Esther Crain's Blog, page 145

August 8, 2016

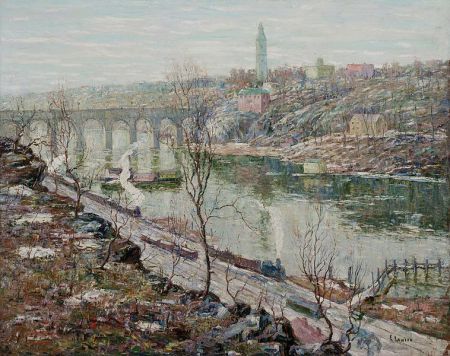

Two enchanting views of New York’s High Bridge

It’s New York’s oldest bridge—a Roman-inspired graceful span completed in 1848 as a crucial link of the Croton Aqueduct, the engineering marvel that brought fresh upstate water to city spigots.

At 140 feet above the breezy Harlem River, it was (and is—it’s now open to the public) a favorite place for strollers as well as artists.

Ernest Lawson was one of those artists. “High Bridge—Early Moon” (above) from 910 “dates from Lawson’s early period . . . when he lived for a time in Washington Heights, at the northern tip of Manhattan,” states the website for the Phillips Collection, which owns the painting.

“Having left the area in 1906 when he moved to Greenwich Village, the artist often returned to paint his favorite sites until about 1916.”

“High Bridge—Early Moon” looks toward the Bronx side of the bridge. In the more somber “High Bridge, Harlem River,” Lawson looks toward Upper Manhattan, the site of the circa-1872 High Bridge Water Tower.

“The motif of the bridge . . . takes on added significance in American art as a symbol of movement and change. As cities grew, bridges were often among the first structures built, their spare designs helping to transform the face of the American landscape from rural to urban.” continues the Phillips Collection caption.

“The motif of the bridge . . . takes on added significance in American art as a symbol of movement and change. As cities grew, bridges were often among the first structures built, their spare designs helping to transform the face of the American landscape from rural to urban.” continues the Phillips Collection caption.

“Lawson’s carefully observed paintings documenting this change conveyed his delight in commonplace views and objects—an old boat, a frail tree, grasses growing along the river’s edge.”

Read more about the High Bridge and how the bridge and the riverfront below it became a favorite recreation area in the late 19th century in The Gilded Age in New York, 1870-1910.

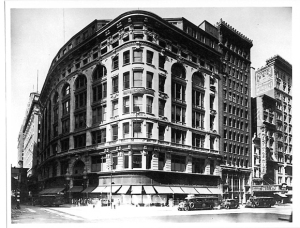

Discount store Korvettes lives on in the subway

Remember the faded and forgotten Gimbels sign inside the 33rd Street PATH station? Turns out another relic of New York’s department store past is hidden away there as well.

Inside a closed-off construction area along a walkway connecting the PATH to the Herald Square subway station is this sign for the underground entrance to Korvettes.

What was Korvettes? New Yorkers who lived in the metro area anytime between the 1950s and the early 1980s know: it was a popular discount retailer with several locations in the city, including one at Sixth Avenue and 34th Street (top photo).

Korvettes went bust in 1980—but this Reagan-era sign was never taken down, even as new retailers moved into its former site, now called the Herald Center.

The Herald Center has quite a retailing history. Before Korvettes moved there in the 1960s and the building was sheathed behind a Brutalist facade, it was a lovely Beaux-Arts building constructed in 1902 for Saks’s Herald Square store (left).

The Herald Center has quite a retailing history. Before Korvettes moved there in the 1960s and the building was sheathed behind a Brutalist facade, it was a lovely Beaux-Arts building constructed in 1902 for Saks’s Herald Square store (left).

(Part of the old Saks facade came back into view last year during construction—a sweet site to behold.)

Korvettes had a strong run—I’d put it above Crazy Eddie but below its Herald Square neighbors like Gimbels and Abraham & Straus in the rankings of defunct city department stores.

This 1970s TV commercial will take you back to the days when Korvettes was big. Thanks to ENY reader B.R. for alerting me to the sign!

[Top photo: John J. Meola/Wikipedia; second photo: Alamy; third photo: Getty Images; fifth image: Staten Island Advance, 1971]

1930s posters pleading for “planned housing”

Disease, fire, crime, infant mortality—could better housing conditions make a dent in these social and environmental problems plaguing Depression-era New York City?

Fiorello LaGuardia thought so. After taking office in 1934, Mayor LaGuardia made what was gently called “slum clearance” a priority and argued that the “submerged middle class” needed better housing.

“Tear down the old, build up the new!” he thundered on his WNYC radio show. “Down with rotten antiquated rat holes. Down with hovels, down with disease, down with firetraps, let in the sun, let in the sky, a new day is dawning, a new life, a new America.”

LaGuardia wasn’t necessarily being melodramatic. Much of the housing stock for poor and working class residents in New York consisted of tenements that were shoddily built to accommodate thousands of newcomers in the second half of the 19th century.

By the 1930s, many tenements were falling apart. And it’s safe to assume that not all of them adhered to the requirements of the Tenement Act of 1901, which mandated adequate ventilation and a bathroom in every apartment.

To help make his case for housing improvement, LaGuardia created the Mayor’s Poster Project, part of the Civil Works Administration (and later under the thumb of the WPA’s Federal Art Project).

Artists designed and produced posters that pushed for better housing—as well as on other health and social issues, from eating right to getting checked for syphilis.

Artists designed and produced posters that pushed for better housing—as well as on other health and social issues, from eating right to getting checked for syphilis.

LaGaurdia achieved his goals. Under his administration, the first city public housing development, simply named the First Houses, began accepting families in today’s East Village in 1935.

The mayor—and his posters—set the stage for the boom in public housing that accelerated after World War II. Whether these developments helped ease the city’s social ills is still a contentious topic.

The Library of Congress has a worth-checking-out collection of hundreds of WPA posters from around the nation.

August 3, 2016

What lunch looked like on Fifth Avenue in 1950

It’s the weekday, probably noon, and thousands of city workers are unleashed on the sidewalks, looking for a quick bite before it’s back to the 1950s nine-to-five office world.

Paris-born photographer Andreas Feininger, who worked for Life through the early 1960s, captures the Midcentury madness and a sea of straw hats in Lunch Rush, shot in 1950.

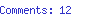

Washington Square Park’s first, forgotten arch

Modeled after Paris’ Arc de Triomphe, the white marble arch that marks the Fifth Avenue entrance of Washington Square has been an icon of Greenwich Village since it was dedicated in 1895.

As recognizable as it is, it’s not the original arch built six years earlier to commemorate the centennial of George Washington’s presidential inauguration.

That first arch (above, in 1890), made of wood and plaster, was meant to be temporary.

That first arch (above, in 1890), made of wood and plaster, was meant to be temporary.

It was also a sneaky way for residents of still-posh Washington Square North to make sure that citywide festivities made it down to their neck of Manhattan.

“To ensure that the Centennial parades would pass near the historic park named for the president, William Rhinelander Stewart of 17 Washington Square North commissioned the architect Stanford White to design a temporary triumphal arch for the occasion,” states the website for the Washington Square Park Conservatory.

Stewart, born and raised in Greenwich Village, was a scion of old New York, a philanthropist from a rich family with major real-estate holdings along Washington Square North (below; number 17 is on the left).

To finance the arch, however, he appealed to friends and neighbors, collecting $2,765 from them.

“Straddling lower Fifth Avenue a half block north of the park, bedecked with flags and topped by an early wooden statue of Washington, White’s papier-mache and white plaster arch was a sensation,” continued Washington Square Park Conservatory.

At the end of the centennial (see the processions in the second photo), White scored a commission to design a permanent arch in marble that would be built at the entrance to the park.

That’s the Beaux Arts beauty recognized for 121 years as a symbol of glory and art.

[Photos: MCNY; “Wet Night in Washington Square,” John Sloan, 1928; Delaware Art Museum]

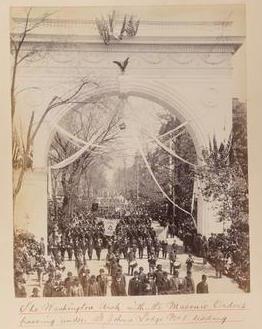

The New Yorker who captured John Wilkes Booth

After news of President Lincoln’s assassination reached the Metropolis on April 15, the city was heavy with grief.

After news of President Lincoln’s assassination reached the Metropolis on April 15, the city was heavy with grief.

Plans were in the works for a two-day viewing and funeral procession that would take Lincoln’s casket from City Hall up Broadway.

Meanwhile, one city resident was scouring the Virginia countryside, leading the detail of soldiers sent to capture on-the-run assassin John Wilkes Booth.

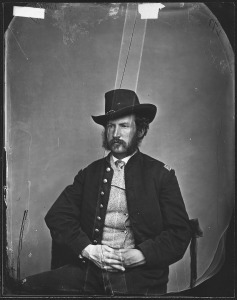

His name was Edward P. Doherty (right). A Canadian immigrant born to Irish parents, Doherty moved to New York in 1860.

When the war between the states began, he joined the 71st New York Volunteers. He spent all four war years in the military, distinguishing himself by escaping capture during the first Battle of Bull Run and earning officer status with the 16th New York Cavalry.

Yet Doherty’s most important assignment came on April 24, after South had surrendered.

Yet Doherty’s most important assignment came on April 24, after South had surrendered.

Summoned to gather 25 military men on horseback, he was then told by a colonel “that he had reliable information that assassin Booth and his accomplice were somewhere between the Potomac and Rappahannock Rivers,” Doherty said later in a report.

He was instructed to take his men south toward Fredericksburg, Virginia, and hunt down Booth and his accomplice, David Herold.

(Herold was part of the unsuccessful plot to kill Secretary of State William Seward, a New Yorker, on the same night Lincoln was shot.)

With the help of locals, Doherty and his soldiers tracked the men to a barn on April 26. There, they tried to negotiate a surrender with a defiant and injured Booth.

Booth wouldn’t let that happen. Ultimately one of the men in Doherty’s detail set the barn on fire, and another shot Booth fatally through the neck. (Herold was brought out alive and later hanged.)

“Chance has connected my name with a great historical event,” Doherty said in 1866.

“Chance has connected my name with a great historical event,” Doherty said in 1866.

After resigning from the Army, Doherty made his way back to New York City in 1886, snagging an appointment as Inspector of Street Pavings and living at 533 West 144th Street (above, the building on the site today).

Doherty died in 1897 and is buried at Arlington National Cemetery; his gravestone makes light of his most famous military assignment.

Lincoln’s assassination was felt profoundly in New York, especially considering the ties Booth had to the city, where he had performed Shakespeare with his actor brothers only months earlier.

The Gilded Age in New York, 1870-1910, delves into it the city’s grief as well as Booth’s connections to New York City.

The Gilded Age in New York, 1870-1910, delves into it the city’s grief as well as Booth’s connections to New York City.

[Top photo: Wikipedia; second image: Trulia; third image: Getty Images; fourth photo: Findagrave.com]

Once again, hat tip to Dean at the History Author Show!

August 1, 2016

The transients of Depression-era New York City

Raphael Soyer, a Russian-born painter who moved to the Bronx in 1912, stuck to the social realist style of painting popular at the turn of the century, as exemplified in his sympathetic 1936 piece, Transients.

“Soyer developed his subjects from New York City’s poorer sections,” states one biography.

“Unlike the painters of the Ashcan School 25 years earlier, Soyer and his contemporaries did not view the city as a picturesque spectacle. Instead, they dwelt on the grim realities of poverty and industrialization.”

The sad fate of these Lafayette Street columns

You could call it one of New York’s first luxury developments: a nine-building stretch of magnificent marble row houses on the recently laid out cobblestone cul-de-sac of Lafayette Place.

The new, two-block street was uptown in the late 1820s, when construction, spearheaded by John Jacob Astor, began. What had recently featured forests and fields was about to become the young city’s most fashionable quarter.

Sing Sing inmates quarried the white marble used to build what would be named LaGrange Terrace (above, in 1895), after the name of the Marquis de Lafayette’s estate in France.

(Lafayette fever was running high in the city; the Revolutionary War hero had just made a rock star-like return visit to the grateful metropolis in 1825).

Completed in 1833 (above) with amenities like running water, central heating, and bathrooms, LaGrange Terrace was occupied by Delanos, Vanderbilts, and Gardiners, as well as short-term residents like Charles Dickens, Edgar Allan Poe, and .

“Society liked the seclusion of the street, and houses were soon built on every side of the terrace,” wrote the New-York Tribune in 1902.

But fashions change, and New York was on a steady march northward. By the end of the 19th century, the marble row caught in the light industry district of renamed Lafayette Street was faded and forlorn.

After they were acquired by department store magnate John Wanamaker (whose store was on 9th Street), five of the buildings had a date with the wrecking ball in 1902. The columns were reportedly salvaged by a builder who intended to use them in another project.

In the ensuing years, LaGrange Terrace has had its ups and downs. A mansard roof was added, and the grimy columns began disintegrating. But earning landmark status gave the row historic recognition.

And what about the marble columns bulldozed a century ago?

They turned up decades later outside a boys’ school in Morristown, New Jersey—on land that was once the estate of the builder who salvaged them.

[Top photo: MCNY; second and third images: NYPL; fifth photo: Wikipedia]

A grisly murder and a city society scion in 1841

Like lots of lurid murder cases, this one involved a rotting body.

Like lots of lurid murder cases, this one involved a rotting body.

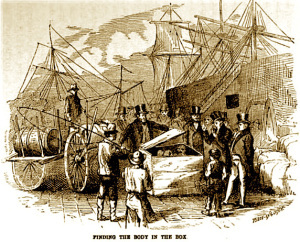

In late September 1841, a sailor on the Kalamazoo—

docked for days at Maiden Lane because rain kept it from heading to its destination, New Orleans—

noticed a rancid odor coming from a shipping crate.

When investigators opened the crate, a man’s decomposing corpse appeared. Officers knew who he was: a Gold Street printer named Samuel Adams, who had been reported missing about a week earlier.

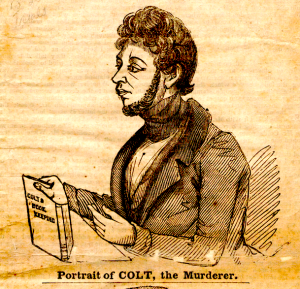

And with the help of the car man who brought the crate to the dock and the clerk who handled the shipping paperwork, officials also knew the killer: a bookkeeper named John C. Colt, who was already being held for the crime.

And with the help of the car man who brought the crate to the dock and the clerk who handled the shipping paperwork, officials also knew the killer: a bookkeeper named John C. Colt, who was already being held for the crime.

Colt wasn’t just any numbers cruncher. He was the brother of Samuel Colt, of Colt revolver fame, and the scion of a prominent New England family.

Colt was socially connected, “of fine personal appearance,” wrote the New York Times, and an instant media magnate in a city already transfixed by the Mary Rodgers “Beautiful Cigar Girl” slaying.

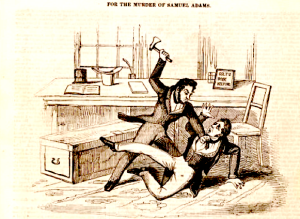

Fittingly for a bookkeeper, Colt committed his crime during a fight about money. In his office at Broadway and Chambers Street on September 17, Adams had come to see Colt about money Colt owed him for printing Colt’s bookkeeping textbook.

Fittingly for a bookkeeper, Colt committed his crime during a fight about money. In his office at Broadway and Chambers Street on September 17, Adams had come to see Colt about money Colt owed him for printing Colt’s bookkeeping textbook.

The argument turned physical. After a struggle, Colt bashed Adams’ skull with a hatchet.

Colt confessed it all: how he scrubbed away bloody evidence, his plan to ship Adams’ body out of the city, and the grisly murder itself.

“I then sat down, for I felt weak and sick. After sitting a few minutes, and seeing so much blood, I think I went and looked at poor Adams, who breathed quite loud for several minutes, then threw his arms out and was silent,” he confessed, according to the website Murder by Gaslight.

“I then sat down, for I felt weak and sick. After sitting a few minutes, and seeing so much blood, I think I went and looked at poor Adams, who breathed quite loud for several minutes, then threw his arms out and was silent,” he confessed, according to the website Murder by Gaslight.

“I recollect at this time taking him by the hand, which seemed lifeless, and a horrid thrill came over me, that I had killed him.”

A famous family with a gruesome death made the trial a sensation.

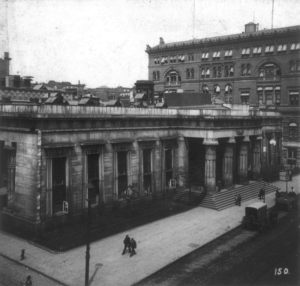

Despite arguing that he killed in self-defense and that temporary insanity led him to try to ship Adams’ body, he was convicted of murder and sentenced to death by (right, in 1896).

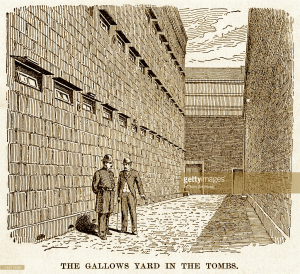

Yet the story doesn’t end with a hanging. On November 18, Colt’s execution date, a fire raced through the Tombs. After the blaze was put out, Colt’s hanging was to go on. But a clergyman found him dead in his cell, a dagger in his heart.

Yet the story doesn’t end with a hanging. On November 18, Colt’s execution date, a fire raced through the Tombs. After the blaze was put out, Colt’s hanging was to go on. But a clergyman found him dead in his cell, a dagger in his heart.

Rumors swirled: was the fire set, and did Colt escape?

What really happened to Colt was such a topic of discussion, it’s even referenced in Bartleby the Scrivener, New York native Herman Melville’s 1853 short story about a Wall Street clerk who “who would prefer not to.”

[Images: New York Sun; NYPL; Getty Images]

July 27, 2016

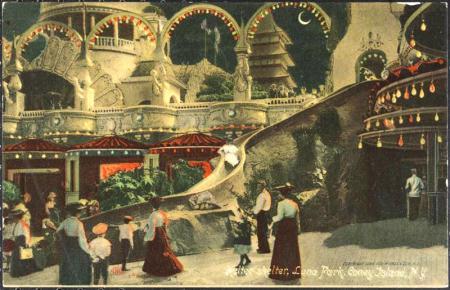

The adults-only slide that thrilled Coney Island

How crazy was Helter-Skelter, a whiplash-fast snaking slide designed for adults that debuted at Coney Island’s Luna Park in 1906?

“Participants rode an escalator to the top of a huge chute made of rattan, then slid down the winding slide before landing on a mattress in front of a crowd of onlookers,” wrote Laura J. Hoffman in Coney Island.

Wish I had a time machine to go back and give it a try!

[Postcard: MCNY, 1907]