Esther Crain's Blog, page 9

March 3, 2025

A passenger plane crashes on Rikers Island in the 1950s, and dozens of inmates assist survivors

Imagine if a plane took off from LaGuardia Airport on a stormy night and crashed in a snow-covered stretch of Rikers Island. Considering this island jail complex’s reputation for violence and chaos, it’s doubtful that inmates would be allowed to aid survivors.

But that’s exactly what happened when a passenger jet carrying 101 people departed LaGuardia in February 1957. It’s an incredible story of tragedy and heroism that’s hard to imagine in the New York City of today.

Before the details of the crash, here’s a primer on the backstory of Rikers Island. For its first century and a half after Dutch colonization, this spit of land in the East River was owned by the Rycken family, who lived on a farm in modern-day Astoria.

What did the Rikers, as they eventually renamed themselves, do with this 87-acre island? Aside from farming the land early on, not much. (Above, the East River from Rikers Island, date unknown)

During the 19th century, sleigh riding parties from Flushing crossed the ice on the frozen river to the island, and ships coming in from New England dropped anchor there. With the Civil War raging in the early 1860s, Rikers was used as a training ground for Union soldiers.

In 1884, the city bought Rikers for $180,000. The plan was to build a new jail that would relieve crowding in the penitentiary on nearby Blackwell’s Island. The Commission of Charities and Corrections, tasked with handling jails and public asylums, also wanted to separate “the institutions of the distressed and those for punishment of the guilty,” stated a 1886 New York Times article.

That new jail wasn’t completed until the early 1930s (above), following years of city officials using Rikers Island as a dumping ground of ash and street sweepings that eventually enlarged it to more than 400 acres.

Finally, “construction of 26 buildings consisting of seven cellblocks for 2,600 inmates, an administration building, receiving center, mess hall, shops, a chapel and homes for the warden and deputy warden” were opened to men only, according to the NYC Department of Records & Information Services.

Construction issues and scandal plagued the jail complex almost as soon as it opened. By 1954, Rikers was home to 7,900 inmates in space designed for 4,200, per the NYC Department of Records & Information Services.

Then came the crash. Northeast Airlines Flight 823 took off from LaGuardia Airport on February 1, 1957 in the middle of a storm on a freezing night.

The DC-6A with 95 passengers and six crew members failed to climb, and “the Miami-bound plane crashed into a patch of trees on Rikers Island, ripping off its wings and bursting into flames less than a minute after take-off,” wrote the New York Post in 2017.

A deputy warden made the decision to send 69 inmates, who were already on snow-removal duty, to the crash site to help pull survivors from the burned and broken aircraft.

“The first inmate to arrive at the scene worked as a housekeeper for the jail’s Protestant minister,” reported the New York Post. “He helped pull desperate passengers through the fuselage and doused their smoldering clothes with wet snow.”

The Staten Island Advance covered the story the day after the disaster, stating that 60 inmates were working in a poultry house that evening. They realized a plane had crashed when they saw an orange glow through the snow.

“You tell about the inmates,” the Advance quoted a police officer on the scene. “What they did! Without them, many would have died out there. They went right in there…they took [passengers] out in their arms.”

Besides pulling out the survivors, the incarcerated men brought them to the jail infirmary (above photo) and assisted in providing first aid. As emergency crews arrived on the island, rumors circulated that inmates were trying to escape. But per the Post, everyone was accounted for.

In total, 20 passengers were killed in the crash and subsequent fire. An investigation deemed the tragedy to be the result of pilot error.

As for the heroic inmates, nearly 60 “eventually had their sentences reduced or commuted because of their heroic efforts, wrote the Post.

Most of these former inmates remain unknown, as their names were not released publicly. In an era of daily newspapers and a handful of TV networks, not every individual who acted heroically made it into the media cycle. Presumably, most went on with their lives in anonymity.

[Top image: Life photo archive; second image: NYPL Digital Collections; third image: New York Corrections History; fourth image: NYC Department of Records & Information Services; fifth image: NYC Department of Records & Information Services; sixth image: Life photo archive; seventh image: Bureau of Airplane Accidents Archives]

A passenger jet crashes on Rikers Island in the 1950s, and dozens of inmates assist survivors

Imagine if a plane took off from LaGuardia Airport on a stormy night and crashed in a snow-covered stretch of Rikers Island. Considering this island jail complex’s reputation for violence and chaos, it’s doubtful that inmates would be allowed to aid survivors.

But that’s exactly what happened when a passenger jet carrying 101 people departed LaGuardia in February 1957. It’s an incredible story of tragedy and heroism that’s hard to imagine in the New York City of today.

Before the details of the crash, here’s a primer on the backstory of Rikers Island. For its first century and a half after Dutch colonization, this spit of land in the East River was owned by the Rycken family, who lived on a farm in modern-day Astoria.

What did the Rikers, as they eventually renamed themselves, do with this 87-acre island? Aside from farming the land early on, not much. (Above, the East River from Rikers Island, date unknown)

During the 19th century, sleigh riding parties from Flushing crossed the ice on the frozen river to the island, and ships coming in from New England dropped anchor there. With the Civil War raging in the early 1860s, Rikers was used as a training ground for Union soldiers.

In 1884, the city bought Rikers for $180,000. The plan was to build a new jail that would relieve crowding in the penitentiary on nearby Blackwell’s Island. The Commission of Charities and Corrections, tasked with handling jails and public asylums, also wanted to separate “the institutions of the distressed and those for punishment of the guilty,” stated a 1886 New York Times article.

That new jail wasn’t completed until the early 1930s (above), following years of city officials using Rikers Island as a dumping ground of ash and street sweepings that eventually enlarged it to more than 400 acres.

Finally, “construction of 26 buildings consisting of seven cellblocks for 2,600 inmates, an administration building, receiving center, mess hall, shops, a chapel and homes for the warden and deputy warden” were opened to men only, according to the NYC Department of Records & Information Services.

Construction issues and scandal plagued the jail complex almost as soon as it opened. By 1954, Rikers was home to 7,900 inmates in space designed for 4,200, per the NYC Department of Records & Information Services.

Then came the crash. Northeast Airlines Flight 823 took off from LaGuardia Airport on February 1, 1957 in the middle of a storm on a freezing night.

The DC-6A with 95 passengers and six crew members failed to climb, and “the Miami-bound plane crashed into a patch of trees on Rikers Island, ripping off its wings and bursting into flames less than a minute after take-off,” wrote the New York Post in 2017.

A deputy warden made the decision to send 69 inmates, who were already on snow-removal duty, to the crash site to help pull survivors from the burned and broken aircraft.

“The first inmate to arrive at the scene worked as a housekeeper for the jail’s Protestant minister,” reported the New York Post. “He helped pull desperate passengers through the fuselage and doused their smoldering clothes with wet snow.”

The Staten Island Advance covered the story the day after the disaster, stating that 60 inmates were working in a poultry house that evening. They realized a plane had crashed when they saw an orange glow through the snow.

“You tell about the inmates,” the Advance quoted a police officer on the scene. “What they did! Without them, many would have died out there. They went right in there…they took [passengers] out in their arms.”

Besides pulling out the survivors, the incarcerated men brought them to the jail infirmary (above photo) and assisted in providing first aid. As emergency crews arrived on the island, rumors circulated that inmates were trying to escape. But per the Post, everyone was accounted for.

In total, 20 passengers were killed in the crash and subsequent fire. An investigation deemed the tragedy to be the result of pilot error.

As for the heroic inmates, nearly 60 “eventually had their sentences reduced or commuted because of their heroic efforts, wrote the Post.

Most of these former inmates remain unknown, as their names were not released publicly. In an era of daily newspapers and a handful of TV networks, not every individual who acted heroically made it into the media cycle. Presumably, most went on with their lives in anonymity.

[Top image: Life photo archive; second image: NYPL Digital Collections; third image: New York Corrections History; fourth image: NYC Department of Records & Information Services; fifth image: NYC Department of Records & Information Services; sixth image: Life photo archive; seventh image: Bureau of Airplane Accidents Archives]

February 24, 2025

This two-block stretch of Lexington Avenue might be the steepest hill in Manhattan—and it has a forgotten name

Lenox Hill, Murray Hill, Carnegie Hill, Golden Hill—Manhattan used to have a lot of hills, and the island’s once-bumpy topography lent itself to neighborhood names still in use today. (Well, not Golden Hill, but I’m partial to bringing it back.)

But one true hill that remains on the streetscape spans Lexington Avenue between 102nd and 103rd Streets. To my knowledge, nothing like this steep slope exists below Washington Heights and Inwood—which are home to some pretty sharp inclines.

A hill like this is a strange thing to encounter in the flattened-and-smoothed-over Manhattan below 168th Street. I’ve walked it many times over the years and finally decided to look into its backstory.

First, this hill has a name. Duffy’s Hill, as it’s been known since before the Sun featured it in a story in 1886, was named for Michael J. Duffy, a Gilded Age builder who constructed more than 800 houses, “with the greatest concentration located between 94th Street and 104th Street between Third Avenue and Lexington Avenue,” states Ghosts of Gotham in a 2023 post.

Before Duffy developed the area, this was a neighborhood with its share of shanties and free-roaming goats—too far north to appeal to the millionaires building Upper East Side mansions.

“His impact on this part of East Harlem was so significant that people started calling the area Duffyville and he became known as the Mayor of Duffyville.”

Duffy was born in the East Village and sounds like the kind of minor politician who ingratiated himself to various Tammany Hall bigwigs. He ended up serving as an alderman for Duffyville in the 1880s, and he died in 1903 at age 67 in his home on East 103rd Street.

Before and after Duffy’s death, Duffy’s Hill was something like the East Harlem version of Death Avenue. Cable cars traveled up and down the hill, forcing them to suddenly accelerate and then slam on the brakes, which resulted in many casualties.

A guard was eventually stationed at 103rd Street to stop traffic when the cars needed to go up and down, per a 1933 New Yorker article. But that wouldn’t have stopped the mischievous boys who in 1921 sent an unoccupied limo hurtling down Duffy’s Hill, killing a girl on the street.

The Duffy’s Hill name made it into this 1911 Buick ad as one of New York’s most notorious hills. Per the New Yorker article, it’s actually the city’s steepest hill “on which surface cars are operated,” with a 14 percent grade.

One question remains: why didn’t Duffy or some other city official have it leveled? Ghosts of Gotham mentions the ridge of Manhattan schist that rises in uptown neighborhoods, so perhaps it was just geologically impossible to flatten at the time.

[Third image: The Sun]

The colonial-era burial ground underneath an MTA bus depot in East Harlem

With a tangle of open lots, tricky intersections, and bridge approaches, the area surrounding Second Avenue and 126th Street doesn’t bring colonial-era New York City to mind.

But under a sliver of land on the southeast corner of a decommissioned MTA bus depot (above) is a remnant of Gotham’s days under Dutch control: a burial ground intended for free and enslaved Africans active from 1653 until the mid-1800s.

Cemeteries for early black New Yorkers have been rediscovered in the past. The 1991 excavation for a new federal office building on Lower Broadway uncovered a colonial-era burial ground of thousands of Black residents that’s now a national monument. A slave burial ground in Hunts Point recently received landmark status.

The story of this burial ground, in the then-undeveloped farm village of Harlem, begins with Peter Stuyvesant, director-general of New Netherland.

Ruling from a stub of Lower Manhattan that ended at Wall Street, Stuyvesant “ordered enslaved Africans to build a nine-mile road from lower Manhattan to the city known then as Nieuw Haarlem,” states a blog post by Sylviane A. Diouf from the New York Public Library.

Calling Harlem a city might be a stretch; Harlem would remain a sparsely populated community for its first few hundred years, as seen above in the mid-1800s.

As for the people tasked with building the road: Enslaved Africans had been a part of New Amsterdam since 1626, and over the decades many became free citizens. The New Amsterdam History Center estimates that the colonial outpost’s population circa 1660 had about 1,500 residents. Of that number, 375 people of African descent were free; 75 were enslaved.

Seven years after the road was completed, “the residents erected the First Reformed Low Dutch Church of Harlem (future Elmendorf Reformed Church) at First Avenue and 127th Street and a quarter acre of land was reserved for a ‘Negro Burying Ground,'” states the NYPL blog post.

New Yorkers of European and African descent (no longer enslaved as of 1827, per a state law that banned slavery) continued to be buried in separate sections of the cemetery until the middle of the 19th century. Harlem was still overwhelmingly rural, but urbanization was on the horizon.

“In the mid-1800s, prompted by the northward expansion of the city, the land the Harlem African Burial Ground sat on was sold,” states the website for the New York City Economic Development Corporation (NYCEDC). The remains of those interred in the white cemetery were moved in the 1860s and 1870s to Woodlawn Cemetery, per the NYPL blog post.

At this point, a popular destination was built on top of the burial ground: the Harlem Casino, also known as Sulzer’s Harlem River Park (above, on the map). This amusement park and beer garden built in 1885 overlooked the Harlem River and offered rides, games, and the kind of rowdy, day-trip escape working-class New Yorkers indulged in during the Gilded Age.

Sulzer’s burned down in 1907, and the land was then used as a movie studio, according to the New York City Cemetery Project. The Elmendorf Reformed Church, the successor to the church that founded the burial ground, built a new chapel on 121st Street around 1910 (above). The bus depo was completed in 1947.

Though the burial ground had largely been forgotten, historians and community members who had documented proof of its existence began rallying the city in the early 2000s to create a memorial on the site, per the NYCEDC website. After the MTA decommissioned the bus depot, archeologists were brought in to investigate.

In 2015, more than 140 bones and bone fragments had been discovered. “Most compelling of all was a skull, its cranium intact, that most likely came from an adult woman of African descent,” wrote David W. Dunlap in a 2016 New York Times piece.

“These human remains were not situated in their original burial locations and were not within an identifiable burial shaft or grave, but were instead disarticulated, meaning they were separated from the other bones of the same body,” states the NYCEDC website.

Another phase of archeologic investigation to uncover more remains reportedly happened last year, and members of the Harlem African Burial Ground Initiative are considering how to memorialize the site and the people interred there—who, as the NYPL blog post put it, “still rest under the concrete, the pipes and the earth.”

[Second image: NYPL Digital Collections; third image: NYPL Digital Collections; fourth image: Wikipedia]

February 23, 2025

A rich family abandons their Gilded Age brownstone on Madison Square, its contents not revealed until the 1940s

Almost every New York City neighborhood has one—a mysteriously abandoned house.

Residents are never seen coming or going through its doors, and the unkept exterior and overgrown yard, not to mention the boards over the doors and windows, raise eyebrows. Neighbors talk, rumors swirl, but no one really knows why the house was left alone.

In the first decades of the 20th century, that abandoned house would have been 22 East 23rd Street (above), a formerly elegant brownstone in a row of beauties built before the Civil War for the Colgate family.

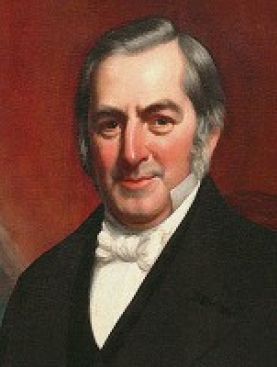

Recognize the name? That’s Colgate as in Colgate-Palmolive and Colgate University. William Colgate (below) founded his soap, starch, and candle concern two years after arriving in New York as an English immigrant in 1804 and apprenticing with a soap boiler.

Headquartered at 4-6 Dutch Street, the company grew—thanks to hot products like “cashmere bouquet” scented soap, as well as formulations such as “toilet essence” and “pearl starch,” according to the Encyclopedia of New York City.

By the mid-19th century, Colgate was rich and influential—an ardent Baptist who worshipped at the Baptist Tabernacle Church on Second Avenue and 11th Street, which he reportedly contributed the funds to help build.

He and his wife, Maria, moved with their children to their new brownstone mansion at 22 East 23rd Street in 1851. After their daughter Mary married a few years later, Mary and her new husband moved in to the brownstone and shared it with her parents.

It was a befitting new neighborhood for this prominent family. Officially made a city park in 1847, Madison Square was becoming the center of the most exclusive residential enclave in New York—close in proximity to theaters and shopping but with the peace and privacy of a well-manicured park as a buffer.

“The unique location where Madison Avenue begins afforded the family an uninterrupted view up the Avenue as well as a prestigious place on the park,” wrote Miriam Berman in Madison Square: The Park and Its Celebrated Landmarks.

William Colgate didn’t live long in his East 23rd Street house. He died in 1857, after his wife had passed away in 1855. Both reside now in Green-Wood Cemetery.

Through the next several decades, various descendants of the family occupied the brownstone—seemingly still lovely but no longer in a fashionable neighborhood. Madison Square Garden, the Fifth Avenue Hotel, and other businesses made the enclave more commercial. (Below, from the window of the Colgate house in 1883, looking up Madison Avenue.)

The last occupant, according to one newspaper account, was William Colgate’s grandson, William Colgate Colby, who was born inside the house in 1858. Colby, a Yale graduate, seems to be the family member who walked away from what was described as the “sole remaining private residence on Madison Square.”

That happened in 1911, according to one news story. “The legend tells that when his wife died, twenty-five years ago, Colby walked out of the brownstone structure, turned the key in the lock, and thereafter left the house unoccupied—with furniture, books, and clothes untouched from that day on,” reported the newspaper in 1934.

“Colby used to come down twice a year from his New Hampshire retirement, and on those occasions his short, square-set figure would be seen entering or leaving the silent house,” the newspaper continued. “But no one ever lived in the place, and the tightly sealed shutters were never once removed from the windows or doors.”

William Colgate Colby died in 1936, but the full story of the mystery mansion didn’t appear until 1944. That’s when William Colgate Colby’s sister, Jessie Colgate Colby, decided to sell the house to a developer who intended to put up a one-story taxpayer.

Berman’s account has the brownstone abandoned in 1918. “For 27 years the house and its contents stood untouched, visited only on occasion by a guard to check the burglar alarm,” she wrote. “Upon its sale, boards were removed from its entrance and its French windows were opened wide.”

In 1945, four floors of furnishings and personal items frozen in time from the Gilded Age were up for sale. “Thousands of people on the street who passed the house stopped to gape at the ancient brownstone that had once been one of the finest homes on Madison Square,” wrote Berman.

“The crowds peered through the dusty parlor windows at the elegant objects of a Victorian past, covered with at least six inches of dust,” continued Berman. “There were gold chandeliers, marble columns, elaborately carved gilt-framed mirrors, paintings, and mahogany furniture.”

Artifacts from the 19th century included a rosewood piano (above), two gold harps, volunteer fire department helmets, ostrich plumes, waistcoats, crimping pins, and leghorn hats, according to a 1945 Philadelphia Inquirer report.

“Just as the sleeping palace might have remained unchanged year after long year, so the Colgate mansion was exactly as it had been in the summer of 1918 when the last of the family stepped across the threshold and rode away,” wrote the Inquirer.

“Beds were neatly made beneath blankets of dust; towels hung over the old-fashioned wash stands. Writing paper and pens were ready on the desks. Great cedar closets were hung with the hobble-skirted, pointy-shoe styles popular at the beginning of the First World War.”

Antique dealers were admitted inside to pick through the objects and take what was valuable. Onlookers were able to glimpse pieces as they were carted away.

One onlooker stated that he had been a friend of William Colgate, and he recalled how Colgate told him about “the happy evenings he spent in this house,” wrote Berman, adding that the now-empty brownstone at 22 East 23rd Street sold for less than its assessed value of $77,000. The taxpayer building that went up now houses a McDonald’s (above).

The “mystery mansion of Madison Square” (above, with the ivy, in an undated photo), as newspapers dubbed it, would hardly be the city’s last abandoned property.

But considering the furniture and personal effects left exactly as the family kept them for decades, wouldn’t it have been wonderful if the house was preserved as a living museum of the Antebellum era and Gilded Age?

[Top image: NYC Department of Records & Information Services; second image: Made Up in Britain; third image: NYPL Digital Collection; fourth image: Valentine’s Manual of Old New York; fifth image: NYC Department of Records & Information Services; sixth photo: Philadelphia Inquirer; seventh photo: undated, from Miriam Berman’s Madison Square: The Park and Its Celebrated Landmarks]

February 17, 2025

From elite club to speakeasy, the early life of an ornate house called a “hot-air balloon of masonry”

When 721 St. Nicholas Avenue (below, corner house) made its debut in 1891, the formerly sleepy village of Harlem was rapidly becoming part of the urban streetscape.

What had been a rural area dotted with estate houses in the 18th century (like Alexander Hamilton’s country retreat, the Grange) became a popular place for wealthy New Yorkers to enjoy harness racing by carriage or sleigh after the Civil War.

That was due to the official opening of St. Nicholas Avenue—a broad, 80-block boulevard running from about Central Park to the wilds of Upper Manhattan. Before it was widened into St. Nicholas Avenue, the road was known as Harlem Lane (third image).

In the 1880s, however, developers arrived, hoping to capitalize on St. Nicholas Avenue’s carriage and trotter cache. One of these developers snapped up land stretching to the corner of 146th Street and hired an architect to design five row houses.

Described as “Victorian Romanesque” by the Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) in a 2000 historic designation report, the first four row houses, Numbers 713 to 719, were splendid confections of brownstone and brick turrets, gables, and dormers.

But the real showpiece was Number 721. Larger than its sister houses, it featured a curved tower with a flat roof, plus what the LPC report described as a “mansard roof with slate tiles,” “dormer with scrolled gable,” and a “paneled, brick parapet.”

Some would describe this house as storybook-like, something mysterious and delightful from a fairy tale. Others found it pretentious, like Christopher Gray, who called it “bulbous” and a “hot-air balloon of masonry” in a 2009 New York Times column.

Both descriptions might fit. But in the Gilded Age, when home-buyers sought out Queen-Anne style row houses with lots of decorative doo-dads, 713-721 St. Nicholas Avenue would have commanded attention. These would be white home-buyers, as Harlem’s transformation into the center of African American life in New York was a few decades away.

Who occupied Number 721 on the corner? The first residents in its earliest days are unclear. But by 1898, the house was purchased by an organization called the Heights Club, a “newly formed club” composed of upper-class residents who held an inaugural “smoker” in March 1898 where images viewed through a stereoscope made for the entertainment.

By the early 1900s, the Heights Club was gone, replaced by the Barnard School, a boys’ college preparatory school. The school held sports events called the Barnard School Games at the Kingsbridge Armory and invited other schools to compete.

When the Barnard School departed is a mystery. But in 1925 with Prohibition the law of the land, the ground floor of Number 721 transformed into a speakeasy. The Silver Dollar Cafe was considered one of the first speaks in this part of Harlem, now known as Hamilton Heights or Sugar Hill, according to the LPC report.

The Silver Dollar Cafe “became the Seven-Two-One Club following Prohibition,” per the LPC report. “The spot featured local jazz talent, such as the Kaiser Marshall Trio, Harlem Harley’s Washboard Band, and the Ernie Henry Band.” The space operated until 1964. (Below, in 1940)

In the ensuing years, numbers 713-717 have had commercial spaces installed on the ground floor, replacing the stoops. That, along with the alteration of other original details, made for the loss of “the genteel appearance with which they faced the carriages and sleighs of the avenue,” wrote Gray.

What’s next in the life of Number 721? It looks like this storybook survivor has been marketed as a condo building with five separate units, according to a Streeteasy description.

Imagine what it would be like making your home here and feeling the phantoms of the trotters, club-goers, schoolboys, secret drinkers, and jazz trios who occupied this space in its earliest, most colorful years.

[Third image: NYPL Digital Collections; fifth image: MCNY F2011.33.193; sixth image: NYC Department of Records & Information Services]

February 16, 2025

The unmarked Harlem grave of one of Revolutionary War-era America’s first spies

Walk along Broadway at about 116th Street, and you’ll come across a bronze tablet on the facade of a Columbia University building.

The tablet shows a dramatic Revolutionary War battle scene: A Continental Army leader stands on a rock outcropping, raising his sword defiantly with the British at his back. Below him, another American fighter lies mortally wounded on the ground, clutching his chest.

As the tablet explains, the bas relief depicts a scene from the Battle of Harlem Heights—in which George Washington’s forces pushed back the invading British in a buckwheat field on today’s Columbia campus.

The Battle of Harlem Heights happened weeks after the bruising defeat of the Battle of Brooklyn, and this small victory in the rural countryside of Harlem raised the morale of the Patriots in a big way.

But the victory may not have happened without the assistance of Thomas Knowlton (at left)—the commander considered one of America’s first spies who raises his sword in the tablet.

Who was Thomas Knowlton? Brought up in Connecticut, Knowlton was 15 when he served in the French and Indian War. As the Revolutionary War broke out in 1775, he joined a militia that fought the Battle of Bunker Hill.

Promoted to lieutenant colonel, he and 150 select New England soldiers marched to New York in August 1776 at the behest of George Washington to serve as “an elite company for conducting reconnaissance mission behind enemy lines,” according to Spy Sites of New York City: Two Centuries of Espionage in Gotham.

Knowlton’s Rangers, as the company was known, were tasked with scouting the movement of British forces, who had come to Manhattan at Kip’s Bay and were making their way to the rocky, hilly terrain of Upper Manhattan, where American forces had amassed.

Knowlton’s espionage skills have led historians to designate him as the father of military intelligence. “These men undertook the dangerous task of obtaining intelligence information for the Continental army,” notes Connecticuthistory.org. “Included among Knowlton’s troops was the soon-to-be-famous patriot Nathan Hale.”

But even an elite and experienced colonel like Knowlton (above, in a statue at the Connecticut state capitol) was vulnerable. On September 16, “Knowlton’s men undertook a reconnaissance mission that brought them into direct contact with the British army,” states Connecticuthistoryorg.

“Knowlton engaged the British in battle in an effort to prevent them from pursuing the fleeing Continental army up Manhattan Island. Knowlton’s men suffered heavy casualties, including Knowlton himself, whose life was ended by a fatal shot to the back.”

Washington acknowledged the loss by writing in his General Orders, “The gallant and brave Col. Knowlton, who would have been an Honor to any Country, having fallen yesterday, while gloriously fighting….”

Like other fallen soldiers, Knowlton was reportedly buried on her near the battlefield—in this case, in the middle of today’s urbanized Harlem.

According to the Connecticut Society of the Sons of the Revolution, Knowlton’s body was laid to rest “with military honors” in an unmarked grave that would correspond with today’s St. Nicholas Avenue and 143rd Street—two roads that didn’t exist at the time.

There actually is no St. Nicholas Avenue and 143rd Street, as 143rd Street temporarily ends at Convent Avenue to the west and begins again at Bradhurst Avenue. But where Knowlton’s body is supposedly buried might be in the fifth and sixth photos, taken from St. Nicholas Avenue.

It would be almost impossible to definitively know if Knowlton’s remains lie here. But perhaps another plaque at this site could explain the story of the unmarked grave—and the American spy who died nearby for liberty and independence.

[Top image: Wikipedia; second image: Wikipedia; third image: NYPL Digital Collections; fourth image: Wikipedia]

February 10, 2025

When subway signs spell simple words wrong

This is not a new photo, nor am I sure what station we’re at. But I do know that someone tasked with proofreading subway signs before they’re installed made a big error.

Unless “dowtown” is a new hip neighborhood name I’m not aware of? Thank you Andrew Alpern for sending me this image…one of many I’ve posted of MTA spelling errors.

This post shows a photo of a subway entrance for “Bleeker Street” on the 6 train. Not to be outdone are the people responsible for street names—see the photo for “Merser Street” at West Houston!

The problem with the enormous “sun towers” that illuminated Madison Square Park in the 1880s

The first street lights to illuminate New York City came from home oil lamps. In 1697, the Common Council mandated “that all and every of the house keepers within this city shall put out lights in their windows fronting ye respective streets,” according to a 1997 Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) report.

In 1762, oil lamps were installed on city streets, with watchmen paid to oversee them. By the 1820s, gas-lit, cast-iron street lamps gave off their weak, smelly glow while lighting the way along New York’s expanding roadways, per the LPC report.

But in 1880, a new type of light was ready to replace the gas lamp: electric light. That year, the Brush Electric Light & Power Company built Manhattan’s first arc street lamps along Broadway between 14th through 26th Streets (above illustration).

But the Brush people had another idea: illuminating Madison Square with massive arc lamps that were dubbed “sun towers.”

“At the top of a mast of 160 feet was a circular carriage, to which were attached enormous electric lamps of 6,000 candlepower each,” wrote Miriam Berman in her 2001 book, Madison Square: The Park and Its Celebrated Landmarks.

The goal of so much light was to illuminate the park and surrounding streets, which in the Gilded Age were the heart of Gotham’s theater and shopping district. What could go wrong with powerful bright light to guide people on their way?

Plenty. “Unfortunately, they were almost blinding to people standing nearby, and the ladies complained that they appeared almost ghostly in this bright light,” wrote Berman.

A Brooklyn Daily Times article agreed. Arc light “hurts the eyes by its constant flicker and emits a ghastly, blueish light that is the reverse of pleasant,” the newspaper reported.

I couldn’t find out when these giant showers of light were removed from Madison Square Park. But arc street lamps continued to be in use through the 1910s, per the LPC report, when improvements to incandescent light put an end to the arc-lamp era on New York’s streets.

[Top image: Scientific American, 1881; second image: Wikipedia]

This former schoolhouse built in 1849 in Chelsea is a remnant of New York’s segregated past

It’s a pale yellowish stub of a building on West 17th Street—just three stories high and sheared of any decorative embellishments it had when it was built in pre-Civil War New York City.

But if you look closely, you’ll see some unique features. The top two floors have four multi-paneled windows rather than the typical three. And two identical separate entryways on the ground level seem excessive; for such a small building, one doorway should do.

These features are clues that 128 West 17th Street wasn’t built as a home or commercial structure. As unlikely as it seems, it was originally a schoolhouse. The long windows allowed plenty of light to reach children in their classrooms, and the two doorways would have been the separate entrances for girls and boys.

It’s amazing enough that a school building still exists in today’s Chelsea 175 or so years after it opened, especially since no state law mandated that children even attend school until 1874.

But what makes this little schoolhouse so remarkable is that it spent most of its early decades as a public city “colored school”—one of eight separate, segregated grammar schools in Manhattan for African-American kids. (Below, the school in 1908)

“Colored School No. 4,” as it was known for most of its life, was constructed in 1849-1850 by the Public School Society. Though wealthy families relied on private schools and tutors to educate their kids, working-class and poor children were on their own.

The Society—formed in 1805 by city leaders and with roots in the abolitionist-led Free African School organization of the late 18th century—took on the responsibility of creating free public schools throughout Manhattan.

When it first opened its doors in what was a working-class enclave of modest row houses in the rapidly developing Chelsea neighborhood, this primary school served local kids whose families were English, Scottish, German, French, Italian, or Irish, according to a 2023 report from the Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC).

The Public School Society merged with the newly created Board of Education in 1853. By 1860, 128 West 17th Street became a Black primary school—first called Colored School No. 8 and then Colored School No. 4.

“By 1860 many African Americans, who were often limited to where they were able to live, settled the West Side of Manhattan from 10th to 30th streets, and the school reflects this history,” notes the LPC report.

That 19th century New York had a legally segregated school system isn’t well-known; we tend to think of Gotham as a city that has long welcomed people from all backgrounds, at least on paper.

But other facets of city life were also segregated at the time, like hotels, churches, and even streetcars. The end of mass transit segregation was prompted by one fed-up Black rider named Elizabeth Jennings, who pushed back against the Third Avenue Railway Company and won her case in court in 1854 (with help from her lawyer, future president Chester Arthur).

Colored School No. 4 may have been segregated, but that didn’t seem to affect the dedication of the staff. The school was led by Sarah Tompkins Garnet, a pioneering educator and suffrage supporter who came from a Brooklyn farming and merchant family. Garnet was one of the first Black women to become principal of a city school, per the LPC report.

But the school wasn’t immune from racism. During the Draft Riots of July 1863, a mob surrounded the school and tried to break in while students and teachers were inside. “It seemed that two colored women whom they had pursued had taken refuge in the school-building, and they were determined to get at them,” reported the New-York Tribune on July 15.

“The teachers promptly barred all the doors leading into the street,” the newspaper wrote (above). The rioters moved on, turning their attention to a house across the street.

“Later that day, [Garnet] escorted many of the schoolchildren safely to their homes through the dangerous streets before heading to her own home in Brooklyn,” wrote John Freeman Gill in a 2022 New York Times article.

The end of city-endorsed school segregation came in 1883, states the LPC report, and Colored School No. 4 was renamed Public Grammar School 81. By 1894, it was shuttered. Garnet remained school principal until the end.

In the early 1900s, the schoolhouse was leased to a veteran’s association, then underwent a renovation in the 1930s that removed its cornice and added the brick facade.

Still city-owned, it was used by the Sanitation Department as a lunchroom until about a decade ago, according to Gill’s 2022 Times article. (Fifth photo: the school in 1940)

A campaign to acknowledge the school’s place in New York City history, led by historian Eric K. Washington, resulted in landmark status for the building. Right now, 128 West 17th Street is undergoing a much-needed renovation.

While it’s getting rehabbed, the little schoolhouse on a Chelsea sidestreet stands as a remnant of New York’s backstory that’s been mostly forgotten.

[Third image: Real Estate Owned by the City of New York; fourth image: Directory of the Board of Education of the City and County of New York; fifth image: NYC Department of Records & Information Services; sixth image: New-York Tribune July 1863; seventh image: Wikipedia]