Caitlin Doughty's Blog, page 24

January 18, 2018

Death Positivity in the Face of Grief

I spent most of my 20’s studying death – through mythology, ritual, art. I was intent on making people think about the things they shied away from. Not because it was morbid, but because it was fascinating: all these things that seem unrelated link up with just a little bit of digging. You pull one dark string and the whole world snaps into place.

Being willing to talk about lots of things that made ordinary people uncomfortable made me not the most fun at dinner parties back then, but it gave me a really beautiful life.

I met my partner when I was 34. He was different. I was different. Instead of looking at each other with that half-cautious raised eyebrow, slightly uncomfortable thing people give you when you’re just being your normal strange self, we relaxed around each other. We spoke the same language. Our early courtship days were full of discussions on religion, fears of death, the cultural intersections of personal loss and addiction. We talked about death a lot. The first time I saw him naked, I told him he had a great body. He said, without missing a beat, “thanks. It’s a rental.”

Eight years ago, I watched him die. He drowned on a beautiful, ordinary, fine summer day.

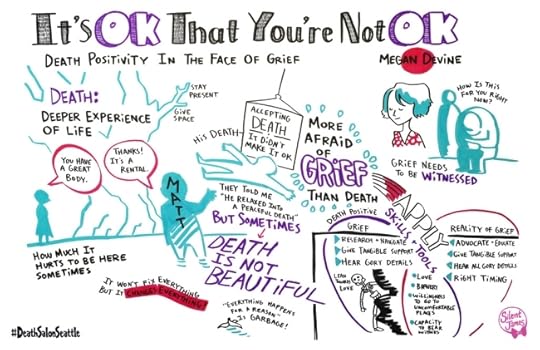

Live illustration of Megan’s talk at Death Salon: Seattle by Silent James.

My understanding of death as a natural process did not help me. My familiarity with death rituals and funerary art and the darker, harder aspects of life did not make his death – or my grief – any easier. Accepting that death happens can’t make death okay. Not Matt’s death, and not deaths that many in this world see.

I don’t think it’s intentional, but I think a lot of what we have in mind when we think of death positivity is death that happens at the end of a normal, natural, expected western lifespan. In those kinds of deaths, you get to be sad, yes. But it makes more sense, in addition to that sadness, to lean on our ideas about the cycles of life, of the beauty in a life lived well. Death positivity feels really congruent in the face of those kinds of deaths.

But that’s not the only way we die.

Sometimes death is not beautiful. Sometimes death is not normal. Sometimes death is wrong.

There’s a weird, clanging disconnect when we try to apply what we know as death positive people into the gaping open wound of death itself, especially the “out of order” kinds. Accidents and natural disasters can’t be treated as a “natural process.” Hate crimes, gender-based violence, deaths hastened by lack of access to health care, death created by acts of war or targeted genocide – we can’t claim those deaths as beautiful. We can’t use our standard language here. Talking about these kinds of death – and the grief that comes with them – is one of the last real taboos.

What I hear from people grieving losses from these kinds of death is that being friendly with death – even being deeply interested in it as a cultural exploration – feels wholly irrelevant to their grief. A mother whose 14 year old son was killed by a drunk driver told me recently that the death positive movement felt “too hip to be of use.” That the art, the cafes, the memes about day of the dead, and roman crypts, and bat tattoos felt flippant in the face of what they were living.

I hate that. And, I get it. Without meaning to, we can alienate or injure people going through some of the hardest times of their lives.

There’s so much beauty, so much potential inside what we know as death positive people, but there is a chasm there, between the ways we talk about death in the abstract, and the ways we live inside actual grief.

We’ve got to start talking about grief in the face of deaths that are not beautiful.

The ways we come to grief due to violent or accidental deaths is really no different than the ways we need to come to all grief: with kindness, compassion, and acknowledgment for how hard it is to be here sometimes, how hard it is to love, and to lose those we love. In grief paired with violence in any form, it’s important to acknowledge the injustice of the death while not losing sight of the intimate loss itself: too often, the intimate loss is obscured by communal outrage. At the same time, we have to acknowledge the nature of the death, knowing that injustice is deeply stitched into grief itself.

Memorial wall for Black Lives Matter by David McNew

It’s holding your primary focus on the intimate loss, while keeping your eye on the wider cultural reality, that will make you invaluable if and when non-beautiful death erupts in your life.

What we’re really doing, in both the death positive movement and its sister, the grief movement, is turning towards what feels scary and painful. We’re building skills, and gathering knowledge – not to avoid grief, but to withstand it. To able to companion each other, no matter what comes. Accidental death, baby death, atypical death, death due to violence, hate, or exclusion – they all belong in the death positive movement, but there’s one special rule for addressing them:

The Code Switch. There’s a difference between talking about death positivity, and acting from your knowledge of death. We can’t have a death positive movement without making room for uncomfortable deaths, but not all of our tenets apply. To truly support a grieving person, you need to know which aspect of death positivity matches the situation. Recognize that ideas about how death is treated in Western culture belong in certain spaces, while your knowledgeable presence – as a resource, as a support, as an ally – belongs in others.

So what does your interest and knowledge allow you to do in the face of death and grief, especially the deeply uncomfortable kinds?

Be the crows on the battlefield, turning towards what scares others off. Because people are often afraid to upset people or freak them out, they don’t share the actual physical details of the death, especially if it was violent or upsetting. But those details might need to be told.

Action: Be known as the person who can withstand the details, ask intelligent and informed questions to help the grieving person tell the story. Your knowledge lets you listen. Let them tell the truth about what happened. Don’t pretty it up. Don’t turn away. Be willing to hear it again and again.

Know the options. There’s often a lot of turmoil in the first weeks after an accidental or violent death; it’s heightened by shock, and sometimes by media coverage. When Matt drowned, I needed my death-skilled friends to find out what my legal options were for the care of his body. Their research helped me step out of the extended family drama and tend to his body in ways that felt congruent with who I knew Matt to be.

Action: Know what the legalities are around death and burial in your city and state. Your knowledge lets you navigate these for your friend or family member. That’s a great use of your skills.

Take on unbearable tasks. There were four of us together at the morgue when we signed the papers to have Matt’s body cremated: Matt’s son, one of Matt’s friends, me, and one of my friends. Matt’s son turned 18 the day after his dad died, so he was asked to identify Matt’s body. He declined. I declined. Both of our friends offered to ID Matt’s body for us. Over eight years later, that gift still means more than worlds to me.

Action: You can be the person who does what your friend cannot. Offer to accompany your friend to the morgue. Identify their person’s body, or do other things they cannot bear to do. Your knowledge allows you to withstand that emotional hit. That kind of support is invaluable.

The death positive community is better trained for this kind of work – already – than many will ever be. We make death friendly and accessible so people can talk about death, but we can go a few steps further and find words – and ways – to talk about the reality of grief. We can open conversations about what it means to live in a world of accidents and acts of violence, where death is not always beautiful or normal. And we can stand by each other, rooted in what we know of death and life, creating a world where every part of being human is considered sacred, and worthy of love. That’s where the beauty is.

Megan Devine is the author of It’s Ok That You’re Not Ok: Meeting Grief and Loss in a Culture That Doesn’t Understand. She’s a licensed clinical counselor, writer, widow, and sought after speaker. Her Writing Your Grief courses have connected grieving people all around the world, helping them speak the truth about their pain. You can find more of her writing and sign up for her weekly letter, at www.refugeingrief.com.

January 13, 2018

Flying, Firey Carts and Corpse Stealing Cats

Like the man-eating nekomata, the monsters of the Kamakura period (1185–1333) were on the scary side. This is partly due to an apocalyptic belief in mappō, a Buddhism term meaning “the latter of the days of law.” Like some Christians today, Kamakura-period Buddhists believed they were living in End Times. The world would soon be over.

People believed that the cycle of reincarnation had reached its end, and there would be no more chances, no more lifetimes to redeem lost souls. Anyone still alive was stuck between damnation and redemption. It was your last opportunity to plead to the Amida Buddha for mercy, and hope he would grant you a spot in the heavenly garden known as the Jōdo Pure Lands. If not…the oni were waiting to flay your skin from your bones for all eternity.

This fear lead to a form of art called jigoku-zōshi, meaning “hell scrolls.” These depicted the painful suffering awaiting those who didn’t hurry up and get saved. Like medieval Christian art depicting Satan and damnation, hell scrolls were designed to terrify an illiterate population into following the righteous path of the Buddha.

Most of these paintings depicted oni tearing people apart and feasting on their body parts. Sometimes oni carried these poor bodies in flaming carts. The belief eventually developed that oni crawled the Earth looking for sinners and piled them into flaming carts to drag before the dread judge of hell, Emma-O.

As with much Japanese folklore, the image of the flaming cart went dormant with the end of the Kamakura period. The people of the time were right about one thing—their world did end in a way. About a century following the end of the Kamakura period, the political structure of Japan collapsed. Numerous samurai lords called daimyo each decided they should be the sole ruler of the country. This led to a massive period of civil war known as the Sengoku Jidai, or the Warring States Period (1467–1603). Most of Japan was too busy killing and dying to fret about yōkai. The monsters disappeared until Tokugawa Ieyasu came out as the winner of the civil wars and began the 260 peaceful years of the Edo period.

The flaming cart, now called kasha or hi no kuruma, was reawakened during the Edo period. Removed from its oni companions, the flaming cart began to appear descending from the sky, accompanied by thunder and great winds. Superstition said that when thunder was heard during a funeral procession, it meant the kasha was coming.

What exactly this flaming cart was coming for, and who exactly was riding it, wasn’t clear at first. In the 1687 book Kii-zodanshu (奇異雑談集; A collection of the idle chat of mysterious things) there is a story called “The thing that came from the storm clouds to steal a corpse in the manor house near the rice fields of Echigo.” During a funeral procession, there was a loud clap of thunder and a beast riding a flaming cart came down from the sky to snatch the dead body. An illustrator depicted the kasha as being ridden by Raijin, the Shinto deity of thunder and lightning. This association made sense if you think about the carts’ association with thunder.

All of the appearances of this kasha were heavily influenced by Buddhism. A custom arose of priests placing rosaries around the necks of the dead bodies to protect them from kasha. Stones were placed on coffin lids to keep the corpses from rising up to ride in the fiery vehicle. Although that was no guarantee.

All of the appearances of this kasha were heavily influenced by Buddhism. A custom arose of priests placing rosaries around the necks of the dead bodies to protect them from kasha. Stones were placed on coffin lids to keep the corpses from rising up to ride in the fiery vehicle. Although that was no guarantee.

So how did this flaming cart from the sky become a cat?

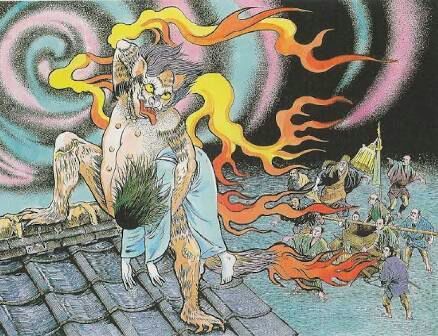

As with many yōkai, the origin of the cat-like form of kasha comes from artist Toriyama Sekien. When Sekien drew a kasha for the second volume of his Gazu hyakki yagyō (画図百鬼夜行; The Illustrated Night Parade of a Hundred Demons) in 1776, he drew a bizarre cat-demon covered in flames. Sekien often blended his own imagination in with folklore. He felt no shame in simply inventing things. For his illustrations in later volumes, he would write notes or stories discussing the creature in question, but for these earlier depictions he left only the picture and the name. We have no idea why he chose to make the kasha a cat.

Sekien’s influence on yōkai was so profound that people accepted the cat-like kasha and the stories began to follow. In Boso manroku (茅窓漫録; Random talk of outside cogon grass; 1833) a story was told of a funeral procession interrupted by a mighty wind and thunder that swept away the coffin as a kasha came down to retrieve the corpse. This kasha was not the flaming cart however, and was identified as a mōryō, a flesh-eating animal spirit, and was drawn resembling a cat.

In another book, Hokuetsu seppu (北越雪譜; Snow Country Tales; 1837), a story is told–said to come from the Tensho era (1573–1592)–where a funeral is interrupted by a gust of wind and a fireball that comes from the sky. Inside the fireball is a massive split-tailed cat (the calling card of the nekomata) that snatches up the coffin. But

the priest attending the funeral beats away the kasha with his staff.

Over time, this cat-form of kasha began to dominate. Like the nekomata and the bakeneko, kasha were said to be transformed house pets that lived an unusual span. Others said it was the presence of corpses that caused the transformation. A cat left alone too long with an unattended corpse would transform into a kasha and drag the body away. Fear of kasha became so great that when someone died the household cats were instantly banished, and coffins were even weighed down with rocks to prevent them from being dragged away.

As the kasha became more catlike, its influence spread to other kaibyō. Powers and stories were mixed and matched. Specifically, kasha and nekomata became blended. Nekomata inherited traces of the kasha’s appearance and necromantic powers. Some stories of nekomata show them with twin fireballs hovering over their split tails,

a leftover from the kasha’s flaming halo. Both kasha and nekomata were also said to be able to wake the dead. They could leap over coffins, weaving invisible strings and thus able to manipulate bodies like corpse puppeteers. Other rumors spread, but one thing was sure; when a person died, you had better kick the cat out of the room.

The association with cats and corpses seems grim, but it is not entirely without logic. Cats eating their dead owners is a real thing. Although it is rarely discussed, it is well-known amongst those who make the hauling of the dead their trade that if you die alone with cats in the house who are not being fed…well, cats do get hungry. The phenomenon is called postmortem predation. Dogs do it too, although they have more trepidations about feasting on their former masters and will wait a couple of weeks. Cats waste little time. After a day or two alone with a corpse, cats will start to chow down. If a person dies alone and the corpse is undiscovered for long enough,

the family pet might make a nice little feast and leave little to be discovered.

Because of this, it doesn’t take too much imagination to see how the flaming cart that comes from the sky to snatch bodies became mixed with the very real situation of corpse-eating cats.

Zack Davisson is an award-winning translator, writer, and folklorist. He is the author of YUREI: THE JAPANESE GHOST, YOKAI STORIES, and THE SUPERNATURAL CATS OF JAPAN from Chin Music Press, and an essayist for WAYWARD from Image comics. He lectured on translation, manga, and folklore at Duke University, UCLA, University of Washington, Denison University, as well as contributed to exhibitions at the Wereldmuseum Rotterdam and Henry Art Museum. He has been featured on NPR, BBC, and The New York Times, and has written articles for Metropolis, The Comics Journal, and Weird Tales Magazine.

As a manga translator, Davisson was nominated for the 2014 Japanese-US Friendship Commission Translation Prize for his translation of the multiple Eisner Award winning SHOWA: A HISTORY OF JAPAN. For Drawn & Quarterly, Davisson translates and curates the famous folklore comic KITARO. Other acclaimed translations include Satoshi Kon’s OPUS and THE ART OF SATOSHI KON, Mamoru Oshii’s SERAPHIM: 266613336 WINGS, Kazuhiro Fujita’s THE GHOST AND THE LADY, Leiji Matsumoto’s QUEEN EMERALDAS and CAPTAIN HARLOCK DIMENSIONAL VOYAGE, Go Nagai’s CUTIE HONEY A GO GO! and DEVILMAN: GRIMOIRE, and Gainax’s PANTY AND STOCKING + GARTERBELT.

January 6, 2018

Is Facebook a Safe Space to Grieve?

Even though I didn’t know Pepper*, her death impacted me.

I’d heard her name spoken in passing by my friend Elizabeth – their adventures, her yearly visits to Elizabeth’s home on the east coast, the mundane stories that sounded spectacular through the lens of “My best friend and I…”

I knew Pepper was sick, I knew there were hospitals involved. I knew Elizabeth was asking for “good thoughts and positive energy,” the language of social media we’ve become accustomed to seeing when loved ones are in trouble. From across an ocean, I knew Elizabeth was hurting, I knew the community around her was hurting, but I only observed it from the vantage point of Facebook. That is how I came to care about Pepper. Such can be the power of Facebook.

Shortly after those requests for positivity, I saw in my Facebook feed that Pepper had died. A lump stuck in my throat for a person I’d never met, a person I would never know. And despite being on complete opposite sides of the country – Elizabeth in New England, me in Hawai‘i – I witnessed Elizabeth mourning. I witnessed Pepper’s community mourning.

Shortly after Pepper died, her Facebook page was converted to a memorial account. For those of you who aren’t familiar, a memorial Facebook account is one where the owner has died, but the page can still be visited, and in some cases (depending on the privacy settings) friends can still post on the timeline. But a memorialized account will not appear publicly i.e. as a suggested friend to other Facebook users or on slight;y macabre birthday reminders.

A memorialized Facebook page is one that is very much frozen in time. That person’s last posts and photos will remain, and unless they appointed a legacy contact – someone who will run their Facebook account after their death – nothing will change.

In Pepper’s case, she would always be young, hopeful, and full of potential. I visited, and still do visit Pepper’s memorial page often (it is open to the public, or at least friends of friends). People write directly to her, telling Pepper they miss her, wish they were still doing the regular dinners, outings, goofy things. They wish her happy holidays and happy birthdays. Others write about her, write about the good times they had with her, how special she was, extolling her humor, her wit, her quirkiness.

When Pepper’s death was very new, Elizabeth, an artist and photographer, wrote a post that struck me in its intimacy as well as restraint – two things that don’t always pair well, if at all, on social media. Here was a person who was tired, hurting, but needed to express grief. And Facebook helped her do that.

Elizabeth chatted with me one afternoon, about her experience mourning Pepper on Facebook. “Grief is not tidy, grief is not quick, grief is not rational. Grief is so deeply misunderstood by the American public. I think seeing people in your immediate circle openly grieve a loved one can help teach people how to better empathize when someone you know is in mourning, and therefore how to be more sensitive, delicate, and patient when someone is grieving.”

And while Facebook has been criticized as being a minefield of “triggers” and “trolls”, Elizabeth, as well as many others, somehow find Facebook to be a safe place to publicly mourn. “It’s kind of intangible. I can’t explain exactly why Facebook feels safe. But thinking about my own experience and my own circumstances, the biggest part of it to me is that I interacted with was Pepper’s own page first, before it was a memorial. It was always a place we could reach each other, regardless of the distance between us. When I lived in Scotland, it was social media that connected us regularly since calls were too expensive to do regularly. So part of it just still feels like this is a really, really far distance, too far for calls or even responses. But it feels like I can still reach her directly there, silly as that may sound.”

Elizabeth too found value in the community the came forward after Pepper’s death.“The community aspect had so much value. Both from coming together with other people mourning the same person you are, and also just having access to the memories offered up by others – particularly when you live far away. I’ve really loved being able to have a visual history of other people’s memories of Pepper, moments in her life I may have heard about but never saw photos of.

I remember right after she died, I was at the hospital, sobbing in a hallway. I could barely form words aloud, but I had so much to say, so much that I was feeling. I remembered a portrait I had taken for an assignment in photo school while Pepper was visiting. I wrote a post – half as an update since I had asked people for good thoughts the moment I found out she was in the hospital, and half as a memorial announcement of her passing.

I posted that photo and not 10 minutes later her father found me and asked me for a copy because I had captured Pepper as he remembered her: beautiful, a little sassy, a little mischievous, but also strong and calm. That became kind of the official photo of her. It was used at her memorial, people were making prints of it, etc. And they would never have seen it without Facebook.”

But amidst the goodwill and affirmation that Elizabeth experienced on Facebook memorial pages, there are some that worry that Facebook grieving can devolve into a sort of “mourning Olympics”, with acquaintances staking a “claim on the effect of a tragedy”.

There can be a competitiveness in social media mourning that can become less about the person who died and more about who is (at least publicly) grieving the hardest. Wrote Lia Zneimer in Time, “Social media feeds into our desire to be the source of breaking information, to feel important, to be seen as knowledgeable and interesting. Endlessly retweeting tragedy becomes less about the expression of grief and more about wanting to prove we’re in the know and that we, too, were affected by the loss.”

When a dear friend tragically died a couple years ago, I found myself avoiding his memorial Facebook page. Not because I am any stranger to social media or public conversations about death or grief, but because I started to feel like people were coming out of the woodwork to make sure their sadness was counted. I stopped visiting the page altogether because I didn’t recognize my friend anymore, I’ll call him Brad, in the one-upmanship going on on the page.

Brad was a sweet, charming guy who didn’t have a lot of friends, but was generally liked by everyone. I rarely remember a time that anybody had a harsh word to say about him. But after the first wave of posts expressing shock and sorrow ebbed, a new “style” of posting emerged. Long, long posts from people many of us had never heard of. Some had had little to no interaction with Brad in years – online or otherwise. The language of the newer posts were flowery, indulgent, and chock full of platitudes. There was almost a “clubhouse” mentality of who Brad’s biggest mourners were.

While close friends and family enjoyed sharing stories that captured the essence of Brad – his goofiness, his gentleness – the emerging posts painted Brad as “Saint Brad”, completely washing away his humanity in favor of praising what may or may not have been true about him. A small group of us formed a private messaging group to get a break from the “Saint Brad Fan Club” and to share stories without feeling judged on the emotional performance of our posts. This was one experience for me where Facebook mourning did not feel safe. It felt like theater.

I’m not trying to dictate how people should mourn. We can’t be gatekeepers of people’s memory. But when grief collides with the artifice of Facebook, it’s hard to know how to approach either. On one hand, grief is intensely personal, sometimes impossible to verbalize, like Elizabeth said. On the other hand, “By design, social media demands tidy conclusions, and dilutes tragedy so that it’s comprehensible even to those only distantly aware of what has happened.”

When Claire Wilmot lost her sister, she was troubled, if not frustrated and upset by the postings on her sister’s Facebook. Wilmot wrote in The Atlantic, “The majority of Facebook posts mourning Lauren’s death were full of ‘silver linings’ comments that were so far removed from the horror of the reality that I found them isolating and offensive. Implicit in claims that Lauren was no longer suffering, or that ‘everything happens for a reason’ are redemptive clauses—ones that have a silencing effect on those who find no value in their pain.”

So what makes for such great disparity in Facebook mourning? What went into make Elizabeth’s experience so drastically different from Wilmot’s? Is it the cause of death? Was it the difference between a best friend and a sister? Was it an age difference that in turn affected how the community interacted with social media? (For the record, I don’t know how old Claire Wilmot is.)

Or was it just two different perspectives? Were there “Elizabeths” engaging on Wilmot’s sister’s page, and “Claires” avoiding Elizabeth’s posts?

It’s now been years since Pepper died. I still check in on her memorial page from time to time and it is still going strong. People still express sadness and longing, but more often than not people are sharing good things with Pepper. They remember her birthday, they tell her about births, they include her in celebrations. Pepper – her photo, her memory – was included in Elizabeth’s wedding.

It makes sense that for some this all might be too much. To be asked, or feel obligated to work through some very intense, complicated feelings in a public space can seem like a crude request.

Can mourning on Facebook ever feel completely safe? Does any public mourning?

But maybe (whether we like it or not) mourning on Facebook is becoming part of our cultural death education. By seeing others be vulnerable, we are less afraid or embarrassed to do so ourselves. By seeing other people engage with death, we as a society might be less inclined to live in denial.

*Names have been changed to protect identities.

Louise Hung is an American writer living in Japan. You may remember her from xoJane’s Creepy Corner, Global Comment, or from one of her many articles on death, folklore, or cats floating around the Internet. Follow her on Twitter.

January 5, 2018

Making your DEATH PLAN!

December 29, 2017

RIP YEAR OF CONTENT – A Tribute

December 21, 2017

Julia Pastrana’s Long Journey Home: A Conversation With Laura Anderson Barbata

Citation: Thr 1229.2.1* , Houghton Library, Harvard University.

In early 2013, an unusual journey took place. That February, the remains of a nineteenth century performer known as “the Ugliest Woman in the World” were removed from storage at the University of Oslo and repatriated to the Mexican state of Sinaloa, where they were given a dignified Catholic burial.

Announcement for the appearance of ¨The Misnomered Bear Woman,¨1856

Steam Job Press of McFarland & Jenks.

Credit: Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

A gifted singer and dancer, Julia Pastrana was born around 1834 with an unusually pronounced jaw and thick hair throughout her face and body. Though by all accounts an extremely pleasant person, her physical characteristics drew frequent comparisons to bears and other beasts. Her husband-manager exhibited her throughout Europe and the United States as “The Bear Woman—Half Human, Half Beast.” After her death in 1860, her embalmed body and that of her infant son were exhibited for over a century, appearing as late as the 1970s in US fairgrounds. They later spent decades in storage in Oslo, where they were vandalized, and her son’s body eaten by mice.

In 2013, after nearly a decade of effort, artist Laura Anderson Barbata succeeded in having Pastrana’s body repatriated to Mexico. The act drew worldwide attention as a measure of justice for Julia, as well as a small but symbolic triumph for human rights and women’s rights. As someone who has written about Pastrana, I was deeply impressed by Barbata’s tenacity in standing up to nations and institutions to accomplish her goal, and I wanted to ask her how she did it. A few months back, we spoke in honor of her new book The Eye of the Beholder: Julia Pastrana’s Long Journey Home (to which I also contributed). As we sat by the banks of Brooklyn’s Gowanus canal, we talked about the responsibility we bear to our dead, and the transformative power acts like repatriations can hold.

Portrait of Julia Pastrana, c. 1855–60; retouched daguerreotype

Julia Pastrana(1834-1860)

Alinari / Art Resource, NY

This interview took place on May 21st, 2017 and has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Bess Lovejoy: So how did you first discover Julia’s story?

Laura Anderson Barbata: I learned about the story of Julia Pastrana through my sister, Kathleen Culebro, who was producing a play here in New York—TheTrue History of the Tragic Life and the Triumphant Death of Julia Pastrana, the Ugliest Woman in the World, by Shaun Prendergast. She asked me to design the visuals for the first few minutes of the play, because the play basically unfolds in the dark. My sister had seen the play in London with my mother and they were affected by it, they felt it was an important story and they were shocked they’d never heard anything about her, being Mexican.

I was horrified and saddened just like everybody in the audience was, and my sister started a petition [to be] sent to the Mexican embassy in Oslo, requesting that Julia Pastrana be repatriated to Mexico and buried. Everyone who left the play signed it, it was sent, and that was it. My sister never received an answer.

BL: How did you go from being interested in her story to deciding to act yourself?

LAB: I signed the petition, but signing a petition isn’t enough. The play ended with Julia speaking to us from the basement of the Schreiner Collection [at the University of Oslo], where she was being stored. Sometimes it’s not enough to feel empathy—you have to actually act, right? I think that’s the purpose of empathy—it’s a driving force for activating change.

Because of my work in the indigenous communities of the Amazon, I was offered an exploratory trip to the north of Norway, where the Sami communities live, not long after the play closed. The Sami had been involved in repatriation efforts themselves with the Schreiner Collection, which has thousands of Sami skulls that were obtained illegally. So this was happening at the same time I was thinking about Julia Pastrana, and I observed what the Sami did and how the government responded.

This research continued when I returned home, but much more focused. A short while later, I was awarded an artist in residency in Oslo by the Office of Contemporary Art.

Julia Pastrana and her son embalmed in separate glass display cases, The Penny Illustrated Paper, London, 1862

Credit: Wellcome Library, copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only

BL: Who was the first person that you broached this with?

LAB: Dr. Per Holck, the curator of the Schreiner Collection. I wrote to him and said that I was interested in learning more about Julia Pastrana. And his answers were defensive—he said, “you can’t see her, she’s treated better than she would be in a church,” etc. I found his response strange: I never asked to see her, I simply asked a few very specific questions about her: why is she there, has anybody asked to see her, has anybody asked to do any tests? The official response was that “she’s there to serve science,” although no research had been done, nobody has had access to her, and no one had petitioned to see her.

BL: So who did you go to after Dr. Per Holck?

LAB: I went to the University of Oslo ethics department. They explained how the collection came to be built and how it operates . . . meanwhile, I was gathering information: reading, meeting people, having conversations.

I also knew that I had to be very careful because these issues are sensitive on many levels: it could have been an avalanche for institutions and museums to consider how they handle their own historical collections and mummies. So I knew that I had to be very careful and specific in order for the doors not to shut.

I was really just trying to understand the situation, but people around me were hoping that I would be able to accomplish the repatriation. Thanks to my friends, this happened. Every time I saw them they’d say, “Well, how’s it going?” They wouldn’t let it go. I felt exhausted, completely demoralized by the slowness, the complications, the bureaucracy of just trying to find out the facts.

BL: What were some of your next steps?

LAB: The National Committee for Research in the Social Sciences and the Humanities [NESH] didn’t know how to address the situation, so they decided to start a new board made up of citizen volunteers to review cases of the treatment of people after they’ve died … and Julia Pastrana became the first case for the board. They said that I could submit my letter as soon as the board was formed, but it took them two years to get organized. In the meantime, I had left Norway and I began consulting with experts about what to include in the letter, and I was doing as much research as possible.

BL: Was there one thing that you found specifically useful when you were learning about repatriation? One specific case?

LAB: Sarah Baartman [an eighteenth century South African woman exhibited as the “Hottentot Venus” in Europe whose remains were kept in a French museum for many years before being repatriated in 2002] was really important to me. Her case taught me many things at different moments. Initially, she was important as an example of a successful case, and that was encouraging. I could approach officials in Mexico and say “Well, Nelson Mandela intervened to get Baartman repatriated,” and that was proof that these efforts are important.

BL: So was the next step that the board actually convened?

LAB: Yes. I sent my letter and received a note that they [NESH] received and reviewed it. But the correspondence was sent by mail and it was lost; it arrived about one year later inside a plastic bag with a little note from the USPS that said “sorry that your mail was damaged.” So I just had to remain super-optimistic and focused on the issues at hand.

I was at the mercy of institutions that deal with objects, and I stayed focused on treating Pastrana as an individual. I started to do very simple things: I published an obituary in the local Norwegian newspaper because I’m sure she didn’t have last rites or an obituary.

And since she was a practicing Catholic, I went to St. Joseph Church in Oslo and explained her story and that of her baby. I asked if they could have a mass in memory of her. The priest said, of course, let’s do it. He said, “She’s a child of God, she needs this.”

LAB: So these restorative acts were very simple, but they began to change the chemistry of the relationships, and the way people saw her. When an audience walks out of a play, they may be moved and feel empathy, but they also feel powerless. But through simple acts it’s possible to change perceptions—from pity to dignity. And you start building on that, and helping people to feel that they can contribute to that. Otherwise, if we all wait for petitions, nothing’s going to change, we need to start changing things within ourselves and around us.

BL: So did the board ever get going?

Portraits of Julia Pastrana in dance attire, c. 1850´s

Citation: TCS 50 Pastrana, Julia 4, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

LAB: Yes, they were great. Essentially the letter in the plastic bag said: yes, we agree that Pastrana would not have wanted to be in a collection. But you have no claim on her, because you are not related to her, so thank you very much.

So then I thought, well, no problem, I’ll find a relative. There are many cases of hypertrichosis in Mexico and there’s an institute devoted to it. So I went to meet with them and they said it’s impossible to find a relative because we don’t have her DNA. No research had been done on her, there was not even a DNA sample.

And then I thought, but why do I have to be a relative to say that she should be treated with dignity? So that answer helped me, and I started articulating my whole approach from that perspective. This negative answer was the most positive one, because it’s very hard to debate our responsibility toward others.

BL: Meaning once you broached that argument, they weren’t able to shoot it down?

LAB: Right, because I was able to prove that people care, and it is our duty to defend the rights of others, especially those who don’t have a voice. This responsibility is not restricted to blood relatives only.

BL: What did they say?

LAB: Well, then a reporter from the Mexican newspaper Reforma, Silvia Gámez, became involved. At first I was cautious: I knew the story could become very political in Mexico. As a journalist she had to maintain a neutral position, but she broke the story in Mexico and it was one of the most widely read stories in the country, and was picked up by newspapers all over the world. This helped to prove that there was interest in Mexico.

And finally the NESH board said ok, we’re only an advisory committee, and we can’t demand that the university and the Schreiner Collection return her, but we can make a recommendation. And the Ministry of Health, who had initially made the recommendation that Julia go into the Schreiner Collection, also accepted the idea.

Meanwhile, I realized that I needed to make an even stronger case—I need somebody behind me … I needed my Nelson Mandela. I decided to approach the governor of Sinaloa because Julia Pastrana was born there. Sinaloa is a state that needs a positive story, since it has one of the highest rates of violence in the country.

BL: And you are from there?

LAB: I’m from Mexico City but I grew up in Sinaloa—I spent my childhood there, so I have a very special love for it. I contacted a historian, Ricardo Mimiaga, who was the only person I knew of who had done any research on Pastrana, and we went to see the governor of Sinaloa together. We asked him to write a letter to the board, as a representative of Mexico, and [saying] that in his official capacity he is requesting the repatriation of Julia Pastrana.

Everyone agreed—the board and the university, but the governor couldn’t be involved further because international relations are the responsibility of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. So the governor of Sinaloa made a formal petition, requesting the intervention of the embassy of Mexico that serves Norway—which is located in Belgium serving several countries.

And there’s another important point—Julia did not have a death certificate, so she couldn’t be handled as a person by a funeral parlor, or transported. Legally funerary services cannot do anything without a death certificate.

While I’m still organizing all of these details, I contacted a repatriation service. The university decided to have a ceremony for her, and this is a very important moment: it shows that they recognize the importance of treating her as a human being after being treated as part of a collection for so long.

And at the same time the Cultural Department in Sinaloa was preparing to welcome Julia, and part of that involved local funerary services, and addressing questions like where is she going to be buried, what kind of cemetery, is it protected, is she going to be robbed again? All these issues had to be solved.

BL: Just to go back for a minute, how does the actual “yes” come about? Who makes the final “yes,” if there is one?

LAB: The actual “yes” was from the university after they received the formal petition from the governor of Sinaloa, as well as a letter from journalist Silvia Gámez, a letter from me, the recommendation by NESH, and I understand that they also received one from Dr. Per Holck. The university agreed to the repatriation, but with some conditions: she should never be exhibited again, she should be buried and not incinerated, she should be given funeral services following her faith. Those were the conditions. And I thought: those are the best conditions, those are my conditions too! This is amazing.

I’m sure this was a very challenging process for the university. At the Anatomical Institute of the University of Oslo, Nicholas Márquez-Grant [forensic anthropologist, Cranfield Forensic Institute] and I, representing Sinaloa Mexico on behalf of the governor, confirmed that it was Julia Pastrana and witnessed as she was placed in her official coffin. Julia Pastrana was then transported to a private ceremony hosted by the university, at which the chancellor spoke with great respect and emotion.

Dr. Nicholas Márquez-Grant (left) and attendants from T. S. Jacobsen funeral agency with Julia Pastrana’s coffin, 2013

Photo: Laura Anderson Barbata

BL: And then her coffin was put on the plane?

LAB: Then her coffin was put on the plane. I wanted to accompany the coffin at every step because I was worried about what could happen, especially without a death certificate. But Albin International Repatriation company coordinated every detail perfectly.

She went from Oslo to Paris, then Paris to Mexico City, Mexico City to Culiacán—the capital of Sinaloa. They had a military arrival for her, and then she was driven to the military base, where a press conference was held followed by a small memorial. The following day, she was transported to Sinaloa de Leyva, where she was buried.

Julia Pastranas coffin being transported to the chapel at Rikshospitalet, Oslo University Hospital, 2013 Photo: Laura Anderson Barbata

There was a reception ceremony, and a lot of people came from neighboring communities, and there was a lot of press coverage. One of the most surprising things to me was the ways in which people responded to Julia and the signs they carried: such as “No more Julia Pastranas.” Her story also resonated with the violence against women and the missing women in Mexico. They connected Julia strongly to indigenous rights. The indigenous communities wanted her to be buried in their cemeteries, and while it’s true, she should have been, those cemeteries don’t have protection. They are at the center of a very problematic area in the state of Sinaloa, drug cartels are very strong and driving there is dangerous and difficult. It took some time to find the right cemetery that was close to where she was born, but was also secure.

So at the burial there’s the welcome committee, the governor spoke, and then everybody walked—this is a tradition—with the hearse and her coffin to the church for her funerary mass and afterwards continued the walk to the cemetery following a loud Sinaloan Tambora band to the cemetery where she was buried. I had started a campaign so that flowers could be sent from all over the world, but I never expected a truck full of white flowers for her. There were so many that they didn’t fit!

Julia Pastrana´s coffin in chapel at Rikshospitalet, Oslo University Hospital, 2013

Photo: Michaela Klouda

BL: What were some of the main things that you learned while doing this?

LAB: That justification for doing the right thing is our connection to other people, our humanity, not national or DNA connections. I already knew that, but it’s much more powerful than we give it credit for. And we need to really remember that.

But there’s a couple of other things that I think are really important: one of them is that you can, from wherever you are, make a difference. And it can take a long time, but you can contribute, and I think it’s our responsibility to contribute and correct injustices done in the past because we’re also paving the way for the future so that it doesn’t happen again—and that’s really why you do it.

And through this, you can enlist people into the opportunity. I think that’s the really important thing, making people feel like they’re part of this.

BL: Is there anything else you feel like you would want to say right now, in telling this story?

LAB: Your chapter outlines a couple of individuals that really do need to be repatriated. Nicholas Márquez-Grant, a forensic anthropologist, takes these questions on in the book and he admits that he was worried because a lot of his colleagues are against repatriation, because it means that an avalanche of bones are going to have to come out. But it doesn’t mean that. His text says you have to look at each case individually. I think they should not be forgotten and must be seriously evaluated.

BL: So what would you say to somebody who wanted to try to do something similar?

LAB: My recommendation is to approach it first with humility, it’s a complex issue. We don’t understand all of the systems that are operating, and we don’t want to close any doors. I think that’s the healthiest way, to be transparent and say: “I want to understand the situation. I feel a certain way about it, but I’m willing to suspend it to listen to you.” And then keep on learning from that. And persistence is good, surround yourself with people who believe in what you’re doing, sometimes more than you do.

Bess Lovejoy is the author of Rest in Pieces: The Curious Fates of Famous Corpses (Simon & Schuster, 2013) and an editor at mental_floss. She often writes about burial grounds of marginalized people, repatriated bodies, the history of bodysnatching in the U.S., and celebrity entrails.

Julia Pastrana’s Long Journey Home: A Conversation With Laura Anderson Barbata

December 15, 2017

ECO-DEATH TAKEOVER: Changing the Funeral Industry

December 8, 2017

FUNERAL FASHION

December 1, 2017

Managing Corpses After a Natural Disaster

November 30, 2017

The Odour of Sanctity: When the Dead Smell Divine

We moderns live in a sanitised blur of white smells, but scent was essential to our predecessors. Olfaction links us to our most primordial fears as well as our deepest desires. To the pre-Modern nose, time was marked with scent; sacred space was delineated with scent, the foul and the divine were understood by how they smelt. The link between offensive odours, the body, and immorality is well established in the psyche of Western society. The miasma that was thought to cause the plague was blamed as much on witches poisoning wells as on the immorality of the community leading to the fetid stink they believed caused death. Even today there are vestiges of Miasma Theory in the popular imagination, hence the frequency of lemon and lavender in Western cleaning products, two popular plague preservatives. It’s not really clean unless it smells clean. Our ability to smell connects us to the animalistic acts of the body, yet almost every religion also employs fragrance to create a sense of spiritual otherworldliness. Our ability to smell is exceedingly mundane and magical at the same time.

St. Therese of Lisieux’s body at her funeral

The putrefaction of the body has long been presented as theological evidence of the transient and base nature of the material world. Susan Ashbrook Harvey in her book Scenting Salvation recounts the tale of a monk in love with a woman that died and “cures” himself of his desire and grief by digging up her body, soaking his garments in the fluids found in her coffin and smelling the repugnant items whenever tempted. The moral of the story is clear. Earthly desires lead to nothing but the rot of the grave. While a siren song or a beautiful temptress may use superficial beauty to hide evil intentions, scent is much more straightforward. If it stinks it’s earthly and therefore wicked if it smells nice, it’s connected to the abstraction of the spiritual world and is therefore good. Yet, if corrupt smells are a sign of a corrupt nature, what happens when a holy person dies? It is in this Western mind-body dualism that the concept of the Odour of Sanctity is born.

The odour of Sanctity, formally known as Osmogenesia is a supernaturally pleasant odour coming from the body or wounds, usually after death. It was presented as a physical sign of the spiritual superiority of the person. While gods and supernatural beings are often associated with pleasant aromas, the Odour of Sanctity is attached explicitly to human bodies and is primarily a Western phenomenon. The concept arose in the early Middle Ages with roots in the early Christian communities of Greece and Egypt, but it didn’t gain considerable traction as a sign of sainthood in the Catholic Church until the early Modern Period. It wasn’t formally recognised as part of the beatification process until 1758 by Cardinal Lambertini (who later became Pope Benedict XIV) and has since been downgraded to a favourable sign of holiness. While the Odour of Sanctity is strongly associated with, and for a time was a sign of, incorruptibility the phenomenon was not limited to officially venerated saints in Catholicism or the Eastern Church and developed a robust apocryphal pedigree around heretic preachers and saints alike. Modern theologians will say that the Odour of Sanctity is metaphorical, that it’s an ontological state of being. While that may be true now or for religious scholars of the past, it indeed was taken, and preached, as a literal odour to the laity.

A dead body touched with the Odour of Sanctity can’t just smell ok. It has to possess the mysterious presence of a supernaturally pleasant odour. The scents can be brief or persistent, attached to the body, grave, water the body was bathed in, or objects the person touched. In the case of St. Padre Pio, his spectral scent of roses and pipe tobacco visited people after his death and was considered a sign of his saintly intercession. All Odours of Sanctities are described as sweet, with notes of honey, butter, roses, violets, frankincense, myrrh, pipe tobacco, jasmine, and lilies being the most frequently reported accompaniments. The scent is also always culturally specific and deeply intertwined with symbolism.

St. Polycarp the 2nd century Bishop of Smyrna was martyred by being burned at the stake. In the late Medieval telling of his death, his burning body was said to smell like a brazier of frankincense and myrrh instead of charred flesh. Thereby making an olfactive connection between the incense sacrificed in the Holy Temple, the gifts of the Magi, and Polycarp’s martyrdom. The eleventh century, Marie of Oignies’ body smelt of buttery pastries even though she sustained herself on nothing but communion wafers for the last few months of her life and died due to self-induced starvation.

St. Polycarp the 2nd century Bishop of Smyrna was martyred by being burned at the stake. In the late Medieval telling of his death, his burning body was said to smell like a brazier of frankincense and myrrh instead of charred flesh. Thereby making an olfactive connection between the incense sacrificed in the Holy Temple, the gifts of the Magi, and Polycarp’s martyrdom. The eleventh century, Marie of Oignies’ body smelt of buttery pastries even though she sustained herself on nothing but communion wafers for the last few months of her life and died due to self-induced starvation.

One of the most popular of the fragrant saints, St. Therese of Lisieux smelt of lilies, violets and roses upon her deathbed. Her most often attributed quotes is, “The splendour of the rose and the whiteness of the lily do not rob the little violet of its scent…If every tiny flower wanted to be a rose, spring would lose its loveliness”. It also should be noted that during Therese’s lifetime violet absolute was synthesised, making a material that was once the most expensive fragrance component in the world, affordable for all and the de rigueur fragrance of respectable women. To the Victorian pallet, violets represented chastity, modesty, and feminine virtue. Lilies and roses also have a long association with Jesus and Mary. Therese’s Odour of Sanctity creates an olfactive tableaux of Therese, the respectable modest female, alongside the Virgin Mary and Jesus. Before 1875 however, the scent of violets would not have been readily identifiable to the general populous, and no Odour of Sanctity is associated with violets in any primary sources before that time. There is also an active association between Osmogenesia and Stigmata, with the floral odour emanated from the wounds. Stigmatic Osmogenesia in every case is reported as the smell of roses, which again is deeply symbolic with the wounds of Christ.

While there is no way of knowing just how many people the Odour of Sanctity was associated with, in the Late Medieval and Early Modern periods ascetic mystics make up a large population of those afflicted with this post-mortem perfume. In particularly female mystics that lived cloistered lives. These women’s bodies suffered through harsh asceticism and self-inflicted mortification. Yet through the isolation, hardship, poverty, and virginity, these mystics sought to control their bodies and transform them into sacred vessels. It, therefore, makes sense from their perspective that, if successful, these discarded vessels of perfected souls should already be touched by a whiff of Paradise. The association of the Odour of Sanctity with cloistered women parallels the profane eroticism of the earthly woman with the chased eroticism of the sacred woman; while the worldly woman’s corpse corrupts by its nature and stinks, so the heavenly woman’s body remains pure and fragrant. However, the conversation is still about a woman’s body.

St. Teresa of Avila was another fragrant ascetic and mystic. She lived in seclusion, practised tri-weekly self-flagellations and didn’t wear shoes. The moment she died her bedside attendants said the room filled with the scent of roses that grew to saturate the building. The convent smelt like it had erupted into bloom and cascades of invisible blossoms poured from the windows. Her grave held the scent of roses for eight months. The sensuality of the story is part of the appeal. St. Teresa would never have done something so showy in life, but in death, the Odour of Sanctity makes it permissible as divine sensuality just as Bernini captures the divine sensuality of Teresa’s transverberation in the Ecstasy of Saint Teresa.

So what was it that all these people were smelling? If we couch the religious explanation, are there any earthly ones? Well, firstly many of the accounts of the Odour were written down centuries after the individual’s death and came out of folk traditions. So there is undoubtedly some gilded lilies. For others, the nose like any of our senses can be fooled especially when primed. In a time of sorrow and acute stress, a smell that was imperceptible moments earlier can become overpowering. One could rationalise the sickly sweetness of early decay or illness as divine honey. Of course, the more one tells a story, the more it turns to legend and becomes grander. So the whiff of sweetness becomes an eruption of flowers.

Rosa De Lima Painting by Jose Antonio Robles

What I think is of interest is the overlap of female religious ascetics associated with both the Odour of Sanctity and Anorexia mirabilis (the miraculous lack of appetite). Anorexia mirabilis was a form of religious anorexia that led women and girls during the late Middle Ages and early Modern periods to engage in prolonged fasts, not in the name of social acceptable beauty, but religious purity. These women abstained from eating for long periods of time or attempted to sustain themselves on communion wafers. Some, like Angela of Foligno and Catherine of Siena, refused food but reportedly ate the scabs and drunk the pus from sores of hospital patients. While they certainly were exceptions, their religious communities already practised fasting and food restriction to which a particularly devout practitioner could exploit while endangering themselves in pursuit of spiritual perfection.

In fact, the medical explanation for the Odour of Sanctity is that it is nothing more than Ketoacidosis. Ketosis is a natural process that occurs when the body runs out of glucose and starts to metabolise fatty acids. This progression volatilize acetone which produces a mildly sweet smell, unrecognisable to most. Should this devolve into the pathological metabolic state of Ketoacidosis from alcohol abuse, starvation or diabetes, the acetone becomes detectable, even overpowering. Someone engaged in prolonged fasts or dying while in an advanced state of Ketoacidosis would have a strong sweet smell about them.

In examining the lives of 18 women associated with the Odour of Sanctity, who lived over a 700 year period; all 18 practiced some form of food restriction while 10 entered into the pathological territory of Anorexia mirabilis. Seven cases either died due to self-induced starvation or illness complicated by refusing to eat, which supports the Ketoacidosis hypothesis. However, these women had many other similarities. 14 were mystics, 15 practised ascetic lifestyles, 14 were cloistered or hermits, 12 practised some form self-harm as self-mortification or stigmata.

This paints not only a medical profile but a social one. Seven of the cases were part of the Carmelite Order (6 Discalced, 1 O. Carm) 2 were named after St. Teresa of Avila who founded the Discalced Order. The Discalced Carmelites were also known for their extreme austerity. Even if Ketoacidosis wasn’t present at the time of death, it makes sense that women of the same order, leading similar lives, and looking to St. Teresa as a role model would also be associated with the same supernatural phenomenon as her at the time of their deaths. These women’s lives were dedicated to transcending their physical forms and nothing is more corporal then the haze of human decomposition.

It is perhaps their ultimate epitaph for them to have their corpses associated with the Odour of Sanctity. Personally, I’d prefer to lead a happy and healthy life and have the stench of my corpse reek to high heaven then to ever even attempt to achieve such perfection.

Some of the women associated with the Odour of Sanctity

Nuri McBride is a Research Fellow at the Minerva Centre for the Study of Law under Extreme Conditions, where she investigates how society, specifically, how the law, copes with mass death events and the refugees these events create. Nuri is a 5th generation Metaharet and has served her community for 15 years. She is also active in natural burial and death positivity education. As well as advocating for an inclusive approach to Jewish death traditions. While studying as journeyman perfumer in her free time Nuri started her blog which examines the use of olfaction in death rituals around the world. Follow Nuri on Twitter Instagram

Further Reading:

The Foul and the Fragrant: Odour and the French Social Imagination Alain Corbin [available in both French and English]

Scenting Salvation: Ancient Christianity and the Olfactory Imagination Susan Ashbrook Harvey

The Odor of Sanctity and the Hebrew Origins of Christian Relic Veneration Lionel Rothkrug

Odor and Power in the Roman Empire David Potter

Odor of Sanctity: Distinctions of the Holy in Early Christianity and Islam Mary Thurkill

The Odor of the Other: Olfactory Symbolism and Cultural Categories Constance Classen

Body and Soul: Essays on Medieval Women and Mysticism Elizabeth Alvilda Petroff

Le Parfum Comme Signe Fabuleux dans les Pays Mythiques Annick Lallemand In Peuples et pays mythique [French]

Parfums Magiques et Rites de Fumigations en Catalogne (de l’ethnobotanique à la hantise de l’environnement) Jean-Louis Olive [French]

Caitlin Doughty's Blog

- Caitlin Doughty's profile

- 8408 followers