Esther Crain's Blog, page 71

January 11, 2021

An early image of ice skaters in Central Park

The building of Central Park began in 1858. Later that year, the first section opened to the public: the “skating pond,” aka the Lake.

You’ve probably seen paintings and illustrations of 19th century New Yorkers ice skating in Central Park and on the ponds of Brooklyn. But this Currier & Ives lithograph (after a painting by Charles Parsons) might be the earliest.

In “Central-Park Winter, the Skating Pond,” it’s 1862, the middle of the Civil War. Yet the frozen pond is a scene of pure joy: couples in fancy skating outfits (yep, they were a thing) glided together, a rare opportunity for socially acceptable coed mingling.

Kids play, adults fall, a dog is getting in on the fun, and everyone is enthralled by the magic of the ice under Bow Bridge.

[Image: Metropolitan Museum of Art]

January 10, 2021

For rent on the Upper West Side in the 1930s

Finding a relatively affordable apartment in a pricey Upper West Side building is no easy feat. But things appeared different in the late 1930s, as a peek at the real estate pages of the New York Times reveals.

The “for rent” section of the paper in August 1938 features dozens of oversize ads dripping with adjectives and images designed to lure tenants—and the vast majority of these ads are for elite Upper West Side addresses.

A combination of factors apparently led to a late 1930s glut of unrented units in the buildings constructed during the Upper West Side boom years of the early 20th century. The Depression must have been a factor, leading to an oversupply of luxury apartments developers were desperate to fill.

Taking a closer look at some of the ads offers an idea of what people were looking for from a New York City apartment in the 1930s—and it also proves that certain amenities never go out of style.

The Master Apartment Hotel ad (top image) is aimed at potential renters who want to “live in a home of art and culture,” with free “lectures and recitals.” One amenity is telling: “silent refrigeration.” Refrigerators became more common in homes in the 1930s, but maybe they sounded like jet engines?

This ad for both 450 West End Avenue and 5 Riverside Drive (second image) is designed for families with kids, and the real estate copy about the great schools is exactly what you’d find in an ad today. But about that second building overlooking the spectacular Schwab Mansion? Well, the mansion was torn down a decade later, so the view would have been of a demolition put and construction site until a replacement went up.

I like the third ad, which covers five of the poshest buildings along the Central Park West of today. “Each building occupies an entire block and enjoys cool breezes and day-long sunshine,” the ad tells us. Clearly this is before air conditioning, and the cool breezes were a real selling point.

370 Riverside Drive was built in 1922, and the list of features—two and three baths, spacious closets, well managed—still have strong appeal. My favorite amenity is the “fine type tenants.” No riffraff here!

Several blocks down Riverside Drive was number 100. Dropped living rooms, Venetian blinds, stall showers, concealed radiators, Kentile kitchen floors…and radio outlets!

Each of these buildings is still standing, and most (if not all) have been converted to co-ops and are part of protected historic districts. About the prices listed: unless otherwise indicated, I believe they cover an entire year.

[All ads are from the August 14, 1938 edition of the New York Times]

January 4, 2021

Old Penn Station’s women-only waiting room

The original Penn Station, opened in November 1910, had many things: a beautiful, spacious building, arcades for high-end stores, 21 tracks for arriving and departing trains…and separate waiting rooms for men and women.

Huh? I’d never come across this until I found this postcard of the women’s waiting room, via the NYPL Digital Collection. It sounds very strange to contemporary sensibilities, but apparently single-sex options for travelers existed.

“In addition to the main waiting room, there were separate waiting rooms for ladies and gentlemen, and a smoking room off the men’s,” stated Jay Maeder in his 1999 book, Big Town, Big Time: A New York Epic 1898-1998.

This diagram of the original station shows the upper part of each single-sex waiting room. No word on when these were phased out, if ever, before the old station was torn down in 1963.

Interestingly, the city considered something similar around the same time as Penn Station opened: single-sex subway cars, so women didn’t have to be subjected to “brutes,” as this 1909 New York Times article about the possibility of female-only subway cars called them. That idea was ultimately abandoned.

[Top image: NYPL; second image: Wikipedia]

Fierce tigers and eagles on a 58th Street co-op

Midtown East is the land of elegant 1920s-era apartment houses: handsome buildings of 10, 11, maybe 12 stories that usually feature understated brick and limestone facades.

But 339 East 58th Street has something else going on: fierce creatures in cast stone above Medieval columns and decorative Romanesque arches.

Adorning this co-op, built in either 1920 or 1929 depending on the source (I’m betting on 1929), are two eagle figures standing ramrod straight like soldiers high above the canopied entrance.

Between these avian sentries are two tiger heads emerging from the brickwork just beneath the second floor windows.

I couldn’t find much information about the building and the backstory of the figures as well as the columns and arches surrounding the entrance.

Perhaps there’s no more significance than an architect tasked with creating yet another standard New York City apartment building while dreaming of Medieval Europe’s soaring cathedrals and castles and taking inspiration from illuminated manuscript pages.

Looking for traces of Sunfish Pond in Kips Bay

Imagine Manhattan Island in the late 1700s. Before it was divided into farms and estates, and before those farms and estates were bricked in and paved over by the end of the 19th century, it was mostly a place of untamed beauty—with woods, swamps, meadows, and streams.

Sunfish Pond illustration, via Patch

Sunfish Pond illustration, via PatchTompkins Square Park was swampland, for example; Collect Pond near City Hall provided drinking water. A trout-filled brook called Minetta flowed through the Village until development diverted it underground. (Evidence of the brook can be seen beneath the lobby of the apartment building at 2 Fifth Avenue.)

And at today’s Park Avenue South and 31st Street was a blob-shaped body of water called Sunfish Pond, which older New Yorkers recalled in turn-of-the-century memoirs.

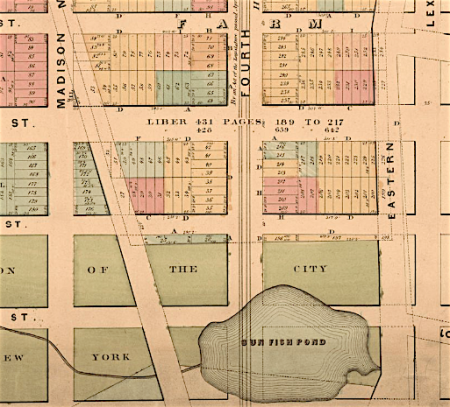

Sunfish Pond, lower right, on an 1867 map of the Ogden Farm

Sunfish Pond, lower right, on an 1867 map of the Ogden FarmSunfish Pond was “bounded by 31st and 33rd Streets and Madison and Lexington Avenues, fed by a stream rising between Sixth and Seventh Avenues at 44th Street, and flowing into the East River between 33rd and 34th Streets,” wrote Charles Haynes Haswell in his 1896 book, Reminiscences of an Octogenarian.

Haswell noted that Sunfish Pond “was a favorite resort for skating,” well beyond the boundaries of the city when he was a boy in the early 19th century.

The stream from Kip’s Bay that fed Sunfish Pond in an 1840 map

The stream from Kip’s Bay that fed Sunfish Pond in an 1840 mapRufus Rockwell, author New York, Old and New, published in 1902, quotes a source who described Sunfish Pond as “famous for its eels, as well as sunfish and flounder.”

The source added that “the brook which fed it was almost dry in summer, but in times of freshet overflowed its banks and spread from the northern line of the present Madison Square to Murray Hill, more than once compelling those who lived along its lower course to resort to boats as the only means of reaching the avenue.”

Inclenberg, aka the Murray Estate

Inclenberg, aka the Murray EstateSunfish Pond would have been located near Inclenberg, the estate owned by Robert Murray and Mary Lindley Murray (whose name now graces the neighborhood of Murray Hill). When the British invaded Manhattan at Kip’s Bay, soldiers may have stopped to drink from this spring-fed pond.

And when the road to the east, Eastern Post Road, became a route for stages running in and out of the city, travelers were known to break here for a rest, wrote Sergey Kadinsky in his 2016 book, Hidden Waters of New York City.

Peter Cooper, namesake of Cooper Union, Peter Cooper Village, and Cooper Square

Peter Cooper, namesake of Cooper Union, Peter Cooper Village, and Cooper Square The beginning of the end of Sunfish Pond was sparked by industry. Peter Cooper, who lived nearby, opened a glue factory on the edge of the pond, “amid clover fields and buttonwood trees,” according to Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898, by Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace.

Cooper was a brilliant innovator and inventor in mid-19th century New York. “He also became a pioneer polluter: his factory so fouled the pond’s waters that it had to be drained and filled in 1839,” states Gotham. After that, it was a storage site for streetcars before becoming valuable real estate in an elite neighborhood.

Looking down Park Avenue toward what would have been Sunfish Pond two centuries ago.

Looking down Park Avenue toward what would have been Sunfish Pond two centuries ago.Today, no trace of Sunfish Pond exists anywhere in Manhattan…except in century-old books published by memoirists and historians. But that shouldn’t stop you from standing at Park Avenue South and 31st Street and imaging skaters, fishers, farmers, travelers, and boats ferrying flooded New Yorkers across what was once a placid and peaceful body of water.

[Top image: via Patch; second image: CUNY Graduate Center Collection; third image: Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps; fourth image: NYPL; fifth image: Wikipedia]

December 27, 2020

A cigar box label’s charming New Year’s greeting

When I first saw this Happy New Year greeting, I thought Schumacher & Ettlinger must be a cigar company, with offices on 19th Street and Fourth Avenue, as the image states.

Instead, Schumacher & Ettlinger appear to be a lithography company that produced labels for cigar boxes. Makes sense based on their address; Fourth Avenue (Park Avenue South today, of course) was in the city’s publishing and booksellers’ district…close to what became known as Booksellers’ Row in the 20th century.

The first box label carries the date 1893, and the second one doesn’t appear to have a copyright date. Whenever they were produced, I’m sure the person gifted with a box of cigars for the New Year was quite charmed.

[First image: MCNY 40.70.487; second image: MCNY 40.70.486]

The Lenox Hill carriage houses from a fairytale

There’s nothing like walking through Manhattan during Christmastime and coming upon a row of elfin former carriage houses that look like they were made out of gingerbread and belong in a holiday fairytale.

This “stable row,” as it was known in the late 19th century, is on East 69th Street between Lexington and Third Avenues.

The north side of the street is home to several conjoined carriage houses of different architectural styles and sizes—but all with the traditional arched entryway to fit not just horses but the tall carriages they pulled.

It’s not Lenox Hill’s only row of carriage houses. As Upper Fifth Avenue became the city’s new millionaire mile during the Gilded Age, these new rich New Yorkers built not only resplendent mansions for themselves but decorative stables for their equipage and the workers who took care of them.

These wealthy owners wanted their stables nearby—but not so near that they had to smell and hear their horses. Other stable rows are on East 73rd Street and East 66th Street, and they tend to be east of Lexington Avenue (and thus closer to the tenements and elevated trains, not to mention on the other side of Park Avenue, where the New York Central Railroad had its tracks).

Number 147, the first in the row closest to Lexington, was built by a banker named Herbert Bishop in 1880, according to Christopher Gray a 2014 New York Times article, which delves into the backstories of some of the carriage houses on the block. Bishop lived on Fifth Avenue and 70th Street.

A dye company owner, Adolph Kuttroff, built numbers 153-157 a few years later, according to Gray. John Sloane, of the department family Sloanes (owners of the W.J. Sloane rug and furnishings store on Broadway and 19th Street), parked his vehicle and horses at 159.

“In 1896 came the most remarkable stable on the Upper East Side, when the streetcar millionaire Charles T. Yerkes, whose large house was at 69th and Fifth, had the otherwise little-known Frank Drischler design a three-story-high stable with a broad, double-height arch, gabled front at No. 149,” wrote Gray.

Number 161 has the initials “BB” in the keystone, notes the AIA Guide to New York City. Those initials are for William Bruce-Brown, brother of wealthy sportsman David Loney Bruce-Brown. His obituary says Bruce-Brown resided at 13 East 70th Street, but the Upper East Side Historical District Designation Report from 1981 says he lived in the upper floors of the stable.

George G. Heye, collector and founder of the Museum of the American Indian, owned number 167 (described as “plodding eclectic” by the AIA).

Horses and carriages (and their grooms and drivers) didn’t occupy these stables for much longer. By the teens, they started getting converted into garages for automobiles, then remade into living quarters for people—including Mark Rothko, who lived and had his studio in 157 until his death by suicide in 1970.

Lately, these Victorian, Georgian, and Romanesque stables have changed hands for big money. Art dealer Larry Gagosian sold number 147 for $18 million, according to 6sqfeet.

They’re remodeled, restored, and really, really pricey. But from the street you can imagine them as part of a fairy tale village, or the kind of delightful structures you find in a snow globe—very appropriate for the holiday season.

[Fourth photo: MCNY 1976 2013.3.2.716]

A tender painter’s mysterious death under the el

When George Benjamin Luks’ lifeless body was found in the early morning hours of October 29, 1933 under the gritty elevated train near a doorway at Sixth Avenue and 52nd Street, newspapers reported that this heralded artist and painter died of a heart attack.

George Benjamin Luks by William Glackens, 1899

George Benjamin Luks by William Glackens, 1899“A passing policeman, Patrolman John Ginty of the West 47th Street Station, found him collapsed and summoned an ambulance from Flower Hospital,” stated the Brooklyn Daily Eagle in an article the next day. “The arriving physician found him dead of arterio-sclerosis [sic].”

Supposedly, Luks had left the home he shared with his wife on 28th Street around 6 a.m. and headed uptown to watch the sun rise. This story was confirmed by his brother William, a doctor at the Northern Dispensary on Christopher Street.

Luks’ take on Tammany Hall graft, 1899

Luks’ take on Tammany Hall graft, 1899“He often took long walks in the early hours,” William Luks said, per a 2015 New York Daily News article, “and it was the way he would have wished to die.”

It sounded possible, perhaps. Since he came to New York from Philadelphia in the late 1890s, Luks gained fame first as an illustrator of comics (he took over as the artist for The Yellow Kid) and political cartoons and then for his poetic street scenes, portraits, and urban landscapes.

The jazz clubs and former speakeasies of 52nd Street, 1945

The jazz clubs and former speakeasies of 52nd Street, 1945Luks also gained a reputation as a straight shooter who had no love for the decision makers in the art world, someone who preferred to paint the underdogs of New York’s slums, because “down there people are what they are,” he said.

But the details of the death of a 66-year-old artist known to be a gutsy and “swashbuckling” (as the Eagle called him) drinker and fighter would be much more mysterious.

“Children Throwing Snowballs,” 1906

“Children Throwing Snowballs,” 1906Ira Glackens, son of fellow social realist painter William Glackens and friend of Luks’, supposedly revealed the truth in a 1957 biography of his father.

Luks body was found under the elevated near Sixth Avenue and 52nd Street, as it was originally reported. But heart disease didn’t kill him: a bar fight did.

Under the Sixth Avenue El at about 53rd Street, 1939

Under the Sixth Avenue El at about 53rd Street, 1939 In the biography, Ira Glackens said “[Luks] was knocked cold in a barroom brawl” according to the Daily News. This was in the waning days of Prohibition, when several speakeasies in brownstones lined 52nd Street, aka “Swing Street.”

“The illegal joint could hardly report a drunken row, so Luks—dead or nearly so—probably was carried to the spot where cops found him,” states the Daily News.

George Luks, 1910

George Luks, 1910Is the barroom death story the right one? We’ll likely never know. But it might be the story Luks himself would have preferred—a tough yet tender artist who went down swinging. He’s a favorite of this site; see more of his work here.

[First image: National Portrait Gallery; second image: Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 1933; third image: Wikipedia; fourth image: MCNY X2010.11.6064; fifth image: niceartgallery.com; sixth image: MCNY X2010.7.1.18346; seventh image: Wikipedia]

December 20, 2020

The coal company helped the city survive winter

Stuart Davis was a New York artist of the 20th century best known for his playful Modernist paintings filled with bright colors and geometric shapes. But early in his career, he was influenced by the Ashcan School—and he stuck with the social realist style with this 1912 piece, Consumer Coal Company.

It’s a powerful painting that invites viewers to feel the sharp snap of snow whipping around a low-rise block somewhere in New York City. (I’m guessing Lower Manhattan, see the Federal-style houses with the dormer windows.)

Forced to work in the blustery weather, the men from the coal company shovel a load into a sidewalk coal hole, where it can be transferred to the furnace to keep residents from freezing to death.

It probably wasn’t Davis’ intention when he painted this scene to provide insight into how life was lived in New York in 1912. But the painting immortalizes the role the coal companies played in New York winters—when Gotham was still largely dependent on coal-burning furnaces (not to mention horse-pulled wagons).

A Christmas feast at Midtown’s new Hotel Pabst

Never heard of the Hotel Pabst? You’re not alone. The nine-story tower with a steel skeleton swathed in limestone only existed from 1899 to 1902—built on the slender triangle formed by Broadway, Seventh Avenue, and 42nd Street at Longacre Square.

Hotel Pabst in Longacre Square

Hotel Pabst in Longacre SquareRun by the Pabst Brewing Company as part of a short-term effort to acquire hotels, the elegant hostelry at the upper reaches of the city’s theater district and lobster palaces was replaced by the New York Times‘ headquarters in 1904 (and Longacre Square became Times Square).

The spicy cover of the Hotel Pabst’s Christmas menu

The spicy cover of the Hotel Pabst’s Christmas menuThe Pabst didn’t last, and no one alive today would remember it. But it needs to be noted that on December 25, 1900, the hotel sure cooked up a spectacular Christmas dinner.

The eye-popping Christmas dinner menu has been preserved by the New York Public Library in their Buttolph Collection of Menus. Between the carte de jour oyster offerings to the 20-plus desserts (plum pudding! Cream puffs!) are a dozen or so courses that must have taken an army of chefs to prepare.

Many of the dishes are the typical heavy fare of a hotel menu in New York of the era: terrapin a la Maryland, quail, stuffed turkey, filet of sole, prime beef, and lamb chops.

There’s a fair number of items borrowed from French menus, which makes sense, as French cuisine was seen as the most elegant at the time.

Some of the dishes are completely foreign to contemporary American tastes, however. Cold game pie, Philadelphia squabs, and reed ducks, anyone?

One thing stands out, though: Christmas dinner at a hotel in 1900 was certainly a feast. By the time you finished your Nesselrode pudding and revived yourself with your Turkish coffee, buttons must have been popping off your clothes!

[Top photo: MCNY 93.1.1.6427; menu: NYPL Buttolph Collection of Menus]