Esther Crain's Blog, page 8

March 24, 2025

Two lovely subway station “head houses” from the early 1900s that are still part of the cityscape

The New York City subway recently celebrated its 120th birthday. With such an impressive life span, it’s realistic to expect that many features of the original stations have been altered, removed, destroyed, or otherwise lost to the ages.

But occasionally you come across a subway station that has been strangely left alone or only slightly renovated over the decades. Case in point is this head house for the Bowling Green 4 and 5 train station at Battery Park.

What’s a head house? Also called a control house, it’s the official term for a subway entrance that’s more of a structure than simply a kiosk with a staircase. Many early subway stations in New York had beautiful decorative kiosks, though sadly none survive today. (That one at Astor Place is a recreation).

New York City’s original head houses were designed to be ornate and decorative; the idea was that taking the subway should be an experience enhanced by artistic beauty wherever possible.

Built in 1905, the Bowling Green head house is the work of the architectural firm of Heins & LaFarge, states the Landmarks Preservation Commission. This storied firm was hired to design all of the IRT stations that opened in the early 1900s.

If you’ve ever seen interior images of the long-closed City Hall station, then you’ve seen the beauty that Heins & LaFarge created for New Yorkers.

A lovely little building of yellow brick, limestone, and granite, this head house with its gables and “bulls-eye” designs on each end remind me of the Flemish-style architecture of the city’s earliest colonial settlers. I imagine Heins & LaFarge designed it this way to pay homage to Gotham’s beginnings.

A few other head houses from the original IRT stations survive as well. One is the head house at West 72nd Street, which dates to 1904, according to another Landmarks Preservation Commission designation report.

The West 72nd Street head house (third photo) looks similar to Bowling Green; it’s described as “Flemish Renaissance style” and was also designed by Heins & LaFarge, per the report.

A third head house sits on Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn, or at least I remember one there last time I visited. Please don’t tell me it’s been demolished!

Her social power fading and New York changing, a look at the last years of Mrs. Astor’s life

In the prime of her life at the height of the Gilded Age, Caroline Schermerhorn Astor was New York City’s undisputed social doyenne.

The gatekeeper of high society (a role she appointed herself to after her mother-in-law’s death in 1872), “Lina,” as those close to her called her, presided over the social schedule in both New York and Newport, Rhode Island, helping define the extravagance of the 1870s and 1880s.

But in the following decade, the exclusivity and rigid traditions of society began to loosen and become more vulgar. Mrs. Astor, born in 1830, was also getting on in years.

“The active influence Mrs. Astor enjoyed over society peaked in 1891,” wrote John D. Gates, author of The Astor Family.

Times were changing, and Mrs. Astor’s role as the head of society was changing as well. In these last years of the Gilded Age, as the 19th century gave way to the 1900s, what was her life like?

She started the 1890s as a widow. In 1892, her husband (below photo), William Backhouse Astor, Jr., died of an aneurysm in Paris. William Astor never had any interest in his wife’s social events and preferred sailing his yacht as far from New York as possible.

Mrs. Astor “went into mourning, more in the interest of good form rather than sorrow or bereavement,” wrote Gates.

The next year, her 34-year-old daughter Helen Roosevelt died of an overdose of laudanum. After another period of mourning, she “found society much changed,” wrote Gates. She faced a new generation of society queens who didn’t “accept the credentials of Mrs. Astor’s older circle.”

In the 1890s, she also changed houses. Her longtime brownstone mansion at Fifth Avenue and 34th Street—gifted to Mrs. Astor and her husband in 1853 by the Astor family after their marriage—was the site of her regular season of teas, dinners, and an annual ball held every January.

This mansion, where Mrs. Astor raised her five children and sat under her own portrait in the drawing room as she greeted invitees to her fabled balls, was now overshadowed by the new Waldorf Hotel (second photo). The hotel was built to intentionally annoy her by her former next-door neighbor and nephew William Waldorf Astor.

So Mrs. Astor left Murray Hill and traded up to a French Renaissance palace (above photo) on Fifth Avenue and 65th Street, with a magnificent marble staircase and a ballroom big enough to hold 1,200 guests. She shared this double mansion, designed by Richard Morris Hunt and completed in 1896, with her only son, John Jacob Astor IV.

In Mrs. Astor’s half of the double mansion, she continued to host social events, like a formal dinner for Prince Louis of Battenberg with Victor Herbert’s orchestra as entertainment. (Below, an illustration of her annual ball in 1902.) But the end of her reign was near.

The ball held on January 8, 1905, were she received her 800 guests wearing purple velvet trimmed with sable and jewels that supposedly belonged to Marie Antoinette, would be her last.

Her health was fading. Now in her 70s, she remained in the “splendid isolation of her chateau on Fifth Avenue,” wrote Greg King in his book, A Season of Splendor: The Court of Mrs. Astor in Gilded Age New York.

She suffered a nervous breakdown, according to a 1908 New York Times article, and the following summer didn’t return to her Newport mansion, Beechwood.

Interrupting her isolation was an interview she gave in 1908 to a reporter from the Delineator, a women’s fashion and general interest magazine.

Mrs. Astor spoke about her role as a society leader as if she still had the role, and then hinted at her mortality. “I am not vain enough to believe that New York will not be able to get along without me,” she stated. “Many women will rise up to fill my place.”

Later that year, Mrs. Astor fell down her marble staircase. “Servants found her moaning on the floor, her halo of white hair caked in blood,” wrote King. A doctor stitched the cuts she sustained to her head. Though the wounds healed, her mind was never the same.

“The great chateau on Fifth Avenue fell into a gloomy silence, as rooms once filled with music and laughter were shuttered, their furniture hidden under dust covers and chandeliers swathed in netting,” continued King.

“In the mornings, Caroline received her butler, discussing details for dinners that would never take place, and discussed guest lists for imaginary balls. . . . In the evenings, after her customary carriage ride through Central Park, Caroline received her silent, empty house.”

As her dementia worsened, her mind retreated to the past; at one point she was convinced she was pregnant and began preparing a nursery.

She died on October 30, 1908 after being confined to her bed due to heart palpitations, according to King.

Her son (above portrait) and his wife had been by her bedside, but only daughter Carrie (at left) was with her in her final hour.

Rumors had swirled over the past few years that Mrs. Astor was in decline, so the news of her death wasn’t a surprise. Newspapers paid tribute to this fabled and feared New Yorker. Not only was it the passing of a formidable woman, but the passing of an era.

Her funeral was held in her Fifth Avenue mansion, and she was buried beside her husband in the Astor mausoleum (above photo) at Trinity Cemetery on West 153rd Street.

Erected in her memory by Carrie in 1914 is the Astor Cross. The cross stands tall in the cemetery at Trinity Church on Lower Broadway—the same church where Mrs. Astor was married and soon began her rise as a woman of so much influence, contemporary audiences continue to be fascinated by her.

[Top image: NYPL Digital Collections; second image: MCNY 93.1.1.17178; third, fourth, fifth, sixth, and eighth images: Wikipedia; seventh image: NYPL Digital Collections; ninth image: Find a Grave]

March 17, 2025

An elegy for an iconic, now-shuttered cigar store in Greenwich Village’s Sheridan Square

It opened in the early 20th century as Union Cigars in a triangular space between Seventh Avenue South and Christopher Street—the major crossroads of Greenwich Village.

As of last year, Village Cigars shut its doors due to a rent dispute, as Curbed reported in February 2024.

It’s not just any downtown shop that’s turned out the lights and closed up. Village Cigars is something of a symbol of Greenwich Village, and seeing it darkened and empty is a reminder that no space no matter how iconic is safe from disappearing forever.

While we wait to see if a reopening is in the future, take a look at this image of the storefront from 1940. It’s a very different Village, with men in the 1940s uniform of long coats, hats, and newspapers tucked under their arms.

But the subway-flanked storefront is instantly recognizable. Zoom in close to the front entrance, and you can even see the triangle-shaped mosaic embedded in the sidewalk that marks what was once the smallest plot of private land in New York City (Village Cigars bought it in the 1930s).

The storybook-style Gramercy carriage house built in 1893 by a “bachelor maiden”

As readers of this site know, I have a soft spot for carriage houses—those fanciful remnants of Gotham’s horse and carriage era tucked on side streets throughout the city.

I’ve chronicled many of these survivors over the years, peering into their backstories and discovering how they function in contemporary New York. So when I came upon this blond brick holdout on East 22nd Street, I fell in love, then decided to look into its story.

As it turns out, this carriage house has something unusual in its history. It’s not the fairy-tale vibe stemming from the porthole windows and terra cotta decoration, though these features make it all the more delightful.

Nor is it the stepped gables on the roof. Designed in the Flemish Renaissance style, the roof harkens back to Manhattan’s earliest days of Dutch colonization, when so many 17th century buildings had this characteristic architecture (and were sadly lost through demolition and fire).

What makes 150 East 22nd Street different from the city’s other lovely carriage houses is that rather than being built for a wealthy man, it was commissioned by a woman—prominent society scion Eloise L. Breese.

Breese, a descendant of an old money New York family (perhaps the inspiration for the carriage house’s Dutch-style design?) lived in a townhouse at 35 East 22nd Street in the Madison Square neighborhood.

Like other society women of the Gilded Age, her comings and goings were written up in newspapers. She held receptions with music, for example, and showed her Brittany spaniel at the Westminster dog show. She also entertained at her country cottage in the Gilded Age hotspot of Tuxedo, New York—where her banker brother owned a home as well.

But Breese was determinedly different from other society ladies. For one thing, she was unmarried for most of her life, with newspapers calling her a “bachelorette” or “bachelor maiden.”

She was also independent. “She was the only female member of the New York Yacht Club,” according to one website that chronicles her life. “Her steam yacht, the Elsa, had a swan shaped prow, like the boat in Lohengrin, because Eloise was also a devotee of the opera.” She reportedly had her own box at the Metropolitan Opera Houae.

Breese sailed her yacht in the late 1890s, the decade when she decided to have a carriage house built. To design it she turned to Sidney V. Stratton, an architect who studied in Paris but practiced his craft mostly in New York City. The carriage house was completed in 1893, per the AIA Guide to New York City.

Like so many carriage houses of the era, the design was meant to be a stylish statement, a totem to the wealth and interests of its owner. I’m not sure what Breese wanted it to convey, and I also imagine she spent very little time there. A groom and driver would have managed the horses, and when she needed transportation, the carriage would be driven to the front of her home a few blocks west so she could step inside.

Breese died in 1921, which was 15 years after her “surprise” Tuxedo wedding to widower Adam Norrie. Of the marriage, a New York Times writer stated that the former Miss Breese “has for some years refused all importunities to change her name and state.”

By the time of her death, horse-powered New York had been replaced by automobiles. A century later, Breese’s carriage house serves as a garage for the occupants of the five-story, glass-walled townhouse built behind it.

It’s unique and unusual even today. Unlike so many other carriage houses, it wasn’t remade into an art studio or cute private home!

[Third image: Find a Grave; fourth image: Wikipedia]

March 16, 2025

Meet the 19th century Riverside Drive visionary who was dubbed “the father of the Upper West Side”

Just inside Riverside Park at 83rd Street is a modest, low-key memorial: a bronze tablet affixed to a rock outcropping dominated by a bas relief of a man’s head.

It’s easy to miss this tablet, as many of the dog walkers and parents watching their kids scampering around the rocks seem to do. If you happen to notice it, the decorative wreath might prevent you from seeing the man’s name in small capital letters: Cyrus Clark.

Who was Cyrus Clark, and why was this inconspicuous marker placed here in his memory?

As the description on the tablet hints, this former silk merchant and early property owner on Riverside Drive led the development of the part of Manhattan known in the late 19th century as the West End, then the Upper West Side during the 20th century.

Clark’s efforts to guide the creation of the neighborhood were so appreciated, he was dubbed “the father of the West End” after his death in 1909. His work and devotion are still reflected in the area today, which is why he’s also referred to as the “father of the Upper West Side.”

To put Clark’s accomplishmentts in context, it helps to time travel back to the Upper West Side in the years following the Civil War.

In the 1860s and 1870s, Manhattan’s East Side was undergoing rapid development—spurred on by the opening of Central Park, a citywide population boom, and the northward extension of elevated train and streetcar lines.

Meanwhile, the area stretching from the west side of Central Park to the Hudson River largely remained a collection of small villages like Stryker’s Bay and Harsenville, reached by the . (Second photo, a farmhouse on West End Avenue; third photo, an old house on 86th Street and Riverside Drive)

In this mostly agrarian enclave, wealthy estate owners, farm families, and shack dwellers co-existed as spaced-apart neighbors. But the face of this bucolic section of New York City was about to change.

The popularity of Central Park marked the West End for urbanization. By the 1880s, rows of handsome houses began to rise, and then the first apartment buildings (photo below, the Dakota). The elevated railroad roared above Columbus Avenue, and streetcars plied Amsterdam Avenue.

Riverside Drive—a street grid–defying avenue that opened in 1880 and followed the irregular contours of the new Riverside Park—would soon transform into a “millionaire mile” to rival Fifth Avenue.

Amid these changes, enter Cyrus Clark. Born in 1830 in Erie County, New York, he came to Gotham in 1849 and made his fortune as a wholesale silk dealer. In the 1860s he purchased land on the West Side, retired to Europe, then spent the next three years learning everything he could about “real estate and civic administration,” stated the New-York Tribune.

Clark returned to New York in 1870. A family man who followed the customs of the Gilded Age by joining several elite clubs, he set out to be an advocate for the transformation of the section of Manhattan he invested in and eventually called home.

“He was a founding member of the executive committee, and was later the president of the West Side Association (WSA), formed by a group of influential businessmen in 1870 to promote public improvements north of 59th Street and west of Central Park,” states NYC Parks.

“In its early years, the WSA lobbied on behalf of public street and park improvements, and the extension of rapid transit to the area. They helped to bar commercial properties from West End Avenue, and promoted its exclusivity.”

Exclusivity isn’t a real-estate buzzword these days; development in contemporary New York tries (and often fails) to be inclusive. In the Gilded Age, however, West End property owners like Clark wanted to promote the area as a place of beautiful residences and stylish living—a cache the Upper East Side already had.

In the late 1880s, Clark built his own family home on some of the land he purchased two decades earlier (above photo). His was a three-story turreted limestone palace on the southeast corner of Riverside Drive and 90th Street. As a resident, he had even more reason to influence the area’s development.

By the 1890s, Clark had become president of an offshoot group, the West End Association, where he continued to advocate for the installation of street lights, street paving, and the separation of commercial and residential avenues. Ever notice that Broadway is the business artery of today’s Upper West Side, while West End Avenue and Riverside Drive are almost entirely residential? You can thank (or blame) Clark and his cohorts.

Some of the actions Clark lobbied for didn’t come to fruition for decades. One of these is the covering of the railroad tracks that ran along the Hudson River between the water’s edge and Riverside Park. Clark fought for the New York Central Railroad to bury the tracks underground, but that didn’t happen until the 1930s under parks administrator Robert Moses.

Other proposals never got off the ground. In 1890, Clark agreed with a city suggestion to relocate the Central Park Menagerie—housed on the East Side of Central Park at the Arsenal—to the northwest corner of the park. The menagerie was a popular park feature, and Clark’s thinking was that having it closer to the West Side would raise property values, according to an 1890 article in the New York Times.

By the time Clark died in 1909, he had moved from his Riverside Drive mansion to an elegant, bow-front townhouse on 76th Street between Riverside Drive and West End Avenue (above photo).

“After Clark’s death, friends, neighbors, and associates came together to commission a memorial in his honor,” wrote NYC Parks. It was completed and dedicated in 1911. (Below photo: Riverside Drive in 1909, the year Clark died)

The fact that the memorial went up just two years following Clark’s death reveals his popularity and influence in developing the West End. And the beauty and symmetry of much of today’s Upper West Side is a testament to the vision he had for the area more than 150 years ago.

Want to learn more about the fascinating backstory of Riverside Drive and the West End? Join Ephemeral New York on a Gilded Age Riverside Drive walking tour this Sunday, March 23, at 1 p.m. Sign up information and more details about the tour can be found here.

[Second, third, and fourth images: New York Historical; fifth image: Office for Metropolitan History via The New Republic; sixth image: New York Times 1895; seventh image: New York Historical; ninth image: LOC]

March 11, 2025

Ephemeral New York’s walking tours of Gilded Age Riverside Drive are back for spring!

I’m thrilled to let everyone know that Ephemeral New York’s Gilded Age Riverside Drive walking tours are back and officially on the schedule this spring—and ready for sign-ups!

More tours are planned through the year, but these are the first three of the season. Click the link for more information and how to get tickets.

• Sunday, March 23 from 1-3:30 PM done in conjunction with Bowery Boys Walks, part of the popular Bowery Boys long-running New York City history podcast.

• Sunday, April 6 from 1-3:30 PM in partnership with the New York Adventure Club, which offers hundreds of in-person and online events in and around New York City.

• Sunday, April 27 from 1-3:30 PM in conjunction with Bowery Boys Walks.

The tours start at 83rd Street and end at 107th Street. In between we’ll stroll up winding, lovely Riverside Drive and delve into the history of this beautiful avenue born in the Gilded Age, when the Drive became a second “mansion row” and rivaled Fifth Avenue as the city’s “millionaire colony.”

Each tour explores the mansions and monuments that survive, as well as the incredible houses lost to the wrecking ball. We’ll also take a look at at the wide variety of people who made Riverside Drive their home, from wealthy industrialists and rich business barons to noted actresses, artists, writers, and various characters and eccentrics.

Though the tour covers a lot of territory, we go at a breezy, conversational pace, with a few dips into Riverside Park. It’s a wonderful way to experience the history of New York City and learn about the little-known stories and secrets of this dramatic avenue high above the Hudson River. All are welcome!

[Top image: MCNY; second image: MCNY; third image: NYPL Digital Collection]

March 10, 2025

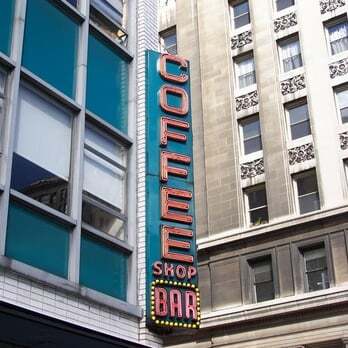

Missing the vintage neon coffee sign in Union Square that’s been transformed into a bank logo

It’s been seven years since the closure of Coffee Shop, a pioneering cafe on the west side of Union Square that since 1990 emanated coolness—especially with its vertical neon “Coffee Shop” sign.

A few years later, what moved into the space of this former model and celeb hangout? A Chase bank branch—which then put up its own vertical illuminated sign exactly where the Coffee Shop sign hung at the corner of the building at West 16th Street.

The strangely similar Chase sign, which added “Joe” at the end, a reference to Joe coffee next door, isn’t exactly new. But for those of us who don’t get to Union Square often, it’s always something of a surprise.

But here’s the weird twist: When Coffee Shop opened 25 years ago, it took over the space from a previous coffee shop called Chase, according to a 2018 eulogy by Robert Sietsema in Eater.

“Coffee Shop replaced an actual coffee shop called Chase but retained the coffee shop’s old neon sign that climbed the corner of the building, which said Coffee Shop in a gigantic font,” wrote Sietsema.

“In fact, it was probably one of the first places to ‘steal’ the identity of a previous establishment, imbuing the neon sign with a certain irony.”

From Chase to Coffee Shop and back to Chase again. Perhaps when the bank branch closes, another Coffee Shop can come in and continue the cycle?

[Top image: Alamy; third image: Yelp]

The last remaining street in the neighborhood once known as Italian Harlem

At its peak in the 1930s, Italian East Harlem was New York City’s biggest Little Italy—a tenement neighborhood stretching from about 96th Street to 125th Street between Lexington Avenue and the East River.

It’s been several decades since East Harlem was a predominantly Italian area. Following World War II, Italian Americans began moving to the outer boroughs or the suburbs, and Italian Harlem became known as Spanish Harlem, or El Barrio.

But there’s one remaining street that reflects a bit of the neighborhood’s Italian past. That would be Pleasant Avenue, which runs from 114th Street to 120th Street east of First Avenue.

It’s sort of an afterthought of a street. Once the northern end of Avenue A, Pleasant Avenue got a name change in 1879, according to NYC Parks. The new name reflected its then-rural character and was a “nod to its attractive waterfront setting,” wrote Michael Pollack in a 2004 New York Times column.

Those attractive waterfront days were on the wane. “The first Italians arrived in East Harlem in 1878, from Polla in the province of Salerno, and settled in the vicinity of 115th Street,” stated Gerald Meyer, Ph.D., formerly of Hostos College, City University of New York.

Rows of dumbbell tenements were hastily constructed, along with a handful of elegant walkup buildings. Commerce and industry, including stone works and coal yards, rose along the East River.

Through the early 1900s, an influx of Italians from other regions arrived. (Below, Pleasant Avenue looking west to 115th Street, 1930s)

“In Italian Harlem there was on East 112th Street, a settlement from Bari; on East 107th Street between First Avenue and the East River, people from Sarno near Naples; on East 100th Street between First and Second Avenues, Sicilians from Santiago; on East 100th Street, many northern Italians from Piscento; and on East 109th Street, a large settlement of Calabrians,” wrote Meyer.

Rather than being known for the Italian origins of its new residents, Pleasant Avenue earned its rep as a Mafia stronghold. The street’s first murder was reported in 1882, when a man was found on the street with his skull crushed. A New York Times article described the crime and called the street “a misnomer, for it is everything but pleasant.”

That murder never made it back into the news cycle and was apparently unsolved, so it’s impossible to tie it to organized crime. But by the mid-20th century, “Pleasant Avenue would become known as one of the most famous gangland stretches in the history of the mob,” wrote Manny Fernandez in the New York Times in 2010.

“It was where Anthony Salerno, known as Fat Tony, ran the Genovese crime family before he was convicted of racketeering in 1986,” stated Fernandez. “It was where Francis Ford Coppola filmed the scene in The Godfather when Sonny Corleone beats up his brother-in-law.” (Above, off 118th Street in the early 1970s)

Today, the organized crime influence has faded, if not disappeared completely—just like almost all the Italian American residents and businesses that made the area so rich and vibrant. But Pleasant Avenue keeps the neighborhood alive in small ways.

First, there’s Our Lady of Mount Carmel church (third photo), still an active Roman Catholic congregation and one of the first churches in Manhattan that served Italian immigrants. Completed in 1885, the church holds court on 115th Street just off Pleasant Avenue.

Then there’s the Giglio Feast. Held since 1908 (with a recent hiatus), this outdoor festival every August along Pleasant Avenue features the Dancing of the Giglio—a massive decorated tower carried through the Avenue by several men with very strong shoulders. It’s a tradition brought to many U.S. cities, but this is the only Giglio fest to my knowledge in Manhattan.

Finally, Pleasant Avenue also has one of Italian Harlem’s most famous and fabled restaurants, Rao’s (top photo). Originally a saloon owned by beer baron George Ehret, Rao’s became a restaurant when Charles Rao bought it in 1896.

Over the years this family-run space became a haunt for celebrities and the heads of various crime families, according to a 2015 New York Post article.

Rao’s southern Italian cuisine isn’t the main draw. Instead, it’s the restaurant’s regular crowd of power brokers, its unusual way of booking and reserving a table, and the sense of exclusivity that makes it the hardest place to get a dinner reservation in all of New York City.

[Second image: NYC Department of Records & Information Services; Fourth image: NYPL Digital Collections; fifth image: mubis.es]

March 3, 2025

A portrait of the stylish shop girls flowing en masse through turn of the century New York City

When Ashcan School painter William Glackens created this 1900 image of a group of shop girls moving with energy and vitality along a New York sidewalk, the concept of the working young woman was nothing new.

Shopgirls specifically emerged in the second half of the 19th century with the rise of consumerism, the garment industry, and the invention of the department store.

“Department stores hired more women and paid them less than their male counterparts,” states a post on Women & the American Story. “In 1880, fewer than 8,000 women worked as sales clerks. By 1890, that number had grown to over 58,000. By the early 20th century, female sales clerks outnumbered male clerks.”

Hard working and typically from the working or middle class, shop girls were featured in books, theater, popular songs, and early movies. The shop girl archetype captured the national imagination—and it seems it intrigued Glackens as well.

The shop girls here—maybe on Broadway or Sixth Avenue along Ladies Mile—are painted as a pack, chattering and lifting their stylish skirts as they traverse the sidewalk. There’s a sense of kinetic independence and happiness in this flowing feminine current.

Glackens chose to depict them in blues and grays, showing them as strong but not masculine. The tight composition enhances their strength and power. We don’t know what will become of them, but in this glimpse these shopgirls are owning the moment.

The push to get New Yorkers to conserve wheat by touting “war bread” and wheatless lunch menus

After the U.S. officially entered the Great War in 1917, a campaign fostered by the federal government urged Americans to support the war by reducing their consumption of certain foods—like meat, white flour, and sugar.

The goal was to save these ingredients for soldiers on the front lines as well as our European allies, who were at risk of famine.

Enter a new food entity known as “war bread.” Introduced to Gotham by a group called the New York Food Aid Committee, war bread was bread made with little or no white flour. In its place was rye, corn, or some other kind of less loved and less valuable grain.

The Food Aid Committee spread the gospel of war bread via automobile wagons they set up around the city, traveling to different neighborhoods and boroughs handing out recipes and demonstrating how to make this patriotic bread.

War bread even made it to restaurant menus, as this 1917 “wheatless” menu from Macy’s Lunch Counter in Herald Square reveals.

After the war ended in 1918, the campaign for war bread died out, though the rationing of wheat, sugar, meat, and other foods and products came back again during World War II.

Did Macy’s go back to a wheatless menu as well? I haven’t come across a surviving menu from that era, but the pressure for everyone to conserve what they could was strong.

[Top image: Alamy; second image: Reddit; third image: Library of Congress]