What happened to the flashy amusement park nicknamed the Coney Island of Canarsie?

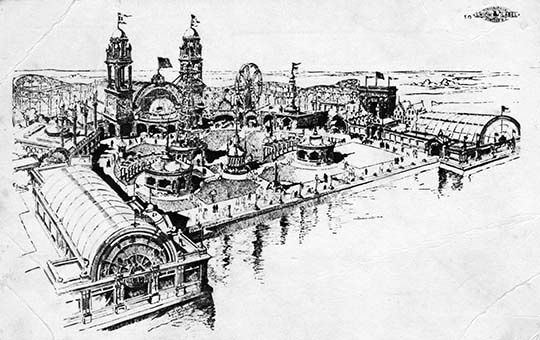

It was just a few miles on the Brooklyn shoreline from the real Coney Island—an amusement mecca of Greco-Roman towers, dance pavilions, and electric lights fronting a new boardwalk beside Jamaica Bay.

Opening to a crowd of 30,000 New Yorkers in May 1907 in the sparsely populated South Brooklyn area of Canarsie, Golden City, as its developers named it, satiated the fantasies of summertime fun seekers.

Built to rival the great amusement venues at Coney, Golden City’s nine acres of extreme rides and attractions dazzled the imagination.

There was the Coliseum Coaster, the “Over the Rockies” scenic railway, the Double Whirl (a ferris wheel with a revolving base), “Down the Niagara,” which sent riders on boats through rapids and whirlpools, and “Love’s Journey,” which had couples sitting side by side through dark tunnels while confetti was thrown at them.

Perhaps the most insanely creative ride was “Human Laundry,” where patrons “were washed in a giant tub, then spun dry, thoroughly dried by wind, pressed between upright rollers, and sent down a laundry chute slide to the street,” explains the website Lost Amusement Parks.

Like all great pleasure parks of the early 20th century, the wild rides were just the beginning. Dance halls, a bandstand, motorcycle daredevil shows, exotic animals, a funhouse, a carousel, vaudeville performers, and a skating rink rounded out the offerings.

“In addition to the rides, the park staged a number of live shows at ‘The Barbary Coast’ amusement hall, allowing Broadway stars to try out new material before bringing the act to the major stages in Manhattan,” states the Brooklyn Public Library.

The park’s most popular live action show, ‘The Robinson Crusoe Show,’ was a 22-minute telling of the Daniel Defoe novel that cost the park $60,000 to stage,” per the Library.

Sixty grand was a lot of money in 1907, and the entire park was estimated to cost at least half a million bucks to build and operate.

But Golden City’s developers bet that there was room for another amusement park in a city dominated by Coney Island, the Rockaways, and smaller pleasure palaces like the Fort George Amusement Park in Upper Manhattan and Starlight Park in the Bronx.

For several years, they were right. The completion of an elevated train to Canarsie and extension of surface lines in the early 1900s made it easier for day-trippers from all over Brooklyn to pay the nickel fare and get to Golden City faster than if they boarded a train for Coney.

“To many an ordinary man with a large family to take on an outing the saving in carfare will be a material consideration,” commented the Brooklyn Daily Times in May 1907.

Improved rapid transit and the influx of visitors made Canarsie, formerly a fishing hotspot, a resort-like area ready for big development. “Cool—Canarsie shore—Clean,” stated a 1916 ad featuring area hotels and restaurants. “The mecca for the pleasure seeker.”

By the late 1930s, however, Golden City sat empty, its visitors gone, concessions shuttered, and buildings condemned. What happened?

For starters, running an amusement park open only during warm-weather months is a challenge. The park was initially popular, and the developers announced that they were expanding it by 50 acres, according to Lost Amusement Parks. The price to get into the park rose to 25 cents—which perhaps wasn’t enough to break even.

Then there were fires. “In 1909, a fire that began in one of the park’s restaurants quickly spread, causing $200,000 worth of damage and destroying the restaurant, dance hall, photography gallery, and office,” states the Brooklyn Public Library. “The park was able to resume normal operations, but was the victim of fire again in 1912 when the Tunnel of Love was destroyed.”

The Great Depression put the final nails in the coffin. “The park was already losing money when a 1934 fire damaged the park so badly that management refused to rebuild,” explains the Brooklyn Public Library.

In 1938, New York City bought the Golden City site, with the understanding that the developers who owned it would hang onto it through September of that year. But Parks Commissioner Robert Moses “had his steam shovels scoop up and haul away the beer gardens, shooting galleries, and other amusements,” the developers alleged per a Brooklyn Citizen article in 1941.

Moses then remade the site into the Belt Parkway. Did any remnants from Golden City survive?

Just the carousel, apparently. Carved by the Brooklyn firm Artistic Carousel Company and installed at Golden City in 1912, it was salvaged by a Long Island amusement park called Nunley’s when Golden City closed.

After Nunley’s went out of business, the hand-carved painted horses were restored to their original beauty. What’s now known as Nunley’s carousel appears to be owned by the Long Island Children’s Museum—a Golden City relic of Brooklyn’s golden era as the cheap thrills capital of Gotham.

[Top image: Lost Amusement Parks; second image: Lost Amusement Parks; third image: Brooklyn Citizen; fourth image: ebay; fifth image: ebay; sixth image: Long Island Children’s Museum; seventh image: Center for Brooklyn History/Brooklyn Public Library]