Esther Crain's Blog, page 68

March 22, 2021

When everyone in New York ate at the Automat

The tables were clean, the machines that dispensed coffee, sandwiches, pie, and other items always in order, and the food actually tasty—at least, that’s what New Yorkers who had the opportunity to eat at a Horn & Hardart Automat always say.

The Automat was a welcoming place for newcomers to New York City as well as those who didn’t have much more than loose change to buy their meals. At their peak the city had at least 50 Automats. The spirit of the Automat was a democratic one, according to this rhyme from a 1933 Sun article:

‘Said the technocrat

To the Plutocrat

To the autocrat

And the Democrat—

Let’s all go eat at the Automat!’”

If only we all could still…the last one closed up shop in Manhattan in 1991.

The short life of a 1960s East Village rock venue

The unassuming building a 105 Second Avenue has a long history catering to popular entertainment.

In the 1920s, the venue served as a Yiddish Theater at a time when Second Avenue had so many similar theaters, the street was nicknamed the Jewish Rialto. By the 1940s, the space was turned into a movie palace known as the Leow’s Commodore (below in 1940).

And in the 1960s it was transformed once again for an entirely different audience: young rock fans flocking to the recently christened East Village eager to see bands like the Doors, the Allman Brothers, and other stars of the late 1960s music scene.

Named the Fillmore East by concert promoter Bill Graham and opened on March 8, 1968, it was the New York version of his San Francisco concert hall the Fillmore. With Graham at the helm, the place became legendary.

“Graham operated a tight ship, demanding nothing less than excellence from his staff and the artists who inhabited his stage,” wrote Corbin Reiff in a 2016 Rolling Stone article.

“To him, everything was about the fan experience, and he went out of his way to provide the best kind of atmosphere to take in a live performance, from the ornate, hand-rendered posters he printed up to announce the gigs…and even the barrel of free apples he left out for people departing at the end of the night.”

“As a result, the bands and artists who played the Fillmore East, as well as its San Francisco counterpart, typically went the extra mile,” continued Reiff. “For just $3, $4 or $5, you, as a ticketholder, were granted a pass to be taken to someplace truly magical.”

Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix, Neil Young, Led Zeppelin, and Pink Floyd all hit the stage. But it might have been the Doors who gave the most hypnotic performance.

In the audience for one of their shows was future star Patti Smith; Robert Mapplethorpe had worked there and gave her a free pass. She recounted the experience in her powerful memoir about their relationship amid the late 1960s and early 1970s city in Just Kids. While the audience was transfixed by Jim Morrison, she “observed his every move in a state of cold hyperawareness.”

“He exuded a mixture of beauty and self-loathing, and mystic pain, like a West Coast Saint Sebastian,” wrote Smith, who right then realized she could do what Morrison was doing. “When anyone asked how the Doors were, I just said they were great. I was somewhat ashamed of how I had responded to their concert.”

For a rock venue with such a hallowed reputation, it lasted a very short time—just three years. “At the time, Mr. Graham blamed the greediness of some top rock musicians who he, said would rather play a 20,000‐seat ball like Madison Square Garden (one hour’s work, $50,000) than the 2,600‐seat Fillmore East (about four hours’ work, roughly $20, 000),” stated the New York Times on the club’s closing night, June 29, 1971.

That wasn’t the end of 105 Second Avenue’s life as a music venue. In the 1980s it was resurrected as the dance club The Saint. Today, the ground floor is—what else?—a bank branch.

[Top photo: NYC Department of Records and Information Services; second image: ultimateclassicrock.com; third image: Yale Joel/LIFE Magazine]

March 21, 2021

Why “Houston Street” is pronounced that way

You can always spot a New York newbie by their pronunciation of wide, bustling Houston Street—as if they were in Texas rather than Manhattan.

But the way New Yorkers pronounce the name of this highway-like crosstown road that serves as a dividing line for many downtown neighborhoods begs the question: Why do we say “house-ton,” and what’s the backstory of this unusual street name, anyway?

It all started in 1788 with Nicholas Bayard III, owner of a 100-acre farm located roughly in today’s SoHo (one boundary of which is today’s Bayard Street).

Bayard was having financial difficulties, so he sold off parcels of his farm and turned them into real estate in the growing young metropolis, according to a 2017 New York Times piece. “The property was converted into 35 whole or partial blocks within seven east-west and eight north-south streets, on a grid pattern,” explained the Times.

Bayard decided to name one of those east-west streets after the new husband of his daughter Mary, William Houstoun (above)—a three-time delegate to the Continental Congress from Georgia. Houstoun’s unusual last name comes from his ancient Scottish lineage, states Encyclopedia of Street Names and Their Origins by Henry Moscow.

The street name, Houstoun, is spelled correctly in the city’s Common Council minutes from 1808, wrote Moscow, as well as on an official map from 1811, the year the grid system was invented. (It’s also spelled right on the 1822 map above).

In the 19th century, the city developed past this former northern boundary street. East Houston Street subsumed now-defunct North Street on the East Side and extended through the West Side (above photo at Varick Street in 1890). At some point, the spelling was corrupted into “Houston.”

The Times proposes a possible reason why the “u” was cut: Gerard Koeppel, author of City on a Grid: How New York Became New York, thought it could have to do with Sam Houston emerging in the public consciousness in the 1840s and 1850s as senator and governor of Texas.

Whatever the reason, the new spelling stuck—with the original late 18th century pronunciation.

[Top Image: Danny Lyon/US National Archives and Records Administration via Wikipedia; Second image: Wikipedia; third image: Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc.; fifth image: New-York Historical Society; sixth image: MCNY 1971 by George Roos x2010.11.763]

March 15, 2021

The 1911 New York fire that changed history

On the eighth floor of a women’s garment factory steps from Washington Square Park, a fire broke out in a wood bin filled with fabric scraps. It was about 4 pm on a Saturday, and the workday should have been ending.

Instead, the blaze grew, reaching the ninth and tenth floors of the factory. When workers tried to escape, they encountered locked doors. One fire escape collapsed to the ground under the weight of desperate employees.

Many of those trapped in the upper floors jumped to the sidewalk in front of horrified onlookers, others burned in the flames because firefighters’ ladders were too short to reach the windows. A total of 146 workers were killed in the fire of March 25, 1911—mostly young female immigrants.

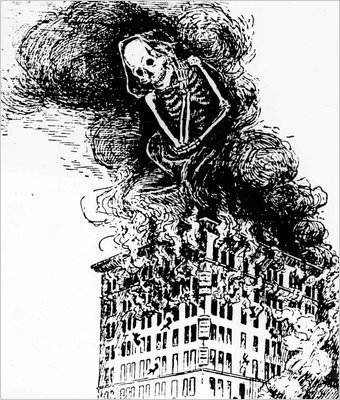

As tragic as the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire was, the terrible toll had a profound effect in New York City—leading to stricter workplace safety laws and harsher legislation protecting workers. These new mandates had strong support from an outraged public, whose horror was reflected in piercing illustrations that appeared in newspapers for weeks.

This one above is by John Sloan, published in The Call. The illustrator of the second image is unknown, but that sure looks like the Asch Building, where the Triangle fire occurred.

A ghost sign for a family business on Essex Street

Back in 2010, a lounge and restaurant called Beauty & Essex opened in a cavernous space at 146 Essex Street—a glittery addition to Lower East Side nightlife back when the neighborhood still had a grittier edge.

Beauty & Essex is temporarily closed, according to Yelp. But there’s another reason to do a walk-by at this address: to see the faded ghost sign that still remains on the facade decades after it went up in the 1960s.

This spot used to be the home base of M. Katz & Sons Fine Furniture—a business founded in 1906 out of a Lower East Side tenement by Meilich Katz, according to the store website. In the 1930s, M. Katz’s sons opened a shop on Stanton Street, and by the late 1960s, a third generation relocated to 146 Essex Street (below, an undated photo of the Essex Street sign).

M. Katz’s still sells furniture; a fifth generation of the Katz family occupies a smaller space on Orchard Street these days. The facade on Essex Street is a palimpsest of a century-old family business still bearing the founder’s name.

[Second photo: Yellowbot]

Tracing Berenice Abbott’s steps in today’s Bowery

After spending the 1920s as a cutting edge portrait photographer in Paris, Berenice Abbott returned to the United States to find that her documentary-like style of photography was out of fashion.

In New York, Abbott “was unable to secure space at galleries, have her work shown at museums, or continue the working relationships she had forged with a number of magazine publications,” states the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

Lucky for Abbott—and for fans of her unromanticized images that speak for themselves—the Federal Art Project came calling. In 1935, it gave her the means to photograph the streets, buildings, and people of New York City. More than 300 resulting images were collected in Changing New York, published in 1939.

Though Abbott aimed her camera all over Manhattan and parts of Brooklyn, she was especially drawn to the Lower East Side, specifically the Bowery. At the time, the Bowery was a “Victorian entertainment district turned skid row, which she likened to ‘wandering through hell,'” according to the text of a 1997 edition of the book by the Museum of the City of New York.

Retracing Abbott’s steps through the Bowery, as documented in Changing New York, is possible today because she kept track of the addresses of the three storefronts she captured.

The top photo, at 103 Broadway, might be one of Abbott’s most famous New York images. This “hash house,” as the Blossom Restaurant was known per the MCNY’s Changing New York, occupied the ground floor while Jimmy the Barber worked out of the basement. The two men in the shot have the harsh expressions expected of men who catered to Bowery bums.

Below it is the storefront today. It’s still a food establishment, but the space has been remodeled. The aura of danger and depression are gone.

The striking storefront—and colorful claims designed to lure men of few means—of the Tri-Boro Barber School (“world’s most up-to-date system”) probably appealed to Abbott. The school was at 264 Bowery, which was lined with barber shops at the time, states the MCNY’s updated Changing New York: “Upon completion of a 10-week course, a student was a ‘full-fledged professional barber’ and could find a job at a starting union wage of $22.50 per week.” Below it is 264 Bowery now, with its similar doorway but ghostly, empty space.

This hardware store at 316-318 Bowery has the crammed feel of a dollar store, proving that the tradition of an overload of seasonal merchandise and lots of sale signs lives on in 21st century New York. “Hardware emporiums, catering to tradesmen from all over the city and day laborers who lived nearby, flourished on the Bowery,” states the MCNY’s Changing New York. The storefront today appears to be another COVID casualty.

Would Abbott be as drawn to the Bowery of 2021 as she was to the Bowery of the 1930s (above, under the elevated at Division Street and Bowery)?

Probably not. This storied main drag that had a brief fling as an elite address in the early 19th century before becoming synonymous with tawdry entertainment, flophouses, and cheap bars now resembles many other Manhattan streets of the 21st century—lacking the signs of desperate humanity Abbott was attracted to.

[Top photo: Smithsonian National Museum of American History; third photo: Artnet; fifth photo: Wikipedia; sixth photo: MutualArt]

March 8, 2021

An old New York phone exchange on 47th Street

Spotted on an unremarkable building on West 47th Street in the Diamond District: an old-school New York City phone exchange, in this case “MU.”

What does it stand for? Murray Hill, of course, the neighborhood where the real estate company that put up this plaque is based.

It’s getting harder to find these two-letter exchanges, which were replaced by numerals in the early 1960s. But they’re out there—especially in the boroughs outside Manhattan.

A short-lived road named for a female scientist

Since its creation in the 1880s, it was unceremoniously called Exterior Street—a slender road east of York Avenue between 53rd and 80th Street that ran closest to the East River. It existed primarily to provide access to the river for industry.

But in 1935, a prominent New Yorker came up with an idea. She wanted to rename a stretch of Exterior Street in honor of Marie Curie, the Polish-born, Nobel Prize–winning scientist who discovered the elements polonium and radium and died a year earlier from the effects of radiation from her own research.

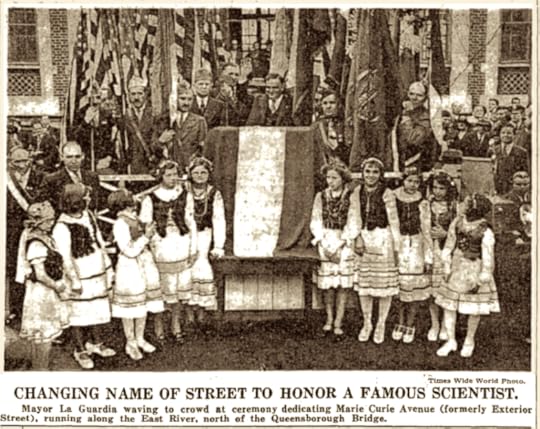

Mayor LaGuardia had already held a ceremony honoring Curie in City Hall Park in November 1934. There, he and his Parks Commissioner, Robert Moses, unveiled a plaque dedicated to Curie (fourth photo below) as well as a tree planted in her memory, according to a 1999 article in The Polish Review by Joseph W. Wieczerzak.

A rare female scientist at the time, Curie was a heroic figure worldwide but especially in America, thanks in part to her development of mobile X-rays brought to the front line in France during World War I that “did much to lessen the suffering of wounded soldiers,” wrote Wieczerzak.

Mary Mattingly Meloney, the influential editor of the New York Herald-Tribune’s Sunday magazine and a personal friend of Curie’s, appealed to Mayor LaGuardia to create a Marie Curie Avenue in Manhattan. The idea was quickly brought to a vote before the Board of Alderman, and it passed unanimously.

Why was Exterior Street chosen for the honor? First, “Exterior” was really just a generic name for an industrial, riverfront road. But also, several medical facilities—like Rockefeller Institute, later University—built their headquarters nearby on York Avenue, states Wieczerzak. It seemed fitting to have an avenue to the east named for a scientist, even though that street wasn’t always so attractive, as the photos suggest.

The official renaming took place on June 8, 1935, in a ceremony attended by 5,000 people, according to the New York Times. Despite the fanfare, Marie Curie Avenue would only officially last for five years.

The street was doomed in 1935, when plans were unveiled for the East River Drive. “Construction of the drive began in 1937,” wrote Wieczerzak, adding that parts of Marie Curie Avenue were widened, leveled, and elevated before being covered in 1939 or 1940 by the “rubble from bomb-destroyed buildings of British cities carried as ballast in ships docking in New York Harbor to load wartime cargo.”

The East River Drive opened in 1940…and it was eventually renamed for Franklin Delano Roosevelt. I don’t think a trace of Marie Curie Avenue—the first major street named after a woman in New York City—remains.

[Top photo: NYPL; second photo: Nobelprize.org; third photo: MCNY X2010.11.2542; fifth photo: NYT July 10, 1935; sixth photo: NYPL]

March 7, 2021

A lethal hotel fire at the St. Patrick’s Day parade

When the Windsor Hotel was going up in the early 1870s, it was one of the modern new buildings transforming sleepy Fifth Avenue above 42nd Street into the “storied splendor of the future of New York City,” as the New York Times excitedly wrote at the time.

“The Windsor is to be a first class hotel in every respect, and not to be excelled in general arrangements, size of rooms, attendance and completeness by any establishment of the kind,” stated the Times in May 1872, in a glowing review of the plans for the 500-room, seven-story hotel, which was set to open a year later at Fifth and 47th Street.

The timing couldn’t have been better for the Windsor. Not only was Fifth Avenue all the way up to 59th Street at Central Park booming during the Gilded Age, but hotel living was becoming a popular alternative to owning a single-family mansion for many wealthy New Yorkers.

Yet 26 years later, a carelessly tossed cigarette would reduce to hotel to smoldering rubble—and crowds lining Fifth Avenue to watch the annual St. Patrick’s Day parade (below, in 1904) found themselves witnesses to desperate hotel guests jumping to their deaths to escape the flames.

The fire started around 3 in the afternoon on March 17, 1899. A hotel guest reportedly lit his cigarette or cigar with a match in the second-floor parlor, then tossed the match out the window. But instead of falling to the street, the lit match was blown into a curtain. Almost instantly, the fire spread across the drapes and to the wall, according to the Times the day after the blaze.

The fire moved fast inside the hotel. But outside was a festive scene, with paraders “marching gayly up Fifth Avenue in front of the hotel, and thousands of people keeping time to the lilt of Irish tunes, while hundreds watched from the windows of the hotel the passing troops and waving flags,” the Times reported.

The head waiter at the Windsor, John Foy—who tried to stamp out the flames when they were still confined to the drapes—raced outside to the street yelling fire, but his cries were “drowned out by the music.” He tried to alert a policeman but was told to get back.

Finally the flames engulfed the second-floor parlor, and the smoke began to attract the attention of parade watchers before the fire exploded upward.

“Women turned pale and screamed, little ones shrank back sobbing, and men felt the sweat break upon their brows, as the heads of panic-stricken people protruded from the hotel windows…calling for help in tones that made the hearers sick,” the Times reported.

Guests trapped in their rooms had one escape route: they could climb out the window via the safety rope installed in every room—this is what passed for a fire safety exit at the time. But many people who started down the ropes ended up letting go because of the friction of the rough rope against their hands—and they subsequently plunged to the sidewalk, the Times wrote.

Firemen came to the scene quickly, but “milling thousands” of parade watchers prevented the firemen from getting inside the building easily. By the time they did, the Windsor ‘was blazing like an oil-soaked rag in a pitch barrel,” according to a Popular Science article that reexamined the fire in 1928.

The final death toll was estimated to be 86. Many of the bodies suffered so much trauma, they went unidentified and buried in an unmarked mass grave in Kensico cemetery in Westchester.

[image error]“The Windsor, although it was the most fashionable residence hotel in the city, was a veritable tinder box, ‘built to be burned,’ fire chief John Kenyon said, per Popular Science. “It has no fire escapes, no standpipes, no fire buckets. In short, it represented the worst type of the old-style ‘quick burner.'” Kenyon was a lieutenant at the time of the fire, but as FDNY chief in 1907 he was responsible for the first high-pressure hydrant system in the city.

This terrible tragedy loomed large for decades. It was even turned into a song—dedicated to Helen Gould, widow of financier/robber baron Jay Gould, who lived near the hotel and turned her “double house” mansion into a makeshift hospital to treat the injured. But over time, the Windsor receded in the city’s collective memory.

Yet there is a recent poignant twist to the story: In 2014, the unidentified victims who perished in the fire and were interred in Valhalla finally got a black granite monument to mark the mass grave. “They’re all unidentified and cemeteries are about memorialization,” Chet Day, Kensico’s president, told local paper lohud in 2014. “I felt something had to be done.”

[Top image: MCNY 91.69.15; second image: New-York Historical Society; third image: NYPL; fourth image: MCNY X2010.11.9345; fifth image: MCNY X2010.11.9340; sixth image: MCNYX2010.11.9354; seventh image: MCNY X2010.11.9350; eighth image: Lester S. Levy Sheet Music Collection, Johns Hopkins University]

March 1, 2021

A postcard shows off the pretty girls of New York

Most of New York City’s vintage postcards feature beautiful sites of the city itself—not Gotham’s beautiful women. But this turn-of-the-century postcard is a strange exception to the rule.

“Pretty girls, pretty girls everywhere, but the New York belles are claimed most fair” reads the caption, with the images of six women, none of whom I recognize but could be actresses of the era.

The inset image of Herald Square is interesting—perhaps it’s pictured because West 34th Street was part of the Theater District at the time, and it was the place to see these and other “New York belles.”