Esther Crain's Blog, page 49

June 6, 2022

The sweet side of a New York tenement roof in the summer

If you’ve never done it, laying out on a tenement roof on a hot summer day might sound very unappealing. It’s sweaty and sticky, there’s barely a breeze, and you can feel as if you’re on view, within the prying eyes of neighbors or strangers in nearby buildings.

But the way John Sloan depicts it in his 1941 etching “Sunbathers on the Roof,” spending the day on tar beach means being in your own private paradise. The low wall around the rooftop can double as a moat keeping out interlopers; sharing a blanket like this couple does adds to the sensuality and intimacy of reclining together in bathing suits.

These two have things to read, suntans to work on, and an attention-seeking cat (a pet or building stray?) to amuse them. The magnificent city they’ve turned their backs to may as well not even exist; they already have everything they need.

[Smithsonian American Art Museum]

Looking for remnants of Paisley Place, a lost row of back houses in Chelsea

Like many downtown neighborhoods, Chelsea has its share of back houses—a second smaller house or former carriage house built behind a main home and accessed only by an often hidden alleyway.

Now imagine not just one back house but an entire row of them forming a community where a group of people lived and worked for decades, almost locked within a city block. That’s kind of the story of Paisley Place, which got it start after yellow fever hit New York City in October 1822.

With an epidemic raging, city residents fled. “The banker closed his doors; the merchant packed his goods; and churches no longer echoed words of divine truth,” stated Valentine’s Manuel of 1863. “Many hundreds of citizens abandoned their homes and accustomed occupations, that they might seek safety beyond the reach of pestilence, putting their trust in broad rivers and green fields.”

A good number of these fleeing residents relocated to the village of Greenwich, putting down roots there and transforming it into an urban part of the city within a few decades.

Southampton Road making its way through Chelsea on the John Randel survey map from 1811

Southampton Road making its way through Chelsea on the John Randel survey map from 1811One group of immigrant artisans—Scottish-born weavers who carved out a niche by supplying New York with hand-woven linens—went a little farther north. These tradesmen and their families set up a new community in today’s Chelsea off a small country lane called Southampton Road. (above map).

“A convenient nook by the side of this quiet lane was chosen by a considerable number of Scotch weavers as their place of retirement from the impending dangers,” according to Valentine’s. “They erected their modest dwellings in a row, set up their frames, spread their webs…and gave their new home the name ‘Paisley Place.'”

This 1857-1862 street map shows a row of three houses in the middle of the block marked “weavers.”

This 1857-1862 street map shows a row of three houses in the middle of the block marked “weavers.”Southampton Road, which once wound its way from about West 14th Street and Eighth Avenue to West 21st Street and Sixth Avenue, soon ceased to exist as Chelsea urbanized and conformed to the street grid. The houses of Paisley Place then became “buried in the heart of the block between 16th and 17th Streets and Sixth and Seventh Avenues,” wrote the Evening World.

Through the decades, the weavers carried out their trade. Paisley Place consisted of “a double row of rear wooden houses entered by alleys at 115-117 West 16th Street and 112-114 West 17th Street,” per The Historical Guide to the City of New York, published in 1905.

A similar map also from 1857-1862 marks another back house with “weaver”

A similar map also from 1857-1862 marks another back house with “weaver”More is known about their houses than the weavers themselves. “The little colony mingled only slightly with the scores of other nationalities of early New York,” stated another Evening World piece.

By the 1860s, the weavers became something of a curiosity, the subject of newspaper articles and magazine sketches. After 1900 the people of Paisley Place were gone; they either died or moved on when their hand-weaving skills were no longer needed in the era of industrialization.

Their homes hidden inside a modern city block held on a little longer. “The Scotch weavers are gone, but the houses which they built still hold their long accustomed place on the line of the vanished Southampton Road,” stated a Brooklyn Standard Union article from 1902.

17th Street between Sixth and Seventh Avenues

17th Street between Sixth and Seventh AvenuesThe writer of the Standard Union article noted that two remaining wooden houses had a “quaint picturesqueness [that] was of a sort to warm the heart of the antiquarian.”

Today, 17th Street doesn’t seem to carry any traces of this former community, and no remnants remain of the wood houses that would be in the middle of this tightly packed block. This antiquarian, however, wishes that something of their lives was left behind.

[Top image: Valentine’s Manual, NYPL; second image: John Randel survey map; third and fourth images: NYPL]

May 30, 2022

This is how New York celebrated Decoration Day in 1917

“Not since 1898 have the Decoration Day parades and ceremonies had the significance which will emphasize them to-day,” wrote The Sun on May 30, 1917. “The city will not only pay tribute to the heroes of the past, but the marching columns of youths and veterans will help stimulate the country to the highest endeavor to gain victory in the world war.”

“Twenty thousand uniformed men will march up Riverside Drive, while 50,000 schoolboys will parade up Fifth Avenue,” the newspaper stated on the front page. “The two parades will start at 9 o’clock in the morning. The Grand Army of the Republic and its accompanied divisions will leave Broadway and 72nd Street, march west to Riverside Drive, then north to Grant’s Tomb, and will be reviewed on the way at the Soldiers and Sailors Monument at 86th Street.”

[Photo: LOC/Bain Collection]

The last “vulgar” survivor of a row of four Fifth Avenue mansions

First there were four. Built in 1901 by brothers William and Thomas Hall as speculation developments, the row of mansions from 1006-1009 Fifth Avenue each featured six stories of eclectic Beaux Arts details and a premier address in the late Gilded Age city’s millionaire colony.

Today only one remains. Number 1009, on the corner of 82nd Street across from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, stands like a long slender ghost of New York at the turn of the last century. It’s one of a handful of row house mansions left on upper Fifth Avenue.

As much as New Yorkers today admire Gilded Age mansions like Number 1009, with its fairy tale balconies, mansard roof, romantic bays, and fanciful facade carvings, not everyone back then was a fan.

Critic Montgomery Schulyer, writing in Architectural Record in October 1901, singled out Number 1009’s “sheet-metal cornice painted to imitate stone,” according to Christopher Gray in a 1995 New York Times article.

“We hold these truths to be self-evident,” Schuyler wrote, via Gray’s article, “that, when a man goes into ‘six figures’ for his dwelling house, he ought not to make its upperworks of sheet metal. That is a cheap pretense which nothing can distinguish from vulgarity.”

1006-1009 Fifth Avenue in 1925

1006-1009 Fifth Avenue in 1925The criticism didn’t put a dent in sales; the Hall brothers sold all four mansions. Number 1006 went to bank president William Gelshenen and his wife, Katherine, according to the 1977 Landmarks Preservation Commission report for the Metropolitan Museum Historic District. Henry and Kate Timmerman, professions unknown, purchased Number 1007, while a William Augustus and Sarah Hall purchased Number 1008.

1006-1009 in 1940

1006-1009 in 1940Number 1009 went to major money: Mr. and Mrs. Benjamin Duke. Duke was one of the brothers who ran the American Tobacco Company and funded Duke University. The Dukes didn’t stay very long, moving to the Plaza Hotel in 1909, wrote Gray.

The mansions, upper right, in a 1925 postcard

The mansions, upper right, in a 1925 postcardBenjamin Duke’s brother James and his family lived there next, until James Duke relocated to his own new mansion on Fifth Avenue and 78th Street. Incredibly, a succession of Duke family members lived in the house at one time or another through the 1970s, when it received landmark designation.

Numbers 1006, 1007, and 1008 weren’t so lucky. “The two houses at numbers 1006 and 1007 were demolished in 1972, amid strong protest, at a time when the Landmarks Preservation Commission was unable to hold public hearings and landmark proposals,” according to the LPC report. Meanwhile, “the much-altered house at number 1008 was demolished in February [1977].”

The entrance on 82nd Street

The entrance on 82nd StreetA 22-story building, 1001 Fifth Avenue, replaced all three.

Number 1009 Fifth Avenue, known today as the Duke-Semans House or the Benjamin N. Duke House, has had a few colorful owners since the turn of the 21st century. In 2006, a billionaire named Tamir Sapir bought the house for a reported $40 million, according to Forbes. In 2010, he flipped it for $44 million to Mexican billionaire Carlos Slim.

Slim put the townhouse on the market in 2015 for $80 million. Some interior shots made it online, though it’s unclear if it sold or is still up for grabs.

[Third image: NYPL; fourth image: NYC Department of Records and Information Services; fifth image: MCNY x2011.34.3703]

May 29, 2022

The seafaring symbols on a Turtle Bay church’s stained glass window

Walk down East 52nd Street between Second and Third Avenues on a bright day, and you’ll probably miss it.

But some nights when the interior lights are on, the spectacular stained glass window in the middle of this five-story church on East 52nd Street illuminates the street below with startling color and beauty.

The window is the visual centerpiece of the Norwegian Seamen’s Church—two former brownstones joined together on a mostly residential block offering Norwegian sailors, students, ex-pats, and visitors from all backgrounds a place of worship as well as a cultural center and coffee spot.

The church has been at the site since 1992, hidden amid a row of low-rise walkups. But its roots go back to the 1870s, when the first Norwegian Seamen’s Church opened on Pioneer Street in Red Hook. Fifty years later, the church moved to Clinton Street and First Place in Carroll Gardens, closer to the Norwegian community in Bay Ridge.

As the community dispersed later in the 20th century, the church made another move, this time to Manhattan.

The details painted on the compass-like window are a visual delight, and I’ll try my hand at interpreting these symbols. In the center is a seagull, flying high over the earth’s horizon approaching the heavens, which are marked by a cross.

In 2018, a church pastor told the Turtle Bay Association website that the seagull, “follows ships at sea, so this is appropriate because Norwegians love to travel and wander around cities like New York.”

On the left is a lamb with a staff and halo—the lamb of God. A Viking ship is painted on the bottom, and on the right, it looks like another bird, perhaps signifying the Holy Spirit. The image at the top is hard to make out, but it looks like it symbolizes the power of God.

May 23, 2022

This holdout brownstone is a monument to the 1980s tenant who refused to leave

These days, the traffic-packed intersection at Lexington Avenue and 60th Street is a modern tower mecca of street-level retail shops topped by floor after floor of office space and luxury residences.

But steps away from this busy urban crossroads is a curious anachronism: a four-story brownstone. Number 134 East 60th Street has been stripped of its entrance and 19th century detailing. It sits forlorn, dark, and boxy, attached to the 31-story tower behind it and to a Sephora next door.

There’s no longer a door or first and second floor windows, so it’s unlikely anyone lives in this walkup, which used to be part of a pretty block of brownstones built in 1865. So how did it escape demolition—and why is it still here?

Think of it as a brick and mortar memorial to a woman named Jean Herman, who almost 40 years ago refused to cede her small apartment on the fourth floor to the developers of the tower.

The story begins in the early 1980s. Herman was a freelance public relations specialist who had a longtime rent-stabilized lease of $168 per month for her two-room apartment here, according to the New York Times. She liked living in the neighborhood, she told the Times in another article, and she decorated her small home with window boxes of petunias and geraniums, per an AP story.

60th Street and Lexington Avenue in 1912, with rows of 1860s brownstones

60th Street and Lexington Avenue in 1912, with rows of 1860s brownstonesThen in 1981, a real-estate development company called Cohen Brothers “bought her building and every other on Lexington Avenue between 59th and 60th Street, across from Bloomingdale’s department store, with plans to demolish them all,” stated the AP piece.

Other tenants were evicted or bought out. Herman stayed put, and because her apartment was rent stabilized, she couldn’t be forced to leave. So the developers “offered to find her another apartment and work out an arrangement in which they would pay her rent, plus a stipend,” wrote the Times.

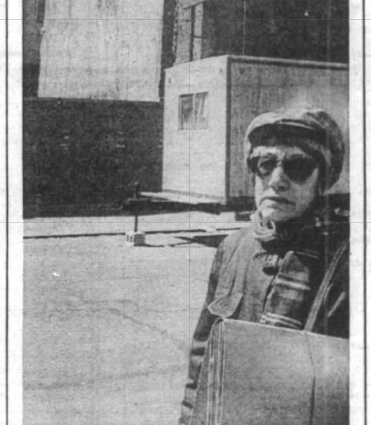

Jean Herman in the Daily News, 1986

Jean Herman in the Daily News, 1986Herman was shown 25 apartments in the general neighborhood, but none of them worked for her because they were not rent-stabilized. She told the Times, “if I move this time, I don’t intend to do it again.” Reports came out that she was offered six figures, even a million dollars to give up her home, but Herman insisted these numbers weren’t accurate.

By 1986, Herman was the only tenant left in her brownstone. After exhausting all avenues for getting her out of the building, the developers gave up and begin construction on the tower. When it was completed, the tower opened with Herman still living in the brownstone.

Herman didn’t occupied her apartment for much longer; she died of cancer in 1992. “Her vacancy last month came too late for the Cohens, who remain bitter over what they regard as Miss Herman’s utter folly,” the AP article stated.

To many New Yorkers, however, Herman is something of a heroine, unafraid to stand up to developers and defend herself under the threat of losing the home she was happy with. Her holdout brownstone makes a very appropriate monument.

[Third image: New-York Historical Society; fourth image: Tom Monaster/New York Daily News March 23, 1986]

May 22, 2022

Manhattan’s most ornate early apartment house comes back into view

In 1907, the developers behind Alwyn Court announced their plans to build this 12-story luxury apartment house on the corner of Seventh Avenue and 58th Street. “It will have ornamental facades of limestone, with terra cotta trimmings,” the New-York Tribune dutifully reported.

That ho-hum description of the facade hardly did the Alwyn justice. When the aristocratic edifice opened to well-to-do tenants two years later—advertising itself as a place of “city homes for people with country houses”—the limestone and terra cotta facade proved to be one of the most ornate ever unveiled.

Alwyn Court’s exterior is an “intricate stone tapestry” of baroque scrolls, floral motifs, grotesques, angels, and crowned salamanders. The salamanders represent Francois I, the French king during the Renaissance whose style the building emulates. (The Alwyn is one of two New York buildings that feature salamanders on the facade, both by the same architects, Harde & Short.)

“This is the finest building of its type in New York City,” states the 1966 Landmarks Preservation Commission report, which designates Alwyn Court a city landmark.

Most luxury apartment buildings of the era only used terra cotta on the base of the facade and thus didn’t have excessive room or ornamentation, the LPC report explains. “Here at Alwyn Court, instead of limiting the decoration, the architects went to the other extreme, leaving hardly any surface undecorated,” states the report.

A lot has changed at the Alwyn since 1909. Originally the building had two apartments per floor with at least 14 rooms and five baths each, along with personal wine cellars for tenants and other exclusive amenities. (Remember, apartment living for the rich was still a new concept, so they tried everything to lure in residents.)

But that layout was eventually altered in favor of more apartments per floor that had fewer rooms. In the 1930s, the lobby was redone, then remade again in 1982 when an air shaft was turned into a central atrium. After a protracted battle with longtime tenants (including many senior citizens living in rent controlled units), Alwyn Court went co-op in the early 1980s.

By Berenice Abbott in 1936

By Berenice Abbott in 1936 Now, following a long stint behind construction scaffolding, Alwyn Court’s filigreed facade is fully on view. It looks as beautiful as it did in 1936, when Beatrice Abbott photographed a portion of the building for her book, Changing New York.

[Last photo: Sotheby’s]

May 19, 2022

A painter’s mystery scene on the Sixth Avenue elevated after midnight

Elevated trains were the fastest mode of mass transit in the late 19th century. Lurching and groaning high above the sidewalks along almost all of New York’s avenues, they whisked people to work, to school, to the theater, to Central Park, to department store shopping—all for a nickel per ride.

At night, the elevated invited intrigue. Everett Shinn, former newspaper illustrator best known as a member of the Ashcan School of social realism painting, captures a moment at one end of a poorly lit all-male car in his 1899 work, “Sixth Avenue Elevated After Midnight.”

The Manhattan country estate houses of old New York’s forgotten families

The significance of their names has been (mostly) forgotten, their spacious wood frame houses in the sparsely populated countryside of Gotham long dismantled, carted away, and paved over.

The Riker estate, in 1866

The Riker estate, in 1866But the wealthy New Yorkers who purchased vast parcels of land and built these lovely country homes (surrounded by charming picket fences, according to the illustrations left behind) in the late 18th or early 19th centuries deserve some recognition.

These “show places,” and one source called them, dotted much of Manhattan in the era when the city barely extended past 14th Street. The families who owned them likely lived much of the year downtown. But when summer brought stifling heat and filthy streets (and disease outbreaks), they escaped to their estates by boat or via one of the few roads in the upper reaches of the island.

Arch Brook on the Riker estate grounds, 1869

Arch Brook on the Riker estate grounds, 1869The estate house in the top image belongs to a familiar name: It’s the country home of one member of the Riker family, circa 1866. Before their name became synonymous with a jail and an island in the East River, the Rikers were a well-known old money clan. Abraham Ryeken, who sailed to New Amsterdam from the Netherlands and owned a home on Broad Street, was the patriarch.

The descendent who lived in this house on today’s 75th Street and the East River was Richard Riker, born in 1773. He held a number of positions in New York including district attorney. Known for his “polished manner and social prominence,” he counted Alexander Hamilton as a friend. Riker died in 1842, and his funeral commenced in the estate house, according to the New-York Tribune. Could that be his widow in the illustration?

Cargle house, 1868

Cargle house, 1868On the other side of Manhattan stood this pretty yellow house (above) with the gable roof, long side porch, and four chimneys. It was the estate home on the Cargle family at 60th Street and Tenth Avenue. It’s modest by 19th century standards, but far larger than any town house or early brownstone. The land might have even extended all the way to the Hudson River.

Who were the Cargles? This name is a mystery. Newspaper archives mention a Dr. Cargle, but so far the trail is cold. The image dates to 1868, and the paved road has a sidewalk and gas lamp. Imagine the cool river breezes on a warm summer night!

Provoost house, 1858

Provoost house, 1858The Cargles lived across Manhattan from David Provoost and his family. The Provoost country residence (above) was on 57th Street and the East River, just blocks north of another fabled estate house of a notable family—that of the Beekmans.

David Provoost, or Provost, was the son of a New Amsterdam burgher who became a merchant and then mayor of New York from 1699 to 1700. Provost Street in Brooklyn and Provost Avenue in the Bronx are named for him or perhaps a family descendent. Who built the house, so grand that it qualifies as a true mansion?

Henry Delafield mansion, built in the 1830s and pictured in 1862

Henry Delafield mansion, built in the 1830s and pictured in 1862The Delafield house (above) is another mansion that must have been lovely and cool thanks to the East River nearby. Located on today’s East 77th Street and York Avenue, it was the home of Henry Delafield, son of John Delafield, who arrived in New York from England in 1783. Delafield became one of the “merchant princes” of New York, according to 1912 New York Times article.

Henry Delafield also became a merchant and founded a shipping firm with his brother. His house was described by the Times as “one of the show palaces among the splendid country residences on the East Side north of 59th Street. He died in 1875. “The latter years of his life were spent pleasantly on his fine country estate overlooking the East River,” the Times wrote. Fine, indeed!

[Images: NYPL Digital Collection]

May 18, 2022

Updated info on Talks and Tours From Ephemeral New York!

I’m excited to let everyone know that two more dates have been added in June for Ephemeral New York’s Gilded Age Mansions and Monuments walking tour. On the tour, we step back to the avenue’s 18th century roots in the Bloomingdale section of Manhattan, and then revisit it in the Gilded Age, when Riverside Drive was set to become New York’s newest “millionaire colony.”

The first tour is on Sunday, June 5 from 1-3 pm; tickets can be purchased here. The second tour is scheduled for Sunday, June 19 from 1-3 pm; tickets available here. These tours are in conjunction with the New York Adventure Club.

I also want to give an update on the Tea Talk originally scheduled at the Salmagundi Club for Thursday May 19. Because of the uptick in Covid cases in New York City, the talk has been postponed until fall.

[Images: NYPL]