Caitlin Doughty's Blog, page 37

January 14, 2016

January 6, 2016

My Uncle’s Good Death: In Memoriam

My uncle Alex was a man that taught me that in the hardest of situations, a solution could always be found. He was the glue that held together my dysfuctionally-functional family and served as my own, personal voice of reason. That voice has now been silenced. It wasn’t supposed to be like this.

Prior to my acceptance into the Mortuary Science program at Cypress College, my uncle started getting sick. According to the doctors it seemed his symptoms were that of a stroke. As the time went by, my uncle started to make fewer appearances at family gatherings. The next time I saw him, his movements were physically slower. He would speak fine, but his mouth looked out of sync when he would talk. His steps were slower, and his legs would quiver at random times. The following year, my uncle was noticeably thin and needed an aide to walk. He would ask about how my education was going and tell me what a “chingon” (ass kicker) I was when I brought home an A for an English Literature class centered around The Prince by Niccolo Machiavelli. It was this book that he gave to me in 7th grade.

That summer we learned my uncle had been suffering from ALS, also known as Lou Gehrig’s Disease, or its medical name Amyotropic Lateral Sclerosis. There is no cure.

Eventually, he became depressed and had tantrums, and regressed to childlike behavior as he struggled to understand what was happening to him. I was told it was unbearable to watch.

In December I was accepted into the Mortuary Science department of Cypress College. I was finally going to be going to school majoring for a career I have spoken about since childhood. The first person I called was my uncle. Sobbing, he said, “I am so proud of you. You’re gonna make me so proud.”

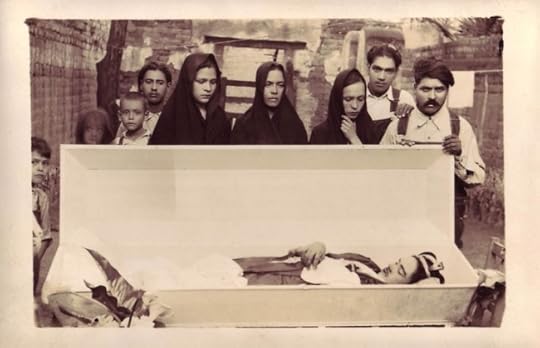

During one of our visits, I told my uncle about funeral customs in the Victorian Era and how before funeral homes existed, families of the deceased would care for them at home. I also shared that California was a “Home Death Care” state, meaning that legally the involvement of a funeral home was not necessary.

In turn, he shared with me the traditions of his family in Mexico, which are still practiced.

One day I stayed with my uncle while the rest of the family went out to run errands. He was now wheelchair bound and his speech slurred a bit more, but he tried hard to speak clearly, “Mijo, this disease is going to kill me. I’m scared for what is going to happen to the family when I am gone. I need you to promise me a few things.” I looked at him listening intently. “I don’t want to be buried. I want to be cremated. But I know that there will be issues no matter what happens. I trust you to take care of this. Remember how you told me about the home funerals? I want that. I don’t want any stranger to have me knowing that I have someone to take care of me. When the time comes, I know you’ll know what to do.”

On the morning of May 1st, 2015, I had a sense that something was wrong. During lab, I got a call from my mother confirming my fears. “Herman, baby, I’m sorry to call you while you’re at school. Mijo…your uncle died not too long ago. We don’t know what to do. We need you. Please call me as soon as you can.”

Although I had previously done many services for families at work, and helped dress, casket, and cosmetize human remains, there is really no way experience or funeral service education can prepare you for when a death occurs in your family.

As I approached the house, some family members looked at me. A woman on her knees who had been crying got up, crying out, “Don’t take him from me!” It was clear that some were under the impression I was coming to take my uncle away and they would no longer be able to see him. I spoke with the social workers from the hospice agency and told them what was to be done. I worked my rounds to see who was there, and ultimately the condition of my uncle’s body.

My uncle was in his room on his bed. The family was praying over him. After half an hour, I entered the room, not knowing what to expect. I hoped that decomposition would be delayed as long as it could. I had done extensive research on home death care, but I wasn’t prepared with all the necessary tools such as dry ice to inhibit decomposition.

I saw my uncle’s body lying lifeless on his bed as if he was tucked in to sleep. As corny as it sounds, he looked truly at peace, a small grin showed on his face. “You motherfucker. You weren’t supposed to die before me…who is going to keep this family in line now that you’re gone?” I whispered. As I touched his hand it was warm. I checked for post mortem issues but found none. I noticed he was dressed in his favorite soccer clothes. The hospice nurse and my aunt had shaved him, given him a sponge bath and dressed him. It is morbid to say this, but damn if my uncle wasn’t the best looking corpse I have ever laid eyes on.

That afternoon family members began to arrive. My uncle was the prime exhibition tonight, as a vigil was held over him. By evening, about 300 people were here. Some were paying their final respects to my uncle in his room, there was a priest in the backyard giving a sermon and afterwards, eulogies were said. I felt my uncle’s presence strongly. “This is what it is all about. This is how death should be celebrated,” I thought.

Throughout the day, the one question I was repeatedly asked was, “Is this legal? Are we really allowed to do this here?” I was grateful to answer that question, rather than having to address the question I was dreading but ultimately, was never asked: “Why are we doing this?” It wasn’t a macabre thing in anyone’s mind to have my uncle here in his home.

As the night drew near I was asked to delay the funeral home from coming to pick up my uncle until the morning. “But only if it’s legal,” my family kept repeating. At midnight, I sat by my uncle’s side and I told him about the big turnout for his day. My uncle’s family never left his side as they retold stories and reminisced about his many quirks and lessons taught by him throughout the night. It was a “Good Death” if I ever saw one.

26 hours after the death of my uncle, I was carrying him across the hallway to be strapped onto a gurney where he would be taken to the funeral home that would process his cremation. Everyone agreed they were finally ready to say goodbye. And with that, my uncle was driven away as his last wishes were carried out, just as he had wanted them to be. Days later, his witness cremation would take place, and as my cousins and aunt said one last, private goodbye, I whispered that I was going to make him proud.

Tio, I hope you still are.

Herman Reyes is a licensed funeral director in the state of California. He currently shares his experiences as mortuary science school student on his blog, Adventures In Deathcare. You can also find Herman on the Adventures In Deathcare Facebook Page.

December 20, 2015

December 10, 2015

November 30, 2015

Calendar of Events – Winter 2015-2016

January 4, 2016, 7 pm at the Urban Death Revival in Seattle (Sole Repair Shop 1001 East Pike Street, Seattle) Tickets go on sale January 4, 2016.

DEATH SALON

Save the Date! Our next Death Salon will take place in Houston on September 17, 2016 in partnership with the Aurora Picture Show! This will be our very first Death Salon Film Festival – submissions are currently open. Please visit the Death Salon website for details and be sure to sign up for the mailing list.

ORDER MEMBERS

Annabel de Vetten-Peterson of Conjuror’s Kitchen will be hosting a 4D screening of The Nightmare Before Christmas in 4D – enhanced with scents and edibles. on December 15th and 16th at The Electric in Birmingham, UK.

Sarah Troop will be speaking at Obscura Society LA event, The Disneyland of Death at Forest Lawn, on December 6, in Glendale, CA.

Cassandra Yonder‘s BEyond Yonder Virtual School for Death Midwifery in Canada’s core 12 week program begins January 4, 2016.

John Troyer‘s project the Future Cemetery is running a design competition, Future Dead: Designing Disposal for Both Dead Bodies and Digital Data. Registrations will be accepted until December 5, 2015.

Rachel James’ latest project, Posey Filled Pockets is hosting a variety of events all winter long – Cocktails With Corpses, Breathing New Life Into Death and Death Eaters in Grass Valley, CA. Dates and details right here.

INSTITUTIONS RUN BY ORDER OF THE GOOD DEATH MEMBERS

The following institutions are run by members of the Order and offer a full calendar year of death positive events that are open to the public.

The Body Appropriate, located in San Francisco, is run by Order Member Stephanie Stewart-Bailey. This season, The Body Appropriate will feature a Sound Public Dissection, Visceral Cinema and more. Check the out the entire schedule here.

The Body Appropriate, located in San Francisco, is run by Order Member Stephanie Stewart-Bailey. This season, The Body Appropriate will feature a Sound Public Dissection, Visceral Cinema and more. Check the out the entire schedule here.

Join Technical Curator, Carla Valentine for an incredible array of events inside a stunning Victorian pathology museum in London. Throughout the upcoming season you can attend the incredible Barts Bazaar or a special Christmas event on ghost stories. See these and so much more on the Barts Pathology Museum event page.

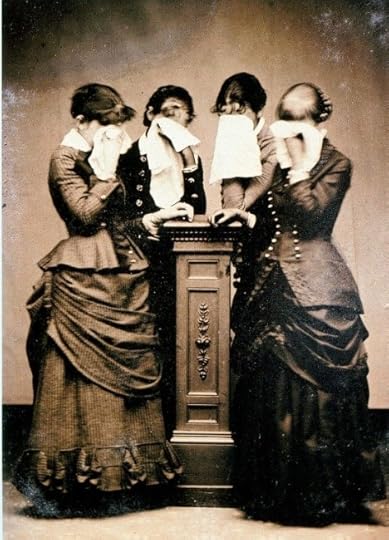

Joanna Ebenstein’s incomparable Morbid Anatomy Museum in Brooklyn should be on every Deathling’s bucket list. In addition to visiting the museum you can catch any number of workshops, field trips, lectures and unique events. Coming up this season you can attend a taxidermy class, a Victorian Hair Art workshop or an illustrated lecture on the portrayal of death and grief. Visit their website for a full listing of events and visiting hours.

Joanna Ebenstein’s incomparable Morbid Anatomy Museum in Brooklyn should be on every Deathling’s bucket list. In addition to visiting the museum you can catch any number of workshops, field trips, lectures and unique events. Coming up this season you can attend a taxidermy class, a Victorian Hair Art workshop or an illustrated lecture on the portrayal of death and grief. Visit their website for a full listing of events and visiting hours.

OTHER DEATH POSITIVE EVENTS IN WINTER 2015-2016

We know Krampus doesn’t exactly fit the death positive mold, but we thought you Deathlings would still appreciate knowing where to find him — before he finds you!

We know Krampus doesn’t exactly fit the death positive mold, but we thought you Deathlings would still appreciate knowing where to find him — before he finds you!

In Los Angeles there is plenty to choose from – lectures, traditional Krampus plays and the Krampus Ball. Check out our friends at Krampus Los Angeles for the full line up.

In New York the Morbid Anatomy Museum has you covered with their Annual Krampus Costume Party! There will be an opportunity to be immortalized in the Basket for Naughty Children, a Krampus Photobooth and win prizes in our annual Krampus Costume Contest, and much, much more!

Bloomington, Indiana hosts a Krampus Night event with a parade and activities for your wee deathlings, too!

Marginal Death Research: Doing Edgework on December 2 at the University of York.

How to Die Like a Victorian with Holly Carter-Chappell on December 2 at the Florence Nightingale Museum.

Death and Identity in Scotland on January 29 – 31, 2016 at the New College, Edinburgh.

Spirits of Christmas Past: Laurel Hill’s Yuletide Connection on December 19 at Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia. Take a walking tour of the cemetery and hear how the spirit of the season is forever embodied at Laurel Hill.

Death: The Human Experience is an art exhibit that explores the human response to death through hundreds of objects and stories from across the world, from ancient times to modern day.

November 27, 2015

November 21, 2015

Paris, 13 November

Paris, 13 November.

Friday night. I’m home with a bad cold. I get the news. The first Paris friend who texts me to ask where I am and if I’m safe makes me cry. I’m so grateful anyone would even give a shit.

I’m scared. Will they spread out through the city? Will they come here? Until I remember that my very Jewish quartier is heavily patrolled by armed National Guard thanks to the Charlie Hebdo attacks. It’s fucked up, but it makes me feel safer.

I stay up until 3am anyway. I notice my neighbor doesn’t come home. I feel vulnerable, frightened again — he’s Muslim. I’m worried he’s somehow caught up in all this, and he’ll come back and kill me too, even though he’s a nice guy. Once as I was heading out in my famous blue coat, he stopped me in the hallway and told me I didn’t need it because it was really warm outside. Such a small thing, the kind of thing your mom says, that only comes from an everyday kind of love, and easy kind of care. I’m ashamed to admit to myself that even despite this, deep down I’ve been a little frightened of him all along.

Sunday afternoon. I’m visiting a friend and her baby. She gets a cryptic call from one of her husband’s employees: he tells her not to worry. She asks if something’s happening. He says yes and hangs up. I watch her try not to panic–aware the tension is so high, aware people are a little goofy sometimes, aware her baby can pick up her fear. We check our phones, check the news. Learn soon enough of a false alarm in the Marais and at Republique — where her husband’s restaurant is. We learn firecrackers went off in the Marais, someone drove by Place de la Republique screaming about a man with a gun. We learn the Place cleared out immediately, everyone in the restaurants hit the floor without really knowing what was happening — but we all know why. They stayed there for 10 minutes, and then learned it was nothing. Exhausted and angry, cheated of 10 minutes of their lives, thinking they were the last 10 minutes they would ever know.

I still haven’t heard my neighbor come home. My fear of him has changed to fear for him. I can’t check the victim rosters; I never learned his name.

Monday. Emails and messages are still trickling in: are you ok? I simply say yes and then get apologetic excuses for not asking earlier, mistaking my short reply for petulance instead of the reality, which is that I have nothing else to say.

The Facebook flags, the solidarity, the defiant memes and complaint memes and outrage and theories and cries in the dark: what about us? They’re all popping up, blossoming, flourishing. I don’t want to engage. It’s a delicate time, a dangerous time. Footage of Sunday’s false alarm also makes the rounds, mostly news footage of interviews suddenly interrupted, a terrified glance at something off-camera, people fleeing. The cold dry panic on the faces in the restaurants as they seek the floor, pile up the tables against the doors. Waiting to see if it is their turn to die.Despite the defiance, the cris de coeurs of mini skirts and music, of terraces and champagne, those images from Sunday’s false alarm stick with me more, belie the tidal wave of fear just there, in the corners, ready to flood in, that national pride and humour are meant to keep at bay. I hate it, the defiance, but it’s all so human too. It’s hard to hate that.

I work up my nerve and knock on my neighbor’s door. His voice from inside makes me jump. He opens the door. Relief. I explain I was worried about him because I hadn’t heard him come home for three days. He says thank you, that’s very kind. I don’t think to ask his name. He doesn’t ask mine. Nothing has changed.

I tell someone I have a crush on that I like them. I figure no one has anything to lose at this point, not any more than we’ve all already lost. Apocalyptic thinking, I call it. It’s a stupid thing to do. Why not tell people when life is fertile and full of promise? Why wait until you have nothing to lose? I’m a hypocrite. And hindsight is 20/20.

I realize I need to make love. I need to connect with another human, get deep inside someone. Let them get deep inside me. Just to feel it. Just to say hello.

Monday night. A Russian artist who will stay with me for a week arrives. It’s his first time in Paris. He tells me that he uses his art to deal with the tragedy, the fear, the pain, the travesty of governments and justice and religions gone awry. He says it works, making art helps him go on. But just before he came, he went to a meeting at his art collective. All they talked about a refugee woman recently arrested in St Petersburg for not having working papers. Her 5 month old baby was taken from her. The baby dies in custody a few hours later. It doesn’t work for that, he said. It doesn’t work for that.

Tuesday. I show the Russian artist around my quartier, bubbly and chatty. Until we get to a restaurant I know, that I go to from time to time. I like it there. It’s closed, barricaded with flowers and cards, notes and drawings. Notre Belle Equipe, they say. Three servers and the wife of the owner were killed on Friday, out celebrating a birthday among them. I’m amazed at how fast my mood drains, how quickly I fill up with sorrow. And fear, the fear creeps in too, again: so it comes closer. That long, craggy finger of the terrorist attacks… it’s almost touching me. I recoil. We all do.

Tuesday night. My string instrument class at the Philharmonie. For the first time, the instructor remembers to take attendance at the end of class. It’s a cacophony — everyone scratching away on their instruments while he calls out names. We’re all here! he declares over the noise. Someone very quietly says “nous manquons une”. Silence. We all know what it means.

I take a long walk, wind up in a funny little corner bar near my place. It’s late. I’m the only one at the bar. I order a wine, then a whiskey. A woman my age comes in, takes a seat a stool away. Orders a whiskey and a water back. A few minutes later, another woman about the same age comes in. She knows the bartender and his helper, gives them the bises. Orders a whiskey. It’s after midnight, almost one. Three woman in their 40s, drinking whiskey at a bar. We talk about the restaurant in our quartier, our neighborhood’s loss. The bartender puts on Gil Scott Heron’s “I’m New Here”. We listen.

Susie Kahlich is an American writer who has been living in Paris, France since 2010. She works as a broadcaster and arts journalist, making art accessible to people who are intimidated by art. She hosts the weekly radio show, Expo Paris, a personal journey or carnets de voyages through the biggest museums and the smallest galleries for World Radio Paris. Her fiction has been featured in Estomac Onirique, Her Royal Majesty, and The Artist Catalogue. She is currently working on an opera electronica, The Beautiful Now, an eight-movement cycle about life and death.

All photographs courtesy of work4food project

November 12, 2015

November 9, 2015

To live and die (and live again) in Bolivia: the Fiesta de las Ñatitas

Yesterday morning was a very special day for little Miguel. His family had taken pains with his appearance on this day, and he looked resplendent. Bundled warmly against the cold morning air, he was taken to a chapel in their native La Paz, Bolivia, and seated with pride directly in front of the altar. This could be the beginning of a story about a child’s Baptism or first Communion. But despite Miguel’s diminutive size, he is not a child. Nor in fact is he a living person.

Miguel is a human skull. Not just any skull, however. He is what is known as a ñatita, a local Bolivian slang that means a “pug-nosed one,” roughly referring to the flattened appearance of human crania, but one which exercises certain beneficial powers. How and when death came to the person from whence this skull came is unknown—it gives the appearance of having been that of a teenager, and was acquired nine months ago from a friend at a dental school. At the school, it was simply a specimen, but given over to a family, one which subscribes to local beliefs about the powers inherent in skulls, it became kin . . . it became Miguel. And it became a ñatita. Cared for and treated as an esteemed member of the household Miguel used his abilities to protect his newfound family and bring them good fortune. And yesterday he was taken to his first Fiesta de las Ñatitas.

There he would be celebrated among thousands of his kind—thousands of skulls that have taken up residence with local families and established similar bonds. The Fiesta is a chance for those who care for these skulls to thank them publicly for their services. Some of their accomplishments are impressive, others seem mundane, but in a decade of coming here to document the festival and interview its participants, I have come to know many of them well. Marcos, for instance, arriving in a humble cardboard box, is credited with having prevented burglars from entering the home of his owner, an elderly woman. Meanwhile, Andres, in a carved wooden shrine, is said to have aided his owner with his studies in medical school and helped him on his way to becoming a prominent physician. Esmeralda, crowned with a floral wreath and seated on a green velvet cushion, advised her owner so astutely on business matters that he now runs one of the country’s most profitable import/export companies. These and so many more were present in the chapel at La Paz’s sprawling Cemetery General, which every November 8 holds the most elaborate Fiesta de las Ñatitas. Estimated to be the largest ever, yesterday’s celebration saw over ten thousand people come through the gates. They came to celebrate an incredible bond, one that is simply unimaginable in modern Western society, where the dead have become ghettoized and stigmatized as an abject group. The bond is not between the living and the dead, however, because to those assembled at the Fiesta the “dead” are in fact still a vital and sentient group. The bond is simply one between friends, who on one side happen to be living, and on the other side happen to be dead. But that difference is seen as flimsy and inconsequential, because for those who subscribe to the powers of the ñatitas, the divide is easily crossed. For those who do not, however, it is wholly perplexing phenomenon.

The ñatitas: whose skull is it, anyway?

It’s possible to find people at the Fiesta de las Ñatitas carrying skulls of loved ones—one woman with whom I am acquainted brings the mummified head of her husband each year, and others bring fathers, mothers, aunts, uncles, or even children who died prematurely. Outsiders tend to assume that there must be some preexistent relationship between the skull and the people who care for it, but in fact this is seldom the case. Take, for example, Miguel in our introduction—there is no known provenance to the skull, and the family which now treats him as one of their own has no idea who he (or perhaps even she) may have once been.

The skull which becomes a ñatita is, in the vast majority of cases, that of a total stranger. Anonymous crania may be acquired from various sources, including medical schools and archeological sites, but most commonly they are acquired from grave diggers. At La Paz’s General Cemetery, for instance, gravesites are not purchased outright, but rather leased, and when some future generation eventually lapses in payment the bones of the deceased will be removed. Those who have been exhumed are supposed to be incinerated, and their ashes dumped in a common grave, but their skulls are often brokered by those who work at the cemetery.

If this anonymity seems vexing, it must be understood that the ñatitas are steeped in the idiosyncratic ways that human spiritual nature was conceived of by the Aymara, the indigenous people of the local highlands. They traditionally believed that a person’s spirit is comprised of multiple manifestations of ajayu, a word is typically translated as soul—it’s an awkward translation, however, since the ajayu is more subtle and nuanced than the Christian conception of the soul. There are greater and lesser aspects of ajayu which together form one’s character attributes, but after death may separate into unique entities.

Thus, the spirit that manifests itself as a ñatita may not necessarily be of the same identity as the person whose skull is in question. This, of course, makes it easier to bond with the skulls of strangers, but I have also encountered cases where crania of known provenance were housing spirits of alternate identities. In one instance, a woman explained that the skull she carried to the Fiesta was that of her uncle Fernando, but that the spirit which communicated with her was a girl named Ana Maria. In another, a masculine spirit named Fidel was manifesting itself through a skull known to have been that of a young girl. It’s not as schizophrenic as it may sound, if one acknowledges that each of us, in the makeup of our character, is really an amalgamation of several different and even conflicting aspects: different measures of impetuous, wise, youthful, mature, strong, weak, and so on, all of which coalesce to form our personality. As for the particular spirit which will communicate as a ñatita, once a bond is established it will reveal an identity, often during a dream, and open a dialogue with its living benefactor. This person will then perform rituals and makes offerings in its honor, and over time the two parties will become intimately connected, establishing a relationship similar to that between close family members.

The skull will be kept in a shrine within the home, surrounded by cigarettes, bags of coca leaves, flower petals, and other small gifts which have been left for it. It may also be given characteristic decorations, with cotton balls in the eye sockets (to replace its missing eyeballs), and tin foil around its jaws (as simulacra for lips) being most common. A single ñatita will be enough to provide luck, tranquility, and protection for a household, but in some cases several skulls, each with a different set of powers, may be present. It is common, for instance, to find multiple ñatitas in the homes of local yatiri, an Aymara term for a healer or spiritualist. Their residences are treated as neighborhood sanctuaries, and locals who lack their own ñatita will often select one among the skulls there as their patron, and visit frequently to offer prayers.

Some of these collections are extensive. The largest has grown to 54 and turned the living room of its owner into a small scale charnel house. Perhaps the most famous, however, is a set of 18 ñatitas belonging to a yatiri named Doña Ana; these skulls have developed a sizeable cult following and are considered by many to have miraculous powers. Each skull has its own area of expertise, including health, love, finance, school work, and domestic matters. Housed in a special room lit by candle light, Doña Ana’s ñatitas are often surrounded by a throng of worshippers. Lest there be any doubt about the effectiveness of her skulls, Doña Ana keeps a pile of written testimonials affirming their prowess.

Straddling two worlds: the living dead

Surrounding Doña Ana’s enshrined skulls are small images and statues of Catholic saints. This is typical—Catholic symbolism such as the Rosary, Virgin Mary, and Christ blessing are almost as ubiquitous as coca leaves when it come to the ñatitas. Added to the fact that the Fiesta takes place in a chapel a week after All Saints and All Souls Days, at the end of the Octave of the Dead, there is ample evidence that some level of syncretism between indigenous Aymara and traditional Catholic beliefs has gone on. Indeed, those who bring arrive at the cemetery toting skulls universally consider themselves to be both good Catholics and Aymara, and do not see any conflict between the two. The process of syncretism is more superficial than it initially seems, however, and the veneration of the ñatitas has proven highly resistant to Western attitudes towards death. Despite being held in a cemetery stocked full of skulls, the Fiesta is in no way a celebration of death, and those gathered in attendance will take umbrage at any insinuation that it is morbid.

All photographs by Paul Koudounaris

Paul Koudounaris is an author and photographer in Los Angeles. His PhD in Art History has taken him around the world to document charnel houses and ossuaries. His books of photography include The Empire of Death and Heavenly Bodies, which features the little known skeletons taken from the Roman Catacombs in the seventeenth century and decorated with jewels by teams of nuns. His other academic interests include Sicilian sex ghosts and demonically possessed cats. For the past several years Paul has travelled to Bolivia to photograph and research Fiesta de las Natitas.

November 6, 2015

Caitlin Doughty's Blog

- Caitlin Doughty's profile

- 8408 followers