Caitlin Doughty's Blog, page 36

April 5, 2016

DEATH & FEMINISM

March 16, 2016

MORBID MINUTE – Decomposed Whale Cure

March 9, 2016

The Unpleasant Duty: An Introduction to Postmortem Photography

“Place the body on a lounge or sofa, have the friends dress the head and shoulders as near as in life as possible, then politely request them to leave the room to you and aids, that you may not feel the embarrassment incumbent should they witness some little mishap liable to befall the occasion.” Since the inception of photography in the first half of the 19th century, photographing the dead has been an accepted memorial practice. Although it is often cast aside or scoffed at as some kind of bizarre and morbid happening, postmortem photographs represent a particular part of mourning in this era. These beautiful and moving images depict the last moment that a family would be able to grieve with their deceased loved one present. Beyond this, postmortem photographs speak to the mourning and funeral norms of the times.

The memorial, or postmortem photograph, has been around nearly as long as photography itself. The first photograph of a deceased person was a daguerreotype. This antiquated photographic process is understood as one of the first types of photography, which renders a ghostly image on a metallic, silvery surface. Developed in 1839, the first postmortem photograph was taken in 1841. This timeline shows that photography was actually filling a kind of memorial void that other forms, such as paintings, could not. Most importantly, taking a photograph of your dead loved one was simply faster than other mediums, and would eventually become more affordable as well. It was also possible that these photographs were the only images captured of this person, as photography was still a recent invention that was not always affordable or available. This final image may also be the only documentation of this person in their entire life.

The practice of capturing a final “likeness” had even become part of the photographer’s professional repertoire. In an 1869 edition of the Philadelphia Photographer, a trade journal offering a vast catalog of information and contacts, a photographer describes this experience. J.M. Houghton begins, “The other day I was called upon to make a negative of a corpse,” who then goes on to discuss the moving of the body closer to a window, in order to make use of natural light: “I selected a room where the sunlight could be admitted, and placed the subject near the window, and a white reflecting screen on the shade side of the face.” This standard practice, photographing the dead, was even worth discussing amongst professionals. Since the body would be moved by the photographer and was obviously less mobile, there were certain tips and tricks that made image-making much more efficient.

The practice of capturing a final “likeness” had even become part of the photographer’s professional repertoire. In an 1869 edition of the Philadelphia Photographer, a trade journal offering a vast catalog of information and contacts, a photographer describes this experience. J.M. Houghton begins, “The other day I was called upon to make a negative of a corpse,” who then goes on to discuss the moving of the body closer to a window, in order to make use of natural light: “I selected a room where the sunlight could be admitted, and placed the subject near the window, and a white reflecting screen on the shade side of the face.” This standard practice, photographing the dead, was even worth discussing amongst professionals. Since the body would be moved by the photographer and was obviously less mobile, there were certain tips and tricks that made image-making much more efficient.

Charlie E. Orr, a photographer from Sandwich, Illinois, wrote into the Philadelphia Photographer in January of 1873, and wrote a brief article to “afford assistance to some photographer of less experience, to whom it might befall the unpleasant duty to take the picture of a corpse.” Orr goes on to explain:

Place you camera in front of the body at the foot of the lounge, get your plate ready, and then comes the most important part of the operation (opening the eyes); this you can effect handily by using the handle of a teaspoon; put the lower lids down, they will stay; but the upper lids must be pushed far enough up, so that they will stay open to about the natural width, turn the eyeball round to its proper place, and you have the face nearly as natural as life. Proper retouching should remove the blank expression and stare of the eyes.

Photographing the dead proved to have some interesting challenging, but unlike the living, the deceased sitter could not move. With long exposure times, the dead were the ideal photographic subject.

The composition and appearance of postmortem photographs changed throughout the 19th century. For example, postmortem photographs taken prior to the 1860s depict death as if it had just happened; many images from this era share similar poses and details. Most of these photographs concentrate on just the face or head, laid out on furniture in the home or placed on a bed or in a child’s buggy. With many photographs showing the body laid out, sometimes on a bed, the viewer is invited to understand the death as a visual representation of the “last sleep.” These photographs were not intended to dupe the viewer into assuming the deceased was still alive but rather they would be posed in such a way that to recall or depict the subject as if they were just asleep, thus softening the sad reality that they had died. In this way, the postmortem photograph represents the body at peace.

Around the turn of the mid 19th century, postmortem photographs also demonstrate shifting cultural ideas. At this point, many postmortem photographs depicted children. Throughout the Industrial Revolution, children were valued laborers. It was not until 1836 that Massachusetts became the first state to sign child labor legislation into law; it required that children under the age of fifteen attend school for at least three months out of the year. This law also speaks to the fairly recent inception of systematized formal education for children. With newly enacted child labor laws in conjunction with the increasing value placed on formal education, children began to occupy a different role within the family. They became understood not only as wage earners, but as young, evolving humans who should be nurtured and supported.

Around the turn of the mid 19th century, postmortem photographs also demonstrate shifting cultural ideas. At this point, many postmortem photographs depicted children. Throughout the Industrial Revolution, children were valued laborers. It was not until 1836 that Massachusetts became the first state to sign child labor legislation into law; it required that children under the age of fifteen attend school for at least three months out of the year. This law also speaks to the fairly recent inception of systematized formal education for children. With newly enacted child labor laws in conjunction with the increasing value placed on formal education, children began to occupy a different role within the family. They became understood not only as wage earners, but as young, evolving humans who should be nurtured and supported.

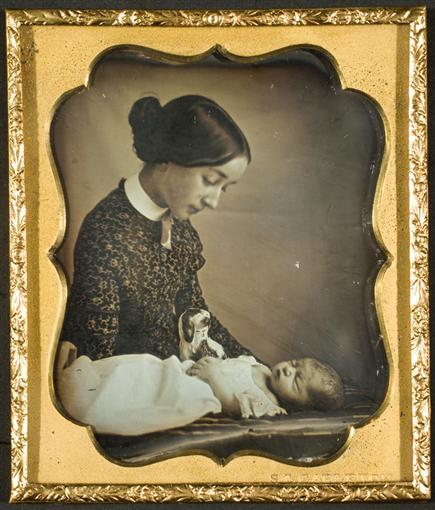

With this changing role, postmortem photographs of children also began to change. For example, this photograph from 1860 depicts a recently deceased young girl, who is sitting on the lap of her mourning mother. The mother’s face is straight and unwavering, looking directly at the camera. She holds her daughters hand for the last time, as her small body is cradled by her mothers. Her mother is clearly in mourning. Many photographs of this decade began to include the presence of loved ones, either around the body of the recently deceased, or embracing or touching them in some way.

With this changing role, postmortem photographs of children also began to change. For example, this photograph from 1860 depicts a recently deceased young girl, who is sitting on the lap of her mourning mother. The mother’s face is straight and unwavering, looking directly at the camera. She holds her daughters hand for the last time, as her small body is cradled by her mothers. Her mother is clearly in mourning. Many photographs of this decade began to include the presence of loved ones, either around the body of the recently deceased, or embracing or touching them in some way.

At this time, many photographs of the dead became more elaborate or indicative of what that person had been like in life. Some children would be photographed with a favorite toy or blanket, depicting an image that allows the viewer to imagine what they had been like in life. Other photographs would show a body outstretched in their final resting place, which may be an elaborate coffin or even a casket.

By the end of the 19th century and the start of the 20th century, funerary patterns began to shift. Embalming was first introduced on a national level and seen widely after President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination on April 15, 1865. He laid in state for three days and was viewed by over 25,000 mourners before being sent to his home of Springfield, Illinois: his body traveled over 1,700 miles from Washington D.C. to his hometown, where he was to be buried, making many stops along the way. Embalming required professional intervention in the funeral, which led to the inception of the funeral director.

By the end of the 19th century and the start of the 20th century, funerary patterns began to shift. Embalming was first introduced on a national level and seen widely after President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination on April 15, 1865. He laid in state for three days and was viewed by over 25,000 mourners before being sent to his home of Springfield, Illinois: his body traveled over 1,700 miles from Washington D.C. to his hometown, where he was to be buried, making many stops along the way. Embalming required professional intervention in the funeral, which led to the inception of the funeral director.

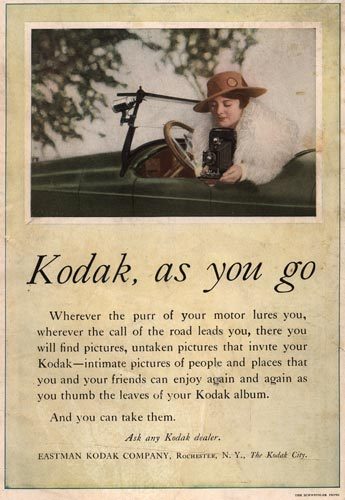

Photography was also becoming a daily part of American life. Photographic technology became easier to use, and the supplies became more accessible. Companies like Kodak began to advertise heavily, creating campaigns that would heavily influence how photographs were taken up in culture. Photos were now taken at holidays and on vacation, as well in day to day activities. When photos were able to depict the joys of life, there was less emphasis on photographing the dead. There was simply other ways to show someones life other than their last moments.

Photography was also becoming a daily part of American life. Photographic technology became easier to use, and the supplies became more accessible. Companies like Kodak began to advertise heavily, creating campaigns that would heavily influence how photographs were taken up in culture. Photos were now taken at holidays and on vacation, as well in day to day activities. When photos were able to depict the joys of life, there was less emphasis on photographing the dead. There was simply other ways to show someones life other than their last moments.

Postmortem photographs became less popular in the first quarter of the 20th century. Infant mortality dropped due to a variety of important medical developments, and childhood illnesses began to be better managed. Photography captured the living, and less of the dead. Shifting away from Victorian ideals surrounding death, dying became medicalized and professionalized.

Although postmortem photography did not simply stop, it lost the popularity it once had many years prior. Photographing the dead still happens today, but not to the extent that it once had. These kinds of photographs end up on ebay and in thrift stores, often separated from the families that they once belonged to. For many that do photograph at funerals, digital photos end up on computers or phones, ready to be deleted when the longing to look has passed. What has not changed, however, is our desire to look at photos of those we loved, whether they are dead or alive.

IMAGE: http://www.loc.gov/item/2009633711/

Drew Gilpin Faust. This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War. (New York: Random House, 2008), 157.

IMAGE: https://tpwd.texas.gov/spdest/findade...

Jay Ruby. Secure the Shadow: Death and Photography in America. (Boston: MIT Press, 1995), 19.

Child Labor Public Education Project. “Child Labor in U.S. History.” University of Iowa Labor Center and Center for Human Rights. http://www.continuetolearn.uiowa.edu/laborctr/child_labor/

IMAGE: http://www.loc.gov/resource/ppmsca.34974/

IMAGE: http://www.loc.gov/resource/ppmsca.11042/

Philadelphia Photographer. 1875 volume 11. Page 27.

John Hannavy ed. Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography. (New York: Routledge, 2008), s.v. “postmortem photography.”

Philadelphia Photographer. 1869 volume 6. Page 241.

Philadelphia Photographer. 1873 volume 10. Page 200.

The Unpleasant Duty: An Introduction to Postmortem Photography

March 3, 2016

Calendar Of Events – Spring 2016

University of Indiana’s conference Death, Dying, and the Undead:

(Re)Conceptualizing Death and Religion, Keynote Speaker, on April 8th.

DEATH SALON

Save the Date! Our next Death Salon will take place in Houston on September 17, 2016 in partnership with the Aurora Picture Show! This will be our very first Death Salon Film Festival – submissions are currently open. Please visit the Death Salon website for details and be sure to sign up for the mailing list.

ORDER OF THE GOOD DEATH MEMBERS

Dr. John Troyer will be speaking about Spectacular Dead Taxidermy, on March 3rd, at the Bristol Museum. Dr. Troyer will also be speaking at Encountering Corpses II on March 19th in Manchester, UK.

Katrina Spade will be a speaker at Life After Death: TEXxOrcas Island, on March 5th, Orcas Island, WA. Katrina will also e speaking at Nature Does Death Better, on March 12th in Kamloops, BC.

Carla Valentine will be speaking at Encountering Corpses II on March 19th in Manchester, UK.

Rachel James’ latest project, Posey Filled Pockets is hosting a variety of monthly events in Grass Valley, CA. First up, A Lovely Corpse. Dates and details right here.

Sarah Troop will be leading a tour of Forest Lawn, on April 30, in Glendale, CA. Details TBA.

DEATH SPACES RUN BY ORDER OF THE GOOD DEATH MEMBERS

The following institutions are run by members of the Order and offer a full calendar year of death positive events that are open to the public.

The Body Appropriate, located in San Francisco, is run by Order Member Stephanie Stewart-Bailey. The Body Appropriate often features Sound Public Dissections, Visceral Cinema and more. Check the out the entire schedule here.

The Body Appropriate, located in San Francisco, is run by Order Member Stephanie Stewart-Bailey. The Body Appropriate often features Sound Public Dissections, Visceral Cinema and more. Check the out the entire schedule here.

Join Technical Curator, Carla Valentine for an incredible array of events inside a stunning Victorian pathology museum in London. Throughout the upcoming season you can learn how to pot your own heart or explore the Chinese custom of footbinding. See these and so much more on the Barts Pathology Museum event page.

Join Technical Curator, Carla Valentine for an incredible array of events inside a stunning Victorian pathology museum in London. Throughout the upcoming season you can learn how to pot your own heart or explore the Chinese custom of footbinding. See these and so much more on the Barts Pathology Museum event page.

Joanna Ebenstein’s incomparable Morbid Anatomy Museum in Brooklyn should be on every Deathling’s bucket list. In addition to visiting the museum you can catch any number of workshops, field trips, lectures and unique events. Coming up this season you can attend a taxidermy class, a Victorian Hair Art workshop or an illustrated lecture on body horror in Japanese animation, to name just a few. Visit their website for a full listing.

Joanna Ebenstein’s incomparable Morbid Anatomy Museum in Brooklyn should be on every Deathling’s bucket list. In addition to visiting the museum you can catch any number of workshops, field trips, lectures and unique events. Coming up this season you can attend a taxidermy class, a Victorian Hair Art workshop or an illustrated lecture on body horror in Japanese animation, to name just a few. Visit their website for a full listing.

OTHER DEATH POSITIVE EVENTS

Death: The Human Experience is an art exhibit that explores the human response to death through hundreds of objects and stories from across the world, from ancient times to modern day. Don’t miss the museum’s Death Fair on March 5th – a day of talks, walks, demos and stalls offering a practical guide to dealing with death, dying and bereavement.

Flat Death, a photographic project by Edgar Martins and Jordan Baseman, this exhibition presents two series of work that invite us to reflect on how we deal with death, as a society and individually. In Liverpool through April 3rd.

Medical Oddities Of Alice: Potions, Poisons and Pathology, on March 15th in Philadelphia.

Bone Cleaning Class will provide an introduction to the different methods of preparing bones. The class will take place on March 25th and 26th, in San Francisco.

More Beyond exhibition, curated by Rebecca Reeves opens on April 2nd at the Brick and Mortar Gallery in Philadelphia.

Corpses, Cadavers and Catalogues: The Mobilities of Dead Bodies and Body Parts, Past and Present, an interdisciplinary seminar in London, May 17 & 18.

Forget me Not: Planting a Cemetery Garden with Nicole Juday. Learn which plants were favored for grave gardens during the Victorian period on March 17th, in Philadelphia.

Everything Dies! Coloring Book Tour may be coming to a town near you. Written and illustrated by Bri Barton, this death positive coloring book is for everyone and we are BIG fans of it!

February 28, 2016

ASK A MORTICIAN – Shrunken Heads

February 19, 2016

When Funeral Directors Go Bad

February 2, 2016

Facing Mortality Through A Lens

I have a qualification in modern literature and I am a self-taught photographer. In the beginning, I took pictures on the street (street photography). Then, I immersed myself in the world of the hospital because I wanted to “test my ability to adapt” – to see if I could challenge myself by confronting painful topics affecting the vulnerability of the human. I asked myself – was I emotionally and intellectually able to turn a photographic eye on that which is most intimate in others? This became my starting point.

University Hospital was the first to accept me into their neonatal unit and this experience affected me deeply. The hospital is indeed a fantastic human laboratory that allowed me to grow professionally by confronting me with the photographic requirements of immersion report. Through these photographic experiments in neonatology, hematology and palliative care that formed my photographic eye, I could approach other subjects with great sensitivity. I honestly think that I could not photograph in the same way if I did not have my eye initially trained at the hospital. Indeed, these photos “live inside me” and I often think of caregivers and patients that I photographed. They are part of me.

I did not choose neonatology, instead neonatology chose me as it was the only unit that would allow my presence.

I thought it was good to start with birth, the beginning of all human existence. Through this work, I wanted to highlight the human skills of caregivers, their ability to provide comforting gestures, empathy for those children born prematurely. I wanted to show that the technical aspect, which is certainly essential to the survival of these children, is not the only predominant need and that human touch, even if it seems more subdued, is still an essential part of care.

My approach was identical in the hematology department. It can be said that these more “sensitive units ” need “professional gratitude” or reverence among the caregivers.

At 23-years-old, I lost two of my best friends in a tragic accident. I was able to painfully measure that our supposedly civilized society denies death and the mourning that follows. In France, there are now psychiatrists who specialize in bereavement care, as if it were a neurosis to overcome. At this pivotal moment in my life when it was necessary that I accept the unacceptable and I also recognized the awkwardness which seemed to paralyze my friends from mourning.

But death is inevitable and we must find ways to face it. From where do our fears come from? How can we express our grief and accept the death of others? How do we prepare ourselves for death? All these existential questions are ignored as we are pressured to exist now. As society denies death by hiding it behind the sterile walls of the hospital, I made the therapeutic and artistic choice to actively immerse myself in the world of the hospital.

I wanted to demonstrate the richness and quality of a life ending, through the care of medical professionals and volunteers.

I believe that the concern for others in the palliative care unit is the essence of our humanity. It is in this moment of vulnerability, in dying, that we will all experience – when we long for a look, a gesture that denotes attention and respect, and us with the feeling of still being a human being.

Through photography I wanted to focus on the two topics of neonatology (birth) and end of life (death) – to show that death is part of life and it is also as natural as birth. I also wanted to highlight the same gestures of nurturing, comforting and consolation in these two units.

Through photography I wanted to focus on the two topics of neonatology (birth) and end of life (death) – to show that death is part of life and it is also as natural as birth. I also wanted to highlight the same gestures of nurturing, comforting and consolation in these two units.

No gallery has agreed to show such a project. My photos are condemned to be seen in the corridors of hospitals, compartmentalized in this institution, which is currently the only response of a society that sees death as a failure.

Personally, the reactions aroused by my chosen subjects have always been guilt-inducing. Some saw this choice as an abandonment of the artistic dimension of my work or they insinuate morbidity or even voyeurism. My only creed and my personal conviction was to answer them. “I am a Man and nothing that is human is foreign to me.” (citation of Térence) Alas, death and end of life are still a very taboo subjects in France.

To integrate or at least come to be accepted in a hospital is always my first challenge – my eternal rock of Sisyphus. The first time I entered a chamber of the palliative care unit, it was in Lily’s room – she was suffering from generalized cancer. As I was barely through the door, the nearby church rang the death knell and she asked me, without giving me the time to say hello, if the bell is a death knell or wedding bells. The vivacity of her question surprised me and I could only answer, “A funeral.” Her reply was straightforward – “I’m afraid…” and that was the beginning of a beautiful relationship between photographer and subject. She tested me and I had won her trust by not disguising her reality. For Lily, I was able to truly hear her and not overshadow her fears with my own.

This is another picture of Lily being comforted by a caregiver. In the last days of my story, Lily was accustomed to awaken in an alarmed state several times a day as she was afraid to fall asleep.

I have wonderful memories of the palliative care staff. This is a great living experience – everything is life and given over to life: laughter, tears, anger, grief, joy, complicity.

The hierarchy of hospital positions are meaningless here. All caregivers, including those responsible for the cleaning are invited to the meetings and all the uniforms are identical.

Six months after my father’s death , I went back to work in a hematology department. Here, I focused on the daily life of caregivers.

In these two photographs, the central subject is the patient. The memory of my father and the last moments I spent with him will always interfere in these two pictures. He also had moments of silence, solitude too, even though he was surrounded by relatives or caregivers.

The bed, the sheets are dramatized as funeral rites.

Through my photographic work and the wider dissemination of it, I sincerely hope to help our societies to put aside their own fear of mortality and begin to look at life from a thorough understanding of death; inviting us all to participate fully in the great adventure of life, without apprehension.

Sylvie Legoupi’s work can be found on her website.

January 28, 2016

Happy 5th Anniversary, Deathlings!

Me.

Five years ago today, this website launched to the public. Back then I was but a young mortician with modest goals and dewy hopes; fresh-faced, optimistic. Little did I know that I would spend the next five years morphing into the cruel hag creature I’ve become, a Renfield/Igor-like minion to death culture. What can I say… my story truly is the American dream.

This is a note to thank you for how far we’ve come these five years, and to remind you that we still have a long way to go. People all over the world want a chance to die better; to fear the spectre of death a little less. That desire has led to more people taking charge of their own death, more opening of natural cemeteries and offerings of greener options, more coverage in the media. But there are many still suffering– dying long, drawn out deaths they wouldn’t have chosen, leaving things undone and unsaid, engaging in death rituals that no longer hold redemption or meaning to them. Our cultural death denial is deeply entrenched, and we have only just begun to claw our way out of it.

Every step of the way, my own advocacy (and I think I can safely say the advocacy of my colleagues) has been profoundly influenced by you– the people who support, follow, and live the tenets of the movement.

The choices I’ve made and the projects I’ve undertaken (pun intentional) have always been in response to what you have shared with me. One of the best examples of this, is the use of the term death positive to describe what our movement is and what we advocate for.

I’m lucky to know a number of advocates in the sex positive community. My understanding of sex positivity was, in part: “I’m fascinated by human sexuality and my own relationship to sex and I refuse to be ashamed of that interest.”

I was sure if there was sex positivity, there would also be death positivity. But when I did the deep dive Google search, nothing. So several years ago I asked the Order of the Good Death’s Facebook and Twitter community about why that might be. As always, you had brilliant thoughts that helped shape what the death positive movement has become.

You also gave me the confidence to go ahead with using and promoting the term across my work.

Death positivity is saying, “I am fascinated by death, the history of death, how cultures around the world handle death, my own relationship to mortality, and I refuse to be ashamed of that interest.”

I may be preaching to the converted here, and perhaps you don’t need to hear this. But please, don’t EVER be ashamed of that interest. The only way we our going to change our messed up relationship with mortality is if people aren’t afraid to be really, truly interested. Fascinated. Enthralled. Devoted.

The work we do now will affect our future.

You constantly say that you want more ways to interact with both members of the Order and other people who share your feelings about death. We hear you, and are trying to make that a priority this year.

Here is a new video about three initiatives we’re launching:

The #DeathPositive Hashtag

The r/DeathPositive Subreddit

The Death Positive Pledge, a place to join the Order of the Good Death.

We asked three of our beloved Order members what Death Positive means to them. Here’s what they had to say:

My whole life I have been called “morbid” because I was interested in death. At a certain point I thought to myself, “what is so morbid about thinking about death, if everyone who has ever lived has died, and everyone I know today will die one day? Why is it morbid to spend time thinking about one of the great mysteries of human life, the foreknowledge of which arguably creates the human condition, and is the root of so much of art, culture, religion, and philosophy?”

Joanna Ebenstein, founder of the Morbid Anatomy Museum

There is so much potential for expanding and improving the way we do death. Imagine if we envisioned ourselves as part of the lifecycle, where dying was as wonderful and important as being born. It gives me shivers to think about how much better we can do.

Katrina Spade, founder of Urban Death Project

The last decade has been an extremely exciting time to work on all things death positive. There was a different time, not so long ago, during the era of 1980s/1990s AIDS protests and end-of-life activism pursued by ACT-UP, Queer Nation, and the Gay Men’s Health Crisis in New York that the term death positive meant something extremely different than today. The very idea of connecting death and positivity created a political urgency that thousands died pursuing. I think that today’s death positive activists should reflect upon this recent past in order to understand how pursuing end-of-life activism, both today and in the future, builds on many lives cut short far too early. The future of death positivity, I think, lies in seeing how its past incarnations most certainly created an activist playbook for the future. To me, this re-engagement with death acceptance is an extremely positive and hopeful development that in turn supports and encourages the end-of-life conversations happening everyday.

Dr. John Troyer, Director of the Centre For Death & Society

Here’s to a year of growth, both in your personal relationship with death and of the movement.

Welcome to my Sad Little Death Party!

January 23, 2016

ASK A MORTICIAN – Do Hair & Nails Grow After Death?

Caitlin Doughty's Blog

- Caitlin Doughty's profile

- 8411 followers