Esther Crain's Blog, page 143

September 2, 2016

A Yorkville deli’s wonderful vintage soda sign

New York has thousands of corner delis and bodegas. But how many sport one of these vintage soda-themed store signs?

York Deli on York Avenue and 79th Street is one of the last. Worn and grimy, it’s not the prettiest sign in Yorkville. But it sure has authenticity. (Still, this is 2016, and the deli has a four-star Yelp page.)

Technically these signs with soda or ice cream logos are called “privilege signs,” promotional signs paid for by food corporations for small groceries, lunch places, and delis.

Technically these signs with soda or ice cream logos are called “privilege signs,” promotional signs paid for by food corporations for small groceries, lunch places, and delis.

They used to be on just about every city block. Now, handfuls remain.

You can see more disappearing privilege signs here and read about their history in David Dunlap’s excellent 2014 New York Times piece on these relics of mid-century cities.

[Second photo: Yelp]

An “almost accurate” map of the Village in 1925

By 1925, Bohemian Greenwich Village had been declared dead, killed off by tourists and college kids.

But the neighborhood of curio shops, theaters, tea rooms, and speakeasies still attracted painters, writers, poets, and illustrators.

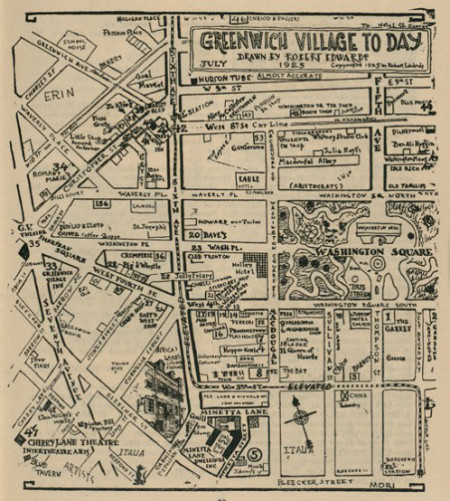

One illustrator was Robert Edwards, who drew this playful and personal map of his Greenwich Village for Quill, a short-lived monthly “little magazine” steeped in satire.

Edwards describes his hand-drawn map as “almost accurate.” It looks pretty on target. Washington Square North is marked “aristocrats,” while south of the park is Italia and west of Christopher Street is Erin, for its Irish population.

Edwards describes his hand-drawn map as “almost accurate.” It looks pretty on target. Washington Square North is marked “aristocrats,” while south of the park is Italia and west of Christopher Street is Erin, for its Irish population.

Romany Marie’s, the (Bruno’s) Garret, and the Crumperie on Washington Place are in history’s dustbin. So is the speakeasy Club Fronton and the Sixth Avenue El, memorialized by John Sloan and e.e. cummings.

The map was part of an exhibit on Greenwich Village staged in 2011 by the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin.

Check out more maptastic views of 1920s and 1930s Greenwich Village.

[Quill cover: Printmag.org]

One of the worst jobs in 19th century New York

In the 1800s, New York was exploding with people. By 1850, the city had a population of a little over 500,000. By 1890, the number was 1.5 million.

That’s a lot of bodies—and a lot of bodily waste. Though flush toilets existed in the late 19th century, they were generally installed in the houses of the rich.

Going to the bathroom for tenement dwellers meant using an outhouse (until the Tenement House Act of 1901 mandated private indoor toilets). Needless to say, waste piled up.

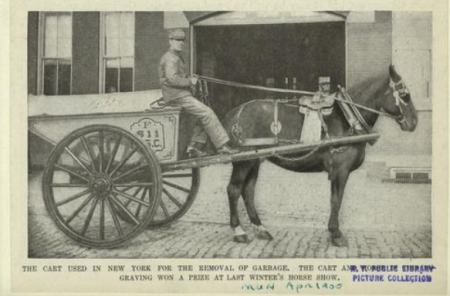

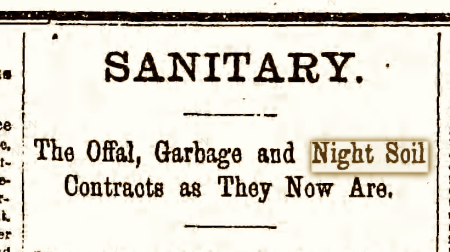

Enter the night soil cartmen. These men made a living after dark, entering tenement districts and removing the “night soil”—a creative euphemism for excrement—from outdoor privies.

The guy who actually picked up the waste (using a cart probably similar to this garbage cart above) apparently worked for a contractor, who bid to take care of unsanitary things like dead animals, trash, and human waste.

Where did they take the night soil? “In New York, the reeking loads were sometimes carted off to country farms to be used as fertilizer,” states a piece from Atlas Obscura.

“But more often they were hauled through the night to a designated pier and dumped into the Hudson or East Rivers (and sometimes mistakenly onto the private boats below), creating a stinking, festering shoreline. The waste would settle into the slips and city workers would periodically have to dredge the excrement so that boats could actually dock.”

The job must have been deeply unpleasant, but it was an important one. Trucking away the night soil certainly helped cut back on disease and made neighborhoods smell less awful too.

Like the blacksmith and streetcar conductor, the night soil cartman disappeared after the turn of the century. Think about his job this Labor Day. Working in a cube farm won’t sound like such a bad thing after all!

[Top photo: NYPL; second photo: NYPL; third image: Brooklyn Daily Eagle; fourth photo: MCNY collections/Robert L. Bracklow, 93.91.281]

August 28, 2016

Fifth Avenue’s most insane Gilded Age mansion

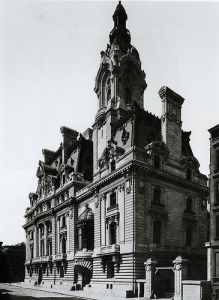

On the avenue dubbed the “Millionaire’s Colony” in the late 19th century thanks to its unbroken line of ornate mansions, one house stood out as the most insanely overdone: William A. Clark’s 7-story Beaux Arts house at 77th Street.

Finished in 1907 after eight years in the making, “Clark’s Folly,” as it was called, broke all records. It cost $7 million to build, featured 121 rooms, and had its own rail line for the delivery of coal.

Amazingly, this monument to money was out of style by the time the final ornament was attached, and it only stood for 20 years.

Amazingly, this monument to money was out of style by the time the final ornament was attached, and it only stood for 20 years.

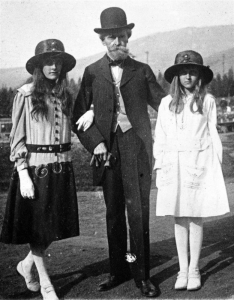

William Clark (below, with his youngest two daughters) was a copper baron who made a fortune in mining and helped found Las Vegas.

He did a stint as senator from Montana in 1899. Forced to resign after a bribery scandal, the deep-pocketed titan who was highly disliked in Washington (even Mark Twain called him out for corruption, describing him as “the most disgusting creature that the republic has produced since Tweed’s time”) got himself elected again in 1901.

Meanwhile, he began building his mansion in New York. This captured the attention of city residents and the press, who estimated Clark’s worth at $150 million.

After Clark left Washington in 1907 with his new wife (a much younger woman who used to be his ward!) and two young daughters, he took up residence in his finally finished marble palace.

The amenities boggled the mind: repurposed pieces from a French chateau, oak panels from Sherwood Forest, Turkish baths, vaulted corridors lined with Gustavino tile, 11 elevators, a pipe organ, 20-plus servant rooms, and galleries for Clark’s extensive art collection.

The amenities boggled the mind: repurposed pieces from a French chateau, oak panels from Sherwood Forest, Turkish baths, vaulted corridors lined with Gustavino tile, 11 elevators, a pipe organ, 20-plus servant rooms, and galleries for Clark’s extensive art collection.

By the time Clark and his family moved in, however, this Gilded Age “pile of granite,” as the New York Times called it, was out of fashion. Architectural critics loathed it.

How Clark felt about this is unclear, and in any case, in 1925, the 86-year-old died inside his citadel (at left, in 1927).

His art collection went to the Corcoran Gallery, and his wife and surviving daughter (her sister succumbed to meningitis in 1919) sold the mansion to an apartment house builder—then decamped for a full-floor apartment at 907 Fifth Avenue down the road.

His art collection went to the Corcoran Gallery, and his wife and surviving daughter (her sister succumbed to meningitis in 1919) sold the mansion to an apartment house builder—then decamped for a full-floor apartment at 907 Fifth Avenue down the road.

There the two remained. Decades after his wife passed on in the 1960s, Clark’s daughter made headlines for an entirely different reason than her father did.

She is Huguette Clark (on the right side of the photo with her father and sister, about 1917), the reclusive heiress who died in 2011 at the age of 104 after many years of living in Beth Israel Hospital.

Clark left a $300 million fortune, and many mysteries.

Gilded Age excess may have gone out of style by 1910. But every financial titan or old money heir staked their claim to the Millionaire’s Colony in the late 19th century, intent on building a marble castle.

Gilded Age excess may have gone out of style by 1910. But every financial titan or old money heir staked their claim to the Millionaire’s Colony in the late 19th century, intent on building a marble castle.

See the amazing photos of this palaces in Ephemeral New York’s upcoming book, The Gilded Age in New York, 1870-1910.

[Top image: Museum of the City of New York (MCNY), X2010.7.2.5452; second image: MCNY, X2010.7.2.21088; third image, via Shorpy; fourth image: MCNY/Phillip G. Bartlett, X2010.11.4911; Fifth image: Wikipedia]

The first confidence man was a New Yorker

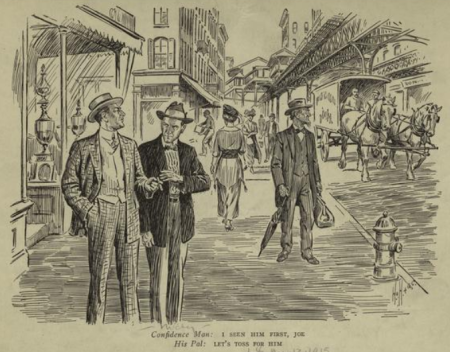

Of course the first confidence man would perfect his scheme in Manhattan. New York was all about making money, a place where greed overtook common sense and hucksters found plenty of victims.

One of those swindlers was a suave, 20-something man with dark hair named Samuel Thompson, who also went by the name of Samuel Willis, among other aliases.

In the booming, increasingly anonymous mid-19th century city, Thompson would approach a stranger who appeared to be well-off, pretend to know the man, and after a little conversation ask, “have you confidence in me to trust me with your watch until to-morrow,” explained the New-York Herald in July 1849.

In the booming, increasingly anonymous mid-19th century city, Thompson would approach a stranger who appeared to be well-off, pretend to know the man, and after a little conversation ask, “have you confidence in me to trust me with your watch until to-morrow,” explained the New-York Herald in July 1849.

“The stranger at this novel request, supposing him to be some old acquaintance not at that moment recollected, allows him to take the watch, thus placing ‘confidence’ in the honesty of the stranger, who walks off laughing and the other supposing it to be a joke allows him so to do.”

After stealing from marks all of the city, Thompson was finally arrested in 1849; he mistakenly hit up a man who he already stole a watch from the year before.

The press made a big deal out of Thompson’s arrest, dubbing him the “original confidence man” and taking a certain glee in the fact that so many New York fat cats fell for the ruse. One writer even proclaimed that the new breed of Capitalist business men were the real con men.

The press made a big deal out of Thompson’s arrest, dubbing him the “original confidence man” and taking a certain glee in the fact that so many New York fat cats fell for the ruse. One writer even proclaimed that the new breed of Capitalist business men were the real con men.

“Let him rot in ‘the Tombs,’ while the ‘Confidence Man on a large scale’ fattens, in his palace, on the blood and sweat of the green ones of the land!” argued a writer from Knickerbocker Magazine.

Thompson was convicted of grand larceny and spent a few years in Sing Sing, then apparently took off to ply his act around the country, though he ripped off another mark in New York in 1855, according to the New-York Tribune.

Naturally, all kinds of scammers began copying Thompson’s brilliant con—leading to the term con artist and continuing a long tradition of New York swindles, from bunco to the selling the Brooklyn Bridge to three-card monte.

Naturally, all kinds of scammers began copying Thompson’s brilliant con—leading to the term con artist and continuing a long tradition of New York swindles, from bunco to the selling the Brooklyn Bridge to three-card monte.

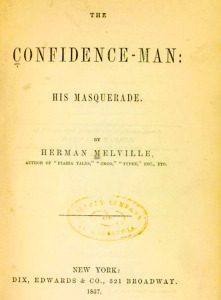

Thompson even inspired Herman Melville, who published The Confidence-Man: His Masquerade in 1857, one of many Melville characters who originated in the headlines.

Hat tip to Jonathan from New York Local Tours for this entertaining bit of New York trivia, via the Crime in NYC tour.

[Top image: NYPL Digital Gallery; second image: New-York Tribune 1855; third image: NYPL]

A Salvation Army Art Deco fortress on 14th Street

In 1880, eight missionaries sent to the U.S. by the British-based Salvation Army disembarked at Castle Garden in Lower Manhattan.

Ridiculed at first, the group’s presence and influence grew, particularly in New York, where “officers” ran rescue homes, soup kitchens, and lodging houses and the evangelical mission turned into what founder William Booth later dubbed “social salvation.”

And of course, they launched the tradition of setting up kettles on busy corners, asking for Christmas dinner donations for needy families.

And of course, they launched the tradition of setting up kettles on busy corners, asking for Christmas dinner donations for needy families.

So when it came time to build national headquarters in the 1920s, Gotham got the nod.

In 1930, a concrete and steel Art Deco complex consisting of offices, an auditorium, and Centennial Memorial Temple opened.

A women’s residence hall was also part of the complex, its entrance on 13th Street.

Though no longer the Salvation Army’s national HQ, the fortress-like structures of 14th Street stand as examples of streamlined Art Deco beauty and perfection.

The complex was designed in part by Ralph Walker, the architect behind New York Art Deco masterpieces such as the Verizon building (now the pricey residential Walker Tower) in Chelsea.

New York is resplendent with Art Deco: movie theaters, offices, apartment residences, and even subway entrances.

[Second photo: Salvation Army Headquarters from 14th Street, Wikipedia]

August 25, 2016

Bathing beauties of the 1896 Sunday Journal

Is this siren showing off at a high-end resort like Long Branch or enjoying the surf at lowbrow pleasure paradise Coney Island?

Both destinations are probably covered in the William Randolph Hearst-owned Sunday Journal. Hmm, could the whole summer resort focus be an excuse to run images of women in bathing costumes?

Look at the writers: Stephen Crane!

[Image: NYPL Digital Gallery]

Before a playground came to Bleecker Street

Our local parks and playgrounds become such neighborhood fixtures, it’s difficult to imagine that they weren’t always part of the cityscape.

That’s why it’s so jarring to see this 1959 photo of the junction of Bank, Bleecker, and Hudson Streets—but no Bleecker Playground, the cheery place of swings and sand always crowded with happy kids and captive parents.

Anchoring that corner in the early 20th century was the formidable Henry I. Stetler brick warehouse. (Beside it is a bandstand-turned-comfort station.) It fits right into the far West Village of the time, an area of warehouses and light industry.

In 1927, a spectacular fire raged through the Stetler warehouse, injuring dozens of firefighters and causing the city to condemn the building. A changing West Village came up with a reason to raze it in the 1950s.

“In 1959, demand for a safe play space for neighborhood children prodded the city to acquire the Stetler Warehouse south of historic Abingdon Square to make way for a playground, the first in the area,” states nycgovparks.org.

“In 1959, demand for a safe play space for neighborhood children prodded the city to acquire the Stetler Warehouse south of historic Abingdon Square to make way for a playground, the first in the area,” states nycgovparks.org.

Seven years later, Bleecker Playground opened (above, in 2010, and at right). It feels like it’s been in the neighborhood far longer.

[Top photo: New York City Parks Photo Archive; second photo: Jonathan Kuhn via New York City Parks Photo Archive; third photo: Wally Gobetz/Flickr]

The cat rescued from a Hell’s Kitchen mailbox

Cat antics and exploits make for irresistible clickbait—come on, who doesn’t love keyboard cat? But felines were huge media stars in the pre-Internet era too.

Case in point: Blackie, a sleek inky furball who ended up inside a mailbox in Hell’s Kitchen just before World War II. Here she is, posing for renowned crime and police photographer Weegee.

The story of her misfortune and rescue is a bit of a tearjerker. “A garage worker called the cops when he heard meows issuing from a box in Hell’s Kitchen, but they couldn’t do anything about it, April 29, 1941,” the original photo caption states, per Getty Images.

“They had to call the Post Office. A mechanic opened the box and found Blackie. Whoever threw her in also tossed in a couple of clams and some pretzels.”

No word on what happened to Blackie after her rescue and turn as a media darling—or who tried to mail her.

[Hat tip: researcher extraordinaire History Author. Photo by Weegee (Arthur Fellig)/International Center of Photography/Getty Images]

August 22, 2016

A curious detective agency sign on Ninth Street

Appearing on the facade of Randall House, an apartment building at 63 East Ninth Street, is this very noir-ish and mysterious sign.

It’s for the William J. Burns Detective Agency. Who was William J. Burns? Known as “America’s Sherlock Holmes,” Burns started out as a Secret Service Agent and then became head of the FBI in the 1920s before founding his own detective agency.

“His exploits made national news, the gossip columns of New York newspapers, and the pages of detective magazines, in which he published ‘true’ crime stories based on his exploits,” states the FBI website.

It’s still a mystery why this sign is on Randall House—an otherwise ordinary residential building in Greenwich Village. As far as I know, it’s the only sign of its kind in New York City.