Caitlin Doughty's Blog, page 20

June 28, 2018

WHAT HAPPENED TO PEARL HARBOR’S DEAD?

June 16, 2018

The Macabre, Unknown Origins of Father’s Day

Photo by Dale Sparks.

The Monongah Mine Disaster is recognized as the worst industrial disaster in U.S. history– and you’ve likely never heard about it. The disaster occurred in my hometown of Monongah, West Virginia. On the morning of December 6, 1907, at least 365 men and boys, ranging between the ages of 10-65 years old, died when two sudden and catastrophic explosions tore through conjoined mines #6 and #8. The report and quake of the blasts was said to be heard and felt for an estimated 10 mile radius.

Though 365 fatalities is the “official” death toll given by the company, it has always been understood among locals that the real death toll was much higher. There are many reasons for this false number, from the explosion being so volatile that many bodies were disintegrated on impact, to a quick and hasty cover-up so the mining industry could save face. Even the coal company acknowledged that it would be impossible to ever know the true number of men lost (though they did have a very accurate count of the horses and mules killed).

The disaster widowed over 250 women and left over 1,000 children without fathers or orphaned altogether. Grief permeated the entire region. Monongah’s mines were so large that many people in the surrounding areas worked or had family who worked within the two mines. Margaret Byington, a Red Cross worker involved with the relief aid in Monongah, described the place as a “…tragic little grey town, where sorrow meets one at every step…”

Enter Mrs. Grace Golden Clayton. In the summer of 1908, Grace Clayton suggested to pastor Dr. Robert Thomas Webb of Williams Memorial Methodist Episcopal Church South in Fairmont that a special service be held to honor and pay tribute to the legacies of fathers and paternal figures. Her suggestion was prompted not only by her grief for her own father’s death, but because of the disaster that happened barely six months earlier in Monongah.

Enter Mrs. Grace Golden Clayton. In the summer of 1908, Grace Clayton suggested to pastor Dr. Robert Thomas Webb of Williams Memorial Methodist Episcopal Church South in Fairmont that a special service be held to honor and pay tribute to the legacies of fathers and paternal figures. Her suggestion was prompted not only by her grief for her own father’s death, but because of the disaster that happened barely six months earlier in Monongah.

Grace Clayton was able to deeply sympathize with the sorrow that seemed to engulf the Monongah community. She was compelled to recognize their collective grief and to honor the hundreds of miners – fathers, brothers, sons, husbands, grandfathers, uncles, cousins, friends – whose lives were lost. So, on Sunday, July 5, 1908 (just a few months after the first observance of Mother’s Day, which took place just up the road in Grafton, West Virginia), the first Father’s Day service was observed in Fairmont.

There is some controversy as to where the idea for Father’s Day in the United States truly originated. After all, paying annual homage to parents has been a long standing tradition across the globe. Father’s Day has been celebrated in many different countries on different days long before the U.S. jumped on the bandwagon and made it our own retail and commercial extravaganza.

As for the U.S., credit for the establishment of the holiday is given to the state of Washington and Sonora Smart Dodd for a 1910 service held at a Y.M.C.A. This service was inspired by the successful 1908 Mother’s Day service in West Virginia. But that was a full two years after the first Father’s Day held by Grace Clayton after the mining disaster.

A major reason for this first-time event getting lost to history is its date: July 5th. The first Father’s Day was overshadowed by the Fourth of July.

Sorry, Dad. A sweet hot air balloon display and this dude who would balance on top of a giant ball while walking up and down a seven story spiral tower in the middle of the city totally stole your thunder. But, we didn’t forget you.

At the turn of the 20th century, Fairmont was a booming metropolis which boasted more resident millionaires and more religious and ethnic diversity than any other part of the country (not exactly what one thinks when considering West Virginia these days). The Fourth of July celebrations were all the rage, featuring week-long attractions with numerous revivals, traveling carnivals, sales, concerts, celebrities, parades, contests, and popular performers all building up to the major spectacle on the 4th. The residents and business owners of Fairmont went to great lengths to make the occasion free to the public in an attempt to lift the spirits of the community and provide a happy distraction from their grief (though I am not sure how much of a happy distraction the Monongah mourners actually got from the “two terrific explosions” at the end of the hot air balloon display).

Ultimately, Fairmont never insisted on getting the credit as being “the first”; instead, the focus is on recognizing both the dead and the mourners. This first service for fathers was not one of national promotion nor was it intended to be. Grace Clayton never promoted the service outside of the area, possibly not even to the local papers. More than likely, word about this service spread orally, given the majority of the target audience for this service would have been illiterate immigrants and children. Though she had every intention of honoring fathers everywhere, that first Father’s Day was a deeply personal and sorrowful experience. The sermon delivered on this occasion to mourners by Dr. Webb, has been forever lost.

Though the two mines in Monongah were back up and running by early February of 1908, the recovery and discovery of bodies and body parts continued for several more months, reportedly even as late as June of 1908. Remains found by this point were immediately “buried” within the mine. In result, for up to six months following the disaster, there were those who still harbored hope that the remains of their loved one might still be discovered, brought to the surface and identified so they could lay them to rest on their own terms. By the beginning of July it would have thoroughly sunk in to the majority of mourners that if something had not yet been found yet, it would never be. This first Father’s Day was, for many, the first and only funeral service they ever got for their lost dead.

Katie Orwig is a native of Monongah, West Virginia. She is a Jack of All Trades and a lover of history. She has a strong background in many Art Forms, is trained as a Death Doula, and is a strong advocate for Medical Aid in Dying in the U.S.A.

If you enjoyed this piece, please consider supporting our work. Your contribution goes directly toward running The Order, including resources, research, paying our writers and staff, and funding more frequent content. We’d love to keep pushing the funerary envelope in 2018. Visit our Support Us page, for a variety of easy ways to contribute.

June 15, 2018

7 Habits of Highly Effective Death Positive People

June 12, 2018

What Happens to a Body During Embalming?

June 1, 2018

DEMONIC BABIES: A Guide for New Parents

May 30, 2018

1918: The Forgotten Year of Death

In a single day, physician Victor Vaughan witnessed 63 soldiers die. Though it was 1918 and World War I still raged in Europe, these men had not been shot in the trenches or poisoned by mustard gas. They had died from an infection, just outside of Boston, at Camp Devens. And the disease was spreading.

Art by R.W. Harrison

By late fall of that year, Vaughan solemnly stated: “If the epidemic continues its mathematical rate of acceleration, civilization could easily disappear from the face of the earth.” Humanity did not perish that year, yet it’s easy to understand why Vaughan thought it could. International death toll estimates for the Spanish flu pandemic (that is, a global epidemic) range between 20 to 100 million, or about five percent of the world’s population, with cases on five continents. These fatalities included an estimated 675,000 Americans, or ten times as many who died in World War I.

On the centennial of this health disaster, it’s worth asking: why isn’t the 1918 flu better remembered? Loss scars our family trees. The visuals of that year remain haunting, with faces hidden by protective masks, and the streets left deserted as crowds became associated with death. Schools, theaters, and even churches were shuttered as people waited for the illness to pass. Schools and private homes were turned into makeshift hospitals, while a popular skip rope rhyme was ominously sung by children: “I had a little bird, / Its name was Enza. / I opened the window, / And in-flu-enza.”

Throughout history, birds have been linked to death. As omens of death in folklore, feared as carriers of deadly viruses, or in popular songs and rhymes like “In Flew Enza.”

Austrian painter Gustav Klimt, his protégé Egon Schiele, and French poet Guillaume Apollinaire, all died from the 1918 flu. Edvard Munch painted a “Self-Portrait after the Spanish Flu” in 1919, in which he is gazing haggardly at the viewer, drained but still alive. Even President Woodrow Wilson got the flu, its symptoms taking their toll as he participated in the 1919 negotiation of the Treaty of Versailles. Rich or poor, rural or city dweller, no one was safe from the Spanish flu.

In Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How It Changed the World, Laura Spinney notes that there “are very few cemeteries in the world that, assuming they are older than a century, don’t contain a cluster of graves from the autumn of 1918 — when the second and worst wave of the pandemic struck — and people’s memories reflect that. But there is no cenotaph, no monument in London, Moscow, or Washington, DC. The Spanish flu is remembered personally, not collectively.”

Emergency hospital during influenza epidemic, Camp Funston, Kansas.

There were three waves of the Spanish flu, with two in 1918, and a third in early 1919. “Spanish flu” is something of a misnomer. The countries involved in World War I were reluctant to publicize their own struggles with influenza, lest they be perceived as weak. Spain, however, was neutral, and didn’t censor this news. Scientists and researchers have theorized for years over the actual origin of the disease, from Camp Funston in Kansas, to China, with no consensus, except that it wasn’t Spain.

Wartime restrictions on communication had deadly effects, including in the United States. President Wilson’s Committee on Public Information and the Sedition Act passed by Congress both limited writing or publishing anything negative about the country. Federally-issued posters asked the public to “report the man who spreads pessimistic stories.” John M. Barry, author of The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History, writes in an article for Smithsonian Magazine about a particularly tragic consequence of this militant protection of morale. In Philadelphia, doctors pushed for the Liberty Loan parade on September 28 to be canceled, as they were concerned the concentration of people would spur the disease. “They convinced reporters to write stories about the danger,” Barry writes. “But editors refused to run them, and refused to print letters from doctors. The largest parade in Philadelphia’s history proceeded on schedule.” Two days later, the epidemic had indeed spread, and over just six weeks, more than 12,000 citizens of Philadelphia died.

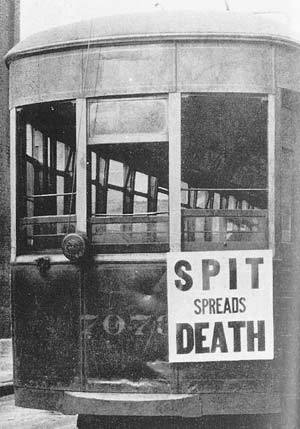

The Spanish flu is now identified as a form of H1N1 influenza. It still has outbreaks, but the clustering of soldiers in camps, the density of urban areas, and the newly global connections of ships, railroads, and other transportation, meant it had prime conditions for a pandemic in 1918. This was also before flu vaccines, and treatment options were limited. (Eating or wearing onions, drinking whiskey, and praying were some available prescriptions.) Posters issued by Alberta, Canada’s provincial board warned “there is no medicine which will prevent it,” and instead gave instructions on how to make a mask. A U.S. Public Health ad declared the disease “as dangerous as poison gas shells.” Shaking hands, borrowing books from the library, and spitting on the street were all warned against. In New York City, Boy Scouts patrolled the streets, handing spitters printed cards that read: “You are in violation of the Sanitary Code.”

Many infected people got better; many did not. In Flu: The Story Of The Great Influenza Pandemic of 1918 and the Search for the Virus that Caused It, Gina Kolata relates the grisly death by Spanish flu: “Your face turns a dark brownish purple. You start to cough up blood. Your feet turn black. Finally, as the end nears, you frantically gasp for breath. A blood-tinged saliva bubbles out of your mouth. You die — by drowning, actually — as your lungs fill with a reddish fluid.” And a significant number of the dead were not young or elderly — they were in the prime of their lives, between 20 to 40 years old, and generally healthy before they caught the flu.

Chart showing mortality from the 1918 influenza pandemic in the US and Europe.

As the sickness accelerated, there was a desperate need for doctors and nurses, many of whom were occupied by the war effort. Medical workers often contracted the flu, and there was reluctance to volunteer around this contagious disease. Then another crisis emerged: how to bury the dead. Alfred W. Crosby in America’s Forgotten Pandemic: The Influenza of 1918 chronicles the burial crisis in Philadelphia, where by mid-October the “problem of first priority was not a shortage of volunteers to keep the living alive, but the inadequacy of existing means to put the dead into the ground.” There weren’t enough coffins, and grave diggers couldn’t keep up. “One manufacturer said he could dispose of 5,000 caskets in two hours if he had them. At times the city morgue had as many as ten times as many bodies as coffins.”

At Dublin Union Hospital in Ireland, coffins were stacked 18-high in the mortuary at the pandemic’s peak. In Spain, the usual two to three-day-long funeral ceremonies were suspended, and village church bells, which had tolled for the dead since the 16th century, were stopped in order to not further demoralize the population. In Oklahoma City on the Sunday of October 13, the church bells were also eerily silent, as the city commissioners shut down the schools, churches, and any public space where the disease could spread. Just as World War I was splitting countries apart, the Earth was united under a dark shadow of death.

Some places were hit worse than others. In Western Samoa, now part of the independent state of Samoa, an estimated 22% of the population died. Māori people in New Zealand also suffered, with a death rate of about 50 per 1,000. Māori elder Whina Cooper, as quoted on the New Zealand History site, later described the horror at Panguru, Hokianga: “My father … was the first to die. I couldn’t do anything for him. I remember we put him in a coffin, like a box. There were many others, you could see them on the roads, on the sledges, the ones that are able to drag them away, dragged them away to the cemetery. No time for tangis [the Māori funeral rite].”

These cemeteries, whether in New Zealand or Kansas, are where we can remember the Spanish flu. There is no major Spanish flu monument, no Spanish flu museum. It’s likely you didn’t learn about the Spanish flu at school, even while studying the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinandand World War I. Go for a walk in your old local cemetery, read the tombstones, look for dates in 1918. You might find whole families who died within days, or maybe one big monument for a large field of grass, under which hundreds were interred when there was no time for individual headstones. There were unmarked mass graves dug for the pandemic’s dead — one was found during 2015 road construction in Pennsylvania — but many came to rest in these cemeteries, and are still there to discover and recall what popular history has forgotten.

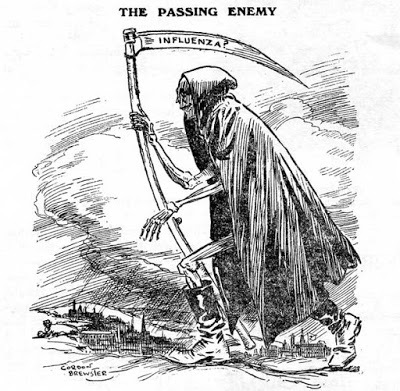

This cartoon by Gordon Brewster appeared in the Irish Weekly Independent of November 2nd, 1918.

No other epidemic or pandemic has claimed as many lives as the Spanish flu, not even the Black Death in the 14th century or AIDS in the 20th century. Its obscurity may be an urge to move on from this massive, seemingly inexplicable catastrophe. The individual losses were mourned, not the collective toll. Yet collectively is how people can make it through these disasters in the future, whether it’s getting a flu shot or supporting accessible healthcare to support a healthy whole. A flu pandemic could happen again. And unlike in wars, there are no winners in pandemics, only survivors.

Allison C. Meier is a Brooklyn-based writer focused on history and visual culture. Previously, she was a staff writer at Hyperallergic and senior editor at Atlas Obscura. She moonlights as a cemetery tour guide.

If you enjoyed this piece, please consider supporting our work. Your contribution goes directly toward running The Order, including resources, research, paying our writers and staff, and funding more frequent content. We’d love to keep pushing the funerary envelope in 2018. Visit our Support Us page, for a variety of easy ways to contribute.

May 25, 2018

BURIAL AT SEA

May 23, 2018

Sigrid Sarda’s Waxworks of Death and Desire

I first encountered Sigrid and her work during a time when I was deeply struggling with loss, grief, and identity. Her art acted as a balm, and helped me to continue facing sometimes painful and complicated questions. I love that Sigrid’s waxworks can evoke such conflicting emotions – they are enticing, yet make you feel quite uncomfortable. Beautiful, but somehow frightening. Are you compelled to stare or, look away? – just like sex, death and mortality.

When I learned she was working in New Orleans on a new series exploring grief, I was eager to learn more, so I reached out to Sigrid to ask her a few questions.

Vanité, The Maiden.

I know that before you began creating waxworks, you were primarily a painter. How and why did you come to work with wax as a medium?

In 1997 I was instrumental in helping my dad, who was my champion, transition comfortably into death. It has molded me into what I am today. The trauma associated with his dying acted as a catalyst in which I began creating new bodies of work made of wax.

Prior to that I painted. I lived in Paris and would sit at the Louvre weekly and study the Rubens and Gericault paintings to try and figure out the technique they used for flesh. Skin and flesh have always been a fetish of mine. I was painting a tryptic of Reese (my father) using the photographs I took immediately after his dying for reference. While working on a 6’ nude of him, I felt his guidance pushing through my paintbrush – all the techniques I wanted so dearly to learn happened in one fell swoop!

I returned to the states and my paintings began parring down, focusing on a single expression, i.e. a gazing eye or a drag queen’s fleshy finger with a chipped acrylic nail floating on a sea of blank canvas. Then I just stopped, having nothing more to say in that medium.

Then the passion for wax dolls, mannequins, effigies, reliquaries, nun’s fancywork, and anatomical waxworks sprouted. I began collecting and researching techniques used for various types of wax figures and life-casting. The first ‘waxworks’ were papier-mache dipped in wax obviously referencing wax dolls. As my interest expanded, so did my technique.

The obsession I have for wax comes from it’s quality. It’s fleshy and translucent, has a strength yet a fragility, not unlike that found in human nature whether corporeal or emotional.

Are there historical or cultural aspects about wax that inspire you?

I began creating life-size human figures made of wax incorporating human remains in the tradition of the doll as a magical object. The figures become talismans, reliquaries housing the human bones. The magical thinking we experience in childhood- something still very much part of me today- plays a vital role in the work, as does sexuality and human condition.

Religious iconography has made it’s mark on me since childhood. My mother used to say, how is it that at the age of six you were enthralled with images of a dying Jesus yet you were raised an atheist?! I think the wax mannequin has been of great importance as well. Being attracted to such beauty, one can find perfection in an early Iman wax head- something as women (and men) we find ourselves aspiring to be. Beauty and perfection- how silly!! But as silly as it may be we can’t deny that it’s ingrained in us all and how it affects our lives.

Why do you think some people find wax figures unsettling?

I suppose some folk find waxworks unsettling due to the uncanniness of the medium. If wax is done well the flesh looks real. The use of glass eyes and hair can bring the work to life. I’m talking about waxworks in general.

There’s such a rich history found in political/effigies, religious, magical, medical and entertainment – just look at all the horror films based on the wax museum- we like to be scared, so long as we feel safe.

Your new waxwork series is based on unrequited love and the five stages of of grief. Would you tell me a bit more (or, a lot more because I’m really excited about this project!) about the series and what you envision.

The Unrequited series is about loss and redemption. Redemption found within ourselves once we, not necessarily conquer an experience of loss, but grow and progress within that experience.

I tend to draw from the personal as well as the experiences of others, borrowing from fables, allegories and fairytales creating nightmarish vignettes of my own personal malaise blurring the lines of the assumption of the hero/villain and the universal concepts of archetypical imagery, while at the same time throwing in a lot of dark humor!

My reoccurring themes are about identity (Am I desirable or not? Do I fit in or not?), sexual identity, the roles between men and woman- role reversals, power and sex, life and death, antiquated and modernity.

The series love unrequited equates loss- something I know we all have felt to some degree. The five steps of grief, I think, helps identify the emotions that come into play. But it’s not cut and dry. There are a lot of layers going on when you’re looking at a work.

Sleeping Beauty, who portrays denial in the five steps, is in that crystallized state. Is she dead? Is she alive? What we can say for sure is that she is oh so oh alluring and sexual. She lays in the bed of crystals morphing into a crystal herself while she waits for that Mister Perfect that just doesn’t exist. At the same time she’s based off of the original Sleeping Beauty- where she was raped while in her state of repose by a king who happened to be passing through.

It’s interesting to see the reactions of men (especially if they are with a partner) when gazing upon this waxwork. I’ve seen them give furtive sideways glances, to down right staring. So yes, Sleeping Beauty is somewhat dead- in her emotions, waiting for Mister Perfect, her actually not being a living human, but yet she is so alive, a beautiful woman depicted in wax.

The blow up doll is anger, the working title is ‘I’ll make You Scream Like A Monkey! ‘. She is just so fed up of being used, abused and lied to.

Ophelia, depression in the series, dons a dress made of embroidered fresh water pearls in the form of Lily of the valley. Pearl tears wet her cheeks as she floats amongst the reeds bringing to mind a love full of hope and innocence. Even my Lothario, the villain, the straw man and emotional manipulator is a comical and sad character. The choice of all the materials used in each work is selected to represent, what I hope, a plethora of emotional responses the viewer can identify with.

Sigrid at work.

You recently shared some footage of your work on a stunning Ophelia figure for the series. Our society seems to be enthralled with imagery depicting beautiful, drowned women. Why? What does that reveal about us?

I’ve really been thinking about this question so I went around and asking strangers your question about beautiful drowned women and beautiful women dead in general, whether they were depicted in art, or graphic images found on the internet etc. Every single male response was “IF SHE’S HOT SHE’S HOT!” Didn’t make a difference if she were dead or alive. Death is still a major taboo/ fear in our culture. I think, too, it’s so much easier to immortalize and romanticize youth and beauty than to face the unknown.

Why did you choose to work on this particular series in New Orleans?

I chose to finish the series here in New Orleans for two reasons. The first being I feel at home here. There is depth in this city that one doesn’t find anywhere else in the country. It’s very similar to a European city. Death is also an accepting part of the culture here. The second is, the series is the precursor to my dream of dreams, which is opening an immersive attraction here in Nola.

From The Lodge’s Die Wunderkammer exhibit, 2013.

Sigrid is currently running a crowdfunding campaign, and creating a few new vanitas pieces that will be available for sale to fund her work on The Unrequited series. Also, did you catch that last bit?! “The series is the precursor to my dream of dreams, which is opening an immersive attraction here in Nola.” Let’s make this happen! You can help by sharing this piece, and/or the direct link to Sigrid’s campaign, which also features some fantastic perks, like original artwork, or the chance to spend the day with Sigrid in her studio where she will cast your own face in wax!

Click here to support Sigrid’s Waxworks.

For updates on Sigrid’s work, you can also follow her on Instagram.

Sarah Chavez is the executive director of The Order of the Good Death, and co-founder of the feminist death site Death & the Maiden. In addition to working as a museum curator she writes and speaks about a variety of subjects including the relationship between food and death, feminism and death, and Mexican American death history and decolonizing death rituals. You can follow her on Twitter .

If you enjoyed this piece, please consider supporting our work. Your contribution goes directly toward running The Order, including resources, research, paying our writers and staff, and funding more frequent content. We’d love to keep pushing the funerary envelope in 2018. Visit our Support Us page, for a variety of easy ways to contribute.

May 18, 2018

It’s a Mummy Unwrapping Party!

May 13, 2018

Motherhood on the Battlefield of Death

Childbirth was an important event among the Aztec/Mexica. Pregnant women were supported and attended to by tlamatlquiticitl, (midwives), who provided advice, medical care, and facilitated rituals intended to prepare the mother-to-be to take on the role of a warrior.

For Mesoamerican people childbirth was considered a form of battle, therefore, women who gave birth were revered as heroes and great warriors. “When the pregnant one already became aware of labor pains, it was said her moment of death had come to pass…and when the baby had arrived on earth, then the midwife shouted; she gave war cries, which meant that the woman had fought a good battle, had become a brave warrior, had taken a captive, had captured a baby.” (Florentine Codex 6:167)

Losses on any battlefield are inevitable, so women who died as a result of childbirth were given the same honor as men who fought and died in conflict. Both of these roles were deemed great sacrifices for the good of the community.

After her death the woman’s body and hair, which was left loose, would be washed, and she would then be dressed in her best clothes. The midwife would recite a prayer acknowledging her sacrifice, and praising the woman for her bravery:

Oh strong and war-like woman, much loved daughter! Brave woman, beautiful and tender as a dove. My lady, you have struggled and worked bravely, you have won. You are made in the likeness of our mother the Lady Cihuacóatl or Quilatzli. You have fought valiantly; you have used the shield and the sword bravely and struggled, using that which our mother the Lady Cihuacóatl Quilaztli has put in your hand. (as recorded by Sahagún (1829/1999))

When possible, her husband would carry her body to a special site dedicated to goddesses. Along the way he would be accompanied by the attending midwife, and the elder women of the community would arm themselves with swords and shields and perform battle cries.

Once they reached their destination, for next four days the deceased woman’s family and friends would watch over and defend her corpse from other warriors. According to Manuel Aguilar-Moreno the women became “such powerful beings that when a woman died in childbirth, her family had to guard her body carefully to prevent thieves from taking relics: the middle finger of her left hand, or her hair. Warriors believed that if they placed this finger or hair in their shields, it would make them stronger and braver, and blind their enemies.”

Finally, on the fourth day, it was believed that the teyolia, (the spirit or vitality of the individual), separated from the corpse and then continued on to an afterlife. Unlike many other belief systems, Aztec/Mexica afterlife destinations were not dictated by a person’s deeds carried out during their lifetime, but by the specific events of their death. In result, the teyolia of a warrior would transform into a spirit being and reside in a place of honor called Tonatiuh-Ilhuicac, the Heaven of the Sun. Here, they acted as escort to the sun, accompanying its daytime movements across the sky. Once four years had passed, male warriors would be reborn as butterflies or hummingbirds who could travel freely between the realms of both the living and the dead.

As for the women who died in childbirth, they would become goddesses called Cihuateteo, portrayed with skeletal faces as seen here.

It was the Cihuateteo’s duty to accompany the sun as it set, carrying it on a blanket fashioned from the feathers of colorful quetzal birds, while singing to the sun before gently depositing it in the underworld, or land of the dead, for its nightly respite – not unlike the women would have done for their own infants had they survived.

Cihuateteo were also permitted to visit the crossroads of the earth every fifty-two days. In great contrast to the men who became butterflies and birds, the women took on the form and demeanor of fearsome warriors. Transforming into a terrifying hybrid of human and beast comprised of a human body bearing a skeletal face, and full, youthful breasts which signified the fact that they were never able to nurse their babies. Their feet and hands were often depicted with sharp talons, their waists encircled by a belt adorned with a skull resting at the small of of the back, her loose hair swirling around a crown of skulls.

Aztecs/Mexicas constructed shines or temples at crossroads to honor the deceased mothers. As the fifty-two day mark approached, they would decorate the shrines with flowers and paper, and leave out gifts and offerings for the Cihuateteo, including food like tamales, breads or amaranth shaped into figures of butterflies, and corn.

Aztecs/Mexicas constructed shines or temples at crossroads to honor the deceased mothers. As the fifty-two day mark approached, they would decorate the shrines with flowers and paper, and leave out gifts and offerings for the Cihuateteo, including food like tamales, breads or amaranth shaped into figures of butterflies, and corn.

Today, some of the ancient statues of the Cihuateteo that appeared in shrines and temples, are on display at the anthropology museum in Mexico City and also in Xalapa, where they were found in a chamber with a larger-than-life size statue of a skeleton, as though they were companions or helpmates of death himself.

Spanish colonizers in Mesoamerica who were tasked with recording and relating information about “New Spain” to officials back home, did so with various biases and intentions. In several of their accounts they state that on the days when Cihuateteo visited the earth, that the people were deeply afraid of them and believed they would not only steal living children, but cause illness. This seems almost a contradiction to the veneration people held for these mothers upon their deaths. Demonization of Cihuateteo has continued with modern comparisons to “female vampires” who are out to seduce, trick, and entrap men, as well as kidnap children, but this misogynistic spin doesn’t have much evidence to support it.

According to scholar Anne Key, it is perhaps more likely that the colonizers, who were guilty of portraying “Mesoamericans as sub-human, therefore deserving of being enslaved, exploited, and abused by the conquistadors,” struggled with accepting female goddesses, and instead the Cihuateteo were “demonized, reduced, and characterized as malevolent specters,”* in their retellings.

Santa Barraza’s “Cihuateteo con Coyalxauhqui y La Guadalupana”

May our own future retellings of these lost women restore and acknowledge the reverence and respect they were given in death, in lieu of reducing them to common tropes that only value the female body if it can serve society by carrying out maternal duties, be sexualized, or serve as a scapegoat. Our society places women’s bodies in a strange and unique liminal space between life bearer and death bearer. According to Dr. Tomi-Ann Roberts, “I find that it is hard to think about the fact that lactation, childbirth, and menstruation are all about giving life, and yet they are reminders of corporeality, our animal nature and mortality. So women, in being able to give life, have been considered across time and culture as bearers of death.”

These women died during the act of creating something that bore their hopes and dreams for themselves, the future, and their community. In their memory let us embrace and celebrate the archetype of the mother in all of us – as a brave warrior, creator, and bearer of both life and death.

Sarah Chavez is the executive director of The Order of the Good Death, and co-founder of the feminist death site Death & the Maiden. In addition to working as a museum curator she writes and speaks about a variety of subjects including the relationship between food and death, feminism and death, and Mexican American death history and decolonizing death rituals. You can follow her on Twitter .

Additional Resources

The bulk of this piece is based on the research and work of Anne Key.

*Key, Anne. “Death and the Divine: The Cihuateteo, Goddesses in the Mesoamerican Cosmovision.” PhD diss., California Institute of Integral Studies, 2005.

Sahagún, Fray Bernardino. Florentine Codex: General History of the Things of New Spain. 12 vols. Translated by Arthur J. O. Anderson and Charles E. Dibble. Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research and University of Utah Press, 1950–82.

Aguilar-Moreno, Manuel. Handbook to Life in the Aztec World. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Cihuateotl, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Call the Aztec Midwife, National Geographic

The Aztec Women Who Became Goddesses After Dying During Childbirth, Cultura Colectiva

Giving Birth Was One Big Battle, Mexicolore

If you enjoyed this piece, please consider supporting our work. Your contribution goes directly toward running The Order, including resources, research, paying our writers and staff, and funding more frequent content. We’d love to keep pushing the funerary envelope in 2018. Visit our Support Us page, for a variety of easy ways to contribute.

Caitlin Doughty's Blog

- Caitlin Doughty's profile

- 8411 followers