Caitlin Doughty's Blog, page 40

February 5, 2015

Washing Kathryn, Touching Death

Preparation Room Table

She is lying, partially wrapped in a plastic sheet, on a cold metal table in our prep room. Her head is tilted slightly away from me so I can’t see her face yet. I can see she is still in her hospital gown and there is a port still attached to her neck. I take a deep breath and walk toward her. As I come around her head, the row of staples on her scalp goes from her hairline back behind her head where I can’t even see them end. There is another row above her ear and her skull is obviously missing from under her skin between the two tracks. Her curly hair is matted on one side, shaved on the other. I have a full view of her face now.

It is definitely her, but not her. Kathryn, my friend, is lying dead in front of me. We worked together before I became a funeral director. We worked in an intimate environment where co-workers become family. I hadn’t seen her in few years. She traveled for work a lot, I started a different career. But she was my friend. Here she was in front of me, and I had a job to do.

Her wife was meeting me here to prepare her for burial. Lisa had called me when Kathryn died on the East coast, asking me to help bring her home. Kathryn had been through so much in the last few weeks of her life. A sudden medical crisis that was never fully diagnosed culminated in a stroke after many other unexpected complications. Interventions and multiple surgeries had been fruitless. Because she was so young the doctors just kept trying everything to fix her. A week before, Lisa made the incredibly difficult decision to move her to hospice care so that her poor body could finally rest.

Lisa and I had had a long conversation on the phone about embalming. It is not a required procedure in our state or the state that Kathryn died in, but many people just believe it is necessary or even mandatory. Lisa had done her research, and I helped her with the facts and weighing the pros and cons of the procedure, but she made the decision. Kathryn had been through enough, she did not need another invasive procedure on top of all that. She could be shipped home on ice, in a Ziegler Case.

Ziegler Cases

Kathryn was going to be buried in her family’s plot outside town. Since many members of her family had not had a chance to see her before she died, we were going to have the time before the funeral service to let those who wanted to view her have their time to do so. Lisa decided she wanted to prepare Kathryn herself and asked me for my help.

So there I was, standing next to Kathryn’s body, waiting for Lisa. I had arrived early knowing that I would need this time alone with her body. I needed this time for me, so that I could be there for Lisa.

Not always necessary.

You set up barriers when you work with the dead, both physical and emotional. I have seen literally hundreds of dead bodies in the last few years. When I started in this business, I did removals; picking up bodies from their place of death, and transporting them to our care facility. Physically you are wearing gloves, even gowns when the occasion calls for it. You are not actually coming into contact with the dead person. You don’t know this person. It’s just another body, special to someone else so you treat it with respect, but you have no attachment to it. I would help families dress the body in the home before taking it away if they wanted. Once I helped wash and brush out a woman’s hair while she was still in her bed so that her daughter could make a braid to cut to keep. It’s like manipulating a life size Barbie.

After a few years, I was spending all of my time just in our offices making arrangements with families, rarely seeing the bodies unless there was a service. At that point someone else had prepared the body for viewing, I might help rearrange the hands, or touch up the hair or makeup, but I had very little actual interaction with the deceased.

Barriers have a way of crashing down when it is someone you know, especially an unexpected death of your peer. I knew this wouldn’t just be another body. This was Kathryn. But it wasn’t her. I needed time to sit with her to digest that. I was there to support Lisa. I was the professional. I was the one experienced in death. I took a few minutes just to touch her face and hands, rationalizing the cold I felt with the woman I had known. I finished removing the plastic sheet she had been wrapped in, leaving her hospital gown on. I covered her in a cloth sheet up to her neck. I had offered to have her bathed before Lisa got there, but Lisa was emphatic that she wanted to be involved with everything.

Lisa arrived with three suitcases. She had been having trouble deciding what to dress her in, so she brought everything. I had told her to bring Kathryn’s toiletries. We could use her own shampoo, conditioner (key for us curly haired girls), and soaps. It would help her smell like her again, rather than smelling like hospital.

Outside the door to the prep room, Lisa started to cry. “I’m scared!” she said. I held her for a moment and then started to describe what she’d see when I opened the door. “She’s lying on a metal table, covered in a white sheet but you can see her face. There is a lot of weird looking equipment around because they use this room for embalming but we aren’t using any of that. Her head is really sunken in on the side where she had the craniectomy. Her skin is a bit mottled with patches of red. There are some grey sticky spots on her arms and legs, probably left over adhesive from the medical tape. We can see red veins in her arms and legs where blood has settled. It’s called ‘marbling.’ Her eyes and mouth are closed and are concave looking. It still looks like her, but it’s not her.” Lisa collected herself and I opened the door.

I gave Lisa the same kind of time I needed when I’d first come into the room. She cried, hugged her, touched her, talked to her for a bit.

She looked at me, “What do we do now?”

“Do you want to bathe her?”

“How do we do that?”

With a task at hand, we put on aprons. We removed the remaining tubes and IVs that were on her. I made the conscious choice to forgo the latex gloves for this washing. I wanted to be me, her friend doing this for her, not her funeral director. I turned the water on warm. Lisa laid out the things she had brought. I handed her a washcloth. We started at the shoulders, each of us on each side of her. We passed the soap back and forth as we worked our way down her body. We inched her gown and sheet down as we went, before giving up and removing it all together. Flecks of blood and the medical adhesive washed away. Lisa decided to clip her nails and shave her legs. I washed Kathryn’s hair with her own shampoo and conditioner. I used a comb to get the knots out of the hair that she still had. Once those curls were clean and flowing, she looked much more like herself.

Lisa and I talked some as we worked, told some stories but we were both very much in our own heads working through this. Only after the fact did I think we should have had music playing in the background.

Once Kathryn was clean and dried, Lisa went to choose the clothes. She had been debating whether to put her in a dress, or in street clothes. While Kathryn looked great in a dress, she really was a T-shirt and jeans kinda girl. In the end, Lisa picked out a well-worn pair of Levis, a fitted long-sleeve shirt, and a wool cap with Kathryn’s team’s logo on the front. Lisa and I worked together to get her dressed. We laughed a bit at how difficult it is to dress someone who is not cooperating. I compared it to dressing my tantrum-ing two-year-old, no wait, this was easier. When we were done, tears caught in my throat.

The change was so remarkable. I had come into the room with a body that had been through so much. She looked beat up, cold, lonely, and pained. Once she was dressed, in her own clothes, she looked so cozy, warm, relaxed, and comfortable. She looked like herself. But it wasn’t her.

Lisa laid her head on her wife’s chest and cried. She spoke to her, telling her how much she loved her and missed her. She kissed her. She touched her. She held her.

It was almost as hard to leave the room as it had been to come into it. I helped Lisa pack everything up and walked her out to her car. We hugged for a long time. We’d see each other the next day at the service. I noticed we both took a long time starting our cars and leaving.

It has taken me a few weeks to put this experience into words. The images and emotions are continuing to ricochet around in my head and writing about it helps make some order of the chaos of grief.

I wanted to share this experience so that people can take a look behind the curtain to see that being so closely and intimately involved with someone’s body after they’ve died is an amazing experience. Amazingly painful, amazingly sad, but amazingly rewarding.

Nora Menkin is the Managing Funeral Director at The Co-op Funeral Home of People’s Memorial. She has been a funeral director since 2007.

January 29, 2015

January 22, 2015

Ask a Mortician- Human Taxidermy?

January 15, 2015

Identifying Bodies at the Morgue is No CSI

Death in DC.

Once or twice a month, my alarm clock goes off at 7 am on the weekend, I pack a peanut butter and jelly sandwich and a thermos of coffee, and board the green line metro to the DC Consolidated Forensic Laboratory. I’m a grief counselor and I work part-time helping people identify their deceased loved ones at the DC Office of the Chief Medical Examiner.

Let me start out by saying that working at the medical examiner’s office does not at all resemble an episode of “CSI” or “Bones” lest imaginations start running wild. If reality was like CSI, I would have a much more expensive wardrobe and my lip gloss would always be perfectly applied. There’s no dramatic drawing back of a curtain or sheet to reveal the body in question while someone gasps “That’s him!” and faints to the ground. All identifications are done by a photograph and the person making the identification is usually 99% sure at that point that the decedent actually is their friend or relative.

The first step when working with an individual or family at the Medical Examiner’s office is to bring their anxiety level down as much as possible and bring support into the room. I introduce myself, explain who I am, and let them know I will be with them during the entire identification process. I express my genuine sympathies for their loss. I also let them know that the identification will be done by photo and that everything takes place in the room that we are currently sitting. Great detail about the process is given so that individuals know exactly what to expect. Fantasies are often worse than reality. After all, the person making the identification of the decedent has probably also watched crime dramas on television and could be envisioning the worst.

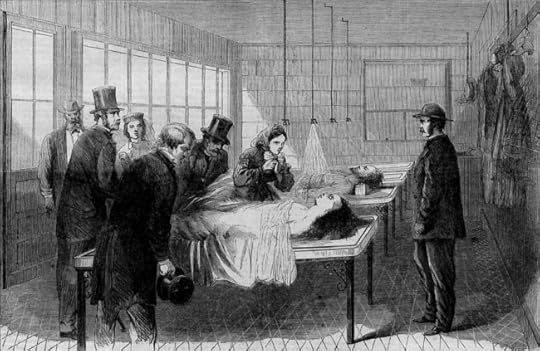

First morgue in New York City, 1866 at Bellevue Hospital.

I take immense care to explain how the photo is viewed and what the photo will look like. I explain that the photo will be presented face down on a clip board and will be a picture of their loved one’s face surrounded by a blue sheet similar to those found in doctors’ offices. I make them aware of any potential marks that may have resulted from an accident or medical intervention. I let them know they can take as long as they need to turn the photo over on the clipboard and view the image. No matter what is going on outside the identification room, I convey that I have all the time in the world for this family.

The goal of my job is to help make the process of identifying the deceased as gentle as possible. Humans generally have an instinct to help when they see someone else hurting. I am no exception. But for the individuals that come to make an identification at the Medical Examiner’s office, I have to accept that I can’t take away their pain in our one brief encounter.

What I can do in my role as a grief counselor is prevent people from becoming re-traumatized during the identification process. Often individuals I encounter at the morgue have experienced some type of trauma resulting from facing a sudden or unexpected death. Trauma is defined as an incident involving actual, or the threat of, death or serious injury and involves feelings of shock, horror, and fear. And for many making an identification of a loved one at the DC Medical Examiner’s Office, this experience is just one in a long line of traumas.

“Body of Proof.” Nope, not how it is.

Once the identification is made, I talk with the individuals about resources that might help them and connect them to various social service agencies if needed. I let people know about where they can get long-term support and mental health counseling. Sometimes people need help and coaching on how to talk to children about death. Other times I answer questions ranging from autopsies to how the Medical Examiner’s office interacts with funeral homes. I do my best to make sure that individuals are collected enough after the identification to go back into the world and take whatever their next steps happen to be.

Last week a gentleman who came to identify his mother said that he felt bad that I had to do this kind of work. My first initial reaction was to feel surprised. My corresponding thought was there is no reason why he should feel sorry for me. Doing this type of work is an honor and a privilege. I simply explained to the man that I believe that death is as natural as birth. Some people are there at the beginning of someone’s life and other people are there at the end. At times I feel woefully inadequate in the presence of such extreme loss, but I do my best to be what my mentor, Stephanie Handel, at the Wendt Center for Loss and Healing, has taught me about being an “exquisite witness” to an individual’s grief. At the very least, that person knows I believe their loss is important and has been provided with the resources to obtain additional support in the future.

I feel lucky to be able to experience death in such a direct way. Facing my mortality on a daily basis has a lot of benefits in addition to reminding me to eat my vegetables, say no to drugs, wear safety gear, and avoid befriending people with both anger issues and firearms. I keep things in perspective since few challenges measure up to crisis level after an afternoon at the medical examiner’s office. I have increased gratitude for the people and things in my life that make me feel cared for, safe, and loved.

Becoming a grief counselor and working at the morgue is not the only way to obtain a greater sense of one’s own mortality, although I certainly have a passion for my work. Volunteering for a hospice organization, hospital, nursing home, homeless shelter or food bank, or a children’s grief and loss camp can all be excellent opportunities to help others and engage in self-reflection. Connecting with others and hearing peoples’ stories of loss, and how they make meaning out of that loss, is a necessary reminder of what it truly takes to live.

Liz Kelly, MSW, LGSW is a mental health professional and social worker. She founded the website, www.politicope.com , a mental wellness resource for those living and working in the Washington, DC. She can be reached at politicope@gmail.com .

January 11, 2015

Clown Motel & Ghost Towns

January 7, 2015

Curating a UK Medical Museum: Two Heads are Better Than One

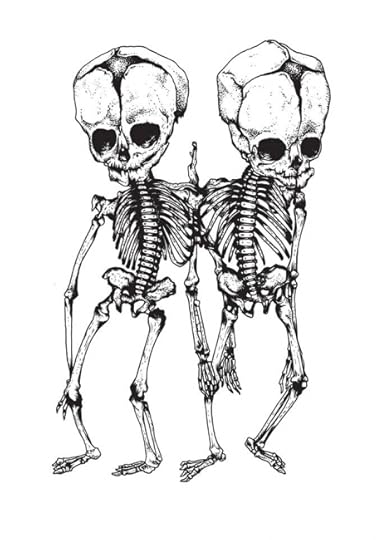

Image: Tony ‘TK’ Smith; specimen TE.5, Barts Pathology Museum

A Brief Introduction

The most recent series of American Horror Story: Freakshow, has been particularly interesting to me as the technical curator of a medical museum in the UK, as well as a fan of the show. In the series two reprehensible characters, “Dr Sylvester Mansfield” and “Miss Rothschild” (Dennis O’Hare and Emma Roberts) attempt to make a living by providing the remains of deceased ‘freaks’ to a museum not unlike my own, loosely based on the famous Mutter Museum in Philadelphia. In order to satisfy the public’s desire for the spectacular display of conjoined twins, deformed adults and more, these two unscrupulous individuals head to a rare but still active freak show in order to murder a few of the hapless ‘performers’ and sell the remains to the curator of the museum in the City for thousands of dollars.

This doesn’t happen in medical museums, particularly in the UK, due to a very stringent set of guidelines provided by a regulatory body: The Human Tissue Authority (or HTA). I can’t really speak for museums at the beginning of the century (as they were unregulated) and it’s common knowledge that anatomy, like many other sciences, has a rather murky past which includes grave robbing and vivisection. However, since 2005 when the HTA was created anything of that sort, if it ever existed, was relegated to the thankfully distant, gruesome past.

Jawbone of a boy whose head was trapped in a Victorian-era printing press.

So why do we have the HTA in the UK when it doesn’t exist elsewhere? It’s because in the 1990s there was a very public outcry about the retention of organs and complete bodies of babies and foetuses uncovered in some UK hospitals (in Birmingham, Bristol and Liverpool). Consent wasn’t given by the parents for this to happen – it simply wasn’t assumed doctors needed to ask for it in those days which was perhaps protection, condescension, or even arrogance – and these parents lobbied the government to form a regulatory body to ensure the practice didn’t continue. It didn’t help that some of these more innocent organ retentions were mixed up in the press with the unethical activities of the sinister sounding Professor Dick van Velzen (at Alder Hey Hospital in Liverpool, my home town) and newspaper headlines seized the opportunity to terrify the public with headlines which harked back to the Victorian era such as “Return of the Bodysnatchers!” and “Ghoulish Malpractice!”

My friend Anna Dhody of Philadelphia’s Mutter Museum recently told me “We do not have anything like the HTA here in the US. Regulations of this kind are done on the state level and the same was true for our Anatomy Acts in the 1800s. We had no country wide Anatomy Act the way the UK did, but some states did pass them…eventually.”

My friend Anna Dhody of Philadelphia’s Mutter Museum recently told me “We do not have anything like the HTA here in the US. Regulations of this kind are done on the state level and the same was true for our Anatomy Acts in the 1800s. We had no country wide Anatomy Act the way the UK did, but some states did pass them…eventually.”

The HTA now governs several different aspects of human tissue usage in the UK: anatomy (dissection in medical schools), post-mortems (autopsy), research, transplant and public display (museums and exhibitions). Having worked within all these areas over the course of my career, the rules and rationale are as familiar to me as the wit of Oscar Wilde, so I’m constantly surprised when others have no idea what I’m talking about when I mention the HTA. The questions often arrive when visitors to the museum ask, ‘Why can’t we go to the upper levels?’ (more on why they can’t in a moment). But of course it’s not clear to most people who haven’t been immersed in death regulations and ethics for their whole adult lives.

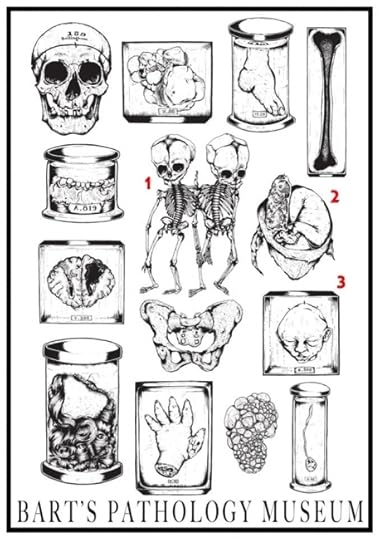

Carla’s Museum Bart’s Pathology, Image: Tony ‘TK’ Smith

So, how to proceed?

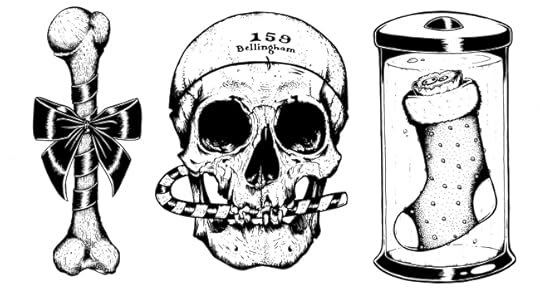

Image: Lauren Hellier “Lozzy Bones

I’m a long-time admirer of The Mutter Museum’s most well-known curator Gretchen Worden, and I’m privileged to be traveling a similar path at Barts Pathology Museum. Our annual visitor numbers have grown from 0 to around 15,000 in the three years I’ve been in my post (despite us only opening for a smattering of evening and weekend events), and we are now creating membership packages as well as merchandise to help with the funding of the museum: posters, tote bags, pens, mugs and more recently these wonderful greetings cards for Christmas via my friend Lozzy Bones!

But the path hasn’t been an easy one. Due to HTA regulations insisting that in the UK the general public cannot see specimens younger than 100 years old without a Public Display Licence I had to re-organise the whole museum as I repaired and recorded all 5,000 anatomical specimens. Now, on the open plan ground floor, all the potted specimens from the deceased are at least 100 years old. That way, the general public can enter the building and browse those specimens, they just can’t ascend the spiral staircase at the back and see the younger pots on the upper two levels up close – it’s a restricted area. That will be set to change in the new year: the best Christmas gift we could have hoped for was the funding to apply for a Public Display Licence which we received from The Medical College of Saint Bartholomew’s Hospital Trust, a registered charity that promotes and advances medical and dental education and research at Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry. We then very recently passed the stringent audits and inspections required for the HTA to actually grant us permission to have the licence.

So things are looking up and in the New Year we can open the second floor to the general public. In the meantime I make the most out of the current situation by informally presenting the specimens which can’t be seen physically (but can be seen via video or photograph as the HTA doesn’t regulate images, only the actual remains) on my YouTube channel’s “A Potted History Of…” play list.

However, there is still a sense of horror and fear in the UK at the retention and display of specimens of deceased babies in particular, and even when they’re over 100 years old, or simply drawn in pen or pencil, they remain truly controversial. For example, our recent attempt at the poster below caused the HTA to advise us to remove the three foetal specimens, labelled:

This is despite the fact that these are drawings (not the actual specimens or even photographs) and they are of specimens over 100 years old. This illustrates that it just isn’t as clear cut as it should be, even with the regulations in place, and it’s even been suggested I put a warning sticker on some specimens. Of course we medical museums do have a responsibility to the public – we need to ensure visitors don’t leave traumatised! But at the same time, there is something to be said for people being made fully aware of that possibility before they enter a medical museum, regardless of which specimens they see. It’s not for me to say what is ‘more’ or ‘less’ disturbing – I believe it’s too subjective. If I was to label only those pots I thought were disturbing I’d be repeating practices in 19th and early 20th Century anatomy museums and peripatetic curiosity shows which hid their titillating specimens behind velvet curtains. To me that seems counterproductive as they become more titillating, and perhaps the only ones the public would want to see!

This is despite the fact that these are drawings (not the actual specimens or even photographs) and they are of specimens over 100 years old. This illustrates that it just isn’t as clear cut as it should be, even with the regulations in place, and it’s even been suggested I put a warning sticker on some specimens. Of course we medical museums do have a responsibility to the public – we need to ensure visitors don’t leave traumatised! But at the same time, there is something to be said for people being made fully aware of that possibility before they enter a medical museum, regardless of which specimens they see. It’s not for me to say what is ‘more’ or ‘less’ disturbing – I believe it’s too subjective. If I was to label only those pots I thought were disturbing I’d be repeating practices in 19th and early 20th Century anatomy museums and peripatetic curiosity shows which hid their titillating specimens behind velvet curtains. To me that seems counterproductive as they become more titillating, and perhaps the only ones the public would want to see!

To facilitate an objective UK wide discussion about these particular specimens I have been working with staff at UCL Pathology Collections and medical illustrator/researcher Dr Lucy Lyons after we were awarded funding for a project entitled Drawing Parallels: Artistic Encounters With Pathology. The purpose of these “slow-looking” drawing and discussion workshops is to get to the root of what it is that makes people feel so uncomfortable about some remains compared to others: old vs. young, skeletal vs. soft tissue etc. The results so far have been fascinating and will appear in a future paper.

The above illustrates that in the UK the desire to engage the public with these wonderful and valuable specimens requires tact, responsibility, tenacity and the ability to think outside the box. In an alarmingly familiar MO to mine Gretchen Worden was said to display “a mischievous glee as she frightened David Letterman with human hairballs and wicked-looking Victorian surgical tools, only to disarm him with her antic laugh.” I hope I achieved the same when I was recently on the UK’s Alan Titchmarsh Show with tapeworms, a syphilitic skull, slices of liver and a hand with leprosy.

The above illustrates that in the UK the desire to engage the public with these wonderful and valuable specimens requires tact, responsibility, tenacity and the ability to think outside the box. In an alarmingly familiar MO to mine Gretchen Worden was said to display “a mischievous glee as she frightened David Letterman with human hairballs and wicked-looking Victorian surgical tools, only to disarm him with her antic laugh.” I hope I achieved the same when I was recently on the UK’s Alan Titchmarsh Show with tapeworms, a syphilitic skull, slices of liver and a hand with leprosy.

Conclusion

My aim with this article is not to paint the HTA as some sort of Victorian ‘Society for the Suppression of Vice’ because the simple fact is we need regulations when it comes to contentious materials. It has been said that any civilised society is measured by how it treats its dead [1] and this is why HTA inspections are imperative. Recently a story focused on 100 brains which went missing from the University of Texas – under HTA governance this would be an absolute scandal in the UK and staff responsible for the remains would face up to three years in prison.

Of course the UK and the US has much in common when it comes to other human remains, for example in the funeral industry: embalmers, funeral directors and pathologists need to be regulated too. The same goes for careers such as Anatomical Pathology Technology: ‘morticians’ like me who are certified by the RSPH and affiliated with the AAPTUK. This ensures that those who simply take a fancy to something like embalming can’t just pick up a trocar and a box of Dodge cosmetics and get to work. (However, one scandalous US case which illustrates the state-wide inconsistencies in post-mortem regulations is that of Shawn Parcells, the ‘forensic expert’ in the Michael brown case. This shocking lack of formal training is utterly illegal in the UK and this simply would not happen here.) Currently there is a growing death-positive movement in the Western world (“About time” says the dormant goth in me who’s been dying to make herself known) and this is of course a good thing when it pushes the general public to question the end-of-life care of relatives, to not be taken advantage of by unscrupulous undertakers at a difficult time and instead do their research, or to really live every day to the full by being aware of their own mortality. But it can’t make experts of us all and there is a danger for those unregulated professionals to use the topic’s popularity to their advantage (just like the 19th Century quacks who were instrumental in the closure of anatomical museums many years ago [2]) I’ve heard some fuzzy logic from those dilettantes who dip their toes into the murky waters of death which, even those of us who have ‘earned a chart’, find difficult to navigate (as I’ve tried to illustrate, above). I’ve heard the reason “Well we all die, therefore we all have expertise in the topic and have a right to say so.” Unfortunately one can no-more use that logic than one can say “We were all born – let’s all now be midwives. Someone pass me the hot, wet towel and the kitchen scales while I get to work!”

Image: Carla Valentine and Barts Pathology

So we need regulations as much as they make life a bit more difficult. We need to make sure that in return for the wonderful gifts bestowed to us in our incredible museums or dissection rooms we promote dignity and respect, at the same time as trying to somehow make the specimens relevant and interesting. One article said: “Ms. Worden used humour and charm to ease viewers past the initial gawking or revulsion the museum’s collection might trigger. There was a serious message behind her sometimes madcap affect: that the human body is not to be feared or loathed, even when horrifically damaged or monstrously distorted.”

Similar to Gretchen Worden I feel like I have to come at the issue with two different heads on: one professional, qualified and driven – attempting to educate and promote the value of these specimens for future generations. The other passionate, curious and irreverent – attempting to tie the specimens in with popular culture and engage the public. In other words, I feel like THIS!

Image: Lozzy Bones

Refs:

[1] “The Treatment of Human Remains”, K. S. Satyapal. South African Journal of Bioethics and Law, June 2012, Vol. 5, No.1

[2] “Indecent and Demoralising Representations”: Public Anatomy Museums in mid-Victorian England, A. W. Bates, Medical History, Jan 2008, Vol. 52, No. 1

January 4, 2015

A Field Trip to North Carolina’s Death Chamber

I was promoted to Director of Mental Health Services for the North Carolina’s prison system in September 2006. During my tenure, I served as ringmaster for more than a hundred clinicians who tended to the psyches of 38,000 incarcerated souls… including those on Death Row.

I was promoted to Director of Mental Health Services for the North Carolina’s prison system in September 2006. During my tenure, I served as ringmaster for more than a hundred clinicians who tended to the psyches of 38,000 incarcerated souls… including those on Death Row.

North Carolina carried out its last execution at Central Prison not long after I assumed my role. Although the death penalty remains on the books, for the past seven years there has been friction between the legislature and the state medical board as to whether executions would be allowed to resume (you see, the medical board now prohibits any licensed physician from being in attendance at an execution, and without a doctor, the condemned can’t be declared dead, and the show can’t go on).

Although I could see the sun brightly glistening off the dew-bespeckled concertina wire each morning from my corner office overlooking the complex, and despite the number of hours I’ve spent on the cellblocks, I had never seen the actual execution suite. I wasn’t even certain where, in the labyrinthine maze that is the prison, that room is located.

Recently, I asked the Warden if he’d show me the death chamber when he had a moment. “How ’bout in ten minutes?” he replied.

Prior to the early 1980s, executions were conducted in the ‘old section’ of the prison – the nucleus of which dates to the 1860s. Just over 30 years ago, the current execution suite was constructed in the newer part of the front building, which I learned happens to be directly over the Warden’s head as he sits at his desk in his office.

The Warden and I walked to the elevator past his secretary’s desk a few steps away. I had seen this elevator in the corridor next to the administrative wing for years, but never knew to where it lead. We went up one floor and exited onto a short hallway, a doorway being directly across from the elevator. There was no one around, and it was entirely quiet. The floor and walls were clean, brightly lit, and with a hint of institutional antisepsis. I sensed a yellowish tint to everything from the paint. To our left at the end of the short hallway was a room containing a black telephone. It is on this phone that last minute calls from the courts are received, if they are coming at all. Those calls can order a stay of execution at the 11th hour, sometimes when the condemned is already strapped to a gurney.

To our right, the short hallway curved leftward and out of sight.

Initially we proceeded through the doorway directly across from the elevator, which I found leads into the execution witnesses’ room.

Witness Room, Pre-Yellow Paint. Via AP.

It’s an oddly-shaped and cramped little quarter. Three rows of plastic chairs remain lined up facing a window overlooking the site of the gurney, even though no execution has taken place in years. That same yellowish tint was present, and the ventilation seemed poor and the room stuffy. I can imagine when filled with a dozen witnesses, it gets hot and muggy in there quickly. And in these cramped quarters, journalists, official observers, and those from both the victim’s and convict’s families sit almost knee to knee.

That must make for some uncomfortable small talk before the main event.

Back outside the witnesses’ room, we turned and went down the hall, around the corner, and entered what is a technician’s room. This vestibule – once again, cramped and oddly shaped – also has a window, much smaller, overlooking the site of the gurney from a different angle. During an execution, it is in this second cubbyhole that a physician and technician sit and monitor the EKG attached to the condemned for telltale signs of death.

[There are also a number of buttons on a console on the wall that have nothing to do with EKGs, but more on that in a moment.]

We exited the technician’s room and turned to the left, walking in essence in a circle around the death chamber, which is roughly in the middle of this layout.

The next stop, only feet away, was the prisoner holding area. When someone is under death watch immediately prior to execution, they are brought from death row proper to a cell which is spitting distance from the chamber itself. Paradoxically, there are five holding cells in a row, though it’s unlikely that there would be more than one inmate in any of them at a given time (I don’t think this state has ever performed multiple executions in one day).

Continuing to the left, we came finally to the entrance to the death chamber. There is ‘the’ gurney parked in the hallway just outside the portal, neatly fitted with clean white sheets as if ready to use in a few minutes. Stepping inside the room, there are small marks on the floor to show officers where to park the gurney once the condemned has been strapped into place so that everything is visible to the witnesses and the physician and technician. The death chamber, like the witnesses’ room, is not a perfect rectangle, but instead an odd rhomboidal shape, probably because the building was retrofitted for this purpose long after construction. A thin yellowish curtain – there’s that color again – hangs from the ceiling so that staff can set up the gurney before revealing it to observers once everything is in place.

Gurney in Place, As Seen From the Witness Room

The biggest surprise of my tour? I had been under the impression that the current death chamber was used only for lethal injections. But it turns out that until the late 1980s, it was also the gas chamber! I was astounded to learn this because, honestly, the windows into the technician’s and witnesses’ rooms don’t look very thick. But sure enough, the sole door leading into the small room in which the executions take place is constructed airtight like those on a submarine, with steel bulkheads, heavy thick rubber gaskets, and a hatch wheel. Plus there are vents visible in the ceiling of the chamber through which the cyanide gas goes out to the roof.

Having now seen the setup, I am not certain that I’d want to be a witness with just a pane of glass separating me from instant, aerosolized death.

And those buttons on the console in the technician’s room? Those controlled the flow of gas, but it was too much trouble to take them out when lethal injection became the norm, so the piping for the potassium cyanide still exists and just isn’t used.

I hope they’ve removed and stowed the canisters. I didn’t ask.

Given the difficulty that states have encountered in obtaining the necessary chemicals for lethal injection of late – and our current administration’s desire to resume executions – there is talk that they will employ other means to clear the (no other way to say this) backlog. I doubt seriously that returning to poison gas would be politically palatable. I’m told that Old Sparky (the chair) is still stored somewhere in the bowels of the prison, so I wonder if they might be re-wiring the chamber shortly to accommodate the extra voltage needed.

Not sure, but stay tuned.

December 18, 2014

Dad’s Corpse in the Spare Bedroom

Last week saw the conclusion of the case of Kaling Wald, a Hamilton, Ontario woman who faced legal troubles after letting her dead husband’s body remain locked in the couple’s spare bedroom for six months after he died there last year. By all accounts, Kaling had a sincere religious belief that her husband Peter Wald would return from the dead. So sincere in fact, that when the 53 year old died at home in March of 2013, she left him on his deathbed to rot and didn’t tell anyone except the couple’s five children aged 11 to 22 and their seven adult roommates. What Kaling was less certain of was when Peter would return from the dead. Not wanting to take any chances, she was in it for the long haul and did not want the kids seeing what advanced decomposition looks and smells like in the meantime. So she padlocked the bedroom and placed duct tape on the air vents for good measure. Six months later in September of 2013, the home went into foreclosure. When the sheriff came by, he found the body in such a decomposed state that it couldn’t be identified by photograph.

Last week saw the conclusion of the case of Kaling Wald, a Hamilton, Ontario woman who faced legal troubles after letting her dead husband’s body remain locked in the couple’s spare bedroom for six months after he died there last year. By all accounts, Kaling had a sincere religious belief that her husband Peter Wald would return from the dead. So sincere in fact, that when the 53 year old died at home in March of 2013, she left him on his deathbed to rot and didn’t tell anyone except the couple’s five children aged 11 to 22 and their seven adult roommates. What Kaling was less certain of was when Peter would return from the dead. Not wanting to take any chances, she was in it for the long haul and did not want the kids seeing what advanced decomposition looks and smells like in the meantime. So she padlocked the bedroom and placed duct tape on the air vents for good measure. Six months later in September of 2013, the home went into foreclosure. When the sheriff came by, he found the body in such a decomposed state that it couldn’t be identified by photograph.

The city’s hometown paper had a field day with this story. An article in The Hamilton Spectator written shortly after the discovery of the body bears the headline: “How does a man lie dead in a house for months on end?” Of course, the question was not being asked in the literal sense. The Spectator wasn’t looking to publish an article detailing how corpse decomposition plays out in a home environment. What the author was likely trying to do was express a bit of subtle outrage. How dare this woman leave her husband’s body to rot in a bedroom? Why did nobody intervene to stop this atrocity? Not everyone shared this restraint in expressing their views however. In an apparent act of vandalism, Fred’s minivan was damaged after the news came out. Even PETA has gotten in on the action with a local billboard referencing the story.

via PETA

There’s no denying that there is a certain ickiness to the sight and smell of a decomposing body. When I asked Josh Slocum, Executive Director of the Funeral Consumers Alliance -a watchdog group for the funeral industry similar to Consumer Reports- about what a body left on a bed in a room with no ventilation might look like a few months later, his response was “in a word: ‘unpleasant’”. He gave the example of a dead animal left under a porch to aid me further in visualizing the spectacle. He also pointed out that bodily fluids can be highly damaging to furniture and flooring. The smell of a dead human is nearly impossible to remove from a room once the fluids start seeping into the floor (in cars he says the smell is basically impossible to remove).

Be that as it may, we are still talking about property damage. In the home of a stranger no less. With certain rare exceptions (a 53 year old diabetic who died at home not typically being one), a dead body is not a health risk to anyone. Per the coroner that examined Peter Wald’s remains: “There was nothing in the examination that would suggest criminal activity or public health concerns”. There’s a million ways in which someone might cause harm to the inside of their house. Would that lead a random reasonable person to become angry enough to smash their car window? Would any editor of a newspaper commission the writing of several articles about it? I doubt that very much. Of course, this is not to say that corpses ought to be fair game for everyone’s whims. For example, it certainly makes sense to be respectful of the feelings of family and friends of the deceased when making final arrangements and to adhere to any legal directives the person made while living. However, every indication is that the residents of the Wald household were all on board with the arrangement, so none of that would appear to apply here.

via AAA Crime Scene Clean Up

As if all these events weren’t traumatic and stressful enough for the family, the following January the police came and arrested Kaling Wald. There was never any evidence of foul play with regards to her husband’s death, but the prosecutor decided that charging her with “neglect of duty regarding a dead body and offering an indignity to a body” under section 182 of Canada’s criminal code would be appropriate. While the charges are fairly rare, the maximum punishment of five years imprisonment for this victimless act is on par with possession of child pornography. It should be noted that there are many jurisdictions here in the US that share this obsession with respecting the sensibilities of cadavers. Slocum informed me that Massachusetts forbids funeral directors from using “profane, indecent or obscene language” in the presence of the dead.

Almost a year later, this bizarre and unwarranted legal exercise looks like it has come to an end. Per the National Post:

Ms. Wald pleaded guilty on Monday to failing to notify authorities of his death from disease — an offence under the Coroner’s Act….Those charges were withdrawn in the “11th hour,” and replaced with the Coroner’s Act charge, Ms. Wald’s lawyer Peter Boushy said.

Ms. Wald was sentenced to 18 months probation with counselling from a Christian counsellor.

However, the judge had some very stern parting thoughts for Kaling Wald predicated on nonexistent “public health concerns”. The Spectator adds:

Kaling – who has no past criminal record – had her sentence suspended and was put on 18 months of probation and ordered to seek counseling around the “public health concerns” of the incident.

“Your belief that your husband would resurrect is not an issue,” Superior Court Justice Marjoh Agro said at her plea Monday.

“This is not about your religious beliefs. It is about your safety, the safety of your children and the safety of the community at large.”

Kaling Wald’s conviction that a her husband’s dead body must be locked up in a room for resurrection that will never happen is deeply misguided. However, nobody is really being injured by this corpse’s decomposition any more than they are by the millions of other corpses decomposing in other places. But yet people will laugh at her and say Of course he’s not coming back, he’s dead!

As a society though, have we really come to terms with all the implications of what “he’s dead” actually entails with regard to a human body? It does not appear that we have. If we did, then “offer[ing] any indignity to a dead human body or human remains” wouldn’t be the legal basis for potentially sending someone to prison in an industrialized country. The sight of Peter Wald’s corpse rotting on his bed might be be unseemly to most onlookers. But is he in any position to have an opinion on the matter? Of course not. He’s dead. The only parties that have feelings that can or should be taken into account are those of his living family members.

At the end of the day, which is causing the greater harm here: Kaling Wald’s mistaken belief in resurrection? Or the notion of protecting dead bodies from the “indignities” that the living might inflict upon them?

Simon Davis is a columnist for VICE where he writes a weekly column about death called “ Post Mortem ”. You can follow him on Twitter here .

December 16, 2014

Ask a Mortician- Really My Mother’s Ashes?

December 11, 2014

Very Merry Morbid Holiday Gifts, Under $25

via Cabinet of Curiosities

‘Twas the night before Christmas,

And all through the house.

Not a creature was stirring,

Except for the person stuffing the stocking of someone they love with a death positive gift that shows how much they support that person’s completely normal interest in mortality.”

*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*

Hello deathlings! I’m just going to say it: don’t get someone socks for the holidays. (Unless they’re anatomical or skeleton-themed socks. In which case go for it.) Instead, get them something morbid that they can enjoy all year round.

Since I myself am terrible at gifts, I want to help you not be terrible at gifts by finding things your loved ones are guaranteed to adore. In fact, I’m SO sure they’ll love these items, if they don’t, I’ll let you send them to me. *wink*

Disclaimer: I know some of these are North America-centric, because the price of international shipping is “your firstborn childe.” Sorry guys!

Click on each item for a bigger look.

So, yes. Ok. This is my own book. I understand you can’t put your own book in a “must have” holiday list. That’s just obscene. But don’t you want your loved ones to face their mortality this holiday season? ‘Tis the season to ACCEPT DEATH. Smoke Gets In Your Eyes, $19-24.

Who is this? Who is my squishy? Who is my squishy little reaper? Reapykins? Reapypoo? Deathmeister? Who’s gonna die? Who’s gonna die? Yes you are. Oh yes you are! Mini Squishable Grim Reaper, $19.50

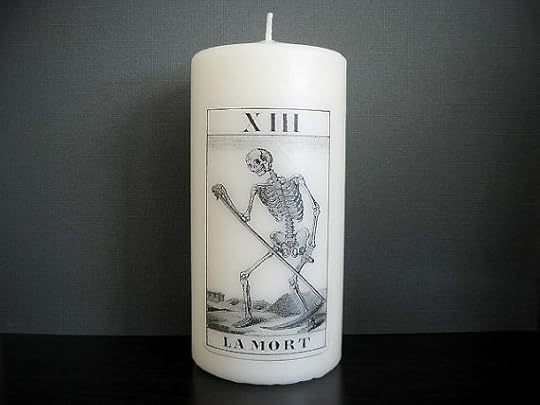

Erica at Burke & Hare Co has an eye for the effortlessly macabre. Her candles (I’ve had many) last forever. My morbid gift selections are the Tarot Death Candle, $15 and Skull Plate, $18.

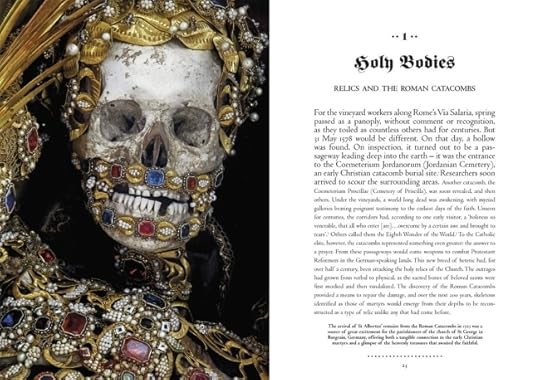

You know how Catholic Church used to decorate their martyr’s skeletons with gold lace and precious jewels and display them to the faithful? Well now you do. Order-member Paul Koudounaris has access to photograph some of the most bonkers things, his book Heavenly Bodies, $24.59 is an elegant addition to any stocking of woe.

You know how Catholic Church used to decorate their martyr’s skeletons with gold lace and precious jewels and display them to the faithful? Well now you do. Order-member Paul Koudounaris has access to photograph some of the most bonkers things, his book Heavenly Bodies, $24.59 is an elegant addition to any stocking of woe.

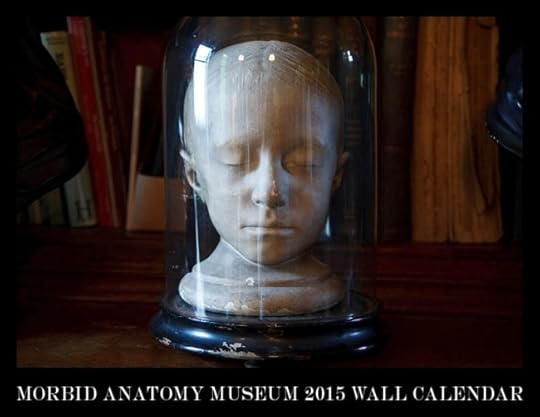

If you want to give them something useful, look no further than Morbid Anatomy’s 2015 wall calender, $20. The pictures from hidden museums are complemented by noting the REALLY important dates (like Edward Gorey’s birthday).

If you want to give them something useful, look no further than Morbid Anatomy’s 2015 wall calender, $20. The pictures from hidden museums are complemented by noting the REALLY important dates (like Edward Gorey’s birthday).

Death Salon and the Order have tote bags! Wear them and prepare to answer the horrified questions of the pearl clutchers in your town. Yes Virginia, we do think about death. Totes, $15

This little cutie right here. Here’s your assignment: buy 200 of these, fill an entire Christmas tree with crow skulls. Don’t waste your time on all that yuletide crap. Suck it Santa. Ho ho crow skull.

This little cutie right here. Here’s your assignment: buy 200 of these, fill an entire Christmas tree with crow skulls. Don’t waste your time on all that yuletide crap. Suck it Santa. Ho ho crow skull.

Ok, I know I said $25 is the budget, and this is $27. But if you want a Lady Skeleton Cameo on a apron, you want a Lady Skeleton Cameo on an apron. Don’t you see? The heart wants what it wants. Fly free, heart!

Ok, I know I said $25 is the budget, and this is $27. But if you want a Lady Skeleton Cameo on a apron, you want a Lady Skeleton Cameo on an apron. Don’t you see? The heart wants what it wants. Fly free, heart!

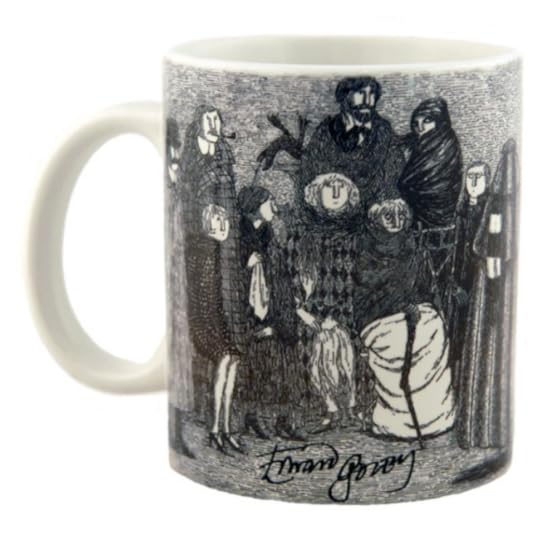

I’m not supposed to be buying gifts for myself. This is for other people, Caitlin! But this Edward Gorey mug, $12.50, from his book the The Awdry-Gore Legacy, might be a Secret Santa gift to me. That’s right. I’m my own Secret Santa.

I’m not supposed to be buying gifts for myself. This is for other people, Caitlin! But this Edward Gorey mug, $12.50, from his book the The Awdry-Gore Legacy, might be a Secret Santa gift to me. That’s right. I’m my own Secret Santa.

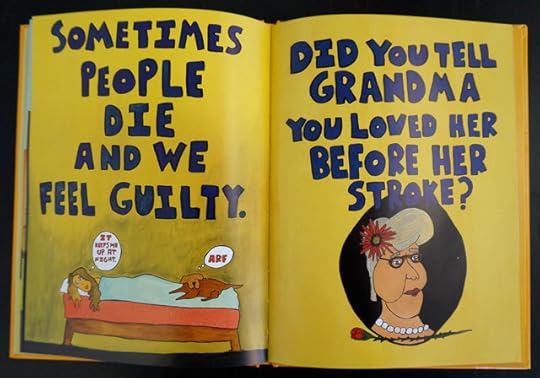

Ken Tanaka’s book Everybody Dies, $10 has it all. The straight talk about death (“cute animals die, and so do scary ones”), adorable pictures, and a relatable message. DEATH.

Ken Tanaka’s book Everybody Dies, $10 has it all. The straight talk about death (“cute animals die, and so do scary ones”), adorable pictures, and a relatable message. DEATH.

For the book lover (don’t you love books? WHY DON’T YOU LOVE BOOKS?) there is a plethora of additional options on the Order’s reading list. Happy Holidays everyone, and remember that family gatherings are an excellent time to discuss your wishes for your death care.

Caitlin Doughty's Blog

- Caitlin Doughty's profile

- 8410 followers