Esther Crain's Blog, page 50

May 16, 2022

The solitary walkers across the Depression-era Manhattan Bridge

Social realist artist Reginald Marsh has painted Coney Island burlesque performers, sailors and soldiers, forgotten men at lonely docks and Bowery dives, sideshow gawkers, subway riders, and sexily dressed men and women carousing and enjoying the playground that is 1920s and 1930s Manhattan after dark.

But “Manhattan Bridge,” from 1938, is different. It’s a portrait of a muscular bridge and the ordinary, solitary New Yorkers who walk across it—figures not with Marsh’s usual exaggerated expressions but with their backs turned toward us, unglamorous and getting to where they are going.

The visionary artist with his own museum in a Riverside Drive Art Deco masterpiece

St. Petersburg-born Nicolas Roerich was many things: an archeologist, philosopher, emigre due to the Russian Revolution, and Nobel Prize nominee many times over.

Nicholas Roerich

Nicholas RoerichBut it was his talent as a painter of colorful natural and mystical scenes that brought him to the United States in 1920, when a national tour of 400 of his works launched at the Kingore Gallery in New York City in December of that year.

After the tour and between treks to the Himalayas and India, the charismatic Roerich took up residence in 1920s Manhattan, working out of a 19th century mansion at 310 Riverside Drive, at 103rd Street. With financial help from a Wall Street moneyman and patron named Louis Horch Roerich, he founded the Master Institute of United Arts, a school that offered lectures by top painters like George Bellows.

The Master Apartments, Riverside Drive

The Master Apartments, Riverside DriveThe mansion also housed his own personal museum, where fans could buy copies of his art and writings and debate the merits of his talent. “Talk to his disciples and one encounters almost incoherent adoration,” wrote the Brooklyn Times Union in 1929. “That seems to be the precise word for it. Adoration. Artists are divided in their opinion of his talent.”

Roerich the artist and mystic fascinated Jazz Age New York, and his interest in Eastern philosophies found an eager audience. So when Horch proposed the idea of demolishing the old mansion and building a modern apartment tower on still fashionable Riverside Drive that would devote its lower floors to Roerich’s school, studio, and museum, the two men struck a deal.

The Master Apartments, soon after the building was completed

The Master Apartments, soon after the building was completedThe Master Apartments, also known as the Master Building, (above) made its debut in 1929. It was the tallest building on Riverside Drive, which was transforming from a street of single-family and row house mansions to an avenue of elegant and more restrained apartment houses.

This 29-floor Art Deco masterpiece was designed by Harvey Wiley Corbett, who himself belonged to the Roerich Society. With more than 300 income-generating apartments plus a theater, “the building’s distinctive Art Deco detailing, terraced setbacks, and stupa are easily identified from Riverside Park and the Henry Hudson Parkway,” states the building’s own website. “Its corner windows are reputed to be the first in Manhattan.”

“Guests From Overseas,” 1901

“Guests From Overseas,” 1901According to Anthony Robbins in New York Art Deco: A Guide to Gotham’s Jazz Age Architecture, the Master Apartments “rise to a single, tapered pinnacle, more like a Midtown skyscraper…. [Corbett’s] design relies on geometric patterns, angles, and colors.”

After Wall Street collapsed in 1929, however, fortunes quickly changed for Roerich and his Art Deco tower. “Roerich’s star in America plummeted,” wrote John Strausbaugh in the Observer in 2014. “The Master Building was hit hard by the Depression and went into receivership. Horch renounced Roerich and sued for $200,000 in unpaid loans. The IRS went after Roerich for tax fraud. By 1938 Horch had control of the skyscraper, shoved Roerich’s paintings in the basement and ousted his followers.”

The Roerich Museum was then replaced by the Riverside Museum, which was devoted to contemporary art until the 1970s, when the collection was absorbed by Brandeis University. A new space for Roerich’s artwork was found in 1949 in a brownstone at 319 West 107th Street. Roerich passed away in 1947, but the Nicholas Roerich Museum still exhibits his works today and may be the only museum in New York devoted to one artist.

The Master Apartments went co-op in 1988. The many studio apartments have been combined into larger units, the lobby has been restored, and it remains the tallest building with the most recognizable Art Deco design touches on Riverside Drive.

Cornerstone, with the R and M

Cornerstone, with the R and MTwo remnants of its earlier incarnations remain: a cornerstone bearing the initials R and M (for Roerich Museum, it seems) and the words “Riverside Museum” in small letters above the entrance.

Come see the Master Apartments and other mansions and monuments on Ephemeral New York’s Riverside Drive walking tour June 5 and June 19!

[Third photo: NYPL; fifth photo: Wikipedia; sixth photo: MCNY 2013.3.1.348]

May 9, 2022

This Art Deco skyscraper on 57th Street rightfully celebrates itself

The Fuller Building, on Madison Avenue and 57th Street, has racked up some impressive accomplishments.

Topping out at 40 floors, this 1929 masterpiece was one of New York’ first “mixed use” buildings, with the lower floors boasting high ceilings and a distinct design to attract galleries to 57th Street’s active Jazz Age art scene, according to The City Review.

Art is outside the building as well. Above the entrance is a sculpture of workmen framed around a clock and a relief of the cityscape. Construction themes are reflected on the elevators, and the upper floors feature geometric patterns on the facade.

With so much to boast about, why shouldn’t the Fuller Building have large mosaic medallions of itself embossed in the lobby?

Sure “AD 1929” sounds like the owners expect the tower to be in a museum someday. But this icon has every reason to honor itself and decorate the lobby floor with love letters to its own greatness.

[Second image: structurae.net]

The amazing survival story of the last 3 single-family row houses on Central Park West

If you find yourself facing the corner of Central Park West at 85th Street, you’ll see three stunning row houses, each with different Queen Anne-style touches. They’re charming, confection-like holdouts from the Gilded Age, dwarfed (but not outshined) by their Art Deco apartment tower neighbor.

247-249 Central Park West

247-249 Central Park WestBut before 1930, these three beauties were part of a row of nine spanning the entire block. While their sister buildings met the wrecking ball, they managed to survive—and now are thought to be the last remaining single-family row houses on all of Central Park West.

Their story begins with the Dakota. When this Gothic-inspired apartment building several blocks south was completed in 1884, Gilded Age real estate developers began to imagine Central Park West as a parkside avenue of similarly grand, luxurious apartment buildings.

One builder who apparently didn’t share that vision was a speculative developer of other properties on today’s Upper West Side named William Noble. In 1887, Noble hired architect Edward L. Angell to construct nine single-family row houses between 84th and 85th Streets along what until 1883 had been known as Eighth Avenue.

The “Noble houses,” as numbers 241-249 Central Park West were later called, spanned the entire block, which Noble outfitted with six ornamental lampposts. The fairy tale-like Queen Anne style served as an antidote to the cookie-cutter brownstones lining so many Gilded Age Manhattan streets.

The original nine Noble houses are in the background, 1925

The original nine Noble houses are in the background, 1925“Not only did [Angell] vary his designs for the houses, but he varied the materials too, from red brick to buff-colored brick, from brownstone to carved limestone,” wrote Margot Gayle in 1979 in the New York Daily News.

“The corner houses were the most elegant, each having two exposures, windows with panels of stained glass and a bay-windowed tower terminating in a peaked roof.” Though each row house had different architectural bells and whistles, the gables and chimneys of all the houses reflect the design of the Dakota, the article pointed out.

By 1928, streetcars were long gone from Central Park West

By 1928, streetcars were long gone from Central Park WestCentral Park West as a luxury thoroughfare was in its infancy, and a horsecar line ran up and down the avenue. Still, the Noble houses were pricey. “The houses were at the upper end of the market—they cost $37,000 each in construction alone, exclusive of decoration—and the first occupants were all prosperous,” wrote Christopher Gray in the New York Times in 1990.

Among the first occupants was William Noble; he took number 247 for himself, per a 2014 New York Times article. His neighbor at number 248, a wealthy colonel named Richard Lathers, made news by arranging a reception in his home where relatives of Robert E. Lee and U.S. Grant were invited to bring “North and South together in an informal and quiet way,” according to a biography.

Number 248’s beautiful detailing

Number 248’s beautiful detailingAs the decades went on, the Noble houses changed hands. Meanwhile, Central Park West’s fortunes boomed. Stylish, modern Art Deco apartment buildings that scaled new heights and commanded high prices lined the avenue.

The 1920s marked the beginning of the end for six of the Noble houses. “In 1925, Sam Minskoff, a builder, sued to break the private house restrictions so he could build what was ultimately erected in 1930 as the tall apartment house that replaced 241-246 Central Park West,” wrote Gray.

Number 247 stained glass loveliness

Number 247 stained glass lovelinessWhy didn’t the entire row of Noble houses get demolished? Thank the strong-minded holdout owner of number 249. “Probably all would have been taken down had not the owner of the northernmost of the remaining houses stubbornly refuse to sell,” wrote Gayle. “A neighbor recalls him as a man who knew his own mind, liked to view the park from his windows, wore a bowler, and walked a poodle twice a day.”

This stubborn neighbor was identified in Gray’s article as W. Gedney Beatty, an “architect-scholar.” As a result, “247, 248 and 249 have since survived in the shadow of their taller neighbor,” he wrote.

The 3 remaining Noble houses in 1975

The 3 remaining Noble houses in 1975They were expensive when they were new, and the prices of the remaining Noble houses in today’s real estate market are mind-blowing.

In 2014, number 247—beautifully restored and with its own lap pool—sold for $22 million. Number 248, also renovated to its original beauty, just set an Upper West Side real estate record earlier this year by finding a buyer at $26 million, according to Ilovetheupperwestside.com.

Number 249 Central Park West

Number 249 Central Park West[Third image: New-York Historical Society; fourth image: NYPL; seventh image: MCNY 2013.3.1.34]

May 5, 2022

Upcoming Talks and Walking Tours with Ephemeral New York!

I want to let everyone know about three events happening this month, May 2022, featuring Ephemeral New York. All are open to the public, and it would be great to meet readers of this site!

Photo: Salmagundi Club

Photo: Salmagundi ClubOn Thursday May 19 at 3:30 pm, I’ll be speaking at the Salmagundi Club as part of their Afternoon Tea Talks monthly series. Inside this art and social organization’s beautiful brownstone parlor at 47 Fifth Avenue, host Carl Raymond and I will be talking about Gilded Age New York City, as well as how Ephemeral New York got its start, insider info about the site, and more.

After the talk, tea, sandwiches, and cookies will be available to cap off this casual and fun event. Many of you probably know Carl through his popular podcast, The Gilded Gentleman, plus his historical talks and tours exploring Gotham. Click the link for tickets!

Image: New York Adventure Club

Image: New York Adventure ClubOn Sunday May 15 at 1 p.m. and again on Sunday May 22 at 1 p.m., I’ll be leading a walking tour through the New York Adventure Club, “Exploring the Gilded Age Mansion and Memorials of Riverside Drive.” The tour starts at 83rd Street and ends at 107th Street. In between we’ll walk up Riverside and delve into the history of this beautiful avenue born in the Gilded Age, which became a second “mansion row” and was set to rival Fifth Avenue as the city’s “millionaire colony.” The tour will explore the mansions and monuments that still survive as well as the incredible houses lost to the wrecking ball.

Tickets for May 15 can be bought here, and tickets for May 22 at this link. Hope to see a great turnout on a lovely May day!

[First image: Salmagundi Club; second image: New York Adventure Club]

This 1883 apartment rental on Madison Avenue was one of Manhattan’s first co-ops

I’ve walked past 121 Madison Avenue, at the corner of 30th Street, many times, and it’s always puzzled me.

The red brick, the bay windows, the ornamental detailing along the facade—these architectural hints tell me that the building may have been a stunner when it made its debut, probably in the Gilded Age.

Set on the Gilded Age stylish border of Gramercy and Murray Hill, it was likely surrounded by brownstones and mansion row houses that enhanced its elegance.

Yet there’s something a little forlorn about it, as if it’s been stripped of its true beauty, its colors washed out somewhat. The heavy, block-like extra floors added to the original roof make it seem like the building is carrying the weight of the world.

As it turns out, number 121 does have a grander past. Completed in 1883 when “French flats,” aka apartment residences, were going up in Manhattan but had yet to catch on with the upper classes, the building is one of the city’s very first cooperative apartment houses—with residents owning a stake in the building rather than renting their unit.

The very first co-op building was the Rembrandt, constructed in 1881 at 152 West 57th Street but long demolished. Both the Rembrandt and 121 Madison Avenue were developed by Jared B. Flagg—described by Christopher Gray as a “clergyman-capitalist” in a 1991 New York Times article—and architect Philip Hubert.

The two were behind several other early co-op buildings, like the spectacular failure called the Navarro Flats on Central Park South, as well as the red-brick beauty at 222 West 23rd Street, which became the Chelsea Hotel in 1905. The co-ops were cannily marketed as “Hubert Homes” to help sell the idea of cooperative living as exclusive and homey, wrote Andrew Alpern in his book, Luxury Apartment Houses of Manhattan: An Illustrated History.

The marketing may have been slick, but the apartments inside 121 Madison Avenue sound quite elegant. The building featured “five grandly spacious duplex apartments for each two floors of the building,” stated Alpern. Each duplex apartment’s “entertaining rooms,” as Alpert called them, were on the lower floor, with the bedrooms on the upper level.

“The largest of the apartments had five entertaining rooms opening en suite via sliding mahogany and etched-glass doors: reception room, library, drawing room, parlor, and dining room,” explained Alpern.

This duplex design earned praise by the Real Estate Record and Builder’s Guide in 1883. “The elevator in this 11-story building stops at only five floors and each suite forms a complete two-story house in itself, entirely separate from any other apartment,” according to the Guide.

Early residents included bankers and lawyers, wrote Gray. But you know the story. When elite New Yorkers moved out of the increasingly commercial area around Madison Avenue and 30th Street, number 121 suffered as well. In 1940, the co-op became a rental, and its duplexes were carved into small units, wrote Alpern.

The facade was significantly altered as well, with the cornice and decorative balconies “lobotomized,” as Alpern wrote, and much of the ornamentation as well as the ground floor were gutted.

These days, 121 Madison Avenue is still a rental building, in the recently dubbed NoMad neighborhood. Its “historic, prewar luxury homes” are going for up to 10K per month, according to Streeteasy.

May 4, 2022

What to order from a 1950s Mother’s Day menu from the Gramercy Hotel

Vintage menus from New York City hotels reveal a lot about how food choices and dining habits have changed over the years.

Case in point is this Mother’s Day menu from the luxurious Hotel Gramercy Park for May 8, 1955. The menu is for dinner, with dinner starting at noon. It’s a reminder that what we generally call “dinner” today was typically served a lot earlier in the afternoon; this mention of Sunday in New York during the Gilded Age has it that dinner was always served at 1 p.m. A smaller evening meal would be supper.

The menu itself also has a very feminized look to it, with floral images and pink type. In the 1950s, I doubt anyone complained. Today’s customers might take issue with the traditional female feel.

The menu items, though, are quite hearty, with an assortment of old-school appetizers (stuffed celery hearts, seafood cocktail) and 14 entrees (plus a cold buffet) you would expect from a menu in the 1950s. Lobster Newburgh has an old New York backstory, as it supposedly was first served at Gilded Age favorite Delmonico’s in 1876.

The desserts look divine. I wonder how many moms chose the stewed prunes over the layer cake? As for beverages, this might be the oldest mention I’ve seen on a menu of iced coffee.

[Menu: NYPL]

May 2, 2022

Just how old is the lovely stained glass ceiling at Veniero’s pasticceria?

There’s a lot to love about Veniero’s, the cafe and bakery on East 11th Street since 1894. First and foremost are the pastries, but also the tin ceiling, the old-school glass bakery counters, and the wonderful pink and green neon sign on the facade.

But what I noticed for the first time during a recent visit for gelato was the spectacular stained glass panels spanning the length of the ceiling, with their unusual red, gold, and green floral motifs.

I knew they must have been in the cafe for decades, and I wanted to know just how long and where they came from. On one hand, a 1990 New York Times article about bakeries in Manhattan has it that the stained glass was only installed in 1984.

“The only change over the years [at Veniero’s] has been the addition six years ago of an adjoining warm enclave, with a ceiling of stained-glass panels and the original pressed tin,” the article stated.

However, Veniero’s own website suggests the stained glass dates to the 1930s. During the Depression, owner Michael Veniero left the day-to-day management of the store to his cousin Frank.

“Under Frank’s leadership and eventually ownership, Veniero’s evolved into what it is today,” the site says. Frank “filled his new kitchen with Italian bakers and decorated his new cafe with imported Neapolitan glass that still gracefully adorns our ceiling today.”

This 1850s Lower Manhattan image might be one of the oldest street photos

In the 1850s, New York City’s population reached 590,000. Central Park was mostly an idea, the urban city barely existed beyond 42nd Street, and mass transit meant taking a streetcar pulled by horses.

And at some point in that decade, a dry goods store employee turned daguerreotype studio owner captured this remarkable image of a stretch of Greenwich Street, with more than a dozen men standing with their hands in their pockets beside wood and brick storefronts.

The photographer was Abraham Bogardus. From the 1840s through the 1860s, Bogardus ran his own studio in various locations in Lower Manhattan. Two of those locations were on Greenwich Street: first at 217 Greenwich, and then at 229 Greenwich, according to the International Center for Photography (ICP).

Like the other daguerreotype studio owners congregated around Lower Broadway in those decades, Bogardus mostly did portraits. Considering how popular daguerreotypes were at the time with the public, he likely made a good living.

Yet something must have compelled him to step outside his studio door and capture what he saw, and intentionally or not create one of the oldest surviving street photographs of New York City. It’s not a daguerreotype but an ambrotype, according to Invaluable.com, which posted the image when it was up for auction. (It recently sold.)

Abraham Bogardus in the 1870s

Abraham Bogardus in the 1870sAn ambrotype involves a slightly different process than a daguerreotype but is quicker and cheaper to produce, according to the Library of Congress. “Photographers often applied pigments to the surface of the plate to add color,” the LOC stated of ambrotype producers—which could account for the red brick buildings in an otherwise black and white image.

Besides Baker & Sadler at the far left, the store signs are hard to read. Invaluable.com says one sign advertises a bakery and confectionary, others are for a cobbler, a drugstore, a cabinet making firm, and a jeweler.

Could these men be owners and employees of the stores they stand in front of—or are they practicing the time-honored New York City activity of hanging around on the street wiling away the time?

[Top image: invaluable.com, second image: Wikipedia]

May 1, 2022

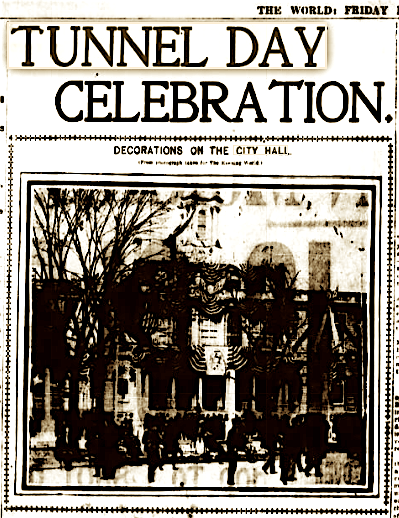

City Hall festooned with flags and finery to celebrate ‘Tunnel Day’

New York used to really celebrate itself. On the opening day of the Brooklyn Bridge in May 1883, fireworks blazed the skies, and a flotilla of ships sailed triumphantly on the East River. When the Statue of Liberty was dedicated in October 1886, the first ticker-tape parade was held amid a day of festivities.

And in 1900, city officials were apparently so excited by the idea of the new subway, they couldn’t wait until the system was up and running to throw a party.

So a celebration open to the public dubbed “tunnel day” was scheduled to mark the start of the digging of the first tunnel and the beginning of underground rapid transit.

Tunnel Day happened on March 24, 1900, and City Hall was decked out with flags, banners, and bunting. Makes sense: City Hall was the focal point for city politicians and other bigwigs, but it was also the site of the groundbreaking of the first station—the “crown jewel” City Hall IRT station.

City Hall Park was also decorated to the hilt. “They are the finest seen in years,” wrote the Evening World the day before Tunnel Day. “The park has become an aerial maze of bright colors. Flags flutter from the treetops and branches.”

Thousands of people watched from the sidewalks of Broadway and Park Row rooftops, 1,000 policemen kept crowds under control, bands played, and officials gave speeches. Mayor Robert A. Van Wyck turned “the first spadeful of earth” with a silver spade, the World noted on March 25. (Crowds tried to grab some of that dirt as souvenirs, alarming the police.)

Tunnel Day was a grand display of pride and progress at a time when the city was on the upswing—in population, land mass, and financial and cultural power. Four years later in October 1904, an even more massive celebration commemorated the opening of the first leg of the New York City subway.

City Hall was covered in flags and bunting once again…but the tradition seems to have died out. I can’t recall a recent event that brought out so many flags and banners.

[Top image: MCNY, X2010.11.584; second image: Evening World; third image: NYPL]