Caitlin Doughty's Blog, page 13

November 21, 2019

Death & Disney: Walt’s Morbid Obsessions

October 21, 2019

Iconic Corpse: The Romanov Family

Known to God: Mourning an Unnamed Child

I live in Edinburgh, in the northern part of the city known as Leith. Barely a minute’s walk from my home is one of the area’s largest public parks; Leith Links. Believed by local legend to be the birthplace of golf, the Links is a much-needed swathe of green in what is still a very industrial section of the city. Joggers and cyclists criss-cross the grass, shouts rise up from amateur football matches. Children race from nearby schools to get to the climbing frames before their friends. In summer the local cricket team add a slight touch of the English countryside to this Scottish park. In winter the head-torches of keep-fit groups bob eerily in the gloom. Smoke from the next-door allotments drift lazily alongside buzzing drones and swooping kites.

Every facet of local life finds a use for the Links, every day of the year. Yet where life makes it home, so too does death.

One day in 2013, July 28th to be exact, a dog-walker made a gruesome discovery. Strolling from the park proper onto the paths which are all that remain of the area’s Victorian narrow-gauge railway he found, wrapped in an elephant-print blanket, the body of a baby boy. I remember being surprised, as I walked my own dog in the same area, to see it cordoned off by police.

It was the next day when details of the discovery started to appear in the local news.

The baby was, as Detective Chief Inspector David McLaren announced at a later press conference, “closer to being a newborn than a toddler”. Later reports would put the age at no older than six weeks. Some news articles mentioned reports that “the body had been mutilated, possibly by animals”. Although never confirmed this is plausible, both foxes and badgers live in the area, and this may explain why, despite a major police investigation, the baby was never identified and his family never found.

The baby was, as Detective Chief Inspector David McLaren announced at a later press conference, “closer to being a newborn than a toddler”. Later reports would put the age at no older than six weeks. Some news articles mentioned reports that “the body had been mutilated, possibly by animals”. Although never confirmed this is plausible, both foxes and badgers live in the area, and this may explain why, despite a major police investigation, the baby was never identified and his family never found.

Not such a cheerful tale. Not such a positive story.

At least not at the start.

Two years after the body had been found, with no family forthcoming, it became clear that something had to be done with the child’s body. Police Scotland themselves organised a funeral service and, due to worries that it could be a sparse affair, an announcement was placed in the Scotsman newspaper. It read:

“Unknown Little Baby Boy (Seafield, Edinburgh). With deep sadness, the little baby boy who was found wrapped in his blanket on the walkway/cycle path at Restalrig, Seafield, Edinburgh, will be laid to rest at Seafield Cemetery, on Friday, May 1, 2015, at 10am, to which all will be warmly invited to come along and pay their final respects to this little baby boy.”

It was the best they could do.

It was enough.

On the day itself, sunny but cold as the Scottish spring often is, over two hundred people congregated in the cemetery to watch Cooperative Society funeral director Ian Thompson lay the child to rest. The coffin, so small that Mr Thompson could hold it in his arms, held a plaque marked simply “Known to God. Precious little angel”. The Guardian newspaper described the funeral attendees as a disparate group “gathered from across Edinburgh and eastern Scotland. There were bikers from the Royal British Legion Scotland, a representative of Leith’s Sikh community, several of the city’s politicians from rival parties putting the election campaign aside, and mothers who themselves had lost children”. Many wept, some simply stood in silent thought. Others no doubt glanced over to the shrubbery and low trees that separate the cemetery grounds from the path where the little boy’s body had been found before leaving their tribute of flowers or toys beside the grave. One note, handwritten, read “twinkle twinkle little star, how we wonder who you are…”.

What led to this powerful show of local solidarity? What caused people – not just from Leith but from the rest of Edinburgh and further afield in Scotland – to give up their time and mourn a stranger? The words of Reverend Erica Wishart, who led the service, give some insight: “We are here to say goodbye to this wee one, with the dignity and respect he deserved. We are here to mourn the life that could have been”. She continued by admitting that there were “so many things we don’t know, so many things we don’t understand” but ended with the hope that the mourners “found some peace and comfort here”.

These words reveal a fact that rings true in taciturn Scotland, that we often find hard to admit; funerals do not comfort the dead, they comfort the living. Many attendees on that crisp May morning would have been thinking of their own losses, past or potential. “I know what it’s like to lose a child,” Claire Phillips told reporters while Colin Macnab of the Royal British Legion Scotland bikers admitted that “we all feel compassion; it could be [one of us] one day”. By having no family, no history that anonymous child became a cipher through which each individual’s own grief could be expressed.

Yet this raises an interesting question; with such an extraordinary expression of community compassion appearing for the baby’s death – “[S]omething like this touches everyone’s hearts. This is a great community. Leith is a great community”, said Reverend Wishart and her words were echoed by another mourner who said “[i]t’s very moving to think that there are so many people here today just to give this baby some love” – where was this support before the baby’s death? Where was the love for a mother who felt she had no choice but to leave her baby to the elements, no doubt aware that it would die? Is it simply that we are too busy to care or is it more that, as Scottish writer Helen McLory put it in her short story Bound To Be, “community means all ignoring the same cruelty”?

It is very much the case that we, as communities, often prefer to look back on death as something inevitable to be mourned rather than confront the responsibilities we have as a community to prevent death, at least when it is preventable. In fact, is it really death that we recoil from or is it rather the process of dying?

It’s more than unfair to ascribe any blame to the mourners in attendance on that May morning, I would have to blame myself just as much, but we should always remember that death is overwhelmingly not something that appears out of nowhere. Death is the final symptom of a process of ailments, many of them societal as much as physical, and, in this increasingly gentrified but still very much working class part of Edinburgh, is it easier the accept the delimited grief of death than the ongoing burden of knowing that some of our neighbours live in poverty and despair? Death happens and then death leaves, a very literal memento mori that can be a much-needed jolt to those who remain, but the process of dying lingers, sometimes over years, and exposes all the weaknesses we try our best not to accept.

Today, in 2019, there are still flowers and toys around that little grave. There is still compassion and thoughtfulness in the world. Yet if that compassion didn’t wait for death to reveal itself but was offered freely when needed then maybe those flowers and toys could be celebrating a birthday and not commiserating a death.

Daniel Pietersen is an author of weird fiction and of critical non-fiction that investigates the nature of horror. He is a regular contributor to Dead Reckonings, the in-house journal of Hippocampus Press, and Sublime Horror. His fiction has been published in The Audient Void, Mycelia and Aether & Ichor. Daniel lives in Edinburgh, Scotland, with his wife and dog and can be found on Twitter as @pietersender.

October 13, 2019

Your Funeral Shouldn’t Cost $15,000!

September 27, 2019

Every Word of the Sepulcher – How the Seventeenth Century Teaches Us to Die

Among the pilfered treasures of the British Museum – the black heft of the Rosetta Stone, the gray bulk of a monolithic Easter Island head, the cool whiteness of the Elgin Marbles – there are a few galleries with artifacts dug from closer ground. In the seventeenth-century, English antiquarians curious about sites like Stonehenge began to sift through their own soil. Among those collections, there are a number of funerary urns pulled in 1658 from a sandy field near Walshingam Norfolk.

Within a typical urn there might be “two pounds of bones, distinguishable in skulls, ribs, jaws, thigh-bones, and teeth, with fresh impressions of their combustion,” as the discoverer wrote. Plaintive in their simplicity, the urns are only a foot tall, simple designs pinched into the clay by hand or stylus before some ancient kiln baked them to blackness. The urns appear ancient, primitive, archaic, primal. Cross-hatched circles line the circumference and diagonal slashes frame dots pressed like birthmarks on flesh. In their mournful minimalism there is stark beauty, the type of unadornment that makes them seem as if relics from a quiet, timeless place.

Their discoverer was a curious, erudite, humane physician and essayist named Thomas Browne. Archeology being in its infancy, Browne misidentified the urns as Roman, with later specialists dating them as from the Anglo-Saxon period. Regardless of their provenance, Browne sensed intimations of eternity, missives from that country of death. Though not uncheerful, Browne was still a thinker predisposed to melancholia, an affliction that had a bit of the fashionable about it. Considering his urns, Browne argued that how “Time which antiquates Antiquities, and hath an art to make dust of all things” was a reminder that the “long habit of living indisposeth us to dying.”

Both quotations come from Browne’s Hydiotaphia, or Urn Burial (the cumbersome Latinate word is just a translation of the English phrase next to it). Much more than simply an account of archeological curiosity, Urn Burial is arguably one of the most thoughtful, moving, and wondrous reflections on mortality written in the English language; a book all the more wondrous not in spite of its melancholia, but because of it. Browne writes that “man is a Noble Animal, spending in ashes, and pompous in the grave, solemnizing Nativities and Deaths with equal luster, nor omitting Ceremonies of Bravery, in the infamy of his nature.” He is a witness of that dusk when the certainties of faith were just beginning their sunset, but an idiom of the sacred still held a charged potential.

By Jan van Kessel.

By all accounts a pious (if liberal) Anglican, Browne is conversant with doubts; his curiosity countenances a skepticism to what death means, for “Darkness and light divide the course of time, and oblivion shares with memory, a great part even of our living beings.” Browne is the great notary of gloaming, of the intermixed darkness and light, whether it be the transitionary period of his century or the caste of his own mind which could sometimes relish the thought of eternal life and sometimes despair at the possibility of extinction, while uncovering a way to live between those two extremes as surely as an Anglo-Saxon urn can be pulled from the earth.

Two centuries later and Ralph Waldo Emerson would say of Urn Burial that it “smells in every word of the sepulcher” – this wasn’t necessarily an insult. Browne’s prose has often been counted a rare delight, including advocates from Edgar Allan Poe and Herman Melville (who called him a “crack’d archangel”), to Virginia Wolf and Jorge Luis Borges. His writing isn’t always easy; no less an enthusiast than the eighteenth-century lexicographer Dr. Johnson described Browne’s style as a “tissue of many languages; a mixture of heterogeneous words, brought together from distant regions… and drawn by violence into the service of another.”

Yet there is a necessity to this style in confronting the grave. The seventeenth-century, fractured by religious strife and doubts incubated by new science and philosophy, could not simply prescribe the palliatives of religious certainty when it came to the universal fear of death. The difficulty, though it must also be said exquisite beauty, of Browne’s serpentine, unwieldy, Latinate, Mandarin prose is that the doctor was attempting to think beyond simple answers to his questions, to imagine how we face the rich, black soil of a Norfolk burial without assurance of greater meaning.

Browne was no atheist, and yet during his age the old truths seemed less and less obvious. Mortality’s literary canon goes back deep into antiquity, but Urn Burial gives voice to an anxiety of not just damnation, but extinction; acknowledging the fear of uncertainty and in turn generating something beautiful out of that. When it comes to meditating on our deaths, such prose doesn’t necessarily approach what lay beyond (for that’s veiled from us), but rather simply conveys a sense of the numinous, the sacred, and the transcendent as it exists in every pregnant second. The physician’s tone is not one of despair, for “Life is a pure flame, and we live by an invisible Sun within us.”

Such writing was composed just as the embers of absolute faith sunk below a darkening horizon, as when Donne observed that “new philosophy calls all in doubt.” For the neophyte looking to supplement their reading on mortality, there is a veritable syllabus that approaches final things in a manner like Browne. Of a similar caste of mind is Robert Burton, author of 1621’s massive Anatomy of Melancholy, which remains the longest psychological text ever written in English. The seventeenth-century may have been an age of melancholy, but it was also an age of curiosity and delight, when explorers would assemble exhibits called “Wonder Cabinets,” filled with beautiful shells, gems, and artifacts (such as ancient urns). In some ways Burton’s approach to both his subject, and to death, was to aestheticize them, to examine even death with delight, so that “All my joys to this are folly/Naught so sweet as melancholy.”

By Heinrich Hoerle.

Then there is the divine poet who went from being the Catholic rake, Jack, to the Anglican dean Dr. Donne, without ever altering the substance of his commitments, and whose Holy Sonnets are the greatest poetic consideration of death in literary history. He of the arresting detail, the so-called “metaphysical conceit,” from the image of graverobbers exhuming a corpse to discover “A bracelet of bright hair about the bone” in memory of the deceased’s beloved, to that of a diseased body examined by doctors as if they were “Cosmographers, and their map, who lie/Flat on this bed.” In 1624’s Devotions Upon Emergent Occasions Donne reflects on what it’s like to be a patient with (what he believed to be) a terminal illness, writing with frankness that “I know not what fear is, nor I know not what it is that I fear now; I fear not the hastening of my death, and yet I do fear the increase of the disease” – an honesty which contemporary palliative care-givers should keep in mind.

Donne was the sort of man who had a lithograph of himself in his death-shroud made and hung opposite his bed, so that upon wakening he could remember that his days were limited. It was in that shroud that he’d preach his most celebrated sermon in 1631, given shortly before he would die, where he acknowledged that death is something which perennially stalks us, “the manifold deaths of this world.” What’s so powerful about Donne’s approach is this this awareness of mortality permeates our existence from womb to tomb, so that “Our critical day is not the very day of our death, but the whole course of our life.”

Browne, Burton, and Donne were all united in a certain humane sensibility, something often called latitudinarianism (fantastic word), which broached a high degree of tolerance when it came to religious certainties. Anxiety has always surrounded death, but in the seventeenth-century there was perhaps a new fear – of Nothingness. These writers deployed Ars Moriendi and Memento mori to approach death in a century when consoling truths were drifting away, like smoke from a funeral pyre. However, the greatest consideration of mortality from the century, perhaps any century, wrestled with those uncertainties, and spun beauty from our doubts and fears.

Try and remove yourself from the clichés of Shakespeare’s 1602 Hamlet: “To be, or not to be, that is the question.” All of that dramatic baggage, black turtle-neck clad Hamlet holding Yorick’s skull, Laurence Olivier enunciating every syllable in his ridiculous trans-Atlantic accent. Shakespeare’s greatest hits – “slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,” “sea of trouble,” “mortal coil.” So famous are these lines, so estimably quotable, that of no fault of Shakespeare’s they’ve almost achieved self-parody. I once saw a production in Glasgow where the director moved the soliloquy to the prologue, just to get it out of the way.

By Frans Hals.

But when approached with fresh eyes, what the passage presents is nothing less than a subversive Ars moriendi for a secular age, where even after God has departed, a vocabulary of the sacred still exists. We have the consideration of death as a nothingness, “To sleep, perchance to dream… For in that sleep of death what dreams may come.” A bluntness to Hamlet’s skepticism, for neither heaven nor hell are promised, but rather the uncertainty concerning the “dread of something after death,” this “undiscovered country from whose bourn/No traveler returns, [which] puzzles the will” (note the personal skepticism in that final word’s pun).

Hamlet’s contemplations are a strange type of manual, for Shakespeare wrote long after Renaissance and Reformation had eroded antique certainties. That’s what Shakespeare presents: the wisdom that even in uncertainty, death demands our attention; even with skepticism, mortality requires our contemplation. Ironically, Shakespeare’s greatest argument here isn’t anything he actually says, rather it’s in how he says it. By using a sacred language, even as he meditates upon the enormity of all which we shall never know, he demonstrates that there is still something of the holy in our poetry, regardless of what country (or none) we’re headed towards in the hereafter.

Ed Simon is a staffwriter for The Millions and an editor for Berfrois. His book “Furnace of this World; or, 36 Observations about Goodness” was published by Zero Books this summer. He can be followed on Twitter @WithEdSimon.

If you enjoyed this piece, please consider supporting our work. Your contribution goes directly toward running The Order, including resources, research, paying our writers and staff, creating videos, podcasts, events and funding more frequent content. We’d love to keep pushing the funerary envelope in 2019. Visit our Support Us page, for a variety of easy ways to contribute, or become a patron on Patreon for exclusive content and rewards.

Every Word of the Sepulcher – How the Seventeenth Century Teaches Us to Die

September 18, 2019

Kid’s Tea Party at the Mortuary

September 14, 2019

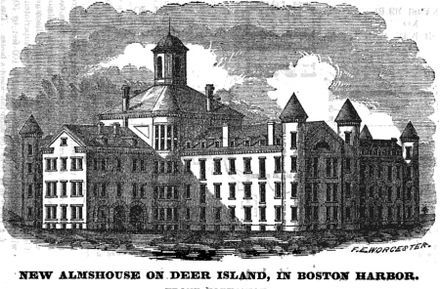

The Hungry Spirits of Deer Island

The spring of 1847 brought stormier skies than usual to Ireland. Hordes of desperate people filled ships said to be tight as coffins. It was a final attempt to outrun starvation at the hands of a bigoted government. They would never see Ireland again, but they might survive…

Illustration of a famine-era “coffin ship” carrying passengers. Via Illustrated London News/Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

In Boston, MA, USA, citizens saw only threats to their mortality. The Coffin Ships emptied their bodies onto Long Wharf — some did not move, others ambled into the nearest shelters. They were gaunt, filthy, covered in sores, burning, contagious —the walking dead.

Faced with this tangible vision of death, Boston’s ruling class doubled down on long held prejudices against the Irish. A Protestant-leaning bias against Irish Catholics became fear of a Holy Roman takeover. A letter to City Hall predicted, “…we shall be driven from our homes by the Lazy, Ungrateful, Lying and Thieving population of old Ireland.” (sic)

But the paranoia on Beacon Hill was not some communal madness. The reaction from Boston’s upper class is defined by psychologists as Terror Management Theory (TMT). Faced with an assumed threat, the brain associates familiarity with safety. It’s the same instinct that causes a fear of strangers. But this psychological defense can also lead to denial of evidence. It can even influence politics.

With one panicked vote, city councilmen designated Deer Island, five miles into Boston Harbor, as the “… suitable and proper place to attend to all the nuisance and sickness accompanying navigation…” It was a reactionary decision that ultimately cost hundreds of lives and robbed thousands more of their humanity.

With one panicked vote, city councilmen designated Deer Island, five miles into Boston Harbor, as the “… suitable and proper place to attend to all the nuisance and sickness accompanying navigation…” It was a reactionary decision that ultimately cost hundreds of lives and robbed thousands more of their humanity.

On Deer Island, a building was hastily erected and a single doctor was designated to screen incoming ships. By summer, the Deer Island Hospital was quarantining 400 new patients per week, most of them young, at 14 to 20 years old. The ills they suffered; typhus, scurvy, even the high birth rate, were symptoms of starvation and poverty. The immigrant mortality rate could have been drastically impacted by expansion of charitable services on the mainland. Yet Bostonians marveled, as if the pain were self-inflicted. Councilman Lemuel Shattuck declared, “…they seem literally born to die.” Every possible diagnosis was used to keep a person on the island. Records described the refugees as mostly suffering “fever,” a symptom too general to justify quarantine, let alone internment.

For three years, thousands of Irish refugees were confined to Deer Island for indefinite sentences. One doctor was given the impossible task of managing them all. The single room filled with cots end to end stank with diarrhea. Cramped and communicable, Deer Island would claim 800 to 1,200 deaths. They survived the brutal Atlantic crossing, then succumbed to fate within clear sight of freedom. A last, their bodies were dumped in anonymous mass graves.

Two additional buildings were constructed on Deer Island in 1850. These served as the foundations of an almshouse and a prison that would operate for another two decades. The use of Deer Island morphed from internment for the Irish, to a vague separation of any poor and unworthy from the rest of the city. Whether out of trauma of the victims, or guilt of the perpetrators, Deer Island Hospital fell out of public awareness.

In 1990 construction began at Deer Island for an innovative new water treatment facility. Work came to halt, however, when backhoes unearthed a cache of human remains. Expecting the remains to be Native American, city coroners were shocked when DNA testing identified the bones as Irish. The archival work began to exhume the memory of the Deer Island Hospital.

Photo by H. Louise Messinger.

Finally, on May 25, 2019, a 16 foot Celtic cross of Irish granite was dedicated to those forgotten souls. Mayor Marty Walsh and other officials spoke to over 600 members of the Boston Irish Community. The monument serves not solely as a memorial, but as a warning.

Photo by H. Louise Messinger.

Our TMT (Terror Management Theory) response is both a feature and a flaw of human evolution. The fear of death kept our distant ancestors safe when resources were limited to hunting and gathering, but today it disguises unarmed black men as aggressors, or slanders those without the language to defend themselves. Confronting the fear of death frees the mind to be critically aware of facts. The age and statistics of the Deer Island refugees mirror those of refugees around the world today. Most are young people who have braved the most dangerous natural conditions to escape the most dangerous man made conditions; war, famine, persecution. Anti-immigration arguments invoke a TMT response with unfounded images of shortage and violence. Narrow understanding leads to policies that serve to punish those who suffer simply for having suffered. Fear does not wait for evidence.

This fear-based status quo often results in internment of thousands of displaced people, unable to move forward or back. Bigoted policies, oftentimes purposefully cruel, rip families apart and cause permanent psychological damage. Overcrowding, unhealthy rations, draconian deprivation mental and physical stimulus are the standards of detainment. For the first time in over a century, refugee children have died in US custody.

The spirits of Deer Island tell the truth of all refugees. They had been given one choice in Ireland: leave, and maybe live — or stay and die. When a person walks 1,700 miles, or sails into dangerous waters, it’s because they are faced with this same choice: leave, and maybe live — or stay and die. The rest of us have another choice. We can choose to question the sources of fear. We can choose to help those in need.

H. Louise Messinger is a journalist based in Boston, Massachusetts. She writes most about history, urbanology, and archaeology. Follow her on Twitter @HLouiseMG

If you enjoyed this piece, please consider supporting our work. Your contribution goes directly toward running The Order, including resources, research, paying our writers and staff, creating videos, podcasts, events and funding more frequent content. We’d love to keep pushing the funerary envelope in 2019. Visit our Support Us page, for a variety of easy ways to contribute, or become a patron on Patreon for exclusive content and rewards.

August 22, 2019

The Collective For Radical Death Studies

What is the Collective for Radical Death Studies?

The Collective for Radical Death Studies, or CRDS for short, is a collective of death scholars, students of death studies, funeral directors, skilled death workers, trained death practitioners, activists who all see death work as social justice work, anti-racism work and work that must include the death/dying experiences of queer folx, black and brown people as well as women, immigrants and all whose death norms and last rites rituals have been othered. CRDS is an international professional organization that produces and disseminates scholarship by and about death scholars and students and death practitioners of color and from marginalized communities. In this way CRDS serves as a source for thinking more critical about the ways in which people of color and those from marginalized communities die, grieve, are buried and are remembered. As an organization, CRDS then a) pushes for death to be understood from heterogenous cultural norms that simultaneously calls attention to the traditional hyper Western focus and b) calls for an interrogation for how societal inequalities shape death and dying.

Why is the work of CRDS necessary?

CRDS is necessary because death is part of every human’s life, yet, in how death is generally understood, discussed, researched and written about, it is disproportionately white and or and/centering on Eurocentric norms. Case in point, those controlling the conversation seem to be unaware that unarmed black people murdered by the police, Mexican immigrants dying seeking asylum in the US or the fact that a trans woman will most likely have last rites performed that are incongruent with her last wishes are all issues that too should be central to death studies.

“Decolonize Your Syllabus” Poster by Yvette DeChavez. Image: Yvette DeChavez.

What does it mean to decolonize death?

When CRDS says that as an international professional organization our mission centers on decolonizing Death Studies, we unequivocally mean to decenter whiteness/Eurocentricism from Death Studies. Within the field of Death Studies one of the prevailing ideas is that Western society is afraid of death which is supported by the normalization of hospice care and even the norm of hospitals and funeral directors starting in the early 20thcentury, i.e. death left the home and normal process of human life. Well, this is a very American white way to view death when you understand that, for instance, under Jim Crow segregation African Americans were legally barred from hospitals or that European colonialism seriously disrupted the Native Americans deathways and not a fear of death. So, it is this type of “American Way of Death” that must be understood as a function of whiteness (i.e. exclusionary) and so must be interrogated with a gender, race, class, sexuality, religion, international lens. Within the CRDS blog entitled “Decolonizing Death Studies” is a longer definition outlined by CRDS president, Dr. Kami Fletcher.

What are some of the different ways CRDS will be implementing their mission?

The creation of our Radical Death Studies Canon goes straight to the heart of implementing the CRDS mission. This literature canon lists scholarship that centers the ways of dying, deathwork and grieving on people of color and marginalized communities. This scholarship, that is not just books, but films, and even websites so to strongly encourage people to think about how dying, burial and grieving have all been shaped and deeply impacted by systems of power and oppression. In the near future, we seek to have virtual educational trainings/classes that will directly focus on decolonizing death and radicalizing death practices. We are currently planning educational tours and a conference where we hope to take participants to experience Dia De Muertos for experiential learning as it relates to decolonizing death. The conference will be a platform to showcase the work of those decolonizing and radicalizing death so to learn and network.

Other than the Radical Death Studies Canon, we are excited to facilitate a Twitter book-club that kicks off in September called #RadDeathReads. All are invited so please check out our website, Twitter and IG for more details.

Image from the Radical Death Studies Canon, on the CDRS website.

How can death scholars, activists, practitioners, and others work toward decolonizing their practices?

As a white person, if you want to decolonize your practices and understanding of death, first, become willing to be uncomfortable in your un-learning, and listen to those whose practices have been marginalized. Second, understand that you personally are not under attack with efforts to decolonize and radicalize death, but that the privilege from which you unconsciously benefit from is being challenged and laid bare. Third, don’t assume that your good intentions are enough. The harm of white supremacy doesn’t only proliferate through harmful intentions. Looking and admitting all this is an important step because racialized white persons and even those reared in a vastly white environment must understand that these blind spots don’t necessarily reflect your character, but social/cultural indoctrination.

Having said that, it’s important to also note that – whether at the center or on the margins – we have absorbed white supremacist values that need to be extorted, they just express themselves differently, depending on your origins. Belonging to a marginalized group doesn’t automatically mean you have the capacity to easily sympathize with another oppressed group, either. Homophobia can be rampant in black communities. Non-disabled and neuro-typical people have to work heavily on their ableism.

Lastly, understanding that the work of decolonizing death is also the work of activism, then to be successful you cannot shy away in acknowledging, and remedying, the violence and bad deaths that haunt the Black, Brown and Indigenous/Native, and LGBTQIA+ communities.

The work will be messy, at times, because it is the work of the bones, of truth, healing, and justice. But you cannot develop nuance without wading through the mess. We have come to a point in our culture in which we would greatly benefit from developing greater discernment and nuanced perceptions of the world around us. Decolonizing death can be just the vehicle.

How can people support the work of CRDS or get involved?

Please go to our website and join our mailing list to receive updates on all CRDS happenings, from the blog to the book club and everything in between. You can also follow us on Twitter and IG and help spread the word about our existence. We appreciate all your #RTs and likes.

As a professional organization that is deeply rooted in educating, we welcome all financial donations that will help us offset our operating costs and expansion of our educational programs. Nothing is too small.

Partnering with us is also a great way to support CRDS. If you are in the health care or death industry or are at the receiving end of these industries and want to work towards decolonizing and radicalizing death, then contact us about partnering. We want to connect with nurses, doctors, doulas, patients, morticians, funeral-home owners, care-takers, activists, artists, the living, the dying and the dead. Let’s support each other by creatinga network of solidarity, support, and sharing.

We are also looking for collaborators who will help expand our mission of decolonizing and radicalizing death through sharing their professional experience and research: indigenous, native, queer, disability researchers and advocates. We want to hear people’s suggestions, want to understand, what are the needs and what are the obstacles. We hope that people will submit blogs or suggestions for our canon that will support our mission. You can find more about our submission criteria on our website.

CRDS Website | CRDS on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook |

Dr. Kami Fletcher, CRDS President, is an Associate professor of American & African American History at Albright College, and contributor to The Order. Dr. Fletcher teaches “African American Deathways and Deathwork” which examines African American norms and ideas surrounding death. Follow her on Twitter.

Dr. Tamara Waraschinski, CDRS Director of Communications, received her PhD in Sociology from the University of Adelaide. She became a social theorist and death scholar, particularly interested in how capitalism corrodes our ability to accept that we are mortal beings.

CRDS logo designed by AJ Hawkins. Read mote about her work here.

Get your own “Decolonize Your Syllabus” poster by Yvette DeChavez here.

The Order of the Good Death is an official partner of CRDS.

If you enjoyed this piece, please consider supporting our work. Your contribution goes directly toward running The Order, including resources, research, paying our writers and staff, creating videos, podcasts, events and funding more frequent content. We’d love to keep pushing the funerary envelope in 2019. Visit our Support Us page, for a variety of easy ways to contribute, or become a patron on Patreon for exclusive content and rewards.

July 25, 2019

Victorian Murder Collectibles and Our Enduring Fascination With True Crime

True crime may seem to be having a moment right now, but illicit tales pulled from real life have long been at the forefront of popular culture. While today’s true crime fans might binge-watch a streaming serial killer docu-series, or go deep into the rabbit holes of Murderpedia, aficionados of previous centuries collected figurines of notorious criminals and bought pamphlets recounting the ghastly details of the latest villainy.

A Staffordshire collectible figurine depicting the death of Lt. Hugh Munro. Photo by Myrna Schkolne 2013.

Staffordshire figures were all the rage in 19th-century England, where the brightly colored ceramic sculptures — recently made affordable by advances in mass production — regularly depicted contemporary celebrities. Queen Victoria riding a horse or Florence Nightingale tending to a wounded soldier could sit alongside miniatures of the singer Jenny Lind or Lady Franklin, wife of the leader of the doomed Franklin Expedition. Then there were the murderers.

Photo by Nick Williams.

An 1856 ceramic of William Palmer, aka “The Prince of Poisoners,” was fabricated the same year he was hanged in front of a crowd of 30,000; 1859 ceramics of Marie and Frederick George Manning were issued the year they were executed for murdering Marie’s lover Patrick O’Connor and burying him under the kitchen floor. Marie was portrayed dressed in a bonnet, holding a handkerchief; the sole indication of her identity was her name in gilt script on the earthenware object’s base. Often these crime-themed figures were “flatback,” meaning the reverse was flat, so they were cheaper to make and meant to be placed on a mantelpiece among other curios. Aside from rare exceptions — like an 1866 group showing Thoman Smith Junior and William Collier engaged in mortal combat — there was nothing overtly violent in their designs.

As Rosalind Crone writes in Violent Victorians: Popular entertainment in nineteenth-century London, “the new preoccupation with narratives of extreme interpersonal violence that emerged around 1820 ensured that murderers predominated within the criminal genre and meant that there were men and women eager to purchase them for display within their homes.”

Staffordshire factories were not the only ones manufacturing Victorian crime knickknacks. The 1899 Catalogue of a Collection of Pottery and Porcelain Illustrating Popular British History from the Victoria and Albert Museum has an entire section on crime, including a creamware mug with a portrait of murderer John Thurtell and another with George Barrington, the “Gentleman Pickpocket.” Yet the Staffordshire factories were particularly prolific in producing ceramics at exactly the moment when public obsession with a crime was at its height. For instance, multiple variations exist of the sites and figures related to murderer James Blomfield Rush, indicating how these factories were rushing to meet demand.

Via christies.com

In 1848, Rush killed his landlord Isaac Jermy and Jermy’s son, with Staffordshire creating not just a figure of Rush with his hand on a podium and a document in the other (perhaps referring to his disastrous self-defense at his trial), but a whole diorama of the crime. This included models of Rush’s home, Potash Farm; the murder site, Stanfield Hall; and Norwich Castle, the location of Rush’s hanging in front of thousands of onlookers. There had been a similar treatment for the 1827 “Red Barn Murder,” in which farmer William Corder shot Maria Marten, who he’d asked to meet at the barn ahead of their planned marriage. The 1828 Staffordshire models showed Corder and Marten together in a pose that could be mistaken for idyllic lovers, as well as the infamous red barn itself. In one version, Corder stands in the open door, inviting Marten to join him inside. The actual barn in Suffolk was ripped apart by thousands of souvenir seekers.

A set of the Red Barn figures via bonhams.com.

While murder memorabilia was in a frenzy in 19th-century England, these figures were also a visual portal into the crimes at a time when illiteracy was high. Myrna Schkolne, author of the 2006 People, Passions, Pastimes, and Pleasures: Staffordshire Figures, 1810-1835, told Collectors Weekly that the earliest example of a ceramic murder souvenir is likely one of French Revolution leader Jean-Paul Marat killed by Charlotte Corday. “But it wasn’t until 1810 that inexpensive prints showing everyday things became widely available, and that also affected Staffordshire figures,” Schkolne explains. “Broadsides, or penny strips of newspaper depicting events of the day, were often made from cheap woodcut engravings and sold on street corners.”

Narratives and confessions of Lucretia P. Cannon, who was tried, convicted, and sentenced to be hung at Georgetown, Del., with two of her accomplices; containing an account of some of the most horrible and shocking murders ever committed by one of the female sex. New York, 1841.

The poisoners and bludgeoners sculpted with rosy cheeks were a new way to transmit these stories in the 19th century, yet they followed a long history of such wares. Murder pamphlets that related prominent crimes to a popular audience had already been popular for centuries. They started as single broadside sheets and expanded into small books with innovations in publishing. As J. A. Sharpe writes in Past & Present journal: “Ever since the popular press had been established in England, much of its output had been devoted to crime, its major concern being the sensational and newsworthy case: from the start the purveyors of popular literature were convinced, as a Victorian ballad-seller was to claim, that ‘there’s nothing beats a stunning good murder.’”

These pamphlets spread to the United States. Sometimes they were sold to spectators at an execution, although more frequently they were hawked in town squares and taverns for the many who could not make it to the event. They printed the perpetrator’s confession, proceedings of the trial, and graphic narratives of the crime. Many were illustrated. These engravings featured portraits of the murderer and their victim or victims, the locations of the crime, diagrams of the weapons, and even the act of the crime itself. These were not journalistic affairs, with publishers competing to get theirs out first with the most dramatic details.

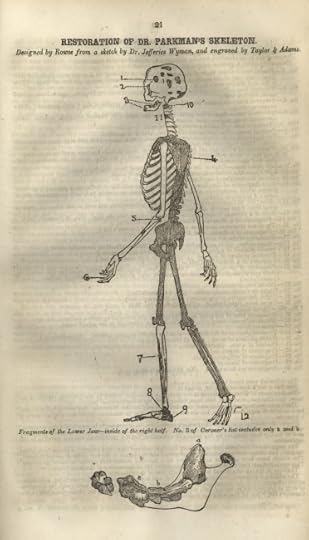

Trial of Professor John W. Webster, for the murder of Doctor George Parkman. Reported exclusively for the N.Y. Daily Globe. (New York, 1850).

The US National Library of Medicine has an online archive of these pamphlets. One for the 1830 trial of John Francis Knapp, accused of hiring a man to murder his uncle, included an illustration of the bludgeon “loaded with lead” used to carry out the deed, while the 1845 pamphlet on the trial of Abner Baker for murdering his brother-in-law begins with an elaborate map of the jail and courthouse. An especially popular subject was the 1849 murder of Dr. George Parkman. These relayed all the gruesome details of his death, such as the dismembered body parts found at the dissecting laboratory of Dr. John Webster which led to his hanging for the crime. Pamphlets illustrated the decayed remains, the restoration of Parkman’s skeleton from the severed parts, and Webster’s prison cell.

By the 20th century, these pamphlets were replaced with cheap paperbacks which continued to disseminate methodical chronicles of crime. With each new evolution of media, crime has always crept in with its secondhand thrills. Although there are ethical questions about how murder is so quickly turned into entertainment, it is a reflection of how these safe brushes with mortality — when everyday life can be disrupted by horror — remain a source of lurid fascination.

Allison C. Meier is a Brooklyn-based writer focused on history and visual culture. Previously, she was a staff writer at Hyperallergic and senior editor at Atlas Obscura. She moonlights as a cemetery tour guide.

If you enjoyed this piece, please consider supporting our work. Your contribution goes directly toward running The Order, including resources, research, paying our writers and staff, creating videos, podcasts, events and funding more frequent content. We’d love to keep pushing the funerary envelope in 2019. Visit our Support Us page, for a variety of easy ways to contribute, or become a patron on Patreon for exclusive content and rewards.

Victorian Murder Collectibles and Our Enduring Fascination With True Crime

July 22, 2019

The Cadaver in the Drag Queen’s Closet

Caitlin Doughty's Blog

- Caitlin Doughty's profile

- 8406 followers