Caitlin Doughty's Blog, page 34

November 14, 2016

The Future of Women, Social Justice, and Death Acceptance

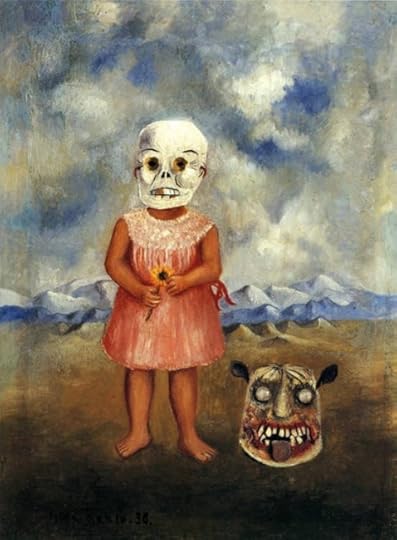

‘The Dead Girl’ Juan Soriano (1938)

Since I have mired in the slog of working on a new book, there has been nowhere near enough time to write as I should. But I’d like to alert you that there has been a ton of good work being shared and written over on the Order’s sister site, Death & the Maiden.

Death & the Maiden is run by the Order’s Executive Director, Sarah Chavez (Troop), and Lucy Coleman Talbot. It is a project to explore the cultural and historical roles women have played, and continue to play, in death.

I wanted to share with you a bit of what is happening there, from Sarah’s own words.

“Death & the Maiden offers a supportive and inclusive community which endeavors to amplify the voices of those actively creating the future of death.

We acknowledge that social justice movements fighting for human, social, or reproductive rights of women such as Black Lives Matter, Ni Una Mas and countless others, are streams of the death positive movement. Among our contributors are scholars, death doulas, scientists, morticians, game developers, museum professionals, artists, anthropologists and activists, to name a few.

In the press, women working with death are often reduced to stereotypes of the nurturing, sensitive, party planner – portrayed as selfless martyrs or even Disney Princesses – viewing the individuals, the work and the movement through a narrow lens, acknowledging only a fraction of the picture.

As women and non-binary folks, many of us are often forced to confront death in ways men are not. Murders of trans women of color, indigenous women in Canada, women in Mexico and El Salvador, or at the hands of our domestic partners and law enforcement are so common that they are now deemed “epidemics” by experts. Care of elderly and dying family members overwhelmingly falls to women, Latina teens and trans women have the highest rate of suicide attempts and deaths in the U.S., and of course, there is a long history of reproductive rights tied to death in countless ways.”

If you want your voice heard in this dialogue, please submit here. Sarah and Lucy will be posting some submissions on Death & the Maiden, and some here on The Order of the Good Death. We also have some larger projects in the works on these themes, so stay tuned.

‘Girl with Desk Mask’ by Frida Kahlo (1938)

Death & the Maiden will be holding their first conference in July of 2017. I will absolutely be there, and I hope you will consider adding your voice as well. Here is a call for papers (note: you do not have to be an academic– practitioners, innovators, activists and artists also welcome.)

In the past few days it has felt taxing for many to be a woman, a person of color, LGBT, the list goes on. But we have only just begun to fight, and our movement will only be made stronger as we seek to reveal the role death, and fear of death, plays in all our lives.

October 31, 2016

THE STAIN

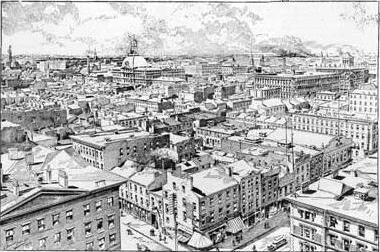

Danvers, MA, and Athens, OH

Towering above the local landscape on a hill in northeastern Massachusetts are the remains of the Danvers State Hospital, its imposing clock tower still looming over the traffic on nearby I 95.

Towering above the local landscape on a hill in northeastern Massachusetts are the remains of the Danvers State Hospital, its imposing clock tower still looming over the traffic on nearby I 95.

Here, it is said, John Hathorne—one of the head judges of the Salem witch trials, known for his harsh interrogations, his presumption of the guilt of the accused—built his home. In the curious way that America sometimes piles one tragedy upon another, as if to quarantine the evil, the land that had been Hathorne’s became the site of the Danvers State Hospital, a place built with the best of all possible intentions that would, in time, be known as the worst of all possible worlds.

The hospital was made famous by H. P. Lovecraft, who used it as a model for his fictional Arkham Sanitarium. The real-life hospital was built in 1874 and has long had a host of legends attached to it. Even after the hospital was closed in 1992, its legacy as a haunted asylum remains.

If you call to mind a haunted mental asylum, you are undoubtedly thinking of Danvers: an ornate but sinister Victorian façade, long wings, and, in the center of the building, a glowering clock tower. This is no accident; Danvers is one of many asylums based on a similar model, a design by architect Thomas Kirkbride that was first implemented in 1848, at the New Jersey State Lunatic Asylum in Trenton. By the end of the nineteenth century, Kirkbrides dotted the country, from Salem, Massachusetts, to Salem, Oregon—home of the Oregon State Insane Asylum (where Ken Kesey’s novel One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest was set). But within the past few decades, most of these buildings have been abandoned, demolished, or repurposed—few still operate as mental health institutions.

Danvers began shuttering its facilities in the late 1960s and shut down entirely in 1992. In 2006, after a lengthy process, a developer bought the property and set about renovating what was left of the asylum into luxury condos; the hospital’s massive wings were demolished, but the central administration building with its clock tower was preserved. Inside it smells of new carpet and fresh paint. If it feels eerie now, it’s perhaps not because of its provenance as a haunted asylum but because of its utter generic feeling: once you step inside its doors, you could be in any modest hotel chain in the country.

Unlike Moundsville and Eastern State, which were meant to exude a melancholy terror, their architecture part of the punishment, Danvers and its many sisters were designed to be welcoming, to reassure both patients and their families that they were in good, safe hands.

For centuries the mad belonged to the same group of society as the blind, the poor, the sick, and the elderly; all who could not work or otherwise easily contribute to society were more or less treated equally, regardless of the specificity of their situations. Prior to the rise of asylums, the mad were often sequestered in off-limits parts of their house. (Most famously, of course, in Jane Eyre, when Jane confronts the “madwoman in the attic,” Bertha.) But gradually, in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the first madhouses began offering a place where wealthy families could sequester relatives. The madhouse, in this light, was simply the attic, or the basement, of the house, made external and moved elsewhere.

Early madhouses were often revealed to be nightmares of abuse and neglect. Reports of incontinent patients hosed down with icy water, naked women chained haphazardly to the walls, fleas and rats rampant, and other horrors gradually prompted a desire for something more sanitary and humane. In England, Bethlehem Royal Hospital—more often known as Bedlam—became so associated with chaos, horror, and depravity that its name has entered the dictionary as a catchall for chaos and lunacy.

In 1843 Dorothea Dix emerged as a powerful voice calling for social reform. In a memorandum sent to the legislators of her home state of Massachusetts, she railed against “the present state of insane persons confined within this Commonwealth, in cages, closets, stalls, pens! Chained, naked, beaten with rods, and lashed into obedience!” She found instances of inmates padlocked in cellars, left in the dark to wail in torment for years without aid or treatment. Something had to give.

The “moral treatment,” as it came to be known, became the solution: rather than chained and forgotten, patients would be unshackled and allowed to move about the asylum at will. Instead of being tortured and imprisoned, patients would work and play. Through labor and sports, hobbies and other recreations, the moral treatment promised rehabilitation and freedom from insanity. The moral model was held out as a means of actually curing patients, rather than simply bundling them out of sight. “All experience,” Dix claimed, “showed that insanity reasonably treated is as curable as a cold or a fever.”

The Kirkbride asylum came to be the architectural style most thoroughly associated in the United States with the moral treatment. Rather than terrifying, the new asylum would be inviting, surrounded by lawns and gardens that patients could tend themselves. The defining features of the Kirkbride asylum include the central administration building, stately and elegant, with a central tower and elongated wings, forming a shallow V that extends back farther and farther. Part of the beauty of this architectural model was that wings could always be added farther out indefinitely. As a result, they were often massive, growing to hundreds of thousands of square feet.

There was another reason for the ostentation in the Kirkbride design: while insanity, in its various forms, has accompanied humankind forever, the discipline of psychiatry was still nascent, and the idea of “treating” mental patients was not yet fully accepted. Kirkbride believed that, unlike other diseases, mental illness could not be treated at home, and required an institutional setting, but at the same time treated their asylums as home: doctors referred to themselves as “fathers,” the asylum as “the house,” the patients as “the family.” The asylum provided a large and visible monument to psychiatry. Built with sturdy stone, designed with grace and care, it made real the role of the psychiatrist; like a badge or a uniform, the building itself established authority and legitimized the discipline. People could see and point to it as a place of healing; it allowed people to see insanity as a disease that could be cured, and a psychiatrist as the doctor to cure it. It also became a clearinghouse for all the various maladies that could now be grouped under the notion of mental health. The asylum, in its own way, created both the doctor and the patient.

Dozens of Kirkbride asylums were built throughout the country during the second half of the nineteenth century. They became a way for middle- and upper-class families to transfer care of sick relatives to private facilities where professionals could assume the burden of care. They were inseparable from the burgeoning industrialization of the day; academic Benjamin Reiss refers to the asylum as a “laboratory for the purification of culture and the production of useful citizens.”

The Kirkbride asylum was meant to be the antidote to the kinds of horrific treatments at places like Bedlam. Why are we so afraid of them today?

Kirkbride asylums are, by design, huge. Danvers was originally 70,000 square feet, but this is modest compared with some of her sisters. The Trans-Allegheny Lunatic Asylum of West Virginia was 242,000 square feet; the Northern Michigan Asylum in Traverse City was, when completed, more than 380,000 square feet; Greystone in New Jersey and the Ridges in Athens, Ohio, were both more than 660,000 square feet.

Originally the asylums’ size and amenities were subsidized by the affluent families who wanted the best for their relatives. But in the wake of the Civil War, veterans began to crowd the only federal Kirkbride asylum in Washington, DC (the Government Hospital for the Insane, since renamed St. Elizabeths Hospital), and it became clear that insanity was not simply a problem for those with money.

By the second half of the nineteenth century, psychiatric care fell more and more under state control. Private Kirkbride asylums were turned over to the states, and many states built their own in imitation of the same model. For the first time size and cost began to be an issue.

Public officials balked at lavishing taxpayer resources on so few inmates. One opponent, Hervey B. Wilbur, tallied up the cost of various asylums alongside their relative capacities: Danvers, built at a cost of $1.6 million, was designed to house only 450 patients; the Ridges, built for $950,000 for just 600 beds; Worcester State Hospital in Massachusetts, built for $1.25 million for only 450 beds; Greystone, built at a cost of $2.5 million for just 800 beds; and so on. Wilbur ultimately estimated that the Kirkbride asylums were costing around $2,600 per bed—and that excluded the site’s land value and its furniture, to say nothing of its staff and upkeep.

The solution seemed to be to take these great buildings and cram into them as many humans as possible. Buildings that were meant to be expansive and give patients a great amount of freedom were now stuffed with bodies, creating a downward spiral of deplorable conditions, under-staffing, overtaxed resources, and inhumane treatment.

Whatever the Kirkbride model promised by way of rehabilitation rates was effectively destroyed by this civic disengagement. The asylums became host to the worst kind of neglect and abuse that had typified their precursors—precisely what they had been designed to address.

By the end of the nineteenth century, the Kirkbride plan was being abandoned in favor of another form of architecture: the so-called cottage plan, which focused on campuses of smaller, freestanding buildings instead of giant, imposing façades. The Kirkbrides seemed anachronistic, reflective of an earlier age in which tax money was wasted on frivolous architectural details and massive floorplans.

In a short time the Kirkbride ideal went from being seen as progressive to being a symbol of neglect. And so the clock tower of the administration building became menacing and the loving touches meant to look like home became grotesque parodies.

Through it all the stately façade of the Kirkbride asylums remained stately, even if now the boastful architecture projected not sanity and sanitary conditions but a living nightmare. Stories of deaths inside the walls, bodies forgotten, “treatment” that resembled sadistic torture, gradually gave way to stories of ghosts, poisoned land, and haunted buildings.

The ghost stories surrounding the haunting of Kirkbride asylums, like the Danvers Hospital, often originate in a very real, very troubled past. Danvers quickly became notorious for its overcrowding, with almost four times as many patients as the hospital was designed to house. Patients sometimes died out of sight of the staff and their bodies decomposed for days before they were noticed. A report from 1939 noted that more than 10 percent of the asylum’s population had died within its walls. Add to the hospital’s grisly reputation the ignoble distinction of being the place where the prefrontal lobotomy was refined and widely implemented. It’s precisely this accumulation of horrors behind its walls that has led to the prevalence of spirits at Danvers and made it a mecca for paranormal enthusiasts. Thrill seekers trying to get access to the hospital even after it closed its doors led to heightened security on the property; more than 120 would-be ghost hunters have been arrested for trespassing since 2000.

Among those who claim to have seen things there is Jeralyn Levasseur, who grew up on the grounds (her father, Gerald Richards, was a hospital administrator). Levasseur recalls apparitions angrily scowling at her and her sister when she was a child, and once in high school her bedcovers were yanked off in the middle of the night without warning. Levasseur explained her experiences as a function of the changing nature of psychiatric health: “If you think back to the beginnings of medical science and the things done to people,” she told a local newspaper in 2003, “not because they thought they were doing bad, but because they were trying to do right, you have to wonder, did people think they were being tortured?”

The history of the asylum, as with the hospital, is the history of practices that once seemed necessary and now strike us as bizarre and troubling. Dr. Henry Cotton, who from 1907 to 1930 was the superintendent at the Trenton State Hospital (the former New Jersey State Lunatic Asylum, first of the Kirkbrides), performed savage surgeries on his patients for decades, extracting everything from teeth to stomachs in the belief that infections were contributing to his patients’ psychological instability.

Haunted by such legacies, the ruins of the Kirkbride asylums—and their attendant lore—reveal how uncomfortable we’ve become with antiquated methods of “healing the sick.” Whatever the intentions behind them, lobotomies, straitjackets, and aggressive shock therapy now strike us as barbaric and unnecessary and hover in the back of our collective consciousness. As a culture we still struggle with unresolvable questions that were once wrongly answered in places like these: Who is crazy? Are we crazy? And what can we do to assure ourselves that we aren’t?

The stories of ghosts in the asylums are mostly driven by this anxiety, and for the most part they are the standard, vague stories without much substantiation. But if there is a particularly haunting symbol of the fall of the Kirkbrides—one that is verifiably real—it can be found in Athens, Ohio, in what’s left of the Ridges.

The Ridges first opened in 1868 as the Athens Lunatic Asylum—a monstrous campus stretching more than eight hundred feet long. Rather than the single central tower of Danvers, the Ridges is marked by the dual towers of the main administration building, giving its profile vague echoes of Notre Dame.

The plan included not just decorative lakes and fields meant to soothe wandering intellects but also gardens, orchards, and eventually a dairy barn, all tended by the inmates, in an effort to make the facility entirely self-sufficient. For a time it even played host to an alligator, which lived in its fountain during the summer months.

The asylum was built to house just over five hundred patients, but the population quickly grew to double that; like other Kirkbrides, the site soon faced overcrowding. By the 1970s it was underfunded and ill managed, with inmates poorly accounted for and large portions of the complex boarded up or otherwise not in use. In such a setting emerged a ghost story so compelling it ended up in the Journal of Forensic Sciences—that of the ghost of Margaret Schilling.

A patient of the Ridges’ Continued Care Unit, Schilling, then fifty-three years old, had general freedom of movement and no serious behavioral problems—she was a model patient, her behavior unremarkable in every way. But on December 1, 1978, she failed to show up for dinner, having disappeared without any sign. Within a few hours an extensive search was launched, with staff crisscrossing the wards in search of her. They didn’t find her that night—a worrying sign, given the brutally cold winter that had set in.

It wasn’t until January 11, 1979, more than a month later, that workers found Schilling’s body in the attic of an abandoned wing. There was no sign of foul play. Schilling appeared to have taken off her clothes and folded them neatly before lying down to die on the cold floor. No one could say how long she’d been dead, but despite the cold winter, the room had been warm enough to allow for significant decay.

She left behind no clues as to how she’d ended up there or what had led to her death, but she did leave behind a gruesome mystery: when workers removed her decomposing corpse from the concrete floor, they found a stain in the shape of Schilling’s body: a ghostly outline in chalky white, ringed by a fainter, darker outline. And despite how hard workers tried to clean the floor, the stain would not come off.

The stain of Margaret Schilling still remains. Over the years it’s been the source of numerous ghost tales and rumors about the hospital, but Schilling’s manifestation is not paranormal. A forensic team that investigated the stain in 2007 determined that the image was likely a result of a process called adipocere: the breakdown during decomposition of the body’s fat into soap. The investigators found a waxy residue on the floor that had significantly altered the chemistry of the concrete itself, leaving it lighter than the surrounding area. While usually adipocere requires moist, enclosed conditions (say, those of a coffin buried in the right kind of soil), the forensic team’s best guess was that Schilling’s corpse had undergone some similar process despite the less-than-ideal conditions of the attic.

This strikes me as far more terrifying than an actual ghost. That this woman, placed in the asylum’s care, was left to rot on this floor, her body imprinting itself on the cold, unforgiving concrete, seems more disturbing than any tale of an apparition or unidentified noise. Herself unable to tell her tale, Margaret Schilling nonetheless managed to leave an indictment of her caretakers, a savage rebuke of the years of psychiatry that has left a deep stain on our history.

This regime of horrors wasn’t always evident. Family members and officials who came to tour these asylums often failed to see anything amiss. One of the benefits of the Kirkbride layout, with its gently flanking wings moving farther and farther away from the main administration building, was that it allowed the facility to segregate patients based on the severity of their condition. Traditionally the more difficult patients—the violent, the noisy, the untreatable—were housed in the wings farthest out, while the more sedate and promising patients were kept closer to the main building. Visiting relatives, shown the main building and the adjacent wings, left convinced that their relatives were in a stately, dignified place, not a madhouse. This was important, after all, so long as these institutions were private and depended on paying customers in the form of satisfied families. What went on behind closed doors would always remain a mystery.

This regime of horrors wasn’t always evident. Family members and officials who came to tour these asylums often failed to see anything amiss. One of the benefits of the Kirkbride layout, with its gently flanking wings moving farther and farther away from the main administration building, was that it allowed the facility to segregate patients based on the severity of their condition. Traditionally the more difficult patients—the violent, the noisy, the untreatable—were housed in the wings farthest out, while the more sedate and promising patients were kept closer to the main building. Visiting relatives, shown the main building and the adjacent wings, left convinced that their relatives were in a stately, dignified place, not a madhouse. This was important, after all, so long as these institutions were private and depended on paying customers in the form of satisfied families. What went on behind closed doors would always remain a mystery.

Stories began to emerge via the reports of those who’d escaped of horrors inside. Some of the more sensational of these came from a man named Ebenezer Haskell. Haskell was involuntarily committed to the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane in 1866 and escaped twice, the second time breaking his leg in the process. After a jury deemed him sane, Haskell wrote a book about his incarceration and trial in which he cited a number of horrific examples of patient mistreatment, including what he claimed was called the “Spread Eagle Cure,” a treatment that bore eerie similarities to the torture young Armstead Mason Newman endured in Lumpkin’s Jail:

A disorderly patient is stripped naked and thrown on his back, four men take hold of the limbs and stretch them out at right angles, then the doctor or some one of the attendants stands up on a chair or table and pours a number of buckets full of cold water on his face until life is nearly extinct, then the patient is removed to his dungeon cured of all diseases; the shock is so great it frequently produces death.

It’s hard to say for sure how accurate Haskell’s report was, particularly given his obvious axe to grind. But the lack of any clear information of what was going on, mixed with rumors and horror stories, only added to the picture the public began to form about the state of psychiatric care in general and at the asylum in particular.

The asylum in the nineteenth century embodies a tension between the visible and invisible—that is its most disturbing aspect. There is the highly visible and pronounced architecture, which projects one story, and there are the mostly invisible rooms on the edges, in the wings farthest out, hidden from public view.

Poe tapped into this tension in his short story “The System of Doctor Tarr and Professor Fether.” A visitor to an unidentified asylum in France (“a fantastic chateau, much dilapidated, and indeed scarcely tenantable through age and neglect,” one whose façade inspires the narrator with “absolute dread”) is shown a model of humane treatment, though gradually it becomes apparent that something is off. Only in the climax of the story is it revealed that the patients have overtaken the asylum; they’ve taken to impersonating the doctors, while the doctors themselves, along with the staff, have been locked up as patients. In the story’s final pages the doctors escape and riot; having been tarred and feathered, they unleash a terrifying fury on their captors, “fighting, stamping, scratching, and howling,” having been rendered less than human by their captivity. It’s a scene that speaks to the fine line between sanity and insanity. Once the doctors escape, they are as dangerous and as frightening as we’ve suspected the patients to be. Which is to say, once you’re inside the walls of the asylum, objective sanity is all but impossible.

Asylums became haunted by what happened inside their walls and also by the walls themselves: an architecture that was purposely boastful but which spoke of a previous generation with different ideals, economic motives, and attitudes toward the sick. The moment when we were most optimistic about our ability to cure the mind is when we built our most ostentatious palaces to psychiatry. There is a danger, then, in telegraphing too prominently one’s utopian ideals via architecture.

We design buildings not only for their utilitarian values but to project specific ideals and reflect our shared values. But these ideals and values are prone to change faster than the buildings. Shifting political fortunes, vacillating periods of excess and austerity, evolving attitudes about how the government should best serve its population—these all tend to move much faster than the time it takes for a building to outlive its usefulness.

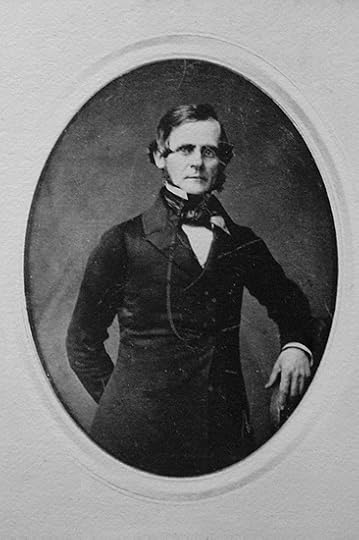

Thomas Kirkbride

“These are America’s castles,” Robert Kirkbride told me, speaking of the hospitals built on the plan of his ancestor Thomas Kirkbride. An architect and architectural historian himself, Robert was involved with the effort to save one building in particular: Greystone Park Psychiatric Hospital, in Morristown, New Jersey. Less than a year after it was closed, in 2008, a scheme to demolish the massive building and replace it with town houses was put forward by the city, only to be defeated by concerned citizens who argued that the hospital deserved saving: even as a gargantuan gothic ruin, Greystone was an important part of New Jersey’s history as well as a significant architectural landmark.

Cities have struggled to deal with these albatrosses—massive, unloved, associated with ghosts and an age gone by—as they’ve been decommissioned and treatment has moved elsewhere. Not only do they haunt our dreams; they haunt our local governments, who must figure out what to do with them. Many are on highly prized land that has developers salivating; even those that aren’t are massive buildings that require resources to keep them from falling into disrepair. They are filled with asbestos and lead paint—toxic materials that are another kind of civic ghost, a remnant of a former idea now discarded.

Danvers’s Kirkbride is a typical compromise, in which the most striking feature—the administration building’s façade—was preserved, while the surrounding structures were demolished. Others have been made into malls, universities, and other structures. The Northern Michigan Asylum, in Traverse City, was reopened in 2005 as the Village, a complex of shops, restaurants, and residences. The Hudson River Psychiatric Hospital, in Poughkeepsie, New York, after sustaining damage from a lightning strike and two subsequent fires, is likewise being reborn as a mixed-use commercial site. Also in New York, the Buffalo State Asylum for the Insane is in the process of being transformed into a hotel and conference center.

Other buildings have not fared as well. The city of Morristown solicited redevelopment bids for Greystone, but despite receiving six serious proposals from developers, it finally opted to spend $50 million to tear down the structure. Greystone, like a ghost, did not go quietly. Built with solid concrete, it cost the state more than thirty million dollars to knock it down.

Robert Kirkbride himself is haunted by a different aspect of these asylums: the very materials in their construction. The Northern Michigan Asylum, he points out, is a massive structure built entirely with a form of Michigan pine that has now vanished. Which is to say, these buildings carry another kind of history, another kind of legacy: the raw materials of our changing landscape, an archeology of our past.

The problem of the haunted Kirkbride asylums—behemoth structures that reflect a failed utopian plan, that have lingered long after they fell from vogue—is representative of many civic structures that we’ve come to see as haunted. Victims of changing fortunes, they’ve accrued stories of death, despair, and haunting in part because of their misuse or because the government and the people who built them were attempting to make a statement that no longer resonates in the same way. If the Kirkbride asylums are haunted, they are haunted, you could say, by the difference between how history is conceived and how it plays out.

October 24, 2016

ABRAHAM LINCOLN AND THE ST LOUIS VAMPIRE

The microfilm rooms at the libraries are filled with stories that captured the imagination of the nation for a few months, then vanished into the dustbins of history. Sometimes the supposed “strange events” were explained away and people lost interest. Sometimes there just stopped being anything new to say about a story and people moved on. Now and then a story will be go underground and re-emerge decades later with a life of its own and a whole new mythology surrounding it – for instance, everyone forgot about H.H. Holmes, the murderer in Devil in the White City, for decades, and when the story became famous again in the 21st century it now included several angles that had been thoroughly debunked in the 1890s, several bits that pulp writers had dreamed up in the 1940s, and some brand new outright fiction, as well. You see this pattern in a lot of crime, mystery, and paranormal tales.

But for every story that came back from underground, there are dozens that have yet to make a comeback, and seem like a missed opportunity for a perfectly good urban legend. Sometimes in the archives I’ll run into things that I can’t believe never returned to our national mythology. One of my favorites of these is the tale of Elizabeth Mund, the Vampire of St. Louis.

In 1864, as the civil war raged, St. Louis was a Union-controlled city in a Confederate state. Perhaps because of all the turmoil, and perhaps because it just wasn’t that big of a city yet, but local coverage in newspapers there was scarce compared to cities like New York or Chicago, where readers could pick from several papers. Some of the most detailed coverage available was in the Globe-Democrat, and even there local news was relegated to a couple of columns on page three. The rest was war news and advertisements.

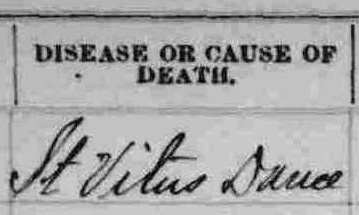

But like most 1860s papers, they always covered local hangings in exhaustive detail. And in 1864, every time there was a hanging at the prison, a young Swiss woman named Elizabeth Mund would appear wanting to suck the blood of the hanged man, believing it would cure her of a nerve disease.

Mund was twenty-three years old, a mother of three children, none of whom had survived infancy, was missing one eye, and was suffering from “the dancing heart,” which probably referred to St. Vitus’ Dance, a nerve disorder that causes a lot of twitching. It’s not a fatal disease, and usually goes away on it’s own after a while, and isn’t really even one of those diseases where the cures of the day were worse than the ailment (most of the remedies I could find were of the “take a cold shower and watch your diet” variety). Given her affliction and her recent history, it’s hard not to be sympathetic to Elizabeth, but it’s also easy to imagine her straining the bounds of your sympathy. It’s one thing to feel sorry for a person, and quite another for her to ask you to help her drink your recently-executed husband’s blood.

Mund was twenty-three years old, a mother of three children, none of whom had survived infancy, was missing one eye, and was suffering from “the dancing heart,” which probably referred to St. Vitus’ Dance, a nerve disorder that causes a lot of twitching. It’s not a fatal disease, and usually goes away on it’s own after a while, and isn’t really even one of those diseases where the cures of the day were worse than the ailment (most of the remedies I could find were of the “take a cold shower and watch your diet” variety). Given her affliction and her recent history, it’s hard not to be sympathetic to Elizabeth, but it’s also easy to imagine her straining the bounds of your sympathy. It’s one thing to feel sorry for a person, and quite another for her to ask you to help her drink your recently-executed husband’s blood.

On March 19, 1864, the Globe-Democrat broke her story with an article so wild that several papers around the country excerted it: “A Female Vampire – A Woman Wants to Suck the Blood of a Man Who Has Been Hung.”

Captain Bishop, the jailer, told the Globe Democrat that Elizabeth came into his office smiling and asking if it was true that a man named John Abshire, sentenced by court martial to be hanged. A friend of hers had apparently told her that her disease could be cured by wearing a bit of rope that had been used to hang a man around her neck, and Elizabeth, perhaps combining another old-world superstition and perhaps just deciding to take things even further, wanted to suck the hanged man’s blood.

Amused, Captain Bishop had to be the bearer of bad news (for her): Abshire’s sentence had been commuted. But he cheered her back up by telling her that another hanging was scheduled for the next month, in which a man would be hanged until he was “dead, dead, dead,” and that the jail physician would get her some of the blood.

Sure enough, on April 15, a murderer named Valentine Hansen was scheduled to be hanged. And Elizabeth Mund arrived at the jail, where she met with Mrs. Hansen, whom the press had taken to calling “the little woman in black.” Mrs. Hansen, naturally, was not amused by Elizabeth’s request. “The little woman in black indignantly spurned the blood-sucker,” the Globe-Democrat wrote, “and our informant says there was quite a war of words between the two women. The Vampire took her departure, and mingled with the crowd on the outside of the enclosure…she waited on the street with the feverish hope that her desire might be gratified.”

After the execution, the reporters found Elizabeth hanging around by the gates. “Her was was pale and cadaverous, her baleful blue eye (she has lost the sight of one eye) had the look of a hyena’s, and her lips protruded as if preparing to suck the blood from a man’s jugular vein. We questioned the vampire but could get no intelligible answer from her. She was watching the ponderous iron door of the jail, as if expecting to see the body of the murderer brought forth. Whether she succeeded in obtaining a portion of Hansen’s blood, we did not stay to see.”

It’s to be assumed that Mund was unsuccessful, because she showed up at another execution in August, when one William Jackson Livingston was hanged as a spy. “At an early hour,” the paper wrote, “the jail was visited by the inevitable Elizabeth Mund… she implored Marshall Coff, with tears in her eye (she has but one) to allow her to enter the jailyard and obtain a few drops of Livingston’s blood. The marshall, remembering her violent demonstrations at the execution of Hansen, told her she would be allowed to come in at twelve o’clock, when she could get as much blood as she wanted.”

This, however, was Marshall being tricky: the hanging was actually taking place at ten, and by noon the body was long gone.

How Mund reacted to the trick (or the paper’s snark about her missing eye) wasn’t recorded; the Globe said only that she’d left disappointed for the fifth or sixth time. Whether she’d really been at that many executions is hard to determine; lists of executions in Missouri that have been published over the years tend to be inaccurate and incomplete. The hangings of Abshire, Hansen and Livingston are the only ones I could find at which Mund was mentioned. And this seems to have been her last attempt; when two “bushwackers” were hanged a few weeks after Livingston, the Globe didn’t mention Mund at all, though they reported that around two thousand people crowded around the jail, climbing hills and trees to get a view.

Abraham Lincoln to William S. Rosecrans

Little can be found about Mund besides these handful of mentions; it’s quite possible that she simply got better and stopped bothering. It’s tempting to imagine that today every news outlet would have hounded her for more information: we’d critique every line she’d ever posted on social media, and we’d get updates on her activities every time an execution came up for years. But papers of 1864 were content to let her slink into obscurity, having suffered no greater indignity than a couple of cruel remarks about missing an eye (which was pretty lousy of the reporters, but considering that she was rooting for people to be executed and had the nerve to ask a widow-to-be for some of her husband’s blood, it could have been worse). Historically it’s tempting to wish that there was more data, but probably better that she was left alone.

Another person or two has seen one of the articles about her excerpted in digitized papers from 1864 and mentioned it, but there’s one aspect to her story that’s been forgotten, and really shouldn’t have been: the person who commuted Abshire’s sentence was none other than President Abraham Lincoln.

He probably never knew it, but in commuting the sentence, Lincoln had thwarted the efforts of a real life vampire.

So there was a kernel of truth in Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter, after all. Who knew?

ADAM SELZER is a Chicago rideshare driver and and tour guide who writes mysteries and true crime books. He recent works include Mysterious Chicago and Just Kill Me, a novel about a ghost tour guide who makes places more haunted by killing people at them. His massive HH Holmes: The True Story of the White City Devil will be released in April. See him online at adamchicago.com

October 14, 2016

ASK A MORTICIAN – Open Eye Wakes & Body Farms

September 29, 2016

REST IN PEACE, CONFEDERATE CAMEL

September 2, 2016

CALENDAR OF EVENTS – FALL 2016

Death Salon, September 16-18th, Houston – SOLD OUT

Save the Date! Los Angeles evening event with Order member Colin Dickey, on October 12th, details TBA

Living the Good Death, hosted by the Springfield-Greene County Library District, October 15th, Springfield, MO.

TED x Vienna, October 22nd in Vienna.

Cleveland Memorial Society Annual Meeting, November 13th, Cleveland.

SciComm Camp, November 18-2oth, Malibu.

TEDMED, November 30th – December 2nd, Palm Springs.

UNDERTAKING LA

SAVE THE DATE! Undertaking LA morticians Caitlin Doughty and Amber Carvaly will be hosting their first workshop on November 20th at CFI in Los Angeles. If you are interested in attending please sign up for the Undertaking LA mailing list by following the instructions outlined here. Further details TBA.

DEATH SALON

Our next Death Salon will take place in Houston on September 16-18th, in partnership with the Aurora Picture Show! This will be our very first Death Salon Film Festival – This event is currently SOLD OUT.

ORDER OF THE GOOD DEATH MEMBERS

Caitlin Doughty, Dr. Paul Koundounaris, Jae Rhim Lee, Megan Rosenbloom, Sarah Troop and Sarah Wambold will all be appearing at Death Salon, September 16-18th, Houston. SOLD OUT.

Caitlin Doughty, Dr. Paul Koundounaris, Jae Rhim Lee, Megan Rosenbloom, Sarah Troop and Sarah Wambold will all be appearing at Death Salon, September 16-18th, Houston. SOLD OUT.

Jae Rhim Lee is teaming up with Ace Hotel in New York for Natural Causes, September 8th-30h.

Dr. John Troyer and Carla Valentine will be presenting at Immortal Passion: Necrophilia and the Penetration Paradox on October 9th in London.

Dr. Judy Melinek will be speaking at the Wisconsin Coroners & Medical Examiners’ Association Conference on October 24th in Neenah, WI.

Colin Dickey will be on tour promoting his upcoming book, Ghostland. Check here, for dates and locations.

Sarah Wambold will be on hand to host a lecture by Dr. Paul Koundounaris, Ship Cats: Adventure! Courage! Betrayal! on September 14th in Austin.

DEATH SPACES RUN BY ORDER OF THE GOOD DEATH MEMBERS

The following institutions are run by members of The Order and offer a full calendar year of death positive events that are open to the public.

The Body Appropriate, located in San Francisco, is run by Order Member Stephanie Stewart-Bailey. The Body Appropriate often features Sound Public Dissections, Visceral Cinema and more. Check the out the entire schedule here.

The Body Appropriate, located in San Francisco, is run by Order Member Stephanie Stewart-Bailey. The Body Appropriate often features Sound Public Dissections, Visceral Cinema and more. Check the out the entire schedule here.

Join Barts Pathology Museum’s Technical Curator, Carla Valentine for an incredible array of events inside a stunning Victorian pathology museum in London. Taxidermy classes, potting workshops and an array of fascinating lectures await you. Check the official calendar of events here.

Join Barts Pathology Museum’s Technical Curator, Carla Valentine for an incredible array of events inside a stunning Victorian pathology museum in London. Taxidermy classes, potting workshops and an array of fascinating lectures await you. Check the official calendar of events here.

Joanna Ebenstein’s incomparable Morbid Anatomy Museum in Brooklyn should be on every Deathling’s bucket list. In addition to visiting the museum you can catch any number of workshops, field trips, lectures and unique events. Visit their website for a full listing.

Joanna Ebenstein’s incomparable Morbid Anatomy Museum in Brooklyn should be on every Deathling’s bucket list. In addition to visiting the museum you can catch any number of workshops, field trips, lectures and unique events. Visit their website for a full listing.

OTHER DEATH POSITIVE EVENTS

Securing the Shadow: Posthumous Portraiture in America, an exhibition dedicated to an examination of American self-taught portraiture of the 18th and 19th centuries through the lens of memory and loss. October 2016 – February 2017, NYC.

The Last Tuesday Society always has something fabulous going on. This month features seances, taxidermy classes and plenty of deathy lectures including Death and the Maiden, and a look at the history of witches’ ointments. Ongoing, London.

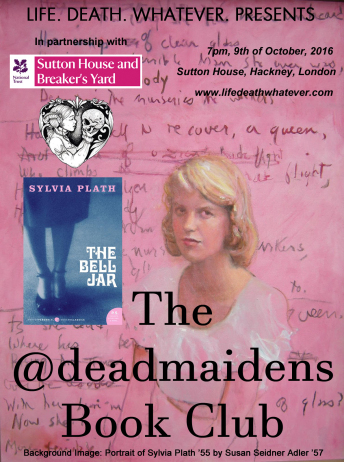

Death & the Maiden Book Club hosted by death positive website, Death and the Maiden, co-founded by The Order’s own Sarah Troop, D&tM will be launching a book club, led by co-founder Lucy Talbot. October 9th, London.

Death & the Maiden Book Club hosted by death positive website, Death and the Maiden, co-founded by The Order’s own Sarah Troop, D&tM will be launching a book club, led by co-founder Lucy Talbot. October 9th, London.

43rd Annual Dia de Los Muertos Celebration at Self Help Graphics is believed to be the oldest day of the dead commemoration in the U.S. November 2nd, Los Angeles.

Death and Dying Series hosted by the Springfield-Greene County Library is hosting a plethora of death related book clubs, events, death authors and discussion groups on everything from suicide to talking to children about death. Full listing here. Ongoing, Springfield, MO.

London Month of the Dead is making all of our death dreams come true with their outstanding month-long series of events and experiences. October, London.

Mourning Tours at the Heritage Square Museum. Learn all about death and mourning etiquette during the Victorian era, the movement of Spiritualism, and how other cultures celebrate and remember their dead. October 22nd, & 23rd, Los Angeles.

Into the Veil, join Atlas Obscura and Laurel Hill Cemetery for an immersive evening as they explore the liminal world that exists between the land of the living and the realm of the dead. September 10th, Philadelphia

Life. Death. Whatever. hosts weekly events at Sutton House, including Funeral Tuesdays. Ongoing, London.

Kicking the Bucket: A Festival of Living and Dying has a full line-up of events including home funeral workshops, lectures on assisted dying issues, musical and theatrical performances and much more. October and November, various locations near Oxford.

August 11, 2016

DAD IS DEAD! TELL THE BEES!

July 27, 2016

Death and Broken Cups

“As soon as the grave is filled in, acorns should be planted over it, so that new trees will grow out of it later, and the wood will be as thick as it was before. All traces of my grave shall vanish from the face of the earth, as I flatter myself that my memory will vanish from the minds of men.”

This passage from the will of the Marquis de Sade has always struck a chord with me. Of course, he penned it as his last raging, disdainful grimace at mankind, but the very same thought can also be peaceful.

I have always been sensitive to the poetic, somewhat romantic fantasy of the taoist or buddhist monk retiring on his pretty little mountain, alone, to get ready for death. In my younger days, I thought dying meant leaving the world behind, and that it carried no responsibility. In fact, it was supposed to finally free me of all responsibility. My death belonged only to me.

An intimate, sacred, wondrous experience I would try my best to face with curiosity.

Impermanence? Vanishing “from the minds of men”? Who cares. If my ego is transient like everything else, that’s actually no big deal. Let me go, people, once and for all.

In my mind, the important thing was focusing on my own death. To train. To prepare.

“I want my death to be delicate, quiet, discreet”, I would write in my diary.

“I’d prefer to walk away tiptoe, as not to disturb anyone. Without leaving any trace of my passage”.

Unfortunately, I am now well aware it won’t happen this way, and I shall be denied the sweet comfort of being swiftly forgotten.

I have spent most of my time domesticating death – inviting it into my home, making friends with it, understanding it – and now I find the only thing I truly fear about my own demise is the heartbreak it will inevitably cause. It’s the other side of loving and being loved: death will hurt, it will come at the cost of wounding and scarring the people I cherish the most.

Dying is never just a private thing, it’s about others.

And you can feel comfortable, ready, at peace, but to look for a “good” death means to help your loved ones prepare too. If only there was a simple way.

The thing is, we all endure many little deaths.

Places can die: we come back to the playground we used to run around as kids, and now it’s gone, swallowed up by a hideous gas station.

The melancholy of not being allowed to kiss for the first time once again.

We’ve ached for the death of our dreams, of our relationships, of our own youth, of the exciting time when every evening out with our best friends felt like a new adventure. All these things are gone forever.

And we have experienced even smaller deaths, like our favorite mug tumbling to the floor one day, and breaking into pieces.

It’s the same feeling every time, as if something was irremediably lost. We look at the fragments of the broken mug, and we know that even if we tried to glue them together, it wouldn’t be the same cup anymore. We can still see its image in our mind, remember what it was like, but know it will never be whole again.

I have sometimes come across the idea that when you lose someone, the pain can never go away; but if you learn to accept it you can still go on living. That’s not enough, though.

I think we need to embrace grief, rather than just accepting it, we need to make it valuable. It sounds weird, because pain is a new taboo, and we live in a world that keeps on telling us that suffering has no value. We’re always devising painkillers for any kind of aching. But sorrow is the other side of love, and it shapes us, defines us and makes us unique.

For centuries in Japan potters have been taking broken bowls and cups, just like our fallen mug, and mending them with lacquer and powdered gold, a technique called kintsugi. When the object is reassembled, the golden cracks – forming such a singular decoration, impossible to duplicate – become its real quality. Scars transform a common bowl into a treasure.

I would like my death to be delicate, quiet, discreet. I would prefer to walk away on tiptoe, as not to disturb anyone, and tell my dear ones: Don’t be afraid. You think the cup is broken, but sorrow is the other side of love, it proves that you have loved. It is a golden lacquer which can be used to put the pieces together.

Here, look at this splinter: this is that winter night we spent playing the blues before the fireplace, snow outside the window and mulled wine in our glasses.

Take this other one: this is when I told you I’d decided to quit my job, and you said go ahead, I’m on your side.

This piece is when you were depressed, and I dragged you out and took you down to the beach to see the eclipse.

This piece is when I told you I was in love with you.

We all have a kintsugi heart.

Grief is affection, we can use it to keep the splinters together, and turn them into a jewel. Even more beautiful than before.

As Tom Waits put it, “All that you’ve loved, is all you own”.

Ivan Cenzi is an explorer of the uncanny and collector of curiosities. Since 2009 he has been curator of Bizzarro Bazar, a blog dedicated to all things strange, macabre and wonderful.

July 21, 2016

Ask A Mortician – CLOSING MOUTHS POSTMORTEM

July 14, 2016

EASY STEPS to becoming an Alternative Mortician!

Caitlin Doughty's Blog

- Caitlin Doughty's profile

- 8410 followers