Esther Crain's Blog, page 61

September 5, 2021

This modest Forsyth Street walkup was once a synagogue

Forsyth Street between Grand and Hester Streets is a pretty typical Lower East Side block, with an uneven row of shabby but serviceable tenement walkups lining the east side of the street along Sara Roosevelt Park.

But one of those walkups, number 80, has some curious architectural touches. The third floor of the three-story building features Gothic arched and circular windows; you can almost imagine them filled with stained glass. And iron stars of David decorate each fire escape landing.

There’s good reason for these design flourishes. Though 80 Forsyth was built in 1874, according to 2013 post in The Lo-Down, what was once a house or tenement was converted into a synagogue in the late 19th century.

Turning a residential or commercial space into a synagogue may not have been unusual at the time. (Just as it’s not so unusual now, with storefront churches.) In the 1880s and 1890s, the Lower East Side was filling up with thousands of Jewish immigrants, who formed or joined congregations and needed places to worship.

Several congregations used the synagogue over the years. In the 1880s, a congregation identified by The New York Times as Kol Israel Anschi Poland occupied the space. The Times wrote that the congregation was fighting a tax bill from the city because the property was used for religious purposes, the congregation asserted.

But the city won the case, convincing the judge that since the ritual baths in the basement were open to “all Hebrews,” not just congregants, the building was liable to taxation.

I’m not sure when the last congregation abandoned the building. But this 1939-1941 tax photo of 80 Forsyth (above) appears to have a commercial tenant on the ground floor. (There’s the stained glass; if only the photo was in color!)

In the 1960s, the house turned synagogue took on an entirely new life: It became the studio of Abstract Expressionist painter Pat Passlof, per The Lo-Down.

Passlof bought the building in 1963 for $20,000 with her husband, painter Milton Resnick, and help from her parents, who pronounced it a “rat hole,” according to a 2011 New York Times piece.

“They called it a rat hole, but I couldn’t deny that,” Passlof said in the Times article. She was 83 and died later that year.

In 2014, the ex-synagogue went on the market for $6,250,000. Number 80 Forsyth has returned to its original purpose as a residence, it seems.

[Third image: NYC Department of Records and Information Services]

The last colonial-era mile marker remaining on a Manhattan Street

Traveling to and from New York by land in the 1700s was not for the faint of heart. The city of about 18,000 people was generally huddled around or below Wall Street, and the few roads that ran north through the wilds of Manhattan were primitive and hazardous.

To help guide hearty travelers by foot, horseback, and stagecoach, city officials installed a series of stone mile markers on the Old Post Road that let people know how far they were from city hall.

The Old Post Road, or King’s Highway, as it was known before the Revolutionary War, followed a preexisting Native American trail into today’s Westchester and then up to Albany or Boston. As its name indicates, the road was used for mail delivery, and Postmaster Benjamin Franklin himself supervised the placing of the mile markers.

Over the years, the mile markers—the first at Rivington Street and the Bowery, and the last in the Bronx near Spuyten Duyvil, according to a 1915 document from the City History Club—disappeared from the streetscape.

Yet one of these “battered and broken milestones,” as an 1895 Sun article put it, still exists today in Upper Manhattan. Amazingly, it’s embedded in a stone retaining wall just steps from Broadway and 213th Street.

The milestone, which used to tell travelers that they were 12 miles from the main city, has been part of this stone wall (photo, about 1910) since the end of the 19th century.

How did it end up here? Well, this wasn’t the milestone’s original exact location. According to the Sun, it used to stand on a nearby road called Hawthorne Street, which is the former name of 204th Street.

When construction crews were building roads and otherwise modernizing Inwood, they came across the mile marker that had outlived its purpose. William Isham, a wealthy leather merchant and banker with a nearby estate and mansion (above), took the mile marker and had it embedded into the wall.

“Mr. Isham had the stone marker moved and installed in the wall next to his gate when it was tossed aside by road workers on Broadway,” explains NYC Parks.

“When roadway workers were removing a red sandstone mile marker, William Isham had it installed at the right side of his entrance gate on Broadway,” echoed the Historic Districts Council.

After Isham’s death, his family donated the land from his estate, including the retaining wall with the mile marker, to the city in 1911 to create Isham Park.

Sadly the 12-mile marker has lost its inscription. But it’s still an amazing remnant of the early days of Gotham, when getting far out of the main part of town could be treacherous and disorienting.

Though it’s the only milestone technically on a Manhattan street, there’s at least one other Old Post Road mile marker preserved in Manhattan: the 11-mile marker. It’s on the grounds of the Morris-Jumel Mansion on 160th Street near St. Nicholas Avenue and is noted with a small plaque.

Brooklyn, on the other hand, has its own mile marker relic still visible on a street. (Or at least it was several years back.) A stub of granite with the number 3 carved into it is on Ocean Parkway and Avenue P. That’s 3 as in three miles to Prospect Park, where Ocean Parkway begins.

[Top image: Wikipedia; second image: New-York Historical Society; third image: NYC Parks via Volunteers for Isham Park; fourth image: Wikipedia]

August 30, 2021

What John Sloan painted after “loafing about Madison Square”

Ashcan painter John Sloan is the master of the city scene, infusing seemingly uneventful interactions with dense imagery and narration that presents a deeper story.

“Recruiting in Union Square,” from 1909, is a haunting example of this. But it took some lounging around another New York City park for Sloan to get the inspiration to capture the scene.

“Of this piece, the artist wrote that he, “loafed about Madison Square where the trees are heavily daubed with fresh green and the benches filled with tired bums,” states the Butler Institute of American Art, which has the painting in its collection.

“After mulling about this scene for several days, Sloan finally began his painting of a city square where Army recruiting signs stood among several vagrants who he called ‘bench warmers.'”

No word on why Sloan seemed to move the scene he found in Madison Square to Union Square, but he would have crossed paths with both parks regularly. After moving to Manhattan from Philadelphia in 1904, he and his wife moved around Chelsea and Greenwich Village.

“Although he claimed he tried to keep his political views out of his art, Sloan painted Recruiting a mere six months before becoming a member of the Socialist Party,” according to the Butler Institute. “Perhaps it was this pursuit of personal freedom that ultimately encouraged Sloan to become a member of Henri’s infamous group known as ‘The Eight,’ who rebelled against the popularity and academia of The National Academy of Design.”

New York City’s oldest public school is in this 1867 building in Greenpoint

With its red brick facade, ornate entryway, and cathedral-like windows, Public School 34 in Greenpoint is a Romanesque Revival-style beauty.

But this elementary school that truly looks like a school also makes history.

Built in 1867 on Norman Avenue two years after the Civil War ended and President Lincoln was assassinated, it’s one of the oldest, and by some claims the oldest, public school building in New York City that’s still in use today.

Also called the Oliver H. Perry School—after the naval officer who helped defeat the British during the War of 1812—the building (below, in 1931) is rumored to have done a stint as a Civil War hospital.

“Walking inside the buildings long hallways, they certainly have the feel of hospital wards,” stated Geoff Cobb, a writer at Greenpointers.com, in 2016. “There are no four-walled classrooms, instead the long ward like halls have been divided up, but it is not hard to imagine that the building was once filled with wounded union soldiers.”

The Landmarks Preservation Commission report that designates PS 34 a historical landmark doesn’t mention a hospital, though. Instead, it calls out the architectural loveliness of the school, as well as that it was built to serve a recently urbanized Greenpoint thanks to the booming shipbuilding industry along the East River.

It’s not a surprise that Brooklyn maintains such an early school building; the borough—which of course was a separate city at the time—was an educational leader back in the 19th century.

“Public education began in Brooklyn in 1816 and by the late 19th century had grown to the point that Brooklyn had one of the most extensive public education systems in the country,” wrote Andrew Dolkart in Guide to New York City Landmarks.

Today, PS 34 is a neighborhood school with a Polish-English dual language program, a reflection of the Polish immigrant community in Greenpoint. The site Brooklyn Relics has more gorgeous photos.

[Top photo: Wikipedia; second photo: NYPL; third and fourth photos: Brooklynrelics]

August 29, 2021

The 18th century farm lane preserved in a Riverside Drive courtyard

The mostly unbroken line of elegant apartment buildings along Riverside Drive on the Upper West Side appear from afar like early 20th century residential fortresses.

But look closely past the black iron fence at one building on the corner of 92nd Street. You’ll catch a glimpse of a sliver of colonial-era Manhattan that isn’t on modern-day maps and doesn’t adhere to the circa-1811 street grid.

The 7-story residence is 194 Riverside Drive (below), completed in 1902 and designed by Ralph Samuel Townsend, an architect who lived on 102nd Street and designed buildings all over the city—including the richly detailed Kenilworth on Central Park West.

“The wide alleyway on the south side of the building is the remnant of a path or lane that once led from the old Bloomingdale road (slightly off line with Broadway) to Twelfth Avenue,” wrote the Landmarks Preservation Commission in their 1989 report designating this stretch of Riverside Drive a historical district.

The unnamed lane, which runs on the north side of 190 Riverside next door, “separated the farms of Brouckholst Livingston to the south and R.L. Schieffelin to the north.”

These farms and others were part of the village of Bloomingdale (image above), a once rural swatch of today’s Upper West Side that served as farmland, then the site of estates and institutions, and by the late 19th century was absorbed into the larger city.

An 1890s map of the neighborhood (below, click the link to zoom in) shows us exactly where this farm lane once ran.

Between 91st and 92nd Streets, you can see faintly outlined blue lines going from the river to the former Bloomingdale Road—which opened in 1703 and offered access to and from the rest of Manhattan to this beautiful part of Gotham. (Bloomingdale came from the Dutch Bloemendaal, which meant “valley of flowers.”)

Today, the lane would extend from the courtyard on the south side of 194 Riverside Drive, through the backyards of row houses past West End and Avenue. Google maps allows us to trace the path, and then imagine the colonial-era farmers and estate owners who traversed it centuries ago.

[Second image: Wikipedia; third image: NYPL; fourth image: LOC]

August 22, 2021

Vintage store signs from the 1970s live on in Astoria

Astoria is known for its low-key neighborhood vibe, Greek food, beer gardens….and some very atmospheric vintage store signs on the main drag of 31st Street that look time-capsuled from the 1960s and 1970s.

It’s hard to beat this charming, no-frills sign from Rose and Joe’s, a traditional Italian bakery (and pizza place). The bakery has been at this address since the 1970s; previously it operated on the corner of 31st Street and Ditmars, per queensscene.com.

Housewares shop King Penny has a mom and pop neighborhood store feel to go with the old-school signage and striped fabric awning. Psychic readings, why not?

The Fabric Center sign just gives it to you straight in big bold red letters and a few details in blue. Based on the sign, I’d guess this business has been here since the 1970s, but I found no corroborating information.

Ferrari Cleaners has a horizontal sign over the entrance that may not be nearly as old as the vertical one attached to the facade on the second floor.

La Guli Pastry Shop is another stunner: the classy cursive lettering, slightly torn fabric awning, the curves in the display windows.

It’s hard to guess how old the sign is. But the folks behind La Guli have been running it in this location since 1937, and the current owner actually grew up in the apartment above the store, according to their website.

The Medieval-like reformatory for “fallen” women on Riverside Drive

In 19th century New York, benevolent societies began springing up. These groups were typically founded by religious leaders or citizens of means to help the less fortunate or end a social evil like alcoholism, gambling, and prostitution.

The Magdalen Asylum in an undated photo

The Magdalen Asylum in an undated photoAmong these new organizations was the New York Magdalen Benevolent Society, launched in 1830. The Society’s mission, according to 1872’s New York and Its Institutions, was to promote “moral purity, by affording an asylum to erring females, who manifest a desire to return to the paths of virtue, and by procuring employment for their future support.”

In other words, the Magdalen Benevolent Society catered to “fallen women,” so-called “magdalens” who found themselves in the clutches of vice and needed to be reformed.

The asylum building in 1915, surrounded by the Riverside Drive extension and new apartment buildings

The asylum building in 1915, surrounded by the Riverside Drive extension and new apartment buildingsIn the 1830s, the Society took over the upper floors of a building on Carmine Street and then moved to a larger site far from the city center at Fifth Avenue and 88th Street.

By the late 19th century, the group was looking for new quarters for the 50-100 women they took care of at any one time, who ranged from 10 to 30 years old, states the 1872 guidebook.

In the 1890s, a larger space for a new asylum far out of town in West Harlem was secured. Built specifically for the Society between 138th and 139th Streets, this secluded, fortress-like institution overlooked the Hudson River.

“Designed by architect William Welles Bosworth (1869-1966), the attractive neo-medieval building stood on extensive grounds that led all the way to the edge of the island where railroad tracks traced the Hudson River,” wrote Bronx Community College’s Andrea Ortuño, PhD, in a post for Urban Archive.

“The new building included room for 100 inmates as well as a chapel. Adjacent to the chapel was a separate building that functioned as a laundry––the proceeds from which partially supported the operation of the Magdalen Asylum.”

The “inmates” (a word used at the time for anyone living in an institutional setting, not just prison) worked the laundry and attended prayer sessions. They also made headlines when they escaped, as these two Evening World articles from June and July 1894 attest.

Slated for demolition in 1961

Slated for demolition in 1961The asylum on 139th Street was short-lived. “Despite the Magdalen Asylum’s uptown relocation, continued urban development, namely plans to extend Riverside Drive, had an adverse impact on the isolation of inmates,” wrote Ortuño.

“In order to maintain the city’s grid of streets, 139th had to be extended to meet the path of Riverside Drive and hemmed in the south side of the building. The wide sidewalks planned for the east side of Riverside Drive abutted the rear of the asylum and would eventually expose the female inmates to all manner of passersby on the street.”

A replacement is announced: a new apartment complex

A replacement is announced: a new apartment complexThe Magdalen Benevolent Society thought it better to relocate once again. By 1904 they’d left for a more remote location in Inwood. Stories of dramatic escapes on the part of the inmates at this new spot, later renamed Inwood House, have been collected from newspaper archives by myinwood.net.

The former asylum building was then turned into the House of the Holy Comforter, which accommodated “incurables,” according to a 1905 New-York Tribune article. After a period of abandonment, the asylum was knocked down in the early 1960s. An apartment complex called River View Towers is on the site now…and no trace of the fallen women once sent there remains.

Riverside Drive has a fascinating history. Join Ephemeral New York on a walking tour Sunday, August 29 that explores the history of Riverside Drive’s mansions, monuments, and more!

[Top photo: New-York Historical Society; second image: MCNY F2011.33.53; third image: Evening World; fourth image, Evening World; fifth image MCNY x2010.11.3146; sixth image: x2010.11.3145]

Deconstructing a 1905 view of East 14th Street

Not much from the 19th century remains today on East 14th Street between Fifth Avenue and University Place. On the north side, a 1960s white brick apartment residence dominates the block; on the south, two black-glass buildings frame a string of chain stores.

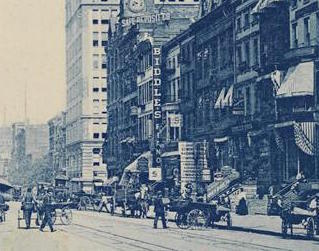

14th Street looking West toward Fifth Avenue, about 1905

14th Street looking West toward Fifth Avenue, about 1905But what a different scene it was around around 1905 (above), when a publishing company produced this postcard! This difference between then and now reveals a lot about the changes that came to this stretch of 14th Street just west of Union Square.

For starters, the sign on the right for “Biddles Piano” is a reminder that the block was firmly in New York’s first piano district, and 14th Street near Union Square was piano row.

In the late 19th century, having a piano in your brownstone parlor was a status symbol; player pianos later came on the market and became wildly popular. Steinway & Sons led the way on 14th Street in 1864, opening a showroom at Fourth Avenue. More piano company showrooms followed, including Estey, Steck, Wheelock, and Biddle.

The “no pain” sign on the lower left is also a relic of an era when dentistry was an emerging profession, and getting a tooth extracted even in a dentist’s office was a risky venture. People at the turn of the century were terrified of the possibility of pain, so dentists made a point of advertising no-pain procedures.

The sign for Japanese Art on the left reflects the Gilded Age craze for “Oriental” or Eastern art and design. Men wear straw hats and women stroll the street in white shirtwaists. It’s probably a warm day, and the brownstones on the right have their window shades down—the closest thing to air conditioning at the time.

The lone streetlight would have made this a much darker block than we’re used to today. Refuse cans (or are they ash barrels?) wait at the curb for pickup, perhaps by a White Wings street cleaning crew. Carts and wagons move through the street. If you needed to know the time, you would glance at the clock at the top of the building on the right at the corner of Fifth.

Looking past Fifth toward Sixth Avenue, trees can be seen on the north side of the street. That would be the Van Beuren Homestead, two circa-1830 brownstones surrounded by gardens and a patch of what was once farmland. (Imagine, a farm with a cow and chickens on the prime Gilded Age retail strip of Ladies Mile!)

Here, the lone survivor of the old New York family that built this homestead lived until 1908 while the urban city, with its 10-story limestone buildings and the Sixth Avenue Elevated, edged closer with each passing year.

[Top image: MCNY X2011.34.334]

August 16, 2021

A painter’s evocative look at an empty street beside the Manhattan Bridge

Anthony Springer was a lawyer-turned-artist who painted the energy and vitality of various downtown New York City neighborhoods until his death in 1995.

His work has been featured on this site before—rich, colorful images of quiet streets and empty stretches of Greenwich Village before the 1990s revitalization breathed new life into fading storefronts and forgotten corners…and in many cases changed the fabric of the neighborhood.

Here’s a Springer painting that offers a look at a slender street alongside the Manhattan Bridge. It calls up a time when you could find deserted streets like this downtown—populated by pigeons, a lone parked car (or stolen one ditched?), an industrial building not turned into lofts, a glorious bridge empty of the pedestrians and bikers seen today.

I’m not sure if we’re on the Manhattan or Brooklyn side, but it’s an evocative reminder of a different city.

Who is the rich New Yorker the Monopoly Man is based on?

At first glance, the board game Monopoly doesn’t seem like it has a New York City connection. The man who sold it to Parker Brothers in 1935 was from Philadelphia, and the board features properties in Atlantic City.

J.P. Morgan

J.P. MorganThen there’s that mustached man long dubbed “the Monopoly Man” or “Mr. Monopoly.” He appears on the Chance and Community Chest cards, always in a Depression-era suit with a bowtie and top hat.

But the Monopoly Man isn’t just a board game invention—this iconic character (who has an actual name, Rich Uncle Pennybags) is supposedly based on the image of an actual New Yorker.

Rich Uncle Pennybags

Rich Uncle PennybagsSo who is he? Apparently he’s modeled after banker J.P. Morgan. Morgan’s company financed some of the Gilded Age’s biggest corporations. He consolidated railroads, helped rescue the gold standard, and helped stabilize financial markets during the Panic of 1907, according to History.com. His former mansion on Madison Avenue is now the Morgan Library.

Phil Orbanes, a former VP at Parker Brothers and author of The Monopoly Companion, confirmed in this interview that the artist who drew Mr. Monopoly based him on J.P. Morgan.

Otto Kahn

Otto KahnOn the other hand, a site called monopolyland raises the possibility that Mr. Moneybags is based on Otto Khan, a German-born financier with a mansion on Fifth Avenue who died in 1934, close to the release date of Monopoly. (Morgan died in 1913.) Khan also wore a top hat and had the requisite mustache.

They both certainly look like Uncle Pennybags. A composite perhaps?

[Top image: Biography.com; second image: pixy.org; third image: Wikipedia]