Esther Crain's Blog, page 138

November 23, 2016

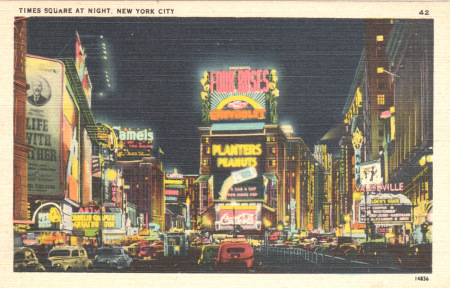

Times Square used to be a festival of neon light

Behold Times Square when it was New York’s premier entertainment district, a festival of neon lights emanating from billboards and theaters.

The postcard carries a 1945 postmark, but it appears to depict Times Square in 1940. Two films released that year, Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator and The Westerner, with Gary Cooper, blaze across movie marquees.

A turkey dinner at the Municipal Lodging House

It’s Thanksgiving Day, 1931, in New York City.

By early 1932, one in three city residents will be out of work. Roughly 1.6 million were on the relief roles, according to the Lower East Side Tenement Museum. Down and out New Yorkers began building a Hooverville in Central Park.

And an astounding 10,000 men waited for their turn to sit down to dinner at the Municipal Lodging House, the public city shelter for homeless men, women, and children at the foot of East 25th Street.

This New York City Department of Records photo captured a group of these men in bulky overcoats and hats. They’re young and old, mostly oblivious to the camera and focused only on consuming their turkey and potatoes.

4 minutes of Macy’s Thanksgiving Parade, 1945

Didn’t get up in time to watch this year’s Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade—in person or on TV?

No problem. Instead, travel back in time to 1945 and take a look at this vintage parade footage, which offers excellent views of mid-century Central Park West, clowns who are not scary, and parade floats inspired by fairy tales rather than blockbuster movies.

1945 was a milestone year for the parade, which started in 1924: it had been suspended for the three previous years because of rubber and helium shortages brought on by World War II, according to AM New York.

November 21, 2016

Firefighters racing to a blaze in 1905 New York

Their engine is pulled by horses, and the long coats these smoke eaters are wearing look awfully bulky. But that’s how New York’s firefighters did it in 1905, when this postcard image was made.

Amazingly, the city’s fire department had only been professionalized since 1865. Prior to that, various volunteer engine and ladder companies put out New York’s fires, sometimes competing with one another to do so.

Amazingly, the city’s fire department had only been professionalized since 1865. Prior to that, various volunteer engine and ladder companies put out New York’s fires, sometimes competing with one another to do so.

Find out more about the rough and tumble early days of the FDNY, when the volunteer companies also served as social and political clubs, in The Gilded Age in New York, 1870-1910.

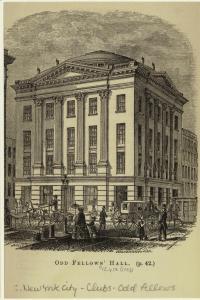

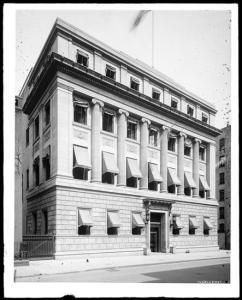

An odd 1848 building known as Odd Fellows’ Hall

Sometimes a building you’ve passed a thousand times in New York suddenly stops you in your tracks.

That’s what happened on a walk to Grand and Centre Streets, when I took a hard look at the curious fortress-like rectangle on the southeast corner.

Its handsome brownstone facade, Queen Anne mansard roof, and many decorated chimneys looked out of place in an area of mostly tenements and low-rise lofts.

Its handsome brownstone facade, Queen Anne mansard roof, and many decorated chimneys looked out of place in an area of mostly tenements and low-rise lofts.

The building came off like a visitor from another New York. And in a way, it was.

It was constructed way back in 1848 as the New York headquarters of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows, a fraternal organization that aided the poor.

[Why the term “odd fellows”? When the group first formed in 17th century Europe before spreading to various cities in America, it was considered odd that people would come together to help the disadvantaged in their community, according to the Odd Fellows website.]

Designed by Trench and Snook, the architects behind retail king A.T. Stewart’s Marble Palace at Broadway and Chambers Street and many of New York’s cast iron edifices, this “Corinthian pilastered palace,” as the AIA Guide to New York City described it, originally had just four stories and a domed roof.

Still, it was celebrated for its beauty and uniqueness. At a dedication of the building in 1849, a large procession marched down Broadway, blocking all omnibus traffic, until it reached Grand Street amid cheering and music, according to The Evening Post on June 5.

Inside was just as lovely, according to Miller’s New York as It Is, from 1866. “It contains a series of highly ornamented lodge-rooms, richly furnished and in different styles of architecture,” the guide noted.

Inside was just as lovely, according to Miller’s New York as It Is, from 1866. “It contains a series of highly ornamented lodge-rooms, richly furnished and in different styles of architecture,” the guide noted.

Odd Fellows’ Hall only served as the organization’s home base in Manhattan until the 1880s.

The group moved uptown, and an extensive renovation—two more stories, the mansard roof—was done to make it more appealing to new commercial and industrial tenants.

Photos from the 1970s show the building to be rundown and vacant. Today, this odd reminder of a pre–Civil War architectural loveliness seems to have been restored.

[Second and third images: Odd Fellows’ Hall in the 19th century; fourth image: the building in 1975, MCNY 2013.3.1.32]

Ghost signs lurking along the Lower East Side

Urban explorers get giddy when they come across ghost signs: faded ads and store signage for businesses that have long since departed their original location.

The Lower East Side is full of these phantoms, thanks to changes in the neighborhood that have displaced longtime retailers and services—like the expansion of Chinatown and the hipsterization of downtown Manhattan.

Turn the corner at Allen and Grand Streets, and you’ll see one ghost sign: a two-story vintage ad on the side of a tenement, with a wonderful arrow pointing toward a nonexistent entrance. What happened to Martin Albert Decorators? They moved to East 19th Street, then to 39th Street.

At the start of the Great Depression, close to 3,550 Chinese Laundries operated in New York City, reported one source. This laundry at 123 Allen Street was one of them.

Nice that the bar which took over this lower-level space kept the weathered old Chinese Laundry sign.

There must be hundreds of massage businesses in the area right now. Lurking beneath this back and foot rub sign is the word “sportswear,” a remnant of the Lower East Side’s past as a center for clothing, fabric, and linen shops.

This ghost sign at 302-306 Grand Street lies hidden under a newer awning. H & G Cohen sold towels and shams, the sign tells us . . . but no digitized trace of the business could be found.

November 13, 2016

The first children’s court was in the East Village

Say you were a 19th century New York kid picked up by cops for pickpocketing or stealing candy.

Say you were a 19th century New York kid picked up by cops for pickpocketing or stealing candy.

Like all alleged offenders, your case would go before a judge, and you might even have been held in one of the city’s infamous prisons, like the Tombs, with other adults.

But in the early 1900s, a novel idea hit in the city: trying minors under age 16 in a special court just for kids, to “guard children against the exposure and environment of crime,” as a 1902 New York Times piece put it.

City law already made a few concessions for minors; for example, they waited for their case in a separate room, so they wouldn’t come into contact with “the intemperate and dissolute classes that are found in police courts.”

But reformers wanted to take it a step further. Most of the crimes kids committed were misdemeanors, and the thinking was that a separate court “inclined toward mercy,” in the words of another Times writer, would help keep children from becoming hardened criminals.

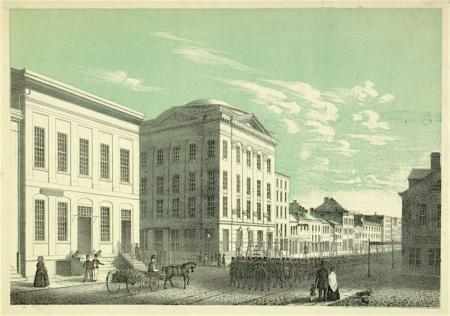

With this in mind, the city’s first Children’s Court opened that year at Third Avenue and 11th Street (second image) in today’s East Village, “with much fanfare,” wrote Robert Pigott in his 2014 book, New York Legal Landmarks.

The building had been part of the criminal justice system in New York already; it was the former headquarters of The Department of Public Charities and Correction.

Thousands of kids were brought in during the court’s early years, and the top charges were disorderly conduct and petit larceny. Forgery, arson, and even drunkeness also made the list of offenses.

Thousands of kids were brought in during the court’s early years, and the top charges were disorderly conduct and petit larceny. Forgery, arson, and even drunkeness also made the list of offenses.

“William Buckley, fourteen years old, was charged with intoxication,” read one Times article in 1905. “He also realized that he had lost his job, by which he had supported himself for two years since the death of his mother.”

“Justice Deuel talked to the lad about the dangers of drinking, released him on parole, and told him to report at once to the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, in the event that a friendly laundryman could not find a place for him.”

Children’s Court didn’t curb the number of crimes committed by kids. But it was deemed a success because judges were able to keep children out of the criminal justice system by giving them suspended sentences or probation, not jail or reformatory time.

Of the thousands of kids brought in, it is “reasonable to state that at least 50 percent would have been committed to institutions under the old method,'” the Times quoted the chief probation officer.

In 1912, Children’s Court moved to East 22nd Street (above left). It’s now part of the city’s Family Court system, but the second building still stands today and is part of Baruch College (above).

[Second photo: MCNY, 1911, 2010.11.41961911; third photo: LOC/Bain Collection, 1902; fourth photo: MCNY, 1917, 2010.7.5154; fifth photo: Google]

A modern facade hides a 19th century building

Paint, glass, brick face—there are lots of ways to cover up the original facade of an old city building and give it a more modern spin.

But sometimes a piece of the old structure ends up peeking through, or it’s impossible to cover it up completely. That appears to be the case with 18 East 14th Street, between Fifth Avenue and University Place.

The second through fifth floors are covered in what looks like 20th century brick face. The sixth floor, though, has the facade of an older turn-of-the-century building, with oval windows similar to its neighbor on the right and 19th century-era decorative touches.

Was this structure really built in 1930, as Streeteasy states? Looks more like it belongs to the bustling 14th Street of streetcars, department stores, piano showrooms, and elevated train stations.

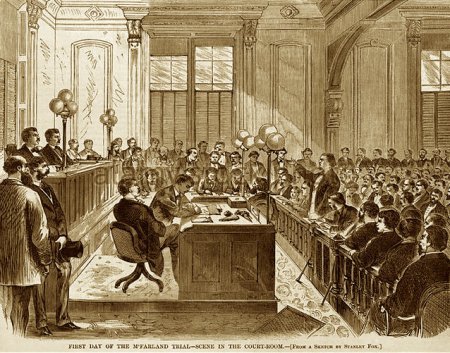

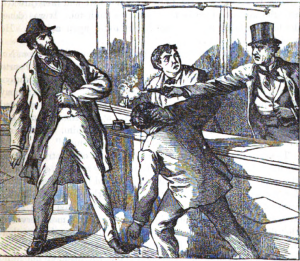

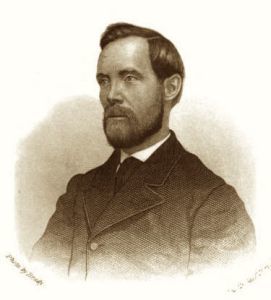

The 1870 murder trial that transfixed New York

Adultery, a jilted husband, an abused wife, a deathbed marriage—the 1870 murder trial of New-York Tribune writer Albert Richardson had it all.

Adultery, a jilted husband, an abused wife, a deathbed marriage—the 1870 murder trial of New-York Tribune writer Albert Richardson had it all.

The story begins in 1857, when Abby Sage, a 19-year-old actress, married Daniel McFarland, who claimed he was a wealthy lawyer.

Turns out he wasn’t a lawyer, nor was he wealthy. Instead, he was an alcoholic prone to violence.

While Sage earned success as a playwright and on stage opposite Edwin Booth at the Winter Garden Theatre, McFarland would drink, going into violent rages and threaten homicide or suicide, then promise he’d clean up his act and find a steady job.

While Sage earned success as a playwright and on stage opposite Edwin Booth at the Winter Garden Theatre, McFarland would drink, going into violent rages and threaten homicide or suicide, then promise he’d clean up his act and find a steady job.

Things changed, however, in 1867, when the couple and their two young sons moved into a boarding house at 86 Amity Street—today’s West Third Street.

There, Sage met another boarder, a widower named Albert Richardson. At the time, he was a writer for the New-York Tribune and had made a name for himself in literary circles. During the Civil War he was a Union spy who escaped a Confederate prison in North Carolina.

Sage and Richardson became friendly and began spending days together, working on their writing. When McFarland found out, he went into an angry spiral, threatening murder and suicide.

Sage and Richardson became friendly and began spending days together, working on their writing. When McFarland found out, he went into an angry spiral, threatening murder and suicide.

Finally, Sage left him—and her friendship with Richardson turned romantic.

McFarland was enraged. Sage began divorce proceedings, and McFarland attempted to get custody of their sons.

Desperate to be free of her violent estranged husband so she could be with the man she loved, Sage temporarily moved to Indiana, where divorce was allowed for extreme cruelty and drunkenness. In fall 1869, 16 months later, she came back East, believing that her marriage was legally over.

Her ex-husband, however, made good on his murderous threat. On November 25, McFarland entered the Tribune office on Spruce and Nassau Streets, pulled out a pistol, and shot Richardson, mortally wounding him.

Richardson was taken to the posh Astor House Hotel, where he lingered for a week. In that time, while McFarland was in the Tombs, he and Sage arranged to be married—by famous Brooklyn preacher Henry Ward Beecher.

Richardson was taken to the posh Astor House Hotel, where he lingered for a week. In that time, while McFarland was in the Tombs, he and Sage arranged to be married—by famous Brooklyn preacher Henry Ward Beecher.

There was never any question that McFarland killed Richardson. But to get McFarland off the hook for his crime, defense lawyers had to shift the focus from the shooting to Sage and Richardson’s relationship, which began while Sage was technically still married.

“The prosecution focused on the misery of the McFarland marriage, with Abby’s relatives and friends, including Horace Greeley, giving testimony,” according to 19th century crime website Murder By Gaslight.

“The defense changed the focus to the adulterous relationship between Abby and Albert Richardson. An intercepted letter from Albert to Abby, coupled with Daniel McFarland’s family history of mental instability, allegedly triggered the insanity in McFarland that led to the shooting.”

“The defense changed the focus to the adulterous relationship between Abby and Albert Richardson. An intercepted letter from Albert to Abby, coupled with Daniel McFarland’s family history of mental instability, allegedly triggered the insanity in McFarland that led to the shooting.”

“The trial lasted five weeks. The jury deliberated for an hour and fifty-five minutes and found Daniel McFarland not guilty.”

[Top image: Murder by Gaslight; second image: Wikipedia; third image: Murder by Gaslight; fourth image: LOC; fifth image: Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 5, 1870; sixth image: Astor House Hotel, 1874, NYPL]

November 6, 2016

5 houses from the East Village’s shipbuilding era

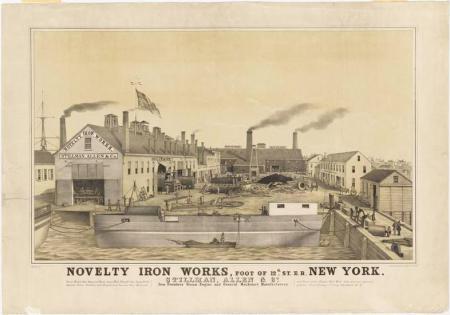

If you traveled back in time to the far East Village of the mid-19th century, you would see a neighborhood sustained mainly by one industry: shipbuilding.

If you traveled back in time to the far East Village of the mid-19th century, you would see a neighborhood sustained mainly by one industry: shipbuilding.

Along the East River, thousands of iron workers, mechanics, and dock men—many who were recent Irish and German immigrants—toiled in shipyards and iron works in what was then called the Dry Dock District, east of Avenue B.

Marshlands were filled in, and row houses, shops, and churches (like the recently restored St. Brigid’s on Avenue B) went up for workers and their families.

“In sight and sound of their hammers along the water-front these master workmen and owners built themselves homes,” wrote the New-York Tribune in 1897.

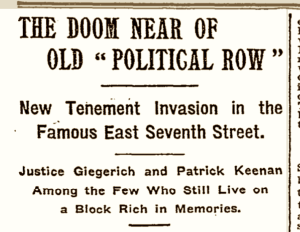

One lovely row was a stretch of Greek Revival–style houses on East Seventh Street (the “Fifth Avenue of the Eleventh Ward,” as the block was called)—between Avenues C and D.

The circa-1840s row was built on “the profits of the sea,” the Tribune stated, describing them as “buildings of fine window casings and door frames and artistic mantels, yet with curious narrow halls and low ceilings . . . both within and without they show themselves to be houses of character.”

Perhaps they were occupied by high-level shipbuilders at first. But as residents of the Dry Dock District gained power and ran for office, the houses acquired a new distinction: “Political Row.”

Political Row “has furnished many office-holders, and there were more office-holders and patriots who are willing to serve the city and county, the State or the country at large, living on that thoroughfare now than on any similar stretch of highway in New York,” stated the Evening World in 1892.

Political Row “has furnished many office-holders, and there were more office-holders and patriots who are willing to serve the city and county, the State or the country at large, living on that thoroughfare now than on any similar stretch of highway in New York,” stated the Evening World in 1892.

“Electioneering goes on there from one end of the year to the other.”

The beginning of Political Row’s end came at the turn of the century, when many of the original houses went down and tenements built in their place.

Newspapers wrote descriptive eulogies, mourning a neighborhood that was “an American District” now colonized by a second wave of immigrants.

Two score years ago,” wrote the New York Times in 1902, the “streets were then lined with trees covered with luxuriant foliage, and each house had its own green patch of yard.”

“Then Avenue D . . . was a thoroughfare that was made brilliant every Sunday by a promenade of all the youth and fashion of the neighborhood.”

Today, five houses on the south side remain. Their facades have been altered; three sport pastel paint. Wonderful details over doorways and windows maintain their character and harken back to a very different East Village of another era.

The row’s future is in danger; the owners of number 264 (right) have applied for a permit to demolish it.

The row’s future is in danger; the owners of number 264 (right) have applied for a permit to demolish it.

The Greenwich Village Society of Historic Preservation is rallying to get the house landmark status, so it can’t be torn down.

Read about the GVSHP’s efforts to save the row and preserve a bit of the East Village’s history.

[Fourth image: New York Times headline, 1902; fifth image, Novelty Iron Works, East 12th Street and the East River, 1840s; MCNY 60.122.7]