Esther Crain's Blog, page 47

July 11, 2022

Where life in New York City was lived “on the steps”

Between the cramped spaces, poor ventilation, and shadowy hallways, life inside a New York City tenement could be hard to bear, especially in warm weather. For relief, people headed to their outside steps: men buried themselves in the newspaper, women rocked babies, small kids played games. In a pre-air conditioned city, front stoops were lively places.

It’s unclear exactly where Ashcan painter George Luks captured this scene outside a rundown building. But he appropriately named the painting “On the Steps”—where much of life played out in New York’s tenement districts.

This 1905 power plant is one of the West Side’s most beautiful buildings

With construction of the city’s first subway system underway, the Interborough Rapid Transit Company needed to build a massive generating plant that would create enough electricity to run the new lines.

Industrial buildings aren’t always designed with beauty in mind. But this was the early 1900s, the era of the City Beautiful movement. City Beautiful held that urban buildings should be architecturally inspiring and promote civic pride rather than be plain and utilitarian.

So while a team of pioneering engineers designed the interior workings of the building, IRT officials gave the responsibility of the exterior to Stanford White—the celebrated (and scandalous) architect whose brilliant artistic and architectural aesthetic was on display all over New York, from the Washington Square Arch to Madison Square Garden to numerous mansions, among other noteworthy structures.

White’s creation, known as the IRT Powerhouse, was completed in 1905. Spanning the entire block from 11th to 12th Avenue at the far western end of 59th Street, it epitomized the City Beautiful movement and looked more like a museum or concert hall than a coal-fed power plant.

Its location gives it away as an industrial structure. The Powerhouse opened at the nexus of two rough-edged tenement enclaves, Hell’s Kitchen to the south and the former San Juan Hill neighborhood to the north. The area was open and gritty, blocks away from the cattle pens and abattoirs of the West Side stockyards but with access to the river.

“Executed in the Beaux-Arts style and drawing upon Renaissance prototypes, it is the embodiment of the aesthetic ideas of the City Beautiful movement, which held that public improvements could beautify American industrial cities,” stated the Landmarks Preservation Commission in 2017.

“White’s design masterfully concealed the boiler house and generating station with elegant, unified façades cloaked in Milford granite, Roman brick and creamy terra cotta with neoclassical ornament.”

Sketch of the completed IRT Powerhouse, 1904

Sketch of the completed IRT Powerhouse, 1904Christopher Gray, writing in the New York Times in 1991, had this to say: “Giant arched windows march down each side, separated by huge pilasters and topped by an attic story and, originally, an elaborate projecting cornice. Some of the detailing is patterned after electrical designs but most is like a stylebook of classical patterns: delicate wreaths, sharp palmette leaves, swags and the like—an esthetic anomaly in this industrial area.”

This commemoration of industrial might and power has undergone some changes in the ensuing years. The cornice was stripped, and only one of the original smokestacks survives. In the last decade or so, the formerly gritty neighborhood has become the site of modern apartment towers that offer a cool contrast to the warmth of the power plant’s brick and terra cotta.

When the IRT went under three decades after launching the first subway lines, the city took the plant. “The city took possession of the building in the early 1930’s when it bought the IRT lines, and Con Ed bought the station from the city in 1957,” stated Michael Pollak in the New York Times‘ FYI column in 2006.

Instead of electricity, the power plant now creates steam for Manhattan buildings. It’s also an official landmark as of 2017, “a monument to the engineers and architects who planned and built New York City’s first successful subway system,” per the LPC.

[Fourth image: Wikipedia]

July 10, 2022

What remains of the horses that powered Gilded Age New York City

If you could time-travel back to the 1880s, you’d notice all the horses first. (Second would be all the horse manure, but that’s another story.) At the time, an estimated 170,000 horses pulled the streetcars, delivery wagons, and carriages that allowed New Yorkers to get around the metropolis.

Cedarhurst Stables, 83rd Street between Columbus and Amsterdam Avenues

Cedarhurst Stables, 83rd Street between Columbus and Amsterdam AvenuesBut the era of horse-powered transportation was coming to a close. Elevated trains were whisking passengers across Manhattan and Brooklyn; cable cars began replacing some horse-drawn streetcar lines. The subway arrived in 1904, and by the 1910s, the motor car (or “devil wagon,” as haters called it) sidelined horses from Gotham’s streets.

Considering that much of New York’s infrastructure was built when horsepower ruled the roads, surprisingly little of the equine era remains.

The carriage roads of Riverside Drive are still with us, as are horse water fountains in some city parks. Manhole covers with patterns to prevent horse hoofs from skidding exist as well. Stable blocks and mews where the wealthy once parked their broughams have been converted to (pricey) homes for humans.

The former stable at 49 Market Street

The former stable at 49 Market Street Yet sometimes you see an ornamental ghost from the horse-powered past. Look up at 157 West 83rd Street to the red brick car garage—and a handsome horse head on the facade will delight you.

The garage used to be Cedarhurst Boarding Stables. Cedarhurst first appeared in city directories in 1892, according to Walter Grutchfield. Just 16 years later, the four-story stable became Cedarhurst Garage, for automobiles.

Another decorative horse head can graces 49 Market Street on the Lower East Side. The site is a lot less illustrious than the Cedarhurst, but it too was home to a stable in the Gilded Age—in 1894, according to Bowery Boogie.

And like the Cedarhurst, the stable didn’t last long, as the automobile era took hold. By 1915, “the two-story brick structure as we know it today was already in place,” per Bowery Boogie. The horse head—complete with bridle—remains high above this old New York street.

July 9, 2022

July Walking Tours of Gilded Age Riverside Drive With Ephemeral New York!

During July, I’ll be leading three delightful and insightful walking tours through the New York Adventure Club, “Exploring the Gilded Age Mansion and Memorials of Riverside Drive.”

The tours start at 83rd Street and ends at 107th Street. In between we’ll walk up Riverside and delve into the history of this beautiful avenue born in the Gilded Age, which became a second “mansion row” and was set to rival Fifth Avenue as the city’s “millionaire colony.” The tours will explore the mansions and monuments that still survive as well as the incredible houses lost to the wrecking ball.

A few tickets remain for the Riverside Drive tour for Sunday, July 10—tickets can be purchased here.

Tickets for Sunday, July 17 can be bought here, and tickets for Sunday, July 31 at this link. All are welcome; hope to see a great turnout on any of these lovely summer days!

July 4, 2022

Join Ephemeral New York for a free presentation on women of the Gilded Age!

The Gilded Age was a captivating era of growth, greed, and deep cultural changes that set into motion the way we live today. It was a time when men and women typically occupied vastly different spheres: men in the outside world of business and industry, women as the center of home, family, and society.

But that doesn’t mean women didn’t have power and influence. Join me on Thursday, July 7 from 1-2 p.m. as I moderate a free Zoom presentation that features stories of women during the Gilded Age from Laura Thompson, author of Heiresses: The Lives of the Million Dollar Babies, and Betsy Prioleau, author of Diamonds and Deadlines: A Tale of Greed, Deceit, and a Female Tycoon in the Gilded Age.

“Women in the Gilded Age: Two Authors’ Insights” is part of American Inspiration, the best-selling author series by American Ancestors. Among the Gilded Age women we’ll explore are Consuelo Vanderbilt, daughter of social climbing, new money doyenne Alva Vanderbilt, and Mrs. Frank Leslie, who took over her husband’s publishing empire and influenced millions of readers.

Follow this link for more information and to sign up. Audience questions will be addressed, and both authors are wonderful storytellers. The event should be informative as well as a lot of fun. Everyone is welcome!

July 3, 2022

The misery of trying to sleep during the New York City heatwave of 1882

When the city is in the grips of a punishing heatwave, and you live in a tenement with almost no ventilation (let alone a cross breeze), you do what you can to get some rest.

For the roughly two-thirds of New Yorkers who lived in old-law tenement buildings in 1882, that meant resorting to dangerous options like climbing out on the flimsy roof, hanging out the window sill, or even catching rest on the back of an open wagon.

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, 1882

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, 1882In 1882, an artist working for Frank Leslie’s illustrated Newspaper captured this scene of East Side misery. Turns out there was a terrible heat wave in July 1882, and newspapers covered the toll it took, reporting the daily count of people who suffered “heat prostration” and either died or were brought to hospitals.

“The atmosphere continued to retain its scorching quality even after darkness came on, and those who fancied that nightfall would bring some relief were disappointed,” wrote The New York Times on July 12.

[Illustration: Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper/LOC]

A once-elegant Lower East Side house where a gruesome sport played out

The Federal-style brick house at 47-49 Madison Street has been battered by the elements for more than two centuries.

But imagine what it must have looked like after it was built in the early 1800s. In post-colonial, population-booming Gotham, it was likely a comfortable home for a single family on a respectable street—formerly part of the Rutgers farm on today’s Lower East Side.

Perhaps the commercial space on the ground floor was part of the original layout, a storefront for a merchant or artisan whose family occupied private quarters on the second and third floors, with bedrooms behind those dormer windows.

But distinguished streets in New York City have a way of becoming disreputable pretty quickly. Already looked down upon because of a typhus outbreak there in 1820, Madison Street (known until 1826 as Bancker Street) “turned less desirable,” states the 2012 guide book, Lower East Side.

Madison Street’s slide continued through the next decades. Not only was it near the rough and ready East River waterfront, where boardinghouses and dive bars for sailors abounded, but it was dangerously close to the Five Points, the notorious slum district a few blocks north.

By the middle of the 19th century, 47-49 Madison’s days as a family home were long over. At that point, the house had transformed into a venue for a kind of gruesome entertainment contemporary New Yorkers generally have a hard time understanding: rat baiting.

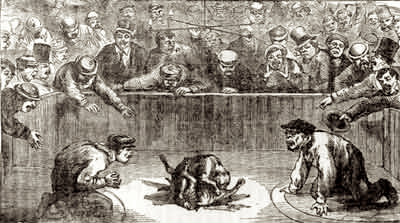

Rat-Baiting at “Sportsman’s Amphitheater”

Rat-Baiting at “Sportsman’s Amphitheater”“Rat killing was the premiere gentlemen’s betting sport of the mid-19th century,” stated Atlas Obscura in a 2014 post. “The boys of the Bowery were paid 5-10 cents for each rat collected, and spectators crowded into the hall to bet on how many rats the fighting dogs could kill in a given time span.”

In the early 1850s, the rat pit at 47-49 Madison was called “J. Marriott’s Sportsman’s Hall.” Marriott’s wasn’t the only rat-fighting venue in New York City at the time. Not far away at 273 Water Street, a man named Kit Burns entertained crowds by pitting rats against terriers.

47-49 Madison Street in 1939-1941

47-49 Madison Street in 1939-1941“Behind closed doors all over the area, the debauched pastime thrived, with politicians and well-to-do society members coming downtown to gamble amid the saloons and slums of the Five Points,” stated Atlas Obscura.

After Marriott departed, 47-49 Madison Street had a new owner. Harry Jennings was an Englishman who continued staging rat fights for sport. In a 1910 Brooklyn Times Union article recalling Jennings, a man who was his neighbor across Madison Street wrote: “Boys at that time could sell all the rats they could catch….He would put a certain number in the pit, and the dog that could kill the most in a given time was considered the winner.”

Kit Burns’ rat pit on Water Street

Kit Burns’ rat pit on Water Street“I well remember the racket they used to make—men hollering, dogs barking, and rats squeaking.”

Jennings ended up doing time for robbery. When he came back to New York, the sport of rat-baiting was losing its appeal. He left Madison Street and became a legitimate rat killer, hired by fancy hotels and businesses to catch the innumerable rats that made their homes in high-class hostelries and stores.

“He made lots of money at his queer trade,” wrote The Evening World in an announcement of his death in 1891.

As for 47-49 Madison Street, the little house was occupied by an undertaker. In the 1960s, a discount store called Johns moved in. Today it’s a prayer hall, according to Atlas Obscura.

[Third image: Wikipedia; fourth image: New York City Department of Records and Information Services; fifth image: Wikipedia]

June 27, 2022

The bookseller at the door in 1940s Greenwich Village

The photo, by Berenice Abbott, invites mystery. “Hacker Book Store, Bleecker Street, New York” is the title, dated 1945. Who is the pensive man at the door—and where on Bleecker Street is this?

The answer to the latter question is 381 Bleecker Street, near Perry Street in the West Village. As for the pensive man, it’s likely Seymour Hacker, a bookseller well-known enough in a more literate New York City that he merited a detailed obituary in the New York Times in 2000 when he died at age 83.

“A small, bright-eyed man fluent in four languages, Mr. Hacker was one of the last booksellers to learn his trade from the bookmen whose stores and stands once lined Fourth Avenue between Astor Place and 14th Street,” wrote Roberta Smith. “Born on the Lower East Side in 1917, he grew up in the Bronx and began haunting Fourth Avenue when he was 12.”

Hacker opened his first bookstore in 1937. “Noting that fine art books were in especially great demand, he opened Hacker Art Books at 381 Bleecker Street in Greenwich Village in 1946, moving uptown in 1948. Customers included Delmore Schwartz, Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning and Mr. Hacker’s friend Zero Mostel,” stated Smith. “Uptown” took Hacker to 57th Street.

Another mystery: why Abbott chose Hacker and his store as the subject for one of her photographs.

[Photo: MCNY: 2014.90.1]

Three holdout brownstones hiding in the Diamond District

For a block devoted to the jewelry trade, 47th Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues has business bustle and energy…but not much sparkle.

Marked by two oversized diamond-shaped lights (below) and some colorful signage above some storefronts, the buildings lining the block dubbed the Diamond District seem drab—not unlike neighboring blocks with a similar mix of old brownstones and commercial loft buildings in the shadows of modern office towers.

It’s curious how this unlovely stretch of Midtown—a tidy townhouse and brownstone street in the Gilded Age—ended up as the modern-day Diamond District. Since the mid-19th century, New York’s jewelry district was firmly centered on Maiden Lane, according to Barak Richman in a 2020 article in The Conversation.

The reason for the move came down to the increasingly high rents for Maiden Lane’s old building stock. “When wealthier banks started driving up downtown rents in the 1920s, diamond businesses started moving uptown to 47th Street,” wrote Richman.

1-11 West 47th Street in 1913

1-11 West 47th Street in 1913One real-estate developer saw an opportunity. In 1923, “Fenimore C. Goode, a broker, promoted construction of a new building at 20 West 47th Street specifically to tempt the Maiden Lane firms,” wrote Christopher Gray in a 2008 New York Times column.

Diamond and jewelry concerns began relocating to Number 20, as well as new buildings that followed at 40 West 47th Street and One West 47th Street, stated Gray. Within a few years, Gray continued, “The Real Estate Record and Guide reported that the 47th Street block “has almost overnight become New York’s new Maiden Lane.”

75 West 47th Street

75 West 47th StreetTo make room for the trade, new construction came in, replacing the townhouses and brownstones. Some dark and forlorn low-rise holdouts still survive in the Diamond District though, hiding between bigger buildings and behind store signs.

28 West 47th Street

28 West 47th StreetYou can easily imagine 75 West 47th Street (above) as one in a row of handsome 19th century brownstones, likely with a high stoop leading to a parlor floor. Only the top two floors are visible now, grimy with age, along with the signature cornice.

28 West 47th Street, 1939-1941

28 West 47th Street, 1939-1941Its neighbors underwent major makeovers, but 28 West 47th Street has remained the same—just as it looked in this 1939-1941 tax photo, above.

The prettiest holdout building might be this sweet walkup, below, at 33 West 47th Street. No cornice remains, a window is blocked by an air conditioner, and a two-story storefront obscures the bottom two floors. But imagine the romance that balcony might have inspired!

33 West 47th Street

33 West 47th Street[Third image: NYPL Digital Collection; fourth image: New-York Historical Society/Robert L. Bracklow Photograph Collection; seventh image: NYC Department of Records and Information Services]

This magical Coney Island building was home to an early New York restaurant chain

It’s a Spanish Colonial–style festival of terra cotta: an imaginative building with a beach-white facade, enormous arched entryways, and colorful images of seashells, fish, seaweed, ships, and Neptune himself looking out over the Coney Island boardwalk.

With such rich ornamentation and design, you’d think the dreamlike structure at West 21st Street served as a movie theater, a casino, perhaps an arcade featuring some of the outrageous exhibits Coney Island was famous for in the early 20th century.

But the building was actually home to a pioneering restaurant called Childs—one of New York’s first restaurant chains and a forerunner of the kind of clean, reliable, and inexpensive eateries found all over the city today. (Here’s an early menu.)

To get a sense of how integral Childs was to Gotham’s restaurant culture, go back to New York City after the Civil War, when dining in a restaurant (rather than cooking meals at home, or eating at a tavern if you were traveling) was something reserved only for the wealthy.

As the Gilded Age progressed, restaurants began opening to middle class and working-class residents as well. These were the army of clerks, shop girls, factory workers, and others who powered the industrialized city. But not all of the new lunch counters and saloons they patronized were inviting, nor were they always sanitary.

Then in 1889, brothers Samuel and William Childs opened the first Childs restaurant downtown on Cortlandt Street. Within a decade, dozens more Childs outlets opened up, all with “white-tiled walls and floors, white marble table-tops, and waitresses dressed in starched white uniforms, to convey a sense of cleanliness,” explains a 2003 Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) report.

The chain was a runaway success and expanded even further. “Originally intended to provide a basic, clean environment for wholesome food and reasonable prices, the company eventually varied its restaurant designs and menus to reflect the unique location of each outlet,” states the LPC report.

This Coney Island boardwalk Childs opened in a prime location in 1923. The site was close to Steeplechase Park, according to Andrew Dolkart’s Guide to New York City Landmarks. Steeplechase closed in the 1960s, but its most iconic ride, the Parachute Jump, still looms large nearby.

Childs vacated Coney Island in the 1950s. The chain gave rise to countless imitators, and eventually the company was sold and stores across the city shut down. The building on the boardwalk became a candy factory, which operated there until the early 2000s.

Since its designation as a historic landmark in 2003, the site has served as a short-lived roller rink, then was transformed back into a restaurant space. It now sits empty. Still, the nautical-themed facade—so appropriate for the boardwalk of the nation’s most fantastical beach resort—continues to dazzle.

Other former Childs outlets can be found throughout the city. One is now a McDonald’s on Sixth Avenue and 28th Street—at least it was last time I looked.

[Fourth image: NYPL Digital Collection]