Esther Crain's Blog, page 58

November 7, 2021

A woman found bludgeoned in a Tenderloin hotel sparks a trial that riveted New York

It happened on Broadway and 31st Street in room 84 of the Grand Hotel, in the middle of the Tenderloin—Gilded Age New York’s vast vice playground of brothels, dance halls, theaters, and gambling dens.

After knocking on the door several times on the morning of August 16, 1898, a chambermaid entered the room and found the corpse of a pretty young woman, her head in a pool of blood and her clothed body spread out on the floor.

The stylishly dressed woman “had been bludgeoned with a lead pipe to the skull, her neck was broken, and one of her earlobes was torn by the violent removal of an earring,” wrote John Oller in Rogues’ Gallery: The Birth of Modern Policing and Organized Crime in Gilded Age New York.

“Her clothing was undisturbed, the bed linens fresh and unmussed,” wrote Oller. “On a table in the center of the room stood an empty champagne bottle and two glasses.”

Police in the Tenderloin were used to gruesome crime scenes, and they were summoned to the hotel to piece together evidence.

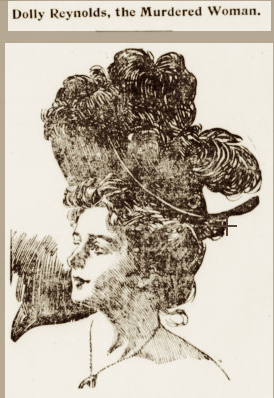

The details were intriguing. Though the woman had signed into the hotel as “E. Maxwell and wife, Brooklyn” and was then seen by hotel staff meeting a man in a straw hat, her real identity was Emeline “Dolly” Reynolds, a petite 21-year-old who two years earlier left her well-off parents in Mount Vernon to try to make it as an actress in Manhattan.

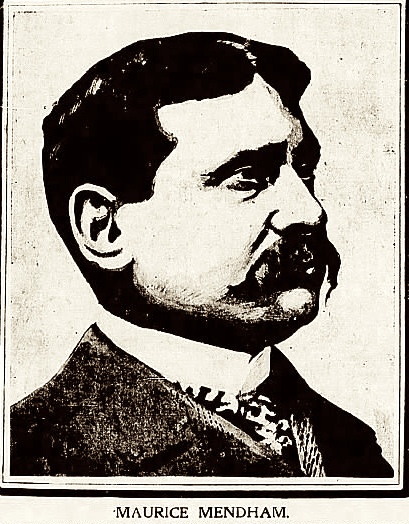

Reynolds wasn’t getting anywhere as an actress however. For a time she sold books, then met a married man named Maurice Mendham (above). This wealthy stockbroker helped set her up in an apartment on West 58th Street, bought her jewelry, and lived with her “as man and wife,” as a prosecutor later put it.

Just as interesting to detectives was the check that fell out of her corset during her on-scene autopsy. “It was made payable to ‘Emma Reynolds’ in the amount of $13,000,” wrote Oller. “Dated August 15, 1898, the previous day, it was drawn on the Garfield National Bank, signed by a ‘Dudley Gideon,’ and endorsed on the back by ‘S.J. Kennedy.'”

Investigators soon learned that Mendham had an alibi; he was in Long Branch at the time. They also discovered that ‘Dudley Gideon’ didn’t exist. But S.J. Kennedy did, and they began taking a closer look at this 32-year-old Staten Island dentist who practiced on West 22nd Street and was introduced to Reynolds by Mendham.

“Reynolds’ mother told police that about a week before the murder, Dolly told her that Dr. Kennedy (above) volunteered to put $500 on a horse race for her,” according to Strange Company. “She had drawn the money from her bank, and would meet him on the evening of August 15 to deliver what he promised would be a highly profitable investment.”

Police arrested Kennedy five hours after Reynolds’ body was discovered.

After denying he knew Reynolds, Kennedy then admitted to being her regular dentist, according to Oller, and that he saw her in his office the previous week. He insisted their relationship was professional and that he did not place any bets for her, had never been to the Grand Hotel, and his signature on the $13,000 check was forged.

Still, hotel employees ID’d him as the man in the straw hat they saw with Reynolds the day before her body was found. Kennedy also could not explain his whereabouts at the time of the murder, estimated to be at 1 a.m. He thought he’d been to Proctor’s Theatre on West 23rd Street (above), but he couldn’t recall the name of the play he’d seen, wrote Oller.

Police and prosecutors came up with a theory to connect Kennedy to Reynolds. “According to the theory, Dolly was just one of the ‘lambs’ that Kennedy, a feeder for a group of confidence men, was tasked with separating from their money,” explained Oller. But there were some holes, such as why the check was for $13,000, and why the dentist murdered her so viciously.

The March 1899 trial riveted New York City, and newspapers printed lurid front-page headlines with illustrations of the courtroom. Hotel staff and guests (like Mrs. Logue, above) took the stand; Kennedy did not. The jury quickly convicted Kennedy and sentenced him to die in Sing Sing in the electric chair.

But then, the convicted dentist got a lucky break, when in 1900 the Court of Appeals granted him a new trial due to “hearsay” that was used as evidence in the first trial.

The second time, the jury deadlocked, with 11 voting to acquit. At a third trial, Mendham testified, and “his evasiveness about the extent of his relationship with Dolly Reynolds fed the defense’s insinuation that he was somehow behind the murder,” wrote Oller.

While crowds sympathetic to Kennedy rallied outside the courtroom, the jury couldn’t agree on a verdict once again. The city declined to try the case a fourth time. Kennedy was and returned to Staten Island to a hero’s welcome.

“He resumed his dental practice and lived quietly in New Dorp, dying at age 81 in August 1948, almost 50 years to the day after the murder of his patient Dolly Reynolds,” wrote Oller.

[Top image: San Jose Mercury News; second image: MCNY X2011.34.35; third image: New York World; fourth image: The Scrapbook; fifth image: MCNY 93.1.1.15639; sixth image: New York World; seventh image: New York Journal]

From brownstones to business: 3 centuries on a West 57th Street block

New York City developers went on a brownstone-building frenzy from the 1860s and 1880s. Block upon uptown block began teeming with these iconic row houses that first symbolized luxury but eventually were derided for their mud-brown monotony.

West 57th Street from Fifth to Sixth Avenue was one such brownstone block. Here it is around 1890, about the time when this fashionable stretch south of Central Park was home to wealthy residents with names like Roosevelt, Auchincloss, and Sloane, according to Edward B. Watson in New York Then and Now.

Interrupting the low-rise block are church spires. “The church with the tall spire between Sixth and Seventh Avenues is the Calvary Baptist Church, built in 1883,” wrote Watson. Beyond the Sixth Avenue El is the 11-story Osborn apartment building, constructed in 1885, and the faint spire of the wonderfully named Church of the Strangers.

What’s not in the photo on the right at the corner of Fifth Avenue extending all the way to 58th Street is the Alice Vanderbilt mansion—where the widow of Cornelius Vanderbilt III lived until the 137-room Gilded Age relic was torn down in 1927 (above, in 1894, with brownstones looming on the left).

Fast forward 85 years to the 1970s. In the 1975 photo of the same block (below), West 57th’s days as a stylish residential enclave were mostly over.

Brownstones were bulldozed in favor of tall commercial buildings, including the curved reflective glass tower at Number 9 (completed in 1973, per Watson). The Sixth Avenue El is just a memory.

And though luxury residences like the Osborn survived (visible at the way far left, I believe, if you really squint), few brownstones made it. One in the photo to the right of the reflective glass tower is 7 West 57th Street. This is the former home of financier and philanthropist Adolph Lewisohn, according to Watson, though the facade has undergone a redesign.

Lewisohn might best be remembered as the man who funded CUNY’s Lewisohn Stadium between Amsterdam and Convent Avenues from 136th to 138th Streets, which met the bulldozer in 1973.

Here’s the same stretch of West 57th Street today, with traffic, glassy towers, and many empty spaces where brownstones and other lower-rise buildings used to be.

Bergorf-Goodman has long since taken the place of the Vanderbilt mansion at the corner of Fifth, Lewisohn’s home is either swathed in black glass or gone altogether, and supertall luxury condos stretch higher than the ambitious builders of the Osborn could have imagined.

[Top photo: New York Then and Now; second photo: New-York Historical Society; third photo: Edmund V. Gillon, Jr/New York Then and Now]

October 31, 2021

A moment in time somewhere on the Bowery

An abandoned street cleaning cart. Men in hats walking alone. A streetcar traveling on dusty Belgian block pavement, an elevated train overhead, a succession of store signs and advertisements.

It’s just a glimpse in time around the turn of the century on the Bowery. But where, exactly? One of the buildings has 57 on it, suggesting 57 Bowery. That address no longer exists; it would have been near the entrance of the Manhattan Bridge.

There’s another sign that might give us a clue: the ad propped against a pole at the edge of the sidewalk. It looks like the first word is “London.” A theater with that name existed at 235 Bowery, where the New Museum is today between Stanton and Rivington Streets.

Whatever the exact address is, you can practically feel the energy and vitality—the pulse of a street now synonymous with a lowbrow kind New York life.

The story of the hidden garden inside a Turtle Bay tenement block

East 49th Street between Second and Third Avenues in Turtle Bay is a block with a backstory.

During the 17th century, this was farmland owned by Dutch settlers; in the 18th century, a stagecoach stop on Boston Post Road was established here. By the Civil War, the farms vanished, subsumed into the urban city and turned into brownstones and tenements.

But the story in this post concerns something that came to Turtle Bay in 1946: a hidden romantic garden of shady trees, decorative flower pots, stone block walls and paved walkways unseen from the street and accessed through a thin-slatted iron gate.

That courtyard, Amster Yard, was the brainchild of interior decorator James Amster (below). Two years earlier, Amster had heard that a cluster of buildings on East 49th Street were for sale. Constructed around 1870, the buildings were now dilapidated and the neighborhood not quite as desirable as it once had been, especially with the elevated train still roaring along Third Avenue.

Amster purchased these buildings, which included “a boarding house, a carpenter’s workshop and the home of an elderly woman with 35 cats,” according to a New York Times article from 2002.

He then enlisted the help of friends to “create a garden complex surrounded by offices and apartments renovated from the shells of the original buildings,” wrote Pamela Hanlon in Manhattan’s Turtle Bay: Story of a Midtown Neighborhood.

The result: “a picturesque cluster of one- to four-story brick houses around an L-shaped garden courtyard filled with trees and shrubbery,” stated the New York Times in 1986.

“You go through a thin-barred iron gate down a long flagged corridor till you’re midway between the north side of 49th Street, but perhaps 40 feet short of 50th Street, and you’re in a cool, ailanthus-shaded garden restored to look much as it was, say, 150 years ago,” wrote a New York Times reporter in 1953.

Amster Yard was also something of an artists’ enclave, home to interior designer Billy Baldwin and sculptor Isamu Noguchi.

In the 1960s, Amster Yard became a New York City landmark, a “pleasant oasis in the heart of Manhattan” that altered the original buildings but recreated the feel of an Old New York garden. Amster himself was a presence there until he died at age 77 in 1986.

Amster Yard still exists, and it’s semi-open to the public. But while today’s Amster Yard looks like the courtyard James Amster designed, it’s actually a recreation.

In the early 2000s, Amster Yard’s new owner, the nonprofit cultural group Cervantes Institute, found that the buildings surrounding the garden were structurally dangerous. The group decided to demolish them, then built reproductions.

Wander into Amster Yard now, and you’ll experience an illusion of Amster’s buildings, which were recreations of the original dilapidated circa-1870 houses. It’s a little convoluted, but the courtyard itself is romantic and delightful, a peaceful respite that blocks the sounds of the modern city.

It’s not the only lovely garden hidden from the street in the neighborhood. Turtle Bay Gardens, a collection of 19th century rowhouses restored for the elite in the 1920s, also has a secret garden…but that one is residents-only.

[Third photo: Wikipedia]

October 25, 2021

The unusual clock hands on a Third Avenue union sign

I must have passed the sign for the Metallic Lathers Union on Third Avenue in Lenox Hill a hundred times before finally noticing it the other day.

There’s a little history on it: the current union came out of an original union of wood, wire, and metal lathers workers that was organized in 1897. But what really caught my eye was the street clock attached to the sign, with its streamlined, Art Deco look.

The clock hands could be tools of some kind, perhaps a tool a lather might use? (A lather installs the metal lath and gypsum lath boards that support the plaster, concrete, and stucco coatings used in construction.)

This lathe cutter looks something like the clock hands. Maybe it’s a stretch, but perhaps the clock reflects something about the work these union members do in an industry vital to the growth of the city.

October 24, 2021

These ‘automobile stables’ on 75th Street might be the city’s first garages

Back in the days when New Yorkers got around town by horse and carriage, wealthy Gothamites built separate private carriage houses blocks away from their own mansions.

Inside these carriage houses (many quite lovely), broughams and phaetons were parked and horses cared for. In a small second or third floor area, a coachman and groom could live and work, making sure the carriage was ready when the owner wanted to use it.

By the turn of the century, however, the motor car hit the scene. Though some thought these “devil wagons” were just a fad, others realized they would soon replace horses and become the preferred mode of transportation for posh city residents (who were the only people who could afford a car at that time).

In 1902, a man named Edmund C. Stout was one who saw the future. That year, Stout bought five brownstone houses at 168-176 East 75th Street and converted them into what he dubbed “automobile stables,” according to a 2013 paper by Hilary Grossman from the Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture.

“Soon after completion, they were noted in the New York Times as the first automobile garages erected for private use in the city,” stated the Upper East Side Extension report by the Landmarks Preservation Committee.

Stout gave his automobile stables an architectural makeover, adding a fourth floor, removing the stoops, and trading the out-of-fashion brownstone style for a more arts and crafts look with fanciful rustic red brickwork.

“The buildings were sold off to New Yorkers who sought a place to keep their automobile and house their chauffeur,” wrote Christopher Gray in a New York Times column from 1988. “Each building originally had a charging station for electric automobiles.”

The automobile stables weren’t just for cars. The LPC report had this to say: “According to the New York Times, each building was initially outfitted with ‘a living room, which the owner may use if he feels so disposed, a dining room, and small kitchen, in which suppers or light meals may be prepared, and a billiard room.’ Other sources indicate that the upper-stories may have actually housed the private chauffeurs of the owners.”

Who were these owners? Millionaire C.G.K. Billings owned number 172, per the LPC report; Billings is best remembered as the man who arranged a black tie dinner party on horseback at Sherry’s in 1903. George F. Baker, a financier and philanthropist, owner number 168. Banker Mortimer Schiff purchased number 174.

Though the popularity of automobiles soared in the early 1900s, some of the automobile stables were converted for other uses. By 1912, number 172 was thought to have been used for an embroidery business, according to the LPC report. Numbers 172 and 176 may have been turned into residences.

Number 176 housed a physician’s office for more than a decade, from 1966 through 1979, per the LPC report, “while number 172 hosted a number of different businesses simultaneously in 1964, including an antiques store, custom dress-making store, and

artist studios.”

Today, the five former automobile stables are residential units, and only numbers 168 and 174 still have a first-story garage, the LPC report states.

A small number of Manhattanites are lucky enough to have private garages, including the owners of the house next door to this row at number 178—the rest do without or fork over big bucks to park underground.

[Fifth photo: NYC Department of Records and Information Services]

October 18, 2021

There’s a lot going on outside the Third Avenue Railroad Depot in this 1859 painting

Sometimes a painting has so much rich detail, it just knocks you out. That was my reaction to this magnificent scene of the Third Avenue Railroad Depot between 65th and 66th Streets, painted two years after the depot opened in 1857.

Amazingly, the painter of this “precise representation” of the depot, William H. Schenck, was also the company’s superintendent, according to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which owns the work.

In 1859, this stretch of what would become the Upper East Side (near the Treadwell Farm Historic District) was mostly untouched by developers, though some wood houses are off in the distance. Street lamps stand on corners, however, and the road looks paved.

The streetcars pulled by horses follow the rails in and out of the depot. People are scattered about; some are on horseback, and one man steers a wagon full of goods. A hot air balloon sails through the sky, what’s that about?

“In addition to highlighting the contemporary popularity of the horse-drawn streetcar, Schenck also included a hot-air balloon in the sky, identified in tiny letters as the Atlantic,” the Met states. “The balloon’s owners, John Wise and John LaMountain, hoped to fly it across the Atlantic Ocean to initiate an entirely new form of transportation, but they never succeeded.”

Sadly, the Third Avenue Railroad Depot was destroyed by fire four years later.

The story of the house-size rock between two apartment buildings off Riverside Drive

West 114th Street between Riverside Drive and Broadway is a quiet sloping block of light brick rowhouses, similar to other side streets in the area.

But there’s one massive difference that sets West 114th apart: the 100-foot rock lodged between two houses and walled off behind an iron fence.

This hulk of Manhattan schist was nicknamed Rat Rock years ago by locals, who were understandably spooked by the rodents that used to enjoy nesting there, according to a 2000 New York Times article.

Like all the rock outcroppings found in Manhattan, the story of Rat Rock began hundreds of millions of years ago, when the bedrock that helps support skyscrapers was formed. Manhattan schist is a type of bedrock, and while most bedrock lurks beneath ground, geological fault lines forced some rocks to the surface, The Times piece explains.

Having big boulders above ground wasn’t a problem in Central Park. Though some were dynamited away when the park was being built, others were left behind to provide a rustic feel amid the lake, pond, and pastures.

Rat Rock in 1917

Rat Rock in 1917But when developers encountered rocks like this on the street grid, they either blasted them away or left them alone. For unknown reasons—perhaps because it’s just so enormous—Rat Rock remained, and builders worked around this break in the streetscape.

Apparently, it’s here to stay. The land is owned by Columbia University, and they have no plans to get rid of it. “The lot and development rights are incredibly valuable, but removing the rock could cost hundreds of thousands of dollars,” states The Times.

Enormous boulders like this didn’t get in the way of nearby development a century or so ago, however. The Museum of the City of New York has this 1903 photo in its collection of a similar rock thwarting the building plans of a row of houses on Riverside Drive between 93rd and 94th Streets.

I’m not so sure this photo is labeled correctly; it doesn’t look like the Riverside Drive of the era to me. But assuming it is, the rock has long been removed.

Over on the East Side, this undated photo shows rock outcroppings at Fifth Avenue and 117th Street, with modest houses built on top of them far off in the distance. The rocks here are no longer.

Riverside Drive is one of New York’s most historic (and beautiful!) streets. Join Ephemeral New York on a walking tour of the Drive from 83rd to 107th Streets on October 24 that takes a look at the mansions and monuments of this legendary thoroughfare.

[Third image: New-York Historical Society; fourth image: MCNY x2010.11.3102; Fifth image: MCNY 93.91.367]

October 17, 2021

The faded ad that sent newcomers to the Hotel Harmony in Morningside Heights

So much of New York’s past can be gleaned from the faded ads on the sides of unglamorous brick buildings. Weathered by the elements but still somewhat legible, they featured a product, a place, or a service that offers a bit of insight into how city residents once lived.

Case in point is the wonderfully named Hotel Harmony. The color ad for this “permanent and transient” hotel can be seen on Broadway and West 114th Street.

Based on the ad, the Harmony sounds like a run-of-the-mill hostelry aiming to come off as a little high class, especially with that tagline, which is supposed to say “where living is a pleasure,” per faded ad sleuth Walter Grutchfield.

The Hotel Harmony in 1939-1941

The Hotel Harmony in 1939-1941The actual Hotel Harmony was a few blocks away at 544 West 110th Street. The tidy brick and limestone building first served as the headquarters of the Explorers Club, but by 1935 it was converted into a hotel, according to Landmark West!

What kind of people lived or stayed here? Based on how little activity from the hotel made it into newspapers of the era, I’m going to guess quiet types who blended into the neighborhood. Robbers held up the night manager in the 1950s and made off with cash; a resident described as a limo driver died at Knickerbocker Hospital, then on Convent Avenue in Harlem; his obituary stated.

The Hotel Harmony has been defunct since the 1960s, when Columbia University bought the building and converted it into a dormitory fittingly called Harmony Hall, Landmark West! reported. The repurposed hotel remains…and so does the spectacularly preserved sign that sent many visitors to the hotel’s doors for days, weeks, perhaps years.

[Second image: NYC Department of Records and Information Services; third image: BWOG Columbia Student News]

October 11, 2021

Going back in time to 1930s Columbus Circle and Central Park

Whatever you think of Christopher Columbus, you have to admit the circle named for him at 59th Street looks pretty spectacular in this 1934 postcard.

It’s a rich and detailed view looking toward Central Park South and into the park itself. There’s the Columbus monument, the Maine monument at the entrance to the park (no pedicab traffic, wow!), the Sherry Netherland hotel all the way on Fifth, and a streetcar snaking its way to Broadway.

[postcard: postcardmuseum]