both in online forums and in print, with what they consider unfair fees demanded by the locals, and the best selling tourist guidebook to Bali, published by Lonely Planet, has in the past even gone so far as to declare Trunyan unwelcoming and urged people to not go there. In the most recent edition, the issue of “huge fees” is still enough of a sticking point that the book advises its readers to pass on the cemetery, writing off a fascinating indigenous funerary tradition as merely a “ghoulish spectacle.”

Considering this negative reaction, it’s important to provide a context for the fees that are charged. Technically, they are not for entry to the cemetery, but payment for the boat ride. In the past, the boat would have to go a long distance across Lake Batur, but a modern road leads directly to the center of the Trunyan so the ride is now quite short. Nevertheless, those who wish to see the cemetery are currently asked for upwards of 50 US dollars or more, and villagers are unlikely to negotiate far below their initial price, using the claim that the government owns the boat and there are certain fees the locals themselves have to pay for its use.

Considering this negative reaction, it’s important to provide a context for the fees that are charged. Technically, they are not for entry to the cemetery, but payment for the boat ride. In the past, the boat would have to go a long distance across Lake Batur, but a modern road leads directly to the center of the Trunyan so the ride is now quite short. Nevertheless, those who wish to see the cemetery are currently asked for upwards of 50 US dollars or more, and villagers are unlikely to negotiate far below their initial price, using the claim that the government owns the boat and there are certain fees the locals themselves have to pay for its use.

Those who complain are correct in pointing out that in terms of the local economy this is a relatively steep price, although in global terms it seems unfair to consider such amounts as extortive. And it is in fact true that the government gets a cut. The office in charge of local tourism does own the boat and the amount going to the village is only 60 percent of what is paid. In addition, the same office has expressed a concern about the potential deleterious effects of allowing tourism to develop too rapidly at the Trunyan cemetery, thus providing a further incentive not to lower the prices charged to outsiders, with the idea being that it is in the cemetery’s best interests to receive fewer tourists paying a higher price than to have a deluge of them paying only a few dollars.

Some Westerners have also expressed anger over other visitors playing with the skulls, moving them, and holding them up in order to pose for selfies in order to shock their friends back home. This concern, which is no doubt well intentioned, is misplaced The locals don’t particularly mind people handling the bones of their ancestors, and will in many cases encourage it. Their attitude towards visitors photographing themselves with the skulls is less one of offense than it is amusement that outsiders find the encounter with these bones to be somehow shocking.

Which all comes back to the Trunyan attitude towards the dead. Even sympathetic Westerners don’t quite understand. There is love here and reverence, but the encounter does not violate a taboo. The cemetery ground returns the villagers to the elemental forces from which they came, but it does not extinguish them. The dead are still present, their spirits cradled by the magical banyan tree, and for the villagers the encounter with them is a natural and social one. As for the bones, yes they are important, but they are also a mere a symbol, left behind to remind visitors of the cycle of life and death.

All photographs by Paul Koudounaris

Paul Koudounaris is an author and photographer in Los Angeles. His PhD in Art History has taken him around the world to document charnel houses and ossuaries. His books of photography include The Empire of Death and Heavenly Bodies, which features the little known skeletons taken from the Roman Catacombs in the seventeenth century and decorated with jewels by teams of nuns. His other academic interests include Sicilian sex ghosts and demonically possessed cats.

March 16, 2017

Lead-Based Makeup Tutorial for Spring!

March 14, 2017

Faces of Death: Sarah Wambold

Tell us about your work, Sarah.

I am a licensed funeral director and embalmer in Austin, TX who works in green burial. My long-term project is called Conservation Burial, which works with state park agencies to establish green burial grounds adjacent to state parks as a way to protect the surrounding area from encroaching development. I’m pretty anti-establishment when it comes to funeral service; I’ve never been fully satisfied working in just a funeral home, nor have I ever been comfortable with the environmental damage of traditional burial. My current focus is on engaging more landowners to participate in this practice, so I do outreach at conservation workshops and events.

What are you working on this year?

Besides conservation burial, I am satisfying my creative tendencies by curating my first art show in Austin in August, called PopUp Mortuary. The idea is to explore the consumerism of the modern funeral industry with other artists and present some of the hidden aspects of the business to the public in an approachable way. I’m really interested in creating spaces for more death conversation. Stay tuned for more info!

What does death positivity mean to you?

Many things, but essentially normalizing the topic of death in everyday conversation.

What other death-related job that you don’t have, would you want?

Director of Education for a mortuary science program. We need complete education reform in this field and I have some ideas!

When you die, what do you want done with your corpse?

Natural burial all the way. Shroud optional.

Order members Landis Blair and Sarah Chavez with Sarah Wambold at the Death Salon Film Festival

Sarah has written two series for The Order, American Funeral Home Revolution and an interview series, Real American Death Heroes in which Sarah talks to people making compelling commentary on the death space in America.

She recently addressed What the Texas Fetal Remains Ruling Means and How You Can Take Action for Death & the Maiden and Sarah’s poignant piece At Rest in the Fields – Celebrating Childhood’s End at Eloise Woods for Texas Observer is a must-read.

To read more about Sarah and her work, check out her website or connect with her on Twitter and Instagram.

March 9, 2017

MY ANNOUNCEMENT

March 5, 2017

Mourning Mosa: My Cat’s Funeral in Japan

Mosa was not supposed to come into my life.

After my elderly lady cat, Brandy, died in my arms last April, I just wasn’t ready to have another furry little creature use my heart as a scratching post. The thought of opening myself up to another animal that WOULD DIE was more than I could consider handling for a while.

But then I flew back to Los Angeles for a wedding and while I was gone my husband found himself following a limping cat down a dark alley.

No, the cat did not sell him a fake Rolex. Instead, the black cat with piercing green eyes, an extra long body, and a teeny-tiny meow sold himself to my husband the sucker.

Between the two of us, I suppose it was only a matter of time. Suckers of a feather…

Upon closer inspection the black cat, whom we named Mosa or “tough guy” in Japanese, had huge, gnarly wounds on either side of his abdomen. It looked like a larger animal had picked him up and attempted to make a snack of him. Mosa had obviously fought his way free, with the battle scars to show for it, but he was in rough shape.

Afraid that Mosa would not last much longer in the soon-to-be-snowy Yamaguchi winter (did I mention I live in Japan?), my husband captured Mosa with the help of a local shop keeper who had been putting food out for him, and got him to a vet.

While Mosa got warmed up, stitched up, and filled with meds at the vet, my husband called me in Los Angeles to say, “So…I think we have a cat.” Despite my trepidation at having my cat-lady heart broken again, I was excited.

We had a cat for a whole two and a half weeks.

When I got back from Los Angeles we brought Mosa home from the vet and began the long process of healing his wounds and getting his immune system as strong as it could be. You see, while at the vet it was discovered that he had Feline Leukemia (FeLV), and while the vet was hopeful, Mosa’s on-and-off fever worried him. Though my husband and I knew that Mosa might be fighting a losing battle, we decided to dive in and give him the best life we could give him, for as long as possible.

From the moment Mosa perched on my lap and lapped tuna from my fingertips, I loved him.

Despite his dire situation, he revealed himself to be a rather chill, cheerful kitty. He was so much more chill than I’ll ever be.

Wrapped up in bandages for most of the two weeks he lived with us, he’d spend his days sauntering between our bed, his cushy dog-sized cat bed, and the fridge, where he would “meow” his gentlemanly but insistent tiny “meow” for food, several times a day.

He started to rapidly heal, he put on some weight, we dared to order him a cat condo for Christmas. But it was not meant to be.

One morning he stopped eating. By the afternoon he was lethargic and dazed. We rushed him to the vet where they gave him emergency intravenous medicines that seemed to stabilize him. But it wasn’t enough.

That night, curled up with my husband and me on the couch, he slipped away. It was so fast.

We held him and stroked him and mourned for all the adventures that might have been with our little “tough guy”. His fur had gotten so shiny, the wounds on his right side were almost completely healed and patches of skin were smooth and new. While I had known from the beginning that Mosa would likely have a short life with us, I didn’t think it would be this short.

Mosa’s last night in his bed.

Mosa stayed in his bed one more night, the cold and our home’s lack of insulation keeping his body cold until the morning. We decided to have Mosa cremated (burying him in our neighbor’s rice field seemed a wee bit gauche) so we called the only “pet funeral home” we could find in our rural town.

Within an hour, a smiley woman in a red wind breaker with the funeral home’s name in Japanese emblazoned on it, knocked on our front door. Bringing Mosa’s body to her, she reverently bowed to his corpse and gestured to a pink, cat-sized cardboard “coffin” in the back of her van.

I couldn’t help but think that it looked like something a creepy “Kid Sister” or “My Buddy” doll would come in, in the ‘80s.

The woman carefully tucked Mosa into his coffin with a pink blanket, leaving his head exposed, and handed me a plastic flower. I looked blankly at her. “For me?”

She pantomimed laying the flower on Mosa and turned expectantly to me. Feeling like this was like, “So not Mosa’s style” but wanting to be polite, I carefully laid the flower on Mosa and petted his head. Pleased, her smile increased and she bowed to me. And I bowed to her. And then my husband bowed too. There was a lot of bowing.

After filling out a form and paying about USD $100, the relentlessly smiley woman (“camp counselor” came to mind) looked up at the sky and said in Japanese, “Mmm, if it rains that’s a problem. We can’t cremate in the rain. We’ll call you. Plan on coming over at 11 o’clock.” She shut her van up, nodded her head at us, and drove off with our cat.

Tears rimming my eyes, the woman’s kindness and good intentioned professionalism having sparked another crying jag, I went back inside to get dressed for my cat’s cremation.

Within 15 minutes it was pouring rain and we got a phone call. It was the same woman telling us to come at two o’clock. For some reason cremation just couldn’t happen in the rain.

A few hours later, my husband and I pulled up in a taxi to the “pet funeral home.” It was a narrow, white, two story building in a residential neighborhood near downtown. If it wasn’t for the mobile cremation unit in the front yard, and the sleek, metal sign by the mailbox that said “pet funeral”, it would have been indistinguishable from the other upper middle class homes in the neighborhood. With its airy second-floor verandah, it looked like somewhere I’d like to go for a cocktail party.

It was still drizzling when we arrived, so uniformed attendants ran up to our taxi and covered us with umbrellas as we walked inside. A very Japanese touch. These workers were dressed in black and white, much closer to fancy valets or butlers than the camp counselor who picked up Mosa.

Inside, we found ourselves in a small room with white marble floors, two rows of white folding chairs in front of us, beyond that a TV screen with what looked like a PowerPoint slide of Mosa’s name in Japanese and English (Mosa Hung), and Mosa on a white table in a cat bed surrounded by real flowers. A woman in a long white skirt and a red vest asked us to walk forward and, “Spend some time with Mosa before we begin.”

Begin? Begin what?

I looked at my husband questioningly. Had something been lost in translation?

We had asked for the simplest, no-frills cremation possible. Some of the options included prayers, a ceremony, a blessing both before and after cremation – we wanted none of that. We knew the “viewing” of Mosa’s body was unavoidable at facilities such as these, and we appreciated their attempts to make Mosa’s funeral beautiful, but more than anything we just wanted to leave with a plain ceramic jar of Mosa’s cremated remains.

When we sat down after stroking Mosa’s body a bit (the flowers concealed ice packs), the woman came and stood by the TV and began reciting a roughly translated speech in English.

Again, I looked at my husband, eyes wide, and whispered, “Did we sign up for this?!”

She talked about how we were “gathered here today” to say goodbye to Mosa. How sad were to see him go, but how happy he made us, how lucky we were to “spend our days with him, our friend.”

Again I thought, “This is so not Mosa’s style.”

But as much as I wanted to just tune her out, ignore the canned sentiments she read off of a computer print out with the website printed across the top, I found myself softening to her, appreciating the attempt more than the execution. Though her words were stilted and a little awkward (Google translate is rarely the answer), I was moved by how seriously she took her job as “cat funeral eulogist”. She wasn’t phoning it in.

When an errant tear betrayed me and dropped from my eye along with a sniffle, she slowed and quieted her speech, looking right at me as she extolled Mosa’s virtues as a “best friend”. I got the feeling she really wanted to comfort me, to soothe me, and sincerity was her best tactic. Begrudgingly, I was moved.

While attending a funeral for my cat was the last thing I wanted to do that day, there I was, at a place devoted to the mourning of beloved pets, and I figured I could at least sip the Kool-Aid. Sip I did, and in spite of my determination to save my tears for later, I found myself a soggy, teary mess by the time the woman finished her speech.

Just the afternoon before, Mosa and I had sat by my living room window and watched the cranes land in the river behind our home. At this time yesterday he’d eaten a few last bites of tuna off my fingers. Though I’d sensed his life was coming to an end faster than I’d expected, I did not think I’d be cremating him the next day.

Mosa’s last day.

“But the joy, it cannot be taken away, Mosa, changes the life we had…”

The woman concluded her speech and asked us to take one last moment with Mosa. My husband and I knelt by his body, scratched his chin, touched his snaggletooth one last time. He really did look like he was sleeping.

We then chose to pick him up and deliver him to the mobile cremation unit outside. Loaded onto the back of what looked like a small, square Japanese truck, the unit looked like it could barely accommodate my six pound cat. What if someone had a labrador? I guess I understood why they didn’t want to cremate in the rain. The whole set-up looked slightly precarious and easily flooded.

The four women who ran the business – our red jacketed friend appeared again – stoically stood by with heads bowed as Mosa was delivered into the furnace.

Afterwards, my husband and I were ushered to the second floor of the building, where we were shown to what looked like a tiny Japanese living room with a white, rectangular dinner table. Sitting down with the woman who had delivered Mosa’s eulogy, she asked us how we were doing, if we wanted any food, and if we had any questions about Mosa’s cremation.

Assuring her that we were OK, weren’t hungry, and did not have any questions, she gestured to the coffee pot and cups by the door, and told us to make ourselves comfortable for the next hour and a half while Mosa was cremated and his remains placed in an urn.

Of course, it was at this point that I got overzealous with the coffee pot and poured near-boiling coffee all over my left hand, scalding it, and causing me to cry uncontrollably – not so much out of pain, but from the culmination of surprise, embarrassment, my dead cat, and OK fine, yes, pain.

The poor woman couldn’t stop apologizing and ran away to find me ice packs and wet cloths. I couldn’t help but wonder if the ice packs she brought me were the same ones that had kept Mosa chilly through his service. I hoped they were.

After being left alone for an hour (during which I not only mourned my cat, but also wondered if I had Johnny Tremain-ed my hand good and proper), the eulogy woman came in and asked if we’d like to inspect Mosa’s bones before they put them in an urn. If the skin hadn’t been peeling from my hand, I would have said yes, but at this point I just wanted to take Mosa’s remains, find some burn cream, and go home to cry over my dead cat and my dead epidermis in peace.

We went downstairs and Mosa’s remains were presented to us in a white and silver box that contained a plain, white ceramic container. Taking the lid off the container, I was delighted to see Mosa’s whole bone fragments, intact, and artfully arranged on top of his ashes. His remains were so beautiful; white bones speckled with black ash. I felt a surge of joy – “the joy, it cannot be taken away” – in getting to take my time with Mosa’s death.

From the moment we arrived at the funeral home, we had been encouraged to mourn, feel our feelings, and go slow. They had guided us in the best way they knew how, but really, it had been about what we needed as mourners. Cat funerals aside, there are few times in modern life that we get such freedom, such space and time.

As we climbed into the red jacketed woman’s van to go to a nearby pharmacist (Japan’s answer to walk-in clinics), I turned and thanked the assembled staff through a lump in my throat. They all smiled sweetly, micro-bowed, and the woman who gave the speech said, “Thank you for letting us share this beautiful day with you.”

And for the billionth time that day, I lost it. Not so much out of sadness, but out of surprise.

Like Mosa, everything about it had been unexpected, but it had been a beautiful day.

Louise Hung is an American writer living in Japan. You may remember her from xoJane’s Creepy Corner, Global Comment, or from one of her many articles on death, folklore, or cats floating around the Internet. Follow her on Twitter.

Caitlin Doughty's Blog

- Caitlin Doughty's profile

- 8408 followers