Esther Crain's Blog, page 64

July 4, 2021

The story of the twin former horse stables of Great Jones Street

If you walk down Great Jones Street between Lafayette and the Bowery, you’ll come across these handsome Italianate-style red buildings with almost identical black cornices.

Built by separate developers in 1871, the sign in the center of each cornice indicates that both buildings were used as stables. Like so many other former stables throughout New York, they were converted to residences with ground floor commercial space once automobiles replaced equines in the early 1900s.

True, both of these buildings originally did house horses. But while the sign on the cornice of one is authentic, the signage on the other was only put up in the 1970s.

The Great Jones Street stables in 2011, without scaffolding

The Great Jones Street stables in 2011, without scaffoldingLet’s start with Number 33, on the left. The slightly damaged letters on the cornice read “Beinecke & Co’s Stables.”

Who was Beinecke? Johann Bernhard Georg Beinecke immigrated from Germany via Castle Garden in 1865, according to the website Immigrant Entrepreneurship.

His is a rags to riches story. “Bernhard signed on as a wagon driver for a meat concern; within a few short years he bought the company and appropriately renamed it Beinecke & Company,” the website continues. Later, he branched out into banking and the hotel business, buying the original Plaza Hotel and other luxury hotels.

From 1890 into the 20th century, the horses that pulled the delivery wagons for the Beinecke meat company were stabled here, states the Landmark Preservation Commission’s NoHo Historic District Extension Report.

And what about Number 31 on the right? This building was originally the home of the New York Board of Fire Underwriters, and the LPC Report says the Underwriters board moved its Fire Patrol No. 2 here from 1873 to 1907. (At the time, of course, a fire patrol needed fire horses.)

“Following the departure of the Fire Patrol, the building was converted to other uses,” states the LPC report. One of those was home base for the Joseph Scott Trucking Company. This business established itself at 59 Great Jones Street in 1966 before relocating to Number 31 in the 1970, and then moved a third time to Number 33 until 1997, according to Walter Grutchfield.

Numbers 33 and 31 in 1980, by Edmund Vincent Gillon/MCNY

Numbers 33 and 31 in 1980, by Edmund Vincent Gillon/MCNYAt some point, the trucking company added their own signage—copying the late 19th century look of Beinecke & Sons. “This is a modern cornice/pediment inscription meant to immulate its neighbor at 33 Great Jones Street,” Grutchfield writes.

Two 19th century former stables, but only one authentic stable sign.

[Second photo: Wikipedia; fifth photo: Edmund Vincent Gillon/MCNY 2013.3.2.1790]

June 28, 2021

A West Side historic district packed with Queen Anne beauty

Walking along Manhattan Avenue feels like being in on a secret. Part of it has to do with the street itself, which is quiet and slender, tucked between Columbus Avenue and Central Park West and only running from 100th to 125th Streets.

Then there’s the architectural eye candy on both sides of Manhattan Avenue: three blocks of confection-like Queen Anne and Romanesque Revival row houses with all the terra cotta detailing and ornamental bells and whistles you could ask for from these two eclectic styles popular in the late 19th century.

These three blocks at the lower end of the avenue make up the Manhattan Avenue Historic District, which fronts 104th to 106th Streets and includes a few buildings on side streets. (There’s a second Manhattan Avenue Historic District from 120th to 123rd Street as well.)

Manhattan Avenue’s secretive vibe also might have to do with the fact that it wasn’t part of the 1811 official city street grid that mapped out Manhattan.

“Laid out as ‘New Avenue’ in 1872-73, this late addition to the Manhattan gridiron received its current name in 1884,” wrote Andrew Dolkart in Guide to New York City Landmarks. “The district contains 37 row houses, a six-story apartment building, and two structures built as part of General Memorial Hospital, originally known as the New York Cancer Hospital.”

When the Upper West Side—then known as the West End—transitioned from a collection of farm villages to an urban residential area in the late 19th century, the lovely row houses in this historic district went up as well. The busiest years spanned 1886 to 1889, the same time period when the Manhattan Avenue Historic District houses were built, according to the Landmark Preservation Committee (LPC) Report from 2007.

“The earliest group, located on the west side of the Avenue between 105th and 106th Streets, was designed by Joseph M. Dunn,” states Dolkert. “Opposite these buildings is an early row by C.P.H. Gilbert, who later became one of the city’s best-known residential architects.” A third group of rowhouses were then built on the west side between 104th and 105th Streets.

The first residents of these homes were upper middle class folks, states LPC report. “The United States Census of 1900 indicates a wide variety of occupations, including salesmen, real estate brokers, a janitor, engineer, pressman, teacher, bookkeeper, dentist, and physicians,” the report details. In subsequent years, lodgers and boarders were also recorded.

As New York City’s fortunes rose and fell in the 20th century, so did the cache and character of Manhattan Avenue. Today these flamboyant houses are restored and well cared for, part of the quiet enclave of Manhattan Valley.

Number 127 went on the market last year for $2.5 million—many times more than the cost of the houses estimated by the original builders, which was in the neighborhood of $10,000 each, per the LPC report.

June 27, 2021

One summer night on a New York tenement roof

Saul Kovner was a Russia-born artist who came to New York City in the 1920s. After attending the National Academy of Design and setting up a studio on Central Park West, he worked for the WPA in the 1930s and 1940s.

Kovner captured gentle yet honest scenes in all seasons of urban life, particularly of working class and poor New Yorkers. In 1946, he completed “One Summer Night,” a richly detailed depiction of tenement dwellers seeking refuge from the heat in a pre- air conditioned city.

I’m not sure what part of the city we’re in, but you can just feel the sweat, discomfort, and frustration—that sense of being trapped, as these people are, on a tarry island that offers little relief.

“One Summer Night” gives us a situation any New Yorker living in the city in a tenement can relate to. No wonder so many social realist artists have painted or illustrated similar scenes in the late 19th and 20th centuries. Here’s how John Sloan, Everett Shinn, and some wonderful unidentified illustrators captured the “fiery furnace” of a New York heat wave.

Two mystery gargoyles on a 57th Street building

When you walk along New York City streets, you never know who is looking down at you. And on a busy corner at West 57th Street and Broadway, you’re getting the evil eye from two mysterious grotesques.

These stone figures are affixed to what was once the main entrance for the Argonaut Building—a terra cotta beauty with Gothic touches that opened in 1909.

Back then, the building was the showroom for the Peerless Motor Car Company, a long-defunct carriage and car manufacturer that vacated the premises in the 1910s.

This stretch of Broadway near Columbus Circle was known as Automobile Row, thanks to all the car showrooms that popped up there in the early 20th century.

After Peerless (above, in a 1909 ad) left, General Motors took it over. Eventually the building was renovated and converted to office use. The Hearst company bought it and based many of their consumer magazines here through the 2000s.

When it was important to have a presence in this car-showroom neighborhood, Peerless made sure they occupied prime real estate.

But they also designed the building to fit into the corner, which explains why it has the Gothic look of the Broadway Tabernacle Church, which held court on Broadway and 56th Street (above photo, likely from the 1940s).

But back to the grotesques. Spooky and sly, laughing or crying out, they’re either holding up the building or hiding under it with sinister intentions. Shrouded in what looks like robes and slip-on shoes, they’ve been with the building since the beginning…and are apparently here to stay.

[Third image: New-York Tribune, December 12, 1909; fourth image: NYPL Digital Collection]

June 20, 2021

This massive stone mansion stood for just 26 years on Fifth Avenue

When railroad baron H.H. Cook decided to build himself a New York City mansion, he didn’t try to squeeze into a plot of land on Fifth Avenue in the 50s—an area that had been colonized by several Vanderbilt heirs and other Gilded Age moneymakers.

The H.H. Cook mansion in 1891, with few neighbors

The H.H. Cook mansion in 1891, with few neighborsInstead, he went to the then-hinterlands of Manhattan, purchasing the entire block from Fifth to Madison between 78th and 79th Streets. There he oversaw construction of his monumental stone house, which was completed on the corner of Fifth and 78th Street in 1883.

The cost of this exuberant, somewhat incongruous (are chimneys coming out of the dormer windows?) marble and sandstone home: $500,000, a hefty sum at the time, even for a millionaire.

The mansion circa 1900

The mansion circa 1900He seemed determined to make the most of his investment. “Mr. Cook was very much interested in the building of the mansion, and it was his wish to make it one of the finest in the city,” stated the New York Times in 1909.

“Every detail of its construction was carefully looked after, and the building was done by ‘day’s work’—that is, there was no general contract to have it done at a certain time or at a certain cost, but the progress of the work was watched and if any particular feature did not please the owner it was taken out or altered.”

The Cook mansion became something of a monument at the time, and it likely lured other rich New Yorkers out of Murray Hill and other posh enclaves to this upper stretch of Fifth Avenue. By the 20th century, even Mrs. Astor relocated there, along with Andrew Carnegie.

Wurts Bros. photo showing many neighbors now

Wurts Bros. photo showing many neighbors nowCook wouldn’t live in his mansion very long, though. “After occupying it for 20 years, Cook became tired of the large place,” according to a 1930 New York Times article. He began construction on a smaller, more up-to-date one next door but never moved in; he was spending much of his time at his Berkshires estate in Massachusetts.

He died in 1905. Four years later, tobacco scion James B. Duke purchased the mansion, intending to renovate it. Duke changed his mind and had it bulldozed that year, constructing a more elegant mansion that still anchors the corner today, below. (It’s now owned by NYU.)

The James B. Duke mansion replaced Cook’s house, seen in 1938

The James B. Duke mansion replaced Cook’s house, seen in 1938“‘They don’t put buildings up that way now,” a watchman at the house said to a New York Times reporter, who wrote an elegy to the mansion in 1909 as it was “being taken to pieces and the material turned over to the second-hand men.”

Though Cook’s mansion only stood for a mere 26 years, his influence on the block lasts to this day. When he bought all the lots back in the early 1880s, he decided to sell them off only to developers intending to build single-family homes. “Cook’s Block” became known as one of the most restricted in Manhattan. Thanks to his foresight, the newest building fronting Fifth Avenue between 78th and 79th Streets is the Duke place, completed in 1912.

[First image: Digital Culture; second image: MCNY 93.1.1.16686; third image: MCNY X2010.7.2.25117; fourth image: NYPL]

An eccentric loner paints New York at dusk and in moonlight

Louis Michel Eilshemius had the right background to become an establishment painter.

“New York at Night,” 1910

“New York at Night,” 1910Born to a wealthy family in New Jersey in 1864, he was educated in Europe and then Cornell University. After persuading his father to let him enroll in the Art Students League and pursue painting, he returned to live at his family’s Manhattan brownstone at 118 East 57th Street.

His early work earned notoriety and was selected for exhibition at the National Academy of Design in the 1880s.

“Eilshemius’s early artistic style was rooted in lessons he gleaned from his studies abroad, specifically the landscape aesthetics of the Barbizon School and French impressionism,” states the National Gallery of Art.

“New York Rooftops,” undated

“New York Rooftops,” undatedIn the 1890s and 1900s he traveled the world, published books of poetry and a novel, and continued to paint. But what one critic called his “outsized” ego led Eilshemius, by all accounts a loner and eccentric, to reject the contemporary art scene.

“By 1911, disconcerted by the lack of attention his paintings attracted, he had renounced his formal training and transitioned to an entirely self-conscious and seemingly self-taught style.”

That self-taught style was dreamy, romantic, and visionary. Influenced by reclusive 19th century painter Albert Pinkham Ryder, it was described as having a “sinister magic.”

“Autumn Evening, Park Avenue,” 1915

“Autumn Evening, Park Avenue,” 1915“The paintings of this time became increasingly less conventional and punctuated by an element of fantasy, depicting voluptuous nudes and moonlit landscapes,” states the Michael Rosenfeld Gallery. “With whimsical flourish, Eilshemius also painted sinuous frames onto these pictures, thereby adding both dimensionality and flatness to his lyrical and romantic scenes.”

Though he isn’t known as a New York City streetscapes painter, Eilshemius seems to have occasionally painted the city around him—creating muted, mystical scenes of Gotham’s shabbier neighborhoods in twilight and moonlight.

As Eilshamius turned away from the art world, he became more of an oddball, a “bearded, querulous, erratic man whose gaunt figure was a stock one in the galleries that never hung his work,” according to his obituary in the New York Times.

“East Side New York,” undated

“East Side New York,” undatedNow he was living in the dusty family brownstone with just his brother, Henry. When he wasn’t haranguing gallery owners to buy his work, he was handing out pamphlets touting himself as an artistic genius, or writing thousands of letters to city newspapers. (The Sun printed some of them under amusing headlines, states his obituary.)

As the 20th century went on, however, Eilshemius was rediscovered by the art world. In the 1920s and 1930s he had numerous exhibits, and his talent was recognized by the critics of the era.

“At this time, his success both confounded and fueled his perceived peculiarities and erratic behavior and, injured in an automobile accident in 1932, Eilshemius became increasingly reclusive,” according to the Michael Rosenfeld Gallery.

“New York Street at Dusk,” undated

“New York Street at Dusk,” undatedWhen Henry died in 1940, Eilshemius was left ailing and impoverished in the family’s “gloomy, gaslit” brownstone. In 1941 he came down with pneumonia, but he protested going to the hospital. so doctors put him in Bellevue’s psych ward.

He died in December of that year, in debt but with the recognition he always wanted.

“A feisty rebel and a tireless iconoclast, he never painted to satisfy the fashions of his day, but only to please his own strange and sometimes nightmarish vision,” wrote David L. Shirey in the New York Times in 1978, in a piece on an exhibit of Eilshemius’ work. “It was a vision characterized by extraordinary personal insight and imagination.”

June 14, 2021

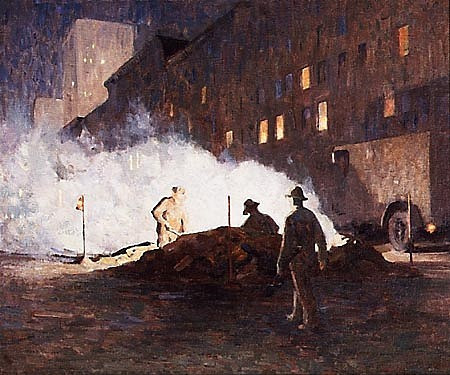

The steam pipe repair crew fixing New York at night

Born in New York City in 1901, painter Dines Carlsen made a name for himself as a still life and landscape painter. Here he made nighttime New York City his landscape, focusing on the men called out to do the rough work of fixing steam pipes while most of the city sleeps.

“Steam Pipe Repair Crew” is undated, and I’m not sure where it’s set. Though the scene takes place likely in the first half of the 20th century (based on the clothes and truck), it depicts a situation that occurs multiple times every night, night after night, somewhere in New York—people doing their jobs out of sight under darkness, when most of us are unaware.

[Cavalier Galleries]

The anti-slavery past of a Bowery house built in the 1790s

Numbers 134 and 136 Bowery, between Broome and Grand Streets, look like they were designed to be twins.

Both houses were constructed when the Bowery was a fashionable address north of the city center. Each reflects the Federal style that was in vogue at the turn of the 19th century—with dormer windows, steep roofs, and Flemish-bond brickwork.

But 134 Bowery (on the left) has the edge when it comes to New York history. This 3-story house dates back to the 1790s, still extant in Manhattan. Number 136 is old by Gotham standards, but it didn’t go up until 1828, according to the Bowery Alliance.

Sources vary on who built the houses, but one or both were constructed and occupied by Samuel Delaplaine and his family. Delaplaine, a Quaker, was an outspoken member of the city’s nascent abolitionist movement.

“…may servitude abolish’d be, As well as Negro-Slavery, To make one LAND of LIBERTY!” read a manifesto Delaplaine reportedly wrote in 1793, according to The Historical Markers Database. (Below, 134-136 Bowery two doors down from the bank building on the left in 1910.)

Delaplaine’s ancestors made their wealth as merchants. “The Delaplaines were descendants of a Huguenot refugee who landed in New Amsterdam after fleeing France,” states Alice Sparberg Alexiou in her book, Devil’s Mile: the Rich, Gritty History of the Bowery.

His Quaker faith may have spurred on his opposition to slavery, which was legal in New York City until 1799, when the first of a series of gradual emancipation laws were enacted. (New York state fully abolished slavery in 1827.)

In 1795, he donated the land for St. Philips Church, New York’s first black Episcopal church, notes Alexiou, which originally stood on Centre Street. He also donated plots he owned on Chrystie and Rivington Streets for a cemetery for black New Yorkers, who made up about 20 percent of the city’s population the time.

“Delaplaine was one of a group of ‘diverse, well-disposed individuals,’ as described by the Common Council, who were well-disposed to the ‘African society’ (‘free people of color’) for a Negroes’ cemetery,” Alexiou wrote.

Delaplaine’s descendants were also active in the abolitionist movement, which became stronger in antebellum New York. “Booksellers and circulating libraries published and distributed anti-slavery literature in these buildings, which also served as boarding houses and possible fugitive-slave safe houses in the 1830s to the 1860s,” states the Bowery Alliance.

After the Civil War, 134 Bowery became one of the first YMCAs located on the Bowery. “Partnering with the New York Mission Society, a reading room and the Carmel Chapel were opened, and food, lodgings, and baths were provided to ‘all persons, without respect to country, creed, color, sex, or age,” per the Alliance.

While both houses have long had commercial tenants on the ground floor, their link to abolition can hopefully save them from the wrecking ball.

“The historic houses at 134-136 Bowery are now documented to be significantly associated with the anti-slavery movement beginning at the end of the 18th century,” wrote Mitchell Grubler at Place Matters. “They meet the established qualifications to be deemed of most important historic value through documented connections.”

[Third image: Library of Congress]

June 13, 2021

A faded Woolworth’s store in East Harlem comes back in view

On a dreary stretch of Third Avenue at 121st Street in East Harlem is a block-long, two-story building emptied of tenants, waiting for the wrecking ball.

But hiding behind a metal frame on the exterior is a throwback to a very different New York: the faded imprint of a Woolworth’s sign against that iconic red backdrop: “F.W. Woolworth Co.”

Before Amazon, before Target, and before Walgreens there was Woolworth’s, the five-and-dime store chain that sold everything from underwear to goldfish to school supplies to sewing patterns throughout the 20th century.

Some had lunch counters, popular places to grab a cheap bite before the era of fast food and Starbucks. (Those lunch counters often attracted the down and out and lonely, as I recall from many, many trips to a Greenwich Village Woolworth’s as a kid.)

Woolworth had a strong presence in New York City. In Manhattan alone Woolworth’s occupied storefronts on Eighth Street, both ends of 14th Street, and all the major cross streets up to 125th Street.

Woolworth’s was once a regular shopping stop for all kinds of necessities; in New York City, they even played a role in the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s. Yet in it’s final decades, the store came off as shabby and doddering.

When the store at 2226 Third Avenue was built and then closed is something of a mystery. The last Woolworth’s in the US shut its doors in 1997.

I have a feeling this Woolworth’s disappeared long before that—though it existed in the 1930s, as the NYPL photo shows above, and it made it into the 1940 NYC tax photo, too.

[Third image: NYPL; fourth image: NYC Department of Records and Information Services]

June 6, 2021

The stars, bars, bubbles, and petals of Manhattan manhole covers

Underfoot all over New York City are late 19th and early 20th century manhole covers embossed with unusual shapes and designs. There’s a practical purpose for this: raised detailing helped prevent people from slipping (and horses from skidding) as they traversed Gotham’s streets in wet weather.

They’re also a form of branding. The city’s many foundries of the era manufactured manhole and coal hole covers. Each foundry company seemed to have chosen a specific design or look to represent them.

And let’s not leave out the artistry that went into these. Manhole covers aren’t typically thought of as works of art, but there’s creativity and imagination in the different designs we walk over and tend not to notice.

J.B. and J.M. Cornell, who operated an ironworks foundry at 26th Street and 11th Avenue, added bubble-like details and smaller dots to their covers, as seen on the example (at top) found in the East 70s near Central Park. They also added swirly motifs on the sides, prettying up these iron lids and making the name and address easier to read.

McDougall and Potter, on the other hand, went for a classic star to decorate this cover on East 80th Street (second photo above). This foundry on West 55th Street also chose bars and dots, within which they included the company name and address.

This cover (above) on 23rd Street near Fifth Avenue, likely by Jacob Mark & Sons on Worth Street, once has colored glass embedded in that hexagram design. A century and then some of foot and vehicle traffic wore them down and pushed some out.

Could those be flower petals decorating the hexagram shape on this cover, also by the Mark foundry? Located near Broadway and Houston Street, it’s unique and charming, especially with the tiny stars dotting the lower end.