Esther Crain's Blog, page 57

November 29, 2021

An 1873 map shows rural Brooklyn on the cusp of big changes

I can’t help but get lost in the Beers Map of Gravesend. Drawn in 1873 by cartographer Frederick Beers, it’s an impressive survey of one of the original six towns of Brooklyn—founded in 1643 by English-born Lady Deborah Moody and her group of Anabaptist followers, according to heartofconeyisland.com.

What amazes me most is how rural this pocket of southern Brooklyn was in the 1870s—and how much change was right on the horizon. (If you can’t magnify the map above, try visiting this link.)

First, look at that craggy shoreline of Coney Island. At some point, as Coney transitioned into the beach resort dubbed the People’s Playground in the next few decades, all those inlets and little islands were filled in and straightened out—including Coney Island Creek, making Coney no longer an island.

And what about these villages with names like South Greenfield, Unionville, and Guntherville? Unionville was actually in New Utrecht, according to a Brooklyn Daily Eagle article. Guntherville, perhaps named after a landowner on the map named M. Gunther, must have been a similar farming hamlet.

South Greenfield “was a very quiet and peaceful farming community, and remained that way for half a century,” states the Kings Courier in 1960. Then the Vitograph film studio opened there in the early 1900s, ushering out the farms and bringing some short-lived movie-making glamour to the area.

Names of landowners appear in very small print, familiar ones to Brooklynites today like Emmons, Cropsey, Stillwell, Van Sicklen. Geographical names have a rural feel. There’s a Hog Point (or Pit?) just north of Sheepshead Bay. Indian Pond is on the New Utrecht border.

Big resort hotels on the ocean like the Oriental haven’t arrived quite yet, though the railroads are there—soon to bring upper middle class Manhattanites to Coney Island and not-yet-named Manhattan and Brighton Beaches.

But already by this time, Gravesend is a recreational area. Boat houses are on Gravesend Bay; small hotels dot the countryside. Coney Island Road (not yet Avenue) has Newton’s Grand Central Hotel. The Prospect Park Fair Grounds is a horserace track flanked by Floyds Hotel and Bretells Hotel.

The hotel action on the seashore was active as well: the Point Comfort House, Union Hotel, Beach House, Washington Hotel, and Ocean Hotel. I don’t think any made it into the 20th century, but they helped put Gravesend on the map as a place of relaxation, leisure, and the latest amusements for pleasure seekers.

[Map: Wikipedia; fourth image: NYPL]

November 28, 2021

The honorific street name near City Hall that commemorates a plague

Unless you know where to look, it’s hard to find. But on the east side of City Hall Park is a spot that honors people living with a disease considered a plague when it emerged in the early 1980s.

“People With A.I.D.S Plaza,” as the street sign reads, spans Park Row between Beekman and Spruce Streets, near the approach for the Brooklyn Bridge.

It’s technically an or a co-named street; both terms are used to described streets that have an official name but also a second one to commemorate a person or event. New York has over a thousand of these, such as “Rivera Avenue” for Mariano Rivera in front of Yankee Stadium, or the 3-block stretch of Worth Street co-named “Avenue of the Strongest” to honor city sanitation workers.

Clues about the backstory of People With A.I.D.S. Plaza aren’t easy to come by. The street may have been co-named in 1997, according to the Encyclopedia of New York City: Second Edition, but the wording isn’t clear. It’s not on a list of honorific street names compiled by a researcher named Gilbert Tauber.

Why City Hall? Possibly to mark the location where AIDS activists and allies held protests—like this one in 1989 organized by ACT UP, with more than 3,000 people protesting Mayor Koch’s handling of the disease.

Since People With A.I.D.S. Plaza was added to the map, New York has created more prominent memorials to the thousands of city residents living with AIDS or HIV, or who have died of the virus.

The New York City AIDS Memorial, dedicated in 2016 (above), is a pyramid-like steel sculpture at St. Vincent’s Triangle on Seventh Avenue and West 11th Street. Now the site of a small park, St. Vincent’s Triangle is across the street from the former St. Vincent’s Hospital—which in 1984 established the first AIDS ward in New York City, according to NYC Parks.

An earlier AIDS memorial, unveiled in 2008, is in Hudson River Park near Bank Street.

[Third photo: NYC Parks]

Life and humanity on the “wonderful roofs” of John Sloan’s New York

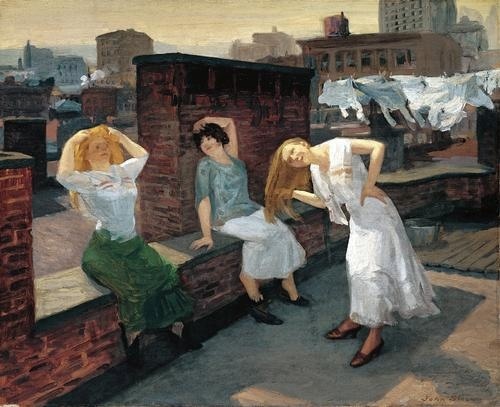

If you’re familiar with John Sloan’s Lower Manhattan paintings and illustrations from the first half of the 20th century, then you’ve probably noticed a running theme among them: tenement rooftops.

“Rain Rooftops West Fourth Street,” 1913

“Rain Rooftops West Fourth Street,” 1913Like other Ashcan and social realist artists of his era, Sloan was captivated by what he saw on these roofs—the people he surreptitiously watched; their mundane activities; their delight, despair, and sensuality; and the exquisite vantage points roofs offered of a city on the rise.

“Sunday Paper on the Roof,” 1918

“Sunday Paper on the Roof,” 1918“These wonderful roofs of New York City bring me all humanity,” Sloan said in 1919, about 15 years after he and his wife left his native Philadelphia and relocated first to Chelsea and then to Greenwich Village, according to the Hyde Collection, where an exhibit of Sloan’s roof paintings ran in 2019. “It is all the world.”

“Roof Chats,” 1944-1950

“Roof Chats,” 1944-1950“Work, play, love, sorrow, vanity, the schoolgirl, the old mother, the thief, the truant, the harlot,” Sloan stated, per an article in The Magazine Antiques. “I see them all down there without disguise.”

“Pigeons,” 1910

“Pigeons,” 1910His rooftop paintings and illustrations often depicted the city during summer, when New Yorkers went to their roofs to escape the stifling heat in tenement houses—socializing, taking pleasure in romance and love, and on the hottest days dragging up mattresses to sleep.

“I have always liked to watch the people in the summer, especially the way they live on the roofs,” the artist said, according to Reynolda House. “Coming to New York and finding a place to live where I could observe the backyards and rooftops behind our attic studio—it was a new and exciting experience.”

“Red Kimono on the Roof,” 1912

“Red Kimono on the Roof,” 1912Rooftops were something of a stage for Sloan. From his seat in his Greenwich Village studio on the 11th floor of a building at Sixth Avenue and West Fourth Street, Sloan could watch the theater of the city: a woman hanging her laundry, another reading the Sunday paper, a man training pigeons on top of a tenement and a rapt boy watching, dreaming.

Sloan described his 1912 painting, “Sunday, Women Drying Their Hair,” as “another of the human comedies which were regularly staged for my enjoyment by the humble roof-top players of Cornelia Street,” states the caption to this painting at the Addison Gallery of American Art.

“Sunday, Women Drying Their Hair,” 1912

“Sunday, Women Drying Their Hair,” 1912Of course, roofs also meant freedom. In the crowded, crumbling pockets of Lower Manhattan filled with the poor and working class New Yorkers who captured Sloan’s imagination, roofs conveyed a sense of “escape from the suffocating confines of New York tenement living,” wrote the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

“Sunbathers on the Roof,” 1941

“Sunbathers on the Roof,” 1941In the early 20th century, many progressive social reformers preferred to see these roof-dwelling New Yorkers in newly created parks and beaches, which were safer and less private.

But “Sloan embraced what he called ‘the roof life of the Metropolis’—as he did its street life—as a means to capture the human and aesthetic qualities of the urban everyday, a defining commitment of the Ashcan School,” wrote Nick Yablon in American Art in 2011.

November 21, 2021

Shopping for Thanksgiving dinner at Washington Market in the 1870s

“Washington Market, New York, Thanksgiving Time” is the straightforward name of this hand colored wood engraving. Drawn by French artist Jules Tavernier, the richly detailed image ran in Harper’s Weekly in 1872.

What does Tavernier’s image tell us? Basically, food shopping at Thanksgiving time was just as crowded and harried in the 1870s as it is today.

Instead of visiting Whole Foods or Trader Joe’s, New Yorkers could head to the shoddy wood stalls and wagons at the massive old Washington Market, in today’s Tribeca—where produce sellers hawked their goods from 1812 until the 1960s, when it gave way to redevelopment.

[Image: Philographikon.com]

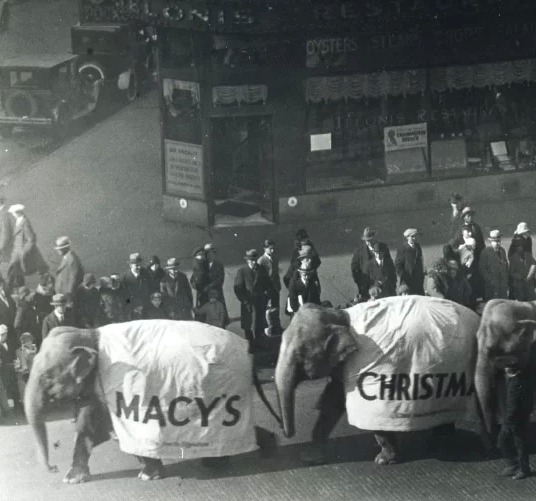

The modest 1924 beginning of Macy’s annual Thanksgiving Parade

New Yorkers know what to expect from Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade: towering balloon characters, marching bands, elaborate floats, and Santa Claus waving from his sleigh as the procession inches from Central Park West and 77th Street to Macy’s iconic Herald Square store.

It’s a beloved holiday tradition, but it’s notably different than the much more humble inaugural parade Macy’s held in 1924.

For starters, though the first parade was held on November 27—which was Thanksgiving Day in 1924—Macy’s called it a Christmas Parade. Store employees apparently came up with the idea.

“Earlier that year, a group of Macy’s employees who were largely first-generation immigrants had asked the company to put on a parade to celebrate two things: The upcoming Christmas season, and the pride they felt in their new country,” according to Better Homes & Gardens.

Macy’s corporate leaders may have liked the idea for another reason. “Macy’s hoped its ‘Christmas Parade’ would whet the appetites of consumers for a holiday shopping feast,” wrote history.com.

The first parade took a much longer route, starting at Convent Avenue and 145th Street and making its way to the flagship Macy’s on 34th Street. Opened in 1902 after Macy’s long reign on the 14th Street end of Ladies Mile, the massive shopping mecca was a mere 22 years old at the time.

Macy’s took out newspaper ads to let New York know about the parade, promising a “marathon of mirth,” per history.com. That tagline was often used to advertise vaudeville shows, and indeed, the first parade had something of a vaudeville-like feel. (Below, the small ad the Brooklyn Eagle ran announcing the upcoming parade.)

“While the parade route may not have extended over 26 miles, its 6-mile length certainly made for a long hike for those marching from Harlem to Herald Square,” the site continued. “The spectators who stood four and five people deep, however, could watch it all in just a matter of minutes since the modest street pageant stretched the length of only two city blocks.”

What about the entertainment? The parade had no balloon floats yet, but three floats pulled by horses were themed around Mother Goose characters, such as Little Miss Muffet (second photo). Macy’s employees also dressed up as clowns, cowboys, princesses, and knights, lending the parade a circus-like, stage show aura.

Animals were also featured, conveniently borrowed from the Central Park Zoo. “Live animals including camels, goats, elephants, and donkeys were part of the parade that inaugural year,” stated a 2011 New York Daily News piece.

While Santa Claus was at the rear of the parade, he didn’t disappear once the procession ended on 34th Street. “By noontime, the parade finally arrived at its end in front of Macy’s Herald Square store where 10,000 people cheered Santa as he descended from his sleigh,” wrote history.com.

Once he emerged from his sleigh, the site explained that Santa “scaled a ladder and sat on a gold throne mounted on top of the marquee above the store’s new 34th Street entrance near Seventh Avenue.”

Though the parade wasn’t widely covered the next day in the papers (above, a grainy photo from the Daily News of the parade on Broadway), it was a smashing success. Macy’s was so pleased, they vowed to do it again on Thanksgiving 1925.

In the 1920s it became an annual event, but not without big changes. The zoo animals were replaced by balloon floats (above, in 1926) and then actual balloon characters as we know them today. Felix the Cat was the first one, in 1927; unfortunately Felix collided with an electrical wire in New Jersey in 1931 and was no more.

The parade route was shortened, the crowds got huge, balloons were no longer released into the air after the parade ended, and the first TV broadcast in 1947 turned it into a national celebration marking the beginning of the holiday shopping season.

[Top photo: Macy’s via bhg.com; second and third photos: Macy’s; fourth image: newspapers.com; fourth and fifth images: newspapers.com; sixth and seventh images: Macy’s]

The Wild West-inspired apartment house designed for urban cliff dwellers

In Gilded Age New York, a new term popped up to mock a certain type of Manhattanite: cliff dweller.

“By about 1890 the growing number of residents in apartment houses were sardonically called cliff dwellers, after the image of the cliff-dwelling Native Americans in the Southwest,” wrote Irving Lewis Allen in his 1995 book, The City in Slang.

Inspired by the new slang term as well as Southwestern images and motifs, a new residential building opened its doors on Riverside Avenue and 96th Street in 1916: the aptly named Cliff Dwelling.

The 12-story Cliff Dwelling, situated on a flatiron-shaped plot only roughly eight feet deep on one side, opened as an apartment hotel high up over Riverside Park on posh Riverside Drive.

Unlike the restrained elegance that characterized similar new buildings on the Drive, the Cliff Dwelling had a playful, inventive facade unique in New York City.

Buffalo or cattle skulls, two-headed snakes, and mountain lions in terra cotta decorate the front of the building, along with images of corn, spears, and masks. Raised bricks form geometrical patterns and zigzags that mimic Aztec and Mayan design motifs.

Credit for the wildly original design goes to architect Herman Lee Meader, according to a 2002 New York Times article by Christopher Gray. “[Meader] was intensely interested in Mayan and Aztec architecture and made regular expeditions to Chichén Itzá in the Yucatán and other sites,” wrote Gray.

The Cliff Dwelling continued the Southwestern theme on the inside as well, stated Gray: “The lobby was furnished with Navajo rugs; tiles of tan, green, black and blood red; and zigzag designs on the lamps and elevator cages reminiscent of American Indian designs.”

By 1932, the Cliff Dwelling was converted to apartments, according to Carter Horsely at cityrealty.com, with kitchens added to the already small rooms. Since 1979, the building—which lost its marquee at some point, visible in the above 1939 photo—has been a co-op.

I’ve never been inside the Cliff Dwelling, but I imagine there’s still a sense of living high above an urban canyon, with a view to the Hudson and perhaps the New Jersey Palisades.

One recent change, however, may make the Cliff Dwelling feel more like a typical squeezed-in city structure: In the early 2000s, a new residential building was built inches away from the Cliff Dwelling’s eastern facade.

At least the western facade still has those wonderful tongue-out faces at eye level.

[Fourth photo: NYC Department of Records & Information Services]

November 15, 2021

A portrait painter’s shadowy figure on a nighttime city street

History has given John Bentz a low profile.

Born in 1853 in Ohio, Bentz may be best known as a portraitist and art restorer. He painted the rich and socially connected, and four years before his death at age 97, he was hired to clean paintings in City Hall, per a 1946 New York Daily News article.

But Bentz also painted landscapes, and one, titled “Journey to the End of the Night,” is this WPA-era nocturne of the cityscape—showing us a bedraggled, whiskered man, his hands in his front pockets looking straight ahead. The rough forms of pedestrians can be seen in the light in the background, around the corner but worlds away from the man.

Could this be a self-portrait of the artist, who would have been well into old age when the painting was completed in the 1930s or 1940s? With a dark sliver of a Gothic church on the left across from the well-lit figure stopped in his tracks under a modern red awning, is it a comment of sorts on death and immortality?

Or perhaps it’s an allegory on the passing of time: the revelers in the background on the sidewalk and on top of a double decker bus oblivious to the fact that one day, they will be the old whiskered man shuffling alone along a New York street.

November 14, 2021

What life was like with the elevated train roaring outside your window

“The elevated railroad, perpetually ‘tearing along’ on its stilted, aerial highway, was ‘an ever-active volcano over the heads of inoffensive citizens,” wrote one Australian visitor who came to New York in 1888.

38 Greenwich Street in 1914

38 Greenwich Street in 1914That description gives us an idea of the feel of Gotham in the late 19th century, when steam-powered (later electric) elevated trains carried by trestles and steel tracks ran overhead on Ninth, Sixth, Third, and Second Avenues.

The upside to the elevated was obvious: For a nickel (or a dime during off hours), people could travel up and down Manhattan much more quickly than by horse-drawn streetcar of carriage. New tenements, row houses, and entertainment venues popped up uptown, slowly emptying the lower city and giving people more breathing room.

Bronx, undated

Bronx, undatedThe downside? Dirt and din. The trains and tracks cast shadows along busy avenues, raining down dust and debris on pedestrians. (No wonder Gilded Age residents who could afford to changed their clothes multiple times a day!) And then there was the deafening noise every time a train chugged above your ears.

Now as unpleasant as the elevated trains could be in general, imagine having the tracks at eye level to your living quarters. Life with a train roaring by at all hours of the night was reality for thousands of New Yorkers, particularly downtown on slender streets designed for horsecars, not trestles.

Allen Street north of Canal Street, 1931

Allen Street north of Canal Street, 1931“The effect of the elevated—the ‘L’ as New Yorkers generally call it—is to my mind anything but beautiful,” wrote an English traveler named Walter G. Marshall, who visited New York City 1878 and 1879.

“As you sit in a car on the ‘L’ and are being whirled along, you can put your head out of the window and salute a friend who is walking on the street pavement below. In some places, where the streets are narrow, the railway is built right over the ‘sidewalks’…close up against the walls of the houses.”

Second Avenue and 34th Street, 1880s

Second Avenue and 34th Street, 1880sMaybe these unfortunate New Yorkers lived in a tenement before the trains came along, and they couldn’t find alternative housing after the elevated was built beside their building. Or perhaps in the crowded city teeming with newcomers at the time, a flat next to a train was the best they could find with what little they had to spend.

Wrote Marshall: “The 19 hours and more of incessant rumbling day and night from the passing trains; the blocking out of a sufficiency of light from the rooms of houses, close up to which the lines are built; the full, close view passengers on the cars can have into rooms on the second and third floors; the frequent squirting of oil from the engines, sometimes even finding its way into the private rooms of a dwelling-house, when the windows are left open—all these are objections that have been reasonably urged by unfortunate occupants of houses who comfort has been so unjustly molested….”

Allen Street, 1916

Allen Street, 1916Eye-level elevated trains continued into the 20th century, with above ground subway tracks as well as older els making it more likely that New Yorkers could find themselves with a train rattling and shaking their windows.

And it’s still an issue today, of course, even with those original el lines long dismantled. Tenements and apartment buildings near bridge approaches, tunnel entrances, and above ground subway tracks are still at the mercy of mass transit in a city still of narrow streets, single pane windows, and rickety real estate.

Convergence of the Sixth Avenue and Ninth Avenue Els, 1938

Convergence of the Sixth Avenue and Ninth Avenue Els, 1938[Top photo: MCNY x2010.11.2127; second photo: New-York Historical Society; third photo: MCNYx2010.11.4; fourth photo: CUNY Graduate Center Collection; fifth photo: MCNY MNY38078; sixth photo: MCNY MN11786]

The lovely Art Nouveau window grille on a Riverside Drive row house

There’s a lot of enchantment on Riverside Drive, the rare Manhattan avenue that deviates from the 1811 Commissioners Plan that laid out the mostly undeveloped city based on a pretty rigid street grid.

Rather than running straight up and down, Riverside winds along its namesake park, breaking off into slender carriage roads high above the Hudson River. (We have Central Park co-designer Frederick Law Olmsted, who also conceptualized Riverside Park and what was originally called Riverside Avenue, to thank for this.)

But the surviving row house at number 294 deserves a closer look. More precisely, it’s the beautiful wrought iron grille protecting the wide front parlor window that invites our attention.

Number 294 was originally a four-story, single-family home completed in 1901. It’s a wonderful, mostly untouched example of the Beaux-Arts style that was all the rage among the city’s elite at the turn of the last century.

“The most striking features of the facade of 294 Riverside Drive—the orderly, asymmetrical arrangement, the finely carved limestone detailing, the graceful Ionic portico, the slate mansard roof, the elaborate dormers, and the ornate ironwork—eloquently express the richness embodied in the Beaux-Arts style,” wrote the Landmarks Preservation Commission in a 1991 document, which designated the house, built in 1901, as a city landmark.

That unusual front window grille, however, seems to be the one part of the house that aligns more with the Art Nouveau style, which emerged in Europe in the early 1900s and wasn’t widely adopted in New York City.

Take a look at the the graceful, flowing lines and curlicues that mimic flower stems, petals, and other forms found in nature. This grille is original to the house, according to the Landmarks Preservation Commission, which called it “intricate and naturalistic.” The AIA guide to New York City pays homage to its Art Nouveau beauty, calling it “remarkable.”

Why such a fanciful window grille (below on the house in 1939-1941) became part of the house likely has to do with the man who commissioned number 294 and was its first owner.

William Baumgarten, born in Germany and the son of a master cabinetmaker, was one of the most prominent interior designers in Gilded Age New York City. Baumgarten designed the inside of William Henry Vanderbilt’s Fifth Avenue mansion; along with his firm, Herter Brothers, he was responsible for the interiors of other mansions and luxury hotels.

He and his wife, Clara, occupied the Riverside Drive row house until first William and then his wife passed away. In 1914, their survivors family sold it off. It was soon carved up into apartments, as it remains today. (The photo above has a “for rent” sign on the facade, but I just can’t make out a price.)

Baumgarten was known for his creative genius and talent. He would certainly want to live in a row house mansion (now known as the William and Clara Baumgarten House) of his own that reflected the beautiful design touches of his era.

[Third image: NYC Department of Records and Information Services]

November 7, 2021

The understated war memorials inside a private Central Park South club

The New York Athletic Cub on Central Park South might sound like a strange place to honor Veterans Day. But if the doormen let you take a look around this “Italian Renaissance Palazzo style” club founded in 1868, wander through the cavernous lobby.

On the right amid the club chairs and lounge areas is an entire wall with a plaque dedicated to the New York Athletic Club members who served in World War II. Within the plaque is a list of men who make up their “honored dead.”

World War II isn’t the only war worthy of a memorial. Besides the WWII wall are smaller plaques honoring those who died in Korea and Vietnam.

To my knowledge, the Wars in Afghanistan and Iraq don’t have their own monuments inside the building—which opened in 1930 at Seventh Avenue on the former site of the magnificent circa-1880s Navarro Flats, one of the city’s most spectacular apartment complexes.

But there is a plaque commemorating the event that started those wars, listing the names of club members who were killed in the World Trade Center on 9/11.