Esther Crain's Blog, page 66

May 16, 2021

The two most romantic street names in old Manhattan

New York has always been a city that encourages love and passion, with plenty of lush parks, quiet corners, and candlelit cafes lending privacy and romantic ambiance.

Couples living in 18th and early 19th century Manhattan didn’t have these places at their disposal when they wanted some alone time, of course. But they did have options—like the two now-defunct streets named “Love Lane.”

The first Love Lane began at the foot of the Bowery, called Bowry Lane on John Montresor’s 1775 map (above, and in full via this link). This map laid out the small city center at the tip of Manhattan and along the East River.

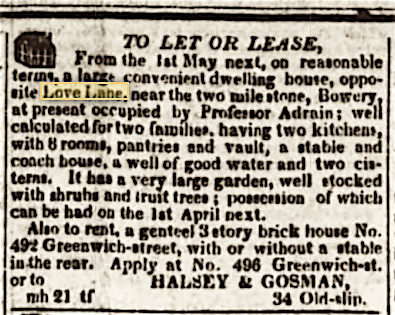

Love Lane off the Bowery (referenced in an 1818 New-York Evening Post ad, above) was a “road on the Rutgers Farm, running on or near the line of the present Henry Street,” states oldstreets.com, a site that explains the history of city street names.

Thomas Allibone Janvier’s In Old New York, published in 1893, mentions this “primitive” Love Lane, which he also places on the former Rutgers Estate near present-day Chatham Square. Valentine’s Manual of Old New York, from 1922, states that Love Lane was the original name for today’s East Broadway; it was a lane that led to the Rutgers Farm.

Exactly what colonial-era New Yorkers did on the Love Lane of the Rutgers Estate wasn’t specifically recorded by these authors. But we do have a better idea of what lovers (or would-be lovers) did on the city’s other Love Lane—which ran along West 21st Street in today’s Chelsea. Apparently, they went for long, secluded carriage drives.

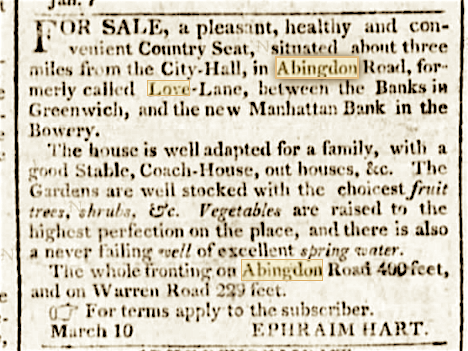

“Before this area became incorporated into an expanding New York City, 21st Street was a rural lane known as the Abingdon Road, which connected Broadway with Fitzroy Road, as 8th Avenue was then called,” explains nysonglines.com.

“Abingdon was nicknamed Love Lane, because carriage rides out to the country (i.e. Midtown) were apparently the main form of dating, and coming back by Abingdon was taking the long way home.”

Different sources have Chelsea’s Love Lane taking various routes. But it seems to have begun at Broadway (then called Bloomingdale Road) and followed 21st Street west before intersecting with Fitz Roy Road, following today’s 22nd to 23rd Street, and running to Tenth Avenue beside the Hudson River.

“There is no record to show where the name came from,” wrote Charles Hemstreet in Nooks and Corners of Old New York. “The generally accepted idea is that being a quiet and little traveled spot, it was looked upon as a lane where happy couples might drive, far from the city, and amid green fields and stately trees confide the story of their loves.”

Valentine’s Manual agrees that this Love Lane followed Abington Road up the West Side to Fitz Roy and 21st Street, but has it turning east to Third Avenue and 23rd Street.

Chelsea’s Love Lane (above, in an 1807 map by William Bridges and Peter Maverick) was “swallowed up,” Hemstreet wrote in 1899, with the opening of West 21st Street in 1827.

Both of these Love Lanes have long disappeared from the urbanscape. But if you’re wishing you could live on a street with such a romantic name, head on over to Brooklyn.

Love Lane, a sweet one-block former mews in Brooklyn Heights, is quiet, tucked out of the way, and intimate. How this street got its name is something of a mystery, which the Brooklyn Daily Eagle explores in a 2019 article. It may have been a romantic path down to the East River; it could have something to do with the women’s college once located around the corner.

[Top image: Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps; second image: New-York Evening Post; third image: unknown; fourth image: New-York Evening Post; fifth Image: NYPL]

May 9, 2021

‘Little Hungary’ was once on East 79th Street

A few weeks ago, Ephemeral New York put together a post about the former Czech neighborhood once centered around 72nd Street between First and Second Avenues on the Upper East Side.

The post generated many comments, with readers either reminiscing about a vanished enclave they remember well or wishing Manhattan still had pockets of ethnic neighborhoods like that one.

This week while looking through some photo archives, I find these images of a Hungarian grocery store. It could have been taken in Budapest, perhaps, but it’s actually Second Avenue between 78th and 79th Streets—smack in the middle of an area that used to be New York’s Little Hungary.

Like the old Czech neighborhood, Little Hungary had its churches and schools, community centers, and shops selling groceries and delicacies, like this one above. It isn’t the city’s first Hungarian neighborhood; that was on Second Avenue in the East Village. But at the turn of the century, just like their German and Czech neighbors, Hungarian immigrants relocated and colonized Yorkville through much of the 20th century.

Use Google Translate to find out all the unique offerings one could pick up here, foods I doubt you’ll be able to find on East 79th Street today.

[Top photo: NYPL; second photo: NYC Department of Records and Information Services]

Solving the mystery of a Brooklyn cafeteria ghost sign

Downtown Brooklyn’s Fulton Street has been a bustling shopping destination since the 19th century. Storefronts have changed hands many times, and signs have gone up and down over the years as the street went from Gilded Age posh to middle class to more of a discount area through the decades.

But there’s something unusual above a storefront at the corner of Fulton and Jay Streets. Look up, and you’ll see a sliver of a ghost sign between an Ann Taylor and a human hair wig shop.

What’s left of the sign at 447 Fulton Street says “teria,” for cafeteria. The cafeteria logo, an apple with a W on it, is visible as well. What was this cafeteria, and when did it serve hungry Brooklyn shoppers?

It’s a mystery solved by the New York City Department of Records and Information Services. A quick search through their 1940 tax photo archive shows that it was a Waldorf Cafeteria, which appears to have two entrances at this corner: one on Fulton Street (harder to see on the photo’s right side) and one on Jay Street (at left).

Old-time New Yorkers might remember the Waldorf Cafeteria chain. Founded in 1903 in Massachusetts, franchises opened in New York City as early as the 1930s and seemed to stick around until at least the 1950s in various locations in Brooklyn, Manhattan, and the Bronx.

The life span of the Waldorf Cafeteria on Fulton Street is unclear. But it might have been in business since the early 1930s, if this is it in a 1931 photo from the Museum of the City of New York that didn’t have a location listed in the description.

The cafeteria was certainly there in the 1940s, as the tax photo shows, and as the dozens of help wanted ads in 1940s New York City papers reveal. This ad comes from the Brooklyn Eagle on May 8. 1944. Women and girls were in demand, with so many young men away at war.

The Waldorf Cafeteria chain also figures into the backstory of a writer’s sordid death in the 1950s. Poet, gadfly, and Greenwich Village character Maxwell Bodenheim met with a literary agent at a Waldorf on Park Avenue and 25th Street the day before he was found murdered in a Third Avenue flophouse in 1954.

The Waldorf remnant sign on Fulton Street looks like it could date to the 1950s or 1960s, though photos from those decades don’t seem to be available. Whenever it dates to, big thanks to Ephemeral reader Joe Mobilia for noticing the sign and snapping the photos.

[First and second photos: Joe Mobilia; third photo: NYC Department of Records and Information Services; fourth photo: MCNY X2010.7.1.16877; fifth image: Brooklyn Eagle.]

The Chelsea ‘Muffin House’ where a beloved brand was baked

In the 1830s, Clement Clarke Moore began selling off parcels of land from his country estate, a retreat north of Greenwich Village that his grandfather had named Chelsea in the 18th century.

Moore—a wealthy professor best known as the author behind ‘Twas the Night Before Christmas—planned to develop his estate into a fine residential neighborhood for elite members of the growing city, according to the Chelsea Historic District report.

Unfortunately, the new Chelsea neighborhood didn’t last as an enclave of huge brownstones and mansions. Instead, it became a “comfortable and middle class” district through much of the 19th century, per the CHD report.

By the end of the 19th century, the exclusively residential neighborhood Moore had planned gave way to commercial enterprises—including one iconic bakery brand that introduced New York to the English muffin and is still sold across the US today.

That brand was Thomas’ English Muffins, which were baked in the basement of the circa-1850 brick house on 20th Street between Eighth and Ninth Avenues (photos above).

The Thomas’ English muffin story begins in 1874, when baker Samuel Bath Thomas (above) left England and settled in New York City, determined to bring his family’s English muffin recipe (these muffins were originally called “toaster crumpets,” reports The Nibble) to the American masses.

He opened his first bakery in 1880 at 163 Ninth Avenue, according to a 2006 New York Times article. Business was good. So in the early 20th century, Thomas opened another bakery around the corner in the basement and ground floor of 337 East 20th Street, a three-story dwelling with a hidden back house on the property.

“Sam’s muffins were sold on the streets of New York by those basket-carrying, bell-ringing muffin men of song and story, by Sam in the retail store—upstairs from the bakery and downstairs from his apartment—and by pushcarts to restaurants in the neighborhood,” states a New York Daily News article from 1980, commemorating the 100th anniversary of the English muffin’s introduction to the United States.

“Finally, as the fame of Thomas’ muffins spread to the suburbs, which were then places like Queens and Brooklyn, Sam bought a horse and wagon to haul around all the muffins he was making,” the Daily News wrote. (See the above photo, with the 20th Street store address on the side of the wagon.)

Thomas died in 1918 just as a new English muffin plant was going up in Long Island City. The business carried on with the help of relatives before being sold to a manufacturer, which still produces them today.

But what of the former bakery at 337 West 20th Street? It’s unclear when it was abandoned; the ground floor was still used as a storefront in the tax photo from 1940. But amazingly, the enormous oven in which Thomas’ muffins achieved their nook and cranny goodness was found in 2006 behind a basement wall.

Tenants of the apartment on the other side of the wall made the discovery of the “room-size brick oven,” as the Times described it. The nonworking oven—likely originally built for the foundry that used to be in the basement before being converted to bakery use—was built into the basement foundation, and most of it stretches underneath the courtyard between the main building and the back house (below).

Number 337 is now a co-op apartment residence. On the facade of the building is a charming sign giving some historical background on what’s now affectionately known as the “muffin house.”

[Third and fourth photos: Thomasbreads.com; fifth photo: NYC Department of Records and Information Services; seventh photo: Streeteasy.com]

May 2, 2021

The “romantic reality” of midcentury Village street scenes

Can you feel it? Right now, New York has a vitality that went into a dark sleep in early 2020. People are out on the sidewalks performing the rituals of urban living; the city is emerging dynamic and alive.

What New Yorkers are feeling this spring is hard to describe—but Alfred Mira captures it perfectly in his paintings. Born in Italy in 1900, Mira made his home in Greenwich Village and supported himself as an artist.

His seemingly ordinary street scenes—like this two above of Seventh Avenue South and then a rainy Greenwich Avenue in the 1940s, or below of Washington Square Park in 1930—pulse with New York’s unique excitement and passion.

Mira’s paintings “have a rare skill in suggesting, rather than slavishly and verbosely saying,” wrote one critic reviewing an exhibit of Mira’s work in 1943 Los Angeles. “That accounts for the vibrant movement of his street scenes. The people, the buildings, the buses and passenger cars and other items in his paintings appear more real than the things themselves. They have what in fiction has been called ‘romantic reality.'”

The 6 Civil War-era survivors of East 78th Street

There’s beauty in symmetry, so on a walk uptown I had to stop and admire the striking row of six Civil War–era brick houses at 208-218 East 78th Street, between Second and Third Avenues.

These remnants—the survivors of an original row of 15 houses—are more than eye-catching; they’re rather unusual for their era. The elliptical windows and doorways set them apart from their rowhouse neighbors. And at a little over 13 feet across, each is more slender than most brick and brownstone houses.

There has to be a story behind them, and it starts with the opening of the Third Avenue railroad in 1852. At the time, the area was part of the Village of Yorkville. New York existed mostly below 23rd Street; few streets above 42nd Street were even graded.

But thanks to the new railroad and regular horsecar service running up and down the East Side, people living in the upper reaches of Manhattan were within commuting distance to the city center. That made land on the Upper East Side very appealing to developers.

In 1861, a speculative developer named Howard A. Martin purchased 200 feet of property deemed “common grounds” and owned by the city on the south side of the block. He also paid for the right (in the form of a fine) to have East 78th Street officially opened, according to a Landmarks Preservation Commission report.

Martin was the one who subdivided the land into 15 separate 13-foot lots (probably because the smaller the lot, the more houses could be squeezed in). He in turn sold the lots to another speculator, William H. Brower, in 1862.

“Because each of the 15 lots was the same width and the same builders were responsible for the construction of all, the 15 houses in the row were probably identical in appearance even though Brower sold all of the properties to several different owners before construction was completed in 1865,” the LPC report states.

Building these modest beauties in the fashionable Italianate style took longer than usual because of the Civil War, which made materials (and perhaps men to do the work) harder to find.

The first owners of the 15 houses were a varied group of well-off but not rich New Yorkers: a dry goods businessman, a man in the varnish business, another man who worked in bags and satchels, and a widow. Some of these owners quickly resold their home. With the city expanding in the Gilded Age and the Upper East Side becoming a desirable area, they likely made a nice profit.

Over the next century and a half, owners came and went; nine of the houses were lost to the bulldozer. But amazingly, the remainders have barely been altered. Ironwork has been replaced, as have front doors. (Above, number 210 in 1940)

But the cornices remain, uniting the houses at the roofline. (Mostly; number 218’s cornice seems uneven.) And those oval doors and windows mark them as unique.

They aren’t the oldest rowhouses in the neighborhood; that honor has been given to these houses down the street at 157-165 East 78th, which were completed in 1861. Yet they might be the most charming.

[Third image: NYC Records and Information Services Tax Photo]

April 26, 2021

A 1908 fountain where Central Park horses can drink

It’s not Central Park’s most ornate horse water fountain. That honor likely goes to the Victorian-era Cherry Hill fountain, which to my knowledge no longer works but is quite beautiful, with frosted glass lamps and black goblets.

But the bathtub-shaped granite trough at the Sixth Avenue entrance to Central Park also contains a fountain—bringing fresh water to the animals that Henry Bergh, founder of the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals in 1866, dubbed the “mute servants of mankind.”

The fountain was donated to the ASPCA by a Mrs. Henry C. Russell in 1908. Where the fountain was originally installed isn’t clear, but in 1983 it was found at Kennedy Airport’s “animal shelter,” according to a 1988 New York Daily News article, and then brought to City Hall Park.

After a Central Park carriage horse “swooned” in the summer heat in 1988, an outcry prompted the city to move Mrs. Russell’s fountain—now 113 years old—to this spot beside the park, near a line of waiting horses and their drivers.

April 25, 2021

What remains on a Hell’s Kitchen block from an 1883 painting

Louis Maurer immigrated to New York from Germany in 1851 when he was 19 years old (second image below). He first worked as a cabinetmaker in the antebellum city—but within a few years he became a painter and lithographer working for Currier & Ives and then his own lithography firm from an office on William Street.

As an artist, his subjects ranged from firefighters to racehorses. But in 1883 he painted what might be one of his few urban landscapes, “View of Forty-Third Street West of Ninth Avenue.”

Maurer didn’t have to go far to paint this Manhattan street scene. His longtime home where he lived with his wife and children (including Modernist painter Alfred Maurer) was at 404 West 43rd Street, according to his New York Times obituary from 1932. (You can see what were probably his front steps with cast iron handrails on the far right of the painting.)

Maurer would only have to look out his parlor window to capture the action: children playing in the Belgian block street, adults in the background going about their day on the sidewalk, and the man whose job it was to empty ash barrels pouring the contents of one into his horse-drawn wagon (while a black scaredy cat runs off).

What’s special about the painting is how ordinary it is—depicting what was likely an average unglamorous city block, with red brick tenements on three corners, horses and carriages traversing the streets, and the steam train sending belching smoke along Ninth Avenue.

What else is unique about this piece of visual poetry? The corner doesn’t look entirely unrecognizable now, 138 years later. (Or even a half-century later in the above photo of the same block in the 1930s.)

Sure, the Belgian blocks are now asphalt; the ash barrels have been replaced by garbage and recycling bins. It’s been decades since kids played in New York City streets, and parked cars have replaced a waiting horse and wagon. The Ninth Avenue El met its bitter end in 1940. Times Square, just a few avenues away, was sparsely settled Longacre Square, at the time the center of New York’s carriage trade.

But see the tenement building with the side entrance on the northwest corner—today it looks almost identical. And across Ninth Avenue on the northeast corner is another red-brick building looking strangely similar to the one in Maurer’s painting.

[Second Image: Wikipedia; third image: NYPL]

Look hard to see this vintage Hershey’s sign on the Bowery

You might need a pair of readers to really see the Hershey’s brand name in this weathered sign hanging from the facade of 354 Bowery, between East Third and Fourth Streets.

But there it is embossed on both sides, advertising Hershey’s Ice Cream—which despite the similar lettering apparently has nothing to do with Hershey’s Chocolate.

How long has the sign been there? No earlier than 1940, as it doesn’t appear in the tax photo from that year archived by the New York City Department of Records and Information Services. This stretch of the Bowery back then was all hardware stores, sign makers, and a low-rent hotel called the Gotham.

However old it is, this it’s a charming relic of a time when the Bowery made room for a deli or luncheonette with ice cream on the menu. It might qualify as a “privilege” sign—a store sign featuring a brand’s name and logo, and typically the name of the store. The store owners didn’t have to pay for the sign because it was free advertising for the brand.

To see a clearer image of the sign, visit the Facebook group Ghost Signs—this snap was taken by Tori Terazzi back in January.

April 19, 2021

5 remnants of the old Czech neighborhood on the Upper East Side

It’s been decades since Czech could routinely be heard on the streets. Restaurants like Praha and Vasata, heavy on the goose, duck, pork, and dumplings, are long defunct.

The Little Slovakia bar has vanished, and markets, bakeries, relief organizations, and travel agencies catering to Czech and Slovak immigrants closed their doors long ago.

Yet traces do exist of the former Czech neighborhood centered on East 72nd Street between First and Second Avenues. Created after waves of immigration in the late 19th century and then again in the 1940s, Little Czechoslovak once had a population of 40,000—with many finding work in local breweries (alongside their German neighbors in Yorkville) and cigar factories in the east 70s.

One of the oldest remnants stands on East 71st Street near First Avenue. This beige brick Renaissance-style structure opened in 1896, and its name is still carved into the facade: Cech Gymnastic Association. (Interesting side note: The architect is the same man who designed the building that housed the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory on Washington Place.)

The Gymnastic Association, or Sokol Hall, was an elegant community center. “Old photographs show a space full of gymnastic equipment, ringed by a great oak gallery and painted like a European concert hall—marbleized columns and elaborate stencil and decorative work on the walls,” wrote Christopher Gray in the New York Times in 1989.

“The hall was a centerpiece for the Czech community in New York, offering dinners, theatrical events, concerts, bazaars and a comfortable social club.” Sokol Hall still operates as a gym, though the restaurant (see the sign above in a photo from 1940) seem to have vanished.

All of New York’s former ethnic neighborhoods had their own funeral parlors, and Little Czech is no exception. John Krtil got its start in 1885, and it’s the only one that remains, on First Avenue at East 70th Street.

Immigrant enclaves always built churches. St. John Nepomucene Church is one that survives; it’s a stunningly beautiful Catholic church at First Avenue and East 66th Street. The parish was founded by Slovak immigrants in the East Village before relocating here in 1925, according to Slavs of New York.

Inside St. John’s recently, I met a parishioner who’d been going to this church since he was a child and recalled the huge congregation and holiday parties in the basement.

I’d passed the Jan Hus Presbyterian Church many times over the years and was eager to include it here. Completed in 1888, this Gothic Revival church on East 74th Street off First Avenue was one of the earliest houses of worship to serve the Bohemian community.

What a surprise to find it impossible to view behind heavy scaffolding! The church building was sold to the Church of the Epiphany, which is doing a heavy renovation. Jan Hus Church will be moving to 90th Street and First Avenue. (The photo above was shot before the building went into hiding; it’s from the Historic Districts Council.)

“The [Jan Hus] Church design evokes the streetscape of Prague with its distinctive Romanesque and Gothic Revival details, including a tower said to recall the entrance to Charles Bridge, which was added in 1915 as part of the expansion,” wrote Majda Kallab Whitaker, in a thoughtful farewell on the website for the Bohemian Benevolent and Literary Association.

Luckily Bohemia National Hall is still with us. Completed in 1896, this stunning five-story building on East 73rd Street could be described as the heart of the neighborhood. “Since its beginning it has served as a focal point for its community, offering ethnic food, Czech language and history classes as well as space for its large community to meet and hold various events,” the Hall’s website states.

With its lion heads on the facade and beautiful arched upper windows, the Hall serves a new purpose these days. Owned by the Czech Republic since 2001, it’s the headquarters of the Czech consulate, according to the New York Times. It’s also the site of a restaurant, Bohemian Spirit, that serves the kind of Czech and Slovak food once dished out in the small cafes and eateries in the neighborhood,

[Third photo: NYC Department of Records and Information Services; seventh photo: Six to Celebrate/Historic Districts Council]