Caitlin Doughty's Blog

September 16, 2025

On Bodies and Embodiment

In the ethnographic study Shelter Blues: Sanity and Selfhood Among the Homeless, anthropologist Robert Desjarlais considers the experience of homelessness through various lenses, including culture, language, health care, and political agency. Desjarlais notes how journalists and the media tend to focus on the grotesqueness and the inability of unhoused people to contain their bodily needs and afflictions, displaying them as pitiful figures in an effort to draw attention to the issues of homelessness. But in doing so, they spectacularize and other the bodies of those who are homeless and, in effect, individual homeless people: “For [those in the media], homeless [people] are those who fail to restrain their bodies from an outpouring of scat, urine, words, or outstretched arms; they offend a spectator’s sensory faculties.”

Body (noun) | /ˈbä-dē/ | —the physical structure of a person or an animal, including the bones, flesh, and organs; the trunk apart from the head and the limbs; the physical and mortal aspect of a person as opposed to the soul or spirit; the main or central part of something,especially a building or text; a large or substantial amount of something; a mass or collection of something; a group of people with a common purpose or function acting as an organized unit; a mass of matter distinct from other masses. (Oxford Languages)

Our bodies, and the fact that they will all die and decay one day, is something we all have in common: We understand pain, shivering, fever, itch. I don’t believe it’s possible to talk about death or homelessness without talking about the body. Both things bring the physicality and temporality of our existence to the forefront in ways that we can ignore or deny in other aspects of our daily lives. Death leads to the decay and destruction of the body, and homelessness has immediate visceral effects on the body through exposure to the elements, lack of nutritious foods, injury, illness, restricted access to health care, and violence. Therefore, it felt unsurprising that my exploration of the body intersected with the research I was doing around dying while homeless. Yet I could still hear Desjarlais yelling from the pages of his book, “Shame, shame!”

Was I wrong to be focusing on the bodies of those who were homeless, spectacularizing them in an effort to induce empathy? Did my white, safe, housed, privileged body have any right to comment? On the other hand, it’s not possible to talk about life and death and the inequalities and disparities that exist for the unhoused without talking about the physicality of such an experience. The body can be an entrance into seeing the person, the mind, and the humanity without reducing someone to only the physical.

It’s a difficult proposition: wanting the housed to understand the unhoused by means of physicality, wanting to show both the horrible and the beautiful, the wretchedness and the survivorship. Yet such an approach risks ostracizing, othering, and marginalizing the experience of homelessness by parading it as a tourist attraction, something that unhoused people can dip into and out of, returning to relative comfort, rather than as a way for those unfamiliar with the homeless experience to develop a better understanding of and empathy toward it.

However, the body also provides the opportunity for us to become more intimately familiar with death and homelessness. Once a year, across cities in the United Kingdom, there are sleep outs, organized events that bring people together to sleep outside, usually in the late autumn, to raise awareness and money toward ending homelessness. A sanitized simulation of the real thing, sure, but a physically powerful one nonetheless. It’s perhaps the closest way someone can physically embody one small facet of an experience that they might otherwise not know: Teeth falling out from years of alcohol abuse and lack of necessary dental care, staples in the head causing radiating nerve pain down the length of the body, trench foot from sleeping under bridges on rainy nights, blisters on feet from ill-fitting shoes and constant walking, eight toes down to the nubs—a result of frostbite after nights outside in a New England winter, sleeping in the backs of abandoned cars.

Those experiencing chronic homelessness will certainly suffer effects to their physical self, their lived bodies. But it’s also evident how those physically visible effects can play out in a larger context as symbols and metaphors that relate to culture, society, and political control. Assumptions are often made about those who are homeless in relation to their levels of personal hygiene, looks, and other physical effects, and in some ways, when we see someone who is homeless exemplifying those assumptions (dirty, disheveled) this validates and confirms those assumptions. It could also be said that those physical stereotypes of someone who is homeless—including the negative connotations, moralistic judgments, and assumptions that people in that situation are lazy, have chosen to be unhoused, or are addicts or mentally unhealthy—all play into the body politic of maintaining class structures. Poor people are that way because of their own personal failings, the thinking goes, not because of systematic injustices that are near impossible to overcome.

Embody (verb) | em·body | /əmˈbädē/ | embodied; embodying—give material form to something abstract; embodiment: the representation or expression of something in tangible or visible form. (Oxford Languages)

“Homelessness denotes a temporary lack of housing, but connotes a lasting moral career. Because this ‘identity’ is deemed sufficient and interchangeable, the ‘homeless’ usually go unnamed. The identification is typically achieved through spectral means: one knows the homeless not by talking with them but by seeing them” (Desjarlais 2). Home- lessness is also often conflated with uselessness, criminality, or a lack of moral character or fortitude. Unhoused people are sometimes referred to as loitering, taking up space, dirty, or trash, thereby making it easier to justify moving them on or hiding them away, busing them out of one town and into a neighboring one, or fining them for sitting in public spaces. All this makes it easier to dispose of these humans like trash in death. You can’t be forgotten if you’re never remembered. You can’t be seen if you’re never visible.

The embodied homeless are sometimes seen as disruptive, potentially causing chaos in civilized places. They are blights on doorsteps and sidewalks, betrayed by their bodies, which transgress physically against social order. They fall out of chairs they’re not meant to be sitting in, lie limp on floors from overdose as coffee and food orders are taken and filled.

In “Contemporary Hospice Care: The Sequestration of the Unbounded Body and ‘Dirty Dying,’” Julia Lawton describes her study of the dirty, unbounded bodies of the dying sequestered within hospices when their symptoms of incontinence, vomiting, or bleeding become uncontrollable and spill forth from their bodies with impunity. Lawton suggests that one reason Westernized societies hide this away is because over time we have come to highly value independence and selfhood, the success of which can be judged by how able one is to control their bodily functions. Our identities have become inextricably bound to our bodies and our ability to control those bodies. Often the homeless are seen as lacking control over such things simply because they have no choice but to defecate, urinate, vomit, and bleed in public. The homeless body is regularly illustrated as the other—a defiance or opposition to the civilized, housed body—something that needs removing, exterminating, hiding, burying. This sometimes takes shape in the form of loitering and encampment laws to move along those without homes to places where they will not be seen.

Corpse (noun) | /kôrps/ —a dead body, especially of a human being rather than an animal; cadaver (noun) | ca·dav·er—a dead body; especially one intended for dissection. From Latin: from cadere, meaning “to fall.” (Oxford Languages)

Found: Dead man in dumpster behind Amazon building. Frozen in a position on his hands and knees, as if trying to stand, blood-stained nose and dirt-caked hands, surrounded by ice cream, bananas, strawberries, frozen pizzas, cans, and packaging.

Vulnerable bodies, indigent bodies, unclaimed bodies, homeless bodies, Black bodies, female bodies, unwanted bodies, marginalized bodies, forgotten bodies. The streets can affect a social death, where a person is not fully accepted as human by the wider society. You die a social death the day the word homeless is attached to your person. Once labeled as homeless, this identification clings to the body, to the self. Nobody, no body, deserves to be thrown out, disposed of like trash.

Body (noun)| / bä-dē/ —a human being: PERSON. (Merriam-Webster)

Reprinted from Too Poor to Die: The Hidden Realities of Dying in the Margins by Amy Shea. Copyright © 2025 by Rutgers University Press. Reprinted by permission of Rutgers University Press.

September 9, 2025

Left Behind

Thomas Wood, born in Fairfax, Virginia, was twenty-two when he enlisted in the U.S. Military on June 3, 1847, to fight in the Mexican-American War. He reenlisted numerous times until the Board of Medical Survey deemed him too worn out to continue serving. He received his final honorable discharge on November 27, 1881. Wood decided to head to San Francisco, even though he didn’t have a home, a job or any friends lined up. After his twenty-five dollars ran out, he poisoned himself.

When Wood’s body was found, his pockets contained “a bundle of honorable discharges, nicely tied with red tape, and a number of affectionate letters from a married daughter living near the old home, back in old Virginia.”

Wood’s body remained at the city morgue as folks with the San Francisco Coroner’s Office attempted to arrange an honorable burial, but many cemeteries would not take him, likely because of his death by suicide. Ultimately, he was buried in San Francisco’s City Cemetery “with no one by to say even the poor words, ‘dust to dust, ashes to ashes!’” Wood’s grave was marked with a rusty white plank bearing only a number, 1,116, that was partially buried in drifting sand just off the shores of the Golden Gate.

City Cemetery was meant to be San Francisco’s solution to the problem of Yerba Buena. The old municipal cemetery was full and falling apart. It was now surrounded by the city and located right where leaders wanted to build city hall. The transition was far from seamless. Yerba Buena was at capacity by the mid-1850s, but City Cemetery didn’t open until 1868 and didn’t see its first burials until 1870. Some of Yerba Buena’s dead moved to the cemeteries on Lone Mountain, but thousands more remained in the heart of the city.

Only 267 graves from Yerba Buena were definitively moved to City Cemetery, though there could have been more that weren’t documented. And it’s entirely possible that some of these graves were on their second move—from North Beach to Yerba Buena and then to City Cemetery. If so, these two hundred acres of remote coastal land, bounded by Thirty-Third and Forty-Eighth Avenues to the east and west, the Pacific Ocean to the north and the Point Lobos Toll Road (now Geary Boulevard) to the south, became the final resting place for them.

The city made some effort to improve the look of the graveyard with plants and shrubs, but there were no trees in and around City Cemetery when it opened, nothing to protect these graves in sandy soil from being buffeted by strong winds off the Pacific Ocean.

Almost from the start, officials at City Cemetery weren’t keeping spotless records. Despite the number on the headboard that marked his grave, Wood wasn’t the 1,116th person buried in City Cemetery. When a San Francisco Call reporter asked the gravedigger how many graves there were, the gravedigger replied, “I numbered up to three thousand, and then began with ‘one’ again.” In February 1882, when the Call ran its story on the cemetery and the fate of Thomas Wood, 4,118 people were buried there or possibly more—cemetery workers said they sometimes buried two people in one plot. It was a busy place. By 1882, City Cemetery was burying 40 people a month.

At least eleven thousand of those buried at City Cemetery were indigent, and the city footed the bill to bury many penniless San Franciscans in a Potter’s Field here. For the average resident, a grave at City Cemetery cost eight dollars; far less than, for example, the Jewish Cemeteries at Dolores Park, where plots were sold for thirty to forty dollars.

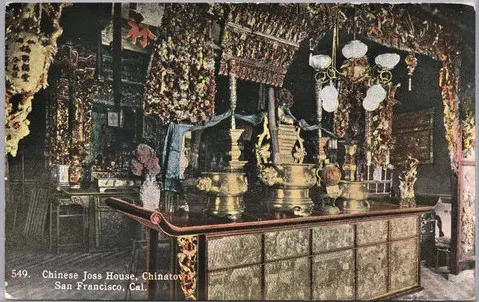

Photo of the Kong Chow Temple altar by I.W. Taber via California Historical Society Collection at Stanford.

Chinese Joss House, Chinatown, San Francisco, Cal., c. 1887

Because City Cemetery basically welcomed everyone, it included dozens of smaller cemeteries. It provided plots for graves moved from the Chinese and Greco-Russian Cemeteries and sections for Jewish, French, German, Italian, Japanese, Scandinavian, Slavonic-Illyric and Black Freemason burials. By 1887, there were nineteen plots associated with local societies and associations and another twenty-six connected to Chinese community groups. Historians believe more than 10,000 Chinese residents were buried in City Cemetery over its years of operation, though only 3,700 or so remain.

Many cultures around the world have beliefs and practices that revere their ancestors, both at home and in the cemetery where loved ones are buried. This is true in Chinese cultures; Qingming, for example, is a day of visiting ancestral graves to sweep them clean and bring offerings of food, tea and spirit money to burn along with fragrant joss sticks. Burial rites were and are also very important to these communities. Historian Wendy Rouse writes:

“Proper ritual following the death of a [Chinese] relative or friend was essential not only to the soul of the departed but also to the happiness, harmony, and well-being of those left behind. Elaborate ceremonies awakened onlookers of both worlds to the tragic event that had occurred. From the moment of death and for generations afterward the deceased were remembered in annual ceremonies performed religiously by their descendants. Thousands of miles of ocean and residence in a strange land modified, but failed to break, the continuity of these traditions.”

During the late 1800s, Chinese in San Francisco largely didn’t regard local cemeteries as permanent resting places. Most of the Chinese who came to San Francisco in the years after the gold rush planned to stay only long enough to make good money before returning home again. Chinese community associations took on the responsibility of burying their brethren in San Francisco if they died here and also handled the task of returning their bones to China after a period. Otherwise, if a body was “buried in a strange land, untended by his family, [the] soul would never stop wandering in the darkness of the other world.”

Although local Chinese societies built a number of monuments within City Cemetery—one of them, the Kong Chow Temple, remains there to this day—individual graves were generally marked with a simple board or brick painted with an inscription in Chinese.

Shantang (Chinese community) representatives kept track of graves and secured the necessary permits to disinter the bodies, typically a few years after burial. They paid $10 per disinterment to the city, $2.50 of which went to the cemetery itself. The bones were cleaned if needed and sealed in a tin box marked with the name of the deceased. They were stored in Chinatown before they were sent home to China.

Many western Europeans, including those who settled in San Francisco, didn’t understand these customs. Western traditions hadn’t placed any importance on connecting with or tending to ancestors for hundreds of years, particularly not once Christianity spread across the world. Those who came to settle and colonize North America left the remains of their forebears behind in European churchyards, possibly to never return. And what they didn’t understand, they didn’t respect.

Chinese residents of California faced horrific racism, and their cemeteries and burial rites became targets, too. White and European San Franciscans complained about Chinese burial and exhumation practices and often used the “abatement of nuisance” euphemism as an excuse to close San Francisco’s cemeteries or limit the activities of Chinese residents.

Other times, white locals didn’t bother with euphemisms; their bigotry was stated openly. The Richmond District Improvement Club was thrilled when the city agreed to close City Cemetery in the late 1890s.

In a resolution, the club celebrated “getting rid of this pest-breeding spot and forever remov[ing] from the sight of visitors to the district the pagan rites of scraping the flesh from the bones of deceased Chinese who had been buried there, which to our people was a sickening and dreaded sight, once seen not soon to be forgotten.” Meanwhile, vandals who visited City Cemetery often picked up Chinese grave markers to play with, throw at one another or steal.

Reverence for the dead in general at City Cemetery wasn’t high on many San Franciscans’ list of priorities. Even so, City Cemetery operated in relative peace for the first ten or fifteen years of its existence—that is until a wealthy neighbor moved in and, like many of San Francisco’s other rich and powerful, saw dollar signs where others saw sacred ground.

Photo courtesy of Beth Winegarner.

The Kong Chow funerary monument marks the site of Chinese burials in City Cemetery, now Lincoln Park Golf Course.

Enter Adolph Sutro

Adolph Sutro was born in Aachen, Prussia, on April 29, 1830, and came to California with the gold rush in 1850. In the 1860s, he developed and built a massive tunnel beneath the mines in Gold Country, meant to eliminate flooding and make the mines safer and more efficient. The tunnel made Sutro very wealthy, and in the 1880s, he returned to San Francisco and began buying up land. One of his purchases was that of a cottage on a bluff overlooking the ocean, now known as Sutro Heights. Another was that of the Cliff House, which he transformed into a “fairy tale Victorian Castle.”He turned his estate into an elaborate public garden decorated with statues, gazebos, topiary and much more. And he built the Sutro Baths, an extensive complex of public swimming pools filled with ocean water and heated to different temperatures. All of this was happening right next door to City Cemetery.

Sutro thought the fee to ride the streetcar from downtown San Francisco to his seaside attractions ($0.10; about $3.07 in the 2020s) was too expensive, so he built a sightseeing railroad of his own. Work began on this new railway, or “cable road,” in August 1886. As proposed, it would run west from the corner of Geary Street and Cemetery Avenue (now Presidio Avenue), north to California Street, west along California Street to Lake Street and then around the north side of the City Cemetery, ending its journey at the Cliff House. “The Sutro road will be one of the most picturesque in the country. For two miles it will command charming views of the Golden Gate and ocean, and for more than a mile it will run along the bluffs at a height of 125 feet above the level of the sea.”

Sutro’s design involved building a section of trackway near the intersection of Thirty-Third Avenue and Clement Street—right over a grave plot owned by the Knights of Pythias. Sutro had been negotiating with the Knights of Pythias for a while, and apparently, each side thought they had an agreement. Sutro believed he had permission to build the railway through the cemetery plot once he paid to move twelve bodies buried there. The Knights of Pythias thought Sutro would pay $250 to move each body, while Sutro originally offered $150 a piece. But in later negotiations, Sutro offered $5 to move each of the bodies, and the Knights of Pythias refused.

At this point, Sutro became furious, accused the fraternal organization of trying to blackmail him and said he would build the railroad through the graves “without asking anybody’s leave.” By the time local judge issued an injunction on the work, Sutro’s workers had torn down cemetery fences and laid tracks right on top of several graves. “Considerable tilling” had been done over them, and there was “no attempt made to carry out the original arrangement to move the bodies.” The tracks also ran close to the tombstones of other graves.

Sutro’s engineers claimed that there were no graves under the railway and that the land in question had been “allowed to fall into decay.” He accused the Knights of Pythias again of trying to “scotch the old man for a few dollars.” He told the San Francisco Call, “The work is done and the restraining order is of no effect. There will be no trouble, as the whole thing is over.” A Call reporter noted that defacing, breaking or removing tombs was a violation of the penal code, but Sutro wasn’t prosecuted for it.

Photo by Mathew Brady, United States Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Adolph Sutro, 1850.

It wasn’t Sutro’s only run-in with the law. On a late September morning in 1889, two members of San Francisco’s Health and Police Committee visited City Cemetery and discovered that Sutro had inexplicably enclosed 160 acres of the cemetery with a fence. He had rented the land for several years for use as a pasture for his animals, but the fence was built without permission, and the board of supervisors ordered him to remove it. A few days later, the city sent a surveyor to establish the correct boundary lines.

Sutro tried to put his own spin on the situation, sending his agent, Alexander Watson, to tell officials that “there are but 200 acres of land in the cemetery, and that if Mr. Sutro had taken up 160 acres only forty would be left, which is absurd,” the Call summarized. Watson said Sutro had had his land surveyed and was well aware of where the boundaries were, insisting that the city was the confused party. “The charge of the Superintendent of the cemetery that Mr. Sutro has absorbed any of the city’s land, Mr. Watson claims, was caused by that official’s ignorance of where the lines really run.”

Despite his claims that he meant the cemetery no harm, Sutro’s actions tell a different story. In February 1891, he invited a number of local and federal dignitaries for a visit. His guests that day included San Francisco mayor George Henry Sanderson, several members of the city’s board of supervisors, two park commissioners, U.S. Army major general John Gibbon and Colonel George Mendell, chief of the Engineering Corps of the Division of the Pacific. He wanted to show them a two-hundred-acre area of San Francisco, some of which belonged to City Cemetery, because the military hoped to build defensive fortifications along the San Francisco coastline.

“The Government is anxious to secure as much of the tract as possible, but will not pay a fancy price. It has been suggested that the Government give the city a part of the Presidio Reservation in exchange for the cemetery tract,” the Daily Alta California reported.

But that wasn’t the only reason Sutro invited everyone out to the cemetery. He urged his guests from the federal government, Mendell in particular, to begin the process of condemning the entire cemetery. Mendell said he had the authority to condemn fifty-five acres of it but wanted to see how San Francisco residents felt before exercising that authority.

“Nearly all present expressed an opinion in regard to the matter, and the general impression seemed to be that it would be to the best interests of the city to permit the Government to condemn the cemetery. Then the city would be rid of an eye-sore, adequate protection would be obtained for the harbor of San Francisco, and with the money the city could purchase a cemetery outside of the city and pay for the removal of the bodies now in the City Cemetery,” the Alta reported. It’s no surprise that Sutro’s elite and powerful guests felt this way. None of them represented the indigent, Chinese or other local societies whose people were buried there. They didn’t see it as sacred ground, just an “eye-sore.”

The same day all those dignitaries visited Sutro, a San Francisco Examiner reporter trekked out to the cemetery to describe its current state. The article depicted the sharp divide between those with resources and those without—“Desolate and Forsaken,” the headline read. While some areas were evidently well tended, including the Jewish and Chinese sections, others appeared “uncared for and seemingly forgotten,” the reporter wrote.

Here lie the city’s pauper dead. The dry grass tangles thick and long, and here and there are bunches of scraggly brush—skeletons of dead bushes. But there is not a tree in the whole place. Not a slender fir tree, and not a bit of green vine or growing twig. The neglected graves stretch out row after row. At the head of each was once a board numbered with the number of its silent owner. There are no names upon these headboards, and wind and weather have worked hard to obliterate even this simple mark of identity. Many of the numbers are illegible.

It was written as if to support Sutro’s proposal to condemn the cemetery. And once Sutro had Mendell’s commitment, he didn’t waste any time. By mid-February 1891, he was before the board of directors of the Real Estate Exchange, telling them that the U.S. government should condemn City Cemetery and pay the city for the fifty-five acres needed to build harbor defenses; he suggested the rest of the land should be turned into a city park.

That’s essentially what happened. The U.S. government bought fifty-four acres in 1891 and turned them into Fort Miley, a coastal fortification that included a battery for rifled guns and another for twelve-inch mortars, as well as barracks and other buildings.229 Sutro became San Francisco’s mayor in 1895, and in January 1896, he signed an order barring San Francisco’s cemeteries, including City Cemetery, from selling any more lots for future burials. Property owners in the Richmond District—the same ones who were behind efforts to oust the cemeteries on Lone Mountain—helped get the ordinance introduced and passed.

It was the beginning of the end for San Francisco’s burial grounds. The move blocked local cemeteries from earning revenues, and the San Francisco Call predicted that the cemetery associations would sue. They did.

Cemetery associations argued that the ordinance didn’t do anything to prevent burials, since there was room for eighty thousand more graves in lots that were already sold. On top of that, they said it wouldn’t affect City Cemetery at all, because the lots there weren’t for sale.

After signing the ordinance, Sutro said it was only a matter of time before the cemeteries were removed, given how densely populated the western neighborhoods of San Francisco had become. And he agreed with locals who said the cemeteries were bad for people’s health.

Any authority on sanitation will tell you that cemeteries cannot avoid being a menace to the health and lives of the cities in which they are allowed to exist. The rain soaking through the ground gets into the water supply and is bound to poison it. The air, too, is laden with deadly gasses that are detrimental to health, and in the case of San Francisco the danger is particularly great owing to the fact that the prevailing winds for the larger portion of the year blow directly into the populous City.

Sutro served a two-year term as San Francisco’s mayor, from 1895 to 1897. He died of unknown causes in August 1898, although his family said he’d been in mental decline for almost a year before his death. He didn’t live to see the removal of the cemeteries he hated so much. In one final irony, Sutro’s body was cremated, and his ashes were buried on his Sutro Heights estate next door to City Cemetery.

Photo courtesy of Beth Winegarner.

The inscription on the Ladies’ Seaman’s Friends Society monument.

The End of the Cemetery

By 1893, 18,000 people were buried in City Cemetery, and when San Francisco ultimately banned burials in the early 1900s, the cemetery held about 20,000 graves. Through its years as a cemetery, though, City Cemetery welcomed as many as 28,000 to 29,000 burials, including the graves of more than 6,300 Chinese residents whose bones were eventually returned to China.

A decade after Sutro’s death, in December 1908, the city’s health committee asked the board of supervisors to order removal of the graves at City Cemetery. The city sent notices to fraternal and other organizations that held plots to let them know eviction was on the horizon. However, city officials didn’t bother to disinter and relocate the indigent dead who’d been buried there on the city’s dime, and many of the other remains buried at City Cemetery had nobody to claim them. While San Francisco’s other cemeteries at least made an effort to move their graves to new burial grounds in Colma, City Cemetery made little effort on behalf of its dead.

Also in December 1908, San Francisco coroner Thomas Leland and Supervisor Henry Payot visited City Cemetery to investigate reports that many of the graves had become exposed and desecrated. A massive slab covering the tomb of a Russian woman named Mary Gribbish had been broken and pried away, leaving her expensive clothes and jewelry vulnerable to robbery. Vandals had dumped rubbish on other exposed graves.

A year later, in December 1909, the city officially dedicated City Cemetery lands for “the most picturesque park in the world.” The new park would rest on two hundred acres of coastal land, including the City Cemetery and adjacent property, bounded by Thirty-Third Avenue, Clement Street, Baker Beach and the line of West Clay Street, if it had continued through the park. The San Francisco Call claimed that the cemetery had been closed for twenty years (it had only been eight), and yet the burials still needed to be moved. Once that happened, “the improvement of the park with drives, walks, benches and other conveniences, including lawns and flower beds, can easily be accomplished.” Instead, those improvements went forward on top of thousands of now-unmarked graves.

City leaders named the new park after President Abraham Lincoln, partly because it was near the western end of the Lincoln Highway, the first highway that ran all the way across the United States. But plans to turn the land into a public park quickly changed direction. As early as 1902, golfers had established a small golf course on the site, which was expanded to have fourteen holes by 1914 and a full eighteen holes by 1917, sprawling across the graveyard. Lincoln Park Golf Course was the first public golf course in San Francisco and one of the first in the western United States, meaning it’s open to the public without requiring membership to a country club or other private organization. It’s also open to park goers and hikers, but they’re warned to stay off the course and to watch out for flying golf balls.

Historians aren’t certain how many graves remain at City Cemetery. Researcher Alex Ryder, who conducted an extensive tally of the cemetery’s burials and disinterments, believes it’s at least ten thousand but is probably closer to twenty thousand or more.

In December 1921, as crews began excavating to build the Palace of the Legion of Honor, the forgotten dead began to make themselves known. The museum was funded by Alma de Bretteville Spreckels and her husband, Adolph, who made his money through sugar plantations and breeding racehorses, and it was intended as a memorial to California soldiers killed in World War I. When workers broke ground on the new project, they tore open 1,500 graves in the indigent section.

Genthe photograph collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

The Legion of Honor Museum in 1927, just a few years after it opened.

“The site of the $250,000 memorial to the dead was once a cemetery. It still is, but the bones are now scattered. In the excavation work for the memorial workmen have uncovered about 1500 skeleton-filled coffins,” reporter Vid Larsen wrote for the Daily News. “No provision was made for the reburying of the bodies. Workmen have cut down about nine or 10 feet in their work. Sometimes as many as four or five bodies have been pulled out in an hour.”

Larsen and a colleague visited the site and reported seeing “piles of bones not completely covered by the dirt,” many coffins cut in half by the teeth of excavating machines and more coffins poking out from the soil along the bluff. Someone made off with thirty-five dollars from one coffin, and someone else found an expensive ring in another. Local colleges bought some of the skulls. The foreman told the reporters that his crews refused to touch the bones, saying, “The only thing we can do is to scrape them over and cover them up again.”

C.W. Eastin, an attorney representing the plot holders, told the Daily News the next day that the actions of Legion of Honor crews were a violation of the same laws Adolph Sutro flouted decades earlier. “Section 290 of the penal code says: Every person who mutilates, disinters or removes from the place of sepulchre the dead body of a human being without authority of the law, is guilty of a felony,” Eastin told the newspaper. He added that “there is grave doubt that building a war memorial or even the public golf links at Lincoln park is legal.” But his protests failed to stop the construction.

The Palace of the Legion of Honor was opened to the public on Armistice Day, November 11, 1924. The graves beneath it remained relatively undisturbed until 1993, when a new round of excavations at the museum uncovered what archaeologist Miley Holman called a “charnel heap,” a mass grave likely left over from the 1921 reburials. The remains belonged mostly to working-class white people who were buried in redwood coffins. Their bones showed fractures, skeletal trauma, arthritis and other signs of the heavy labor they’d performed in life. Some of the bones bore signs of medical experimentation after death. Even in 1993, the museumʼs officials and builders didn’t want to deal with the work of processing the remains; Museum Director Harry Parker complained to the San Francisco Chronicle that the delays associated with the discovery would cost $50,000 a month. Ultimately, the Legion of Honor Museum turned the remains of about 900 early San Franciscans over to the medical examiner’s office, and they were reinterred in Skylawn Memorial Park in Colma. The rest, however, are still beneath and around the museum, where more than 170,000 patrons visited in 2021.

“These are already the bodies that no one wants; immigrants, poor people, religious minorities. It gets clearer by the minute that the city still doesn’t fucking want them. To this day, the bodies of the men and women who built this city lie anonymously under a golf course and museum,” writes Courtney Minick, the creator of Here Lies a Story. She argues that City Cemetery isn’t a former cemetery—it’s a current one.

In recent years, City Cemetery’s legacy has attracted the attention of historians and city leaders, particularly those in Chinese communities around San Francisco. After urging from those leaders, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors granted the site landmark status in October 2022, recognizing the site’s history as a graveyard for the city’s immigrant and indigent dead.

Chinese community members gathered at the Kong Chow monument for the autumn festival of Chung Yeung in 2021 and 2022, bringing offerings of incense, paper money and food for the ancestors. It was probably the first time in more than a century that Chinese locals commemorated the dead at City Cemetery. “Li Dianbang, director of the Historical and Cultural Relics Committee of the CCBA, remarked that commemorating the Kong Chow structure could help with the current prevalence of hate crimes against Asian communities because ‘[a]ll ethnic groups must know each other’s history and respect each other’s contributions to this land,’” city archaeologist Kari Hervey-Lentz wrote. Those who visit the site now may discover fresh flowers on the altar and a broom for sweeping out the Kong Chow structure, acts meant to honor the dead.

“This place has been a resting place for our earlier immigrants.…Many of them did not go home, and they made America their home,” said Larry Yee, president of the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association. “And they buried their bones here, in America. “

Excerpt from San Francisco’s Forgotten Cemeteries: A Buried History by Beth Winegarner published with permission from The History Press.

September 3, 2025

Dead Strangers and Other Friends

Bereaved families come to councils as their last resort, often ashamed, their grief compounded by feelings of having failed their loved one by not giving them a ‘proper’ funeral. The ‘pauper’s funeral’ terminology of old doesn’t help. Giving rise as it does to anxiety around what the service will look and feel like. This anxiety is partially justified as there is something of a postcode lottery in terms of service length, or even of having one altogether. Thankfully my council understands the importance of the ritual, providing a fifteen minute slot with a celebrant, and this goes some way to restoring a feeling of peace and dignity. I then spend the duration of the case walking the ever-shifting line between official, grief counsellor and friend, spending many hours of my own time chatting and texting. Never picking up the phone to relay information without first asking how the person is doing and then actually listening.

But we’re getting too touchy feely, we are meant to be at the business end. You see how this job gets blurry, right? So, returning to my initial phone call, I will take as many details about the deceased as are readily available, this ranges from a lot in the case of family and care homes to sometimes zero in the case of police and coroner referrals. I will then drop everything else I am working on, as time is of the essence, and carry out some or all of the following tasks, depending on the case type. Instruct our funeral director to collect the body, go to their GP surgery to get their medical cause of death certificate, or phone the coroner to get the order for burial or cremation form, pick up their house keys from the police, visit our funeral director to schedule the date and sign the order, and then book myself a slot to register their demise.

To do this last bit I have to go to the online registration system where I am given the choice of either ‘make a birth appointment’ or ‘make a death appointment’. Truly the circle of life. Making a death appointment grimly amused me at first, sounding as it did, like I was arranging a meeting with the actual grim reaper to complete the admin side of dying in his office. I stood up at my desk as I put my coat on to leave for my first ever registrar meeting and dramatically announced ‘I must go, I have an appointment,’ pause for effect, ‘with death.’ Putting the fun in funerals there. Of course, it’s nothing as exciting as that and I simply collect the piece of paper which marks their official end, the death certificate. There are so many death certificates out there with my name on and giving my relationship to the deceased as ‘causing the body to be burned/buried’ that future historians searching local records will probably be wondering about me.

In between all of these appointments I will visit the deceased’s residence and, in the case of those without family, carry out a house search with a view to finding any next of kin. They’re usually hiding in address books, phone logs, a scrawled email address inside last year’s balled-up Christmas card. They can also be extra hidden under years of hoarding or detritus. And sometimes just not there at all. In the absence of any immediate clues – hardly anyone has address books anymore and phones are so often pin-locked – I’ll try knocking up the neighbours. And then if I find nothing, or I find something but none of the numbers lead anywhere and the emails bounce back, well, this is where things should end. There’s nobody. Book the funeral, attend solo, and get back to work.

But whether it’s through empathy, stockpiling karma, general nosiness, or a combo of all three, I can’t let it end there. They must have been loved by someone or at the very least known to someone. And even if they somehow weren’t, I can’t just let them disappear. They deserve their decent farewell, their final summing up. So I also look out for clues as to exactly who they were, to help the celebrant tailor their funeral, and also because I genuinely want to know.

On top of looking for the usual wallets, bills, wills, bank statements with which to close down their life, I’m also looking for membership cards, letters, photos, diaries, evidence of hobbies, cd collections, signs of a religion and therefore preference for burial or burning. Any information to help me find, if not family, then friends, acquaintances, talents, ambitions, dreams, loves, lost loves: their life.

After I have taken a whistle-stop journey through their entire existence, I return to my public health duties and take their last ever meter readings, dispose of all perishable food, turn off the fridge and put their bin out one last time. Basically a cross between a private detective and a cleaning lady.

Then I take my evidence bag back to the office where I empty the person’s life out onto my desk, flanked on all sides by similar desks taken up with the contrasting workaday admin that I would otherwise be doing if someone hadn’t gone and died. Taxi plates being produced, premises licences being varied, someone taking a call about barking dogs, smelly drains, bonfire smoke, and of course the background buzz of people chatting away, most likely about Housing using our milk and tea bags again.

I put the papers in order – utility bills in one pile, bank statements in another, then credit cards, insurances, investments, pensions. I put the personal stuff to one side, as I’m going to start with the administrative things as a warm-up to the hard, human bit. I tell the DWP, I freeze their bank accounts, cancel cards, I listen to a whole lot of terrible hold music. In the case of credit card companies in particular I say ‘something else’ over and over again to a robot voice until it finally stops offering me unsuitable options and puts me through to a human. You can pay, you can transfer a balance, you can do anything, except die. I mean, why would you want to go and do that? If you’re reading this, please do better, guys. Add a deceased account holder option early on.

“But whether it’s through empathy, stockpiling karma, general nosiness, or a combo of all three, I can’t let it end there. They must have been loved by someone or at the very least known to someone. And even if they somehow weren’t, I can’t just let them dis appear.”

I don’t need to, but I go through their wallet and inform libraries, clubs, their store loyalty cards, so that the mailings cease and don’t distress anyone, or waste paper if there’s nobody around to distress. Fun fact, some stores let you bequeath points, I bestowed one chap’s Clubcard balance to his brother-in-law. Then it’s on to the strange task of calling random numbers in mobile phones and address books to inform whoever picks up of the death. It’s daunting, because it could be a bemused plumber who did one job for them in 2014, or it could be the love of their life. You have to get very comfortable very quickly with being on the phone to people who are in shock and in tears. And often due to the nature of my cases, wracked with guilt. From the estranged family member who let things slide and is trying to justify themselves to me entirely unprompted, to the best friend who argued with them when last they spoke and kept asking me if I thought that’s why they had committed suicide.

As I said earlier, if no family is found, it’s over. But as I also said earlier, it’s not over for me. If the phone calls don’t pay off I will start trawling Facebook, Twitter, posting on local group pages and forums, using the personal clues I picked up in the house like a photo outside a pub, shop, cricket club, to track someone who knew them.

Sometimes it just comes down to desperate Googling of their name. It’s amazing what you can turn up. One guy had an online tea shop and a section called ‘The Old Tea Boy’ which gave a run down of his entire life from his childhood in Ceylon, to his time as one of the youngest Brooke Bond trainees, driving around in the old fashioned red van, to his international tea-tasting career, covering every continent; all in his own chatty charming voice. A surreal experience, communing with the dead this way, but a warming one. By the way, I do this latter round of research on my lunch hour and then after-hours on my own time, as I am only paid to do the basic due diligence, and those taxi plates aren’t going to make themselves; so at ease, taxpayer.

By the time the funeral arrives, my brief but intense immersion in the person’s world causes me to feel as though I’ve met them and am attending myself as a friend. Indeed, when I was describing a couple of cases to someone recently they stopped me mid-sentence to say, ‘it’s like you know them and can see them in front of you’. True, I may never have met them whilst living, but their life and personality crystallized before my eyes during the carrying out of my basic duties, and my self-appointed ones too. Dead strangers are just friends you haven’t met yet, that’s what I say. I don’t really.

Published with permission from Mirror Books from Ashes to Admin: Tales from the Caseload of a Council Funeral Officer by Evie King.

January 6, 2025

The Story of the Unclaimed

The story of the unclaimed is, urgently, a story for today. In the first decades of the twenty-first century, an estimated 2 to 4 percent of the 2.8 million people who died every year in the United States went unclaimed—up to 114,000 Americans. This is roughly how many Americans die annually from diabetes. And that number is increasing. In Los Angeles County, the most populous county in the United States, the unclaimed used to make up 1.2 percent of adult deaths. That number inched up to 3 percent by the turn of the century—and it has continued to rise. The increase means that hundreds more residents every year end up in the Boyle Heights mass grave. In Maryland, one of the few states to keep track of unclaimed deaths over time, the percentage of people going unclaimed, adults and infants, has more than doubled in twenty years, from 2.1 percent of total deaths in 2000 to 4.5 percent in 2021.

COVID-19 made things worse. Medical examiners and coroners estimate that the number of people going unclaimed rose nationwide during the pandemic, resulting in as many as 148,000 unclaimed deaths each year. An investigation in Arizona’s Maricopa County, the fourth-largest county in the United States, revealed a 30 percent spike. Reports streamed in from across the country, underscoring the problem. The Chicago medical examiner’s office cremated twice as many unclaimed bodies in a three-month period in 2020 as in the entire previous year. Montcalm County in Michigan saw a 620 percent increase in unclaimed bodies in 2020. In Fulton County, Georgia, officials oversaw burials for 456 unclaimed bodies in 2021, 150 more than in previous years. In Hinds County, Mississippi, the coroner commandeered a refrigerator truck to store unclaimed bodies after the number ballooned.

Los Angeles County Department of Health Services

A 2020 headstone marks the communal grave where the remains of 1,900 people were laid to rest during the Ceremony of the Unclaimed Dead in Los Angeles.

There is no federal agency to track or oversee the unclaimed, just a patchwork of ad hoc local practices. In smaller cities and towns, burials for the unclaimed happen, if they happen at all, randomly. Ashes can languish for years in the desk drawer or office closet of a local county sheriff or wind up abandoned in private funeral homes.

The unclaimed mostly go uncounted and unseen. Megan Smolenyak is a genealogist and founder of Unclaimed Persons, a web-based group of more than four hundred genealogists who volunteer their sleuthing skills to resource-strapped forensic communities across the country. They locate kin when government employees cannot. Smolenyak describes the rising numbers of unclaimed as its own “quiet epidemic.”

This book grew out of our efforts to unravel the mystery of the unclaimed: Who are they? And why do they end up where they do? We follow four individuals who died between 2012 and 2019—some destitute and some with means, some with close relatives, some without—as they wend their way through L.A. County’s death bureaucracy. To piece together the story, we observed the work of county employees who care for the unclaimed: those who field phone calls from concerned neighbors, those who go into homes and hospitals to retrieve bodies, those who call families to try to compel them to claim, and those who divvy up the dead’s assets.

As we immersed ourselves in this world, the book morphed into a quest to better understand what we owe one another in death and in life. The unclaimed raise pressing existential questions: If you die and no one mourns you, did your life have meaning? If a common grave can now be the final destination for anyone, rich or poor, what does that say about us? What does it say about America? The answers we found were daunting and, at times, disheartening. The unclaimed bring today’s fractured families into sharp focus.

And yet, we found hope. Los Angeles, a city mocked around the world for being fickle and vain, points the way. Far from the glitter of Hollywood and ostentation of Rodeo Drive, nestled in quiet pockets of the county, some Angelenos have devoted their lives to making sure that the unclaimed are not forgotten. These citizens who have taken it upon themselves to care for the dead receive no money and few accolades. But they feel a moral responsibility to step in where traditional families have failed—creating new kinds of kinship, rebuilding local communities, and caring for the most overlooked, even in death.

Excerpted from The Unclaimed: Abandonment and Hope in the City of Angels by Pamela Prickett and Stefan Timmermans. Published with permission from Penguin Random House LLC.

September 10, 2024

Memento Mori: Remember You Will Die

A memento mori—Latin for “remember you will die”—is a practice, object, or artwork created to remind us that we will die, and that our death could come a at any moment. By evoking a visceral awareness of the brevity of our lives, it was meant to help us remember to make choices in line with our true values. The use of memento mori, which seems so counterintuitive today, is a practice that was found in cultures all around the world and for many millennia; it even lives on today.

Memento mori were a part of life in ancient Egypt, where dried skeletons were sometimes paraded into a feast at its height to remind the revelers of the brevity of life. They were also frequently encountered in ancient Rome, where it was common to see skeleton mosaics on the floors of dining rooms and drinking halls. And, if you attended a feast, you might be gifted with a tiny bronze skeleton called a larva convivialis, or banquet ghost. In both cases, these memento mori were meant to ex- press the well-known Latin adage carpe diem—meaning “seize the day”—reminding viewers to eat, drink, and be merry, for tomorrow they might be gone.

Socrates, the ancient Greek founder of the Western philosophical tradition, asserted that a memento mori–like contemplation of death was at the core of the practice of philosophy. “The one aim of those who practice philosophy in the proper manner,” Plato records him as saying, “is to practice for dying and death.” Similarly, the Stoics, a philosophical school in ancient Greece and Rome, believed that one must contemplate one’s own death as a means toward living more fully and authentically. Seneca, a prominent Stoic philosopher, urged his readers to rehearse and prepare for death as a means of diminishing their fear.

Memento mori also play an important part in Buddhist practice. In the Buddha’s own time, there was a practice called the Nine Cemetery Contemplations, in which practitioners were encouraged to visit the charnel grounds—where bodies were left, aboveground, to be eaten by vultures or to decompose—in order to meditate on corpses in different states of decomposition. This was meant to help people overcome fear of death and release attachment to the body. This tradition even extends to artwork, in the Japanese tradition of kusözu, which are paintings that artfully depict these nine stages of a decaying corpse. Even today, it is not uncommon to find a human skeleton in places devoted to Buddhist meditation.

Skull in a case: memento mori, ca. 1650, Albert Jansz. Vinckenbrinck, at Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Christianity also makes use of the memento mori. In this tradition, it is meant to remind one to live a pious life, to resist earthly pleasures and temptations so that one will be ready to meet—and be judged by—God. Much as in the Buddhist tradition, Christians were, at one time, encouraged to meditate upon the dying and decomposing human body. Death was also, in the medieval era, brought to mind by the daily recitation of prayers called the Office of the Dead, which were supposed to prepare one’s soul for death and the Last Judgment. And, of course, every year on Ash Wednesday, devotees go to church, where the priest renders a cross in ash on their foreheads, a visceral reminder that from dust we are formed, and to dust we shall return.

In the Christian tradition, memento mori could also take the form of jewelry, including skull rings—often distributed as funeral souvenirs—and intricately carved rosary beads. Memento mori imagery was also commonly used in watches and clocks, playing on the close association between the ideas of time and death. Gravestone art regularly featured winged skulls or skulls and crossbones, and some grave markers—such as the lavishly carved tomb sculptures known as transi—even depicted the deceased in the form of a decaying cadaver.

Skeleton alarm clock (1840-1900), Science Museum, London / Science & Society Picture Library

There were also a number of fine art genres that brought memento mori imagery into everyday life. One of these was the vanitas (literally “vanity”) oil paintings, which featured imagery such as skulls and snuffed-out candles, symbolizing a life cut short. These were hung in the home to encourage the viewer to focus on the eternal, rather than the momentary pleasures of life on earth. Another popular genre was the triumph of death, in which an anthropomorphized figure of death plows down everything in its path, giving vision to the idea of death as an arbitrary and unstoppable destructive force. There is also the danse macabre, or “dance of death.” Popular at a time when the black plague was decimating Europe, these works also feature an anthropomorphized figure of death, this time merrily leading people of every age and social station—from queen to pauper to child—in a dance to the grave. This allegory points to the fact that death makes no distinctions; to death, we are all equal.

Memento mori could even take the form of actual human remains. To this end, wealthy gentlemen often displayed a human skull in their library or cabinet of curiosities as a poignant reminder of the brevity of life. And cemeteries—in a time before permanent interment— would dig up defleshed skeletons and exhibit the bones, frequently in artistic arrangements, to remind the visitor of their own death.

A contemporary manifestation of memento mori can be found to- day in New Orleans’s Mardi Gras, as part of the festivities of the Black Masking Indian krewe. Their annual procession begins at dawn when the so-called Skull and Bones Gang—dressed as skeletons—knock on the doors of neighborhood homes to remind them of the transience of life and invite them to join the festivities. In a similar vein, Tibetan Buddhist festivals often incorporate so-called cham dances. These are devotional performances that often feature costumed skeletons intended to remind revelers of the presence of death.

Tibetan skeleton dancers, 1925

A fun and surprising modern manifestation of memento mori is a smartphone app called WeCroak. The app—inspired by a Bhutanese proverb asserting that the key to happiness is contemplating death five times daily—sends you several thoughtful quotations related to mortality throughout the day. In the words of the app’s official text: “Contemplating mortality helps spur needed change, accept what we must, let go of things that don’t matter and honor things that do.”

Far from morbid, contemplating death in this way is the best method I’ve found for revealing, with clarity, what it is we really value. I have also found no better tool for inspiring us with the will and courage to make the changes necessary to live a life that is true to ourselves and in accord with our real values; one that will, or so we can hope, leave us with the fewest deathbed regrets.

From MEMENTO MORI: The Art of Contemplating Death to Live a Better Life by Joanna Ebenstein, published by Avery, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2024 by Joanna Ebenstein. MEMENTO MORI is available now, purchase online, or from your favorite local bookseller.

June 27, 2024

Rally Around the Flag: How the Death of an Irish Setter Taught a Lesson to a Nation

Note from the author:

As exciting as writing a book on a subject you care passionately about can be, there is an aspect that is heartbreaking: the reality of word counts and editorial constraints inevitably means that there are some stories you have come to love which wind up being cut. I have a book on pet cemeteries and animal burials coming in the Fall, titled “Faithful Unto Death”, and in the last round of editing the situation was put to me bluntly. Something has to go. To fit all the photos we’re using and make our word count within the number of pages at our disposal, we need to cut the equivalent of about one story. That is why what follows, the tale of the death of an Irish Setter named Garry, will not appear in the book. But it is, and I hope you will agree, a wonderful and historically important story, one which I think still has something to teach us even a century later. This is why, with thanks to the Order of the Good Death, it is offered to you here. And for those curious about what is in fact in the book, here is a link.

Small, private pet cemeteries had a heyday in the United States in the late nineteenth through early twentieth centuries. This was before urban pet cemeteries had become popular, and since owning sufficient land was the first necessity for being able to start a cemetery, it should be no surprise that they were primarily found on the estates of wealthy people. Among the most noteworthy was located in a clearing of trees on Mackworth Island, in Casco Bay just off the coast of Portland, Maine. The island had been owned by the Baxter family, which gained its wealth from the canning and packing of vegetables. In a small clearing set just back from the island’s coast, Percival Proctor Baxter, who would become the fifty-third governor of Maine, would establish in his youth an animal cemetery.

The site is marked by a simple stone circle, and the paucity of visible memorials—there are only a few cracked gravestones—no doubt causes most visitors to pass by without giving it much thought, and certainly without recognizing its extent. In fact, there are many more burials here than are initially apparent. Rather than being individually marked, they are recorded on a bronze plaque attached to a large boulder within the circle. “To my Irish setters/life long friends and companions/affectionate faithful and loyal/Percival P. Baxter/Governor of Maine,” the inscription reads, and then notes those interred at this spot. And it is one of those names that gives the cemetery its importance: a scandal surrounding the death of Garry on June 1, 1923, turned him into one of the most influential dogs in American history.

Paul Koudounaris

It was not Garry’s death itself that was scandalous, as he had died of old age and its related complications. Nor had there been any hint of impending controversy during his life, as he had always been a good dog who would have been content to remain far removed from the public eye had not his owner been the state’s governor. The hubbub was instead due to Baxter’s act on the death of his faithful companion. On his authority, an order was issued to lower the American flag at the statehouse in Augusta to half mast in Garry’s honor. Lowering the American flag is reserved for times of national tragedy. It is a gesture not to be taken lightly, and provoked a vitriolic response quickly followed.

Many of the state’s political observers had already questioned whether Garry hadn’t gotten privileges enough, including many not extended to the state’s own citizens. The dog could come and go as he liked from the Capitol Building, for instance, whereas human visitors by law had to register before entering. He even had access to areas where outsiders were not allowed, such as the Treasurer’s Office. In the governor’s chambers, meanwhile, Garry had his own couch, and was allowed to sit in on councils in which Baxter confirmed appointments and voted on pardons—there were even whispers that the dog’s attitude towards a petitioner might be the deciding factor when it came to such decisions.

The Bee, Friday, June 8, 1923.

And now Baxter had ordered the American flag to half mast at the dog’s passing? The consensus was that this time the man had gone too far. No matter how much he had been affected by the loss of Garry, he had abused his authority and mocked a solemn gesture. The condemnations came quickly, led by members of the American Legion and other veteran’s groups. Colonel George R. Gay, an official with the local chapter of the Grand Army of the Republic, lodged an official complaint with the State House on behalf of his post. He likened the act to a form sacrilege, one that insulted every member of his organization. While he loved dogs himself, Gay explained, the problem had nothing to do with canines in general. What he and his fellow soldiers loved most of all was “the old flag which so many of them gave their lives to preserve,” and it should not be lowered for vain or personal reasons. (2)

Mrs. William Wolff Smith, Chair of the Correct Usage of the American Flag Committee of the Women’s American Legion in Washington, D.C., pointed out that, strictly speaking, Garry wasn’t even a citizen. Had “the dog been an American citizen it might be different,” she commented, “but he was no more of a citizen than a strawberry patch.” Baxter’s political opponents had meanwhile pounced on the incident, vowing to use it against him. Word quickly spread, and by the next day people as far away as the West Coast heard about the governor’s act, and suddenly everyone was taking shots at Percival Baxter.

And that was fine by him. To understand why, it will help to know a bit more about the man. Despite coming from a politically prominent family, his father having served as mayor of the state’s most populous city, Portland, he was definitely not a standard, party-groomed politician. A Republican who had previously served in both Maine’s House of Representatives and Senate before assuming the office of governor in 1921, many of his views would even now seem progressive, and he was not afraid to take a stand in the name of causes he believed in, even if the result was a ruckus.

The Hartford Courant, Saturday, June 2, 1923.

Baxter was, for instance, among the first prominent politicians to publicly oppose the Klu Klux Klan, which had at that time gained a strong foothold in Maine politics. He was also a prominent supporter of environmental causes, and as both a legislator and governor he campaigned to get the state to purchase the land around Mount Katahdin, the tallest peak in Maine, in order to preserve the area as a wilderness park. When he failed to sway the state, he instead used his own money to buy up the land and donate it. This gift earned him the nickname “the man who gave away mountains,” and the land is now known as Baxter State Park, one of the largest on the East Coast.

But his greatest interest was animal welfare. A framed placard reading “Be Kind to Animals” stood in his office between the national and state flags. He did not hunt, unusual for the time, having abandoned the pastime for ethical reasons. “I would no sooner think of killing a deer than I would step out and shoot some down faithful old horse out there in the street,” (4) he said. He also took an active stance against the fur trade, and as governor scuttled a plan to provide a fur farm at the University of Maine. Likewise, he declined a request to capture local bear cubs and send them to a zoo in Massachusetts, commenting that, “our wild animals are entitled to their freedom, and, unless they are dangerous to human life and property, should not be molested.” (5)

A pamphlet authored by Baxter and issued by the state urged people to treat animals humanely. “They work for, depend upon, and are devoted to us,” he explained, and “On our part we always should care for them, protect them against all neglect and cruelty and do everything in our power to right their wrongs.” He pleaded with his readers that “should you see animals or birds being abused, do all you can to stop the abuse; and you yourselves should never fail to treat them kindly.” (6) Likewise active in the anti-vivisection movement, Baxter worked during his tenure as governor to prevent the cruel use of animals for dissections in Maine’s schools. All of this considered, it is hardly a surprise that he was lauded as “America’s greatest humane governor” by the New England Anti-Vivisection Society.

Among all animals, Baxter’s greatest joy was dogs, and of all breeds, his favorite was the Irish setter. Garry was not his first. Baxter’s history with them dated back to his childhood in the 1880s, when he received as a gift from his father an Irish setter puppy named Glencora, who would test the boy’s heart from the outset. The puppy was frightened and confused that first night and began to cry, and as young Percival lay in bed worrying about his new friend and wondering what to do, someone in the house got up and took care of the situation—by putting the dog out. “This cruelty was more than I could stand,” Baxter later recalled, and he snuck out, found the frightened puppy huddled in the yard, and carried her upstairs and placed her in his own bed. (7) The scene repeated itself for several nights until the dog was finally enough at peace to sleep quietly in the house.

Maine Governor Percival Proctor Baxter with his Irish Setter, Garry.

Baxter eventually began breeding Glencora. Her puppies were sent to good homes for a nominal fee, but he also kept a few for himself and continued breeding them. The Irish setters became a constant motif in his life, there always seemed to be one around and the love he had for these dogs was so sincere that people didn’t seem put off, despite the liberality with which he treated them. Not even after one of them, Deke, who lived on campus with Baxter during his university days at Bowdoin College, carried a large bone into the university chapel during a service and laid it down at the feet of the school’s president during prayer. In the end, he raised an estimated five dozen Irish setter pups, all descended from the first, Garry among them. But now, with the flag at half mast, Baxter had finally crossed the line of public decency.

What the people lodging complaints didn’t know was that the lowering of the flag was a carefully contrived gesture designed to manipulate them into the exact situation they were in. Garry had been sick for some time, and after the best veterinarians in New England failed to suggest an adequate plan of treatment, the governor resigned himself to the fact that his friend’s passing was imminent. He then came up with a plan to turn the tragedy of Garry’s death into something positive. Yes, flying the flag at half mast would raise ire, but doing so would provide an opportunity to open a public dialogue. “I did it . . . to teach a lesson,” Baxter explained to a newspaper reporter, “to draw people’s attention to the qualities of the dog, qualities which so often are forgotten in human relationships.” (8) In other words, the ruckus would provide him an audience to proselytize to about a topic he passionately believed in.

As the complaints rolled in they were met with a pamphlet, printed in advance, to be distributed to the governor’s detractors. “If all men would acquire the outstanding virtues of the dog,” it explained, “great happiness would soon be spread over this sordid world.” And of those virtues, Baxter believed that loyalty and unselfishness are the greatest.

Where can these be found in purer form than man’s best friend, the dog? He never falters in his devotion, never questions nor complains. Hunger, threat and privation to him are nothing if he can share them with his master and comfort him in his distress . . . The loyalty and unselfishness of a dog may well put most men to shame, for few are as loyal to their Heavenly Master as is the humble dog to his earthly one. (9)

There were many people who would no doubt grant him these points, but still insist that the lowering of the flag was inappropriate. And to them, Baxter explained his belief that, “when men and women of this State and nation think through what I have done, they will see (that) a lesson in the appreciation of . . . animals has been taught, and that my act heightens the significance of our flag as an emblem of human achievement that has been made possible largely through the faithful services and sacrifices of . . . animals.” (10) It was a nod not just to a single dog or canines in general, but a public recognition of all the animals that worked alongside humans to found the United States and toil for its prosperity.

And considering that selfless service, could anyone begrudge a symbolic lowering of the flag in thanks for the heretofore unacknowledged role animals played in the building the country? Baxter didn’t think so. “The fair names of our State and Nation have not been tarnished because a flag was placed at half mast out of respect to one of God’s humble but noble creatures,” he explained. And as for lowering the flag for Garry in particular, Baxter believed that the act was a “fitting tribute . . . to my dog and to dogs of ages past, a tribute well deserved, but long deferred.”

He concluded that the act didn’t diminish the flag one bit and that, personally “I should esteem it an honor when my time comes to have the same Capitol flag that was lowered for my dog lowered for me.” (12) This was entirely new and unexpected grist for the mill of public opinion. The man had a point. Animals certainly had been indispensable to the founding and prosperity of the nation, often laboring in brutal conditions. And they had never gotten their due. Was there really harm in finally offering them this token gesture of recognition?

Things turned around quickly. The governor’s gesture was suddenly deemed admirable, and messages of a different sort now arrived. “I have received probably a thousand letters and telegrams from all parts of the country. Only one was unfavorable,” he was soon able to report. (13) A school girl from Illinois, inspired by the publicity, even wrote a poem in the governor’s honor that wound up printed in humane society journals across the country. It was the work of a child to be sure, but the sentiment behind it spoke for many people considerably older than she.

Percival Proctor Baxter,

A Gentleman of Maine,

Has gained a reputation

For himself, and great fame.

I see his picture often,

But the one I like best,

Is where he has his Garry,

It’s nicer than the rest. (14)

The members of the Grand Army of the Republic, meanwhile, withdrew their condemnation and had all criticism of his actions withdrawn from their official records. They went so far as to offer him a vote of appreciation and confidence. And so that the dialogue raised upon Garry’s passing should not fade too quickly, the Governor’s Council voted a year after the dog’s death that a bronze memorial to him should be placed in the State House, so that it might serve as a “constant reminder to the people of Maine of the faithful and unselfish services rendered them by their domestic animals.” In announcing the memorial, the Council offered its hope that “the day will soon come in this State when cruelty to and neglect of animals will be no more and when man will be kind and merciful to all of God’s creatures, however humble.” (15) From what initially looked like a public relations disaster, the governor had scored a resounding victory.

Paul Koudounaris

Baxter never commented on this so we simply can’t know his intentions. But we can know a fair bit of his on his feelings about politics at the time. With his dedication to serving humble causes even at the risk of his own reputation, he seems like an awkward fit among American politicians, and he himself felt this was the case: he served a single term as governor and declined to run again when it ended in 1925. Politics, he had decided, were not for him. But dogs were. While there was no room left on the plaque on Mackworth Island, there was still room in his heart. More Irish setters were indeed to come, and when they were likewise buried in the stone circle, additional, smaller plaques had to be added to the boulder. The first notes four dogs buried through 1934, and the final small plaque names two others, through the 1940s, when the island was given over to state as a gift. Six more dogs total, and it turned out that Baxter wasn’t quite through with Garry, either. Two of those buried afterward were named in his honor, a favorite dog who in his passing helped teach the nation a lesson about its debt to animals.

Sources:

(1) It should be noted that the Garry in question was technically Garry II. But in the controversy that followed the II was dropped by the press and the dog became known then and afterward simply as Garry, and Baxter himself listed him without the II on the plaque.

(2) “Veterans Protest Honor Given Dog,” Hanover (PA) Evening Sun, June 4, 1923, 8.

(3) “The Flag Incident in Maine,” Buffalo Courier, June 8, 1923, 6.

(4) “Governor Who Honored Dog Makes Reply to His Critics,” New York Times, July 8, 1923, 7:3.

(5) Liz Soares, All for Maine: The Story of Governor Percival P. Baxter (Mt. Desert, ME: Windswept, 1995), 38.

(6) Ibid. 37-38.

(7) Ibid. 9.

(8) “My Faithful Dog Unlike My Human Friends Never Betrayed Me—Baxter,” Lewiston Evening Journal, June 5, 1923, 11.

(9) Ibid.

(10) Ibid.

(11) “Governor Defends,” Portland (ME) Evening Express and Advertiser, June 4, 1923, B9.

(12) “Defends Lowering of the Flag for Dead Dog,” Portland Press Herald, June 5, 1923, 3.

(13) “A Governor Who Put Flag at Half Mast for his Dog,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, August 24, 1923, 6.

(14) Soares 39.

(15) Ibid., 42.

June 13, 2024

Death Is Not a Dirty Word

One of the reasons we find death so frightening is that a lot of us refuse to talk about it. We’ve made it such a taboo topic, I think half of the fear we feel is just from avoiding it. Avoiding talking about it. Avoiding learning about it. If we did those things, it’d be less scary. The more willing someone is to talk about and accept the fact of their death, the better they’ll live, and the better they’ll die.

You’ve heard the way people talk about someone who’s died.

“She’s gone.”

“He’s no longer with us.”

“They passed on.”

I get it. It’s gentler. But as we think about shifting the way we look at death and dying, we also need to look at the words we use and start getting comfortable with saying the words: he’s dying, she’s dead, they died.

Death.

I understand that not everyone’s there yet. But we all can start trying it on a little bit. Try saying, “Mom died.” Try saying, “I’m dying.” Try saying those words; it’s actually really therapeutic. Plus, by using them yourself, you give others permission to use the “d-words,” too.

Specifically, I think it’s important to talk about death with the person who is dying, when they’re lucid. I see that my patients who are willing to talk about their death and what they want before they die have more peaceful lives and far more peaceful deaths. It helps their loved ones, too. Often I’ll begin, “We all have an end-of-life journey. All of us. Right now, yours is a little clearer than other people’s. So what is that going to look like?” Then I talk about death and dying. When I model doing it, the patients and their family members are usually a little more comfortable talking about it themselves.

Some people ask me, “Why is it so important for people to know that they’re going to die?” It’s a great question. When people choose to learn about their particular illness and what their death might look like, their fears often are eased as they acknowledge what’s happening. The people who are willing to discuss end-of-life issues and to accept that they’re going to die seem to carry about them a certain type of freedom, and they truly live their last days well. Their fear tends to decrease, and they tend to be freer and more full of life, even though they’re dying.

I’ve also seen the opposite. When people are unwilling to look squarely at death, the last few months of their life are usually filled with fear, anxiety, and stress. There seems to be a lot of existential suffering and chaos. That’s why I want to normalize talking about death and dying and spread the understanding that we’re all going to die.

Ria Munk on her Deathbed, Gustav Klimt

One of the reasons I’m so passionate about educating people about death and dying is because I’ve seen firsthand how our culture sanitizes the topic.

We hide it.

We embalm it.

We put makeup on it.

We photoshop it.