Esther Crain's Blog, page 3

August 11, 2025

Why the Greek goddess of sacred poetry and music stands tucked behind a fence on the Upper East Side

As anyone who has ever taken a walk through a city park knows, New York is rich with beautiful bronze statues.

Typically they grace a public space, often on a decorative pedestal or base and in a setting that underscores their importance (or their importance at the time the statue was completed).

Then there are the statues you come across in an unexpected place, say an ordinary city block. That was my curious introduction to this stunning sculpture of Polyhymnia, which sits behind a fence in a courtyard on East 87th Street steps from Fifth Avenue.

Poly who? Polyhymnia is the Ancient Greek goddess of lyric poetry. One of the nine muses, she’s a daughter of Zeus and also the goddess of music, song, and dance.

Here she stands on a marble base amid orange flowers and a wall of ivy; in front of her is a wrought-iron fence and gate. Clad in Classical garb and with a child beside her, she looks pensive, her eyes cast down toward the child. She appears to be holding a lyre.

So how did Polyhymnia end up on one of the most luxurious townhouse blocks in Manhattan? Her story begins in 1895 with the establishment of a group called Der Liederkranz Damen Verein.

The German name translates into “The Liederkranz Ladies’ Club.” This was an all-female auxiliary organization that supported the philanthropic and social activities of the Liederkranz Club—a singing society formed in New York City in 1847 for men of German descent.

In the decades before the Civil War, German immigrants came to New York by the thousands; in 1860, they comprised a quarter of the city’s population. Groups like the Liederkranz Club offered fellowship and culture for German newcomers as they navigated life in a not always welcoming metropolis.

“During the period preceding the Civil War, German American singing groups sprang up all over America, preserving German musical tradition and keeping the culture alive,” explained the website for the Liederkranz of the City of New York, the group’s current name. “Interest in the music of Germany was at its height.”

By the late 19th century, the group had hundreds of members. William Steinway, of Steinway Pianos fame, then became president of the Liederkranz. He helped guide members to raise funds for a clubhouse that was eventually built at 111-119 East 58th Street (below photo).

Two years after the Damen Verein formed, members commissioned sculptor Giuseppe Moretti to create the statue of Polyhymnia. It was presented as a gift for the clubhouse in 1897 to honor the Liederkranz Club’s 50th anniversary.

Facing a decline in membership after World War II, the Liederkranz sold the East 58th Street clubhouse. In 1949 members purchased the former Henry Phipps mansion—a 1904 granite and limestone Beaux Arts jewel built by this steel magnate turned philanthropist—at 6 East 87th Street.

When the Liederkranz moved to the Upper East Side, Polyhymnia came along, situated ever since in the small courtyard behind the wrought iron fence.

While the Liederkranz is still sponsoring music events and supporting cultural and social exchange, Damen Verein disbanded in 2009. Polyhymnia “serves as a permanent reminder of the spirit and generosity of the Damen Verein,” states the website.

And she’s a wonderful, slightly mysterious muse who will stop you in your tracks if you happen to find yourself on East 87th Street.

[Fifth photo: MCNY, X2010.11.5555]

Why the Greek goddess of poetry stands tucked away behind a fence on an Upper East Side block

As anyone who has ever taken a walk through a city park knows, New York is rich with beautiful bronze statues.

Typically they grace a public space, often on a decorative pedestal or base and in a setting that underscores their importance (or their importance at the time the statue was completed).

Then there are the statues you come across in an unexpected place, say an ordinary city block. That was my curious introduction to this stunning sculpture of Polyhymnia, which sits behind a fence in a courtyard on East 87th Street steps from Fifth Avenue.

Poly who? Polyhymnia is the Ancient Greek goddess of lyric poetry. One of the nine muses, she’s a daughter of Zeus and also the goddess of music, song, and dance.

Here she stands on a marble base amid orange flowers and a wall of ivy; in front of her is a wrought-iron fence and gate. Clad in Classical garb and with a child beside her, she looks pensive, her eyes cast down toward the child. She appears to be holding a lyre.

So how did Polyhymnia end up on one of the most luxurious townhouse blocks in Manhattan? Her story begins in 1895 with the establishment of a group called Der Liederkranz Damen Verein.

The German name translates into “The Liederkranz Ladies’ Club.” This was an all-female auxiliary organization that supported the philanthropic and social activities of the Liederkranz Club—a singing society formed in New York City in 1847 for men of German descent.

In the decades before the Civil War, German immigrants came to New York by the thousands; in 1860, they comprised a quarter of the city’s population. Groups like the Liederkranz Club offered fellowship and culture for German newcomers as they navigated life in a not always welcoming metropolis.

“During the period preceding the Civil War, German American singing groups sprang up all over America, preserving German musical tradition and keeping the culture alive,” explained the website for the Liederkranz of the City of New York, the group’s current name. “Interest in the music of Germany was at its height.”

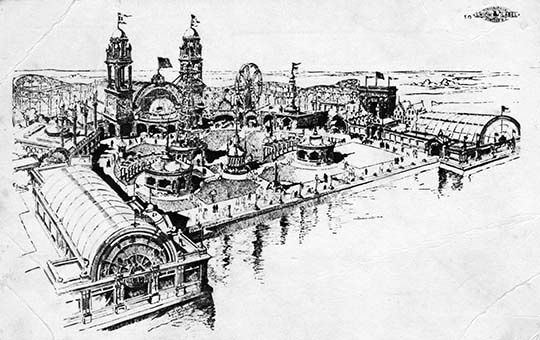

By the late 19th century, the group had hundreds of members. William Steinway, of Steinway Pianos fame, then became president of the Liederkranz. He helped guide members to raise funds for a clubhouse that was eventually built at 111-119 East 58th Street (below photo).

Two years after the Damen Verein formed, members commissioned sculptor Giuseppe Moretti to create the statue of Polyhymnia. It was presented as a gift for the clubhouse in 1897 to honor the Liederkranz Club’s 50th anniversary.

Facing a decline in membership after World War II, the Liederkranz sold the East 58th Street clubhouse. In 1949 members purchased the former Henry Phipps mansion—a 1904 granite and limestone Beaux Arts jewel built by this steel magnate turned philanthropist—at 6 East 87th Street.

When the Liederkranz moved to the Upper East Side, Polyhymnia came along, situated ever since in the small courtyard behind the wrought iron fence.

While the Liederkranz is still sponsoring music events and supporting cultural and social exchange, Damen Verein disbanded in 2009. Polyhymnia “serves as a permanent reminder of the spirit and generosity of the Damen Verein,” states the website.

And she’s a wonderful, slightly mysterious muse who will stop you in your tracks if you happen to find yourself on East 87th Street.

[Fifth photo: MCNY, X2010.11.5555]

August 10, 2025

This sweet 1820s house is a reminder that the Bowery was once a middle-class residential street

Before the raucous dance halls and concert saloons, before the earsplitting roar of the elevated train, before the bars, breadlines, beer gardens, flop houses, wholesale districts, and early 2000s transition into a luxury hotel district, the Bowery was a residential road of tidy, single-family houses.

For a short time, anyway. But first, a little backstory.

What was known as “Bowry Road” by the Dutch—who established New Amsterdam in the early 1600s—served as a carriage and wagon drive so the burghers who ran the colony could get to and from their farms on the outskirts of town. In the 18th century, cattle drovers herded their livestock on this former Native American footpath, close to the slaughterhouse district at the Collect Pond.

After the turn of the 19th century, New York was in the throes of a population boom, with about 60,000 citizens. The Bowery, as it was officially renamed in 1813, was eyed for residential development.

First the cattle pens had to go. Several wealthy neighbors who hoped to rid the Bowery “of its noise and filth” bought out slaughterhouse owner Henry Astor (older brother of John Jacob) in the 1820s, per the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

As the slaughterhouses began moving north to 23rd Street, vast family estates and small farms were sold off and carved up into new side streets. The gaslit, Roman temple-like Bowery Theater opened in 1826 and aimed to lure an elite clientele (fifth photo).

Thus began the Bowery’s stint as a fashionable address. Few of these early houses from the Bowery’s genteel era still stand. One that does is at 306 Bowery, across from First Street.

A mile or so north of where the Bowery begins at Chatham Square, this three-and-a-half story survivor is a relic of a street that by the 1830s “had become a bustling neighborhood composed in large part of brick and brick-fronted Federal-style row houses,” according to the Landmarks Preservation Commission.

Number 306 was built not by a family but as in investment. George Lorillard had the house constructed in 1820 “at a time when this area was developing with homes for the city’s expanding middle class,” states the Landmarks Preservation Commission’s 2003 report on the NoHo East Historic District.

Lorillard was the son of Pierre Lorillard, a French Huguenot who immigrated to New York around 1760 and started a snuff-grinding factory near Chatham Square.

By the 1820s, George Lorillard had taken over his father’s tobacco company and begun investing in real estate—building not just 306 Bowery but also 308 and 310 next door.

Number 306 had all the early 19th century touches that the family of a merchant or trader would desire: three stories, Flemish bond brickwork, sandstone lintels on and above the window sills, plus a half-floor with dormer windows and a peaked roof where a servant or two could board.

Who lived in this pretty little house? The earliest known tenant was a woman named Ann Fisher, who lived there in the 1820s, according to the LPC report. A notice announced that her funeral would be held in the house, or “her late residence,” as The Evening Post put it in 1838. She was 72 years old and the widow of Richard Fisher.

Lorillard sold the house in 1841. Maybe he sensed that the Bowery’s proximity to the Five Points slum district would eventually ruin the home’s value as an investment. Or he saw the Bowery’s low-rent future. Streetcars began running between Prince and 14th Street in 1832, states the Bowery Alliance, and the crowds at the Bowery Theater were increasingly coarse.

New residents moved in and out through the next several decades. A medical doctor, E.F. Maynard, lived there in the 1830s, per the 1837 Evening Post, and then bought it from Lorillard. Mahnor Day, a publisher and bookseller, was the next owner. After his death, his estate owned the house until 1899, according to the LPC report.

It was in the middle of the 19th century when the Bowery lost its appeal as a middle-class residential street. Commerce had moved in, then the rollicking vaudeville theaters, saloons, and late-night oyster houses. Working class and poor people, many who were German immigrants, rented rooms in the carved up old houses and new tenements.

Gang fights broke out. Criminals hung around, looking for easy marks. The Third Avenue Elevated began spewing steam overhead in 1878—two years after 306 Bowery underwent alterations to turn its ground floor into a storefront.

The era of the Bowery as an entertainment district was underway. 306 Bowery escaped major alteration (aside from a new fire escape, as seen in this 1940 photo) and remained a single-family home and ground-floor store until 1966, when it was portioned into artists’ studios.

Most recently the little house was home to a Patricia Field boutique, which closed in 2015. Its more heavily renovated sister houses at 308 and 310 Bowery are (or were) occupied by pricey drinking establishments.

The future feels uncertain for this 205-year-old remnant. But if you close your eyes and shut your ears, and you envision a front stoop instead of a storefront, you can almost imagine the house as it was in 1820 at the dawn of the Bowery’s brief turn as a respectable middle-class enclave.

[Third image: painting by William P. Chappel, Metmuseum.org; fifth image: NYPL Digital Collections; sixth image: NYC Department of Records & Information Services]

August 4, 2025

The mysterious blocked-off entryways built into a Central Park transverse road

There’s so much exquisite natural and structural beauty grabbing your attention in Central Park that you probably don’t give the transverse roads much thought.

You know the transverse roads. Part of Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux’s 1858 Greensward plan for the park, these four serpentine roads at 65th, 79th, 85th, and 97th Streets are sunk below the park’s grade and surrounded by stone embankments.

The transverse roads allow for east-west traffic through the park with as little disruption as possible. It’s a brilliant design element that helps park-goers feel removed from the usual urban distractions without stopping the flow of transit.

But the 85th Street transverse road presents a mystery: what was the purpose of these entryways on opposite sides of the road, and where did they lead?

With their Romanesque design, they seem to be original features built into the stone embankments, or perhaps late 19th century additions. The one in the first image is bricked in; the second is blocked by a locked gate.

Maybe they served as passageways for the men who built Central Park, so they could continue their work or maintain crucial park functions as the park opened in stages through the 1860s? Or perhaps they were storage areas that became obsolete in the 20th century and subsequently blocked off, no longer needed.

Whatever their original function, I get the feeling they add something interesting to Central Park’s backstory and how this jewel of a city park came to be—or how it continues to be such a wonderful respite for today’s New Yorkers.

What happened to the flashy amusement park nicknamed the Coney Island of Canarsie?

It was just a few miles on the Brooklyn shoreline from the real Coney Island—an amusement mecca of Greco-Roman towers, dance pavilions, and electric lights fronting a new boardwalk beside Jamaica Bay.

Opening to a crowd of 30,000 New Yorkers in May 1907 in the sparsely populated South Brooklyn area of Canarsie, Golden City, as its developers named it, satiated the fantasies of summertime fun seekers.

Built to rival the great amusement venues at Coney, Golden City’s nine acres of extreme rides and attractions dazzled the imagination.

There was the Coliseum Coaster, the “Over the Rockies” scenic railway, the Double Whirl (a ferris wheel with a revolving base), “Down the Niagara,” which sent riders on boats through rapids and whirlpools, and “Love’s Journey,” which had couples sitting side by side through dark tunnels while confetti was thrown at them.

Perhaps the most insanely creative ride was “Human Laundry,” where patrons “were washed in a giant tub, then spun dry, thoroughly dried by wind, pressed between upright rollers, and sent down a laundry chute slide to the street,” explains the website Lost Amusement Parks.

Like all great pleasure parks of the early 20th century, the wild rides were just the beginning. Dance halls, a bandstand, motorcycle daredevil shows, exotic animals, a funhouse, a carousel, vaudeville performers, and a skating rink rounded out the offerings.

“In addition to the rides, the park staged a number of live shows at ‘The Barbary Coast’ amusement hall, allowing Broadway stars to try out new material before bringing the act to the major stages in Manhattan,” states the Brooklyn Public Library.

The park’s most popular live action show, ‘The Robinson Crusoe Show,’ was a 22-minute telling of the Daniel Defoe novel that cost the park $60,000 to stage,” per the Library.

Sixty grand was a lot of money in 1907, and the entire park was estimated to cost at least half a million bucks to build and operate.

But Golden City’s developers bet that there was room for another amusement park in a city dominated by Coney Island, the Rockaways, and smaller pleasure palaces like the Fort George Amusement Park in Upper Manhattan and Starlight Park in the Bronx.

For several years, they were right. The completion of an elevated train to Canarsie and extension of surface lines in the early 1900s made it easier for day-trippers from all over Brooklyn to pay the nickel fare and get to Golden City faster than if they boarded a train for Coney.

“To many an ordinary man with a large family to take on an outing the saving in carfare will be a material consideration,” commented the Brooklyn Daily Times in May 1907.

Improved rapid transit and the influx of visitors made Canarsie, formerly a fishing hotspot, a resort-like area ready for big development. “Cool—Canarsie shore—Clean,” stated a 1916 ad featuring area hotels and restaurants. “The mecca for the pleasure seeker.”

By the late 1930s, however, Golden City sat empty, its visitors gone, concessions shuttered, and buildings condemned. What happened?

For starters, running an amusement park open only during warm-weather months is a challenge. The park was initially popular, and the developers announced that they were expanding it by 50 acres, according to Lost Amusement Parks. The price to get into the park rose to 25 cents—which perhaps wasn’t enough to break even.

Then there were fires. “In 1909, a fire that began in one of the park’s restaurants quickly spread, causing $200,000 worth of damage and destroying the restaurant, dance hall, photography gallery, and office,” states the Brooklyn Public Library. “The park was able to resume normal operations, but was the victim of fire again in 1912 when the Tunnel of Love was destroyed.”

The Great Depression put the final nails in the coffin. “The park was already losing money when a 1934 fire damaged the park so badly that management refused to rebuild,” explains the Brooklyn Public Library.

In 1938, New York City bought the Golden City site, with the understanding that the developers who owned it would hang onto it through September of that year. But Parks Commissioner Robert Moses “had his steam shovels scoop up and haul away the beer gardens, shooting galleries, and other amusements,” the developers alleged per a Brooklyn Citizen article in 1941.

Moses then remade the site into the Belt Parkway. Did any remnants from Golden City survive?

Just the carousel, apparently. Carved by the Brooklyn firm Artistic Carousel Company and installed at Golden City in 1912, it was salvaged by a Long Island amusement park called Nunley’s when Golden City closed.

After Nunley’s went out of business, the hand-carved painted horses were restored to their original beauty. What’s now known as Nunley’s carousel appears to be owned by the Long Island Children’s Museum—a Golden City relic of Brooklyn’s golden era as the cheap thrills capital of Gotham.

[Top image: Lost Amusement Parks; second image: Lost Amusement Parks; third image: Brooklyn Citizen; fourth image: ebay; fifth image: ebay; sixth image: Long Island Children’s Museum; seventh image: Center for Brooklyn History/Brooklyn Public Library]

July 28, 2025

The faceless men haunting the Third Avenue El in the twilight of the 1930s city

You can practically feel the clattering rush of the elevated train roaring above Third Avenue in this dramatic 1930s painting by Bernard Gussow, a Russia-born artist who was raised on the Lower East Side.

The amber train, twilight skies, and green and pink tints to the storefronts give rich pops of color to what could have been an ordinary scene of urban mass transit. The steel tracks cut through the cityscape with an energy that commands the center of the canvas and almost cleaves it in two.

Gussow seems to guide our eyes to the space illuminated under the tracks. And then things get creepy. What is it with the faceless men watching the woman in workday clothes, who appears to be startled by one man walking close behind her?

The painting is set at the end of the day, or perhaps early in the morning before it starts—two points in time when nighttime denizens occupy the same space as those who live their lives in the daytime.

It’s a narrative of contrasts: the concrete ground under the tracks and the heavenly blue skies above; the drab, expressionless men and the woman who communicates vulnerability; the convergence of day and night; the skyscrapers in the shadows while life on street level takes the spotlight.

Gussow captured many subway and elevated train scenes, often with a gentleness that has something to say about the anonymity of the modern city. But “Third Avenue El,” as this painting is plainly titled, feels darker and more mysterious.

The holdout houses on a former colonial-era farm by the East River meet the wrecking ball in 1914

It’s hard to imagine in today’s river-to-river concrete city, but Manhattan at one time was almost entirely an island of farms and estates.

As the colonial outpost once known as New Amsterdam transitioned into the city of New York, vast tracts of land were sold and parceled out to new owners and developers—who built urban neighborhoods to accommodate the booming population and surge in commerce and industry.

One by one, as the city expanded northward in the late 18th and 19th centuries, farms in today’s Greenwich Village, Murray Hill, Gramercy, Chelsea, and Midtown were sold off—disappearing into a cityscape of new homes, factories, mass transit hubs, and business spaces.

But farmland in the upper reaches of Manhattan held out for much longer, thanks to their relative remoteness. One of these was the farm of Peter Schermerhorn, which stretched from today’s 63rd and 67th Streets on York Avenue along the East River.

You know the old-money Schermerhorns. The patriarch of this Knickerbocker family arrived in New York from Holland in the 17th century and made his home in the Albany area. A century later, a branch of the family relocated to Gotham, becoming merchants, shippers (Schermerhorn Row on South Street is named for them), and landowners in Manhattan and Brooklyn (see Schermerhorn Street, which runs from Flatbush Avenue to Brooklyn Heights).

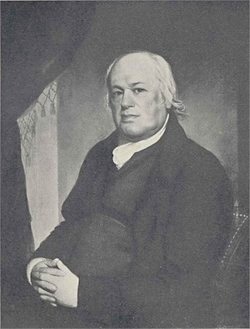

Peter Schermerhorn (right), a ship chandler and merchant, wasn’t the first settler to take hold of this expanse of riverfront. It was originally part of a larger estate owned by David Provoost, a descendent of a French Huguenot immigrant who made his fortune as a merchant.

The Provoost farm was divvied up in 1800, according to a 1922 New York Times story; Schermerhorn supposedly purchased it and added the farm to land he already owned to the north in 1818.

With the land came some outbuildings, including a pretty, colonial-style farmhouse (top two images) on high ground near the future East 63rd Street dating back to 1747.

“Early records state that the house was, for a time after the Revolution, the country home of General George Clinton, who became the first Governor of the State and afterward Vice President of the United States, and tradition also says that Washington visited Clinton at the house and enjoyed the peaceful river view from beneath one of the ancient trees,” reported the New York Times in another 1922 article.

Along with the farmhouse, the Schermerhorn farm had a pre-Revolutionary War chapel building and a cemetery for family members. Over the years, other buildings were added.

Surrounded by woodlands, the family’s nearest neighbors may have been the Jones family to the north, who owned an estate known as Jones Wood, which almost became the site of Central Park.

To the south was the and estate in today’s East 50s. In between would have been the still-standing Mount Vernon Hotel, built for President John Adams’ daughter as a home but by the early 19th century a summer resort for elite New Yorkers seeking cool breezes and countryside relief far from the sweltering city center.

What was life like in the 19th century on the Schermerhorn’s countryside farm estate, with its ornamental gardens and groves of trees? Probably isolated at first, but as the century went on, railroads and manufacturing invaded; streetcars and later elevated trains brought traffic and crowds to nearby avenues.

Both Peter and his wife Sarah passed away in the middle of the century. Their children inherited the property, and then their heirs. But according to a report by Rockefeller University, it appears that the Schermerhorn descendants moved to a new mansion on 23rd Street in the 1860s and no longer occupied the farmhouse.

A German immigrant, August Braun, leased half of the property and ran a successful boating and bathing facility at the river’s edge. In 1877, the Pastime Athletic Club built a running track on the other half of the estate, using the rundown chapel as a gymnasium.

By the turn of the 20th century, the urban city ringed the former farm, with tenements, apartment houses, and breweries constructed near what was still known as Avenue A; it wouldn’t be renamed York Avenue until 1928.

In 1903, a different kind of wealthy New Yorker took came calling: John D. Rockefeller, Jr. This financier and philanthropist son of the Gilded Age founder of Standard Oil had plans to build the Rockefeller Institute of Medical Research here, and he set about acquiring land for his new biomedical research facility.

Schermerhorn descendant William Schermerhorn (or his estate) sold the farm to Rockefeller. In the Institute’s early days, the roughly 150-year-old colonial farmhouse was repurposed as a nurses’ station and dispensary as part of a hospital for sick babies on the institute’s campus.

The hospital closed, and the farmhouse met the bulldozer in 1914—as did the chapel and the remnants of other outbuildings on the property that year or sometime before or after. (The cemetery remained sans the headstones, which were toppled and broken long before Rockefeller bought the land.)

Newspapers chronicled the passing of what was deemed the second-oldest house in Manhattan, but not all took a nostalgic ot wistful tone.

“When built in 1747 it was surrounded by woods on all sides but the river,” noted the Sun in 1914, which added that now the marked-for-destruction farmhouse was surrounded by brick medical institute buildings, “in which many wonderful medical wonders are being performed.”

In 1955, the institute became The Rockefeller University, maintaining its presence with a gated driveway and many buildings on sloped grounds overlooking the East River.

[h/t to the Urban Archive for featuring the Schermerhorn farmhouse in its latest newsletter]

[Top photo: Frank Cousins Collection/NYC Design; second photo: Frank Cousins Collection/NYC Design; third photo: Find a Grave; fourth image: The Rockefeller University; fifth image: The Rockefeller University; sixth image: NYPL Digital Collections; seventh image: The Rockefeller University; ninth photo: Frank Cousins Collection/NYC Design]

July 21, 2025

The strict rules of decorum at Rockaway Beach, established by a police captain in 1904

Wondering why the beachgoers in this Rockaway Beach postcard don’t look like they’re having much fun—with their heavy hats, head-to-toe bathing outfits, and stiff posture as they sit in wood chairs or stand near the water?

It might have something to do with some new beach rules instituted a few years earlier.

According to a 2017 article in the longtime Rockaway news site The Wave, an NYPD Captain named Louis Kreuscher was concerned that a surge in visitors to this popular summer destination in the early years of the 20th century might have a negative effect on morals and manners.

So he composed a list of etiquette violations, which The Wave published in an August 1904 edition. The rules included the following:

“No person or persons shall be allowed to sit on the sand under the boardwalk after dark; As the beach is a public place, kissing is strictly forbidden; No hand-holding allowed; Hugging is strictly forbidden and the beach is for the use of bathers and is not to be used as a trysting place…”

A Wikipedia page on the history of Rockaway Beach also referenced Kreuscher’s rules, adding that they allowed for the “censoring the bathing suits to be worn, where photographs could be taken, and specifying that women in bathing suits were not allowed to leave the beachfront.”

Not using the beach as a “trysting place” seems reasonable. But no hugging, handholding, or heading to the boardwalk in a bathing suit? At some point in the 20th century, these rules were ignored, then hopefully officially wiped off the books!

[Image: Hippostcard.com]

A movie mogul builds an opulent theater on Avenue B where his childhood tenement once stood

Marcus Loew grew up in the kind of deep poverty that serves as the flip side to the ostentatious wealth of New York’s Gilded Age.

Born in 1870 in what’s been described as both a tenement and a “wooden shack” on Avenue B and Fifth Street, his Austrian and German family struggled to make a living in a crowded part of the city known as Kleindeutschland, or Little Germany.

Loew left school early to hawk newspapers, work for a map maker, and sell men’s clothes. He then labored in a fur factory, according to Michael Benson and Craig Singer’s 2024 book Moguls: The Lives and Times of Film Pioneers. But his life and fortune were about to change.

At the turn of the century, with savings from his low-level jobs, this visionary opened penny arcades at Union Square and on 23rd Street. He soon built theaters that showed a mix of motion pictures and live vaudeville acts.

The rest, of course, is film history. Throughout the early decades of the 20th century, Loew operated a chain of luxurious, fantastical cinema palaces from Delancey Street to Times Square to Harlem, all designed to satisfy New York City’s obsession with this new form of mass entertainment.

Loew’s name still graces movie theaters today, though most of his early palaces have, sadly, long been demolished. That includes one curious theater that’s all but forgotten: the Loew’s Avenue B Theater, which opened at Fifth Street in 1913 (top photo, from 1917).

Like many of his theaters, Loew’s Avenue B was designed by Thomas Lamb. It was a decadent departure from the cheaply built tenements that otherwise lined the lower end of an unspectacular avenue.

“Loew’s Avenue B’s facade was clad in white terra cotta and featured over-sized arches and large windows,” states a 2013 post from Village Preservation. “It was a gleaming contrast to the brick tenements that surrounded it and an impressive design that was meant to evoke an exotic palace.”

Lion heads decorated the theater; films were accompanied by the sounds of a live organist. “For the residents of the neighborhood, the building and the entertainment it provided must have been a welcome bit of frivolity,” continues the post.

Avenue B and Fifth Street, on the margins of the Lower East Side of the early 20th century, doesn’t seem like the kind of street where a theater that fit almost two thousand people would thrive. And by the 1920s, with competition from other nearby theaters, it did begin to struggle to survive.

But Loew may have had a more personal reason for building his theater here: It’s exactly on the site of the tenement where he was born and raised in dire conditions.

Apparently the tenement was still standing, and Loew had his birthplace “demolished to make way for the luxurious 1,750-seat theater,” according to Cinema Treasures.

A 2020 post from Village Preservation by Sarah McCully contains this quote from Loew addressing the Avenue B theater on its opening night: “This is the most pretentious of the houses on our string, because my better judgment was over-balanced by my sentimentalism and my longing to do something better here than I ever did before.”

Loew died in 1927, just as his Avenue B palace began losing its audience. “Unable to compete with multi-screen movie theaters with the space and variety to accommodate later-20th century tastes, the Loews Avenue B Theater declined in use for the next several decades before finally closing in 1958,” states McCully.

“The theater stood vacant for a decade, in an increasing state of disrepair and despair, before it was finally demolished in 1968,” she continues.

The former site of Loew’s tenement birthplace, and then a magical movie palace, is now occupied by a luxury building.

[Top photo: New York Historical; third photo: Village Preservation; fourth image: NYC Department of Records & Information Services; fifth image: Village Preservation/Carole Teller’s Changing New York; fifth photo: Cinema Treasures/David Gahr]

July 20, 2025

The circular beauty of a “ferris wheel” sewer cover in the South Bronx

It was spotted on a walk through the Melrose section of the Bronx: an unusual manhole cover installed partly on a residential sidewalk but mostly on the asphalt of a parking lot.

Like most sewer and manhole covers, it’s a circle. Within that circle are eight smaller rings arranged around an inner circle, each with a vent hole, forming 36 half moon–like sections. It’s kind of an anti-Venn diagram, since none of the circles overlap.

In a city with many attractive utility covers, this one seems to have a special visual appeal. And there’s an added mystery: the embossed letters in the center circle that read “Sewer DSI.”

Sewer DSI? A little research reveals that DSI was shorthand for the Department of Street Improvements. This city agency formed in 1890 and covered two wards in the “annexed district“—aka the Southwestern Bronx, which until 1874 was part of Westchester County.

Street improvements—and streets in general—were in high demand in this section of the Bronx at the time. By the close of the 19th century, the Bronx was marked for change from semi-rural and remote to a modern part of the cityscape.

“The needs of this great and growing, but still partly undeveloped territory, are numerous and pressing, and include the opening of new streets, grading…new sidewalks, sewers, gas, and water connections,” explained a New York Sun article on the DSI.

Tasked with creating sidewalks and sewers, the DSI needed to install sewer covers. Why they picked this “ferris wheel” design is unknown, though I’m guessing that it was aesthetically pleasing and differed from the many other manhole covers, sewer grates, and coal holes of the era.

The ferris wheel term comes from Don Burmeister, who runs an eponymous website with a section exploring the backstory of different utility covers in New York City. “This design, which is somewhat suggestive to me of a ferris wheel, was the basis of sewer covers in the Bronx for at least 50 years,” wrote Burmeister, who found multiple examples of this design in the Bronx, Northern Manhattan, and even Brooklyn.

Seeing similarities between this sewer cover and a ferris wheel seems especially fitting, considering that these DSI covers appeared in the 1890s—the same decade that saw the debut of the first Ferris Wheel, seen above when it opened at Chicago’s World Columbian Exposition in 1893.

[Second image: Wikipedia]