Esther Crain's Blog, page 63

July 26, 2021

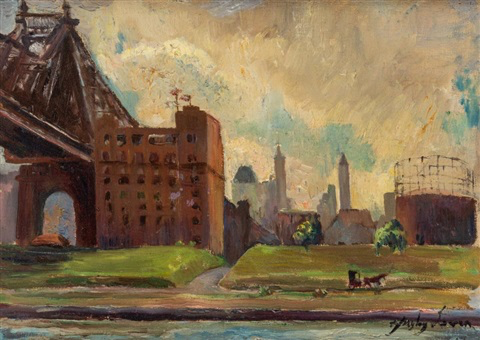

A painter in Astoria captures what he saw across the East River

When painters depict the East River, it’s usually from the Manhattan side: a steel bridge, choppy waters, and a Brooklyn or Queens waterfront either thick with factories or quaint and almost rural.

But when Richard Hayley Lever decided to paint the river in 1936, he did it from Astoria. What he captured in “Queensboro Bridge and New York From Astoria” (above) is a scene that on one hand comes across as quiet and serene—is that a horse and carriage in the foreground?—but with the business and industry of Manhattan looming behind.

This Impressionist artist gives us a view at about 60th Street; the bridge crosses at 59th, of course, and that gas tank sat at the foot of 61st Street through much of the 20th century.

Is the horse and carriage actually on Roosevelt Island or even still in Queens? Often these details can be found on museum and art or auction websites. Lever came to New York City from Australia in 1911 and taught at the Art Students League from 1919-1931, establishing a studio in the 1930s and teaching at other schools. But aside from this, I couldn’t find many details about his work.

He did paint the Queensboro Bridge and East River again though, as well as the High Bridge over the Harlem River and West 66th Street, among other New York locations. The title and date of the second image of the two ships is unknown right now. “Ship Under Brooklyn Bridge” (third image) is from 1958, the year he died after a life of artistic recognition and then financial difficulties, per this biography from Questroyal.

July 25, 2021

The 1916 stunt that made Nathan’s Famous a Coney Island hot dog icon

No summer visit to Coney Island is complete without a stop at Nathan’s Famous, the iconic boardwalk restaurant that offers everything from burgers to frog legs (really) but made its name back in 1916 selling delicious, cheap hot dogs.

Nathan’s Famous in the 1910s or 1920s

Nathan’s Famous in the 1910s or 1920sYet the five cent frankfurters Polish immigrant Nathan Handwerker began hawking from a stand on the then-unfinished boardwalk wouldn’t have caught on—if not for a clever stunt he came up with to convince the crowds on Surf Avenue to give his hot dogs a try.

Nathan’s in 1936, with a little competition by Nedick’s on the corner

Nathan’s in 1936, with a little competition by Nedick’s on the cornerThe story starts in the 1910s, when the reigning hot dog king at Coney Island was Charles Feltman, who ran a successful restaurant and beer garden and supposedly invented the hot dog (or hot dog bun, more precisely).

Handwerker worked for Feltman as a roll cutter and then a hot dog seller before deciding to go into business for himself with a friend, according to Nathan’s Famous: An Unauthorized View of America’s Favorite Frankfurter Company, co-authored by William Handwerker, Nathan’s grandson.

Nathan’s expanded its menu by 1939

Nathan’s expanded its menu by 1939 Feltman’s and other hot dog establishments sold their franks for 10 cents each. Handwerker priced his at the same rate, but he realized he wasn’t selling enough to make a profit. So he cut the price to a nickel.

Selling hot dogs for the cost of a subway ride sounds like a smart business move. But there was a lot of concern at the time that a hot dog so cheap couldn’t be made out of beef or pork but something a lot less appetizing, like horses, explained Larry McShane in a New York Daily News article marking Nathan’s centennial in 2016.

A Nathan’s customer in 1939

A Nathan’s customer in 1939Anticipating this concern on the part of the public, Handwerker came up with a genius idea: He’d hire men to wear white doctor coats and sit around his stand enjoying the cheap franks.

Handwerker “borrowed some doctor’s coats and stethoscopes from Coney Island Hospital personnel and put them on some men and had them eat franks in front of his stand,” wrote William Handwerker. “Potential customers said, ‘If it’s good enough for doctors, it has to be good enough for us.'”

Juicy hot dogs…and an amazing neon boardwalk sign!

Juicy hot dogs…and an amazing neon boardwalk sign!Sales increased, and Handwerker began attracting a devoted following. His little frankfurter stand (which didn’t even have a name for its first two years, according to William Handwerker) was on its way to becoming a Coney Island classic.

[Top photo: via New York Daily News; second photo: MCNY 43.131.5.13; third photo: MCNY 43.131.5.91; fourth photo: NYPL]

The noble mission of a Victorian Gothic building on ‘depraved’ Sullivan Street

When Charles Loring Brace founded the Children’s Aid Society in 1853, this 26-year-old minister came up with some radical ideas to help the thousands of poor and neglected kids who lived or worked on city streets—like sending children out West on so-called “orphan trains.”

But some of Brace’s ideas would seem like common sense to contemporary New Yorkers. Later in the Gilded Age, Brace decided to build lodging houses and “industrial schools” in New York’s impoverished neighborhoods, places where children could learn a trade and prepare for adult life.

In an era when options for street kids often meant the almshouse or an orphan asylum, homes and schools like these could be real lifelines.

Sullivan Street Industrial School in 1893

Sullivan Street Industrial School in 1893One of these industrial schools still stands on Sullivan Street between West Third and Bleecker Streets. Opened in 1892, it’s a red brick beauty with Gothic and Flemish touches (that stepped gable roof!) on a South Village block where Italian immigrants dominated in the late 19th century.

Brace ministered to street kids, but he also had famous friends. One was Calvert Vaux, the co-designer of Central Park as well as the creative genius behind the Jefferson Market Courthouse, just an elevated train stop away on Sixth Avenue and Ninth Street.

Sullivan Street, 1893, on the same block as the school

Sullivan Street, 1893, on the same block as the school“Brace enlisted his friend, architect Calvert Vaux, to undertake the designs of the Society’s dozen lodging houses, characterized by ornamental features that recalled Dutch architecture, meant to contrast with “ugly” surroundings that prevailed then,” wrote Brian J. Pape in WestView News.

Vaux designed the Sullivan Street school, as well as the Society’s Lodging House on Avenue B and Eighth Street, the Elizabeth Home for Girls on East 12th Street, and the Fourteenth Ward Industrial School on Mott Street, all of which are still part of the cityscape and share the same architectural flourishes.

Sullivan Street, 1895

Sullivan Street, 1895To fund the school, two benefactors stepped forward with the $90,000 needed: Mrs. Joseph M. White and Miss M.W. Bruce, according to an 1892 New York Times article. Supporting the Society was popular with wealthy Gilded Age families, and both women had long been involved in the Society’s efforts.

Opening day in December was captured in print. “The children, to the number of 420, girls and boys, between the ages of five and thirteen, were marshaled into the audience room under the charge of Mrs. C. Forman, principal of the school, and her nine assistant teachers,” wrote the New York Times. “They were dressed in their new suits of clothing, given to them on Monday last by Miss Bruce.”

The school and a next-door playground in 1939-1941

The school and a next-door playground in 1939-1941For decades, the Sullivan Street Industrial School served a community that became one of Manhattan’s Little Italy neighborhoods. Classes in woodworking, metalworking, sewing, dressmaking, cooking, and other skills were offered.

The Society didn’t beat around the bush about the rough and tumble neighborhood, however. “This school was placed in one of the most depraved localities in the city and already an improvement in the neighborhood is visible,” the Society wrote in a 1892 report.

The school was more than just a place of learning. An 1899 report by Principal Forman explains that funds were raised from “generous friends” to distribute food and fuel, as well as hot dinners. An organization called the Odds and Ends Society “furnished many warm and comfortable garments” for the children, and mothers who were considered “deserving poor” with husbands out of work were given money to help with rent.

Today, it looks like this former lifeline is a rental building on a much more affluent Sullivan Street. At least one apartment offers up-close views of that stepped gable roofline.

[Second image: History of Child Saving in the United States; third and fourth images: NYPL; fifth image: NYC Department of Records and Information Services]

July 19, 2021

A tenement sign high up at the corner of First Street and First Avenue

The corner of First Street and First Avenue is roughly the borderline of the East Village. And what better than an old-school address sign like this one affixed to a handsome brick building to welcome you to the neighborhood as you leave the Lower East Side behind?

These early 20th century address markers can be found on many tenement corners throughout New York City. In some cases, they may have served to let elevated train riders know exactly where they were passing.

Or perhaps these signs—sometimes raised and embossed, other times carved into the building—simply let pedestrians know where they stood in an era when reliable street signs had not yet arrived to ever corner in poor neighborhoods.

Beat writers and bohemians: One woman’s memoir of 1950s Greenwich Village

“When I got back to New York after my divorce came through there was never any question that Greenwich Village was where I wanted to be,” recalled Helen Weaver in her 2009 autobiography, The Awakener: A Memoir of Kerouac and the Fifties.

Helen Weaver and Jack Kerouac, undated

Helen Weaver and Jack Kerouac, undatedIt was 1955 and Weaver was in her early 20s. Her brief marriage to her college boyfriend was behind her, and she looked forward to moving to a “patchwork crazy quilt” section of Manhattan filled with “artists, would-be artists, and oddballs like myself.”

“To the overprotected little girl from Scarsdale that I was, the very dirt of the streets and the subway and the stairs of tenements was exciting,” she wrote. “It represented freedom from everything I had escaped: parents, marriage, academia.”

Sullivan Street and West Third, 1950s

Sullivan Street and West Third, 1950sLittle did Weaver know that she’d find herself part of the fabric of bohemian Village life in the 1950s and early 1960s: a love affair with Jack Kerouac, dalliances with poet Gregory Corso and Lenny Bruce, and a witness to the Village’s transformation from quirky and artsy to a neighborhood with rougher edges.

He story at first sounds like that of any young adult who arrives in the Village on their own. First, Weaver had to get an apartment: a third-floor walkup on Sullivan Street.

“E.B. White wrote that New York City ‘bestows the gift of privacy, the jewel of loneliness,’: she wrote. “That first apartment was a magical place for me because it was there that I learned the art—and the joy—of solitude.” To pay for her space, she secured a position as a “gal Friday” at a publishing house.

Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Gregory Corso

Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Gregory CorsoA college friend also on Sullivan Street showed her how to live, getting furniture at the Salvation Army, dressing like a Village bohemian (“long skirts, Capezio ballet shoes, and black stockings”), and going to dinner at the Grand Ticino on Thompson Street. They also visited Bagatelle, a lesbian bar on University Place.

A new friend—Helen Elliott, a free spirit who had attended Barnard—became her roommate in her next apartment at 307 West 11th Street, “an old brownstone with a small paved courtyard just west of Hudson Street and kitty-corner from the White Horse Tavern of Dylan Thomas fame.”

So thrilled to have a bigger apartment, it wasn’t until after she moved in that Weaver realized there was no kitchen sink. No matter, they would do the dishes in the bathtub.

White Horse Tavern in 1961, across from Helen Weaver’s West 11th Street apartment

White Horse Tavern in 1961, across from Helen Weaver’s West 11th Street apartmentHelen Elliott had become friendly with Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac while at Barnard, and one November morning in 1956 the two not-yet-famous Beat writers showed up at Weaver and Elliott’s apartment. They had just returned to New York after hitchhiking from Mexico.

Elliott and Ginsberg went off to see fellow Beat Lucien Carr, who lived on Grove Street. Back on West 11th Street, Weaver and Kerouac began their tumultuous year-long relationship, which was marked by Kerouac’s drinking, long absences, and then the 1957 publication of On the Road, which made him a celebrity.

Upset that Kerouac wasn’t the man she wanted him to be, Weaver had a one-night stand with poet Gregory Corso before breaking things off for good.

Villagers at Cafe Wha?

Villagers at Cafe Wha? “The pain of my disappointment in Jack and the pain of rejecting him was compounded by the pain of rejecting the part of myself that felt most alive,” wrote Weaver.

As the 1950s slid into the early 1960s, Weaver moved to a third apartment on West 13th Street. She smoked her first joint with a boyfriend and began campaigning for the legalization of marijuana.

She also became a fan of rising comic Lenny Bruce, attending his show at the Village Theater on Second Avenue (later it would become the Fillmore East) eight days after John F. Kennedy was assassinated.

In 1964, when Bruce was arrested for obscenity at the Village’s Cafe Au Go Go, Elliott and Weaver started a petition in support of Bruce’s right to free speech. When Bruce heard about it, he got Weaver’s number and thanked her…then came to her apartment, where the two went to bed together.

“All those hours Helen and I had spent listening to his voice on the records: that was our foreplay. And his gig at the Village Theater back in November: that was our first date,” Weaver wrote. In the end, Bruce was convicted of obscenity. (Bruce died two years later of a heroin overdose before his appeal was decided.)

In the 1960s, Weaver moved a final time to West 10th Street. But rising crime drove her to leave the neighborhood she loved.

MacDougal Street, 1963

MacDougal Street, 1963When she first came to the Village, she recalled being able to walk around at any hour of the night and feel safe. Not so anymore: “Near Sheridan Square I saw a big bloodstain on the sidewalk. Another time in the subway a man punched me in the breast. I started taking cabs home instead of riding the subway. It got so I was afraid to walk to the corner deli after dark for a quart of milk. New York was getting scary.”

In 1971, she sublet her apartment and relocated to Woodstock, where she worked as a translator and astrology writer. Except for short trips back to New York City to see old friends and be part of Beat Generation events, Weaver never lived in the city again.

Helen Weaver in the 1950s

Helen Weaver in the 1950sShe began her memoir in the 1990s. By the time it was published in 2009, the main characters—Helen Elliott, Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Gregory Corso—had all passed away. Weaver died in April of this year at 89. She was perhaps the last of a group whose sense of adventure and artistic leanings defined a certain time and feel in Greenwich Village.

[Top photo: from The Awakener: a Memoir of Kerouac and the Fifties; second image: oldnycphotos.com; third image: unknown; fourth image: LOC; fifth image: NYPL; sixth image: Village Preservation; seventh image: Robert Otter; eighth image: The Awakener: a Memoir of Kerouac and the Fifties]

July 18, 2021

This pricey co-op building was once a Lower East Side public library

New York developers have made apartment buildings out of former hospitals, police stations, schools, and churches. Now, a library branch has undergone the transformation to luxury housing.

What was once the Rivington Street branch of the New York Public Library has been rebranded as a Lower East Side boutique co-op called, of course, “The Library.”

Purchased by a developer in 2018 and renovated into 11 high-end units, The Library is already luring buyers, even though it doesn’t look like the co-op redo transformation is finished. But it’s not much of a surprise that many of the units have been snapped up, considering the recent reinvention of the Lower East Side as a posh area.

Imagine Rivington Street the way it was in the early 1900s as part of a very different Lower East Side.

Opened in 1906 on a crowded block between Eldridge and Allen Streets, the Rivington branch was designed by McKim, Mead, & White in the popular Beaux-Arts style. The architectural firm was responsible for great public buildings like Penn Station, but they also took on smaller projects, such as the Tompkins Square NYPL branch on East 10th Street.

The Beaux-Arts design lent a sense of elegance to a building largely patronized by poor immigrants living in the neighborhood’s surrounding shoddy tenements.

Engaged readers on the roof

Engaged readers on the roofThe Rivington branch was one of the city’s new “Carnegie” libraries, funded by wealthy industrialist Andrew Carnegie (who lived in a more than 100 blocks north). The main New York Public Library building was still under construction on 42nd Street and Fifth Avenue, set to open in 1911.

Like other neighborhood libraries, the Rivington Street branch quickly had a devoted following. Part of its popularity might be due to the open-air reading area on the roof, which proved to be a huge draw during the hot summer months, according to a 1910 New York Times article.

As the photo above shows, the roof really was for dedicated reading rather than sunbathing or goofing off. “Only children or adults actually engaged in reading are permitted to stay,” the Times wrote.

So how did the library branch end up as a co-op? I’m not sure when the branch was decommissioned as a library, but at that point a church took the building over. A developer bought it from the church in May 2018, renovating the former reading rooms and adding three stories.

The “adult desk” at the Rivington Street NYPL branch

The “adult desk” at the Rivington Street NYPL branchWhat does it cost to live in a former library, where generations of New Yorkers read, dreamed, educated themselves, and stole some time away?

It’s not cheap. The five-room penthouse is in contract for more than $4 million, according to Streeteasy. At least the engraved plaque on the front that reads “New York Public Library” is still on the facade, a reminder of the building’s original purpose.

[Second photo: NYPL. Third photo: New-York Tribune, 1906. Fifth photo: NYPL]

July 12, 2021

A painter captures the last years of these East Village tenements

A New Yorker since his birth in 1928, Arthur Morris Cohen studied at Cooper Union from 1848 to 1950, according to askart.com. So he knew the neighborhood when he decided to paint what looks like the southeast or southwest tenement corner at Third Avenue and 9th Street in 1961.

Cohen’s version of the corner would be similar to what it probably actually looked like in the early 1960s. The East Village was not even the East Village yet; it would be a few years before the tenement neighborhood was rebranded from the Lower East Side, which was on the decline economically.

1941 tax photo of 111-113 East Ninth Street

1941 tax photo of 111-113 East Ninth StreetNone of these walkups exist today. In fact, all four corners at Third and Ninth are occupied by postwar buildings. On the southwest corner is a 1960s-era white brick apartment building called the St. Mark, which likely took the place of these low rises in 1965, when the building was completed. Or maybe the row stood where a huge NYU dorm has been since the 1980s, with Stuyvesant Place running alongside it.

This 1941 tax photo from the NYC Department of Records and Information Services at the southwest corner gives some idea of what Cohen painted.

July 11, 2021

The Central Park spring that provided water for a forgotten village

It looks more like a large puddle than a source of fresh water. But close to Central Park West and about 82nd Street at Summit Rock is something unusual: one of the few remaining natural springs in Central Park.

Tanner’s Spring, 2021

Tanner’s Spring, 2021It’s called Tanner’s Spring, and there’s a story behind that name. In the summer of 1880, Dr. Henry Samuel Tanner became the most famous man in the U.S. when he launched a 40-day fast, abstaining from all food and drink except for the “pure” water from this spring—which then became a local attraction associated with health and wellness.

But Tanner’s Spring has an earlier 19th century distinction: It may have been the water source that allowed Seneca Village to flourish, according to the Central Park Conservatory.

What was called “Dr. Tanner’s Well” in the caption looked different in 1899 in this NYPL Digital Collection image

What was called “Dr. Tanner’s Well” in the caption looked different in 1899 in this NYPL Digital Collection imageSeneca Village has been described as a small community of roughly 300 people in this rocky, hilly section of Manhattan between 82nd and 89th Streets and Seventh and Eighth Avenues, stated educational material from the New-York Historical Society.

From the 1820s to the 1850s, Seneca Village was a mostly African American enclave also home to Irish and German immigrants. Three churches, a school, cemeteries, and small houses with gardens made this outpost a true village similar to the many villages dotting uptown Manhattan in the mid-19th century, albeit a small one.

Not identified as Seneca Village, but an idea of what the community may have looked like, from the NYPL

Not identified as Seneca Village, but an idea of what the community may have looked like, from the NYPL“Historians speculate that Black New Yorkers living downtown began moving to Seneca Village in part to escape the racist climate and unhealthy conditions of Lower Manhattan,” wrote the Central Park Conservatory. Here, Black residents, who likely worked in the service trades, were also property owners.

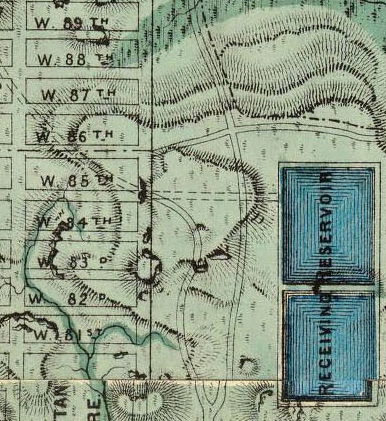

In pre-Croton New York, the many streams across Manhattan were vital, and Seneca Village wouldn’t have thrived without this one. Even after the Croton Aqueduct opened in 1842, water from the nearby Receiving Reservoir wasn’t accessible; it was piped to the Distributing Reservoir on 42nd Street and then to downtown homes and businesses.

Egbert L. Viele’s 1865 “Sanitary and Topographical” map shows the spring where Seneca Village once stood.

Egbert L. Viele’s 1865 “Sanitary and Topographical” map shows the spring where Seneca Village once stood.Much is still unknown about Seneca Village—but its demise is no mystery.

When city officials decided to build New York’s great park here, they seized the land via eminent domain in the mid-1850s and kicked out everyone living within the boundaries of the yet-to-be-built park, including residents of Seneca Village. Roughly 1,600 people were forced out, and at least some land owners were paid by the city.

The spring is behind a short wire fence

The spring is behind a short wire fenceForgotten for more than a century, Seneca Village is the subject of renewed interest. Historians have discovered stone foundation walls and thousands of artifacts, including the handle of a pitcher that one can imagine held fresh, cool drinking water from nearby Tanner’s Spring.

July 5, 2021

‘Inertia and desolation’ of Sunday in New York in the 1920s

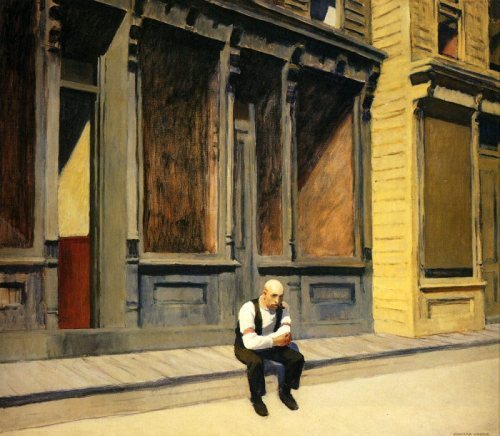

Like so many paintings by Edward Hopper, “Sunday,” completed in 1926, is shrouded in mystery. Who is this lone man sitting on the curb, and what’s the significance of the row of empty storefronts he’s turned his back on?

The scene may be ambiguous, but the sense of isolation and disconnection conjured by the image will feel familiar for New Yorkers in the 1920s and the 2020s as well.

“Sunday depicts a spare street scene,” explains the Phillips Collection, which owns the painting. “In the foreground, a solitary, middle-aged man sits on a sunlit curb, smoking a cigar. Behind him is a row of old wooden buildings, their darkened and shaded windows suggesting stores, perhaps closed for the weekend or permanently.”

Though it’s impossible to know, this scene might be in Greenwich Village, near where Hopper lived and painted for most of his life on the Washington Square North.

“Oblivious to the viewer’s gaze, the man seems remote and passive,” the Phillips Collection continues. “His relationship to the nearby buildings is uncertain. Who is he? Is he waiting for the stores to open? When will that occur? Sunlight plays across the forms, but curiously, it lacks warmth. Devoid of energy and drama, Sunday is ambiguous in its story but potent in its impression of inertia and desolation.”

“Sunday” shouldn’t be confused with “Early Sunday Morning,” a better-known Hopper painting of a row of two-story buildings thought to be on Bleecker Street. That painting has a similar haunting, solitary feel. The same unbroken line of low-rises he depicts still exist today.

Beautiful ruins of the early 1900s “Bankers’ Row” on West 56th Street

When an area in Manhattan becomes fashionable—as Fifth Avenue in the upper 50s did in the 1880s and 1890s—only people with the most elite names (think Vanderbilt, Vanderbilt, and Vanderbilt) are typically able to acquire property and build their mansions there.

The gaping hole between 17 and 23 West 56th Street

The gaping hole between 17 and 23 West 56th StreetBut Gilded Age New York was minting many social-climbing millionaires. So the side streets off Fifth Avenue filled up with beautiful, costly, single-family townhouses designed by top architects. In many cases, these architects gave opulent facelifts and redesigns to preexisting modest brownstones, which were now out of style.

One block in particular, 56th Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues, became home to so many financiers and their families, it earned the nickname “Bankers’ Row” after the turn of the century.

30 West 56th Street, former home of investment banker Henry Seligman

30 West 56th Street, former home of investment banker Henry SeligmanAnd while it’s hard to imagine this block with some notably shabby exteriors and empty lots as a wealthy New Yorker’s enclave, enough of the old dowager beauties with illustrious backstories remain to prove you wrong.

One of these is Number 30 (second from left, above, and below), designed by C.P.W. Gilbert and completed in 1901 for investment banker Henry Seligman and his wife, according to the Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC).

“Henry and Adelaide had three children, Gladys, Rhoda and Walter,” states the LPC. “The lavish townhouse at 30 West 56th Street also housed a Scottish butler; an American valet and chauffeur; a Swedish footman, maid and laundress; two Irish cooks; and three English, Swedish, and French servants.”

The couple lived in the house until their deaths in 1933 (the year Henry died of a heart attack inside) and 1934; it was converted into apartments in 1941, per the LPC.

26 West 56th Street, once home of E. Hayward and Amelia Parsons Ferry

26 West 56th Street, once home of E. Hayward and Amelia Parsons FerryNumber 26, currently behind scaffolding, sits two doors down from the Seligman mansion (above, center). Built in 1871, it was remodeled in 1907-1908 with a limestone facade and copper roof and “long occupied by banker E. Hayward Ferry and his wife Amelia Parsons Ferry,” according to w50s.com.

“E. Hayward Ferry was a prominent businessman who served as first vice president of Hanover Bank from 1910 to 1929,” w50s.com states. “He and his wife occupied this house from 1908 to 1935.”

28 West 56th, in the Arts & Crafts style

28 West 56th, in the Arts & Crafts styleDr. Clifton Edgar is one resident of Bankers’ Row who wasn’t actually a banker. A prominent physician, Edgar had 28 West 56th Street redesigned in 1908 from its original brownstone style to an Arts and Crafts townhouse (above)—one of few examples of this architectural style in Manhattan, states Community Board 5.

Widow Edith Andrews Logan acquired her wealth from her industrialist father and horsebreeder husband, who was killed in the Spanish-American War. In 1903, she bought 17 West 56th Street and had it redesigned in the neo-Federal style, with fluted columns and Flemish bond brickwork, per the LPC.

Mrs. Logan’s townhouse, where her daughter made her society debut

Mrs. Logan’s townhouse, where her daughter made her society debutLogan made good use of her stylish home: She held an “informal dinner dance” that served as the debut of one of her daughters into New York society in 1909. The next year, she hosted that daughter’s wedding reception. Long after Logan departed her house, Number 17 became a trendy restaurant called the Royal Box in the 1930s.

These days, what was once Bankers’ Row is now more of a Restaurant Row. Many of the wealthy palaces of the early 1900s have long since been converted into ground-floor restaurants and chopped into apartments.

Some original modest brownstones, others lavish townhouses

Some original modest brownstones, others lavish townhousesOthers have been demolished entirely; the block has missing buildings and lots of signs of redevelopment. But beneath the restaurant signs, grime, and scaffolding, some of the former showstoppers of Bankers’ Row are still hanging on.

[Fourth image: Google]