Caitlin Doughty's Blog, page 8

March 16, 2021

Funeral Foods From Around the World

March 1, 2021

The Rugby Team That Fell From the Sky

February 19, 2021

Have Deaths Slowed Down in Los Angeles?

February 1, 2021

Our Funeral Home is Overwhelmed With Bodies

January 21, 2021

FINE, I’ll React to Famous Film Corpses

December 22, 2020

Iconic Corpse: GRAM PARSONS

November 25, 2020

The Bubonic Plague in… San Francisco?

#MMIW: The Life and Death of Stolen Sisters

On July 3, 2017, in the Arizona portion of Diné Tribal Nation, the lands of a tribe often referred to by the exonym “Navajo,” the day was permeated by blinding sunshine and dry desert heat. Ariel Begay, a bright, witty 26-year-old Diné woman, was picked up from her family home by her boyfriend, ready to enjoy the golden days of summer; but her plans did not only extend to the simple joys of the season—Ariel had recently graduated from a medical assistant program, with the promising goal of becoming a nurse in the near future.

The next afternoon was equally ordinary, when Ariel called her mother, Jacqueline, to inform her that she would try to make it home for dinner; when she didn’t, Ariel let her family know, ending the text with her usual affectionate, humorous moniker for her loved ones—“You jerks.”

The next day, she called her cousins to notify them that she was in a town just outside the reservation with friends. Later in the day, she didn’t call her sister Valya to speak to her three-year-old nephew—which was highly unusual for her, but not enough to immediately cause alarm.

However, throughout the next few days, Ariel made no contact with family or friends, and all their texts and voicemails to her received no response.

The young woman was typically active on social media, and the absence of her lively and quick-witted personality left a deeply concerning void both online and in person.

By the fifth day, Valya began making missing person posters featuring her sister, but was held back by a feeling that she was overreacting. “She’s going to come home,” Valya remembers thinking, “When Ariel comes home, she’s going to say, ‘Why did you do this? You’re silly.”

By nightfall, Ariel’s disappearance became undeniable, and the family descended into full-blown panic. Valya put up her posters, and Jacqueline, frantic, called the police.

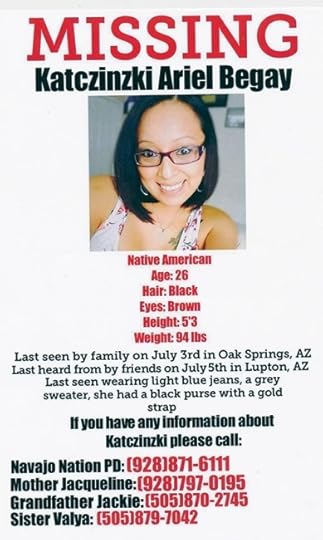

A poster seeking information on the whereabouts of Katczinzki Ariel Begay is being circulated throughout the Navajo Nation – via Navajo Times

The Diné Tribal Nation is the largest reservation in the United States. Spanning 27,000 square miles, including pieces of Arizona, Utah, and New Mexico, and home to around 170,000 Diné citizens, the reservation has its own tribal police force. As is unfortunately the case for tribal police forces across the country the Diné police force is underfunded, understaffed, and underresourced, stretched to the breaking point. The family, for better or for worse, had to turn to the FBI.

For all the powers and assets at the FBI’s disposal, it would take several months before Ariel’s remains were found beneath a bridge in Arizona. The FBI, for reasons vaguely disclosed as having to do with the investigation, withheld Ariel’s body from her family for nearly a year. Over this painful span of time, Jacqueline began the family’s practice of leaving flowers on the bridge just over the place where her daughter’s body had lain, broken and burned.

By the time Ariel’s remains were returned to her family, Jacqueline, her mother, was already dead.

As Valya recounts, Jacqueline was deeply affected by her daughter’s brutal death. She had suffered from an illness which had dramatically worsened as a result of her daughter’s tragic fate.

To date, the remaining family have received no legitimate information as to what happened to Ariel. The closest they have to any explanation, with no certainty as to their veracity, are the stories spiraling throughout the reservation’s community. “Rumors are that she was thrown off [the bridge],” Valya said to Al Jazeera, visibly struggling to keep her emotions in check, “And that the people responsible went back down there and cut her in half… They burned her lower part of the body, and they left the upper torso.”

As for those conducting the official investigation, Valya’s questions were met with a firm suggestion from officers that Ariel had, in fact, taken her own life. Valya’s response was shock. “That’s not possible,” she asserts with fierce certainty, “My sister had no reason to kill herself. She was excited for my pregnancy and to meet the baby… She had a lot of stuff to live for.”

Speaking of her sister’s life, and the light she brought to all those around her, Valya recalls that, “She loved taking selfies with my grandpa. She’s the only one who can get him to take a selfie,” finishing with the assertion that her beloved sister “was a beautiful person, and she cared, and loved everyone… She wanted the best for everybody.”

As for any explanations from the federal government, there is only a keenly evident absence. “The FBI victim advocate, she just tells me that there isn’t much evidence to go to her case,” explains Valya.

Sadly, this is a typical response from the administration—in these cases, according to Al-Jazeera, “A lack of evidence is the main reason federal officials give for declining to prosecute crimes on reservations.”

Ariel’s case is just one example of the many indigenous women who have been lost to an epidemic of violence and brutality ravaging both the United States and Canada. Widely known by indigenous activists and communities as Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW), or Stolen Sisters, the plague of violence continues to not only needlessly rob families of their loved ones—valued members of cultures who have suffered, and continue to suffer, under colonization and oppression, in its myriad, horrific forms—but also these women and girls’ fultures, their potential, their precious lives, cut cruelly short.

The history of indigenous peoples under the domination of the United States and Canada is one as unspeakably monstrous as it is largely unspoken. The mainstream narratives of both countries ignores several critical facts: namely, that both of these settler colonial states are built upon stolen land, resulting in generations of immeasurable suffering, broken treaties, cultural destruction, enslavement, and genocide.

Settler colonialism is generally defined as “a form of colonialism that seeks to replace the original population of the colonized territory with a new society of settlers. As with all forms of colonialism, it is based on exogenous domination, typically organized or supported by an imperial authority. Settler colonialism is enacted by a variety of means ranging from violent depopulation of the previous inhabitants to more subtle, legal means such as assimilation or recognition of indigenous identity within a colonial framework.” These aforementioned North American nations are two of the most significant examples of this form of imperialism, which continues to enact itself in manners both insidious and conspicuous.

The colonization of the Americas began with wars of conquest and systematic exploitation of not only natural resources, but the native peoples of the so-called “New World.” They were the first populations to be enslaved by the colonizing European nations, dehumanized and considered chattel, creating the model for the Atlantic Slave Trade which would continue to classify similarly dehumanized African peoples solely as property for centuries. The Great Dying, one of the most monumental genocides in human history, is widely erased in Western historical narratives; this genocide, caused by a combination of merciless warfare, famine, slavery, and newly—sometimes intentionally—introduced European diseases, extinguished around 90% of the indigenous population of the Americas.

From the Great Dying to American ‘Manifest Destiny,’ from the subsequent ‘Indian Wars’ to Canada’s Indian residential school system, and other atrocities ranging from forced sterilization to assimilation, the two Western colonial nations are founded upon legacies of cultural, natural, and human destruction. These are the roots from which forms of discrimination and violence against indigenous peoples continue to emerge—including the disturbing issue of MMIW.

Due, in large part, to a lack of focus on this issue by the United States and Canadian governments, indigenous scholars and activists have shouldered the task of defining, analyzing, spreading awareness, and fighting against this epidemic. According to their painstaking and dedicated work, the problem of MMIW is one with three main pillars; these individuals’ disappear first, in their lives and deaths, second, in data collection and recording, and third, in the media.

The lack of visibility and protection of native women begins with the pervasive settler colonial attitudes which dominate societal narratives of both countries; including the complicated interactions between tribal and federal law enforcement, due to the supremacy of the countries’ government powers over tribal nations; and harmful stereotypes presented in mainstream media, on the rare occasions when these cases are covered.

Much of the data available on the MMIW crisis in the United States was compiled by Anitta Lucchesi—Doctoral Intern at the Urban Indian Health Institute (UIHI) and Southern Cheyenne descendant—and Abigail Echo-Hawk—Director of the UIHI and enrolled member of the Pawnee Nation of Oklahoma—in their 2018 report, “Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women & Girls: A snapshot of data from 71 urban cities in U.S.,” and in the database created in conjunction. Says Lucchesi, “For too long, data has been about other people telling native people who we are… It’s time that we tell the world who we are, and the world [to] actually listen to us.”

Due to the profound lack of thorough pre-existing material, the women took on the formidable task of creating their own corpus of information—combing through and assembling the sparse and unorganized available data, and using cartography to visibly represent the correspondence of the statistics to a greater history of dispossession and brutality. The database, as of November 2018, has over 3,000 logged cases, but the vast majority of them only come from the previous six years. Due to the prevalence of underreporting, particularly when attempting to trace the issue back to the beginning of the 20th century, Lucchesi estimates the actual numbers are drastically higher—closer to around 25,000 over the past century, in the U.S. alone.

The 2018 report begins with a disturbing disclaimer: “Due to UIHI’s limited resources and the poor data collection by numerous cities, the 506 cases identified in this report are likely an undercount of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls in urban areas.” The report demonstrates that, according to the CDC, murder is the third-leading cause of death for American Indian and Alaskan Native Women, with rates of violence on reservations showing a rate up to ten times higher. It also highlights the critical absence of examination of violence against indigenous women living in urban areas, made even more alarming by the fact that approximately 71% of indigenous people in the United States and Canada currently live off of tribal lands, in urban centers; with the U.S. census showing that over 50% of these individuals identify as female, queer, non-binary, or Two-Spirit. Further demonstrating the nature of this crisis, the National Crime Information Center details 5712 American Indian and Alaskan Native women and girls reported missing in 2016 alone, with only 116 of these cases logged with the Department of Justice.

In the arduous and crucial work of creating this report, several specific obstacles have impeded the efforts of the UIHI.

First, the UIHI faced problems with data collection, intrinsically linked to the systemic racism and sexism—ultimately rooted in settler colonialism—which causes the deaths themselves. These barriers included, but were not limited to, agencies refusing to release data, failing to search data, ignoring requests from the UIHI, or charging a service fee for access to what information they had.

The report also highlighted long-standing complications with law enforcement institutions themselves. Sarah Deer, a citizen of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, lawyer, and Professor at the University of Kansas, explains the historical origins of these adverse regulations, “In the late 19th century, the federal government imposed itself on tribal nations, and said, basically, ‘we don’t trust you to police yourselves’, and passed laws that allowed them to come into Indian Country and do crime control… It wasn’t a request of the tribal nations. And yet that’s still the law today.”

As previously mentioned, tribal police departments are stretched to the breaking point, without the funds, resources, or staff to address the issues that plague their communities. But these are far from the only obstructions—as a result of these federal ordinances, tribal law enforcement has highly limited sentencing power, even over their own citizens. By design, violent crimes occurring on reservations, such as homicide, assault, and kidnapping, can only be thoroughly addressed by the federal government.

Officer Willis Martine, a police officer of the Diné (Navajo) Nation, explains “The way the system is set up… if federal doesn’t take it, for whatever reasons, then you still can’t prosecute in tribal court for it; the maximum they could be given is a year in prison and up to $5000 fine… like for the homicide charge, on the tribal level. That’s the maximum right there.” Only because of tribal nations’ inability to adequately prosecute and sentence for serious offenses, he continues, “You would rather go with the federal level.”

Not only are tribal police forces barred from effectively preventing crime in their own communities, but they have no jurisdiction over non-native offenders—for any crimes, with the sole exception of a recent change which allows for prosecution of domestic abuse.

Roxanne White, activist and member of the Yakama, Nez Perce, Nooksack, and Grovont tribes, points out the discrepancies in federal and off-reservation law enforcement’s responses to crimes against natives, as opposed to crimes committed by natives. According to the Bureau of Justice, indigenous peoples are incarcerated at a rate 38% higher than the national average, demonstrating that while the protection of indigenous communities and individuals is continually all but disregarded, the same cannot be said of their prosecution.

In their study, the UIHI also found outside reports of 153 cases not documented by law enforcement, begging the question as to how many officially undocumented cases they could not find. As the UIHI points out, “No agency can adequately respond to violence it does not track.” It continues by connecting this lack of adequate action or concern on the part of non-native law enforcement to the ingrained roots of settler colonialism, tenably asserting that “continued research on racial and gender bias in police forces regarding how MMIWG cases are handled needs to occur.” Perhaps most sobering of all is UIHI’s discovery that nearly a third of perpetrators in MMIW cases are, for whatever reason, never held accountable by law enforcement. Valya Cisco, sister of Ariel Begay, gives voice to this disgraceful lack of either justice or peace for women like her sister, and those that love them, “I want justice for my sister, but it just seems like this person is still out there, around other daughters, sisters, aunts, grandmas—he could do it again, like he thinks that no one can convict him of the crime.”

Activists march for missing and murdered Indigenous women at the Women’s March California 2019 on January 19, 2019 in Los Angeles, California. Photo by Sarah Morris.

Perhaps the most visible factor of all is the problematic narratives propagated by the media, blatantly evident in the rare presentations of this epidemic. According to the UIHI report, over 95% of the cases they documented were not covered in national or international media. Another troubling component was the media’s disproportionate focus on the violence taking place on reservations; which, UIHI notes, “perpetuates perceptions of tribal lands as violence-ridden environments, and, ultimately, is representative of an institutional bias of media coverage on this issue.”

The media also approaches these cases by proliferating what the UIHI terms ‘violent language,’ which includes but is not limited to racial stereotyping, misgendering trans victims, and victim blaming. In their analysis of available articles, the UIHI found that nearly a third of all media outlets examined included such violent language in their reporting; and horrifically, 22 out of 46 of these outlets used violent language in 100% of their coverage of MMIW cases. Instead of the media coverage centering the voices of the indigenous populations affected to productively raise awareness, respectfully honor these losses, and galvanize allies into action, the vast majority of their reporting causes still more harm.

Numerous other hindrances faced the UIHI in their creation of this report. Speaking on the report she co-authored, Abigail Echo-Hawk cautions that “What we know is this is barely scratching the surface.”

When asked to explain the specific reason for the MMIW crisis, Anitta Lucchesi states, “The reality is, unfortunately, there is no one reason,” and elaborates, “The one unifying factor would be colonialism and ongoing colonial occupation. It teaches people, whether native or non-native, to undervalue native women, to see us as less than human, to see us as exotic and sexy, and easy to use and abuse.”

The UIHI’s essential report ends with the resounding closing statement: “The lack of good data and the resulting lack of understanding about the violence perpetrated against urban American Indian and Alaska Native women and girls is appalling and adds to the historical and ongoing trauma American Indian and Alaska Native people have experienced for generations. But the resilience of American Indian and Alaska Native women and girls has sustained our communities for generation after generation. As the life bearers of our communities, they have been integral to holding strong our culture and traditional practices. Bringing to light the stories of these women through data is an integral part of moving toward meaningful change that ends this epidemic of violence. UIHI is taking huge steps to decolonize data by reclaiming the Indigenous values of data collection, analysis, and research, for Indigenous people, by Indigenous people. Our lives depend on it.”

The high cost of reducing human beings, in all their complexity and innate value, to mere stereotypes, even objects, has been illustrated in countless horrors over the centuries, and to this day continues to devastate peoples marginalized by the dominant systems of power and those who, to varying degrees, participate in them. These statistics are appalling in their own right, but even more so when comprehending each number as an individual, inherently precious in all their flawed and magnificent singularity.

“As Native women, we give life to our people.We pass on the knowledge of our culture to the next generation. Our hearts beat with the blood of a thousand past and future generations… For every Native woman that goes missing or is murdered, our people lose our future. Future mothers and grandmothers, future artists, future teachers, future lawyers, future leaders,” states Native Hope in their video on MMIW, continuing to say that thorough education and increased awareness are the first steps toward preventing, resisting, and battling this deep-rooted, settler-colonialist crisis.

The little to no support received from law enforcement, the justice system, or any major government power results in the families and communities of the disappeared women undertaking the searching themselves. They often receive no closure, justice, or answers as to why their loved ones were taken from them; but they continue to fight the crisis. UIHI Director Abigail Echo-Hawk elucidates this resistance, “If you look in a history book, you’re going to see language that talks about us in the past, living in teepees or igloos, but nothing about the current incredible, strong, resilient people that we are today… Our resiliency has always been action, and in that action, we are not only sustaining our own communities, but we are part of building a better America.”

One thing which helps the surviving loved ones of lost MMIW individuals, is to remember them, to honor them, to tell their stories, to ensure who they were and what happened to them will not be disregarded, forgotten, or trivialized. It is of the utmost importance that allies do this as well, celebrating these individuals and their lives. Most importantly, we must take action to protect indigenous femmes and communities as a whole, to use our privilege and position to elevate their voices and sovereignty, and follow their examples to prevent this epidemic from continuing to claim precious lives.

Many falsely believe death to be the great equalizer, but it is also evidence of the many violent expressions of inequality. The oppression of indigenous cultures and marginalized bodies in life is mirrored by the brutalities and violations enacted upon them in death. Knowledge of these facts do not exist in a vacuum as merely a tragedy to be mourned. Instead, they must provide a foundation to motivate and catalyze action within larger movements seeking to ensure indigenous sovereignty and the rights of indigenous women, girls, two-spirits, NBs, queer folk, and peoples as a whole—their rights to a good life, according to their own specific cultural and spiritual principles and worldviews, and equally importantly, a good death.

Anna V. Bayona-Strauss studies Comparative Literature at Fordham University, and alongside literature, is very passionate about history, cultural studies, human rights issues, environmental issues, film/television, folklore, cosmologies, theology, and, naturally, death. She/they writes non-fiction and fiction, performs as an actor and singer, and can be found on Instagram @citizencinematrix, and Twitter @citzncinematrix.

SOURCES

Urban Indian Health Institute Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls Report

Al Jazeera’s The Search: Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women | Fault Lines

Huffington Post’s Why Are Missing And Murdered Indigenous Women Cases Being Ignored? | Between The Lines

National Congress of American Indians Violence Against American Indian and Alaska Native Women Report

The Outline’s Ariel, 26, Missing

ACTIONABLE RESOURCES

Lakota People’s Law Project MMIW Resource Guide

National Indigenous Women’s Resource Center

Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women USA

Coalition to Stop Violence Against Native Women

Native Women’s Society of the Great Plains

November 18, 2020

Nana’s Wig

It’s Saturday morning in the summertime, and you are seven. Your grandmother takes you to Fulton Street in Brooklyn. She’s shopping for a wig, and she’d like you to hurry up. Saturday is the worst day to buy wigs. You and your sister follow her as she surveys the wigs in the shop. As in all things, but especially wig shopping, your Nana takes her time. After a million light years, or perhaps 20 minutes, your grandmother chooses a chocolate brown wig and motions to the shopkeeper. “Aren’t you going to try it on?,” you ask, but she shakes her head. “I know this head better than anyone. I know what looks good on it.”

Later that night, at dinner, your grandmother debuts her new wig. She’s right, of course. She looks beautiful.

***

It’s another Saturday morning in the summertime, and you are ten. You are sitting on the sofa, turning the pages in your grandmother’s photo album while she says good morning to her fish by tapping the aquarium glass with her manicured fingernails. You point to a picture of a nondescript building and ask about it. Your grandmother peers over your shoulder and says, “That’s the funeral parlor.” They called them parlors back when she was a little girl. “The last good one. It’s closed now.” You ask her what made it good. She takes a pull on her cigarette before she answers. “They knew how to make us look good.” Your grandmother doesn’t say who ‘us’ is, but you know it’s Us. It’s Black folk.

***

It is summertime two years later, and she is watching you comb your hair. You are rushing, but there are more knots than usual. The knots crackle as your comb moves through them. You are fixing your hair before you, your sister, your mother, and your grandmother go to the mall. The shopping center is only three blocks from your house, but you have to look presentable before you leave your apartment. There’s a new wig on your grandmother’s head, this one with an auburn tint. Nana scratches her hairline under the wig, careful not to disturb her appearance. She’s always been a beauty, that one.

You place the bulk of your hair year in your right fist and use your other hand to position an elastic until your ponytail is sufficiently puffy. Your grandmother stops you.

“How long has it been since you’ve had your hair done?”

“A while,” you say, and it’s the truth. You’re saving money to go to the hairdresser, but you don’t have enough just yet.

Your grandmother shuffles over to get her handbag from the kitchen. She unclasps the bag and pulls out two $20 bills.

“Here,” she says. “Get your hair done.”

“You didn’t have to do that,” you say, and you mean that, too. “I’ll have enough money in a few weeks.”

She waves your protest away as she shuffles back to her chair.

“Remember, half of that hair on your head is mine now, so take good care of it.”

You fold the money into your back pocket and go to the mall with your family. You don’t remember what you bought, or how long you stayed there. That part of the recollection slid into the sea of the forgotten a long time ago.

Years pass. Decades.

You go to funerals. Not many, but enough to see what your grandmother meant about the ‘good ones’. Beautiful brown skin turned gray by the wrong makeup. Lipstick that no Black woman would ever wear. And the worst, wigs that lay askew. Tugged on as an afterthought, like a child who has been told by a parent to put on a scarf before he goes outside to play. That is to say, with a tinge of resentment and a handful of carelessness.

***

Your grandmother wears wigs; a new one every time you visit her. Some days it’s an afro, other days its tight ringlets. Nana likes to change things up.

One time, you get your hair straightened, and you show your grandmother. “It ain’t got no curl,” she sniffs. “You’ve gotta have some curl, even if it’s just a little.”

You’re a teenager now, so you don’t want to take her advice, but when she walks away, you grab a curling iron and make a few curls.

At dinner, she smiles at you and points at her wig. “I know what I’m talking about.”

You smile back, because you know she’s right.

1960s vintage advertisement for Star Glow wigs.

Your grandmother is sick. She has circulation problems in her legs, and her doctor recommends surgery. It is December of 2007 when she agrees to the surgery. Your aunt, your sister and you drive from Georgia to Indiana to be with your mother and grandmother for the surgery. The nurse wheels her away for the operation and you sit in the waiting room eating M&M’s and giggling with your sister. Things are good, but they go bad quickly. In the hospital, the nurse pulls your family to the side and tells you to wait for the surgeon in a small room. The doctor tells you there have been complications, but your grandmother is resting in an ICU. She’s intubated, but awake. You gather your things and go visit her, and a single tear slides out of her left eye and slides down her cheek. You kiss her, fix her wig, and walk away, the bag of M&M’s balled up in your right fist. You decide you hate M&Ms while you stand in the hallway and cry.

You don’t think things can get worse, but they do. The nurse mentions your grandmother’s breast cancer as if it’s a known fact. It’s not. Sleep happens on the floor in hospital conference rooms and on empty gurneys in hallways. The doctor comes in and briefs you often. His cellphone rings as he talks to you. He turns it off without looking to see who’s calling. You appreciate that. His ringtone is the Batman theme. You decide you now hate Batman as well.

You are a zombie, but you don’t know it. You don’t know what to do, so you fix her wig whenever you can.

You go back to Georgia, but then come right back. At some point, the United States swears in its first Black president. Your grandmother, scheduled for another surgery, misses the moment. You go back to Georgia again. Then come right back again. This time, for the final time.

She’s not well, your grandmother. You know this, but you don’t want to accept this. You think about how proud she is, how she never has a hair out of place. She’d hate for anyone to see her without her carefully drawn eyebrows and red lipstick, wearing a scratchy hospital gown. Your grandmother loves to pose for pictures; she was married to a photographer. Because of this, it was always important to her to be camera ready. You do your best to make her pretty.

Your mother has moved your Nana from the hospital to a private room in hospice. You and your aunt sleep on the floor in her room that first night, waking up every few minutes to check on her. In the night, your grandmother tries to lick her lips, and you run out of the room to find a nurse. Water, you need water. While you hold the straw to Nana’s lips, you fix her wig. Her eyes stay closed as she drinks. She takes two impossibly tiny sips, then no more. You want her to drink the whole glass, in big gulps. You imagine going to the nurse and saying something like “my grandmother sure is thirsty today.” You want this more than anything.

Instead, a nurse with the kindest voice you’ve ever heard, gives you a pamphlet about the end of life. You devour the entire document, reading passages over and over. You convince yourself she’ll recover. The nurse’s shift ends and you say you’ll see her the next time she works, which will be in two days. She pauses and looks at you like she’s trying to gauge your frailty. You don’t look her in the eye, so she says goodbye and gives you a hug before she walks out the door. You call your husband from outside the chapel at the hospice and ask him if your grandmother will pull through. He pauses for too long before saying “I don’t think so, honey,” and you know it’s the truth, but you hang up on him anyway.

That night, her last night, you and your family sit at her bedside, play Sam Cooke on compact discs, and eat strombolis. Her sister calls to say goodbye. And just like that, she stops breathing.

We call the nurse, and we sit and watch as her heart stops beating. and we sit in stunned silence.

A lifetime wasn’t enough.

You and your family bathe your late grandmother, readying her for the funeral home attendants. Someone must have told them. The nurse, of course. She must have made a discreet call while we tended to Nana. Two attendants (one early twenties, one middle-aged) come in to take your Nana away from you, and you want to run screaming down the hallway, but you won’t leave her. Not now.

The attendants pick your grandmother’s body up and her wig slips to the floor. You realize you’ve never seen your Nana without her wig. Her hair is thin, wispy, and white. This is wrong. All of it’s wrong. One of the attendants, the young one gasps and turns to his partner. “I’m not touching that,” he hisses to his coworker. You want to scream, but you don’t. Your sister, always the strongest one, reaches down and grabs Nana’s wig. The two of you position it on her head and glare at the younger attendant, who has the good manners to look embarrassed by his outburst.

They take your grandmother away in a hearse, and you follow behind in your car for a while. Eventually, the hearse goes straight, and you turn, and it’s like someone tore your spirit away from you.

***

Nana is gone and for a long time, it hurts to think about her. Everything that happens in the world now, happens without her. For a long time, it’s unbearable. One day, you start looking through family pictures, and you start counting Nana’s wigs. You make it up to 12 before you stop. You miss her, and you always will.

You isn’t you. It’s me.

I still don’t like Batman. I prefer other candies besides M&M’s. I’ve often wondered about the funeral home attendant who didn’t recognize my grandmother’s crown when he saw it. All he saw was hair. But I saw more than that. I saw her. For just a moment, if only for her sake, I wanted him to see her too. I wish, when my mother was making funeral arrangements as my grandmother lay in the hospital, someone at the funeral home would have taken a moment to ask about Nana’s pride, about her signature. About how Nana wanted the world to view her. Because my Nana? She knew a thing or two about looking good.

Erica Gerald Mason is an Atlanta-based freelance writer and journalist. Erica’s articles have appeared in People, The Wall Street Journal, Serious Eats, Byrdie, Vanity Fair and more. Connect with Erica on Twitter at @ericapretzel or on Instagram at @erica.pretzel.

November 11, 2020

Whose Green Burial is it Anyway?

In 1889, over 100 years before the first conservation cemetery was founded in the United States, a man who was just beginning his journey to become “The Father of Environmentalism” sat deflated in a high mountain pasture in the Sierra Nevada Mountain Range. John Muir had emerged from his campsite, furious to see the devastation that a flock of sheep had wrought on the grassland of this “cathedral” of mountains. He drew a line on a map through the Sierra Nevada Mountain Range to outline the piece of wilderness he hoped to call Yosemite National Park. Muir seemed not to notice, Yosemite already had a name: “Awahnee” meaning “gaping mouth-like place” named by the Awahneechee people who lived in the grand valley of the mountains. Years earlier, in the 1850’s, the Awahneechee people were massacred when a group of white men set fire to their wigwams. What Muir defined as a place of true “wilderness” where “no mark of man is visible” had already been a space of community, harmonious with the Land. That is, until the Land was forcibly taken from them.

Ahwahneechee land, photographed by Koren Stevens

This is only one example of how environmentalism has the propensity to overlook and exclude the histories and cultures of marginalized populations who do not fit neatly into their narrative. In the 21st century, we are only just beginning to unpack these harmful ideas, formed in the name of good will and science. Part of this unpacking process compels us to discuss the Green Burial movement. The movement emerged in the early 1990s, as part of a larger countermovement addressing the dissatisfaction some felt with the American way of death (known for being manipulative, corporatized, stuffy, and needlessly expensive). Green Burial, takes a few different forms, but mainly is understood to be the burial of a body that is not chemically embalmed and is placed directly into the Earth in a compostable coffin or shroud. The movement takes a political tone when it lobbies the government for changes in regulations for funeral homes and cemeteries, and much of its focus is on issues of climate change and sustainability. It is therefore viewed as a part of the larger environmental movement that has been active in the United States since the 1960s.

I report on this movement as a white woman who has traveled in select Green Burial business/activism circles for a few years now, and these circles are majority white. I am not the first person nor the last to point out this uncomfortable fact. There is no doubt this can lead our advocacy to be oblivious to the issues our BIPOC counterparts experience daily. For example, we don’t often talk about why it might be hurtful to a Black family to denounce embalming and post-mortem restoration/reconstruction. We don’t often consider that it might be triggering to a Jewish or Armenian family when we suggest an unmarked grave in the woods. The Green Burial Movement has largely overlooked Indigenous people who have long been practicing burial in a sustainable way, and that their traditions are deeply rooted in the relationality of their cultures, which have since been erased in the name of science and environmentalism. I’m not suggesting the Green Burial movement is openly hostile to these groups, but I am saying we can often miss the mark in understanding the deep and emotional legacies that are present in views of the body and burial.

The term I find most apt here was coined by Anthropologist Franz Boas. “Ethnocentrism” which is defined in the Oxford dictionary as the “evaluation of other cultures according to preconceptions originating in the standards and customs of one’s own culture.” Michelle Acciavatti, who is a Funeral Director at Ending Well and President of Vermont Natural Burial spoke with me about having to reassess her experiences in the Green Burial world through the lens of ethnocentrism.

“I’ve been training for 7 years and there’s just a lot about what I was taught that totally erases a huge portion of the people involved in the Green Burial world. My training has all been done by primarily white women of a certain age. There’s been very little cultural diversity. […] I’m realizing that I have to unlearn so much of the foundational stuff that I was taught because it erases and leaves out so much history.”

Sometimes this erasure can be purposeful, like in the case of Yosemite National Park and the Awahneechee, but much of the time it is merely a byproduct of a primarily white and Western world view that has codified it’s experiences as universal. Acciavatti again:

“When describing natural burial we often revert to using language like ‘it’s burial just like it was before the Civil War’ as if that’s a really great and wonderful time to go back to. […]We don’t examine that we talk about home funerals as if we’re returning to this type of deathcare, but there are cultures that have never actually lost home deathcare. A lot of traditional religions (whether it’s Islam or Judaism, and even aspects of Christianity) they still very much take care of the body themselves. Additionally, there are a lot of people that come as immigrants or migrant workers and keeping the body at home and not working with a funeral director is part of their culture. These are just a few examples of groups of people who do not have to reintroduce natural burial to their communities, so when we frame the issue as a reintroduction it’s clear that we’re talking about and talking to a white community, but we never call that out as something that is specific to the white community.”

Race and Embalming/Post-Mortem Reconstruction

In her article “Race & The Funeral Profession; What Jessica Mitford Missed” Dr. Kami Fletcher illuminates how ubiquitous it is for white death industry professionals or experts to gloss over the vastly different experiences of communities of varying ethnicities. Jessica Mitford’s book, The American Way of Death published in 1963, has informed and directed the battle-cry of Green Burial activists in a way that perhaps no other book has. And yet, Jessica Mitford’s book exposed the corruption of the funeral industry as if it were a universal monolith.

“Just who were these American funeral directors that Mitford tried and found guilty in a public court of opinion? From 1900-1960’s, the initial study period of her book, who were viewed as American funeral directors? It definitely was not the African American funeral director because she/he was living under Jim Crow segregation – barred based on race from even obtaining membership in the National Funeral Directors Association. […] African American funeral directors led the charge in the Civil Rights Movement by using their funeral parlors as meeting places. They threatened not to buy their funeral cars from white establishments if they didn’t hire African American workers. African American funeral directors bailed-out jailed protesters. […] [They] fought for justice; they did not have time to collectively concoct schemes to exploit the bereaved” (Fletcher, “Race and the Funeral Profession”).

This is not to say that the premise of Mitford’s book is incorrect, but rather to demonstrate how white activists may unconsciously consume information that leaves out large parts of the narrative of marginalized people. As presented in The American Way of Death, funeral industry methods like embalming are presented as a moral depravity to be fought against. Activists often fall into the trap of broader character judgements like, “embalming is morally wrong.” But what about the times when embalming is actually resistance and social justice?

“The job of the African American undertaker was to take care of the body with dignity and respect. He/She had to make the police officer’s bullet holes disappear, hide the rope marks from the lynching, the infinite bruises from the KKK terrorists. An open casket funeral is a staple in the African American funeral tradition; funeral goers expect for their loved ones to look just like themselves” (Fletcher, “Race and the Funeral Profession”).

When ethnic violence and genocide is not a collectively shared part of one’s history it is easier to overlook the importance of postmortem restorative procedures in the death customs of cultures who do have that tragic shared history. Sarah Wambold of the Campo de Estrellas Conservation Cemetery in East Texas spoke about this in more detail.

“Those of us who work in this type of deathcare must do more to consider the ways in which natural burial repackages what for some groups has been about dispossession of land and of legacy. This revision is its own type of appropriation. We must acknowledge the revision and privilege of calling what is essentially an unmarked grave ‘natural burial’ because we know our legacy is intact.”

Photo by Tom Bailey

Unmarked Graves and Genocide Survivors

The issue of legacy and memorialization is another hurdle that most Green Burial cemeteries need to overcome. Much of the anxiety surrounding death has to do with legacy and being remembered. To Green Burial activists, gravestone memorialization often goes against the whole premise of Green Burial– leaving no trace upon the Earth. But just repeating that line does nothing to reckon with the anxieties held by those who carry the burden of a cultural history where they were denied material expressions of legacy like gravestones.

When the Eastern European Jews returned to their homes after the Holocaust they now had to deal with the aftermath of unmarked mass graves, where Jewish people were discarded with no respect to their traditional burial customs. Researcher, Sarah Garibova writes,

“Throughout the postwar decades, survivors strove to bring their relatives “to a Jewish grave”—in other words, to provide them a burial consistent with Jewish burial norms.[…] Although grave exhumation is generally prohibited in Jewish tradition, Soviet Jews did not embrace exhumation out of religious ignorance, but instead performed them out of a desire to approximate traditional Jewish burial norms under novel, catastrophic circumstances. The site was located on land that the Soviet state recognized as Jewish burial ground and the victims were already interred alongside the graves of their ancestors—conditions that fulfilled two of the major imperatives of traditional Jewish burial culture. All that remained was for survivors to cover over the exposed bones and erect a grave marker—steps intended to protect the remains from view and safeguard them against future disturbance” (Garibova, “To Protect and Preserve”).

Although there is no Jewish law requiring the marking of the grave, “matzevot” (markers of wood or stone) have been a “part of European Jewish Cemetery tradition for more than a thousand years”. This history is made even more complicated and sensitive by the Holocaust, which resulted in the unmarked mass graves of millions of people. When conservation cemetery sales people from a Christian or nonreligious background speak to Jewish families who are uneasy about the lack of a grave marker, they must acknowledge this trauma, instead of dismissing it as “not understanding the point” of conservation burial.

Image via Everplans

The Othering Language of Science

In 1970 at the first Earth Day celebration, a group of Indigenous people attempted to disrupt the proceedings, claiming that white activists had sidestepped the Chippewa tribe in policy-making decisions that directly concerned them. Senator Gaylord Nelson, one of the sponsors and organizers of the event, had spent 10 years attempting to absorb Red Cliff and Bad River reservations into the Apostle Island National Lakeshore in Wisconsin. According to Professor Dorceta Taylor’s report on Diversity in Environmental Organizations,

“Some White environmentalists perceived Native American attempts to link social justice with environmental affairs to prevent the conversion of parts of their reservation into public parks as anti-environmental. Park advocates did not understand the significance of tribal sovereignty or the reasons why tribes insisted on control of their homelands” (Taylor, “Diversity in Environmental Organizations”).

To the white environmentalists of the 1960s and onwards, caring for the Earth did not offer any grey area. The goal was to establish more protected lands, it did not matter if that land was occupied by Indigenous people who had been and would continue to live in a sustainable way. In their minds, restricting the land was protecting the land. Groups seeking to insert social justice into the mix of environmentalism were largely ignored or purposefully pushed out. As we see even now, racist views were obfuscated behind numbers and statistics and pitched to white environmentalists as irrefutable science.

Just like in the early environmental movement, there exists a subtle, yet purposeful inclination to justify the need for Green Burial in the language of science, a supposedly impartial judge of right and wrong. Calculations of figures like carbon footprints, chemical half-lifes, and decomposition timelines have led us down the exhilarating road of divine right through scientific discovery, but what we fail to rectify when we sell our plots is the deeply personal, existential, and relational choices of those who have already discovered this path. In an interview with the Ernest Becker Foundation, Sheldon Spotted Elk, speaks of the tendency to use the language of science to erase,

“In Western society, […] the whole idea of science is for us to come to the “one truth.” Whereas in Cheyenne philosophy, it’s ok to have two different perspectives on the truth, and both can be right. To be clear, I’m not anti-science, I’m pro-science, but I think this influences Western society to really create a mentality of “I’m right, you’re wrong, I’m sophisticated you’re unsophisticated, I’m civilized you’re uncivilized”—these clear markers that make it easier to discriminate.”

Sky above Ahwahneechee land, photographed by Koren Stevens

In the movement’s attempt to sell this type of burial to a broader public, we have relied heavily on the argument that anything other than Green Burial is a moral compromise at the expense of the environment. In doing so, we have largely failed to meet people where they are, and reconciled with sympathy and open-mindedness that cultural traditions are not created in a vacuum.

When the battle-cry of the movement is “embalming is toxic,” even with the scientific truth behind this statement, does this really create a comfortable environment for a Black mother looking to hold a funeral for her son after a police officer stood on his neck for nine minutes? When monumentation and headstones are so quickly dismissed as antithetical to Green Burial activism, would this not confuse and trouble a Jewish family, who have been practicing Green Burial for generations and desire a physical monument to their legacy? When an Indigenous person gets a newsletter in their inbox about the “revolution” in death-care, does that leave a bitter taste in their mouth? The answers to these questions are not always uniform, because people organized through identity are individuals, and not a monolith. For us as white people involved in Green Burial activism, it is not our duty to answer these questions –only to consider them, listen with an open mind, and use history as our guiding light in informing the context of the words we choose to use.

When I die, I want a Green Burial. Green burial and other sustainable initiatives are also the direction I hope the world moves toward to combat climate change. When climate change ravages communities it won’t be the wealthy and white communities who suffer. Black and brown people will disproportionately feel the consequences of our inaction, yet how we talk about the issues of environmentalism centers a white audience. We need to be more inclusive in the way we talk about Green Burial, because social justice has always demanded that from environmentalism, but so rarely have white environmentalists ever risen to the occasion.

Corinne Elicone is the Events & Outreach Coordinator at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts. She curates Mount Auburn’s death positive programming, online video content, and historic walking tours of the grounds. She has written for NursingClio.org and currently writes and researches a blog series on New England burial grounds called Beyond the Gates. She is a Green Burial advocate and is also Mount Auburn’s first female crematory operator in their near 190 year history. Twitter: @CorinneElicone Instagram: @SoundAffects

The Collective for Radical Death Studies is a nonprofit organization whose members view death work as synonymous with anti-racism work. The Collective actively works toward dismantling oppression, centering the experiences of marginalized peoples, and decolonizing death in study, practice, and experience.

Caitlin Doughty's Blog

- Caitlin Doughty's profile

- 8406 followers