Esther Crain's Blog, page 56

December 26, 2021

What happened to New York City’s 14th Avenue?

You know 12th Avenue in Manhattan, the Far West Side avenue that becomes the West Side Highway. And you may have heard of 13th Avenue, a short-lived thoroughfare built on landfill in the 1830s from 11th Street to about 25th Street that had a dreary, creepy vibe—based on photos and newspaper accounts.

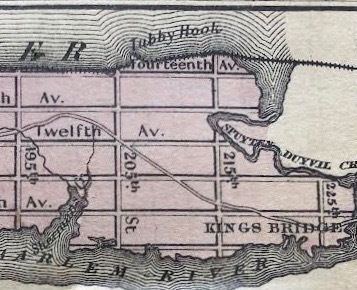

But 14th Avenue in Manhattan? I’d never heard of it until I saw the 1860 Johnson’s Map of New York (above). In the uppermost part of Manhattan, at Tubby Hook and the railroad tracks that hug the Hudson River, there’s a small stretch marked “Fourteenth Avenue.”

Even stranger, 13th Avenue makes an appearance as well, running from about 168th Street to Spuyten Duyvil.

The Commissioners’ Plan of 1811, the map that laid out Manhattan’s street grid, says nothing about 14th Avenue. The last street on that map is 155th Street, and to the north are scattered place names (like Fort George and Kings Bridge) as well as the names of landowners.

There are a few mentions of 14th Avenue in newspaper archives, specifically when it comes to real estate transactions. In 1875, the New York Times noted that a plot from 214th to 215th Streets along 14th Avenue exchanged hands for $80,000.

Some other 19th century maps mark 14th Avenue, like the one above from 1879.

So why did 14th Avenue (and this slice of 13th Avenue) get de-mapped? Did the city decide it was too small to be an avenue, too insignificant at only 10 or so blocks long? Meanwhile, Tubby Hook is still on the map; even Google notes this spit of land jutting into the Hudson (below).

It likely has to do with Inwood Hill Park. Where 14th Avenue is marked on the 1860 map happens to be where Inwood Hill Park Calisthenics Park is today, right alongside the water. I don’t know when the Calisthenics Park opened, but Inwood Hill itself became an official city park in 1926.

A short avenue had no place inside Inwood Hill Park. As a result, 14th Avenue forever bit the dust.

[Third image: NYPL; fourth image: Google Maps]

December 20, 2021

A piece of the cut-rate Lower East Side remains on Orchard Street

Hidden behind scaffolding and weathered by the elements, the sign is not easy to see. But when you do make it out, you’ll feel like a time machine has delivered you back to the 1920s Lower East Side—when Orchard Street meant cut-rate shopping, not pricy cocktails.

“Ben Freedman Gent’s Furnishings” (such an old-timey way to describe clothes and hats!) got its start on Orchard Street in 1927, when Mayor Jimmy Walker was partying at Manhattan speakeasies and the Woolworth Building qualified as the city’s tallest skyscraper.

The sign may be faded, but the business is still going. Sounding feisty, Freedman was quoted in a 1977 Daily News story about the poor prospects of Orchard Street. “Oh it’s changed for sure, so what?” he told a reporter, who added that Ben had been at his store peddling bargains for 50 years. “It’s still a great street.”

The Lo-Down has more on Ben’s business.

December 19, 2021

A stunning Christmas feast served to guests at a posh Gilded Age hotel

I’m not sure what’s going on with the Hotel Wolcott these days. Prior to 2020, this pink brick and limestone landmark on 31st Street off Fifth Avenue catered to tourists looking for an inexpensive place to bed down in Manhattan. After Covid hit, the Wolcott stopped accepting “transient hotel guests.”

The Wolcott at 31st Street and Fifth Avenue, about 1910

The Wolcott at 31st Street and Fifth Avenue, about 1910In the Wolcott’s Gilded Age heyday, however, the hotel’s clientele were a lot higher on the social ladder. Opened in 1904 in the hopping theater and shopping district near Herald Square that was fast supplanting the rough and ready Tenderloin, this Beaux-Arts beauty hosted notables like Edith Wharton and Isadora Duncan.

The Wolcott menu front cover

The Wolcott menu front coverThe Wolcott operated on what was known as the “European plan,” which meant that meals were not included in the room price. So when the hotel dining room put together this mind-blowing Christmas dinner menu for December 25, 1905, hotel guests had to pay extra.

What a feast it was! The menu featured more than a hundred options, starting with an array of oysters and clams and then 25 or so relishes (lots of caviar and “chow-chow”), soups (turtle, of course; it’s an old New York favorite), and fish (codfish tongues?) before getting to the official entrees.

If beef, ham, or chicken isn’t your idea of a Christmas dinner main course, the Wolcott offered plenty of game options, like grouse, woodcock, and partridge.

A chef in the Wolcott kitchen, 1917

A chef in the Wolcott kitchen, 1917The vegetable choices were quite extensive, and that list included different varieties of potatoes, including “French fried”—perhaps an early mention of the classic side we’re so used to with a burger today.

The dessert course went old-school with plum pudding. But look at all those ice cream options! Fruit, cheese, and then coffee and tea rounded out the feast. I wonder what “Wolcott special milk” is?

The menu reveals some things about life among the upper classes in Gilded Age New York. Unlike today’s pared-down, curated restaurant menu, variety seems to have been important. French dishes were certainly popular, likely thanks to the influence of Delmonico’s, which by 1905 had moved up to 44th Street and was still a leading option in a city where dining out was becoming more of a regular thing.

How the hotel’s dining staff managed to obtain and store all of these food choices is mind-boggling. Chefs must have been down at the city’s great food markets, like Washington Market, early in the morning, and an army of cooks likely chopping, peeling, and cleaning all day.

One thing remains the same, though: Christmas dinner was meant to be a celebration, just as it is today.

[Top image: MCNY, x2011.34.303; Second image: NYPL

This oldest photo of the moon was taken in 1840 on a Greenwich Village roof

The black and white image has deteriorated over the last 180 or so years, and it evokes something ghostly and supernatural. But this crescent shape amid light and shadow is considered the oldest surviving photo of the moon—taken in 1840 by an NYU professor who pioneered early photography.

The backstory of the photo begins in 1839. That’s when word reached New York City about the new photography process developed in France by Louis Daguerre.

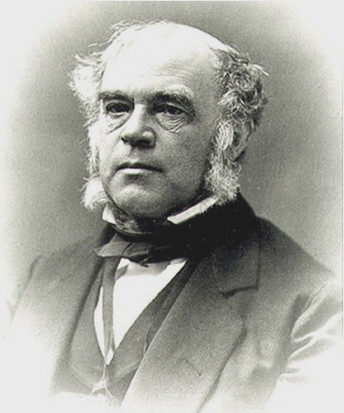

John William Draper took a keen interest. Draper, 29, was a London-born chemistry and natural history professor and part of the faculty at the new college on Washington Square then known as the University of the City of New-York (now called NYU).

Draper too had experimented with capturing light, and he “quickly realized the importance of the invention of the daguerreotype, becoming one of the first Americans to try the process,” stated Off the Grid, the blog for the historic site Village Preservation.

The NYU building, since demolished, where the moon image was taken

The NYU building, since demolished, where the moon image was takenDraper, as well as his NYU colleague Samuel Morse (a professor of painting before he invented the telegraph), began making daguerreotypes, according to Arthur Greenberg’s book, From Alchemy to Chemistry in Picture and Story, experimenting in the studio observatory on top of the university’s main building (above).

Draper’s first successful daguerreotype that survives is a copy of an image of his 33-year-old sister, Dorothy Catherine Draper, below. But set his sights on something more extraordinary: a daguerreotype showing the surface of the moon.

Dorothy Catherine Draper, at about age 33

Dorothy Catherine Draper, at about age 33Though he may not have been the first person to capture an image of the moon, Draper’s moon shot, so to speak, is the oldest that survives (top image).

The photo at top was likely the specific one Draper perfected on March 26, 1840. “The extensively-degraded plate shows part of a vertically ‘flipped’ last-quarter Moon—so lunar south is near the top—which would indicate his use of a device called a heliostat to keep light from the Moon focused on the plate during a long 20-minute exposure,” according to the site Lights in the Dark by Jason Major.

John William Draper, decades after his first moon photos

John William Draper, decades after his first moon photosThroughout his life, Draper racked up numerous achievements as a scientist, writer, philosopher, and physician, even cofounding NYU’s medical school. His moon image, however, didn’t get the recognition it deserved.

“Despite his accomplishment, Draper’s efforts received only modest recognition from his contemporaries; until recently his lunar daguerreotypes were believed to be lost,” according to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which has one of his moon daguerreotypes in its collection.

Like so many other notable 19th century New Yorkers, both Draper and his sister are buried in Green-Wood Cemetery.

December 13, 2021

The 19th century remains of a fabled Grand Street department store

Standing across the street at Grand and Orchard, you just know this unusual building with the black cornice and curvy corner windows has a backstory. Though it’s a little rundown and has a strange pink paint job, this was once the home of a mighty 19th century department store known as Ridley’s.

Ridley’s story begins in the mid-1800s. Decades before Ladies Mile became Gilded Age New York’s premier shopping district, browsing and buying fashionable goods meant going to Grand Street, which was lined with fine shops and dry goods emporiums east of Broadway in the antebellum city.

The best known of these dry goods emporiums and a rival to neighbor Lord & Taylor (located on Broadway and Grand) was Ridley’s.

Founded by English-born Edward A. Ridley as a small millenary store at 311 Grand Street in 1848, according to a Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) report, Ridley’s expanded by buying many of the former residential buildings on the block. Ridley then built a new mansard-roof structure at the corner of Grand and Allen Streets accessible to street car lines and the ferry to Grand Street in Brooklyn.

In the 1880s, Grand Street was still a shopping district but no longer elite. Lord & Taylor had already relocated uptown to a prime Ladies Mile site at Broadway and 20th Street. But Ridley’s sons, who had taken over the business, commissioned a new building at the corner of Grand and Orchard Streets.

Five stories tall with a cast-iron facade, the new Ridley’s opened in 1886. The space featured a “curved, three-bay pavilion that may have been originally crowned by a squat dome, or a flagpole,” the LPC report stated.

Inside, 52 “branches of trade” sold everything from clothes to furniture to toys and employed approximately 2,500 people. Stables behind the store “provided parking for horses and carriages,” according to The Curious Shoppers Guide to New York City, by Pamela Keach.

The amazing thing is, the new block-long Ridley’s would only occupy the space for 15 years. In 1901, Ridley’s went out of business, according to an Evening World article that year—partly a victim of its increasingly unappealing location on the crowded Lower East Side.

After Ridley’s departed, the space was chopped up into smaller retail outlets. Above is the building in 1939-1941 with a housewares store on the ground floor. Today, a men’s clothing store exists there.

[Second image: LPC; third image: MCNY 261260; fourth image: NYC Department of Records and Information Services]

December 12, 2021

The forgotten Gilded Age model who posed for Central Park’s most famous statue

If you’ve ever passed the Sherman monument at the Fifth Avenue and 59th Street entrance to Central Park, then you’ve seen her likeness before—she’s the Greek goddess Victory, with wings and sandals, leading General Sherman astride his horse to Civil War triumph.

But who was the real-life woman who lent her image to this Augustus Saint-Gaudens sculpture, which has stood at Grand Army Plaza since 1903?

Researchers, including her own descendants, have pieced together some of her story as a sought-after model in Gilded Age New York, and it holds some surprises.

With Augustus Saint-Gaudens, the sculptor of the Sherman monument, in an 1897 sketch by Anders Zorn

With Augustus Saint-Gaudens, the sculptor of the Sherman monument, in an 1897 sketch by Anders ZornShe was born Harriette Eugenia Dickerson in Columbia, South Carolina, in 1873. “Research, including findings by her cousin Amir Bey, shows that before the Civil War the government designated Anderson’s family ‘free colored persons’; they owned land and earned wages,” stated the New York Times in August 2021.

“But the brutal enforcement of Jim Crow laws in the South and financial hardship eventually drove Anderson and many of her relatives northward,” the Times continued.

She and her mother moved to New York, probably the 1890s. They settled into a “sepia-colored brick building on Amsterdam Avenue at Ninety-Fourth Street,” wrote Eve M. Kahn in an October 2021 article for The Magazine Antiques. (Below, Amsterdam Avenue at 93rd Street in 1910)

Amsterdam Avenue at 93rd Street in 1910, a block from where Anderson lived in the 1890s

Amsterdam Avenue at 93rd Street in 1910, a block from where Anderson lived in the 1890sGoing by the name Hettie Anderson, she began working as a seamstress “and occasionally as a store clerk, while modeling and likely studying at the then-new Art Students’ League on West Fifty-Seventh Street,” stated Kahn.

Anderson was soon in demand as an artist’s model, and she was lauded for her looks. “The recognized ‘Trilby’ of Gotham is Miss H.E. Anderson,” wrote the New York Commercial in 1896, referring to the artist model in the George du Maurier novel. “She is a charming young woman, whose beauty of form and face make her in constant demand among artists.”

Those artists included Saint-Gaudens, Daniel Chester French, and John La Farge. “Miss Anderson’s coloring is quite as exquisite as her shapeliness,” the Commercial stated. “She is richly brunette in type, with creamy skin, crisp curling hair, and warm brown eyes.”

Whether the artists who she posed for knew she was African American is unclear. “New York census takers listed her as ‘white,’ wrote Kahn. “But she definitely did not ‘pass’ or ‘cross the line’—that is, she did not hide her ethnicity by cutting off family members.”

After the turn of the century, she continued modeling, and Saint-Gaudens used her likeness on $20 coins and also gave her the portrait bust he used when working on the Sherman monument.

“Anderson’s likeness can be seen in French’s sculptures at Congress Park in Saratoga Springs, N.Y.; in cemeteries in northern New Jersey and Concord, Mass.; and in entryways to the St. Louis Art Museum and Boston Public Library,” wrote the Times.

She might also be the model for Adolph Alexander Weinman’s “Civic Fame,” on top of the Manhattan Municipal Building (above)—though Audrey Munson, another top model of the era, is often credited for that 1914 sculpture.

In the 1910s, modeling jobs became harder to come by. French and sculptor Evelyn Beatrice Longman helped her find work as a classroom attendant at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, wrote Kahn, and by the 1920s, her health was failing.

Daniel Chester French’s “Spirit of Life,” in Saratoga Springs, based on Anderson

Daniel Chester French’s “Spirit of Life,” in Saratoga Springs, based on AndersonAccording to [her brother] Charles’s granddaughters, she suffered a breakdown after seeing a lover killed in traffic on Amsterdam Avenue,” stated Kahn. “Every evening, she would inexplicably open and shut a window, shouting the name of a cousin, Sarah ‘Sallie’ Wallace Arnett, a church leader who likely disapproved of modeling careers.”

More personal troubles may have contributed to the breakdown. A 1913 article in the New York Age reported that Anderson filed suit against her husband, James Anderson, a Harlem newspaper publisher, alleging adultery. They had been married since 1892, according to the article, and had no children.

Like many models then and now, her name was mostly forgotten as the decades went on. She died in 1938, and “her death certificate listed ‘model’ as her profession,” wrote Kahn, adding that she and her mother are buried in her hometown of Columbia.

For any readers interested in learning more about Hettie Anderson, Landmark West! is hosting a Zoom event featuring author and scholar Eve Kahn. The event is on December 15 from 6-7 p.m., and Ephemeral readers can get a complementary ticket by contacting ephemeralnewyork @ gmail or via DM.

[Second image: Wikipedia; third image: NYPL Digital Collection; fourth, fifth, and sixth images: Wikipedia]

During the Civil War, Brooklyn held a spectacular ice skating carnival

Ice skating had always been a winter pastime in New York, when the many ponds that once existed in Manhattan routinely froze over. But when the lake at the new Central Park opened to skaters in 1858, the ice skating craze of the 19th century city officially began.

“Carnival of the Washington Skating Club, Brooklyn”

“Carnival of the Washington Skating Club, Brooklyn”Central Park may have been the top spot for gliding across ice and showing off your skating attire—and maybe finding romance, too. Ice skating was perhaps the only activity men and women could partake in together without breaking social customs or having a chaperone in tow.

But Brooklyn wasn’t about to let Manhattan have all the fun. On a Sunday afternoon in February 1862, the recently formed Washington Skating Club held a magnificent skating carnival at Brooklyn’s Washington Pond, on Fifth Avenue and Third Street in today’s Park Slope.

“Skating Carnival in Brooklyn, February 10, 1862,”

Harper’s Weekly

“Skating Carnival in Brooklyn, February 10, 1862,”

Harper’s Weekly

Brooklyn in 1862 was a separate city, of course—a newly formed booming metropolis of about 266,000 (compared to Manhattan’s 805,000) that threw its support behind the Union and sent many soldiers to Civil War battlefields.

But the war didn’t preclude spending a afternoon and evening frolicking on the ice in princess, wizard, and other costumes, with a 25-piece band playing nearby and fireworks lighting up the winter sky.

Six thousand Brooklyn residents attended the skating carnival, which began at 3 p.m. “Reflector lamps” on poles helped illuminate the ice, and moonlight gave the carnival an ethereal glow.

“The bright sky, the exhilarating atmosphere, and the excellent condition of the ice proved temptations too strong for even discontent to resist, and by sundown the up-cars were thronged with eager crowds of both sexes and nearly all ages, from the toddling ‘3 year old’ to venerable age,” wrote the Brooklyn Evening Star.

The only thing spoiling the carnival? Pickpockets. Police arrested four men who were “mixed up among the skaters, endeavoring to ply their vocation,” stated the Brooklyn Times Union on February 12.

Washington Park wasn’t just the site of a skating carnival. Here, the short-lived sport of ice baseball was played in the winter (above, in the 1880s)…while fans shivered.

[Top illustration: MCNY MNY122495; Second illustration: Sonofthesouth.net; third illustration: Fine Arts America]

December 6, 2021

An Impressionist painter’s Christmas in Madison Square Park

Paul Cornoyer’s work has been featured in Ephemeral New York many times before; this Impressionist artist originally from St. Louis was captivated by the Gilded Age city’s energy and vitality, as well as the beauty of its parks.

Cornoyer depicted Madison Square Park many times. But to my knowledge, “Christmas in Madison Square Park” is the only painting of his that captures what appears to be New York City’s first official park Christmas tree.

The tree—a 60-footer from the Adirondacks—made its debut in Madison Square on December 21, 1912, lit with 1,200 colored lights donated by the Edison company. It was such a hit, decorated Christmas trees soon became the norm in many city parks and squares.

I haven’t been able to confirm the date of the painting. Cornoyer moved to New York City in 1899 and spent several years here, so if the tree in this nocturne isn’t the very first park Christmas tree, it’s likely to be one of the firsts.

What a beauty it is, next to the church spire in the blue glow of a winter’s night!

Shy lonely brownstones hiding in the cityscape

New York is a city where buildings proudly announce themselves—with bright, windowed lobbies, or large logos, or architectural bells and whistles that convey something grand or self-important about the space.

16 East 58th Street

16 East 58th StreetThen there are the lone, faded brownstones and row houses that tend to go unnoticed.

Once flanked by identical houses on pretty, exclusive streets in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, these solo dowagers are usually stepped back from the sidewalk and wedged between commercial buildings, their facades altered in the contemporary city.

58 East 56th Street

58 East 56th StreetHouses like these, sometimes found in a pair (above), can be seen in pockets all over Gotham.

Number 58, still part of a pretty row in 1939-1941

Number 58, still part of a pretty row in 1939-1941But quite a few seem to be in Midtown closer to the East Side, the remnants of a rush of Gilded Age residential development centered near Central Park when every Shoddyite (aka, nouveau riche New Yorker) wanted their own brownstone.

127 and 129 East 60th Street

127 and 129 East 60th StreetBut New York has what Walt Whitman called the city’s “tear-it-down-and-build-it-up-again spirit.” Commercial development crept northward. Within a generation or two—or at least by midcentury—many of these residential blocks met the wrecking ball, replaced by loft buildings or office towers dedicated to business.

Same buildings, altered in 1939-1941

Same buildings, altered in 1939-1941And the remaining brownstones? Abandoned as single-family homes and carved up into apartments with ground-floor store space, they faded quietly into the background, often hidden behind a store sign or years of construction scaffolding.

Lexington Ave and 58th Street

Lexington Ave and 58th StreetThey’re holdout buildings of sorts, but perhaps more by accident than the result of a stubborn owner. Once you notice one, it’s hard not to wonder about its former life as an elegant or expensive residence: who lived there, what was the neighborhood like before it became a commercial corridor?

I’ve found a few earlier photos to give an idea of what they looked like around 1940, when they were still part of a residential block but with commercialism creeping up. Consider these remaining brownstones the phantoms of an earlier layer of city history.

[Third photo: NYC Department of Records and Information Services; Fifth photo: NYC Department of Records and Information Services]

December 5, 2021

The soaring, stunning vaulted ceilings of an East Side Trader Joe’s

Most shoppers flock to Trader Joe’s because of the low prices and extensive food options—and a checkout line that seems a little speedier than at other city supermarkets.

But the new Trader Joe’s that recently opened in the cavernous space under the Queensboro Bridge at 59th Street and First Avenue offers a reason to look not at the shelves but high up at the 40-foot ceiling.

The cathedral-like ceiling features a seemingly endless cascade of domed vaults and columns covered in off-white tiles arranged like a basket weave.

The tiling was the work of Rafael Guastavino, a Spanish immigrant who patented a tiling system “based on the building methods behind Catalan vaulting” in the early 20th century, according to Architect Magazine. Grand Central Station’s Whispering Gallery, the Manhattan Municipal Building, and other architectural landmarks of New York’s progressive era also feature Guastavino tiles.

The original vendors’ market, 1915

The original vendors’ market, 1915Bridgemarket, as the space under the bridge is known, might seem like a strange place to open a retail food outlet. But its roots as a marketplace run deep.

Inside the marketplace, 1915

Inside the marketplace, 1915Five years after the Queensboro Bridge was completed in 1909, this space was used as an open-air market (above, in 1915), where vendors came in wagons to sell produce and set up booths.

That original market closed in the 1930s. But it wasn’t until 1999 when Food Emporium renovated the space to fit a modern supermarket; the store featured a mezzanine level that made the view of the ceiling tiles almost magical (below).

Flashback 2014, when Food Emporium operated the space

Flashback 2014, when Food Emporium operated the spaceFood Emporium left Bridgemarket in 2015—and now Trader Joe’s is giving a try to this soaring, stunning monument to New York’s food market history.

[Photo 3: MCNY x2010.11.5557; Photo 4: MCNY x2010.11.10030]