Esther Crain's Blog, page 53

March 14, 2022

A Gilded Age chateau on Madison Avenue, and the old-money owner who never moved in

When the Gilded Age began after the Civil War, brownstone mansions were all the rage. By the early 1900s at the end of the Gilded era, Beaux-Arts became the architecture of choice among those New Yorkers wealthy enough to afford it.

Gertrude Rhinelander Waldo chateau, today

Gertrude Rhinelander Waldo chateau, todayBut houses of another design style also began to rise during the Gilded Age: French chateaux. These Gothic stone fortresses on Fifth Avenue, Madison Avenue, and Riverside Drive were built with dormers, turrets, spires, and other bells and whistles inspired by Medieval castles and the imaginations of people using real estate to outdo each other.

Perhaps the most famous chateau was constructed in 1882 at Fifth Avenue and 53rd Street: the William K. Vanderbilt mansion—called “petite chateau” by Alva Vanderbilt, W.K.’s social-climbing wife. A year later, W.K.’s brother, Cornelius Vanderbilt, built an even more ostentatious chateau-like mansion at Fifth Avenue and 57th Street.

An illustration from 1897, soon after the mansion was completed

An illustration from 1897, soon after the mansion was completedSo when Gertrude Rhinelander Waldo (below) purchased land on the southeast corner of Madison Avenue and 72nd Street in 1882 and finally commissioned an architect to go ahead and build her own chateau in 1894, according to Christopher Gray in the New York Times, she may have looked to the Vanderbilt mansions for inspiration. (Supposedly she said she modeled her house after a chateau she admired on a visit to France.)

Mrs. Waldo may not be remembered as a major player during the Gilded Age, but she was certainly known in her era. Born in 1842, she was a descendant of the aristocratic Rhinelander family. Like other old-money daughters at the time, she married and had a child (future police and fire commissioner Rhinelander Waldo). In 1878, she was widowed.

Mrs. Gertrude Rhinelander Waldo

Mrs. Gertrude Rhinelander WaldoDescribed as a “very pretty woman” by one newspaper and a woman “of forceful manner and some unusual views” by another, she lived with her sister across 72nd Street while the chateau was under construction. Madison Avenue at the time was no Fifth Avenue, but it was filling up with mansions for the rich and distinguished. At this intersection Louis Comfort Tiffany had a house, and so did W.K. and Alva Vanderbilt’s daughter, Consuelo, who had just married the Duke of Marlborough.

Said to have cost her $500,000, Mrs. Waldo’s house had a fourth floor ballroom lit by 2,000 electric lights and a basement bowling alley, according to a 1918 article in the Evening Post. A New York Times piece in 1909 reported that the house also had a billiards room, electric elevator, a library, and curiously only two rooms for servants, “yet the proper running of a house of this character would require from 10 to a dozen servants,” the paper wrote.

The unoccupied mansion in 1912

The unoccupied mansion in 1912You would think that Mrs. Waldo would be thrilled to relocate to her new home once it was completed around 1895. After all, it was designed to her specifications, and she’d purchased cases of tapestries, marble, glass, and china to furnish the house with, per the Evening Post.

But when it came time to move in, she never did; she remained at her sister’s home across the street. And no one was sure why.

As the years went on, the house remained empty. Reportedly Mrs. Waldo put it up for sale several times, only to walk away and change her mind when a deal was close. It’s not known what kept her from occupying the chateau, but her fortunes likely took a dive. Even so, the old-money heiress and her empty chateau became something of a fascination to the public.

“The Waldo mansion at the southeast corner of Madison Avenue and 72nd Street, a house with many bathrooms, and other features that have made it the subject of considerable mention in print and gossip, but distinctive among New York City homes, because it was never occupied….” stated the Evening Post.

The New York Times in 1909 described it as “one of the curiosities in real estate circles.” The house, “has been in a state of semi-dilapidation for many years. The once fine stone front is badly discolored, and the accumulated storms of a dozen years have damaged the interior fittings, the rain soaking through the great dome in the roof, and percolating through cracks and crevices, to an amount estimated as many thousands of dollars.”

The chateau in 1897

The chateau in 1897For years, the empty house with rich unpacked furnishings became prey to burglars. Finally in 1909, the house went into foreclosure and was sold at auction. But it wasn’t until the 1920s when the chateau was carved into apartments and the ground floor turned into commercial space.

When Mrs. Waldo died in 1914 in her home in the Netherland Hotel (forerunner to the Sherry-Netherland), she was 73 years old and in debt, it was revealed. What would this socialite heiress think if she knew Ralph Lauren would purchase and renovate her chateau in the 1980s and make it the flagship location for his fashion brand—which conjures up old money and luxury?

[Second image: NYPL; third image: The Clio; fourth image: New-York Historical Society; sixth image: NYPL]

March 13, 2022

A ghostly store sign returns to view on Avenue B

Humble, homemade-looking store signs used to be more prevalent in Manhattan. Now, one of these unadorned signs—for an unbranded cosmetics and gift shop—is back in view at the tenement storefront at 205 Avenue B.

Nothing about this former store seems to exist in archives or old neighborhood photos, making the sign a ghostly remnant of a very modest-looking local business.

How far back in East Village history does this sign go? I’m not sure, but the store may have been selling makeup and gifts up until about 40 years ago. The sign reappeared sometime after Raul Candy Store closed in 2019, 38 years after setting up shop at 205 Avenue B in 1981, per EV Grieve.

h/t: Ghost Signs NYC

March 7, 2022

The teens who found splendor on the gritty East Side docks of the 1940s

The smokestacks and storage tanks of the East River waterfront of the 1930s or 1940s should be an unappealing place to meet friends. But painter Joseph Lambert Cain has captured a group of teenagers gathered on a pier here to sunbathe, talk, and pair off.

For these teens, perhaps from the Lower East Side or the Gas House District in the East 20s, the waterfront is an idyllic location—away from the critical eyes of adults and into the warm embrace of the working class city they likely grew up in.

Cain titled his painting “New York Harbor.” I’m not sure of the date, but my guess is about 1940. The riverfront industry surrounds them, but the modern city of skyscrapers is within sight and reach.

A stunning Gilded Age mansion on Riverside Drive—and the tabloid drama of its first owners

If you’re keeping up with HBO’s The Gilded Age, you might conclude that New York’s richest families of the era only lived on Fifth Avenue. There’s some truth to this, as old and new money New Yorkers with names like Astor and Vanderbilt built fancy fortresses for themselves on this premier avenue south and east of Central Park.

330 Riverside Drive, aka the Davis Mansion

330 Riverside Drive, aka the Davis MansionBy the turn of the century, however, another millionaire mile in Manhattan was giving Fifth Avenue a run for its money. Riverside Drive was booming with spectacular mansions mostly of the then-popular Beaux-Arts style—some elegant row houses; others stand-alone palaces with sloping yards and river views. (No brownstones, which were entirely out of fashion.)

Riverside Drive never did overtake Fifth Avenue as the city’s millionaire colony. It was too far from the action at Delmonico’s, the Metropolitan Opera House, and the elite hotels and clubs where business was done and deals were made. (It also didn’t have the same kind of foot traffic as Fifth, and what was the point of living on a street where you couldn’t see and be seen by those who mattered in society?)

Still, plenty of rich New Yorkers lived well in these new Riverside Drive mansions in the early 20th century. One stunning house that looks like it belongs in the Belle Epoque still stands at 330 Riverside Drive, on the corner of 105th Street (above).

This five-story Beaux-Arts beauty that fronts 105th Street and also overlooks a narrow stretch of Riverside recalls “a great Parisian mansion,” according to the Riverside-West 105th Street Historic District Designation Report from 1973. The same builder of 330 also put up numbers 331, 332, and 333 Riverside—three slender, harmonious, equally expensive row houses.

Completed in 1902, this example of light brick and limestone loveliness features a “richly ornamented recessed doorway,” decorative balconies, dormer windows, “three tiers of triple windows,” a mansard roof, and a one-story “conservatory” (above) on the east side of the mansion, per the Historic District Report.

It’s a knockout for sure. But the beauty of the mansion belies the unsavory story of a Gilded Age tycoon and his wife, who were the first occupants. You know this businessman—or at least you know his name, which is emblazoned on the product he packaged in a red and orange cylinder and is still sold in supermarkets everywhere.

Lucretia Davis, Jennie Davis, and Jennie’s divorce lawyer, Delphin M. Delmas

Lucretia Davis, Jennie Davis, and Jennie’s divorce lawyer, Delphin M. DelmasRobert Benson Davis, a Civil War veteran who fought for the Union, was the man behind Davis Baking Powder, which he began manufacturing around 1880. The product made him a fortune and earned him the name “baking powder king.” (Interestingly, at 176 Riverside lived John H. Matthews, known as the “soda water king” for manufacturing soda fountains.)

Davis moved into the mansion in 1905 with his wife Jennie (who he married when he was 38 and she just 18 years old), and their adult daughter, Lucretia. Perhaps it was their age difference, or maybe the corrupting influence of money. But this was an unhappily married couple. Davis left for Los Angeles, where he sued his wife for divorce in 1910.

330 Riverside Drive in 1925

330 Riverside Drive in 1925The allegations about their marriage were perfect for the tabloid era. According to Daniel J. Wakin, author of the lively book The Man With the Sawed-Off Leg and Other Tales of a New York City Block, “Davis charged that Jennie tried to have him declared insane so she could seize his business, accusing her of telephoning executives of the company to say he was losing his mind. She intercepted his mail while keeping him trapped in his house under the surveillance of nurses.”

Davis also alleged that Jennie held him captive in the house. “Once, he said he dropped a letter to a friend from a fourth-floor window, asking for help,” wrote Wakin. “The friend sent a car, and Davis said he slipped out when the servants were distracted by clearing his dinner dishes, and headed for another home he owned, in Summit, New Jersey.”

The mansion in roughly 1940

The mansion in roughly 1940Of course, the affair Davis supposedly had with his nurse didn’t help his case. Jennie hired the same lawyer who helped get Harry K. Thaw a not-guilty-by-reason-of-insanity verdict at Thaw’s infamous trial for shooting Stanford White on the roof of Madison Square Garden in 1906.

Jennie was awarded some financial support and remained at 330 Riverside with Lucretia. She appealed the divorce case for years, seeking a bigger financial settlement, until she unexpectedly died in 1915.

330 Riverside Drive facing Riverside Drive

330 Riverside Drive facing Riverside DriveDavis died five years later. Lucretia and her husband (who took over the Davis Baking Powder company) inherited the mansion. They lived in it together until the husband passed away in 1951. Lucretia held on, then left the house. At the time, some of the other mansions on Riverside had been carved up into apartments or rooming houses, and the elite feel of the area took a downward turn.

Number 330 may have survived so long because of the Roman Catholic order that purchased the mansion and turned it into a school. Today, Opus Dei occupies the house, according to Wakin. It’s an outpost of quiet and peace more than a century after the bitter divorce and tawdry allegations of the original homeowners.

[Fourth photo: Los Angeles Herald, 1911; fifth photo: NYPL; sixth photo: NYC Department of Records and Information Services]

The story of a Gilded Age mansion’s unhappily married owners on Riverside Drive

If you’re keeping up with HBO’s The Gilded Age, you might conclude that New York’s richest families of the era only lived on Fifth Avenue. There’s some truth to this, as old and new money New Yorkers with names like Astor and Vanderbilt built fancy fortresses for themselves on this premier avenue south and east of Central Park.

330 Riverside Drive, aka the Davis Mansion

330 Riverside Drive, aka the Davis MansionBy the turn of the century, however, another millionaire mile in Manhattan was giving Fifth Avenue a run for its money. Riverside Drive was booming with spectacular mansions mostly of the then-popular Beaux-Arts style—some elegant row houses; others stand-alone palaces with sloping yards and river views. (No brownstones, which were entirely out of fashion.)

Riverside Drive never did overtake Fifth Avenue as the city’s millionaire colony. It was too far from the action at Delmonico’s, the Metropolitan Opera House, and the elite hotels and clubs where business was done and deals were made. (It also didn’t have the same kind of foot traffic as Fifth, and what was the point of living on a street where you couldn’t see and be seen by those who mattered in society?)

Still, plenty of rich New Yorkers lived well in these new Riverside Drive mansions in the early 20th century. One stunning house that looks like it belongs in the Belle Epoque still stands at 330 Riverside Drive, on the corner of 105th Street (above).

This five-story Beaux-Arts beauty that fronts 105th Street and also overlooks a narrow stretch of Riverside recalls “a great Parisian mansion,” according to the Riverside-West 105th Street Historic District Designation Report from 1973. The same builder of 330 also put up numbers 331, 332, and 333 Riverside—three slender, harmonious, equally expensive row houses.

Completed in 1902, this example of light brick and limestone loveliness features a “richly ornamented recessed doorway,” decorative balconies, dormer windows, “three tiers of triple windows,” a mansard roof, and a one-story “conservatory” (above) on the east side of the mansion, per the Historic District Report.

It’s a knockout for sure. But the beauty of the mansion belies the unsavory story of a Gilded Age tycoon and his wife, who were the first occupants. You know this businessman—or at least you know his name, which is emblazoned on the product he packaged in a red and orange cylinder and is still sold in supermarkets everywhere.

Lucretia Davis, Jennie Davis, and Jennie’s divorce lawyer, Delphin M. Delmas

Lucretia Davis, Jennie Davis, and Jennie’s divorce lawyer, Delphin M. DelmasRobert Benson Davis, a Civil War veteran who fought for the Union, was the man behind Davis Baking Powder, which he began manufacturing around 1880. The product made him a fortune and earned him the name “baking powder king.” (Interestingly, at 176 Riverside lived John H. Matthews, known as the “soda water king” for manufacturing soda fountains.)

Davis moved into the mansion in 1905 with his wife Jennie (who he married when he was 38 and she just 18 years old), and their adult daughter, Lucretia. Perhaps it was their age difference, or maybe the corrupting influence of money. But this was an unhappily married couple. Davis left for Los Angeles, where he sued his wife for divorce in 1910.

330 Riverside Drive in 1925

330 Riverside Drive in 1925The allegations about their marriage were perfect for the tabloid era. According to Daniel J. Wakin, author of the lively book The Man With the Sawed-Off Leg and Other Tales of a New York City Block, “Davis charged that Jennie tried to have him declared insane so she could seize his business, accusing her of telephoning executives of the company to say he was losing his mind. She intercepted his mail while keeping him trapped in his house under the surveillance of nurses.”

Davis also alleged that Jennie held him captive in the house. “Once, he said he dropped a letter to a friend from a fourth-floor window, asking for help,” wrote Wakin. “The friend sent a car, and Davis said he slipped out when the servants were distracted by clearing his dinner dishes, and headed for another home he owned, in Summit, New Jersey.”

The mansion in roughly 1940

The mansion in roughly 1940Of course, the affair Davis supposed had with his nurse didn’t help his case. Jennie hired the same lawyer who helped get Harry K. Thaw a not-guilty-by-reason-of-insanity verdict at Thaw’s infamous trial for shooting Stanford White on the roof of Madison Square Garden in 1906.

Jennie was awarded some financial support and remained at 330 Riverside with Lucretia. She appealed the divorce case for years, seeking a bigger financial settlement, until she unexpectedly died in 1915.

330 Riverside Drive facing Riverside Drive

330 Riverside Drive facing Riverside DriveDavis died five years later. Lucretia and her husband (who took over the Davis Baking Powder company) inherited the mansion. They lived in it together through the early 1950s, after some of the other mansions on Riverside had been carved up into apartments or rooming houses, and the elite feel of the area took a downward turn.

Number 330 may have survived so long because of the Roman Catholic order that purchased the mansion and turned it into a school. Today, Opus Dei occupies the house, according to Wakin. It’s an outpost of quiet and peace more than a century after the bitter divorce and tawdry allegations of the original homeowners.

[Fourth photo: Los Angeles Herald, 1911; fifth photo: NYPL; sixth photo: NYC Department of Records and Information Services]

February 28, 2022

The favorite way the Gilded Age elite enjoyed Central Park in the 1860s

Central Park was conceived as a respite from the noise and pollution of the industrial city—a tranquil landscape where New Yorkers could relax and refresh in a natural environment.

But in the first years of the park’s existence in the 1860s, it was the wealthy who enjoyed it the most. After all, in the early Gilded Age, they were the ones who had the leisure time to spare and the vehicles to bring them to this green space far from the center of the city.

So how did they use the park? By driving—or being driven. With fancy carriages and a coachman or two handling the road, New York ladies and gentlemen spent late afternoons traversing the park’s many drives. Sometimes a Gilded Age sportsman would take the reins on his own trotting horse.

“Another notable feature of former days was the driving in Central Park,” according to the book Fifth Avenue, from 1915. “Here might be seen old Commodore Vanderbilt, driving his famous trotter, ‘Dexter’; Robert Bonner, speeding ‘Maude S.’; Thomas Kilpatrick, Frank Work, Russell Sage, and other horsemen driving to their private quarter- or half-mile courses in Harlem; leaders of society or dowagers in their gilded coaches; and even maidens of the ‘Four Hundred’ driving their phaetons.”

[Image: Currier & Ives after Thomas Worth]

A Herald Square faded ad for a haberdashery takes you to the 1920s

When Weber & Heilbroner moved into the Marbridge Building at 34th Street and Sixth Avenue in 1923, this men’s clothing company had already established itself as a leading haberdashery—with stores throughout Manhattan and Brooklyn, according to the Brooklyn Daily Eagle earlier that year.

Could this enormous faded ad looming over Sixth Avenue for the Marbridge store date back that far?

It’s hard to believe, but it certainly is appropriately faded and has an old-timey feel, with the words under the company name reading “Stein-Bloch Clothes in the New York Manner.” (Stein-Bloch was a manufacturer of men’s suits and coats.)

Weber & Heilbroner stores shut down for good in the 1970s, but this glorious ad in Herald Square refuses to let New York forget the men’s hats, suits, and overcoats they were known for through the 20th century.

February 27, 2022

A lost East Village alley on a 1963 downtown map

Old maps tell us a lot about the subtle changes to New York’s streetscape. Take this illustrated map of the Village that’s almost 60 years old, for example.

Published in August 1963 by the Village Voice, the map covers not just Greenwich Village but a portion of the Meatpacking District (see “Little West 12th Street” in very small print), a slice of Chelsea, and a bit Gramercy Park, with that sliver of Irving Place at the top right.

The map extends all the way east to First Avenue. Makes sense; the newly christened East Village was at the time becoming a hipster alternative to pricey Greenwich Village, with its own clubs, bars, theaters, and head shops. The new, young residents here would likely be Village Voice readers.

“Stuyvesant Alley,” by Armin Landeck, 1940

“Stuyvesant Alley,” by Armin Landeck, 1940Much of the Village Voice map aligns with the streetscape today. But there’s something missing in the contemporary East Village—it’s a place name on the map between Third and Second Avenues and East 11th and 12th Streets.

“Stuyvesant Alley,” the map says, marking a slender lane in the middle of the block. Okay, but there’s no Stuyvesant Alley anymore. So what happened to it?

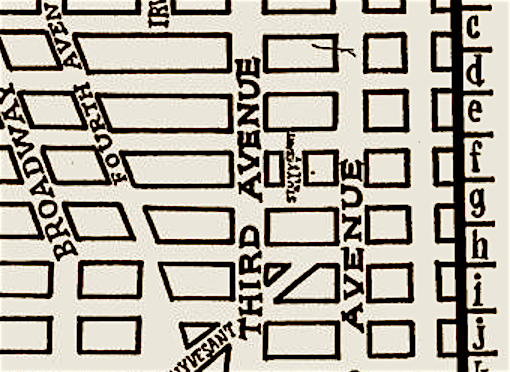

Stuyvesant Alley, not named on this 1868 map

Stuyvesant Alley, not named on this 1868 mapFirst, let’s see what the backstory is. The “Stuyvesant” name is obvious; the alley was created on land once part of the farm Peter Stuyvesant established for himself and his descendants in the 17th century. Parcels of his “bouwerie” were sold off for development in later centuries, but the Stuyvesant name stuck.

Stuyvesant Alley appears in several 19th century neighborhood maps, like the one above, from 1868. The alley isn’t named, but it runs through East 11th to East 12th Street. It also seems to have some small buildings lining it—perhaps stables?

By 1879, the alley’s name made it on the map (above), along with other places in the heavily developed neighborhood, like the Astor Place Hotel and Tivoli Theatre.

In the 1920s, Stuyvesant Alley showed up in an article in the New York Herald. An art exhibit was to be held at One Stuyvesant Alley in November 1922, the paper reported, hosted by a group of painters who called themselves the Co-Arts Club.

“The Co-Arts Club has established themselves in Stuyvesant Alley, the last frontier of Bohemianism on the East Side,” the Herald stated wistfully. “The ruthless march of tenements and factories has left only the alley untouched and the light bathes the studios there with an undimmed purposefulness.”

The painting of the alley as a narrow driveway surrounded by red brick and stone buildings (second image above) is the work of Armin Landeck in 1940. Whether Landeck’s depiction was true to life is hard to know; it’s also unclear which end of the alley he’s looking down.

His view is different from that of this 1934 photo of Third Avenue and East 11th Street (above), which shows the buildings on either side of the entrance to Stuyvesant Alley.

The alley made it into the 1960s, since it’s on the Village Voice map. But the trail goes cold after that.

To explain its undocumented disappearance, I’m going with what the Village Preservation’s Off the Grid blog concluded in 2014, when they took a closer look at Stuyvesant Alley: “The alley appears to have been wiped from the map in the 1980s when NYU built their large dorm on the corner of Third Avenue and East 11th Street.”

Thanks to Mick Dementiuk for sending the link to the map my way.

[Top image: Village Voice map via The Copa Room; second image: Brooklyn Museum; third image: fourth, fifth, and sixth images: NYPL]

February 21, 2022

Ephemeral New York explores the servants of the Gilded Age in a new podcast

Gilded Age new rich and old money families had one thing in common: they all employed an army of servants to clean their mansions, mind their children, prepare their meals, drive their carriages, and take care of any other task members of elite society deemed necessary. But who were these butlers, chambermaids, laundresses, cooks, valets, and coachmen—and what was life like for them?

In a new episode of the history podcast The Gilded Gentleman, host Carl Raymond (writer, editor, and social and cultural historian) has invited me to take a look at the roles and responsibilities of domestic staff in grand mansions and more modest homes. We’ll explore what servants did—and who they really were. The episode pays tribute to the “invisible magicians” without whom the dinners, balls, and daily workings of households of the Gilded Age would never have been possible.

The episode debuts on Tuesday, February 22. You can download it and subscribe to The Gilded Gentleman on Apple or your favorite podcast player. The Gilded Gentleman podcast is produced by The Bowery Boys.

[Photo: MCNY 1900, MNY204627]

What went on at the Gilded Age ‘Patriarchs balls’ for New York society

If the 19th century Gilded Age was still with us, New York society would right now be bracing for the end of the annual winter social season.

Evenings in the boxes at the Academy of Music, French dinners at Delmonico’s, costume balls at Knickerbocker mansions—each week between November and the arrival of Lent offered an intoxicating mix of social events for Gotham’s old-money “uppertens” (aka, the richest 10,000 people in the city).

But there was one type of ball that owes its existence to the clubby exclusiveness fostered during this late 19th century era of consumption and corruption: the Patriarchs Balls.

A ticket to a Patriarchs Ball in 1892

A ticket to a Patriarchs Ball in 1892Patriarchs Balls grew out of a group called the Society of the Patriarchs, formed in 1872 by Ward McAllister (below)—the Southern-born social arbiter who became Caroline Astor’s sidekick and gatekeeper as she put her imprint on Gilded Age society.

The Patriarch Balls, given several times in a social season at Delmonico’s, had a specific purpose. “Both Astor and McAllister lamented the ‘fragmentation’ of society and hoped to alleviate it by creating a circle of elite New Yorkers at the top of the city’s social hierarchy,” wrote Sven Beckert in his 2003 book, The Monied Metropolis.

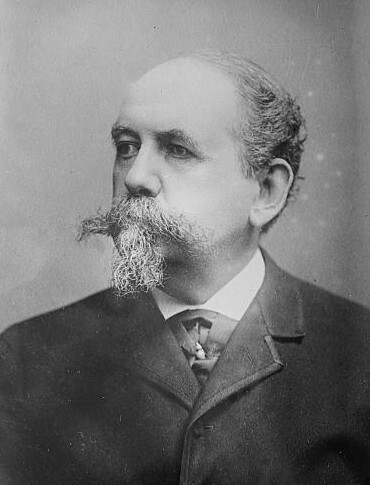

Ward McAllister

Ward McAllister“For that purpose they appointed 25 ‘patriarchs’—among them Eugene E. Livingston, Royal Phelps, and William C. Schermerhorn—who each could invite five women and four men to the balls and dinners organized by Caroline Astor.”

Those guests who “passed the scrutiny of the Patriarchs gained admission to the Four Hundred, a figure equal to the number of guests who could fit comfortably into [Caroline Astor’s] ballroom, where an annual ball was held on the third Monday in January,” stated William Grimes, author of Appetite City.

Delmonico’s menu for an 1897 Patriarchs Ball

Delmonico’s menu for an 1897 Patriarchs BallWhat actually happened at a Patriarchs Ball? Based on the breathless coverage in the many New York newspapers of the Gilded Age, the events sound a lot like any other ball.

“At 11:30 the guests began to arrive, and dancing was begun at once,” wrote the New York Times on February 14, 1888—the last Patriarchs Ball of the social season. “Round dances only were in order in the large ballroom.” Two orchestras provided the music, and the hall and stairway were decorated with vines and palms. Roses, lilies, and tulips filled Delmonico’s dining rooms.

Coverage of a Patriarchs Ball, 1881 New York Times

Coverage of a Patriarchs Ball, 1881 New York Times“At 12:30 supper was served, and was unusually elaborate,” the Times reported. “Terrapin and truffled capons were among the delicacies.”

Patriarchs Balls continued into the 1890s. But as the division between old money and new rich dissolved and a brutal recession hit the city in 1893, the appetite regular New Yorkers had for this kind of frivolity began to wane.

Patriarchs Ball ticket, 1896

Patriarchs Ball ticket, 1896The New York Times covered their last Patriarchs Ball in 1896. In 1897, they simply reported in a small article that one Patriarch, a banker named James Kernochan, was run over on his way to a ball that year “by either a vehicle or a car somewhere on 42nd Street.” (Mr. Kernochan, of 824 Fifth Avenue, was left unconscious.)

McAllister’s fall from grace also contributed to the demise of the Patriarchs. After he published something of a tell-all in 1890, and then spoke to the press about exactly who, supposedly, was part of The Four Hundred, Mrs. Astor and her circle shunned him.

[Top image: Alamy; second image: MCNY 83.20.2; third image: LOC; fourth image: NYPL Menu Collection; fifth image: New York Times headline 1881; sixth image: MCNY 40.108.134]