Caitlin Doughty's Blog, page 16

December 20, 2018

Considerations for Caregivers in Marginalized Communities

In 2013, when my mother was diagnosed with Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD), I became her full-time caregiver. Frontotemporal Dementia is a rare disease related to Alzheimer’s that is characterized by major shifts in personality and is the most common form of dementia for people under the age of sixty (TheAFTD.org 2018). I was in my late twenties when I left my job in healthcare to care for my mother full-time. Upon my leap into the world of family caregiving, I made some alarming discoveries around accessibility and inequity within healthcare. Caregiving is already extremely overwhelming; members of marginalized groups experience additional stressors that make things even more difficult.

Aisha Adkins, Founder of Our Turn 2 Care.

The Breakdown (Source: AARP.org)

In 2015, there were 65 million informal caregivers in the United States — that’s 29% of the population. On average, these caregivers spend an average of 20 hours per week caring for a sick family member or friend. About two-thirds of family caregivers are women. But those figures represent that majority. Caregivers fill the margins of society as well. Thirteen percent of caregivers are African-American; half that amount are likely to belong to the sandwich generation with parents living in the home. The highest rate of caregiving for the family is fund among Hispanics at 17%. Asians represent 6% of the caregiving population, members of the LGBTQ community make up 9%, and 14% of caregivers fall between the ages of 18 and 41 (Source: Caregiver.org).

Race + Orientation

Someone in an online support once responded to my post polling minority caregivers by asking me what race, sexual orientation, and gender identity have to do with caregiving. The poster was both annoyed and outraged at the suggestion that caregiving experiences vary based on these classifications and exclaimed “Isn’t it the same for everyone?!” I responded “No,” and promptly blocked her.

The reality is that, as isolating as caregiving can feel at times, it does not take place in a vacuum; external factors can greatly impact the caregiver on an economic, historical, or a sociological level.

Here is a bit of a breakdown on demographic-specific challenges and concerns of minority caregivers:

LGBTQ

Fifty-one percent of LGBTQ caregivers are more concerned about money [than straight caregivers] and 32% are report struggling with loneliness. Nearly one-third of LGBTQ caregivers fear having no one to take care of them as they age or if they become ill; and 20% of Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual caregivers, along with 44% of transgender caregivers, are afraid that a bad relationship with healthcare providers if they knew their orientation or gender identity. Members of the LGBTQ community are twice as likely as straight caregivers to grow old single.

African-Americans

Overall, the Black community contains the most number of family caregivers, with 21% of African-Americans providing care for a loved one. Most Black caregivers belong to the sandwich generation and are therefore more likely to live with the person in need of care. Living with their loved one also means that Black caregivers are more likely than white or Asians to assist with Activities of Daily Living (e.g. bathing, dressing, feeding, et cetera).

Hispanics/ Latinx

The Latinx community shares many of the caregiving hardships of African-Americans. Both communities experience greater burdens and experience a higher rate of caregiving than white or Asian caregivers at 21%.

Financially Challenged

Caregiving families’ median incomes are 15% less than families who do not include caregivers. The poverty rate is higher among families with disabilities, and 47% of these caregivers report having used up their savings.

Intersectional Hardship

People of Color people living at or below the poverty line are more likely to experience poor health and lower rates of literacy. Regular stress has an adverse effect on one’s aging; caregiver stress can take a much as 10 years off of one’s life. One-fifth of family caregivers have had to take a leave of absence.

Physicians & Cultural Competency

For the Culture

Cultural competency refers to how well someone knows about the values, traditions, and beliefs of a culture that is different from their own. In healthcare, Brown University defines cultural competency this way: “Understanding how culture and ethnicity can affect the care they deliver.” According the MD Edge, there are a lot of unfair differences in healthcare, including racial bias, unfamiliarity with religious practices, and language barriers.

Speaking Your Language

Language can have a major impact on the quality of care patients receive. The Hospitalist reported that 14% of people living in the U.S. speak something other than English at home, which leads to increased potential for medical error. While many large hospitals provide translators for one or more languages, translation services are not always available at smaller or more rural facilities.

When children who speak both English and the language of their parents act as translators “it distorts family roles and makes the children uncomfortable” (The Hospitalist). Awkward situations may occur when parents ask their children to help them fill out medical history forms or when the physician asks questions about adult subject matters. Both children and parents may feel uncomfortable handling personal questions about addiction or sexualy activity. This discomfort may cause parents to leave things out of their medical history or answer the doctor’s questions dishonestly, which may lead to potentially life-threatening consequences.

Awkward situations come up when patients and doctors do not speak the same language, but gender can also play a major role in the quality of patient care. Some cultures or religions have very strict guidelines about interactions between men and women, including things like touching, making eye-contact, or wearing clothing that cover specific parts of the body. If a doctor is unfamiliar with these expectations and unintentionally violates the patient, it could lead to challenges including shaming or shunning within the family or community, or other traumatic effects.

History

Many Black families recall times when the healthcare system violated the public’s trust, like the cases of Tuskegee Experiment or Henrietta Lacks. These events have lead to a mistrust of medical professionals for some in the Black community, making its members less likely to seek regular medical treatment.

How Do We Fix It?

Caregiving can feel really lonely at times and you may be afraid to speak up. But, as Whoopi Goldberg’s character said in an episode of “A Different World,” You Have a voice in this world, and you deserve to be heard. To make sure that your and your loved one’s concerns are being heard, the following tips may help you get your point across:

Get a Translator

As a part of the Affordable Healthcare Act passed by the Obama Administration in 2010, healthcare providers are required to provide language interpretation services for patients with limited English proficiency (LEP). If the doctor speaks a different language from you and/or your loved one, it is your right to request an interpreter services. At most major hospitals, there will be a department that provides translators and offer important documents in several languages.

Ask Again

If a doctor or other healthcare professional says something that you do not understand, it is totally okay to tell them that. Say: “I don’t understand what that means. Please explain it again.” After all, this appointment is about your loved one and making sure everyone understand what’s going on with their care.

Demand Respect

If you understand your doctor but feel like their tone or attitude is disrespectful, it’s alright to tell them that as well. Maybe you notice the doctor seems to have a problem with you or your loved one’s race, class, or sexuality. When this happens, you can say “I understand that you are the physician, but I do not appreciate the tone you are taking with me. We will be spoken to with respect.”

If all of this still sounds kind of scary, don’t worry. There are people whose jobs are to help you stand up for your loved one’s healthcare rights. A great place to start is with your local chapter of the Patient Advocate Foundation. Some things may feel awkward or uncomfortable at first, but the temporary discomfort is worth your loved one getting the best care possible, and you getting the caregiving support you need.

Read Part One of this two-part series on caregiving here.

Aisha Adkins is a writer, caregiver, advocate, graduate student, and speaker based in Atlanta, Georgia. A graduate student at Georgia State University’s Andrew Young School, this authentic storyteller is driven by faith, inspired by family, and eager to use her talents to affect positive social change. She is a full-time caregiver for her mother and founder of Our Turn 2 Care. When she is not a doting daughter and agent of change, she enjoys classic film, live music, and nature.

If you enjoyed this piece, please consider supporting our work. Your contribution goes directly toward running The Order, including resources, research, paying our writers and staff, and funding more frequent content. We’d love to keep pushing the funerary envelope in 2018. Visit our Support Us page, for a variety of easy ways to contribute.

December 12, 2018

Surprise, You’re Going to Be a Caregiver – Part I

Maybe your father suffered a stroke and you go to sit with him for two hours every morning and drive him to physical therapy every Thursday. Perhaps your auntie is having some problems remembering to take her medicine so you stop by every day on your way home from work. Or maybe you left your job and are going to move in with your grandmother who recently broke her hip after falling in the shower.

Do any of those scenarios sound familiar? Then you are indeed a caregiver.

How Does That Make You Feel?

When you first find out you’re going to become a caregiver (or slide into that caregiving role without even realizing it), you’re probably going to experience a range of emotions. Fear, anxiety, anger, frustration, honor, pride, or complete and utter cluelessness. If your loved one’s diagnosis is terminal, you may experience symptoms of grief as well.

Whatever you feel in this moment is not wrong. It’s not about the emotions themselves, but your reactions to them. In a situation where you’re inclined to focus solely on the person you’re caring for, you have to be sure to check in with yourself first. It’s like that famous airplane analogy: in an emergency situation, you have to put oxygen on yourself first before you can help anyone else. Figuring out how you feel and what you need to be okay is fine. Caring about yourself isn’t selfish.

The Starting Line

Caring for a family member, especially someone older than you, can be awkward. Caregiving can come with duties, responsibilities, and conversations that are just plain uncomfortable. As a result, a lot of families put off talking about the uncomfy stuff, like advanced directives, wills, or money because they dread feeling awkward. Newsflash: feelings can’t actually hurt you, but being unprepared very well might. One way to work through your feelings is by taking action.

One of the single most important things a caregiver needs (especially those caring for someone with a progressive or terminal disease) is Power of Attorney (POA). There are different kinds of POA, but it basically gives the caregiver permission to make decisions about the loved one’s care when they are unable to do so for a short or long period of time. This document allows the caregiver to make decisions on things like how to manage the loved one’s pain to whether or not to perform CPR on someone when they stop breathing. Power of Attorney may sound really heavy, and that’s because it is. But without this document, caregivers are really limited in terms of the info they have access to and the decisions they are legally allowed to make. Having this one document can make a huge difference on the care your loved one receives so it is very important for the primary caregiver (the one providing most of the care) to get it as soon as possible.

A simple Google search will bring up the proper Power of Attorney for healthcare form in your state or country.

The Setup

Some caregivers may be shocked by how little help or support they have from family members. Siblings you thought would be more involved in the care of your loved one may fail to do their fair share or may bail completely. That is why it is important to identify the roles everyone will play. Someone will be the primary caregiver, providing care daily or weekly care most of the time. Someone else may provide transportation. Another person may do the grocery shopping, while another still may handle the bills. Unfortunately, some caregivers find that people they’d hoped would help them out, end up not being so reliable. You call for help, but they are always mysteriously “unavailable.”

The absent sibling or cousin is not unusual. But going back-and-forth about how terrible the other person is will be a waste of time and does not help your loved one. That’s why it’s important to identify the dead weight in your circle and cross their names off the list of helpful helpers. Again, it is going to be awkward, but it will make your life much easier. Once you’ve figured out the people and resources that will actually help you, you can divide up your responsibilities between reliable family members, friends, neighbors, local nonprofits, places of worship, and medical team.

Once you’ve figured out who will do what, write it all down and make sure everyone understands their roles. Communicating well and often will make care run more smoothly and your loved one will be better off as a result.

Technology makes it a lot easier to make sure everyone is on the same page – literally! Shared calendars on platforms like Google Calendar and Apple iCal allow users to create individual calendars for everyone on the care team and lets everyone access one “master” calendar. Features like color coding and reminders keep everyone organized and being able to see everyone’s personal schedules makes scheduling easier. Of course, it’s always good to have an old-fashioned wall calendar or datebook as a backup plan if technology fails (because it will). Remember: Update one calendar, update them all. Sometimes it may seem like overkill, but it’s better to have too many reminders than to miss important meets due to miscommunication.

The Beginning of the End

Taking care of another whole, grown-up human being can be overwhelming and it may be tempting to put tasks off and just address them as they come up. But caregiving can be as unpredictable as it is overwhelming. That’s why it is important to talk and think about what your loved one wants for the end of their life. One way to start the conversation is to find out if they have a will and/or advanced directive. These documents are really important because they tell you exactly what to do for the loved one (e.g. leave them on life support, cremate their remains, scatter their ashes at their favorite park, etc.) and what to do with their estate (e.g. who gets Grandma’s favorite gold pin, what charity should get all of Auntie’s old clothes, how do we split up the funds in abuelo’s bank accounts, etc.).

Depending on your loved one’s condition, it may seem pointless to talk about this stuff; their disease isn’t deadly and they can still think for themselves, so why get all morbid? Because life is unpredictable. There are cases where people diagnosed with terminal illnesses survive against the odds, but there are also cases where otherwise healthy people end up dying unexpectedly. Dealing with the ill, the aging, and the dying can be really difficult – especially when it’s someone close to you. But the more prepared you can be, the more room you’ll give yourself to grieve and mourn the way that is right for you, without all of the guesswork it takes trying to figure out what your loved one would have wanted you to do.

No Matter What

Throughout the caregiving process, you will hear voices (either in your head or actual voices from other people…) that will comment on how you’re doing. Therefore, I’d like to leave you with the following reminders:

You are a good person and you’re doing the best you can.You will not get everything right. Because you’re a human. And humans make mistakes. Fix what you can fix and keep on moving.

You know your loved one. You may not know everything about them, or maybe the person you’ve always known has been changed by illness. But, at the end of the day, if you think something is wrong or are concerned your loved one isn’t getting the best treatment, don’t be afraid to speak up! It could be something as simple as adjusting their pillow or something bigger like challenging a diagnosis. Whatever it is, as long as you have your loved one’s best interest at heart, you’ll never be doing the wrong thing.

Don’t sweat the small stuff. Seriously. Nothing in life is perfect. That is especially true in the world of family caregiving. Dinner may not always come out the way you wanted it and your schedule will be thrown off every now and again, but you can’t let life’s interruptions ruin your entire day. Acknowledge that the plan has changed, don’t worry about who’s to blame, and move onto the next thing. A balanced attitude will help you avoid stress for yourself and your loved one.

Whatever your caregiving situation looks like, there’s no need to be ashamed or embarrassed. Taking care of someone who can no longer care for themselves is an amazing thing. Not only are you helping them with the physical tasks of daily life, you’re helping them live their lives with a bit of dignity and compassion. You’re letting them know that just because they are sick, and their lives as they once knew them have changed, they are still whole, human, valued.

Aisha Adkins is a writer, caregiver, advocate, graduate student, and speaker based in Atlanta, Georgia. A graduate student at Georgia State University’s Andrew Young School, this authentic storyteller is driven by faith, inspired by family, and eager to use her talents to affect positive social change. She is a full-time caregiver for her mother and founder of Our Turn 2 Care. When she is not a doting daughter and agent of change, she enjoys classic film, live music, and nature.

If you enjoyed this piece, please consider supporting our work. Your contribution goes directly toward running The Order, including resources, research, paying our writers and staff, and funding more frequent content. We’d love to keep pushing the funerary envelope in 2018. Visit our Support Us page, for a variety of easy ways to contribute.

December 9, 2018

America’s Most METAL Cemetery

DEATH IN THE AFTERNOON PODCAST – Ring Ring, Corpse Phone: SEASON 1: EPISODE 8

Welcome to our eight and final episode of of season, Ring Ring, Corpse Phone

Episode description: Ring ring. Hello? Who’s there? IT’S YOUR MORTALITY CALLING. In life, phones make everything easier– just “reach out and touch someone.” But in death, reaching out can be a little more complicated. This week we talk about accessing a dead man’s cell phone, texting from beyond the grave, and the grim origins of a certain red handset.

Here’s Louise for our final podblog of the season:

For our last “behind-the-scenes” blog of this first DITA season, I thought I’d share what it was like for me to work on this podcast. I’m super duper proud of what we birthed onto the airwaves but I’m not going to lie, this was new nerve-wracking territory for me. Like most good things are.

It’s no secret that I’m the latest member of our little Order triumvirate. Caitlin and Sarah have been a team for years now, and a couple years ago I was lucky enough to get invited to play on their team. Yes, dream job.

I won’t wax poetic about how great Caitlin is, you already know this (and she’ll delete it); and all I have to say about Sarah is that you’d be lucky to find a peer half as smart and kind as her in your lifetime. Plus she is the keeper of all the bonkers death stories.

So when Caitlin proposed that we three do a podcast, I was at once thrilled and terrified.

I was going to have to SPEAK OUT LOUD on the same show as the Caitlin and Sarah?

I knew I had things I wanted to expound upon as well as the ability to form audible sounds that humans interpret as language, but it’s one thing to talk deathy things with my friends and coworkers or write scripts and articles about Bentham’s head or morbid mysteries, it’s another thing entirely to talk to the masses.

Out loud.

For days leading up to my first rehearsal with Caitlin, I had nightmares about completely outrageous SECRET meetings where Sarah and Caitlin contemplated replacing me with a goat or a moderately educated waffle.

I went into the first rehearsal feeling both over and under prepared. I could talk circles about rogue limbs, but I felt like I had lost all control of phrasing and the VOLUME of my VOICE. Like the Shel Silverstein poem all the “What ifs” were dancing in my head.

What if I don’t make sense?

What if my speech impediment comes back?

What if I sound like a robot?

What if all my research is wrong and I tell the world bad knowledge and all the corpses explode?

But very quickly (as I should have known it would go), I realized that part of my anxiety was hilariously unfounded.

My job on the podcast is to talk to Caitlin. I do this often. Yes, we had to focus on embalming blunders or disembodied feet and not run off on tangents about the deliciousness of cold pizza versus hot pizza but Pop Tarts on the other hand –

– point is, I can talk to Caitlin. Sure we had to find a “podcast rhythm” and chemistry, but I quickly realized that the intimidation was in my head. Talking about corpses with Caitlin comes naturally. Plus, if my information was wrong, there was no way that Sarah or Caitlin would let it slip by. Hello, that’s working on a team Louise. (I swear I’m not trying to get you to join our cult…OR AM I?)

So rehearsals continued and I gained confidence.

Then we got to recording.

I don’t know if any of you have ever worn headphones and had to listen to your own voice, and then have your voice recorded and played back to you over and over and over. If you aren’t used to it, it’s…an adjustment. You never sound the way you think you’ll sound, for better or for worse.

So many times I would glance into the booth as words about Okiku or standing corpses tumbled from my mouth and wondered if everybody in there was figuring out ways to engineer my voice into submission.

It’s weird to think so intensely about the simple act of speaking! Like, if you think too hard about walking, you’ll fall down (just me?).

But we finished recording and in spite of my concerns, I found myself enjoying the process. SHOCKER it was fun to gab death with two people I like and admire.

Eventually the episodes aired, as podcasts tend to do. I braced myself the first time I had to listen to the master of episode 1. Sure, I had to ride the initial wave of The Big Cringe but I didn’t incinerate on the spot.

Now, eight episode later I look forward to hearing the final edits. Not to wrap this up in too tidy of a bow, but looking at how I started into this journey and where I ended up – I can’t believe I did it. And I wasn’t replaced by a goat!

So thank you for listening to Caitlin, Sarah, and me for these eight weeks. I am so proud of the death conversation we put out there – sometimes difficult to hear, sometimes heartwarming, sometimes straight-up beyond belief. But when all is said and done and uploaded onto iTunes, I’m so happy I get to be a part of this squad.

So thank you for listening Death in the Afternooners, it was a pleasure.

Our heartfelt gratitude for your enthusiasm and support for our first season! Stay up to date and get even more behind the scenes goodness from Death in the Afternoon over on Twitter and Instagram. Follow us – let’s be friends…’til death.

From the Death in the Afternoon team,

Caitlin, Sarah, Louise, Dory, and Paul

Death in the Afternoon Engineer, Paul Tavener, and Editor and Composer Dory Bavarsky!

Death in the Afternoon is a podcast written, researched, and developed by Caitlin Doughty, Sarah Chavez, and Louise Hung of The Order of the Good Death.

Caitlin Doughty is a mortician and funeral home owner in Los Angeles, CA. Along with Sarah and Louise she runs The Order of the Good Death and the Good Death Foundation, orgs that spread the death positive gospel around the world through video series like Ask a Mortician, blogs, bestselling books, and now, a gosh darn podcast!

Sarah Chavez is the executive director of The Order of the Good Death. As the child of parents in the entertainment industry, she was raised witnessing choreographed Hollywood deaths on soundstages. Her work has been influenced by her unique life and weaves together the relationship between death and food, feminism, Mexican-American death rituals, and the strange and wondrous history surrounding the culture of death itself.

Louise Hung is a writer, researcher, and community manager for The Order of the Good Death. While she can usually be found hunched over her computer working on video scripts for Ask a Mortician, Louise has also been known to tap out a few words about death in folklore, history, pop culture, and Asian or Asian American communities.

Guest Writer: Allison C. Meier is a Brooklyn-based writer focused on history and visual culture. Previously, she was a staff writer at Hyperallergic and senior editor at Atlas Obscura. She moonlights as a cemetery tour guide.

Editor and composer: Dory Bavarsky

Engineering: Paul Tavener

***EPISODE TRANSCRIPTION COMING SOON

DEATH IN THE AFTERNOON PODCAST – Ring Ring, Corpse Phone: SEASON 1: EPISODE 8

November 30, 2018

DEATH IN THE AFTERNOON PODCAST – Or Maybe, it’s a ghost?: SEASON 1: EPISODE 7

Welcome to our seventh episode, Or Maybe, it’s a Ghost?

Episode description: A wisp of white. A voice in the dark. A toilet mysteriously flushes by itself. Few things capture our imagination like a good ghost story. But is there more to a spooky tale than thrills and chills? What do our ghosts say about our cultural values? Are we more afraid of who haunts us, or what we’ve done to deserve that haunting? We discuss these questions this week on a very SPIRITED Death in the Afternoon.

Some quick fun facts about this episode:

Or Maybe, it’s a Ghost was originally conceived as a Halloween Episode, since we knew the podcast would be running during Halloween week. It replaced a previous pitch for an episode focusing solely on cemeteries of enslaved people, but we just couldn’t connect all the stories in a way that worked. In the end the subject expanded into what became Or Maybe, it’s a Ghost?

The exchange between Louise and Sarah was put together in the recording studio at the last minute.

Order member Colin Dickey’s book Ghostland was one of our inspirations for this episode. You can read an excerpt here.

Prior to working with The Order, Louise wrote a regular series on the now defunct xoJane called Creepy Corner, where she covered folklore, urban legends, and ghost stories.

We receive a lot of emails every year asking if Caitlin believes in ghosts or if she ever had a “ghostly” experience. We usually refer them to this episode of Ask a Mortician.

Lucky for us all, Louise is back this week to share a bit about her family and…GHOSTS!

You may or may not know this, but my first real job as a writer involved writing a weekly column about ghosts. Ghost stories, folklore, death legends, cemeteries, cultural death traditions – for four years I lived and breathed in that creepy little corner.

When that publication met its demise and Caitlin asked me to come work for her it felt like a natural progression. Once again ghosts were my stepping stone into the conversation about death.

I say “once again” because growing up, ghosts were my gateway to talking about death with my family. In my Chinese American family, talking about the ghosts my great-grandmother supposedly shared a home with led me to asking my mother about who those ghosts were and how they got there.

I’m always amazed that people tend to gloss over the fact that every ghost story is born of death. We are so afraid to talk about death that we just skim over that important detail.

When I asked about my great-grandfather’s ghost, the conversation eventually turned to his death and funeral. My mom told me about the family altar in my great-grandmother’s basement; I learned about the tablets that had our family members’ names inscribed on them on that altar; I learned about how great-grandmother cared for her husband’s body; how his body stayed in his home; how they sat with him; how the monks came to bless him.

I’ve known about my mom’s death plan since I was around six-years-old. When she told me about the angry ghost that my family says skulked around the second floor of my grandmother’s house, we talked about why a ghost might be angry. Then we talked about what would make my mom a happy ghost someday. A lot of being a happy ghost had to do with giving her the death and funeral she wants.

“I’ll come back and haunt you if you don’t do what I tell you!” my mom would joke. I think she was joking. Honestly, if ghosts do exist, I have no doubt my mom will come back and haunt me if I don’t follow her plans to the letter. Who am I kidding? Even if there are no such thing as ghosts, my mom will haunt me out sheer force of will.

I completely understand why some may balk at the inclusion of ghosts when talking about the reality of death, mortality, and death positivity. In the wrong hands, ghosts give us a way to avoid looking the reality of death square in the face. We just jump over the whole “dying part” and suddenly it’s all about disembodied voices and ghosts tapping out answers to your questions at the seance table. They can be a conduit through which we absolve ourselves of cultural responsibility when they take the form of vengeful spirits or troubled entities that simply need to “go into the light”. If ghosts mean immortality, why concern ourselves with mortality?

But for me, ghosts eased me into thinking about death. A good death, with the dead person’s wishes fulfilled would make a “happy ghost”. That’s super simplistic, but those kinds of thoughts were some of Little Louise’s first forays into death positivity. Death was not merely an insignificant stop on the way to the great beyond, it mattered. How we treat the dead mattered.

I had to ask myself the big question: what would make me a happy ghost?

Louise’s ghost book recommendation: Yurei: The Japanese Ghost by Zack Davisson.

This book is a delightful dive into the spirits of Japan. I love how Davisson approaches Japan’s ghost-lore as both a scholar and an eager listener. His book dedication says it all:

To my wonderful wife, Miyuki Davisson. And to OIwa, Otsuyu, and Okiku. Please don’t hurt me.

(Oiwa, Otsuyu, and Okiku are three of Japan’s most famous – and dangerous – ghosts.)

Zack is also an Order contributor! You can read an excerpt from his latest book The Supernatural Cats of Japan, here.

Now, here’s Sarah to talk a bit more about her segment, and another local legend whose origin can be traced back to another forgotten woman (cw: violence, murder):

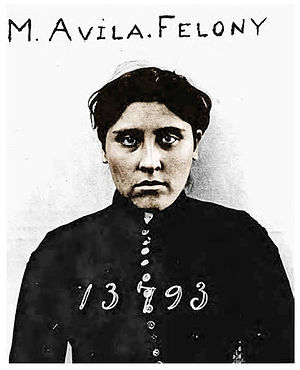

Like Avila and La Llorona, urban legends and ghosts are often tied to real people and events. The thing is, most communities have their own local ghosts and monsters that are an important part of their identity as a community and local history. There’s a great documentary that examines one such story, Cropsey (available to watch on Hulu or Shudder), which allows viewers to accompany a pair of siblings as they unravel a local legend from their childhood in Staten Island, revealing a horrible reality.

When I was a kid, there was one rule for all of us – when the streetlights came on, it was time to come inside. I don’t ever remember anyone defying this rule, not only because we’d probably get the dreaded chancla thrown at us, but because if you were a child out after dark in our neighborhood, “She’d get you” – a woman in white, screeching like an owl and clutching a hammer, roaming the hills of East LA, looking for more pint-sized victims.

Enter real life LA murderess, Clara “Tiger Girl” Phillips, who in 1922 purchased a hammer, lured a friend she was jealous of into a car, and brutally murdered her with it. According to historian Joan Renner, Clara then went home covered in her victim’s blood, and cheerily announced to her husband that she was going to cook him the best dinner he’d ever had.

I’d love to know about your hometown ghosts and monsters – you should totally @ me on Twitter or Instagram @DeathAfternoon

Death in the Afternoon is a podcast written, researched, and developed by Caitlin Doughty, Sarah Chavez, and Louise Hung of The Order of the Good Death.

Caitlin Doughty is a mortician and funeral home owner in Los Angeles, CA. Along with Sarah and Louise she runs The Order of the Good Death and the Good Death Foundation, orgs that spread the death positive gospel around the world through video series like Ask a Mortician, blogs, bestselling books, and now, a gosh darn podcast!

Sarah Chavez is the executive director of The Order of the Good Death. As the child of parents in the entertainment industry, she was raised witnessing choreographed Hollywood deaths on soundstages. Her work has been influenced by her unique life and weaves together the relationship between death and food, feminism, Mexican-American death rituals, and the strange and wondrous history surrounding the culture of death itself.

Louise Hung is a writer, researcher, and community manager for The Order of the Good Death. While she can usually be found hunched over her computer working on video scripts for Ask a Mortician, Louise has also been known to tap out a few words about death in folklore, history, pop culture, and Asian or Asian American communities.

Editor and composer: Dory Bavarsky

Engineering: Paul Tavener

DEATH IN THE AFTERNOON PODCAST – Or Maybe, it’s a ghost?: SEASON 1: EPISODE 7

What happened to the dead of Hiroshima?

November 24, 2018

DEATH IN THE AFTERNOON PODCAST – Embalmed Alive: SEASON 1: EPISODE 6

Each week, on Wednesday you’ll get a new episode of Death in the Afternoon; a podcast about all things mortal. You can listen (and subscribe!) on iTunes or Spotify.

What can I expect from Death in the Afternoon?

Our mission is to educate our audience about death in a unique, relatable, and entertaining way; to further open up conversations about death in a death phobic culture. And sometimes (ok, all the time) let things get delightfully bizarre.

From our podcast you can expect:

The surprisingly heartwarming tale of a woman who just couldn’t say goodbye to her dead family.

Baffling, chilling, and bizarre stories of when people die in a cult.

When embalming goes right, wrong, and WTF.

Plus many more stories plucked from current events, our favorite historical incidents, and death folklore. You can listen to our Season One trailer here.

For each episode of Death in the Afternoon we’ll publish a blog with images, additional reading, watching or listening, and behind the scenes notes about the making of each episode.

Welcome to our sixth episode, Embalmed Alive

Episode description: Embalming. It sounds like the stuff of horror movies: pump a dead body full of chemicals to make it look alive – ALIVE! Whose idea was this? Is there really such a thing as “extreme embalming”? And what about when embalming (allegedly) goes horribly, horribly wrong? We discuss these and other questions on this week’s episode of Death in the Afternoon.

This week our intrepid mortician and researcher pick apart another current event, from 2018, “Russian woman embalmed alive in deadly hospital mistake.”

Indeed. She does.

Caitlin and Louise also discuss another subject we get frequent emails, asks, and comments about at The Order – extreme embalming, posing an embalmed corpse in a “life like” pose. Here’s Louise with a bit more about this segment:

When I was working on the section about “extreme embalming” as Caitlin calls it, I was struck by why Angel Luis Pantojas wanted to be embalmed and posed standing at his funeral.

Most publications give little mention as to why Pantojas wanted to be standing. Honestly, I don’t know all the details. But from what I gather, at six-years-old Pantojas stood at his murdered father’s open casket and essentially said, “This is not how I want people to see me. I want people to see me on my feet when I’m dead.”

It’s a staggering moment for anybody, but especially for a child. Growing up amidst guns and violence in San Juan, Pantojas did not get the gentle exposure to death and dying that so many of us wish for our children. It’s a privilege to approach death on your own terms, not the other way around. At such a tender age Pantojas not only had to confront the reality of death, but he also made a decision as to what he wanted for his death.

At six, Pantojas told his family that’s what he wanted and he maintained those wishes up until is death at age 24. I don’t pretend to know his family, but I wonder how such a declaration was taken from a child? I think about if my young niece told me this. Would I receive it with humor? Gravity? Would this death plan formed in the obstinance and innocence of childhood be binding? Would I hold her wishes dear to me and solemnly promise to adhere to her plan?

Of course, my niece lives in a world where her childhood is sheltered from gunshots and harshness. Her worries are of the chickens in her backyard getting along and what Grammy might give her for Christmas (and Hanukkah).

I’m not sure that’s the world that Pantojas grew up in.

Angel Luis Pantojas died brutally. He was “shot 11 times, twice in the face, and tossed over a bridge in his underwear.” He died an adult with the funeral wishes of a child.

Maybe that’s not fair to say. The way he wanted to be dead evolved, even if the idea was planted in his youth. He told his family he wanted to be on his feet, seen as strong, he didn’t want to leave the world lying down. To their credit they honored this.

I don’t pity Pantojas. My heart aches for a life cut short. I also don’t want to cast a sentimental haze over a society plagued by violence. Pantojas did not die gently and his death plan was not gentle either. It was defiant.

No matter what my personal beliefs are on embalming as a routine practice, I’m happy that Pantojas and his family had the option to pose his body standing, el muerto parao.

Miriam Burbank at her funeral.

Additional reading:

This Family Embalmed Their Loved One to Look Alive At His Funeral

Funeral tradition upended in Puerto Rico

Dead People Get Life-Like Poses at Their Funerals

Extreme embalming is not exactly new, as Sarah tells us in her segment about the Bisga Man:

The Bisga Man is another story I’ve been wanting to tell for a number of years, but the idea that has always captured my interest is the concept that an embalmed body will provide mourners with a final “beautiful memory picture.” Something I hope listeners will take away from this episode is this reminder from Caroline Vuyadinov, that the “memory picture” is not the property of the death care industry:

Memory pictures are those memories we hold dear of our loved one. They are the many memories we have of our loved ones who have died that bring us joy and make us remember just how wonderful they were. No industry can direct the memoires of our loved ones. I think if we all took the time to talk about death, and what we need to do at the time of death, our loved ones would be at the mercy of the “professionals” that present choices that fit their belief system but not ours. In this season, let us make memories of those we love, and take the time to express to those around us what we want as our final wishes.

Death in the Afternoon is a podcast written, researched, and developed by Caitlin Doughty, Sarah Chavez, and Louise Hung of The Order of the Good Death.

Caitlin Doughty is a mortician and funeral home owner in Los Angeles, CA. Along with Sarah and Louise she runs The Order of the Good Death and the Good Death Foundation, orgs that spread the death positive gospel around the world through video series like Ask a Mortician, blogs, bestselling books, and now, a gosh darn podcast!

Sarah Chavez is the executive director of The Order of the Good Death. As the child of parents in the entertainment industry, she was raised witnessing choreographed Hollywood deaths on soundstages. Her work has been influenced by her unique life and weaves together the relationship between death and food, feminism, Mexican-American death rituals, and the strange and wondrous history surrounding the culture of death itself.

Louise Hung is a writer, researcher, and community manager for The Order of the Good Death. While she can usually be found hunched over her computer working on video scripts for Ask a Mortician, Louise has also been known to tap out a few words about death in folklore, history, pop culture, and Asian or Asian American communities.

Guest Writer: Allison C. Meier is a Brooklyn-based writer focused on history and visual culture. Previously, she was a staff writer at Hyperallergic and senior editor at Atlas Obscura. She moonlights as a cemetery tour guide.

Editor and composer: Dory Bavarsky

Engineering: Paul Tavener

DEATH IN THE AFTERNOON PODCAST – Embalmed Alive: SEASON 1: EPISODE 6

November 17, 2018

Overcoming DEATH DENIAL In Your Family

November 15, 2018

DEATH IN THE AFTERNOON PODCAST – It’s ok to not decay: SEASON 1: EPISODE 5

Each week, on Wednesday you’ll get a new episode of Death in the Afternoon; a podcast about all things mortal. You can listen (and subscribe!) on iTunes or Spotify.

What can I expect from Death in the Afternoon?

Our mission is to educate our audience about death in a unique, relatable, and entertaining way; to further open up conversations about death in a death phobic culture. And sometimes (ok, all the time) let things get delightfully bizarre.

From our podcast you can expect:

The surprisingly heartwarming tale of a woman who just couldn’t say goodbye to her dead family.

Baffling, chilling, and bizarre stories of when people die in a cult.

When embalming goes right, wrong, and WTF.

Plus many more stories plucked from current events, our favorite historical incidents, and death folklore. You can listen to our Season One trailer here.

For each episode of Death in the Afternoon we’ll publish a blog with images, additional reading, watching or listening, and behind the scenes notes about the making of each episode.

Welcome to our fifth episode, It’s OK to Not Decay

Episode description: Ah, to die, to decompose, to become one with the earth. Most of us accept this as our fate. But what happens when that whole “decomposition thing” doesn’t go as planned? This week we discuss incorrupt corpses that inspire devotion, grant miracles, and just might help you to become a karate champion.

This isn’t a story about an incorruptible corpse, but it is a story about the corpse of a child that inspired devotion in Louise’s mother’s community when she was growing up. Here’s Louise with the story (tw: child death):

My mom grew up in the Wan Chai neighborhood of Hong Kong. Cutting through the neighborhood was a waterway called a nullah. The nullah guided water down the mountain that looms over Wan Chai; sometimes just a dribble, often times a torrent during typhoon season.

One rainy day (rainy days in Hong Kong can be monstrous) disaster struck. Some children were swimming in a pool high up on the mountainside, when a flash flood swept the smallest child over the edge and down the nullah where he drowned.

His little body came to rest where the nullah passed through the shops and vendors that populated the area. My mother, whose job it was to walk her younger siblings to school, passed the child lying in the nullah – the characters of the neighborhood surrounding him but unwilling to move his body. When my mother came home from school that evening the child, the “Nullah Baby”, was still there.

You see, nobody would move his body without the permission of the monks from a nearby temple, and for some reason they had not come to collect him yet.

The Nullah Baby stayed in the nullah for another whole day. People cried and gathered around him. Some just stared, others laid offerings. But life continued, swirling around the Nullah Baby’s corpse.

Finally, the Nullah Baby was moved and his remains cremated (so my mother says). A little shrine was arranged for him in the neighborhood temple and people from the community came out to pay their respects or just check out the Nullah Baby shrine.

But something interesting happened. The shrine stayed put for some time, my mother says years, and it became something of a pilgrimage site for people in Wan Chai and Hong Kong. People believed that the Nullah Baby would safeguard the lives of those threatened by water.

Wives would ask the Nullah Baby to bring their husbands safely back from sea. People would ask the Nullah Baby to protect their homes and children from the flooding and typhoons that plague Hong Kong. Mothers would even stop at the temple to ask the Nullah Baby to protect their children if they went swimming at the beach that day.

And most of all, the Nullah Baby protected other children from the nullah.

Memory of the Nullah Baby is mostly gone. The nullah is still there (though it doesn’t wind through the neighborhood as it once did), as is the temple, and a few plaques commemorating the accidents that happened around the nullah in the early and mid 20th century. I’ve found one mention of a drowned child.

But my mother remembers. She remembers the Nullah Baby in the water; she remembers being afraid; she remembers his shrine.

And she remembers the years where the Nullah Baby watched over Wan Chai.

Miguelito, discussed in the first segment of this episode, with some visitors.

Above is a post mortem photograph of Paramahansa Yogananda, from Sarah’s segment, whose corpse was embalmed and cared for by Forest Lawn. Employees at the mortuary claimed that Yogananda’s corpse remained “in a phenomenal state of immutability.” This “miracle” (spoiler alert: it wasn’t), was cited at length in a letter from Harry T. Rowe, the acting Mortuary Director of Forest Lawn Memorial-Park Association at the time, which you can read here.

Yogananda welcoming visitors to his “Spiritual White House” in Mount Washington, CA.

Yoganada’s Self Realization Fellowship in Mount Washington still exists, but if you happen to be in or around Los Angeles, a trip to the SRF in Pacific Palisades just off the Pacific Coast Highway, is worth your time. The location features the Lake Shrine and is one of the most beautiful spots in the city.

Of course you can also visit Yogananda at Forest Lawn. He is interred in the Sanctuary of Golden Slumber in the Great Mausoleum. Followers often visit and meditate or do yoga in front of his crypt.

Illustration by Landis Blair, for Caitlin Doughty’s book, From Here to Eternity.

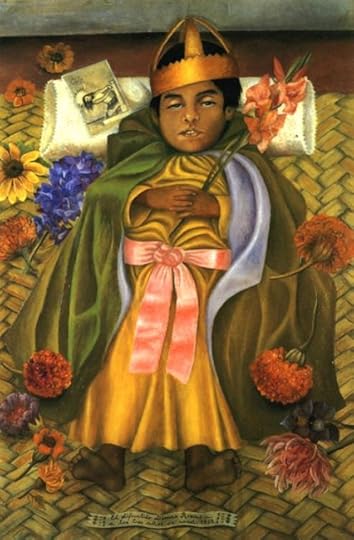

Hi again, Sarah here. This episode touches on several of my favorite subjects, Los Angeles and Forest Lawn history, corpse science, and angelitos. If you’ve read Caitlin’s book, From Here to Eternity (ahem, now available in paperback), you’ll already know how meaningful the of the beliefs and rituals surrounding angelitos have been for me.

One of the primary rituals that supports the mythos surrounding angelitos, is the dressing of the corpse. At death, the child is clothed in the guise of a carefully chosen religious figure; as they are believed to acquire the characteristics of the holy figure whose costume they wear. The appointed Godmother of the child was typically responsible for bathing the corpse and either making or providing the saint costume according to the parents’ preferences. Part of the reason this task is taken on by someone other than the mother is out of a desire to help her come to terms with and fully realize and accept the child’s transformation so, when she sees her child again, the visual representation of the child’s new role, now no longer a mortal, but a heavenly being, is realized.

These theatrical displays have given rise to a particular genre of art, both in painting and in photography. Angelito post mortem portraits serve as vignettes of a theatrical drama that once took place through the enactment of various rituals, reinforcing the belief of the transformation of the child into a heavenly being.

These post mortem photographs and portraits of angelitos are quite rare, butI am lucky enough the have a small collection of them myself, and they are by far my most beloved and cherished possessions. They are very different then the Victorian era postmortem portraits you are likely familiar with which often depict the subject as peacefully sleeping. In contrast, many of the angelito portraits are and theatrical and dramatic, featuring angelitos who are costumed, and often posed upright and depicted with props. I even have one with an infant holding the scales of justice in one hand and a small sword in the other.

Most of the portraits in my collection came from a dear friend who considered them to be like his “children,” and wanted to make sure they were passed on to someone who would care for them as much as he did. When I am at the end of my life, they will be passed on to another person, who will continue to care for them with love and reverence.

“The Deceased Dimas Rosas at 3 Years Old” by Frida Kahlo, 1937

Here is one example of a portrait painted by Frida Kahlo. The child was the Godson of her husband, Diego Rivera.

Death in the Afternoon is a podcast written, researched, and developed by Caitlin Doughty, Sarah Chavez, and Louise Hung of The Order of the Good Death.

Caitlin Doughty is a mortician and funeral home owner in Los Angeles, CA. Along with Sarah and Louise she runs The Order of the Good Death and the Good Death Foundation, orgs that spread the death positive gospel around the world through video series like Ask a Mortician, blogs, bestselling books, and now, a gosh darn podcast!

Sarah Chavez is the executive director of The Order of the Good Death. As the child of parents in the entertainment industry, she was raised witnessing choreographed Hollywood deaths on soundstages. Her work has been influenced by her unique life and weaves together the relationship between death and food, feminism, Mexican-American death rituals, and the strange and wondrous history surrounding the culture of death itself.

Louise Hung is a writer, researcher, and community manager for The Order of the Good Death. While she can usually be found hunched over her computer working on video scripts for Ask a Mortician, Louise has also been known to tap out a few words about death in folklore, history, pop culture, and Asian or Asian American communities.

Editor and composer: Dory Bavarsky

Engineering: Paul Tavener

DEATH IN THE AFTERNOON PODCAST – It’s ok to not decay: SEASON 1: EPISODE 5

November 13, 2018

Organ Donation for Home Funeral Bodies?

Caitlin Doughty's Blog

- Caitlin Doughty's profile

- 8406 followers