Esther Crain's Blog, page 55

January 23, 2022

An Irish servant girl’s passionate reply to her Gilded Age wealthy employers

Think about the army of servants a wealthy New York City household would typically have in the Gilded Age. Cooks, coachmen, valets, butlers, grooms, laundresses, and others cleaned parlors and bedrooms, prepared meals, drove the carriage, laid out clothes, polished the silverware, watched the children, and took care of almost every household need.

Servants taking out ads for employment at the New York Herald office, 1874

Servants taking out ads for employment at the New York Herald office, 1874Sure it made life for the rich family easier, and it offered a relatively decent source of income to poor newcomers. (Room, board, and a half-day Sunday helped sweeten the deal.) Also, employing numerous servants was a status symbol in an era when appearances of wealth meant everything.

Yet along with a house full of servants came servant problems. In the Gilded Age, these problems coalesced under one hotly debated topic: “The Servant Question.”

Trade card for the Lustro company on Duane Street during the Gilded Age

Trade card for the Lustro company on Duane Street during the Gilded Age The Servant Question—sometimes called “The Servant Girl Question”—was the subject of endless newspaper and magazine articles in the late 19th century.

The question was really a mix of questions of concern to well-off women, who were typically tasked with managing their family’s servant staff: Why is it so hard to find competent servants? Should you be kind or strict? Is the servant the problem—or is it the mistress of the house to blame because of her poor management skills?

On January 20, 1895, the New York Times launched an article series, “Competent Domestics,” exploring the issue. Twelve society women—including Mrs. Russell Sage (wife of the financier) and Mrs. Charles Parkhurst (wife of the of the Madison Avenue Presbyterian Church) weighed in.

“I never allow my servants an afternoon off during the week,” said Mrs. Walter Lester Carr, wife of a prominent doctor. “Why should I lose so much time and put myself to a great deal of inconvenience in doing the work myself?”

Mrs. Robert McArthur, wife of the pastor of Calvary Baptist Church on 57th Street, put the blame elsewhere. “I think if people would treat servants less like animals or a part of their household furniture they would get along better with them. I know people who say, ‘keep servants down as much as you can, and you will get more out of them.'”

The one thing glaringly missing from the article was the voice of an actual servant. Soon one sent in a letter to the editor, which the Times printed on February 17.

“What an Irish Girl Thinks” was the headline. Written without details about where she worked or who she worked for, this Irish servant—one of thousands of Irish girls and women (often derided as “Bridgets”) who served in a domestic capacity because other positions tended to be shut off to them in the 19th century—gave a passionate reply.

“So much has been said lately through your paper on the servant question that I venture to ask you to be kind enough to listen to a servant’s view of the case,” the girl wrote. “That our faults have been told and retold is certainly a fact. Some of those faults I am willing to admit; others I deny.”

The servant girl stated that there are good and bad mistresses: “good, kind, conscientious mistresses, whom every word and action command respect from their servants and who never have and never will have any trouble in getting good servants.”

“But there is another class who look upon their servants as a lot of inferior beings, put into this world for the sole purpose of drudging for them from morning till night, and who are afraid that if they treat their servants with anything like respect it will lower them one step on the social ladder, which they found so very difficult to climb.”

“If such people would only remember that we are human beings, flesh and blood, just as they are, but lacking all their advantages, educations, etc., which go a great way to help people overcome their faults, they would have better servants.”

“Tradesmen, laborers, in fact everybody who work for a living, look forward to the end of their day’s work; but the New York servant—’No.’ She can sit inside her prison bars (basement gates), and dare not go out and get a breath of God’s fresh air, which might help her temper, and benefit her mistress for the next day’s work. I call that a mild form of slavery and those people came into this world a century too late.”

The end of the Irish girl’s letter offers a hint of modesty—and an acknowledgement of her lowly status in the Gilded Age city.

Servants at the New York Herald office looking for “situations”

Servants at the New York Herald office looking for “situations”“I will apologize for the length of my letter, and hope you will give it a place in your valuable journal. But for all the errors, grammatical or otherwise, which it contains, the fact that I’m a servant, and nothing better of my class is expected is the only apology I will offer.”

We know what happened to the servant question: it resolved itself as the practice of employing 8, 10, 15 or more servants per household ended. After the turn of the century, rich New Yorkers began moving into luxury apartments and didn’t need an enormous staff to manage. Immigration quotas also likely played a role in reducing household staff, since the ready supply of cheap labor was scaled back.

Servants at the Salvation Army Home on Gramercy Park, undated

Servants at the Salvation Army Home on Gramercy Park, undatedBut what happened to this Irish servant who wrote the letter? Like so many other Irish immigrant girls and women in the city at the time, perhaps she lived out her life as a chambermaid, laundress, or cook—socializing at a nearby parish, sending money to family back home, and hopefully finding a family that appreciated her.

[Top image: LOC; second image: MCNY, MN137316; third image: MCNY 1900, MNY204627; fourth, fifth, sixth, and seventh images: NYT; eighth image: Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper via Clarkart.edu; ninth image: New-York Historical Society, undated]

January 17, 2022

The men on the riverfront overshadowed by the modern city

Martin Lewis made this etching, “From the River Front,” in 1916. What a turning point in New York City history: skyscrapers have started going up in Lower Manhattan, changing the scale and feel of the streets beside the East River.

But on Belgian-block South Street, the low-rise buildings don’t overshadow the men working and congregating there. This horse-powered part of Manhattan is doing business as it always has. Meanwhile, the 20th century looms.

Here’s more of Martin Lewis’ enchanting and haunting etchings of New York’s pockets and corners.

[Source: Invaluable]

5 Remnants of the 19th century West Side village of Manhattanville

Think of Manhattan in the early 1800s as an urban center at the tip of the island surrounded by a collection of small countryside villages.

The city itself, with a population under 100,000, was concentrated below Canal Street. But a few miles up the Hudson River was sparsely populated Greenwich Village. Parts of today’s Upper West Side once formed the farming village of Bloomingdale. Harlem started off as a rural area in the 17th century as well.

Then there’s Manhattanville (below, at the top of the map). Founded in 1806 in a valley known as Harlem Cove, this former outpost 10 miles from the city was centered on today’s 125th Street and Broadway.

It’s not an accident that Manhattanville was founded here. In the early 19th century, this was the crossroads of Bloomingdale Road and Manhattan Street—two crucial arteries that connected residents to Harlem and the lower city. (Manhattan Street likely gave the village its name.)

“Building lots were being advertised for sale ‘principally to tradesmen’ in this enclave that already boasted a ‘handsome wharf,’ ‘convenient academy,’ and an ‘excellent school,'” according to a Historic Landmarks Commission (HLC) report.

The village’s early population included mostly poor residents of British and Dutch descent, plus a small number of African Americans, per the HLC report. Decades later, Manhattanville would be better known as an industrial center and also an early transit hub.

“By the mid-1800s, this picturesque locale was the convergence of river, rail, and stage lines,” wrote Eric K. Washington in his book, Manhattanville: Old Heart of West Harlem. The first northbound passenger stop on the Hudson River Railroad was at Manhattanville, Washington wrote. (Below, the little white Manhattanville train depot, in front of an early building for Manhattanville College.)

Manhattanville remains on the map and as a neighborhood name. But like other villages, it became part of the larger city in the early 20th century.

Still, bits and pieces of the old village exist. For starters, the streets are a little askew; they don’t always align with the official street grid laid out in 1811. Before crossing Amsterdam Avenue, 125th and 126th Streets (the former Lawrence Street) make hard turns and slant northwest toward the Hudson.

This charming nonconformity makes it possible to stand at the corner of 126th and 127th Streets or find yourself at the intersection of 125th and 129th Streets. It’s a little puzzling, but it reminds you of the life and activity in New York that predates the Commissioners‘ Plan.

What else still exists of the former village? Probably the loveliest remnant is the yellow clapboard parish house for St. Mary’s Episcopal Church. An outgrowth of St. Michael’s church in Bloomingdale, St. Mary’s was founded in 1823 for Manhattanville residents. (St. Mary’s was the first church in the city to do away with pew rentals, which was a common practice at the time.)

The original church was a simple white wood structure consecrated in 1826, replaced in 1908 by the current English Gothic-style church building. The yellow parish house, however, was built in 1851 and feels more country village than urban city.

St. Mary’s Church is the site of a more eerie piece of Old Manhattanville: a burial vault under the church porch containing the remains of one of the village’s founders, a man named Jacob Schieffelin (along with the remains of his wife and brother). Schieffelin donated the land on which St. Mary’s was built.

Schieffelin, a Loyalist during the Revolutionary War, amassed his post-independence fortune as a wholesale druggist and mercantile owner. He was one of a handful of prominent New Yorkers who made up the founding families of Manhattanville.

Among them were the widow and sons of Alexander Hamilton, as well as Daniel F. Tiemann—who served as mayor of the city from 1858 to 1860 and owned D.F. Tiemann & Company Paint & Color Works, which moved to the village in 1832. The arrival of the paint factory helped turn Manhattanville into an industrial center powered by an influx of German and Irish immigrants in the mid-19th century.

On the same block of 126th Street is another hint of old Manhattanville: the Sheltering Arms Playground and Pool. The name comes from the Sheltering Arms, which took in children who were “rejected due to incurable illnesses, some were abandoned, and others were so-called ‘half-orphans,’ whose parents required temporary assistance while striving to overcome abject poverty or other adversities,” according to NYC Parks.

Finally, there’s the mysterious street known as Old Broadway, a slender unassuming strip that spans 125th to 129th Streets and then picks up again from 131st to 133rd Streets east of regular Broadway. It’s the last piece of Bloomingdale Road.

In the late 19th century, as urbanization arrived in Manhattanville, Bloomingdale Road was straightened and made part of regular Broadway, which became the main north-south thoroughfare. This leftover strip of Bloomingdale Road no longer served a purpose. Rather than de-mapping it entirely, it was renamed Old Broadway—a remnant of a village that’s now often referred to as West Harlem.

[Top image: NYPL; second image: Wikipedia; third image: MCNY, MNY29573; fourth image: NYPL; eighth image: Wikipedia]

January 9, 2022

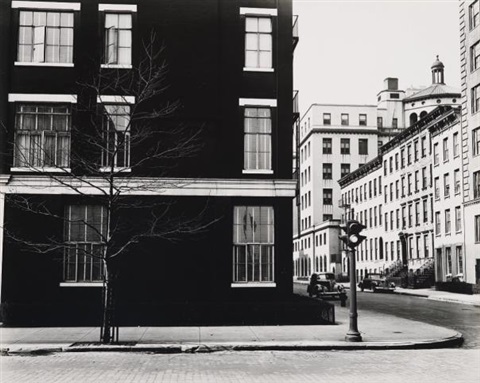

A photographer captures a New York City of abstraction in the 1940s

The street photographers who point their cameras all over the city tend to focus on people in motion in recognizable places—the rush of crowds on a subway platform, barflies at a corner tavern, or the random strollers, workers, loafers, and others found at any moment in time on specific streets and sidewalks.

Brett Weston, on the other hand, used his camera to render a more abstract midcentury city. Instead of focusing on a city of people, energy, and vitality, he isolated ordinary objects and buildings and made them beautiful, haunting, even lyrical.

Weston, born in California in 1911 and the son of photographer Edward Weston, was already an established photographer before coming to Gotham in 1944. During World War II, he was drafted and sent to the Army Pictorial Center in Queens, according to the International Center of Photography (ICP). There, in a former studio owned by Paramount, filmmakers and photographers helped produce army training films. (Today it’s Kaufman Studios in Astoria.)

When he wasn’t working, Weston took to the streets of the city with his 8×10 view camera, per the ICP.

“Over the next two years, Weston took over 300 photographs, each distinguished by an attention to the formal values of linearity, depth, and contrast,” the ICP noted.

“Turning away from the documentary style that characterized much of the photography of New York in the preceding decade, notably Berenice Abbott’s project Changing New York (1939), Weston pioneered a highly subjective and abstract view of the city, often focusing on details such as the finial on an iron railing or ivy on the side of a building.”

The Danziger Gallery, which represents Weston’s work, stated that he “concentrated mostly on close-ups and abstracted details, but his prints reflected a preference for high contrast that reduced his subjects to pure form.”

Weston only spent a few years in New York, and his cityscape images are a small portion of his overall work. In the 1920s he apprenticed with his father in Mexico; most of his life he was based in California, where he had a studio and portrait business, according to The Brett Weston Archive (where his vast body of work can be viewed).

Weston died in 1993 at the age of 82. His New York images have a timelessness that brings them out of the 1940s to still resonate today. Like the work of the abstract expressionist painters of the 1940s, they reflect the quiet, solitary stillness of the modern city.

[First and second photos: artnet.com; third photo: International Center of Photography; fourth photo: artnet.com; fifth photo: International Center of Photography; sixth, seventh, and eighth photos: artnet.com]

Two 1930s tile signs point the way in a Bronx subway station

The B and D stop at Fordham Road and the Grand Concourse in the Bronx isn’t a particularly stunning station.

Opened as part of the IND Concourse Line, the station made its debut during the Depression year of 1933, when transit officials probably weren’t thinking of devoting extra money to beautify an outerborough subway station.

But the station does have two old-timey touches that give it a bit of loveliness and humanity: tile signs letting passengers know which way to go depending on what side of the Grand Concourse—the Bronx’s answer to the Champs Elysees—they needed to get to.

Vintage subway signage like this can still be found on some platforms. Here’s an example at Chambers Street on the West Side, and another at the Cortlandt Street R train stop telling riders where to go to get to the “Hudson Tubes.” And of course, the stop at 14th Street and Sixth Avenue is a treasure trove of forgotten subway signage.

January 2, 2022

This 1930 neon hotel sign still illuminates East 42nd Street

Rising 20-plus stories above 42nd Street, the old-school sign for what was once called the Hotel Tudor is a beacon for Tudor City, the apartment complex mini-city of 12 Tudor Revival-style buildings built in the late 1920s.

Like so many vintage neon signs in New York, its future was threatened. “The sign dates from 1930 when the hotel opened, and has a fleeting brush with demolition in 1999,” according to Tudor City Confidential, a blog that covers the complex. Community opposition helped keep it in place.

Today the hotel is officially known as the Westgate New York Grand Central—and the red glow of the sign lights the way along the eastern end of 42nd Street.

Filling in the ghostly outlines of former buildings in Manhattan

There’s something about New York City in winter that makes ghost buildings come out of hiding. Trees no longer obscure their faded outlines, fewer people on the sidewalks allows for less distraction, and the enchanting late afternoon light throws a spotlight on the forms and shapes we usually miss.

You may have passed some of these phantoms before, but now, in January, they call out to you, wanting to tell their stories. It takes a bit of digging to fill in all the blanks in the current cityscape, but here are some that didn’t ask to be erased.

Above is what remains of 12-14 West 57th Street, remnants of a time when West 57th Street was a residential enclave of elegant, single-family brownstones.

12-14 West 57th Street, 1918

12-14 West 57th Street, 1918Here’s a view of at least one of the brownstones in 1918, already a survivor in a rapidly commercialized West 57th Street.

The outline above is at 13 East 47th Street in the Diamond District, peeking out above the 2-story block of a building that replaced it. In the early 1900s the building was owned by A. Lowenbein’s Sons, Inc., an interior design company whose showroom stood here.

13 East 47th Street, 1920

13 East 47th Street, 1920Here’s the Lowenbein building in 1920. Perhaps the building started out as a brownstone or rowhouse built in the late 19th century, then was converted to commercial use when 47th Street lost its luster as a residential block.

Back on West 57th Street closer to Sixth Avenue is another hole in the cityscape. All that’s left of 32 West 57th is this outline, with the upper floor looking like it was pushed back.

32 West 57th Street, 1939-1941

32 West 57th Street, 1939-1941What a delightful Romanesque Revival house we lost when number 32 met its fate with the wrecking ball! Too bad the outline that remains doesn’t include those top triangular windows.

The ghost building that used to hug 308 West 97th Street is more of a mystery; an image of what stood here was elusive. With its rectangular shape and chimney, my guess is a rowhouse, part of a lovely line built by one developer around the turn of the 20th century, when so much of the new Upper West Side was filled with gorgeous rowhouses.

The phantom outline above is what’s left of several demolished buildings, leaving East 60th Street from Lexington to Third Avenues looking like a toothless smile. Of course it was a residence, a brownstone in a former elite area that became commercialized during the 20th century.

Lexington Avenue and 60th Street, 1930

Lexington Avenue and 60th Street, 1930In this 1930 photo, the corner building that houses Cohen’s Fashion Optical has just been completed. To the right are the uniform residences that decades later were erased (almost) from the cityscape.

[Second image: MCNY, MNY238872; fourth image: MCNY, MN119720; sixth image: NYC Department of Records & Information Services; eighth image: MCNY, MNY240548]

A bronze statue that survived Hiroshima has a message for Riverside Drive

What cements Riverside Drive as one of Manhattan’s most beautiful streets is its architecture. The avenue is a winding line of elegant 1920s and 1930s apartment houses, with some surviving rowhouses and a few stand-alone mansions that reflect the beaux-arts design trend of the Gilded Age—lots of limestone, light brick, and marble.

But every so often, the Upper West Side portion of Riverside has a surprise. Case in point is the 15-foot, 22-ton bronze statue that has stood outside 332 Riverside Drive, between 105th and 106th Streets, since 1955, according to Japan Culture NYC.

The statue is of Shinran Shonin, a Buddhist monk in Japan who founded a sect of Buddhism called Jodo-Shinshu in the 13th century. The monk is depicted in missionary robes, his face mostly obscured by his hat. (Originally he carried a cane, presumed stolen in the early 1980s, per Japan Culture NYC.)

Riverside Drive has always been an avenue of grand statues. But how did the statue of a Japanese monk end up here?

The story begins in Japan in 1937, when a businessman in the metal industry commissioned his factories to make six identical bronze statues of Shinran Shonin, according to fascinating research by Sam Neubauer at I Love the Upper West Side. “The statues were spread across Japan, with one standing on top of a hill overlooking Hiroshima,” Neubauer wrote.

Once war broke out, the Japanese military turned three of the statues into scrap metal for ammunition. “A similar attempt was made in Hiroshima but after significant protests over the importance of the statue, the government allowed Shinran Shonin to remain on his hilltop,” stated Neubauer.

Riverside Drive between 105th and 106th Street, about 1903

Riverside Drive between 105th and 106th Street, about 1903“It was from the hilltop that, on August 6, 1945, the statue witnessed the destruction of Hiroshima when the first atomic bomb exploded over the city,” he continued. “Although the epicenter of the blast was just 1.5 miles away, the statue somehow survived.” An estimated 80,000 people perished in immediate aftermath of the atomic blast.

In 1955, after the New York Buddhist Church moved to Riverside Drive from its original home in a brownstone on 94th Street, the church’s minister and the businessman who commissioned the statue decided to bring it to New York.

“The statue of Shinran Shonin was unveiled in the front garden of the New York Buddhist Church, where it remains today,” wrote Neubauer. “A carved stone plaque along the sidewalk describes the statue as ‘a testimonial to the to the atomic bomb devastation and a symbol of lasting hope for world peace.'”

Apparently radiation was a concern when the statue was unveiled. According to Atlas Obscura, the statue “has been free from radiation since it began its stay in the United States and has never posed a danger to visitors.”

Japan Culture NYC has a slightly different take. “The statue still bears red burn marks on its robes and a trace of radioactivity as a result of the blast from the atomic bomb,” the site stated.

[Third photo: MCNY, MN122632]

December 27, 2021

New Year’s Eve in post-Civil War New York City

It’s 1865 in New York City. The Civil War is over, families are together, and the holiday season is a firmly commercialized event.

Still, I’m not sure what to make of this illustration, from the digital collection of the Museum of the City of New York. Several children stand in front of a store display, their eyes trained on the toys. Meanwhile, a well-dressed woman and girl stand slightly to the side, watching the other kids delight in the window display.

An image of the haves meeting the have nots? It’s a strangely disquieting illustration, with no one else on the sidewalks on what the caption tells us is New Year’s Eve.

[MCNY, 1865, MNY5788]

An Impressionist artist captures the rural feel of early 1900s Upper Manhattan

Throughout his life, painter Ernest Lawson lived in many places. Born in Halifax in 1873, Lawson moved to New York at 18 to take classes at the Art Students League.

“High Bridge at Night, New York City”

“High Bridge at Night, New York City”Over the years he studied and worked in Connecticut, Paris, Colorado, Spain, New Mexico, and finally Florida, where his body was found on Miami Beach in 1939—possibly a homicide or suicide.

“Shadows, Spuyten Duyvil Hill”

“Shadows, Spuyten Duyvil Hill”But if there was one location that seemed to intrigue him, it was Upper Manhattan—the bridges and houses, the woods, rugged terrain, and of course, the rivers.

“Ice in the RIver”

“Ice in the RIver”From 1898 to about 1908, while fellow Ashcan School artists focused their attention on crowded sidewalks and gritty tenements, Lawson lived in sparsely populated Washington Heights, drawing out the rural beauty and charm of the last part of Manhattan to be subsumed into the cityscape.

“Boathouse, Winter, Harlem River”

“Boathouse, Winter, Harlem River”“Less committed to social realism than his peers, his works are more remarkable for their treatment of color and light than their social relevance,” states the National Gallery of Canada.

“A House in the Snow, the Dyckman House”

“A House in the Snow, the Dyckman House”Lawson’s Upper Manhattan is an enchanting, often romantic place, which he rendered in “thick impasto, strong outlines, and bold colors,” according to Artsy.com. His nocturnes reflect the seasonal beauty of still-extant spots like the High Bridge, Harlem River, Spuyten Duyvil, and the Dyckman Farmhouse (the last Dutch colonial-style farmhouse in Manhattan).

“The Harlem River (Rivershacks)”

“The Harlem River (Rivershacks)”Though one critic described him as “a painter of crushed jewels,” according to the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA), and another noted his “peculiar power of finding sensuous beauty in dreary places,” Lawson never found fame like Ashcan painters George Luks and John Sloan.

Portrait of Ernest Lawson by fellow Ashcan artist William Glackens

Portrait of Ernest Lawson by fellow Ashcan artist William Glackens“Despite great acclaim from certain critics, Lawson remained under-appreciated in his lifetime, and was often depressed and struggling financially,” per PAFA. His name may not be well-known, but Lawson captured the mood and feel of Upper Manhattan’s landmarks and landscape just before urbanization arrived.