Caitlin Doughty's Blog, page 30

May 10, 2017

Pop Goes the Reaper! – May 2017

Get ready to explore your mortality through the games, movies, books and shows our contributors are currently consuming. Find new things to read, watch, or play – on your own, or with friends and family of all ages.

Gabby’s Picks:

Beautiful Bones: Sakurako’s Investigation — Anime

Beautiful Bones: Sakurako’s Investigation (櫻子さんの足下には死体が埋まっている) is a gorgeous anime TV series that follows Sakurako Kujou, an eccentric osteologist, and her highschool-aged sidekick Shoutarou Tatewaki as they happen upon crime scenes, solve mysteries, and ultimately help each other mourn their lost loved ones and overcome their own death anxieties. I’ve been binge-watching Beautiful Bones on CrunchyRoll and though I still have a ways to go, so far I’ve been head-over-heels in love with Sakurako and her beautiful collection of bones.

Watch Beautiful Bones: Sakurako’s Investigation on Hulu or CrunchyRoll.

Night in the Woods — Videogame

Night in the Woods is a single-player adventure game for PC, Mac, and Linux that stars Mae, a college dropout who has returned to her hometown of Possum Springs. Now living in her parents’ attic, she must readjust to small town life, but soon her and her friends uncover a dark mystery that leads them into woods nearby. Night in the Woods deals with death in a huge variety of ways — from mourning a lost one, to mourning what your small town once was, to even explicitly dealing with the topic of death and sacrifice at times. Night in the Woods’ greatest strength is how well-written the characters are and how relatable they all feel— Mae’s mother in particular reminded me of my own mother (who died not too long ago) and Night in the Woods has been playing a vital role in how I mourn her. It’s an incredibly special game that I have so many feelings about and cannot recommend enough.

Get Night in the Woods here.

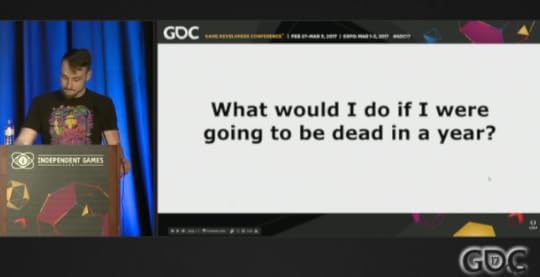

The Last Game I Make Before I Die: The Crashlands Postmortem — YouTube Video / Videogame

Crashlands (PC/Mac/iOS/Android) is a crafting adventure game developed by a trio of brothers (and their studio Butterscotch Shenanigans) shortly after one of the brothers Samuel Coster was diagnosed with cancer. At the 2017 Game Developers Conference (GDC), Samuel presented a postmortem of Crashlands focusing on how dealing with cancer and confronting his own mortality affected the development of the game. It’s a simultaneously heartbreaking and triumphant talk that was met with a much-deserved standing ovation, and you can watch the entirety of it on GDC’s YouTube channel. Even if you’re not interested in videogames, I still highly recommend checking it out — Samuel is a fantastic presenter.

Watch The Last Game I Make Before I Die: The Crashlands Postmortem on YouTube.

Krista’s Picks:

Chef’s Table – Alex Alta (Season 2) – Documentary Series

Chef Alex Atala is bringing death awareness to a place where we deny death the most: the table. I was introduced to Chef Atala while binging the Netflix series, Chef’s Table. Wearing his iconic “Death Happens” shirt, Atala discusses his attempt to reconnect both chefs and diners to the meat that we eat. Most chefs don’t meet the meat they cook, something that greatly disconnects them from death in the kitchen. Anthony Bourdain admitted in A Cook’s Tour that he hadn’t witnessed an animal’s death-for-food until he was 44. Chef Atala wants to change the way we feel about the culinary experience: “My message is to remember that we are all connected to the meat we consume, to never forget that to eat meat means that death happened.” Chef Atala’s episode is not to be missed.

Watch Chef’s Table: Alex Alta on Netflix.

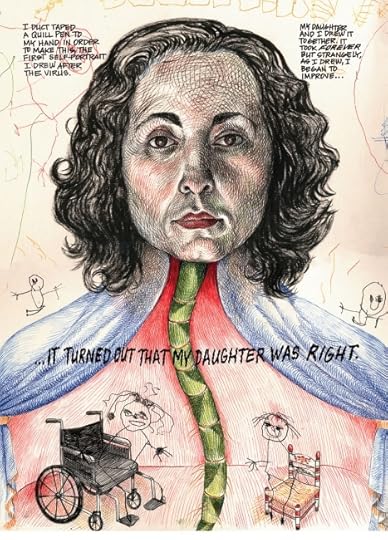

My Favorite Thing is Monsters – Graphic Novel

My Favorite Thing is Monsters – Graphic Novel

When I opened up Emil Ferris’ must-read debut graphic novel My Favorite Thing is Monsters, I was socked in the face with unrelenting nostalgia that poured from a kaleidoscopically constructed montage of pulpy perfection. Ferris’ masterpiece, set in 1960’s Chicago, is vesseled in the journal of Karen, a 10 year old lone wolf who thinks of herself, and draws herself, as a werewolf. Her seemingly mundane life is thrown for a loop when her friend Anka, an aging Holocaust survivor who lives upstairs, is murdered and Karen sets out to find the killer. The exploration of “monstrousness” and images of death in this masterpiece are grown of Ferris’ own life experiences; when Ferris was in her 40s, she contracted West Nile Virus and had to learn to draw all over again. The virus gave Ferris wild hallucinations, and these experiences are visible in the incredible scope of her illustrations. Ferris discusses meeting death in a virus induced mirage– “The angel of death came to visit and the angel of death as I saw it in my fever was a very big, 1940s kind of a gray/teal/blue filing cabinet, and it was sort of a bureaucrat and it just came into the room…” [death does often seem like a looming bureaucrat…]

Writing My Favorite Thing is Monsters was Ferris’ response to her brush with death, and it serves as a comforting reminder to the reader that we all face some sort of dark adversity. “I always felt like [monsters] were kind of heroic because they were facing something,” says Ferris “Becoming a monster sometimes isn’t a choice that you have. We’re all that; we’re all ‘the other’ in one way or another.”

My Favorite Thing is Monsters is available digitally and in print.

Extremis – Documentary

In and out of emergency rooms and nursing facilities, my grandmother’s last breath escaped her under fluorescent lights, wrapped in threadbare hospital sheets. The most painful part of the end of her life was her lack of agency because of her dementia. Her children bickering over DNRs and life support were among the last earthly words she heard. The Netflix documentary Extremis, in a breathtaking twenty-seven minutes, tells the story of people who shared my grandmother’s experience. It takes a raw approach to the doctor’s dilemma and is fearless, showing every emotion a family moves through while deciding on a good death for their loved one. Watching this takes some mental preparation, but I can’t recommend this documentary enough.

Watch Extremis on Netflix.

Doctors – Graphic Novel

Hate that Clive Custler novel your grandpa got you for Christmas? Have an affinity for graphic novels and death positivity? Excellent! Run to your neighborhood comic book store (or to your amazon app) and grab Doctors by Dash Shaw. Doctors is a tale of modern necromancy, bizarre afterlives and letting go. It’s guaranteed to quench your thirst for death and weirdness.

You can get Doctors at your local comic book store or Amazon.

Myeashea’s Picks:

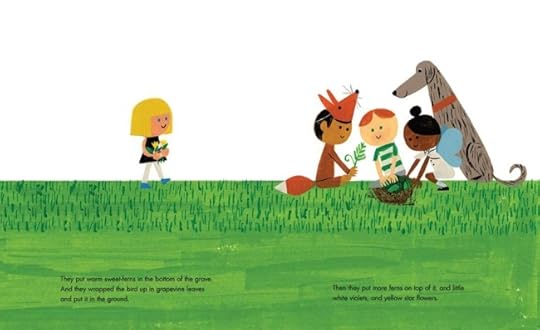

The Dead Bird – Children’s Book

“The bird was dead when the children found it.”

These are the opening words to Margaret Wise Brown’s, classic children’s book, “The Dead Bird.”

The illustrations in the most recent edition, by Christian Robinson, are bright and vivid, in contrast to Brown’s use of simple, and direct language to discuss death – biologically, ritually, and emotionally.

The children are clearly in the midst of intense play in the middle of a beautiful park on a gorgeous day when they encounter death. Through this tiny bird, the children express sorrow that the bird is no longer a part of the world, but proceed to emulate the burial practices and customs with which they were familiar. Brown’s book provides brief and simple explanations, yet is free from taboo and mystery. The children encounter death, mourn, honor, and move on. It isn’t a traumatic event.

The Dead Bird is available on Amazon.

Bill & Ted’s Bogus Journey – Film

Bill & Ted’s Bogus Journey – Film

Some may be tempted to argue with me about the brilliance of the Bill and Ted’s most excellent sequel, more formally known as their Bogus Journey, but their encounter with Death should not be overlooked.

In the follow- up film, evil Bill and Ted robots are sent from the future by their nemesis to kill good Bill and Ted in an attempt to change the future and wipe out the utopian society based on their success as rockstars in the band Wyld Stallyns.

Now dead and running around the afterlife, Bill and Ted are frantically trying to figure out how to not be dead. They are seeking the power to determine their own fate and not be dead.

While this may seem silly, throughout human history, Bill and Ted’s dalliance with death highlights the anxiety and disquiet that many feel when thinking about or examining death.

In a totally goofy scene, they challenge Death to a game. If they win, they get to be alive again, but if they lose, game over.. Challenging Death to a game is a theme that has been repeated throughout pop culture for a while. However, the modern imagery of man versus death in a game comes from the 1957 Ingmar Bergman film Seventh Seal. Bergman was influenced by a 15th century art piece by Albertus Pictor which featured Death playing a game of chess.

In Bergman’s film, Death comes for a knight along a rocky beach. The knight tells Death that his body is ready to die, but he is not. As Death approaches him, the knight challenges him to a game of chess. The knight is hoping to stop death, or at least hold him off for awhile. He’s trying, futilely, to outsmart Death.

While Bergman’s knight was unsuccessful, the scene in Bill and Ted pays homage to Bergman’s deeply philosophical film. Yet in a humorous twist, they totally win several times! Perhaps there is a lesson that could be garnered from their winning, such as heart over brain, or passion over wit; but there is something incredibly gratifying about hearing Death say, “You sunk my battleship.”

Bill & Ted’s Bogus Journey is available on Amazon.

Pushing Daisies – Series

One of my most favorite, now cancelled, television shows was about an adorkable, baker named Ned.

“My name is Ned. I live a simple life. I wake pies and make the dead. That was creepy. I make pies and wake the dead…”

Before he was known for his cinematic, dark series about the cannibal, Hannibal, Bryan Fuller produced a charming, visually captivating, short-lived (excuse the pun) sitcom, Pushing Daisies. Lee Pace starred as an awkward, nervous pie-maker, who discovers he has the power to wake the dead. However, there’s a couple of strings attached to this not-so-super power: 1) once he touches a dead person to bring them back to life, he can never touch them again or they’ll die permanently and 1) if he keeps the person alive longer than one minute, another random person must die in their place.

Through a series of weird circumstances, he ends up partnering with a private investigator, and his childhood crush, “Charlotte Charles” that he brought back from the dead, to solve crimes.

However, what I found most intriguing about this super saturated, hyper colorful, world of the living and dead, is that when the dead are awakened, they are always a bit absurd, comical.

The ludicrous deaths and candy coated visuals that defined the series, are so endearing and entertaining that you forget that the show is about death and dying.

“Well, I suppose dying’s as good an excuse as any to start living.”

— Charlotte “Chuck” Charles

Pushing Daises is available in several formats on Amazon.

The Clairity Project – YouTube

The Clairity Project – YouTube

“So I’m dying. Faster than everyone else,” Claire Wineland giggles at the start of her YouTube episode titled “Life Expectancy.”

Claire is 19 years old, has cystic fibrosis, and is using social media to have frank conversations about death and dying. Her YouTube channel, The Clairity Project, is an open invitation for people to ask all the questions that they’ve been too scared to ask about sickness and death. Claire isn’t shy when addressing topics ranging from sex and relationships to her own illness and challenges. Her conversational and energetic vibe helps to make difficult and sometimes taboo conversations easier and engaging without romanticizing or idealizing the difficulties and fears that many people experience when faced with mortality.

Watch The Clairity Project on YouTube.

Sarah’s Picks:

Buffy the Vampire Slayer – The Body (Season 5) – Series

Buffy the Vampire Slayer – The Body (Season 5) – Series

There’s been a renewed interest in one of my all time favorite shows, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, as the show turned twenty this year (OMG I AM AN OLDS NOW). Buffy was culturally significant in so many ways – it was feminist af, its signature writing influenced our language, and it depicted a same sex relationship during a time when seeing two girls kiss on TV was a rarity (I still have my collection of Tara action figures!). With standout episodes like Hush, Once More With Feeling and The Body, Buffy repeatedly elevated the medium of television.

There’s a ton of deathiness to delve into throughout the show’s six seasons, as Buffy and the Scoobies face countless supernatural deaths, and save us from the apocalypse – a lot. However, the episode The Body is arguably the most accurate depiction of death and grief in a series. It is full of terrible, yet beautiful moments that perfectly illustrate the experience surrounding a death – none of these more so than Anya’s heartbreaking monologue. It is here that she gives voice to all of us, as we struggle to comprehend death itself – “What’s going to happen? What is expected of us? Are we going to see the body? Will we be in the same room with a dead body? Are they going to cut the body open?”

Watch Buffy the Vampire Slayer on Hulu.

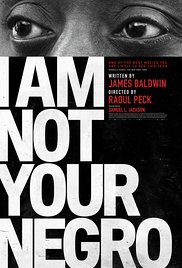

I Am Not Your Negro – Documentary

I Am Not Your Negro – Documentary

I recently attended a screening of this Oscar nominated documentary, featuring and based on the work of American writer and social critic, James Baldwin.

The doc is a profound and vital examination of American identity, which delves into who we are as a nation, by examining and reflecting on our history. Underneath it all, our death-phobic society is exposed, and we are forced to confront our own fears and complicity.

Each of us contributes to this national identity and culture through our own beliefs and notably, fears. In particular, our fear surrounding death can shape our behavior and subsequent actions in unexpected and often disturbing ways, (see How the Unrelenting Threat of Death Shapes Our Behavior) Viewing I Am Not Your Negro is a way to begin examining those fears and beliefs by attempting to understand ourselves – both as individuals and as a nation – beginning with taking responsibility for our fear of death and “confronting with passion the conundrum of life.”

“Life is tragic simply because the earth turns, and the sun inexorably rises and sets, and one day, for each of us, the sun will go down for the last, last time. Perhaps the whole root of our trouble, the human trouble, is that we will sacrifice all the beauty of our lives, will imprison ourselves in totems, taboos, crosses, blood sacrifices, steeples, mosques, races, armies, flags, nations, in order to deny the fact of death, which is the only fact we have. It seems to me that one ought to rejoice in the fact of death – ought to decide, indeed, to earn one’s death by confronting with passion the conundrum of life.” – James Baldwin.

I Am Not our Negro is currently playing in selected theatres . It is also available on ITunes and Amazon .

Sammus – Time Crisis – Song

Sammus is my current aural obsession. Her track, Time Crisis, immediately calls to mind one of my favorite pieces from Caitlin Doughty, What the Dead Can Teach Us About Aging and Beauty, in which she challenges our death denying ideas of physical aesthetics and the value we place on youth.

I’m complaining we live in a system / in which aging’s an act of resistance / I am a mortal, yeah I ain’t the Highlander / I’ll be a corpse one day under a pile of dirt

Watch Time Crisis on YouTube or purchase on iTunes.

Contributors:

Gabby DaRienzo is a Toronto-based independent video game developer and artist, who is currently developing death-positive funeral home simulation game A Mortician’s Tale with her studio Laundry Bear Games. When Gabby isn’t making games, she hosts and produces the Play Dead Podcast which talks with game developers about how death is used and approached in their games. You can follow Gabby on Twitter, where she tweets about death, videogames, and art.

Krista Amira Calvo is a bioarchaeologist living in a tiny studio apartment in the Upper East Side with her partner, a necromancer. She excavates and studies human remains, sometimes in Transylvania, and studies the anthropology of death and end of life care in third world countries. She loves ramen, her two cats, and television shows about food. She is currently doing research on feminism in bioarchaeology while simultaneously feeding her partner her subpar attempts at authentic ramen. She is very death positive. Follow Krista on Instagram.

Myeashea Alexander is a biological anthropologist and science communicator from Brooklyn, NY. Currently, she is researching early African- American communities, burials, and skeletal pathologies. Additionally, Myeashea manages her blog, The Rockstar Anthropologist, and operates a mobile bone lab as part of her public outreach project that provides hands on learning opportunities for classrooms and community centers to learn about forensic anthropology, archaeology and science. You can follow Myeashea on Twitter and Instagram.

Sarah Chavez is the executive director of The Order of the Good Death and co-founder of the feminist death site, Death & the Maiden. With a costumer father and a celebrity publicist mother, Sarah spent her childhood on the sound stages of Hollywood, immersed in the pop culture dream factory of Los Angeles. She currently resides on a farm in California, where she does things for her Italian Greyhound, and cooks funeral and death ritual foods. You can follow Sarah on Twitter and Instagram.

Pop Goes the Reaper! original artwork by Momalish Follow them on Instagram.

May 6, 2017

La Pascualita: MANNEQUIN OR CORPSE BRIDE?

May 2, 2017

Is There a Doctor Onboard? On Facing Death at 40,000 Feet

The first time the flight attendant came over the intercom, interrupting my viewing of X-Men: First Class, I glanced around the cabin hoping I’d see an arm reaching up to hit the flight attendant call button. Even with my earbuds in, I could sense a ripple go through the economy cabin.

The second time the flight attendant’s voice froze Magneto mid-realization of his extraordinary potential thus planting the seeds for the war against Charles Xavier’s dreams of mutant equality (I fly a lot, I’ve fallen asleep to this movie, a lot), I think I may have softly said, “Uh-oh…”

“Attention passengers, again, if there are any doctors onboard, or any people with medical training traveling with us today, please press the flight attendant call button.”

In the semi-dark cabin, lit only by other people watching The Big Bang Theory or X-Men, people began to rumble and shift over the realization that something was really wrong with one of our fellow travelers.

Attention seemed to be focused toward the front part of my section of economy. Heads turned forward and to the right, flight attendants kept rushing by me.

I leaned into the aisle and craned my neck to see if I could catch a glimpse of where exactly the emergency was occurring. To my surprise it was only about five rows ahead of me. A flight attendant holding what looked like a red emergency medical case stood in the aisle holding a tiny flashlight trained on someone hidden in the row of seats. A man and a woman in plain clothes stood with her, taking turns leaning in and doing something.

The cabin started to feel very cramped. People were fidgeting more, there was a murmur amongst my fellow travelers. Heads turned between video screen and the direction of the emergency, trying to remain covert. Others “went to the bathroom”, slowing to glance at the situation, like they were passing a wreck on the 101. After a while I saw the flight attendant tell a passenger to use the bathroom at the other end of the cabin.

The woman across the aisle from me and one row forward was practically wringing her hands, and looked imploringly at every passing flight attendant.

It got real when the flight attendants opened a few of the window shades in the middle of the “night”, effectively lighting up the whole cabin.

With the lights on, everything seemed to ramp up.

One of the flight attendants came rushing past me, headed to the galley directly behind me. She spoke in hushed tones with her coworkers. Words like “chest compressions”, “IF they make it…”, and “seizure” floated over to me above the general hum of the plane. One of them said something about a “protocol” and a “code”.

At one point, a flight attendant RAN down he aisle to the critical passenger. Seeing this, my heart jumped into my throat for a moment; I reflexively held my breath for a moment.

When I’d worked as a stage manager for a giant outdoor theater festival, our policy was “running means panic” – you only ran when there was an emergency. Though that was over a decade ago, seeing professionals run still sets off alarms in me.

As that attendant ran by, she swept the polite avoidance of the situation away with her: someone might die on this flight.

The screws of tension tightened.

The woman ahead of me with the wringing hands appeared as if she might vomit. She looked ahead at the gathered professionals, looked around the cabin, up at the ceiling, and tapped her feet. I sincerely hoped that she wouldn’t be the next person needing medical assistance.

A man directly across the aisle sighed loudly in frustration. Anger radiated off of him. Every time a flight attendant passed him, he stared hard at them, obviously hoping they would see his quiet fury and feel…shame? The need to attend to his inconvenience? Every few minutes he’d huff and resettle in his seat, throwing nasty looks in the direction of the medical emergency.

When a portable defibrillator was carried up the aisle, the woman in the middle seat next to me – who had previously been whispering excitedly at her companion, a boyfriend-type who seemed much more concerned with a Chinese cop movie than with someone dying a few rows ahead – couldn’t take it anymore, and used my shoulder to prop herself up and over the back of the seat in front her, so she could get a better view.

A man on the opposite side of the cabin was standing up the aisle, arms crossed, casually watching the cabin crew and who I assumed were medical professionals “work on” the patient. His expression was stoic, I’m not sure he blinked. A flight attendant gestured for him to sit back down at one point, and he did – for a moment. As soon as the flight attendant had gone back to the galley, he was back up again, position assumed.

Looking at the wide middle section of the cabin, heads kept popping up like Whack-a-Moles to catch a glimpse of what was happening. Some looked concerned, some looked even looked amused. Most looked afraid.

Near the bulkhead, ahead of where the emergency was being attended to,/people would go to or come out of the bathroom and almost walk into a wall as they stared, stoney-faced or wide-eyed at the situation. One woman gasped and put her hand to her mouth. What did she see?

The people in front of me were speaking to each other in Cantonese. I caught, “This is so bad…is it a man or a woman?…will they tell us anything?”

The man across the aisle growled and rolled his eyes.

I feared the woman next to me might pull something while trying to catch death in the act.

The hand-wringing woman looked like she might have started to cry.

Every time a flight attendant whooshed by me, I wondered if they would ever breath again.

I watched a cabin full of people struggle through the fear, panic, anger, frustration, fascination, and/or horror that death might very soon be among them. Sharing their processed air. Decaying in their mist. (Not really, but I call dibs on that title for my centenarian memoir.)

In a flying metal tube, like it or not, we all had to think about death. It was like “How We Handle Death” bingo.

There were the deniers, the avoiders, the thrill seekers, the utterly terrified, the begrudging handlers (my heart went out to those flight attendants – for the record they were poised and so professional), the unruffled (one fellow practically across the aisle from the goings-on glanced over maybe once and then dozed off reading his paperback), and the rosary wielding pray-ers, among others. BINGO!

While my seat mate couldn’t help but try and watch the medical intervention, I couldn’t help but watch people be forced to consider death, perhaps for the first time, on an AIRPLANE OF ALL PLACES. If death was something I made a point to push out of my thoughts, an airplane is NOT where I’d want to be confronted with it. Woe be to the person who has to contend with a fear of flying and a fear of death all at once.

By now you may be pondering two things:

1) What happens when a person dies on an airplane?

2) What became of the person on that DEATH FLIGHT?

To answer your first question, nobody technically dies on an airplane. OK, yes, obviously in-flight death can happen, does happen, and has happened, but unless there’s a doctor onboard, the person cannot be pronounced officially dead until a doctor on the ground does so.

In most cases, when a person falls gravely ill on a flight, cabin crew and/or the captain will try to communicate with physicians on the ground and decide whether or not to stay in the air. Very often, like on my flight, the crew will enlist the help of any medical professionals on the plane. Flight attendants are trained in some first-aid and emergency procedures.

But if a person does “unofficially” die on an airplane, airlines have few “hard and fast” rules for handling the dead. The important thing is to not upset the living, and if possible, not alert them to the fact that death is flying the friendly skies with them (this is NOT a jab at United…I’m sure they have lovely death practices).

Singapore Airlines is one of the few airlines with in-place death “procedures”. Their protocols simply codify what most airlines do in the event of this sort of situation.

Singapore Airlines told Quartz in August of 2016, “The deceased will be moved to an empty row of seats and covered in a dignified manner. If no seats are available, the body will be left in the deceased’s existing seat. Customers seated next to the deceased will be moved to other available seats wherever this is possible.”

Customers will be moved if possible. Think of this the next time you’re on a long-haul, international flight (the likes of which Singapore Airlines is known for), that’s oversold. You better hope that mouth-breather next to you keeps breathing.

Some airlines have placed the deceased on the floor of the galley covered with a blanket, or even upgraded them to First Class if there’s more room (score!). Singapore Airlines’ now out-of-service Airbus A340 had what they called a “corpse cabinet”. In the event of an in-air death, the corpse would have been strapped into this compartment, away from the other passengers. The A340 was retired without any of the corpse cabinets ever having been put to use.

What about the bathroom you might ask? Nope. The corpse can’t be properly secured, and if they fall down during turbulence or landing, they might make opening an inward-folding door impossible. You’d then have to disassemble part of the airplane, and you know that Barbara from that snarky Phoenix-based flight crew would never let you live it down.

Barbara.

So the next time you see someone in an empty row, “sleeping” with a blanket covering their head, you might want to think twice about grabbing the aisle seat next to them. Or do. Leg room is power.

And what became of the person on my flight that forced an airplane of people to FACE THEIR MORTALITY?

They survived the flight and landed in Los Angeles. Upon landing, we were told by a ragged but FIRM flight attendant over the intercom to “STAY SEATED” while emergency medical technicians removed the person from the plane. This didn’t stop a few people from standing in the aisle IN THE BACK OF THE PLANE, impatiently waiting to exit. I’ve never understood this behavior.

I don’t remember much about the removal of the sick passenger. It was a blur of EMT’s and flight attendants. I chose not to rubberneck. My neck was tired.

My seat mate did not share my choice. I thought she might pop a vein trying to periscope her neck just a little longer over the seat in front of her.

The dude across the aisle from me blessed us all with one more HUFF.

The poor hand-wringer closed her eyes and twitched.

Make no mistake, the flight was one of the most stressful I’ve been on and the tension was palpable. I can’t imagine the anxiety and fear that a person might experience facing their own death on an airplane.

One minute you’re on vacation, going home, or going to see family, and the next thing you know you’re fighting for your life in a cramped coach seat having to rely on people who are admirably doing their best, but might simply be out of their depth.

Not to mention that your illness and potential death is the furthest thing from private. Not only do people have almost no choice but to be a party to your situation, but you have almost no choice to but include them. If you die on an airplane, it is a communal event whether anybody wants it or not.

As I deplaned and got a last look at the faces of the people who’d shared this experience with me, I wondered how they’d remember this flight. As the flight that swore them off flying? As an inconvenience? As an eye-opener?

Would some people just choose to forget it?

Honestly, I hope nobody forgets that flight. I’d like to think if even a few of those people complain, cry, or crow about how death almost made an appearance on their flight, the conversation is started. People who’ve never talked about death before will have a personal, palpable reason to do so.

For many of us, the acceptance of death starts with a life-changing event, a unique story. Perhaps, for a couple my fellow economy travelers tucked in the back rows of that non-stop Hong Kong to Los Angeles flight, this might be theirs.

Louise Hung is an American writer living in Japan. You may remember her from xoJane’s Creepy Corner, Global Comment, or from one of her many articles on death, folklore, or cats floating around the Internet. Follow her on Twitter.

April 28, 2017

WOULD YOUR CAT OR DOG EAT YOUR CORPSE?

April 26, 2017

ASK A MORTICIAN- Painting with Human Remains!

Faces Of Death: Elizabeth Harper

Tell us about your work, Elizabeth.

I photograph and write about the unusual (and often macabre) things I find in Catholic churches—incorrupt corpses, holy relics (which are often the preserved body parts of saints), memento-mori tombs, exotic taxidermy, human bone art… Basically the kind of things people might see while touring an old church but also might not fully understand. I want to make the meanings of these things more accessible. But I also want to talk about why they’re worth preserving and think about how they’re still relevant.

Sant’Agostino, memorial to Cardinal Giuseppe Ranato Imperiali, by Paolo Posi (design) and Pietro Bracci (statuary), 1741. Photograph by Elizabeth Harper.

What are you working on this year?

As I write this I’m on my way to Zamora, Spain for their famous Holy Week. It’s basically a whole week of ritualized funeral processions before Easter. I also have an essay coming out in the Paris Review in a week or two. It’s about a naked mummy named Uncle Vincent. A bunch of people in a small town in Italy decided he was a saint against the Vatican’s wishes and put him on display. Then this summer I’ll be speaking at the Death & the Maiden conference at the University of Winchester, talking about what holy relics have to do with the Romantic obsession with beautiful dead women. Finally in the October, I have an essay coming out in Death: A Graveside Companion, published by Thames and Hudson with fellow Order member Joanna Ebenstien. It’ll be a great Halloween read.

What does death positivity mean to you?

For me, it means uncovering and reintroducing ways people in the past made death an undeniable, meaningful part of life—think of all those classic crypt inscriptions like “Today me, tomorrow you”. But it also means investigating how a lot of our ideas about death and the body were shaped by Catholicism in less positive ways—it’s how a lot of paternalistic and colonial attitudes spread. But hopefully I hook people with the weird, macabre stuff and leave them thinking about the bigger questions—What do I think happens to the dead and where did those ideas come from? How are the living supposed go on? How has our modern, secular idea of death been shaped by these older ideas? And most importantly, how do we grapple with all of that today—what can we learn from the past and what can we work to correct?

St. Vittoria, photograph by Elizabeth Harper.

What other death-related job that you don’t have, would you want?

I probably think about joining the “Company of Death” in Rome too much… monthly at least. They’re kind of a grief-related charity today but what I daydream about is joining the group of nuns who oversee the company’s baroque crypt of bones under the church of Our Lady of Eulogies and Death. I could give tours of their crypt and print up brochures. If they need me to wear a long black skirt, that’s also not a problem—it’s already part of my look. But renouncing the world… well… I’d make a bad nun on that front so I probably won’t get my dream job any time soon.

When you die, what do you want done with your corpse?

This is weird even by Order of the Good Death standards and I think impossible, but I’m being serious. I would like to be a chandelier. I want my bones dried out, disassembled, made into a hanging lighting fixture and wired up. You can see other people-chandeliers in crypts all over Europe. It really isn’t done anymore but I think I have good reasons. Since being the aforementioned crypt-keeper isn’t really in the cards (but call me if something opens up) my real job is in lighting design. So becoming a lighting fixture makes perfect sense. And I love seeing bone chandeliers that used to hold candles now wired up with flickering LED light bulbs in some of these crypts. What an amazing afterlife. I could illuminate, evolve with new technology, become art… what could be better? And at the heart of it, few things have given me more pleasure and meaning in life than contemplating my own life in these crypts. So I’d like to provide the same as a service to the living… and light their way.

Bone chandelier at Sedlec Ossuary. A glimpse at Elizabeth’s postmortem future.

Can’t get enough Elizabeth? (We can’t either), check out her blog, All the Saints You Should Know featuring her photography and equally stunning writing. Not to be missed are Elizabeth’s pieces, Appetite For Destruction from Please Hold Magazine and Our Adored Cadavers, in Hazlit.

Elizabeth has been featured in Vice , Los Angeles Magazine and Swide: The Dolce & Gabanna Luxury Magazine. You might also remember her from her two Ask a Mortician appearances – How to Tell if Your Saint is Incorrupt and We’re Here to Ruin Santa.

You can find Elizabeth on Facebook and Twitter .

April 21, 2017

MAKING A DEATH DOCUMENTARY!

April 18, 2017

My First Death

My cousin and I couldn’t stop giggling.

We sat at a big round table with a Lazy Susan in the middle, synonymous with any big, banquet-style Chinese restaurant you might imagine stateside or elsewhere. The food we’d feasted on was long gone – a big, red crispy skinned chicken, a pile of fried race, fried turnip cakes, congee, maybe some egg rolls for the kids – and all that was left were the grease stains and bits of rice that are cemented as in my memory as part of a family meal, almost as much as the food is. We came, we ate, we conquered, now gaze upon the carnage.

Tai Cheong Egg Tarts, by chee.hong on flickr https://www.flickr.com/photos/chleong...

But instead of the grown-ups arguing over which deserts to indulge in (I always hoped for mango pudding) while picking their teeth with toothpicks behind cupped hands, the table was oddly subdued. The jokes that normally flew back and forth between my dad and my uncle, punctuated with my mom’s melodious, high-pitched laugh were hesitant and inconsistent. My mom looked downright cranky.

Tomorrow was my grandma’s funeral, and my younger cousin and I (she was 10, I was 12) didn’t know how we were supposed to feel, let alone behave.

My aunt Nora* couldn’t stop crying. She’d pause momentarily, her voice returning to it’s low, soothing British tone to talk about a trivial thing like where to get the best beef jerky (there are shops devoted to it in Hong Kong) or how much she liked her new jumper. But then something would set her off again, and her voice would break, her head would drop, and she’d sob. Through her sobs, I could hear her saying things like “mum” and “I’m so sorry.”

Unfortunately, my aunt had no fellow “weepers” amongst her siblings. Her older brother, my Uncle Carl, seemed downright jolly. A surgeon, and already rather casual about life, death, and the body’s inner workings – one of my favorite memories from childhood is gathering around the TV to watch the video of his knee surgery – Uncle Carl was just delighted to have the whole clan all together in Hong Kong.

“Mom left us a long time ago,” he said matter-of-factly. “She doesn’t have to be stuck in her old, tired body anymore. What a relief!” He shed no tears, he only cracked jokes. As my grandma’s favorite child, I wondered if she would approve of his demeanor. Probably, she was rarely precious about matters of mortality.

My mom, the oldest, and her middle sister, my Aunt Jane, were rather stoic. No, actually Jane seemed to be perpetually fending off a dazzling fit of eye-rolling over all the “theatrics” the clan was enacting.

“If I had it my way, I’d just cremate mom, scatter her ashes, and go eat lunch. Mom is not suffering anymore –“ then to her younger weeping sister, “– you wish she was still suffering?”

Aunt Jane didn’t meant to be so harsh (OK, maybe she did), but after living with, and caring for my grandma for years now, she was unabashedly relieved. Along with Aunt Nora, she’d watched my grandma go from a strong, opinionated woman to a timid, smiling stranger, cruelly stripped of her intellect by dementia.

Grandma’s death was relief for Jane and peace for grandma. “You don’t know, you don’t know what it’s like to see someone know they have forgotten everything, but they try and try and they cannot remember. It’s torture. I’d rather kill myself.”

Of all my grandma’s children, Jane resembled her the most in appearance and manner. I suspect it was troubling for Aunt Nora to hear such things, especially in a voice that so closely echoed her mother’s.

Jane wanted to move on, not dwell on her mother’s death; Nora just couldn’t. Not yet.

My mom found herself having to strike the balance for the family between her sister’s tears and her brother’s flippant remarks. This irked her more than her mother’s death.

While my mom harbored a lot of unspoken sadness and regret over the loss of her mother, her actual death did not upset her. Her absence, the things she didn’t get to say to her, the fact that she suffered – but not her death. Mom was almost as clinical as Uncle Carl when it came to death and dying.

But, because she’d always been charged by her mother as being the “responsible” one, the “strong” one, Mom felt the need to soften her unsentimental attitude towards death for her grieving sister’s sake.

I admit seeing my mom awkwardly reaching a hand out to pat her tear-soaked sister, her face contorted into a look that said, “THIS IS WHAT SYMPATHY LOOKS LIKE ON HUMAN FACES, RIGHT?”, freaked me out. I knew she wanted to soothe her sister, but the family’s subtext of, “But really, it’s fine,” hung heavily in the air.

“Oh, Nora. I know. It’s hard. I know you wish we could have done better for mother. But she doesn’t have to worry about all that now. I’m happy for her.”

I’m happy for her.

Even weird, immature, 12-year-old Louise knew that was the WRONG thing to say to crying Aunt Nora.

But I didn’t know what to think. Neither did my cousin Dana. This was our first exposure to death that wasn’t a turtle or a goldfish, and we were getting mixed signals. Hence the giggling.

We couldn’t stop.

It wasn’t the death that had us uncomfortable. That’s not how my family rolls. It was seeing the adults so uncomfortable that made us uncomfortable.

None of it was funny, but all of it was strange. I’d never seen an adult cry so much in real life. I’d never seen my mom so ill at ease.

I’m not sure any of the family knew quite what to do with each other. Everyone seemed to have their own idea of how to handle Grandma’s death; how to do it right. But somehow sitting around a table with Chinese food debris scattered around, while my uncle regaled us with the detailed story of the horrible food poisoning case he’d treated on a plane returning from Mexico, somehow seemed the most right. At least to me.

But then Aunt Nora would cry and I would start to giggle, setting off Dana.

The family was a mess; just not the kind of mess you’d expect before a funeral.

The next day I got dressed in a blue and white plaid skort-and-vest outfit for the day’s activities. You read that right, skort (skirt + shorts = skort). I looked like a Delia’s catalogue Catholic school girl.

I think my cousin wore a hand-me-down outfit of mine: a skirt and shirt set in – wait for it – neon orange tie-dye.

My mom purposely had everyone wear “not black” to my grandma’s Buddhist Chinese funeral. Everyone happily complied…except for Nora.

Poor Nora. Over time I’ve come to truly love my aunt – she’s actually as steady as they come, with a disarming capacity for sympathy. However, during grandma’s funeral I actively avoided her. She frightened me more than my grandmother’s corpse.

We took a few taxis to the hall where my grandma’s body lay. I don’t remember the building itself, only that it was very cold, that we took a gray elevator to an upper floor, and that it opened into a gray tiled hallway. We walked a little way down the gray hallway before turning into a huge room that exploded with color.

The far wall of the room shone with twinkle lights and shiny gold wallpaper accented with bright green, blue, and pink Chinese designs. On top of the wallpaper background were gold Chinese characters printed on green (velvet?) squares – each probably about two feet by two feet in size.There were candles and incense and framed octagonal mirrors at an altar. A white banner, I suspect with my grandma’s Chinese name written on it, was suspended over one side of the alter. The whole set-up was rather blinding after the gray of the hallway.

Near the altar sat my grandma’s coffin. It was tan, I’m not even sure it was wood. It sat atop a heavy table of some sort. The table was draped in white cloth. Grandma lay peacefully in the coffin.

I know it’s cliché to say, but she really did look like she was sleeping. I was afraid that her corpse would scare me, but it didn’t. The atmosphere felt celebratory.

I don’t really remember a service, exactly. Plain brown plastic chairs lined two sides of the room – like at a middle school dance in the cafeteria – and I remember my mom telling everyone to sit down at one point. We all lined one wall of the room, and two monks came in and recited some prayers or chants over Grandma, and at the altar. It sounded like singing to me.

Here and there I heard Nora softly cry. I noticed my mom reaching out for her and Nora leaned into her. This time, I didn’t giggle.

I clearly remember one of the monks smiling right at me as he walked past on the way to the altar. That’s all I really remember about the monks. I remember liking their company.

After the monks finished, the family stood up and we milled around the room. Dana and I inspected the altar, finding oranges and a picture of grandma and grandpa in their youth, as well as a picture of grandma’s parents.

Talk filled the room, even the occasional laugh. The family spoke in clusters around grandma; nobody seemed at all concerned that a corpse was in the middle of us all. At one point, I made my way to her side and stood staring at her, wondering what was so scary about a corpse.

***

Unlike a lot of my friends at home in the US, death had never been a taboo topic in my house. True to the picture I’ve painted so far, my mom believes that the body is temporary, that the spirit is what matters, and that it is a fool’s errand to fear death.

Death, questions of what happens after we die, how the dead are cared for were favorite topics. Spending a good part of my childhood in Dallas, Texas, we were the loud Chinese family at the catfish restaurant that you’d overhear barking, “No! Don’t you dare embalm me when I die!”

I have clear memories of my mom making me rewrite homework assignments in grade school because I’d chosen to write about, “The Time My Dead Great-Grandma Stayed Home For Three Days” (a story about sitting vigil with the dead in Hong Kong). Mom probably knew she was raising a little Wednesday Addams, but she wasn’t sure if Mrs. Ward and my fifth grade class needed to know too. Not yet.

So growing up I learned how to gauge how much I could say to people. Teachers, parents of friends, volleyball coaches – I stuck to the script of being disinterested in “gross” things like death and corpses. Like, ew. I let myself be shielded from even the thought of death and deathly things.

Occasionally I’d meet a young friend who I thought liked cemeteries, ghost stories, and funeral stuff as much as I did, but they always pulled up short when I’d ask them if they wanted to be buried or cremated.

“You asked Cary that?” my mom once said. “Americans don’t like talking about that stuff, they’ll think you’re weird.” She followed up with, “You are a little weird.”

But so is she, and the way she talked about death back then, as just a mysterious eventuality, made sense to me. Death still scared me as a child, as it does today, but the fear is not paralyzing. I’m much more afraid of home invasion, poltergeists, and the very real scenario that all my teeth have cavities and I’m going to need full dentures by the time I’m 40.

***

“You know she’s frozen.”

Uncle Carl had appeared next to me at grandma’s side.

“She’s not embalmed. She’s just frozen.”

And before I could respond he reached down and knocked on Grandma’s forehead. Despite my juvenile “okayness” with death stuff, my mouth fell open.

Partly because I wasn’t sure if it was disrespectful and I should be outraged, and partly because of the sound her frozen head made. I don’t know why, but her head sounded surprisingly hard. Like if you had a giant, human head sized frozen grape. And you rapped on it.

I reached down and touched grandma’s shoulder. She was so cold and felt so totally foreign. For the first time I understood what my mom meant when she said, “Bodies are just shells. When you die they’re empty. Why be scared?”

I don’t know if I ever told my mom that I touched grandma’s dead shoulder. In navigating between how my family regarded death and how everyone else back home seemed to regard death, it felt like a stolen moment that I should keep to myself.

Soon we were all gathered up and got into more taxis to go watch Grandma be cremated.

I’m not quite sure where we went, but it was out in the more rural part of Hong Kong, outside the bustling city. We all gathered before a big, white, outdoor furnace and my uncle and some men put grandma and her coffin (oh! it was cardboard!) onto a conveyor belt. I think a switch was hit, and the doors to the furnace roared open as the conveyor belt moved Grandma’s body closer and closer to its fiery end.

She entered the fire and the doors slammed shut. We then stood around a bit, not knowing what to do. Finally someone who worked at the crematory told us that it would be a while and that maybe we should come back the next day to get her ashes.

And that was that.

One more time we loaded into some taxis and caravanned to a restaurant on Hong Kong island. There, we all made it a point to eat noodles for long life and sweets to shed any lingering sadness. “It’s important to be happy after you’re so close to the dead, so no sorrowful or angry spirits will follow you home,” my mom says.

And I was happy. Not exactly jumping for joy – no matter how much of a stranger my grandma had been to me, the realization that my mom’s mom had left her, that the woman who hugged me so tight as a little girl and sent me trinkets in the mail with red packets that said “I love you!” in Chinese on them was gone, made me mourn for the relationship I would never have with her.

But I was happy that I had gotten to be there. It was like being in the inner sanctum of my family. My grandma’s death had been the sad part, her funeral was the celebratory part. How she was to be remembered was just being born.

Since my grandma’s funeral, all the funerals I’ve attended have been in the US. They are all much more somber affairs; there are always many more “Noras”.

Whenever I see young children at these funerals, or even “tweens” like I was at my grandma’s, I wonder how they are taking it all in. Is a solemn funeral, draped in black, with a procession to view a corpse in a fancy casket, a daunting experience for them? Do they feel afraid?

Do they have any relationship with death? Is this their first time seeing death up close?

When I wonder about these young people, I feel grateful for my first experience with death. While sadness pricked the edges of my family’s experience, and Aunt Nora’s tears kept reminding us that “Mum is gone”, I was never afraid. Once I got past the nervous giggling, I’d say Grandma’s funeral and cremation were peaceful, even soothing.

My first experience with death was fortunate in many ways. My grandma’s death was not unexpected, premature, or horribly painful. It was not a shock to my family, but a relief. As death goes, it was one of the gentlest introductions.

Coupled with the talks my mom and I had about the dead, my grandma’s funeral and cremation gave me positive memories on which to form my opinions of death and death care.

My grandma had wanted to be a surgeon in life. She never got that chance because she was a woman born in a time and place where women rarely did such things. But in her youth she had frequented hospitals, snuck into morgues, trying to learn as much as she could from the dead. It was her passion.

I suppose then, that it’s appropriate that her corpse was the one that taught me my first real lesson about death. I think she would have loved this. Her death became a precious part of my life.

*All names were changed to protect the identity of my family.

Louise Hung is an American writer living in Japan. You may remember her from xoJane’s Creepy Corner, Global Comment, or from one of her many articles on death, folklore, or cats floating around the Internet. Follow her on Twitter.

April 14, 2017

REACTING TO COMMENTS ON MY TED TALK

April 10, 2017

TOMB SWEEPING DAY!!!

Caitlin Doughty's Blog

- Caitlin Doughty's profile

- 8409 followers