Esther Crain's Blog, page 139

November 6, 2016

Rock-throwing and gunfire on Election Day 1864

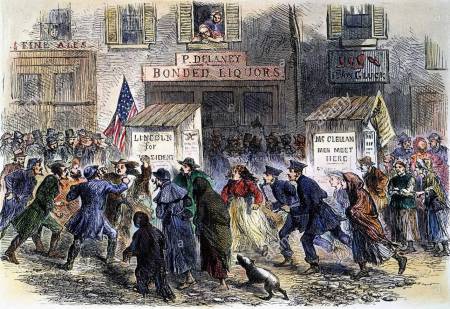

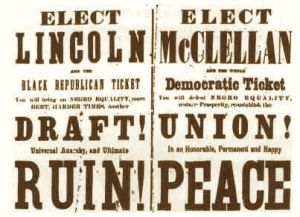

If you think the 2016 presidential election has been brutal, consider the violence triggered by the election of 1864—as seen through the eyes of a bright 9-year-old boy living in a tenement district on Eighth Avenue and 57th Street.

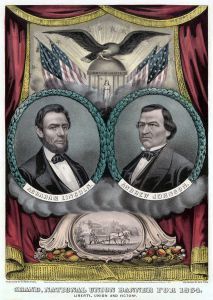

That year, incumbent President Lincoln was up against General George B. McClellan. “The campaign was very bitter on both sides in our neighborhood,” recalled James Edward Kelly, a sculptor who published his memories of the Civil War–era city in Tell Me of Lincoln.

Kelly remembered his pro-Lincoln father, “having rows with the Copperhead neighbors.” Copperheads, of course, were Northerners who were against the Civil War.

Kelly remembered his pro-Lincoln father, “having rows with the Copperhead neighbors.” Copperheads, of course, were Northerners who were against the Civil War.

There were plenty of Copperheads in New York, who felt the war was bad business for New York merchants. Thousands of immigrants, many Irish, who had fought in the war were also disenchanted.

Many Irish women, Kelly wrote, “thought if McClellan were elected on ‘The War is a Failure’ platform, their husbands would come back from the front.”

With a war going on, much was at stake—and it showed in city streets.

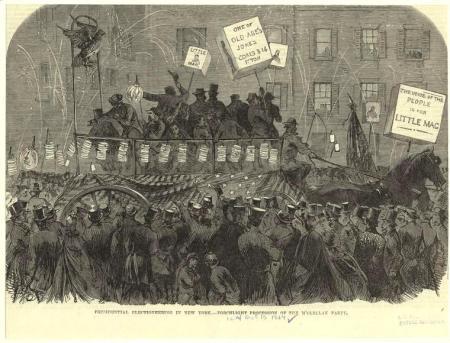

‘The streets were overhung with banners, decorated (or defaced) with so called portraits of Lincoln and Johnson and McClellan and Pendleton,” wrote Kelly. “There were the usual torchlight parades, and the air echoed with glorification of ‘Little Mac,’ and the abuse of ‘Old Abe.'”

“The very curbstones were covered with election posters called ‘gutter snipes.'”

“The very curbstones were covered with election posters called ‘gutter snipes.'”

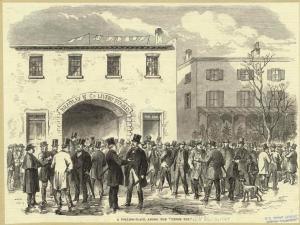

After a brutal campaign season, it was finally Election Day, a holiday in the city. On that cold, rainy morning, Kelly left his house to a polling place.

“I peeped in the doorway. Along the counter were some large glass globes . . . .There was a slit in the top, through which was dropped the folded ballot. . . . The room was filled with tobacco smoke, though I could dimly make out the glint of a policeman’s buttons.”

“Before I could see more, I was hustled aside by a crowd of drunken roughs, who joggled the undisciplined voters swarming in and out at will. I saw a crowd on the corner rush through 57th Street. I followed them to near Sixth Avenue, where they ran into another crowd, and began to pelt one another with stones.”

“Then a shot snapped out. The crowd ceased fighting. . . . The man who had been shot was half lying, resting on his right arm, with his left hand on the wound in his breast, groaning heavily.”

“Hustled aside by the crowd, I trotted homeward, joining the other boys collecting ballots which were scattered thickly upon the sidewalks and along the gutters.”

At day’s end, the action was only beginning, with Election Night bonfires illuminating the sky.

At day’s end, the action was only beginning, with Election Night bonfires illuminating the sky.

“The short November day began to darken. According to the English custom, a voice rang out, ‘Hear ye! Hear ye! The polls are closed!’ The crowd made a charge for the election boxes, carting them off to be used for the fires later that evening.”

“Night came on, cold, bleak, and drizzly. . . . The boys who had been stealing barrels for a month or so, now rolled them out of their cellars, or carried them on their heads in triumph. They built them into mounds before touching them off.”

“With yells of a gang of large boys, the grocer’s wagon was hauled along and run into the flames, but was rescued by the frantic German.”

“With yells of a gang of large boys, the grocer’s wagon was hauled along and run into the flames, but was rescued by the frantic German.”

“Boys danced around and jumped through the flames, till at last, they were hauled off by the ear or the neck by their enraged mothers who had been hunting for them. Finally, the rain scattered the rest, and the embers died down under its dreary beat.”

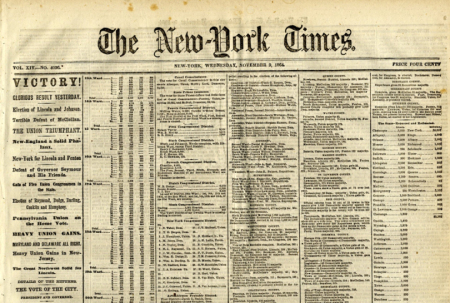

The results weren’t in until the next morning. While Lincoln received only 33 percent of the vote in New York City, voters from the rest of the country gave him a second term.

“Next morning, my father was up bright and early, and called to us, ‘President Lincoln re-elected.’ Then we sat down to a joyous breakfast, while he read aloud the details of the victory.”

Kelly wouldn’t yet know that at the end of November, a group of Confederate sympathizers would attempt to burn down New York. The plot was foiled, and it turned many residents against the South and pro-Union, hoping for victory.

Kelly wouldn’t yet know that at the end of November, a group of Confederate sympathizers would attempt to burn down New York. The plot was foiled, and it turned many residents against the South and pro-Union, hoping for victory.

Interestingly, McClellan’s son, George B. McClellan Jr., became New York’s mayor from 1904-1909.

Read about the Plot to Burn Down New York City in The Gilded Age in New York, 1870-1910.

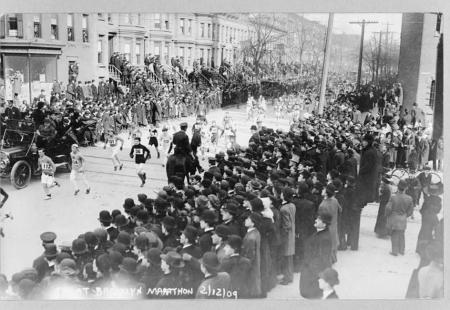

The beginning and end of the Brooklyn Marathon

Runners have been crossing the Central Park finish line of the New York City Marathon, cheered on by thousands of fans, since 1970.

But Brooklyn beat Manhattan on the marathon front by decades. Starting in 1908, Brooklyn began holding its own marathon—on chilly February 12, President Lincoln’s birthday, no less.

For the 1909 race, “the runners started at the Thirteenth Armory in Crown Heights, ran along Ocean Parkway, then past Coney Island’s silent amusements to Sea Gate and back, a 26-mile run,” wrote John Manbeck in Chronicles of Historic Brooklyn.

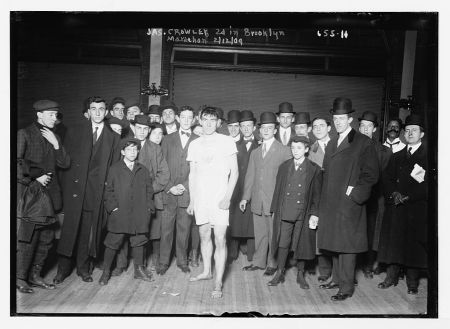

These photos from 1909 show us the 150 runners at the start being sent off by thousands of onlookers . . . and then the first and second-place winners.

The marathon appears to have been held in fits and starts and modified versions through the 1920s, then quietly disappeared.

[Photos: Bain Collection, LOC]

October 30, 2016

Hanging up the wash in a Brooklyn backyard

This bucolic scene of a woman hanging clothes to dry in the sun really is in Brooklyn—the Brooklyn of the 1880s, that is, a boom time that gave the city new neighborhoods, parks, and of course, the Brooklyn Bridge.

Impressionist painter William Merritt Chase lived in Brooklyn from 1887 to 1890, and he often depicted it in his work: Prospect Park, Tompkins Park, and the East River were popular subjects.

“Wash Day—A Backyard Reminiscence of Brooklyn” shows a more intimate side of life in Kings County in a still country-like section of the city. A lone figure hidden behind a bonnet and in the shadows pins sheets to a clothesline, a necessary but mundane task no machine was available to do.

The sauciest society hostess of the Gilded Age

One thing about those self-appointed doyennes of New York’s social scene in the late 19th century: they sure knew how to throw a party.

One thing about those self-appointed doyennes of New York’s social scene in the late 19th century: they sure knew how to throw a party.

But no party host was as outrageous as Mamie Fish, the wife of old money scion Stuyvesant Fish, a banker whose colonial lineage went back centuries in New York.

Born Marion Anthon, Mamie brought an acid tongue and catty wit to society, which was serious business for women like the dour Caroline Astor, who reigned over the social season and who Mamie hoped to usurp.

“Mamie Fish was a hostess with flair and a capacity for the unexpected, qualities notably lacking in Mrs. Astor’s entertainments,” wrote Eric Homberger in Mrs. Astor’s New York.

From her first mansion at 19 Gramercy Park South (right) and later inside her spectacular Stanford White–designed palazzo on Madison Avenue and 78th Street (below), Mamie hosted dinner parties for the city’s elite, complete with after-dinner vaudeville shows in the ballroom.

She “was plain, could barely read and write and had a laugh that was described as ‘horselike,’: writes the blog The Gilded Age Era.

She “was plain, could barely read and write and had a laugh that was described as ‘horselike,’: writes the blog The Gilded Age Era.

“But Mamie was sharp, witty and irreverent which made her an excellent hostess with never a dull moment.

“She once sent out invitations to a dinner honoring a mysterious prince; when the guests arrived they found that the “prince” was a monkey dressed in white tie and tails,” according to one biographical site.

At another party, she reportedly rented an elephant and had dancers feed the animal peanuts as they entertained invitees.

“Make yourself perfectly at home,” she would tell guests, “and believe me, there is no one who wishes you there more heartily than I do.”

“Make yourself perfectly at home,” she would tell guests, “and believe me, there is no one who wishes you there more heartily than I do.”

Perhaps her most fun and frivolous event, symbolizing the excess of the Gilded Age, was the birthday party she threw for her dog—who showed up at the table wearing a $15,000 diamond collar.

Her catty side came out often as well. Speaking about Theodore Roosevelt’s wife Edith, she remarked, “It is said [she] dresses on three hundred dollars a year, and she looks it.”

She also opposed suffrage for women, telling the New York Times, “a good husband is the best right of any woman.”

After Mrs. Astor died in 1908, Mamie inherited the mantle of society queen. But times and tastes had changed, and the social comings and goings of New York’s old money set was never less relevant.

After Mrs. Astor died in 1908, Mamie inherited the mantle of society queen. But times and tastes had changed, and the social comings and goings of New York’s old money set was never less relevant.

Mamie Fish, the “fun-maker” of New York’s Gilded Age, died in 1915.

Amazingly, her homes still survive; former mayor Michael Bloomberg owns the East 78th Street mansion now.

Amazingly, her homes still survive; former mayor Michael Bloomberg owns the East 78th Street mansion now.

For more on the fun and frivolity of late 19th century society, check out The Gilded Age in New York, 1870-1910.

[Top photo: The Esoteric Curiosa; second photo: Wikipedia; third photo: MCNY X2010.28.59; fourth photo: New York Social Diary; fifth photo: The Gilded Age Era]

October 28, 2016

This little witch sends her Halloween greetings

She doesn’t seem very scary, and even the black cat looks like a softie. And wishing jolly good fortune?

This early 20th century postcard doesn’t reflect the ghosts-and-goblins Halloween sensibility we’re used to today. No tricks, no treats, no costume, no spells.

But the church steeples make me think this little witch is flying her broom over Brooklyn’s starry skies (the city of churches, you know), making this an appropriate image for anyone ready to enjoy an urban Halloween.

[NYPL Digital Collection]

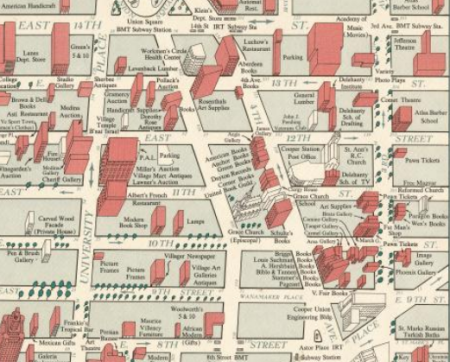

Broadway’s delightful bend at East 10th Street

One of the wonderful things about New York is how much of the city veers off the rectangular street grid codified by the Common Council in 1811.

The sudden bend on Broadway at East 10th Street is one of those street grid exceptions. And as one story goes, it’s the result of a single man intent on preserving his family farm.

Henry Brevoort Sr. was a descendant of the Brevoort family, which settled in New York from Holland in the 17th century.

Henry Brevoort Sr. was a descendant of the Brevoort family, which settled in New York from Holland in the 17th century.

His farm was on the outskirts of the early 19th century city, spanning 86 acres from present-day Ninth Street to 18th Street and bounded by Fifth Avenue and the Bowery.

In 1815, with New York’s population swelling and moving northward, city officials announced plans to expand Broadway to 23rd Street and have it run in a straight line.

Straightening Broadway meant that the busy thoroughfare and the urbanization it would bring would cut right through Brevoort’s estate.

He protested, and the city relented: Broadway would curve to avoid the orchards on Brevoort’s farm, on today’s 10th Street.

Brevoort must have been a persuasive (or stubborn) guy. He apparently disrupted the street grid again by barring “the opening of 11th Street between Broadway and the Bowery in the 1830s and [1840s] to prevent the destruction of the old family farm house,” states brooklynhistory.org.

Yet other sources offer a different explanation for the 10th Street bend, one that has nothing to do with Brevoort.

Yet other sources offer a different explanation for the 10th Street bend, one that has nothing to do with Brevoort.

“Broadway was simply angled to run parallel to the Bowery as these streets reached Union Square,” writes Luther S. Harris in Around Washington Square.

“The city found no pressing need to extend 11th Street east through this relatively narrow strip of land at the expense of a rectory and school for Grace Church.”

Grace Church, of course, has graced the 10th Street bend with its Gothic beauty since 1846. The Brevoort family sold parcels of farmland to church planners so it could be built there, soon a fashionable section of the city.

The actual story may have been lost to history. But in one way or another, we have Henry Brevoort to thank for this scenic bend on Broadway.

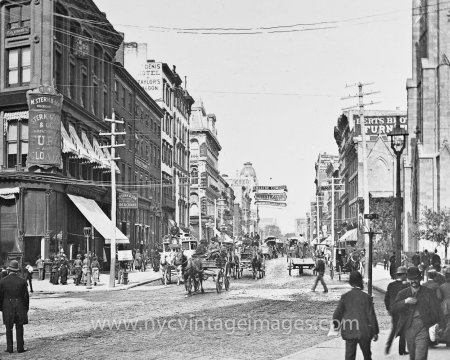

[Top photo: NYPL, 1913; second photo: MCNY, 1908, x2010.11.791; third image: NYPL, 1960; fourth image: MCNY 1920, x2011.34.116; fifth image, 1884, NYC Vintage Images]

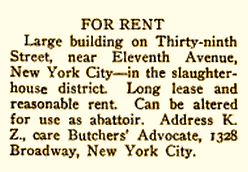

The bloody past of Manhattan’s West 39th Street

West 39th Street close to the Hudson River is an unglamorous road of Port Authority bus ramps, plus traffic from the Javits Center and the ferry station across 12th Avenue.

West 39th Street close to the Hudson River is an unglamorous road of Port Authority bus ramps, plus traffic from the Javits Center and the ferry station across 12th Avenue.

It’s not a pretty three or so blocks. But this concrete stretch is nothing like it was in the 19th and early 20th centuries, when West 39th Street was one of New York’s bloodiest streets.

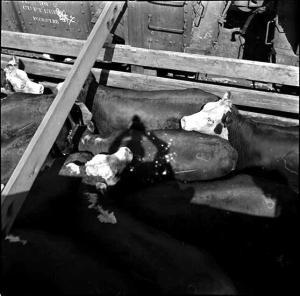

Nicknamed “Abattoir Row,” the street was the center of Manhattan’s slaughterhouse district (previously ), where cattle delivered to the city via ferry or rail line were penned in stockyards before being led into factories, turned into beef, and destined for New York dinner tables.

The earliest abattoirs appeared there in 1850, according to an Evening Post article, which counted 43 separate buildings.

The earliest abattoirs appeared there in 1850, according to an Evening Post article, which counted 43 separate buildings.

“Running through these cellars will be laid a number of pipes, to carry off the blood and filth to a sewer in the rear. . . .”

“A thorough system of ventilation by means of pipes is embraced in the design, and will do much towards preserving the health of those living in the vicinity,” wrote the Post.

Cattle drives were a familiar site on the far West Side even after the turn of the century.

Cattle drives were a familiar site on the far West Side even after the turn of the century.

“Well into the 20th century, cattle drovers would close off 39th, 40th and 41st Streets between 11th and 12th Avenues and herd the cattle from pens to their destinations,” wrote Michael Pollack in his FYI column in the New York Times in 2013.

“Cattle runs across 40th Street continued into the mid-1950s, to a division of Armour & Company a block from the pens. . . . In 1955, an aluminum-sided bridge was built 14 feet above the street so the cattle could walk their last quarter-mile without disrupting traffic.

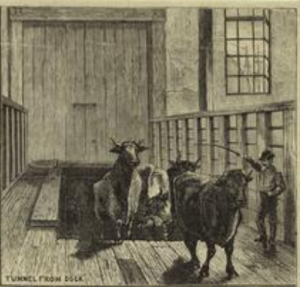

A cow bridge is one thing—a cow tunnel even more fascinating. To dodge traffic, cattle coming into Manhattan via Hudson River barges in the late 19th century were herded through a tunnel under 12th Avenue to the abattoirs on West 39th Street.

Abattoir Row disappeared in the 1960s. The cow bridge has long since been torn down.

Abattoir Row disappeared in the 1960s. The cow bridge has long since been torn down.

And the tunnels? According to Pollack, “if remnants of the tunnels still exist, they may have disappeared beneath the Javits Center.”

This well-researched article does a deep dive into where the cow tunnels might be and how long ago they were in use.

West 39th Street in the old Tenderloin district also had a dicey reputation—of an entirely different kind.

[Second photo: MCNY, 1938 by Sol Libsohn; 43.131.6.162; third and fourth images: NYPL, “The Manhattan Abattoir,” 1877 by V. L. Kingsbury; fifth image: 1922 ad]

October 24, 2016

Loveliness in turn of the century Bryant Park

Here’s Bryant Park in 1913, just a few years after the New York Public Library building opened on the site where the Croton distributing reservoir once stood (hence the park’s original name, Reservoir Square).

But whose bust is that in the foreground?

It’s Washington Irving‘s, according to the Bryant Park Blog. Apparently the city placed this sculpture here because Irving once served on the park’s advisory council.

Removed during a 1930s park renovation, the bust is now part of Washington Irving High School near Gramercy Park.

Is this the city’s oldest intact apartment building?

It’s a five-story, red-brick and brownstone jewel with French Gothic touches at 129 East 17th Street east of Irving Place.

This lovely yet unassuming walkup has a secret: constructed in 1879, it’s considered to be the oldest surviving intact apartment house in Manhattan.

It’s hard to imagine a time when sharing a building with other families was looked down upon in New York.

But until 1870, when Richard Morris Hunt’s Stuyvesant Apartments (right) went up a block away on 18th Street, only the poor shared permanent quarters in tenant houses, aka tenements.

But until 1870, when Richard Morris Hunt’s Stuyvesant Apartments (right) went up a block away on 18th Street, only the poor shared permanent quarters in tenant houses, aka tenements.

New Yorkers of means generally lived in freestanding homes or row houses intended for one family only (and their servants, of course).

With space at a premium in the metropolis, however, well designed apartment houses like the Stuyvesant (the city’s first) were thought to be a solution for New York’s perennial housing shortage.

And apparently many house-hunters agreed. The Stuyvesant, a curiosity as it was being built, was fully rented at a not-cheap $120 per month almost immediately.

The financially devastating Panic of 1873 slowed the introduction of more apartment houses. Once the depression had eased, a handful of new buildings, including 129 East 17th Street, were in the works.

Designed by Napoleon LeBrun, the architect behind so many French Gothic firehouses in New York, number 129 housed five families, with one family to a floor. Each flat consisted of two bedrooms.

Designed by Napoleon LeBrun, the architect behind so many French Gothic firehouses in New York, number 129 housed five families, with one family to a floor. Each flat consisted of two bedrooms.

Early residents of note include the president of the police board, doctors, and an engineer.

Unlike the palatial apartment houses of the 1880s—the Dakota, the Chelsea, and the ill-fated Navarro on Central Park South among others—the gem on 17th Street was all about refined, small-scale living.

But like the Dakota and Chelsea, the facade on number 129 hasn’t been altered, amazingly. Since the Stuyvesant was bulldozed in the 1950s, 129 appears to have earned its title.

“Andrew Alpern contends in his 1975 Apartments for the Affluent: A Historical Survey of Buildings in New York, that No. 129 is the oldest extant ‘genteel’ apartment house in the city,” writes Daytonian in Manhattan.

[Second photo: Berenice Abbott/NYPL, 1935]

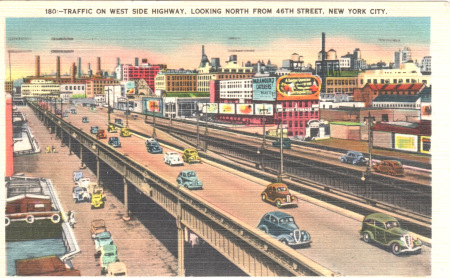

RIP New York’s elevated West Side Highway

If you pine for the days of an edgier New York, then you would have loved the city’s “express highway,” as the back of the 1940s postcard below called it.

This was the elevated West Side Highway, which ran above West Street and 12th Avenue from Lower Manhattan to Riverside Drive.

But most drivers hated it. Built between 1929 and 1951, the freeway officially called the Miller Highway was supposed to make the avenues below safer for pedestrians and less congested.

Unfortunately it was poorly designed, too narrow for trucks and with sharp turns at exit ramps. It was also poorly maintained.

Weakened by years of salt and pigeon poop, a chunk of the highway (left) actually fell into Gansevoort Street in 1973. (Above, at 14th Street, with a piece missing)

Weakened by years of salt and pigeon poop, a chunk of the highway (left) actually fell into Gansevoort Street in 1973. (Above, at 14th Street, with a piece missing)

Today, a few sections of the elevated remain, but most of it was dismantled in the 1980s—to the dismay of some sun worshippers, bicyclists, and urban adventurers, who enjoyed having the crumbling roadway all to themselves in New York’s grittier days.

[Top photo, Wikipedia; third photo: Preservenet]