Esther Crain's Blog, page 142

September 12, 2016

The yellow trolley cars of Columbus Circle

In the 1930s, New York was still a city of trolley cars—like the yellow trolleys whizzing (or lumbering?) through Columbus Circle in this 1931 postcard.

By 1956, the last Brooklyn trolley lines bit the dust, victims of the popularity and ease of cars and buses as well as the difficulty of maintaining tracks on city streets.

But this postcard freezes the New York trolley in time, with embedded metal rails crisscrossing one of Manhattan’s few traffic circles.

Looking east, we’re at the doorstep of Central Park, and steps away from the wealth and glamour of then-new hotels like the Pierre and Sherry-Netherland on Fifth Avenue.

Where fashionable Gilded Age ladies lunched

Let’s say you’re a well-off New York woman in the late 19th century, and you’re on an excursion to Ladies Mile—the area roughly between Broadway and Sixth Avenue and 10th and 23rd Streets where the city’s chicest emporiums and boutiques were located.

Shopping is time-consuming, and your stomach starts growling. Where could you grab a bite to eat or a snack?

Social rules at the time made it almost impossible to sit down at a restaurant, as most eateries either banned or discouraged women unaccompanied by men (you might be mistaken for a prostitute).

Social rules at the time made it almost impossible to sit down at a restaurant, as most eateries either banned or discouraged women unaccompanied by men (you might be mistaken for a prostitute).

You certainly couldn’t sit at the counter at a saloon or club, as these were off-limits to women as well.

Your options, then? Going to one of the new women’s lunch rooms or tea rooms, sometimes in the department store itself. Or you could visit a confectionery—a fancy sweets shop that served a light lunch and treats.

Maillard’s Confectionery, on 23rd Street inside the posh Fifth Avenue Hotel, was one of the most fashionable. Billing itself as “an ideal luncheon restaurant for ladies,” the shop was “an Edwardian fantasy” according to The Oxford Companion to Sugar and Sweets.

This description of a new Maillard’s on Fifth Avenue and 35th Street that opened in 1908 (as department stores relocated uptown, so did the restaurants catering to female shoppers) gives an idea of what was on the menu.

“The lunches, as of old, will be light and dainty with the Maillard chocolate and cocoa, coffee or tea. Wines will not be served,” stated Brooklyn Life in October 1908.

Life for New York women after the Civil War was decidedly not coed, with ladies generally expected to stick to and find fulfillment in what was dubbed the domestic sphere.

Life for New York women after the Civil War was decidedly not coed, with ladies generally expected to stick to and find fulfillment in what was dubbed the domestic sphere.

Find out more about how women’s roles began to change in The Gilded Age in New York, 1870-1910.

[Top photo: MCNY: 93.1.1.18170; second image: The Theatre Magazine Advertiser, 1908; third photo: MCNY: 93.1.1.18409; ; fourth photo: MCNY: X2011.34.3811]

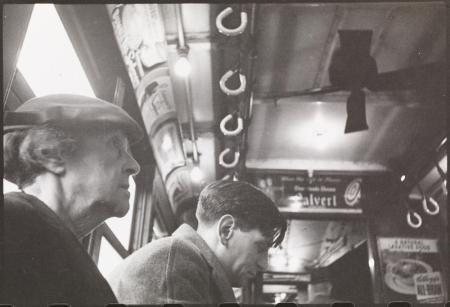

Subway riding in the 1940s with Stanley Kubrick

In March 1947, the popular national biweekly publication Look published a stark, six-page photo feature called “Life and Love on the New York Subway.”

The photographer behind the powerful and poetic images? Future film director Stanley Kubrick—at the time a teenage correspondent for the magazine who sold photo features on everything from city dogs to shoeshine boys to the life of a New York showgirl.

Like street photographers before him (think Walker Evans during the Depression), Kubrick decided to take his camera underground and shoot the people riding the trains.

He hoped to reveal the emotion and humanity behind the typical subway rider’s facade of disinterest and indifference, to capture romance, humor, vulnerability, and loneliness.

He explained how he did it in an a year later.

“Kubrick rode the lines for two weeks,” the article stated. “Most of his traveling to and fro was done at night, as more unusual activities were likely to take place then.”

Kubrick used no flash, and apparently his subjects didn’t know they were caught on film.

“These are truly unusual studies and expressions of life in a subway. Running true to form, drunks, love makers, sleepers, wanderers, and lonesome people were caught, wholly unaware of the fact that they were being photographed.”

His images are striking in their ordinariness, not unlike the faces of subway riders under the streets of New York City today. Train interiors and platforms haven’t changed either.

But taking pictures on a train in the 1940s posed challenges.

“Regardless of what he saw he couldn’t shoot until the car stopped in a station because of the motion and vibration of the moving train. Kubrick finally did get his pictures, and no one but a subway guard seemed to mind.”

The kicker of the Camera story foretells the future. “Stan is also very serious about cinematography, and is about to start filming a sound production written and financed by himself, and several friends.”

These photos and hundreds more from Kubrick can be viewed via Museum of the City of New York digital collections.

[All photos from the MCNY. Accession numbers: photo 1: X2011.4.11107.61A; photo 2: X2011.411107.55C; photo 3: X2011.4.11107.45F; photo 4: X2011.4.10292.63D; photo 5: C2011.4.10292.100C; photo 6: X2011.4.11107.125; photo 7: X2011.4.11107.92E; photo 8: X2011.4.11107.49F]

September 9, 2016

Walking along Madison Square after the rain

I don’t know the name of this painting, but the artist, Paul Cornoyer, often depicted Madison Square and other well-traveled hubs of the Gilded Age city, especially after a rainstorm.

Doesn’t look like Madison Square? It must be the arch and colonnades that are throwing things off. It’s all part of the Dewey Arch, erected at Fifth Avenue and about 25th Street for a parade honoring Admiral George Dewey, victorious in the Philippines in 1898.

The triumphant arch only stood for a year. After the 1899 parade, money was supposed to be raised to make the arch permanent—like Washington Square’s new marble arch. Instead, it was bulldozed in 1900.

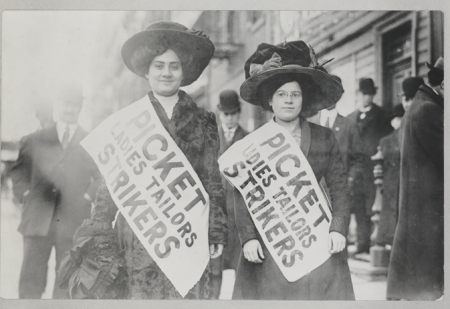

The rich activists of New York’s “mink brigade”

Thanks to the labor movement and the push for women’s suffrage, New York in the first two decades of the 20th century was a hotbed of strikes and rallies—with thousands of women doing the organizing and walking picket lines.

Most of these activists were working-class women, often young immigrants, who toiled for low wages in dangerous sweatshops.

Marching alongside them and helping to finance their efforts were a group of extraordinary wealthy ladies who took their lumps from the press, dubbed in newspaper articles as the “mink brigade.”

These were the wives and daughters of the city’s richest men, women who used their bank accounts to stir up social change rather than entertain at society balls.

These were the wives and daughters of the city’s richest men, women who used their bank accounts to stir up social change rather than entertain at society balls.

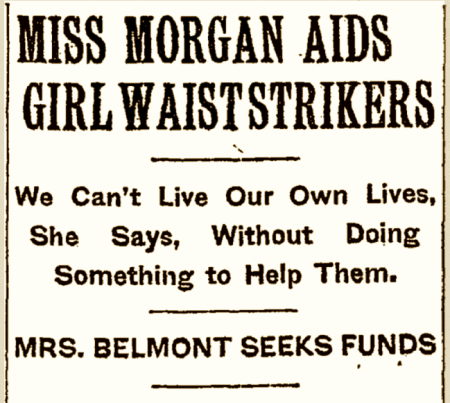

Two well-known members of the so-called mink brigade were Anne Morgan (left), daughter of financier J.P. Morgan, and former society queen bee Alva Belmont, ex-wife of W.K. Vanderbilt and widow of banker Oliver Hazard Perry Belmont.

Through an organization called the Women’s Trade Union League, Morgan and Belmont helped mobilize and support a strike by workers from the Triangle Waist Company (yep, that Triangle company).

That walkout eventually led to a citywide garment workers’ strike in November 1909 known as the “Uprising of the 20,000” (top photo).

“The socialites’ presence generated both money and praise for the strikers,” states Women’s America: Refocusing the Past.

“The move proved politically wise for the suffrage cause as well, because the constant proselytizing of suffrage zealot Alva Belmont, who often bailed strikers out of jail, got young workers talking about the vote.”

By all accounts, Morgan and Belmont (in the photo at right, she’s in the mink) were serious about the causes they espoused and sincere in their efforts.

By all accounts, Morgan and Belmont (in the photo at right, she’s in the mink) were serious about the causes they espoused and sincere in their efforts.

They paid fines for strikers and used their prominence to raise money. Their presence on the actual picket lines kept police brutality at bay.

Called off in 1910, the Uprising of the 20,000 was a partial success, with most sweatshop owners meeting the workers’ demands.

And suffrage, of course, was soon to be a nationwide win. Derided as monied meddlers during their day, the mink brigade turned out to be on the right side of history.

[Third image: New York Times headline December 9, 1909]

The nurse watching over West 12th Street

The scaffolding is gone and the construction vehicles have departed.

The scaffolding is gone and the construction vehicles have departed.

Now, the gleaming new condos (collectively called Greenwich Lane and fetching multimillion dollar prices) carved out of the former St. Vincent’s Medical Center on West 12th Street and Seventh Avenue are ready for occupancy.

Yet amid the landscaped courtyard, new bronze accents, and the cool marble lobby, a few lingering bits of the old Catholic hospital remain.

Take this nurse, carved into the facade above a doorway. Paying homage to the thousands of nurses who tended to St. Vincent’s patients from its opening in 1849 to its demise in 2010, she continues to look out solemnly for passersby on the West 12th Street side.

With St. Vincent’s gone, this faded subway sign in the 14th Street IRT station is even more of a relic.

September 7, 2016

Join Ephemeral New York for upcoming events!

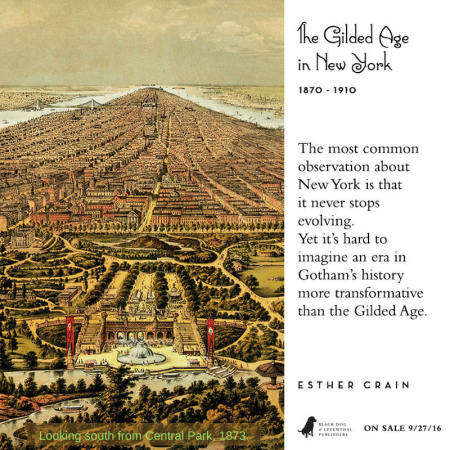

Ephemeral New York would like to announce a few public events focused around the upcoming release, THE GILDED AGE IN NEW YORK, 1870-1910. Hope to see everyone there! More talks and tours are in the works too.

• BOOK LAUNCH TALK: October 5, 2016 at 6:30 PM at the Museum at Eldridge Street

Join me for a reading/Q&A on New York City’s Gilded Age, an era of incredible wealth, poverty, corruption, invention, and rapid social change. Fee: pay as you wish

• AUTHOR @ THE LIBRARY: November 7, 2016 at 6:30 PM at the New York Public Library Mid-Manhattan Branch

This illustrated lecture tells the story of how New York transformed from a small-scale post-Civil War city lit by gas and powered by horses into a mighty metropolis of skyscrapers and subways. Free

September 5, 2016

The magic of Coney Island’s Dreamland at night

Dreamland’s tower, illuminating the summer sky with the help of a million light bulbs, looks like a magnificent cathedral in this 1905 image.

Beach season is almost over, so a postcard reminder of this pleasure paradise will have to suffice until next year. Of course, there’s always September’s Coney Island’s Mardi Gras festival.

[Image: Museum of the City of New York Collections Portal; x2011.34.4375]

A Bank Street building once held prisoners of war

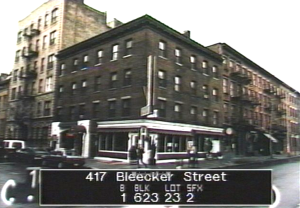

Today it’s a stylish clothing boutique. In the 1990s it housed a Thai restaurant. In the early 20th century, it was a hotel called Laux’s.

Today it’s a stylish clothing boutique. In the 1990s it housed a Thai restaurant. In the early 20th century, it was a hotel called Laux’s.

But whatever business occupies 417 Bleecker Street at the corner of Bank Street, it can’t beat the remarkable role the building played during the early 19th century—when it was called “The Barracks” and held more than 100 British POWs captured during the War of 1812.

You could say that New York lucked out during that military conflict, which lasted until 1815.

The city prepared for combat by putting up fortifications like Castle Clinton at the Battery and blockhouses in what became Central Park. Luckily, the British never attacked.

Yet this war also played out far overseas. “On the afternoon of Feb. 24, 1813, at the height of the War of 1812, the U.S.S. Hornet, an 18-gun warship, set its sights on a British sloop anchored on the Demerara River in Guyana, South America,” wrote Eric Ferrara in The Villager.

Yet this war also played out far overseas. “On the afternoon of Feb. 24, 1813, at the height of the War of 1812, the U.S.S. Hornet, an 18-gun warship, set its sights on a British sloop anchored on the Demerara River in Guyana, South America,” wrote Eric Ferrara in The Villager.

It took minutes for the men on the Hornet to sink the British ship, the H.M.S. Peacock (described not as a sloop but a man-of-war in the Historical Guide to the City of New York, published in 1909).

The Americans then rescued more than one hundred British seamen, recounted a 1918 article in the Daughters of the American Revolution magazine. “On reaching the city, [the British sailors] were taken straight to ‘The Barracks’ at Bleecker Street and confined there till peace was declared,” the article stated.

Interestingly, the Daughters noted that the Americans didn’t treat the British as awful as they treated our POWs during the Revolutionary War, when thousands of men were starved on prison ships in Brooklyn’s Wallabout Bay.

Interestingly, the Daughters noted that the Americans didn’t treat the British as awful as they treated our POWs during the Revolutionary War, when thousands of men were starved on prison ships in Brooklyn’s Wallabout Bay.

After the war was relegated to history and the sailors presumably freed, the passage of time changed the building that no one called The Barracks anymore.

“In 1901 the remains of this structure, which had been used as a private residence with a store at street level, was converted to the Laux Hotel, named after the owner,” states 1969’s Greenwich Village Historic District Designation Report.

“By the late 1930s, the building had been modified still further, faced with brick, and raised from three to four stories.”

Not much of the original Barracks is left in the modernized building. But some remnants of the prison exist here, unmarked and largely unknown.

[Third image: via The Villager; Fourth image: NYC Dept. of Records Photo Gallery, 1980s tax photo]

First day of school in New York: then and now

On September 8, public schools across the city will reopen their doors after summer break.

That’s about a week earlier than opening day in 1915, when kids headed back to “elementary, high, and training schools” on September 13.

A moved-up first day isn’t the only difference between opening day in 2016 and opening day today.

In 1915, about 800,000 kids attended public school in New York City. Department of Education stats from 2015 put that number at just over a million students.

Unlike their contemporary counterparts, teachers in 1915 were not unionized. Most were female, and once they became pregnant, they were fired.

This was actually an improvement over the previous longstanding, perfectly legal practice of booting teachers once they married. That rule was challenged in court in 1904.

One thing hasn’t changed: overcrowding. In 1915, school “congestion” was so bad, thousands of kids were forced to go part-time while some schools, like Morris High School in the Bronx, held two sessions a day to accommodate everyone, according to the New York Times.

Oh, and (most) kids look just as excited on opening day 1915 as they typically do at back to school time—with what look like new clothes, hair ribbons, school bags, and caps for the boys, as these Library of Congress/George Bain images reveal.