Caitlin Doughty's Blog, page 19

August 3, 2018

Ask a Mortician: ADIPOCERE aka CORPSE WAX

August 1, 2018

The Stained and Sordid Scene: The Dead of Antietam

In October of 1862, photographer Matthew Brady’s gallery at Broadway and Tenth Street in New York City announced a new display. “The Dead of Antietam,” read a simple sign over the door. The Battle of Antietam, still considered the single bloodiest day in American history with over 22,000 killed or wounded, was just weeks earlier on September 17 near Sharpsburg, Maryland. The crowds which queued for hours to enter Brady’s gallery witnessed something unprecedented: photographs of corpses on the battlefield.

Alexander Gardner, “Killed at the Battle of Antietam” (1862), albumen silver print on card mount (Library of Congress)

Both Union and Confederate soldiers were tangled together in otherwise bucolic landscapes, with bodies awaiting burial lined up unceremoniously on the grass. The photographs were detailed enough to make out faces, their features bloated but distinct, which visitors quietly examined with shock and fascination. A horse crumpled on the ground regarded the viewers with a vacant expression; a peaceful white church was pocked by bullet holes. In an eloquent article in the October 20, 1862 New York Times, one writer contrasted these images to the tallies of the dead printed each day in the newspaper: “Each of these little names that the printer struck off so lightly last night, whistling over his work, and that we speak with a clip of the tongue, represents a bleeding, mangled corpse. … Mr. Brady has done something to bring home to us the terrible reality and earnestness of war. If he has not brought bodies and laid them in our dooryards and along the streets, he has done something very like it.”

“Gathered together for burial, after the Battle of Antietam” (1862), stereograph (New York Public Library)

Although Brady’s name was stamped on all the glass plate prints and stereographs, it was actually his employee Alexander Gardner with the assistance of James Gibson who had lugged the cumbersome photography equipment and developing chemicals to the battlefield. “Gardner and Gibson had taken seventy views in the smoky aftermath of Antietam, the first time photographers had been on the scene before the burial details had performed their somber services,” wrote Jennifer Armstrong in Photo by Brady: A Picture of the Civil War.

Physician and poet Oliver Wendell Holmes, who searched for his son at Antietam following the battle, described their impact: “Many people would not look at this series … It was so nearly like visiting the battle-field to look over these views, that all the emotions excited by the actual sight of the stained and sordid scene, strewed with rags and wrecks, came back to us, and we buried them in the recesses of our cabinets as we would have buried the mutilated remains of the dead they too vividly represented.”

Alexander Gardner, “Gardner’s Gallery, 7th and D Streets, Washington, D.C.” (1864), albumen silver print from glass negative (Gilman Collection, Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Gardner’s work still influences our perception of the Civil War, the grisly photographs maintaining their quiet savagery, and undercurrent of voyeurism. The images were such a success that Gardner, a Scottish immigrant, left Brady’s team and set up his own studio and gallery at 7th and D streets in Washington, DC. An captures it covered with signs advertising ambrotypes, cartes de visite, stereographs, album cards and, in the biggest letters of all, “VIEWS OF WAR.”

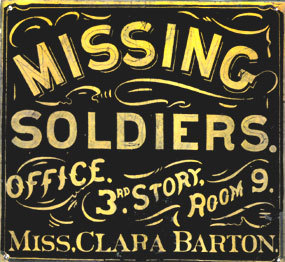

It’s near that intersection that the Clara Barton Missing Soldiers Office Museum is recreating the original display of Gardner’s photographs. (The nurse and Red Cross founder Clara Barton was herself at the Battle of Antietam, working non-stop even after a stray bullet shot through her sleeve and killed a soldier she was treating.) “Gardner’s gallery was located in the same block of 7th Street N.W. as was Clara Barton’s office,” said Bob Kozak, who organized the exhibition. “In some ways, the photos have come home.”

It’s near that intersection that the Clara Barton Missing Soldiers Office Museum is recreating the original display of Gardner’s photographs. (The nurse and Red Cross founder Clara Barton was herself at the Battle of Antietam, working non-stop even after a stray bullet shot through her sleeve and killed a soldier she was treating.) “Gardner’s gallery was located in the same block of 7th Street N.W. as was Clara Barton’s office,” said Bob Kozak, who organized the exhibition. “In some ways, the photos have come home.”

Called War on Our Doorsteps, the show is at the Missing Soldiers Office Museum through November 3. It was previously at the Antietam National Battlefield and the National Museum of Civil War Medicine in Frederick, Maryland. “After some research we discovered that no one in 150 years had ever restaged the exhibit and explored its impact,” Kozak said. “The Maryland government gave us a grant, which we matched, and we were off to the races. Many hours of research and reading 1862-63 era columns and articles, as well as comparing the photos to contemporary woodcuts based on the photos, showed us how several levels of censorship emerged.”

Newspapers in the 19th century did not have the technological capability to print photographs, and these woodcuts softened Gardner’s photographs, eliminating the gore so the soldiers appeared more asleep than dead. Much of the images’ power was in their suggestion that these anonymous individuals, left to rot in the open air, could be anyone, a son, a brother, a friend. There was some effort in the captions to distinguish Union from Confederate soldiers; the photographs themselves had no distinctions between sides.

Alexander Gardner’s 1865-66 Photographic Sketch Book of the War, featured a photograph by Timothy H. O’Sullivan from July 1863, titled “A Harvest of Death,” showing the body-strewn battlefield of Gettysburg. Gardner wrote that photography like this “shows the blank horror and reality of war, in opposition to its pageantry. Here are the dreadful details! Let them aid in preventing such another calamity falling upon the nation.”

“Ditch on right wing, where a large number of rebels were killed at the Battle of Antietam” (1862), albumen silver print on card mount (Library of Congress)

Did these photographs change perceptions of the human cost of war? The influence of the Civil War on photography is well-documented, and Gardner’s photographs are significant as some of the first acts of photojournalism. (However they should not be taken as objective truth; Gardner infamously posed a dead soldier at Gettysburg to get a better composition.) Yet 150 years later, we remain uneasy about the corpses of conflict. Only in 2009 was a 1991 ban on photographing the coffins of American soldiers lifted. Before that a photograph by a government contractor named Tami Silicio of 20 coffins traveling from Kuwait to Delaware was published on the April 18, 2004 front page of the New York Times, sparking debate on censorship and privacy. Even with the present ubiquity of photography, the scenes we see of war rarely have that aching silence of Gardner’s Antietam images, their depictions of death still radical in their stillness.

Allison C. Meier is a Brooklyn-based writer focused on history and visual culture. Previously, she was a staff writer at Hyperallergic and senior editor at Atlas Obscura. She moonlights as a cemetery tour guide.

If you enjoyed this piece, please consider supporting our work. Your contribution goes directly toward running The Order, including resources, research, paying our writers and staff, and funding more frequent content. We’d love to keep pushing the funerary envelope in 2018. Visit our Support Us page, for a variety of easy ways to contribute.

July 31, 2018

ICONIC CORPSE: Charles Byrne the Irish Giant

July 25, 2018

Am I too attached to a long-dead Portuguese serial killer?

When I first wrote about Diogo Alves, the 19th century Portuguese serial killer who was sentenced to death and had his head preserved in a jar, I didn’t expect the entire world would pounce on his story. It held interest to me –I am a criminology graduate with a master of Forensic Sciences and part-time researcher of the display of dead bodies–but it was hard to imagine a mainstream audience being interested in this man’s pickled head.

Then again, it was the photos. It’s always the photos.

Diogo Alves’ head. Photograph by RAFAELA FERRAZ.

Alves found his way far and wide: he was on Wired and Dangerous Minds, on Portuguese and French and Indian newspapers, on Time Out magazine under “attractions” in the Portuguese capital. A few months went by and he got to travel outside of Lisbon, to star in a Coimbra-based exhibit about the 150th anniversary of the abolition of the death penalty in Portugal. When the news broke, people congratulated me, like I’d somehow enabled his little outing.

I went to visit, of course. Alves was tucked away in the “dark” side of the exhibit (as opposed to the “light” side, which chronicled the abolition movement). The fluid inside his jar had been replaced since I’d last seen him, rendering his features a little clearer, and I smiled at the detail. Rather than an act of museological preservation, it felt like an act of kindness towards a fellow human being.

A part of me appreciated it. Another wondered if he deserved it.

The over-humanization of men who do horrible things is pervasive. It’s present in the way we glorify their unlikeability and lone wolfishness in fiction, in shows like Dexter and Hannibal, but also in the way we dedicate endless minutes of primetime television to the lives and times of mass shooters, serial killers, and other sensationally violent offenders. We’re helpless in the face of our own curiosity. We yearn to know more, and there’s nothing surprising about it: in a society that still upholds the male experience as universal, these men’s criminal exploits merely add another layer of complexity to their already full-fledged personhood.

This was very much on my mind, the day I smiled at Diogo Alves.

It wasn’t uncommon, in college, for classmates to break into delighted smiles every time the curriculum took a turn towards the serial killer, that most glorified of male offenders. “I just love them,” these classmates would whisper, taking notes to fuel late-night Google searches. This fascination was assumed to be shared by the rest of us, fellow students of crime and punishment, and for good reason: society at large seems to be downright obsessed with serial killers.

It wasn’t uncommon, in college, for classmates to break into delighted smiles every time the curriculum took a turn towards the serial killer, that most glorified of male offenders. “I just love them,” these classmates would whisper, taking notes to fuel late-night Google searches. This fascination was assumed to be shared by the rest of us, fellow students of crime and punishment, and for good reason: society at large seems to be downright obsessed with serial killers.

We have come to ascribe an awful lot of positive traits to the archetypal serial killer: he is mysterious and elusive, but still charming; he may be handsome in that tousled, boyish way, or strait-laced and cuff-linked to perfection; he may be a selfish bon vivant or a strict, almost ascetic character, but his disregard for others is always portrayed as aspirational, a mere consequence of his greatness of intellect. Far from someone who can’t fit in, he has actively chosen to stay out. Pages and pages are penned on his methods, his motivations, and his work-life balance.

It’s an interesting fantasy, but still just a fantasy.

Diogo Alves was none of the things we’ve come to expect from highly romanticized serial killers. In 1830s Lisbon, his proverbial work-life seesaw tipped only once, and never recovered. His original reputation as an honest worker and a man of his word was quickly replaced by that of a violent, petty man who cared for little more than drink and cash—and would resort to brutality for both. There was no glamorous finesse to his crimes, no intellectual prowess to be admired: he’d wait in the walkway atop the Águas Livres aqueduct for an unsuspecting victim and pull a knife on them. As soon as they’d handed over their valuables, he’d wrestle them towards the 200-hundred feet drop. There was some mystery about his person, sure, but only in the sense that there was never enough evidence to convict him. When he finally went to court, and then to the gallows, it was for a robbery-turned-quadruple-murder in a wealthy physician’s house.

Alves is often promoted as the last man Portugal sentenced to death, all the way back in 1841. He wasn’t, but the dates aren’t that far off: the very last man would meet his end in 1846, and capital punishment would go on to be abolished in 1867.

This illustration, which appeared in Sousa Costa’s “Grandes Dramas Judiciários” (1944), portrays Alves during his trial.

There was a reading, during Alves’ trial. A man, possibly Alves’ defense attorney (sources are unclear), stood before the court and read an excerpt from Cesare Beccaria’s 1764 treaty On Crimes and Punishments, hoping to sway the jury away from a death sentence. Even though he failed, he’d chosen his material well: Cesare Beccaria and Jeremy Bentham (yes, that Bentham) formed the backbone of the Classical School of Criminology, and both were against the death penalty. They believed offenders committed crimes not because of a moral failure or an innate propensity, but because crimes were objectively worth committing. To correct this, Beccaria and Bentham suggested a legal system that emphasized the detection and prompt punishment of each and every infraction—no exceptions, no delays. The certainty of being swiftly caught and brought to justice would surely dissuade the would-be offender, with no need to resort to the pointless cruelty of capital punishment.

This is a very logical mindset, but also a very empathetic one. Unlike other schools of thought, whose representatives argued for the animalistic, barely human qualities of “the criminal man”, Beccaria and Bentham’s focus on rationality and dissuasion acknowledged the offender as a fellow human being, no matter who they were or what they’d done. Furthermore, it drew attention to the reality of the death penalty as an unpredictable, arbitrary, and abusive form of punishment–characteristics it still hasn’t shed, and probably never will.

_______________________

Word on the street says Alves pushed close to seventy people from the walkway atop the aqueduct, but there is no way to prove this figure, no way to distinguish his victims from those claimed by another, quieter killer—suicide. All through the 1830s and 1840s, the Águas Livres aqueduct offered an option to those set on taking their own lives, and many were desperate enough to accept. This tragic reputation would come to provide much needed camouflage for Alves’ operation.

We know his victims only for their collective name: saloios, inhabitants of the rural suburbs of Lisbon who walked in and out of the city every single day, intent on selling their produce in its many markets. Although some were certainly comfortable, they were far from wealthy, which is perhaps, the only explanation we need to understand the lack of written sources regarding their deaths.

Águas Livres Aqueduct.

We have the story, however, of the people whose deaths would eventually lead Alves to the gallows. It all happened on the night of the 26th of September 1839. The address, 16 Rua das Flores, was home to a wealthy physician by the name of Pedro de Andrade, his footman Manuel Alves (no relation, at least familiar, to Diogo Alves), his housekeeper Maria da Conceição Correia Mourão, and her two daughters, 19-year-old Emília and 17-year-old Vicência. On the night of the murders, there was also a visitor: José Elias, the housekeeper’s 25-year-old son, a sailor just landing from a long assignment at sea.

That night, the physician had gone elsewhere on a social call; the housekeeper had requested his permission to use the dining room to serve a homecoming supper to her son, which he had granted; and the footman, taking advantage of all these arrangements, had made plans of his own. For a cut of the profits, he’d agreed to unlock the doors for a local gang, who’d long wished to divest the wealthy physician of his seemingly endless riches.

This gang was, of course, led by Diogo Alves, but there’s little need to delve into his modus operandi for the night. The robbery soon turned violent. José Elias, the housekeeper’s son, fought tooth and nail to repel the thieves, but there was no reward for his bravery—all four members of the family would die at Alves’ hand.

Upon discovery the next morning, the bodies were autopsied and flung into a common grave. The wealthy physician, it seems, refused to pay for their burial. As for the footman, Manuel Alves, he survived the night but wouldn’t survive his association with Diogo Alves. Unsure of his loyalties, the gang killed and disposed of his body soon after the robbery, never to be mentioned again.

Photograph by RAFAELA FERRAZ.

It’s unclear why the family from Rua das Flores, whose names and faces the law knew, mattered more than the dozens of saloios whose lives were cut short in the aqueduct. It is clear, however, that even these four didn’t matter enough. Sources suggest that it was the physician’s reputation that carried the crime to court: Lisbon would not tolerate violence against the house of one of its finest. Today, we know the precise number of knives, candlesticks, brooches and gold watches which were stolen from the physician’s cache, but we don’t know where the bodies of Maria da Conceição Correia Mourão and her three children were put to rest. If we wanted to pay our respects to this family, to honor the cheerful supper they’d planned for their reunion, we’d have no choice but to visit 16 Rua das Flores, the site of their murder. It’s a pink house, these days, and despite the growing touristification of the area, there’s nothing on the floor level but a nondescript door. There, perhaps, we would deposit our flowers.

As I see it, and as I tell it, the story of Diogo Alves is a story of bodies that matter and bodies that don’t. The aqueduct victims didn’t matter. The Flores victims didn’t matter. Alves himself didn’t matter, not in the empathetic sense: that we know of him today is merely a testament to the dehumanization of criminal offenders in the 1800s.

It was the 19th century’s scientific obsession with the physical features of criminals that led to the preservation of Alves’s head, allowing him to evade the common grave and claim a spot in a medical school instead. Up on a shelf, joined by many of his contemporaries, he found himself a new allegiance: no longer just a serial killer, no longer just one of the last men killed by the Portuguese death penalty, he now became a preserved human specimen.

Jeremy Bentham, he of the Classical School, also requested that a friend preserve his body for posterity. A twist of fate made it so his head ended up separate from his body, but no matter. Bentham got exactly what he wanted.

There is a privilege to being able to dictate what happens to our corpse, a privilege that, historically, hasn’t been shared with the people whose bodies actually make up the bulk of anatomical and anthropological collections. I don’t know if Alves would have consented to his own display, but I can speculate: Catholic as he was, it’s likely he would have been shaken by the sight of his own head on a shelf.

Some will say he deserved, and continues to deserve, this presumed offense to his self-determination. Maria da Conceição Correia Mourão and her children didn’t get the right to a proper burial, why should their murderer?

Yet I feel differently.

I feel they all deserved better.

_____________________

That Diogo Alves’ victims did not receive proper burials is as much a product of the time as his own execution and his head’s consequent display. The mindset that allowed for one disrespectful act allowed for the other, and showed remorse for neither. Today, the state would have assured the victims were sent off with dignity, even if friends and family couldn’t afford it; today, Alves would have been sentenced to a maximum of 25 years in prison. He would not have been studied, nor put on display, unless he’d explicitly signed his consent.

Portugal is no longer the country these people knew, but the pickled head-in-a-jar, which I’ve gone to visit six times now, is a relic of a time they would have recognized.

I’m still not sure why I smiled at it, that day.

Perhaps I was just over-humanizing a man who’s done horrible things. Or perhaps I was trying, to the best of my ability, to engage with an object that I still can’t fully comprehend, along with all the history it holds in that crystal-clear, just-replaced batch of preserving fluid.

Rafaela Ferraz is a writer of short stories, essays, and a variety of articles on strange, slightly macabre, and often overlooked chapters of Portuguese history. She blogs at rafaelaferraz.com, conducts research on the collection and display of human remains on Patreon, and tweets @RafaelaWrites

If you enjoyed this piece, please consider supporting our work. Your contribution goes directly toward running The Order, including resources, research, paying our writers and staff, and funding more frequent content. We’d love to keep pushing the funerary envelope in 2018. Visit our Support Us page, for a variety of easy ways to contribute.

July 21, 2018

The Mysterious Cave of Glowing Skulls

July 18, 2018

YEAR OF ACTION: The Good Death Art Show

In April of 2018, Chicana artist, Abby Rocha, curated a death positive art show at San Francisco’s Sketchpad Gallery. She says:

My intention in the creation of “The Good Death Art Show” was not only to curate an exhibit at Sketchpad Gallery very different than previous shows, but to also have a conversation with the public about the multi-faceted subject of death. I wanted artists to use visual storytelling to speak about their relationship with death, either cultural, personal or other. In many ways, the artists surpassed my expectations, they opened up and spoke about those whose stories never were told, cut short or those who left a deep impact in their lives. They talked about death in culture, their fears, their hopes and some even poked fun at the great unknown.

Departure, by Hsing Yi “Cindy” Lee.

“The ones we lost moved on, but their love will always remain to keep us going.”

Hsing Yi Lee, Cindy, is originally from Taichung, Taiwan and came to the U.S. five years ago to study art. Since graduation, she has done freelance work as an illustrator and helped with visual art on a few collaborative animation projects. She aspires to become a great visual storyteller.

How to Navigate Despair, by Dean Stuart.

“After losing someone special, life becomes an ocean we must learn how to navigate.”

Dean Stuart is an illustrator and gallery artist, He’s created work for magazines, books, and galleries for the past several years. He works out of his studio space at The Compound Gallery in Oakland, CA.

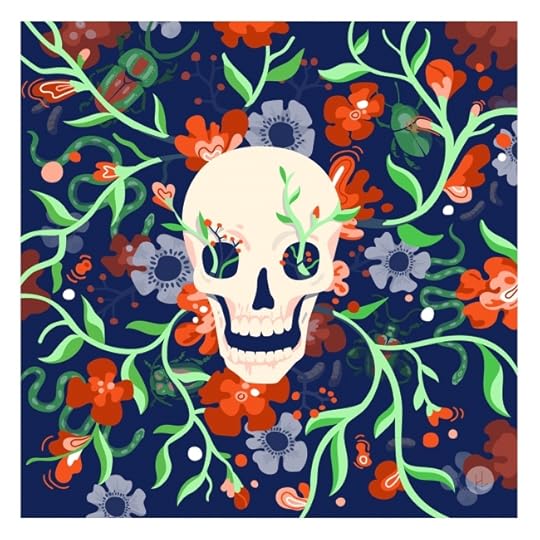

Our Lady of Holy Death, by Ana Vee Valdez.

“Santa Muerte is a folk saint and the residue of many Mexican and Chicana’s indigenous roots. She is part folk-catholic saint, an undertaker and escort to the spirit world and part death goddess, stemming from an instance of the syncretism of Mictecacihuatl (the skeletal death Aztec death goddess). She is a protector, a server of justice, and an ethereal advocate for those who have suffered abuse or misfortune.”

Ana Vee Valdez is an Bay Area illustrator, Artist, a folk catholic and a witch. Her work heavily is influenced by her mestiza background, queerness, the occult and nature.

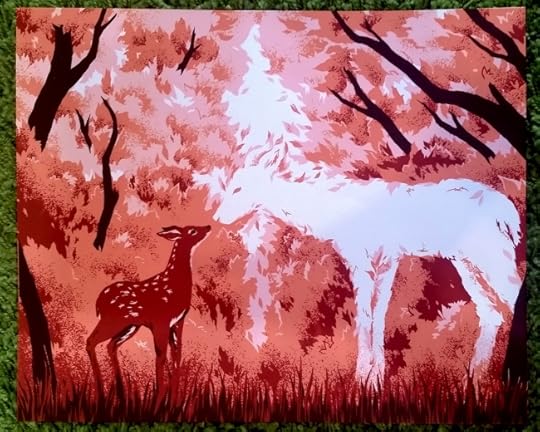

The Earnest Work, by Tiffany Turrill.

“…Each of us is given

only so many mornings to do it –

to look around and love the oily fur of our lives,

the hoof and the grass-stained muzzle.

Days I don’t do this I feel the terror of idleness,

like a red thirst…

When we die the body breaks open like a river;

the old body goes on, climbing the hill.

– Mary Oliver”

Tiffany Turrill is a fantasy illustrator who creates work for publishing and game companies. She specializes in dark fantasy, folklore and zoology. She lives in the East Bay, CA.

Regeneration, by Krystal Lauk

“Some people want to live forever, and advances in technology may make this possible one day. But only with death can fresh ways of thinking and new ideas grow with new generations. This is why death is not only good, it is necessary. “

Krystal Lauk is an illustrator and visual designer living in San Francisco, and worked with clients such as Google, Facebook, Uber, Fast Company, UC Berkeley and Column Five. Her work has been recognized by American Illustration, the Society of Illustrators, and 3×3 magazine.

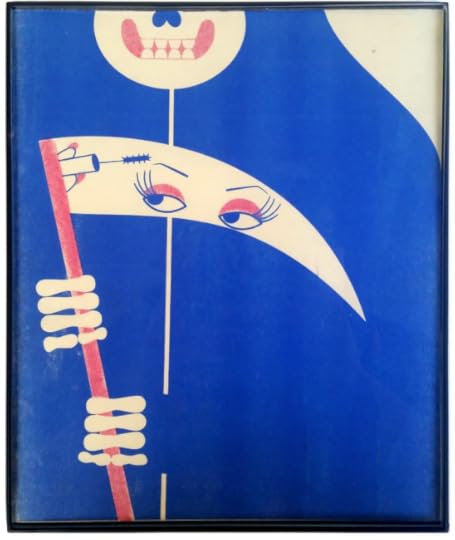

Date With Death, by Michelle McNeil

“Get ready, look sharp—your date will be here before you know it!.”

Michelle McNeil is a designer and illustrator in San Francisco. She works as a graphic artist at the San Francisco Public Library.

Always With Us, by Kimberly Cho

“When we lose an loved one, it feels as though they have left a gaping hole in our hearts. However, they have also left an imprint in our memories. When we reminisce about those we love, it makes us feel, in that instance, they will always be with us.”

Kimberly Cho is a San Francisco based illustrator from Taiwan. She enjoys exploring new places, near or far, and eating amazing food. However, she is usually found binge watching a TV show or doing a movie marathon.

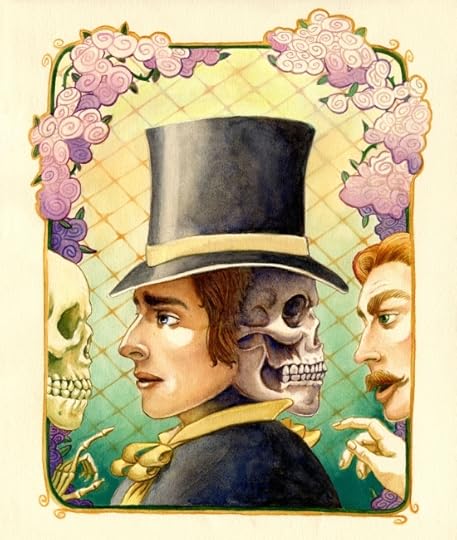

Baron, by Duke Duel

Baron, by Duke Duel

“Baron Samedi, the Loa of Sex, Death and Saturday night. Baron Samedi can usually be found at the crossroads between the worlds of the living and the dead. When someone dies, he greets their soul after they have been buried, leading them to the underworld..”

Duke Duel is an artist and sign maker.

Memento Mori, by Abby Rocha

“Memento mori is a Latin phrase meaning ‘Remember you must die’. The Victorians were steeped into an era of melancholy for over 40 years when the Prince Consort, husband of their Monarch Queen Victoria, died and she went into perpetual mourning. It became fashionable and even good etiquette to be obsessed with death and mourning.”

Abigail Piña Rocha is a Chicana Illustrator based out of beautiful Oakland, California. She creates illustrations, comics and murals and her work often has political/social commentary about Latinx culture as well as the world around her. As a failing goth in recovery, she is an advocate of the death positive community.

July 13, 2018

Corpse Control (Know Your Rights)

July 11, 2018

They’re Not Morbid, They’re About Love: The Hair Relics of the Midwest

The docent at Leila’s museum stresses to me that the collection I’m looking at isn’t about death, but her words are less than convincing. For one thing, I suspect that all collections are about death. Collectors, by nature, unite formerly unrelated objects. They rearrange them, explain their context and give them new contexts by linking them to the life of the person who amassed them Then they’re displayed until the collection become a piece of a person’s identity: my Aunt Rose Mary and her Irish Wolfhounds, Jay Leno and his cars, Eli Broad and his art. But unlike their owners, the collections don’t die. To collect is to illustrate your life in objects, curating your legacy, that little immortal piece of our identity that’s left behind. But I don’t think that’s what the docent is referring to. If Leila’s museum seems to be about death, it’s because the hair of the dead covers every available wall. Leila collects art that’s made of human hair and displays it to the public at the museum bearing her name in Independence, Missouri.

“A lot of people think hair art is morbid but it’s really about love”, the docent on duty insists as I take in a hundred or so mousey-brown wreaths and crosses occupying the front room. She can’t see my eyebrow arch because my gaze has settled on a funeral wreath of hair and the words MEL 1877, also made of hair, beneath it. The Victorians had strange ways of showing they cared.

The majority of Leila’s collection is from the Victorian period which stretched from 1837 to 1901. Like bustled black dresses or silver lachrymatory used to bottle tears (also on display in Leila’s vestibule), hair jewelry was part of the pageant of mourning in the mid to late 19thcentury. Hair was sometimes taken from the dead, wrapped around wire and worked into filigree sculptures then preserved under glass. In other cases the hair of the deceased was used to make jewelry which was considered modest enough to wear during mourning when most pieces would have to be retired for a year and a day. This funereal context is how we think of hairwork today if we think of it at all, but the docent is correct, most of it wasn’t so grim. Families tracked genealogy through horseshoe-shaped wreaths and documented each relation with labeled flowers made from their hair. Women exchanged locks as tokens of friendship. Weddings were commemorated by weaving the couple’s hair together or by a wife making her husband a fob or ring of her hair to keep with him.

There are examples of all of these types of hairwork at Leila’s museum. The museum itself is housed in a generic 70s commercial building that looks like it ought to be a Goodwill or a used car dealership. The mirrored windows make it look vacant from the outside and inside the fluorescent lights add to the funeral pall which the docent is eager to cast off. She tells me about the museum’s namesake: Leila Cohoon, the retired beautician who became fascinated with human hair art when she bought her first piece at an antiques shop in 1956. She’s been exhibiting her collection to the public since 1986. Leila is alive and well but she isn’t at the museum today except in the way that she always is—in a frame near the door where she’s shaped clippings from her platinum bouffant into a bedazzled spray of daisies. The docent tells me that Leila used Elmer’s glue to hold the strands together but the Victorians probably would have used egg whites or sugar water. Of the thirty techniques that Leila has identified for making hair art, she practices twenty-six.

Despite my tour guide’s initial protestations and the liveliness of Leila’s daisies, the specter of death is always near, even when the hair pieces weren’t created for mourning. One family tree lists the marriage and death dates for all but one daughter. “So we know who made this piece” the docent points out as I imagine this last daughter, never married, documenting the death of her entire family. Another family piece is simpler—children’s hair arranged in ringlets by their mother. Each child has multiple entries so you can see their baby-fine hair get coarser and darker over time, except for the youngest who only has one entry at three weeks. Freud had a theory about collecting. He saw it as a reaction to the separation anxiety and loss of control we felt as children when our bodily fluids came out of us and were taken away. In a way it reminds me of this mother who collected her children, including the lost child, which were once a part of her. Freud’s focus on bodily functions seems crude but the corporeality seems right. It’s easy to see how small pieces of people could be cherished and collected in an era when death came too soon and even young people amassed collections of dead friends. This difficult truth turns up unexpectedly in a wreath made of brightly dyed white horsehair—an unexpected rainbow in a sea of chestnut brown and dishwater blonde. The docent notes that white hair art is almost always from horses— many in the Victorian era never lived to go gray.

Implied tragedy is everywhere and carries over to a wall that features the framed hair of dead celebrities, mostly bought by Leila online. There are barely visible strands of Marilyn Monroe, Elvis, Michael Jackson and Ronald Regan—all usual, and in their own ways, tragic subjects of modern veneration. All people whom so many wanted a piece of, though usually not so literally. Memories of the celebrities are sparked whenever someone sees this little piece of them so their presence is always felt here. In this way they resemble some of the earliest body part collections—the royal relic collections of the Middle Ages.

There’s a concept in Catholicism that says that the body and soul of a saint (a Catholic kind of celebrity) are inextricable from each other so the presence of a saint is stronger at the place where their body, or at least a piece of it, rests. Because of this, the bodies of saints were divided into smaller and smaller pieces to maximize their power and medieval kings set about collecting them. As they added new pieces, they were also putting together a kind of cabinet—a team of powerful miracle workers they could call upon since the remains of these saints were forever tied to their souls in heaven. Like other collectors, the gathering of objects soothed their fear of death. These collections and the legacy of the kings who collected them, would live on with the added hope that the saints they hoarded would welcome them into the afterlife.

There’s a concept in Catholicism that says that the body and soul of a saint (a Catholic kind of celebrity) are inextricable from each other so the presence of a saint is stronger at the place where their body, or at least a piece of it, rests. Because of this, the bodies of saints were divided into smaller and smaller pieces to maximize their power and medieval kings set about collecting them. As they added new pieces, they were also putting together a kind of cabinet—a team of powerful miracle workers they could call upon since the remains of these saints were forever tied to their souls in heaven. Like other collectors, the gathering of objects soothed their fear of death. These collections and the legacy of the kings who collected them, would live on with the added hope that the saints they hoarded would welcome them into the afterlife.

Though she isn’t Catholic, Leila keeps a number of reliquaries with the hair of saints. One of them contains what Leila believes is a hair from the head of St. Anne. Another hair allegedly belongs to the Virgin Mary. That one is a highlight of the museum, displayed with a red wax seal and a mysterious story about its acquisition from an unnamed antiquities dealer in Belgium.

As I turn from the reliquaries, I notice a hair wreath with a crumbling taxidermied bird perched on top. My tour guide tells me that what makes the museum possible is that unlike the bird, hair is curiously incorrupt. According to her, it doesn’t decay. That isn’t quite right, hair decays like all organic material, but it does disintegrate at a much slower rate than flesh. Still, she says even Mary’s hair will look as fresh in another thousand years as it does today and she very well could be right. But what’s curious is that though hair may survive, like collections long after the collector, death is also intrinsic to hair. By the time you can see it on your body it’s no longer alive. This is part of what makes it such an unsettling medium: that which is dead, that which should be buried, is not only visible but on display in hair art.

The docent acknowledges that hair art is not for everyone. It makes some people queasy and it’s fairly common to see husbands holding a purse in the lobby while their wives take a tour of the museum. But I look at a display of little hair rings and lovers’ lockets again. I wonder if what unnerves these staid Midwestern men isn’t the medium, but the message. These pieces represent a raw sentimentality untouched by cynicism. They’re a refusal to part with another. Hair art speaks to our most vulnerable feelings: love and grief, all in the form of a sculpture or the braided bands that were made to be worn around the upper arm—literally on one’s sleeve.

Order member, Elizabeth Harper writes about Catholic relics and oddities on her blog All the Saints You Should Know. Her essays and photographs have appeared in Atlas Obscura, Hazlitt, Slate, and VICE Italia. She has lectured on incorrupt saints at the Mütter Museum as part of Death Salon and on the Neapolitan Cult of the Dead as part of the Bishop Walter Sullivan Lecture Series at Virginia Commonwealth University. She recently contributed an essay to Death: A Graveside Companion, and her photographs of incorrupt saints are featured in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s catalog The Body in Color.

If you enjoyed this piece, please consider supporting our work. Your contribution goes directly toward running The Order, including resources, research, paying our writers and staff, and funding more frequent content. We’d love to keep pushing the funerary envelope in 2018. Visit our Support Us page, for a variety of easy ways to contribute.

They’re Not Morbid, They’re About Love: The Hair Relics of the Midwest

July 6, 2018

CARING FOR THE BODIES OF TERRORISTS

July 1, 2018

MORTICIAN RECRUITS TEENAGERS AT VIDCON

Caitlin Doughty's Blog

- Caitlin Doughty's profile

- 8406 followers