Esther Crain's Blog, page 5

June 22, 2025

This image from the 1870s of a sparse, country-like Riverside Drive is older than the Drive itself

Riverside Drive didn’t officially open until 1880. But the planning of what was then called Riverside Avenue began in the mid-1860s, when a scenic boulevard was proposed alongside a new public park yet to be built beside the Hudson River.

That park—today’s Riverside Park—began opening in the 1870s. By September 1879, the beginning of Riverside Avenue at 72nd Street was laid out, paved, and graded—and an unknown photographer decided to take a photograph.

It’s not the clearest scene, and it helps to click into the image and enlarge it. On the right is a sidewalk, a nice addition for the pedestrians expected to enjoy the Drive as a place for parade-watching and promenading.

A white picket fence surrounds the house on the corner, which looks like a simple wood frame dwelling similar to the other wood houses that dotted the West Side in the early Gilded Age. The posh Beaux-Arts townhouses on this corner today wouldn’t come for another two decades, when the Drive rivaled Fifth Avenue as Manhattan’s millionaire mile.

On the left is a low curved stone wall, likely marking the entrance to Riverside Park; it’s similar to the stone wall on the site today. Trees flank both sides of the Drive, and what seems like part of a wagon wheel can be seen on the far left, peeking into the frame.

The figure in the middle appears to be a man with a photography tripod. But it’s actually supervising engineer William J. McAlpine, a New York-born civil engineer who oversaw the “Riverside Contract,” per an 1878 New York Times article.

The photo, dated 1879 and part of the Digital Collections of the New York Public Library, is a rare visual record of Riverside Drive on the cusp of becoming one of the Gilded Age city’s most sought-after residential addresses—before the mansions, townhouses, statues, and memorials.

That Riverside Drive, seen in a 1934 NYPL photo (second image) looking down the Drive to 72nd Street, is the one most of us know today, though mansions and townhouses gave way to apartment buildings.

In the 1870s it was still an unfinished street cutting through what was once farmland and estate grounds—overlooking a sliver of a park that held promise and possibilities. (Above, an image of the built-up Drive from 74th street in 1910)

Curious about Riverside Drive’s early days and its development into one of New York’s most beautiful streets? Join Ephemeral New York on a Gilded Age-themed walking tour of the Drive from 83rd to 107th Streets on Sunday, June 29 or Sunday, July 20 that takes a look at the mansions and monuments of this legendary thoroughfare.

[Third image: History101.nyc]

June 16, 2025

Unloved when it opened in 1958, a Greenwich Village “superblock” apartment complex is finally embraced

The first announcement about the monstrous apartment “superblocks” came from the New York Times in July 1957. “Six-Block Project to Rise in Village,” the headline read.

The description that followed sounded like a housing plan better suited for an outer borough, not the historic loveliness and charm of low-rise Greenwich Village.

“Three buildings of 17 stories each will provide a total of 2,004 apartments in the rectangle bounded by West Third Street, Mercer Street, West Houston Street, and West Broadway (which will be widened to 120 feet and renamed Fifth Avenue South),” wrote the Times.

“Each building will be nearly three-blocks long, faced with glazed brick in wide vertical panels of blue, yellow, lavander, and other colors.” The buildings would frame an underground garage, per the Times, and feature a park and play areas. A two-room unit would run $120 per month.

Ultimately, four buildings forming two “superblocks” spanning Mercer Street to LaGuardia Place and West Third to Bleecker Street were constructed.

The land was acquired (and then sold to developers after dozens of tenements and manufacturing buildings were razed) by Parks Commissioner Robert Moses under a slum clearance effort, according to a 2012 Village Preservation blog post.

The renaming of West Broadway never materialized. But the behemoth christened Washington Square Village opened to tenants in 1958—a for-profit venture aimed at middle class residents.

Unsurprisingly, this unglamorous project was met with jeers.

“The mellow old landmarks of Greenwich Village are rapidly disappearing beneath modern glass monuments to the bourgeois respectability against which the Bohemians revolted forty years ago,” wrote one critic in 1957 in the New York Times.”This so-called Washington Square Village will hardly resemble the Washington Square of Henry James’ day or the Greenwich Village of Maxwell Bodenheim’s.”

A group called the Greenwich Village Association charged that apartment projects like Washington Square Village, “’failed to meet basic community needs’ and brought into the area ‘large numbers of people with no reason for neighborhood pride,'” the Times reported in April 1959.

And in a 1958 Times article about the demise of the Village, another writer had this to say: “One block south of the Square, these modern towers—they are striped blue, pumpkin, yellow and white—stand like a Leger painting next to a Victorian etching.”

The critics might have been pleased when Washington Square Village’s developers became insolvent in 1963. New York University swooped in to purchase the complex for $25 million, announcing that current leaseholders could remain but as vacancies opened up, professors would take over the apartments.

As time passed, the Village adjusted to Washington Square Village. Sasaki Garden, designed by Modernist landscape architect Hideo Sasaki, provided a public oasis of trees amid pathways and benches. A playground gave resident kids a place to run. The colorful glazed bricks made a nice contrast to the boring white-brick postwar apartment house.

And after all, Washington Square Village provided modern, doorman-attended apartments for people and families (mostly NYU-affiliated as time went on) who would have a hard time finding comparable and affordable housing in the increasingly posh Village.

It may have taken half a century, but in 2011, Washington Square Village finally got its due. That year, the New York State Historic Preservation Office agreed with the Landmarks Preservation Commission’s earlier finding that the complex should be named to the National Register of Historic Places.

Washington Square Village was deemed to be “a superblock complex of two residential towers, elevated landscaped plaza, commercial strip, and below-grade parking” and “an impressive example of postwar urban renewal planning and design,” the Office wrote, via a 2016 Village Preservation post.

The historic eligibility just goes to show that if a derided building waits it out long enough, the neighborhood just might come around and embrace it.

[Top image: Wikipedia; second image: William Eppes Collection, GVSHP; third photo: Robert Otter via Wikipedia]

June 15, 2025

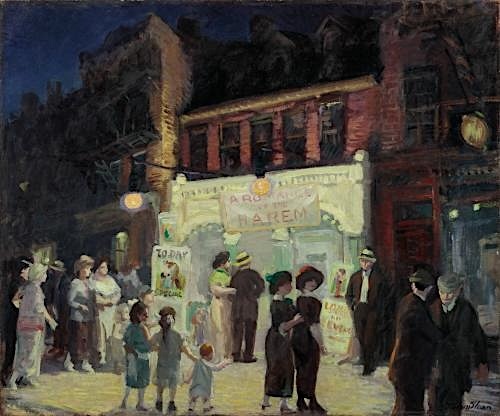

John Sloan captures the sidewalk drama outside a long-gone Carmine Street movie theater

“Out for a walk down to Bleecker and Carmine Streets, where I think I have soaked in something to paint,” wrote Ashcan school artist John Sloan in his diary on January 25, 1912.

Like so many New Yorkers, Sloan was a walker of city streets, observing and absorbing the physical and atmospheric changes from neighborhood to neighborhood. Though his life and work are now synonymous with early 20th century Greenwich Village, at the time of this diary entry he and his wife were living in Chelsea.

Perhaps Sloan found himself at Bleecker and Carmine Streets while scouting out the area adjacent to his future studio at Sixth Avenue and Cornelia Street. He and his wife also found an apartment on Perry Street later that year.

But what made him decide to paint this scene outside the Carmen Theater is a mystery—except that it captures the kind of beauty and drama in the ordinary that Sloan made his signature.

A year after completing “Carmine Theater,” Sloan revisited Bleecker and Carmine Streets and made the theater his subject in 1913’s “Movies.” This time, rather than a shuttered theater, a group of kids, and a disapproving nun, there’s a nighttime crowd and cinematic magic in the air.

The show outside the theater is the focus here. The feature on the marquee, “A Romance in the Harem” promises “lurid entertainment and capitalizes on the ‘Orientalism’ craze—Western fascination with exotic Eastern cultures,” explains the Toledo Museum of Art, which has this painting in its collection.

The Carmine Theater is ablaze in light, and the allure of moving pictures brought out the neighborhood’s young, old, coupled, and alone. “Film itself was still an exotic spectacle,” continued the museum caption. “Just like in the silent films of the day, the interplay of glances between the people in the painting engages the viewer and establishes drama.”

Carmine Street in the early 1900s was part of a crowded Italian immigrant neighborhood, and the Carmine Theater, opened in 1914, might have been a curious addition amid the old houses, shabby tenements, and horse-drawn pushcarts.

The Carmine showed its last film in 1925, according to WestView News, wiped off the cityscape thanks to the extension of Sixth Avenue and a remaking of the area street grid.

I tried to find a photo of the theater before its demolition, and it might be this building second from right, now with a larger marquee advertising a film starring , a popular child actor of the teens. (Click the image to see a larger view.)

Replacing the Carmine Theater in 1928 was the new home of Our Lady of Pompeii Church—a beacon in the almost totally vanished Little Italy that captured John Sloan’s imagination for two moments in time.

[Third image: NYPL Digital Collections]

June 9, 2025

A black and white etching of a 1940s street corner captures New York’s menacing film noir feel

Born in Australia in 1881, Martin Lewis studied art in New Zealand and Sidney, then settled in New York City in the 1910s as a commercial artist.

But a trip to Japan in the 1920s changed his artistic direction to printmaking. “At first he worked from his Japanese sketchbooks but soon turned to scenes from American urban life,” states New Hampshire’s Currier Museum of Art.

Over the next few decades, Lewis made prints of his drypoint etchings that captured the rhythms of Gotham’s sidewalks and streets, from snow-covered brownstone stoops to shadowy corners under elevated trains to young women on the town to morning commuters hurrying to work.

“Chance Encounter,” from 1941, is a seductive dance of light and darkness. “Standing on the sidewalk in front of an old-fashioned storefront, a teenaged boy and girl lock gazes,” states the caption to this etching by the Currier Museum.

“Hands in his pockets, the boy smiles and speaks as his bobby-sox counterpart assumes a coquettish pose. Pronounced chiaroscuro (contrast of light and shadow) heightens the tension of the moment while inside the store window, pulp magazines entitled True Love and G-Man suggest romance and excitement.”

“Farther up the street, an older couple chats idly together, their sedate familiarity with one another forming an effective foil to the self-consciousness of the teens in the foreground.”

Is it an image of innocent teenage flirtation and posturing in the months before World War II, or something more menacing? It’s impossible to know what Lewis had in mind.

But the film noir atmosphere seems to tell us that something potentially dangerous is in the air at this nighttime meetup, and the possibility makes the print riveting and provocative.

[Print: Artsy]

This Gilded Age holdout house still stands because the widow who owned it said no to developers

Is West End Avenue the holdout capital of Manhattan? Peeking out between many blocks of stately prewar apartment buildings are several lone Gilded Age row houses that managed to evade the bulldozer.

Some are restored and lovely, others shabby chic. All have backstories. But a strong-willed widow steeled by a tragic family drama may have been the reason the slender row house at 249 West End Avenue, just south of 72nd Street (above), is still standing.

First, let’s dial back to 1893. That’s when No. 249 got its start as a new and fashionable middle house in a group of five elegant attached homes (below advertisement).

Romanesque Revival in style, the three middle row houses had bow fronts and terraces in front of the rounded windows on the third floor. The two outer dwellings stood like handsome sentries framing the inside three. All had unusual small porthole-like windows on the fifth floor.

The row was designed by Clarence True, an architect and builder who brought his fanciful architectural vision to West End Avenue and Riverside Drive in the 1890s, just as development was ramping up on these recently opened streets.

True liked building clusters of delightful row houses that rebelled against the staid and uniform brownstones of the 1860s and 1870s. Through the early 20th century he put up hundreds of these eclectic dwellings in the area, which were in high demand by well-heeled buyers.

His row houses became defining features of Manhattan’s newly elite West End neighborhood—today known as the Upper West Side.

Ferdinand Huntting Cook and his wife, Mary Aldrich Cook, weren’t the first residents of No. 249. After the house was built, it was owned by a man named William Nesbit. Joseph Powell, a cigar manufacturer, was the next owner; he died of pneumonia there.

At some point after Powell’s death, the Cooks bought the row house, turning it into a family home for themselves and their five children. It was a convenient location for the two boys in the household, who attended nearby Collegiate school.

Sadly, all was not well with Ferdinand Cook. A descendant of an old and wealthy New York City family, Cook was employed by the Department of Parks and had dabbled in other businesses. In 1913 he was 50 years old and later described by his brother Henry Cook as “ill and depressed.”

Exactly what troubled Ferdinand Cook isn’t known. But his depression led to a tragedy that began on January 3, 1913, when he told Mary he was heading out to Park & Tilford’s, a high-end grocery and liquor store on 72nd Street and Columbus Avenue . . . and never returned.

Mary was understandably concerned. She alerted the police and hospitals, thinking he may have been hurt in a windstorm the night he disappeared. Newspapers covered the story, interviewing family members. “It is possible that he suffered an attack of amnesia and wandered off,” Henry Cook told a reporter from the New York Times. “We have no clue.”

As the days went by, Mary became “worn out and ill from worry over his absence,” per the Times. Descriptions of Ferdinand Cook noting his “iron-gray hair,” that he weighed about 150 pounds, wore two rings and a gold watch, and “did not have more than $18 in his pockets.”

A month later, her husband’s body was found in a wooded area in Queens. By his side was a gun; he apparently shot himself in the temple. After learning the news, Mary Cook “was in a hysterical condition,” wrote one Brooklyn newspaper.

If Mary ever spoke of her heartbreak and pain, her words were not recorded in any newspaper account. Apparently, life went on for this 43-year-old widow. Through the 1920s, the engagements of two daughters and a son were announced. The brides held their wedding ceremonies at All Angels’ Church on West End Avenue and 80th Street.

Her children were grown, and her neighborhood was also changing. The lovely row houses Clarence True and other developers had built were being marked for demolition, sold to make way for a new kind of New York housing: the tall apartment residence.

Mary “repeatedly declined offers to sell the house, even as similar homes to the north and south were demolished for construction of large-scale apartment buildings,” according to the West End-Collegiate Historic District Extension Report.

The first offer to sell may have come just a few years after her husband’s suicide, as the building to the north, 255 West End Avenue, was completed in 1917. On the south side, development of 243 West End Avenue was underway in the early 1920s.

It stands to reason that developers of both buildings offered Mary money to vacate—money that the owners of the four neighboring row houses took. For reasons only she knows, Mary held on to the home were she mourned her husband and raised her family.

After Mary Cook died in 1932, the holdout house—smushed between two giants and useless to developers—changed hands again. “During the 1930s, and possibly extending into the 1940s, the Continental Club was located within the building, offering lectures, musical performances, and other cultural events,” notes the Historic District Report.

Inside the Continental Club was also the Uptown Gallery, “where works of cutting-edge artists including Adolph Gottlieb and Mark Rothko were shown.”

No. 249 returned to residential use in the 1950s and was eventually converted into apartments. Recently it was covered in scaffolding, some of which remains on the first floor, blocking it from street view.

But you don’t need to see the front entrance to recognize what a jewel this row house is. Thanks to decisions made by Mary Cook, developers were forced to build their behemoths around her narrow dwelling, preserving it as part of the cityscape.

More than 130 years after the house and the four others in the row made their debut, it’s the only survivor.

[Second image: NYPL Digital Collections; fourth image: Brooklyn Eagle; sixth image: NYC Department of Records & Information Services]

June 2, 2025

What caused the 1904 General Slocum disaster, according to one bitter newspaper illustration

Which of New York City’s 15 daily newspapers ran this illustration referencing the General Slocum disaster isn’t clear. And exactly when it was published is unknown to me as well.

But it might have appeared after the completion of a federal investigation pinpointing the cause of the tragedy, which happened on the morning of June 15,1904 when a steamship taking parishioners from a German Lutheran church in the East Village to a Long Island picnic ground caught fire in the East River.

An estimated 1,021 people died in the disaster, mostly women and children from the city’s Little Germany neighborhood who belonged to the church on East 6th Street. Later that month, President Theodore Roosevelt commissioned the investigation.

The report, released in October 1904, pointed the finger mainly at the Slocum’s owners and crew.

“Although there were many revelations of corruption and graft tied to the administrators of the company, the inspectors who cleared the Slocum for service, and the manufacturers of the faulty lifejackets on board, only Captain William Van Schaick was found guilty of criminal negligence and manslaughter,” noted a 2016 post from The New York Historical.

The report contained many pages. But the newspaper that published the illustration distilled the cause of the disaster and the deaths of hundreds of kids to one overriding drive: greed.

[Illustration: via Village Preservation]

June 1, 2025

Discovering two of the hidden backhouses secluded inside an East Village tenement block

Like so many New York neighborhoods of densely packed tenement streets, the blocks that make up the East Village contain secrets.

Hidden from sidewalk view behind walls of brick and masonry are private gardens, residents-only patios, early burial grounds, and backhouses—a second house (or rear house, as they were known in the 19th century) built behind a street-facing dwelling.

Discovering these backhouses isn’t easy, as they typically aren’t visible from the sidewalk. Occasionally a horsewalk behind a gate tips you off, but backhouses built before the mid-19th century typically don’t have these narrow walkways designed to lead to a rear stable.

But sometimes you notice hints. On a recent walk down East 12th Street between First Avenue and Avenue A, I came across a tenement with an intercom marked “423 Rear”—in other words, the entrance to the rear house.

A slender passageway beside the front house at 423 East 12th Street took me to the backhouse. This tenement-style dwelling was separated from the front building by a patio with tables and chairs, a landscaped circle of greenery, and artwork that gave the space a very East Village vibe.

Next door stood a second tenement backhouse behind 425 East East 12th Street; the dwelling had ivy crawling up part of the facade and was blocked off by a stone wall.

What’s the backstory of these backhouses? First, let’s start with the front tenements they sit behind (above).

Both 423 and 425 East 12th Street were constructed around 1850 by a man named Hugh Cunningham, according to Village Preservation’s East Village Block Finder. The building of these houses coincided with the rapid development of today’s East Village from farmland to a hamlet called Bowery Village and into a full-fledged urban residential neighborhood.

The growth of the area was fueled by Irish and German immigrants, who moved into hastily built tenant houses and converted single-family row homes.

Shipbuilding and manufacturing along the East River needed workers, resulting in a population explosion from 18,000 in 1840 to 73,000 by 1860, according to East Village/Lower East Side Historic District Designation Report.

Nothing more is known about Hugh Cunningham. But at some point, he decided to build identical backhouses behind each of his front-facing tenements.

Why he did so is also a mystery, but the motive was almost certainly financial. Cramming two houses on a lot designed for one would have doubled his rent rolls.

The practice wasn’t legal, but that didn’t stop owners from putting up backhouses out of view of the street in the East Village, West Village, Gramercy, Chelsea, and other older Manhattan neighborhoods.

There were no shortage of people needing a place to live on the booming East Side. Those who lived in the front tenements at numbers 423 and 425 in the 19th century held working class jobs, according to newspaper archives, like factory worker, laborer, and varnisher. It can be assumed that the tenants in the backhouses took similar jobs.

The backhouse behind 423 East 12th Street gained lurid notoriety in 1892, when carpenter Philip Cunningham—perhaps related to Hugh, but it’s unclear—murdered his wife by stabbing her with a knife and striking her with a lamp during a drunken fight.

“On the second floor of a dreary tenement house in the rear of No. 423 East 12th Street lived Philip Cunningham and his wife, Elizabeth,” reported The World. The couple “spent the greater part of their time drinking and quarreling.”

Neighbors heard a commotion on the night of the murder but didn’t investigate. “‘The old man is beating the old woman again,’ said the tenants to each other,'” according to The World. Cunningham was found in a bar and arrested.

These days, the two backhouses don’t make it into the newspapers, and tenants seeking peace and privacy probably prefer it that way.

Not surprisingly, they aren’t the only backhouses inside the block. A Google map view (above) shows at least three more bounded by First Avenue, Avenue A, East 12th Street, and East 13th Street.

About the Google map view, what’s with the large yellow tenement close to First Avenue constructed at an angle? It’s not a backhouse, as it’s connected to 407 East 12th Street.

The building is angled that way to follow a road laid out in 1787, before the city street grid came into play. The angle followed Stuyvesant Street, “which formerly extended east from its present-day location and at a thirty-plus degree angle to the New York City grid,” states Village Preservation.

One East Village block; many long-held secrets.

May 26, 2025

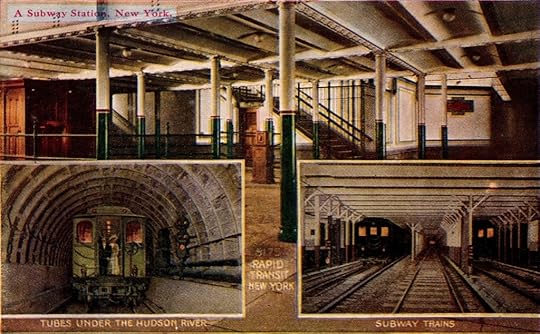

A vintage postcard reveals the difference between the subway and the Hudson Tubes

The Hudson Tubes—aka, today’s PATH trains to and from the New Jersey cities of Hoboken, Jersey City, and Newark—opened in 1909. That was only five years after the New York City Subway made its debut.

To herald these two underground mass transit options and perhaps shine light on the differences to a curious public, a postcard was created showing side-by-side images of the Hudson Tubes and a subway station.

What does this circa-1910s comparison tell us?

Well, the trains themselves look pretty similar. But while the subway station has hard angles, the Hudson Tubes are, well, actual tubes. And a well-dressed man and woman could stand at the edge of the last car as it shuttled through the tube and take in the wonder of this new rapid transit reality.

[Postcard: Ebay]

The three New York City memorials built to honor the prison ship martyrs of the Revolutionary War

Every war has its especially brutal aspects. During the Revolutionary War, few events were more brutal than the treatment aboard the prison ships anchored in the East River off Brooklyn.

These 12 to 16 ships, already in decrepit condition and moored in Wallabout Bay near the future site of the Brooklyn Navy Yard, were used by the British to house captive Patriots following the Battle of Brooklyn in 1776.

Throughout the war, thousands of prisoners were held, and their treatment at the hands of British soldiers is hard to fathom.

“In filthy, airless, overcrowded holds, they perished of disease and starvation; there are accounts of men so hungry they gnawed their own flesh,” wrote Elizabeth Giddens in a 2011 New York Times article. “They might have secured their release by joining the British forces, yet all but a few refused.”

An estimated 11,500 prisoners died on the ships (above, the most notorious ship, the Jersey), their bodies tossed overboard or hastily buried on the Brooklyn riverside.

After the war, the task of memorializing the men now recognized as the prison ship martyrs fell to Brooklyn—likely because their skulls and bones began gruesomely washing up on Brooklyn’s shores at low tide.

The first monument in their honor came about in the early 19th century.

In 1808, Brooklynites collected enough remains to fill 13 caskets, which were interred in a vault in today’s Vinegar Hill at Hudson Avenue between Front and York Streets, according to the New York Cemetery Project. The reburial ceremony was quite important to local residents; it was attended by 15,000 people.

This first simple memorial to the martyrs became even more meaningful in 1828 when a Tammany Hall politico who owned the land beneath the vault added decorations and inscriptions (above), per the New York Cemetery Project.

Within a few decades, as Brooklyn transitioned into a city and development boomed, the vault was mostly forgotten.

Enter the second memorial, also in Brooklyn and just a few miles away. In the 1840s, the decommissioned Fort Putnam began transforming into Washington Park, a public city green space in today’s Fort Greene. A new crypt to hold 22 boxes of remains of the martyrs was created in the park in 1873, states NYC Parks.

A decade later, with plans for the Washington Inaugural Centennial gripping the city and a newfound interest in the American struggle for independence took hold, a push for a grander monument in what was eventually renamed Fort Greene Park gained support.

“In 1905, the renowned architectural firm of McKim, Mead, and White was hired to design a new entrance to the crypt and a wide granite stairway leading to a plaza on top of the hill,” states NYC Parks. “From its center rose a freestanding Doric column crowned by a bronze lantern.”

This Prison Ships Martyrs Monument remains in Fort Greene Park today. It’s a moving place on high, shady ground surrounded by four bronze eagles mounted on granite posts.

The martyrs’ remains “lie buried in a crypt at the base of this monument,” reads a plaque added to the Doric column in 1960 by the Society of Old Brooklynites.

Apparently the monument has a staircase visitors could ascend to the top, but that’s long been closed to the public.

What about the third memorial honoring the prison ship martyrs? This one is across the river in Lower Manhattan in Trinity Church Cemetery.

You can see it from Broadway: in the northeast end of the cemetery is a Gothic-style, brownstone and granite structure (above). Towering over the faded and weathered headstones of the earliest New Yorkers, it almost looks like a felled church steeple.

Called the Soldiers’ Monument, it made its debut in the cemetery in 1852 to honor men held as prisoners at the Sugar House, a Lower Manhattan warehouse commandeered by the British into a prison for hundreds of POWs during the Revolution.

But the Soldiers’ Monument also memorializes another much larger group of prisoners, “the many soldiers who died while imprisoned on prison ships docked around the city throughout the Revolutionary War,” notes Trinity’s website.

May 25, 2025

An ironworks foundry leaves its unusual mark on a Grand Street manhole cover

Stars, circles, curlicues, bubbles of glass—the late 19th and early 20th century manhole covers marking the streets and sidewalks of New York City contain all sorts of embossed visual motifs.

And almost always, the name of the ironworks foundry that created the cover is incorporated into the design. (These raised designs exist not to delight pedestrians but to keep people and horses from skidding across roadways in wet weather.)

But the makers of this metal cover on the gritty northwest corner of Grand Street and the Bowery—in front of the circa-1902 Bowery Bank of New York building—chose a more understated presentation.

At first glance, there’s almost no design at all, just a series of short raised bars. Then in the center is a faded and weathered bronze knob with the name of the foundry in an early 1900s font.

“Franklin Iron Works,” it reads. “One Franklin Square, New York, NY.”

The always informative website run by Walter Grutchfield, chronicler of manhole covers and other remnants of New York’s past, states that Franklin Iron Works melded metal at One Franklin Square from 1919 to 1949.

Franklin Square? This bustling junction at Pearl, Dover, and Cherry Streets established in the early 19th century was home to Harper’s Weekly and a Third Avenue El station. The square was demolished and replaced by a Brooklyn Bridge approach in 1950—a year after the ironworks left its East River-adjacent home.

Franklin Iron Works hasn’t been based in New York City for 76 years, and its imprint on city streets seems to be limited. Grutchfield has a photo of an identical manhole cover from this foundry on Wooster Street, but I’m unaware of any others.

So what’s the point of calling out this relic? It’s an unusual and easily missed example of how small companies leave their mark on the city—not in the form of a building or park or restaurant but as a functional object underfoot.