Esther Crain's Blog, page 2

September 8, 2025

The solemn 9/11 memorial hidden behind the corporate office towers of Sixth Avenue in Midtown

All across metropolitan New York are prominent, powerful monuments honoring those who died in the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001.

Thousands visit the 9/11 Memorial & Museum, where the Twin Towers once stood. A ferry ride away is the Staten Island September 11 Memorial. The Tiles for America installation can be found across the street from the former St. Vincent’s Medical Center, which set up a triage station for the injured 24 years ago this week.

But scattered around are smaller, more personal memorials—like the one honoring the more than 300 victims who worked for Marsh McLennan, a risk-management firm that in 2001 had offices on the 93rd to 100th floors of the North Tower.

It’s in a quiet, peaceful plaza behind the company’s headquarters at 1166 Avenue of the Americas. Step inside this uncrowded public green space off 46th Street and you’ll see a glass wall containing 358 names in small print.

Trees sway behind the glass. A stone bench provides a place to sit and think. When I visited the space was empty, but a bouquet of flowers had been left on the ground.

On the street side of the memorial, the glass wall is flanked by two tower-like hulks of what looks like melted metal. Is the metal from the ruins of the World Trade Center? Other memorials contain pieces of steel from the towers, but I didn’t find anything indicating that Marsh McLennan’s did.

Dedicated in 2004, the memorial doesn’t seem to attract the attention and visitors of the bigger memorials. There’s no overt drama; its power is understated and inconspicuous.

Tracking the 19th century granite milestones that marked the distance from City Hall to Upper Manhattan

If you lived or worked in the Gramercy area in the early decades of the 20th century, you probably passed it by without much thought.

Amid modern transportation infrastructure like traffic lights, lampposts, and street signs stood a faded granite slab embedded in the sidewalk on Third Avenue near 17th Street.

What was this tombstone-like relic? New Yorkers of the era would have known it as one of Manhattan’s last milestones.

Milestones, or mile markers, helped travelers keep track of how many miles they were from City Hall as they traversed the primitive, unlit, often dangerous roads of a sparsely populated city.

Until the urbanization of the bulk of Manhattan Island in the late 19th century, milestones were often the only directionals a horseman or stagecoach driver had as they journeyed up or down one of Manhattan’s few north-south roads.

Taverns popped up around them; owners knew that weary travelers might need a hearty meal and a place to sleep before continuing in or out of the city. These “heirlooms of the past,” as one article called the milestones, were so critical, laws punished those who defaced them.

Mile marker 2, seen in the first three photos in this post, was one of 12 embedded along the Boston Post Road—a former Native American trail that ran from the Battery along the East Side and into the Bronx. Eventually subsumed by the conformity of avenues outlined in the Commissioner’s Plan of 1811, Boston Post Road roughly aligns with today’s Third Avenue.

Milestones also existed on the Bloomingdale Road, the colonial thoroughfare that began at 23rd Street and followed a path through today’s Upper West Side. Unlike the Boston Post Road mile markers, none of the Bloomingdale Road’s markers appear to have survived into the 20th century.

When mile marker 2 was removed from its longtime location on Third Avenue isn’t clear. The first photo, from 1900, reveals a chunk of granite that’s not in bad shape. The second image, from 1931, shows a closeup of a more battered milestone.

By the time the third photo was taken in 1936, it almost looks like trash on the curb waiting to be carted away. Which may have actually happened; the circumstances of its demise isn’t known.

But the fact that it managed to survive into the 1930s is astonishing. I’d attribute it to a combination of the sentimentality some New Yorkers had for ye olde days of Gotham, as well a benign neglect. After outliving its usefulness, most New Yorkers just ignored it.

The two-mile marker’s century-plus lifespan makes me wonder: What happened to the other 11 milestones that dotted Manhattan in today’s Midtown, Yorkville, and Inwood?

According to the City History Club, which in the early 1900s gained guardianship over the remaining mile markers, “some of the milestones have disappeared, while others have had a varied experience.” This includes destruction, theft, removal to a safe private yard, and getting wiped from the cityscape in the interest of “public improvement.”

Tracing the fate of these relics hasn’t been easy. But records and archives give us some information to go on.

In 1904, just three of the original milestones still existed, according to a New York Times article from that year. These included mile marker 2 as well as mile marker 1, which stood in front of 213 Bowery near Rivington Street (fourth photo, from 1897).

Incredibly, the one-mile marker existed at its original Bowery location until 1926, when a truck destroyed it, according to Kevin Walsh writing in Splice Today in 2024. Keeping its memory alive was a 20th century tavern at this location called the One Mile House (see the lettering on the side of the building), visible in the photo below from 1932.

The other mile marker survivor per the Times was at Third Avenue just above 57th Street (possibly in the fifth photo). When and how that one got the boot is a mystery.

Ah, but wait! The Times article didn’t mention the two Boston Post Road mile markers that actually still exist in Manhattan to this day.

One, mile marker 11, originally stood at 189th Street. In 1912, the City History Club moved this weathered artifact to the safety of Roger Morris Park (below), which surrounds the circa-1765 Morris-Jumel Mansion on Jumel Terrace in Washington Heights.

Mile marker 12 is the only milestone still visible on a city street. Its original location was at Hawthorne Street (now 204th Street) near Broadway. Workers building a mansion for wealthy merchant William Isham wanted to trash this relic, but Isham had it preserved as part of a stone gate at the entrance to his estate.

In 1911, Isham’s daughter donated to the city the land her father’s mansion once occupied, intending it to become a public park. That 12th mile marker is still built into the stone entrance that now marks Isham Park in Inwood.

Brooklyn and Queens had mile markers as well. One in Brooklyn remains (or remained? I haven’t seen it lately) on Avenue P and Ocean Parkway. In Bensonhurst, Milestone Park contains a replica of an 18th century milestone that once marked the distance to the ferries to Manhattan and Staten Island.

[Top photo: New York Historical; second photo: MCNY, X2010.11.10060; third photo: MCNY, X2010.11.10059; fourth photo: New York Historical; fifth photo: MCNY, X2010.11.10061; sixth photo: MCNY, 33.173.55; seventh photo: NYC Parks; eighth photo: New York Historical]

September 1, 2025

A two-letter Manhattan phone exchange spotted in Midtown: what does it stand for?

The East Midtown blocks in the shadow of Grand Central Terminal hold some fascinating relics of old New York City.

Case in point is the phone number on this street-facing sign for an elevator emergency alarm at 7 East 43rd Street. “Call ST 6-4300” it reads.

“ST” is another long-obsolete phone exchange, dating back to a pre-1960s city where each neighborhood had a different two-letter designation, often an abbreviation for the area or a reference to a local landmark.

So what was ST? It turns out that the number for this elevator alarm has been found on other buildings around the city; I spotted this one in the Flatiron area in 2016. The exchange would stand for the neighborhood where this company was located.

Stuyvesant Square? Stillwell Avenue? Though two-letter exchanges were phased out more than 50 years ago and dropped from the yellow pages in 1978, someone must know.

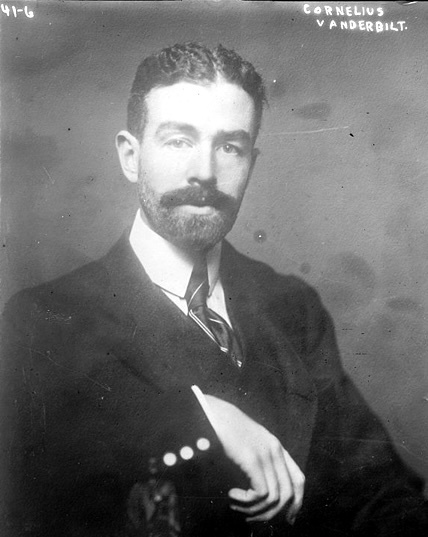

A disappointment to his family, this Gilded Age Vanderbilt heir ended his life in a Broadway hotel

Of all the prominent families who took front and center in Gilded Age New York City, few dominated both the business and society realms like the Vanderbilts.

Among the family members making headlines in the late 19th century were patriarch Cornelius “Commodore” Vanderbilt, who built his fortune in shipping and railroads. At the time of his death in 1877 he was the richest man in America.

His son William “Billy” Vanderbilt inherited his father’s business and made his own name as a passionate art collector. He also built and resided in the Vanderbilt “triple palace” mansion at Fifth Avenue and 51st Street.

Then there’s social-climbing Alva Vanderbilt, wife of Billy’s son W.K. “Willy K” Vanderbilt. Alva was the hostess of the spectacular 1883 “fancy dress” ball held in her Fifth Avenue chateau that finally gave her entry into elite New York society.

But amid these high-achieving Vanderbilts were family members who stayed under the radar, either because they didn’t court controversy or they were deemed to be family embarrassments. One of the latter was Cornelius “Corneel” Jeremiah Vanderbilt.

Born on Staten Island in 1830, Corneel was the second son of Commodore Vanderbilt. He was bright but also “confrontational and aggressive, particularly in relations with his father,” wrote Wyn Derbyshire in his 2009 book, Six Tycoons.

Tall, gangly, and not particularly handsome, Corneel proved to be a disappointment to his father. But it should be noted that the Commodore was also disappointed in his heir apparent Billy, who he thought of as clumsy and of low intelligence.

The Commodore had contempt for Corneel because “he suffered from epilepsy from the age of 18, a malady which the Commodore regarded as a sure sign of weakness,” wrote Derbyshire. He also deemed it a sign of “mental derangement” and had Corneel committed to the Bloomingdale Insane Asylum (above)—one of several commitments his father orchestrated.

“He’s a very smart fellow, but he’s got a cog out,” the Commodore would tell friends, according to Arthur T. Vanderbilt’s book, Fortune’s Children. “I’d give a hundred dollars if he’d never been named Corneel.”

After Corneel left the asylum, his father set him up with an allowance of $100 a month, convinced he’d never be able to support himself and unwilling to have him work in the family business.

Corneel began hustling money (particularly from his friend, publisher Horace Greeley), gambling, and trading on the Vanderbilt name. He left town for Hartford, Connecticut because his father bought him a fruit farm there, hoping he’d never have to see him again, per Fortune’s Children.

At 25, he married Ellen Williams (above), the daughter of a Hartford minister. It made his father very happy.

Still, Corneel “continued living well beyond his means, frequenting gambling dens and brothels in Manhattan, borrowing money from professional gamblers, assigning his allowance as security, writing bad checks, landing in debtors’ prison on a number of occasions and depending on his mother to bail him out….” according to Fortune’s Children.

In 1868, Corneel was forced to file for bankruptcy. His mother died that same year, and Ellen passed away in 1872. He sold the fruit farm and began keeping company with George Terry, “an unmarried hotel keeper whom Corneel considered ‘my dearest friend,'” wrote T.J. Stiles in his book, The First Tycoon.

Corneel and Terry (in photo above) met years earlier when Terry was the proprietor of the United States Hotel on Pearl and Fulton Streets. Terry often visited Corneel and Ellen’s home in Hartford, according to a New York Daily Herald article from 1878.

The exact nature of their relationship isn’t known. Though Corneel addressed one letter with “my darling George,” according to Stiles, it wasn’t unusual at the time for platonic male friends to make such declarations. “The intensity of their relationship raises the question of precisely how intimate they were,” wrote Stiles.

After the Commodore passed away, Corneel discovered that his father left the bulk of his fortune to Billy. Following a legal challenge, Billy ended up paying his brother off to drop his suit. Cornell and Terry then embarked on a six-month trip around the world, noted a New York Times announcement in 1880.

His domineering father was out of his life, and Corneel was able to buy back the fruit farm and commission the building of a 30-room mansion on the property (above). Yet he was still troubled. In his 1888 book 28 Years in Wall Street, financier Henry Clews described a meeting with Corneel during a warm afternoon drive in Long Branch, New Jersey.

“He spoke feelingly about his wasted life, and concerning the many good friends who had come so often to his rescue, and had got him out of his numerous holes, into which, through misfortune, he had been thrown,” wrote Clews.

His “wasted” life would soon come to a tragic end. In March 1882, Corneel and Terry checked into the Glenham Hotel (above) on Broadway and 22nd Street. The two had returned to New York after a trip to Hot Springs, Arkansas, where Corneel sought relief from his epilepsy and other ailments.

Still at the Glenham in April, Terry heard the firing of a pistol and rushed to his companion’s bedside. Corneel had shot himself in the temple. He died four hours later at the age of 51.

When news of Corneel’s suicide hit the papers the next day, reporters made his estrangement from his father and his inability to follow in the Commodore’s powerful footsteps a main theme.

In a New York Times article, the reporter called Corneel the “discarded son of the late Commodore Vanderbilt.” Sadly, it’s a fitting description.

[First image: Wikipedia; second image: We-Ha.com; third image: Wikipedia; fourth image: We-Ha.com; fifth image: Connecticut Museum of Culture and History; sixth image: Wikipedia; eighth image: Findagrave.com]

August 31, 2025

A giant faded ad on an Upper Manhattan tenement is a remnant of a holdout family business

Tucky the squirrel never became a renowned company animal mascot like the GEICO gecko or the Playboy bunny.

But there he is in a four-story faded ad on the side of a tenement at 161st Street and Broadway. He’s pushing a cartload of stuff, presumably to a storage unit at Tuck-It-Away, a self-storage facility once located 30 blocks south on 131st Street and Broadway.

I’m guessing the ad went up in the 1980s, considering that the phone number for the facility doesn’t have an old-school two-letter prefix. Indeed, Tuck-It-Away was founded in 1980, one of many unglamorous but vital companies that used to do business on Manhattan’s margins.

For Tuck-It-Away, that meant an orange and black brick building in the West Harlem neighborhood of Manhattanville. The company eventually expanded to five storage facilities and was taken over by the original owner’s son in 1990, according to a 2008 New York Times article.

The faded ad remains on the side of the tenement, but Tuck-It-Away is history. In the 2000s, the 131st Street warehouse found itself standing in the way of Columbia University’s plan to build an expansive modern campus in Manhattanville.

After a long battle to stay in its longtime location—including a legal fight that went all the way to the New York State Court of Appeals—Tuck-It-Away gave in to Columbia and ended up with a reported $34 million settlement.

Columbia built its campus, and for the time being, Tucky lives on.

[H/T to JS for spotting the faded ad and the second photo]

August 25, 2025

An East Village restaurant’s ghost sign is a relic of the neighborhood’s Italian immigrant past

By the time Sicilian immigrant Michael Lanza founded his namesake restaurant in 1904, the location he chose on First Avenue between 10th and 11th Streets was shaping into a mini Little Italy.

Across the Avenue on 11th Street was Veniero’s, the Italian bakery dating back to 1894. in 1908, specialty grocers Russo’s would open a few doors down. John’s red sauce joint got its start on East 12th Street also in 1908, and De Robertis Pastry Shoppe launched in 1904 steps away.

Mary Help of Christians Church, completed in 1917, catered to Italian Americans. The Italian Labor Center up the way on 14th Street served as headquarters for the cloakmakers’ union beginning in 1919.

The church met the wrecking ball in the 2010s, and De Robertis shut its doors in 2014. As the East Village’s immigrant population dwindled, so did the dozens of ordinary Italian American businesses: barber shops, funeral homes, bars, and groceries. (Above, Lanza’s in 1940)

Since 2016, Lanza’s has been gone too. But a remnant of this red sauce favorite of locals (and mobsters from the Gambino and Bonanno familes, per Village Preservation) still exists.

Its original stained-glass sign still graces the entrance to 168 First Avenue, which is now home to Joe & Pat’s, a pizzeria. Joe & Pat’s also kept Lanza’s tile floor at the entrance, as well as the kitschy oil paintings of Italian cities hanging above the tables inside.

Joe & Pat’s is also an Italian immigrant business, started by two brothers who arrived on Staten Island in 1958 and opened their pizzeria in 1960.

Keeping the Lanza brand in their East Village outpost had to be intentional—an homage to a legendary restaurant and maybe to the immigrant enclave that helped sustain it.

[Second image: NYC Department of Records and Information Services]

This Upper East Side Russian Orthodox cathedral has dramatic beauty—and a dramatic backstory

Slender, inconspicuous East 97th Street is the last place you would expect to come across a cathedral with breathtaking onion domes crowned by gilt crosses.

.But take a walk between Madison and Fifth Avenues, and you’ll find yourself face to face with St. Nicholas Russian Orthodox Cathedral.

It’s a spectacular Baroque beauty of red brick, gray stone, limestone trim, and cherub faces carved into rooftop pendant arches. The facade is opulent and glorious—and unique. It’s the only example of Moscow Baroque in New York City and possibly the sole example in all of America.

What exactly defines Moscow Baroque? Like the Baroque style of Western Europe that came into vogue in the 16th and 17th centuries, it’s exaggerated and bold, with dynamic curves, grand decorative elements, and domes and cupolas that reach toward the heavens.

Moscow Baroque, which emerged in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, combined these characteristics with more traditional Russian architecture.

The interior of the cathedral also reflects the Baroque aesthetic, with frescoes on the walls and ceiling, gilded surfaces, rich colors, and theatrical lighting.

Sunlight illuminates the sanctuary through stained-glass windows. It’s a space like no other in New York, and it feels much larger than the 900-seat cathedral it actually is.

Such a dramatic cathedral inside and out also has a fittingly dramatic backstory driven by the political upheaval in Russia in the 20th century.

Completed in 1902, it was the home church of the congregation of St. Nicholas, founded in the 1890s by immigrants from the Russian empire. By 1899, the congregation had 300 members and was too large for its rented rooms at 323 Second Avenue near Stuyvesant Square.

Low funds drove the decision to relocate to Carnegie Hill. “The congregation chose an inexpensive uptown location at 97th Street off Fifth Avenue, in an area that was beginning to emerge as a neighborhood of modest flats,” wrote Christopher Gray in a 2000 New York Times Streetscapes column.

Czar Nicholas II donated the first rubles to construct the new church, stated David W. Dunlap, author of From Abyssinian to Zion: a Guide to Manhattan’s Houses of Worship. Two years after it opened in 1904, a New York Times reporter observing the consecration of a new solid oak, Russia-made altar wrote up his impressions.

“The air was heavy with perfume, and the multitude of sacred candles shedding a dim light throughout the church combined with the solemn chant of choristers and the psalm singers to produce a quaint splendor seldom surpassed in this city,” stated the reporter.

In 1905, the Russian Orthodox Church made St. Nicholas its official American headquarters, designating the church a cathedral, wrote Gray.

But events in Russia had an effect on the congregation. Czar Nicholas II abdicated his throne in 1917 and was executed with his family the next year. The Russian revolution was in full swing.

“After the Communists came to power they began remaking the Russian church to fit the goals of an atheist state,” wrote Gray. “Priests and bishops were persecuted and fled Russia, replaced by clerics who were willing to accommodate themselves to the party line.”

In 1920, Bolshevik sympathizers came to St. Nicholas and disrupted a communion service, “but were thrown out by the faithful,” wrote Gray. They weren’t the only ones tossed from the sanctuary.

A Moscow-appointed religious leader was sent to take over the cathedral in 1923, but he was “carried out of the building and down the steps onto 97th Street, kicking and screaming,” stated Gray.

“In the following decades St. Nicholas had an uneasy time as the official church of an officially atheistic country that was to many Americans the enemy of the United States,” he added.

That uneasy time included an ongoing lawsuit over the control and ownership of the cathedral, which the U.S. Supreme Court gave to the Moscow-backed leadership in a 1952 ruling, per Dunlap.

With the Soviet Union long dissolved, the struggle for church control seems to have taken a back seat to the struggle of fundraising. St. Nicholas has been a New York City landmark since 1973, and a major restoration took place in the early 2000s.

The Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) report includes an appropriate passage from a Russian Orthodox publication. The passage appears to be from the cathedral’s early days, but it describes today’s St. Nicholas perfectly.

“Standing as it is, among the tall apartment buildings of routine style, it strikes one like a ray of sun on a cloudy day,” per the LPC report. “It’s graceful and creative facade attracts and fascinates the eye.”

August 18, 2025

Meet the miniaturist who painted exquisite portraits of the Gilded Age’s best-known characters

New York’s Gilded Age was an era defined by bigness. Townhouses were replaced by mansions. Dry goods emporiums dominated Broadway. Comically proportioned bustles exaggerated a woman’s silhouette.

One exception, however, was the miniature. Popular throughout history, these tiny painted portraits experienced a resurgence in the late 19th century among elites, particularly women. They would display them in a parlor cabinet, for example, or wear one as a piece of jewelry.

Portrait photography had become an accessible medium by the late 19th century, which perhaps made miniatures more prized. But paintings also provided “realistic coloring of the subjects’ faces and a vitality that was missing in black and white photos,” wrote Kathleen Langone in her book The Miniature Painter Revealed: Amalia Küssner’s Gilded Age Pursuit of Fame and Fortune.

It was an ideal time to be a miniature painter—and a talented Midwestern native with a knack for self-promotion took advantage of the opportunity.

Born in 1863 in Indiana to a German immigrant family, Amalia Küssner (top image) showed an early talent for drawing. After a stint at a finishing school in New York City, she returned to Indiana to launch an art studio specializing in watercolor miniatures.

But like so many artists, she wanted a larger life than the Midwest offered, and that meant a move to New York City in 1891. She spent a year working for Tiffany’s, then began racking up hefty commissions for painting some of Gotham’s wealthiest and most notable women.

Those included actress Lillian Russell, Emily Havemeyer (of the sugar-refining Havemeyers), Alva Vanderbilt Belmont (at left), and Caroline Astor, the doyenne of the city’s social world.

What made Küssner so popular? An Indiana classmate connected her to Gilded Age society figures when she first relocated to New York. Yet she also benefited from the way she posed women.

“She became known for her wrap style, where many of these ladies wore swaths of fabric like tulle, velvet, or satin, and often layered on top with lace or silk flowers,” noted Langone on the Her Half of History podcast.

Küssner painted her subjects in gemstone jewelry, which made them look regal. This no doubt flattered the women who posed for her, who liked to think of themselves as New York royalty.

She also was adept at the Gilded Age version of airbrushing by painting subjects “in semi-darkness to accent their facial features, while she would sit by a window with natural light,” stated Langone.

And Küssner proved to be canny about self-promotion. “In New York, she knew that she had to dress above her station, as they would say,” said Langone in an interview with Artnet. “She took every penny she had to dress as elegantly as she could. As she got more money, she would buy gowns from House of Worth.”

Her fame—particularly as a young female artist in an art world dominated by men—landed her in New York City newspapers. Reporters wrote about Küssner’s trip to England in 1896, “where, apparently, she is duplicating her New-York success,” stated the New York Times that year.

The trip to the UK was orchestrated by New York-born socialite Minnie Paget, who arranged for Küssner to paint miniatures of British royal figures as well as Consuelo Vanderbilt, daughter of Alva Vanderbilt Belmont and now the unhappily married Duchess of Marlborough (fourth image).

Through the end of the 19th century, Küssner would travel the world to paint the Prince of Wales, Czar Nicholas II and his wife, and mining magnate Cecil Rhodes. (Above left, an 1894 miniature of Matilda Thora Wainwright Scott Strong, a Pennsylvania heiress.)

She would marry into the elite world she painted, with a 1900 wedding at St. Patrick’s Cathedral to lawyer Charles duPont Coudert. Her husband’s family felt she didn’t have right the society credentials. But they did gift the couple a house at 53 West 48th Street, per the Brooklyn Times Union.

After her marriage, Küssner (above, in 1899) and her husband journeyed to Europe and the UK, and they spent most of the rest of their lives abroad. She continued to paint miniatures, but the Gilded Age was ending, and her fame was fading.

When she died in Switzerland in 1932, it was the Indiana newspapers, not the New York media, that took note and recounted her extraordinary life and career.

[Top photo: Wikipedia; second image: LOC; third image: newportalri.org; fourth image: the World; fifth image: Wikipedia; sixth image: sketch of Amalia Küssner by Violet Granby, 1899, via Artnet]

Meet the miniaturist who painted exquisite portraits of the Gilded Age’s best-known faces

New York’s Gilded Age was an era defined by bigness. Townhouses were replaced by mansions. Dry goods emporiums dominated Broadway. Comically proportioned bustles exaggerated a woman’s silhouette.

One exception, however, was the miniature. Popular throughout history, these tiny painted portraits experienced a resurgence in the late 19th century among elites, particularly women. They would display them in a parlor cabinet, for example, or wear one as a piece of jewelry.

Portrait photography had become an accessible medium by the mid-19th century, which perhaps made miniatures more prized. But paintings also provided “realistic coloring of the subjects’ faces and a vitality that was missing in black and white photos,” wrote Kathleen Langone in her book The Miniature Painter Revealed: Amalia Küssner’s Gilded Age Pursuit of Fame and Fortune.

It was an ideal time to be a miniature painter—and a talented Midwestern native with a knack for self-promotion took advantage of the opportunity.

Born in 1863 in Indiana to a German immigrant family, Amalia Küssner showed an early talent for drawing. After a stint at a finishing school in New York City, she returned to Indiana to launch an art studio specializing in watercolor miniatures.

But like so many artists, she wanted more, and that meant a move to New York City in 1891. She spent a few years working for Tiffany’s, then began racking up hefty commissions from some of Gotham’s wealthiest and most notable women. Those included actress Lillian Russell, Emily Havemeyer (of the sugar-refining Havemeyers), and Caroline Astor, the doyenne of the city’s social world.

What made Küssner so popular? A finishing-school connection to Gilded Age society helped initially. Yet she also benefited from the way she posed women. “She became known for her wrap style, where many of these ladies were swaths of fabric like tulle, velvet, or satin, and often layered on top with lace or silk flowers,” noted Langone on the Her Half of History podcast.

Küssner painted her subjects’ jewelry, making them look regal—which no doubt flattered the women who posed for her, who liked to think of themselves as New York royalty.

She also was adept at the Gilded Age version of airbrushing by painting subjects “in semi-darkness to accent their facial features, while she would sit by a window with natural light,” stated Langone.

And Küssner proved to be canny about self-promotion. “In New York, she knew that she had to dress above her station, as they would say,” said Langone in an interview with Artnet. “She took every penny she had to dress as elegantly as she could. As she got more money, she would buy gowns from House of Worth.”

Her fame—particularly as a young female artist in an art world dominated by men—landed her in New York City newspapers. Reporters wrote about Küssner’s trip to England in 1896, “where, apparently, she is duplicating her New-York success,” stated the New York Times that year.

The trip to the UK was orchestrated by New York-born socialite Minnie Paget, who arranged for Küssner to paint miniatures of British royal figures as well as Consuelo Vanderbilt, daughter of Alva Vanderbilt and now the unhappily married Duchess of Marlborough (third image).

Through the end of the 19th century, Küssner would travel the world to paint the Prince of Wales, Czar Nicholas II and his wife, and mining magnate Cecil Rhodes. (Above left, an 1894 miniature of Matilda Thora Wainwright Scott Strong, a Pennsylvania heiress.)

She would marry into the elite world she painted, with a 1900 wedding at St. Patrick’s Cathedral to lawyer Charles duPont Coudert. Her husband’s family felt she didn’t have right the society credentials, but they did gift the couple a house at 53 West 48th Street, per the Brooklyn Times Union.

After her marriage, Küssner (above, in 1899) and her husband journeyed to Europe and the UK, and they spent most of the rest of their lives abroad. She continued to paint miniatures, but the Gilded Age was ending, and her fame was fading.

When she died in Switzerland in 1932, it was the Indiana newspapers, not the New York media, that took note and recounted her extraordinary life and career.

[Top photo: Wikipedia; second image: LOC; third image: the World; fourth image: Wikipedia; fifth image: sketch of Amalia Küssner by Violet Granby, 1899, via Artnet]

August 17, 2025

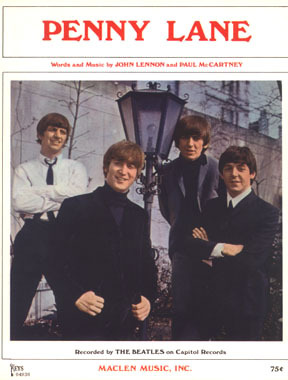

Take a walk through the Beatles-inspired co-op on 24th Street that built a Liverpool Street in its lobby

If you were asked to name a New York City building closely associated with The Beatles, the Dakota would likely come to mind first.

Perhaps you’d also think of the Plaza Hotel, where the fab four holed up on their first trip across the pond in February 1964. Or John Lennon’s East 52nd Street penthouse, where he lived with May Pang during his “lost weekend” in the mid-1970s.

But there’s another Beatles building on East 24th Street. No, none of the band members ever resided in this former J.M. Horton’s ice cream factory, which sits in the middle of a Gramercy side street of tenements and small stores.

The Beatles theme came from the 1970s developers of this factory-turned-apartment house. The developers were so Beatles-obsessed, the ground floor interior was renovated into an ode to the lads from Liverpool, according to a recent New York Post article.

Instead of a typical staid lobby setup, residents and visitors pass through a lobby that evokes a charming Liverpool-like street—complete with cast-iron street lamps, a terrace with chairs and a table, and Tudor details like brick and dark wood beams.

The building, at 215 East 24th Street, includes other British and Beatles-related touches.

The lobby doors of the ground-floor apartments are styled to look like the front doors of homes and shops you might encounter on a UK street, with multi-pane glass, shingled awnings, and fanlights.

The name of the building? The Penny Lane, of course. It’s an homage to the sunny song the band released in 1967. (Unfortunately there’s no architectural nod to the barber shop referenced in the lyrics.)

The Horton Ice Cream company was to ice cream what the Beatles were to popular music. Founded in 1865 by New Yorker James Madison Horton, the brand opened retail outlets across the city. (One ghost sign for a former Horton’s can still be seen on a Columbus Avenue walkup.)

By the late 19th century, Horton’s produced 3 million gallons of the sweet stuff per year, according to a 2015 article in West Side Rag. But facing heavy ice cream competition through the decades, the brand disappeared in the 1960s. The East 24th Street plant was vacated by the early 1970s.

In 1975, a renovation of the factory into apartment residences by the Conthur Development Company was announced. The 179-unit, seven-story building opened soon after, with many generously proportioned apartments that took into account the high ceilings of the former factory.

The decision to give the building a quirky Beatles theme isn’t referenced in any of the 1970s articles about the co-op’s beginnings. And the person or people who came up with the Liverpool lobby idea are unknown.

There’s another mystery attached to the Penny Lane. The building was completed with an attached parking garage. The Beatles-fanatic developers commissioned a mural featuring 12 Beatles album covers to be painted inside the garage.

The garage underwent a renovation, and sometime after 2007, the mural disappeared. Was it painted over—or stored for safekeeping? New York City Beatles fans would love to know.

[Third image: Beatlesebooks.com]