Esther Crain's Blog, page 144

August 22, 2016

A painter renders Union Square’s sea of humanity

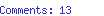

Shop girls, down and out men, lone pedestrians on the way to the elevated train—from the 1930s to the 1980s, Isabel Bishop observed these men and women from her Union Square artist’s studio, painting them in soft tones that reveal their humanity and fragility.

Born in 1902 in Cincinnati, Bishop moved to Manhattan at age 16 to attend the New York School of Applied Design for Women. She then took classes at the Art Students League, developing her talents as a printmaker and painter.

Influenced by early Modernists like Robert Henri and old masters such as Rubens, she became associated with the 14th Street School, a group of realist artists that included Reginald Marsh and Raphael Soyer.

Bishop married in 1934 but kept a studio first at Nine West 14th Street and then at 857 Broadway. The Union Square area in those pre- and postwar decades was home to lower-end department stores, offices, and cheap entertainment venues.

And of course, there was the park itself, a gathering place for everyone from soap-box agitators to workers on their lunch hour to derelict men with no where else to go.

The subject matter right outside her studio suited Bishop perfectly.

“It was in New York’s pulsating environment that Bishop combined her admiration for the old masters with a contemporary taste for urban realism,” states the National Museum of Women in the Arts.

“With her discerning eye, she portrayed ordinary people in an extraordinary manner, often monumentalizing her figures within spaces that barely created context or indicated a location.”

“She chose average models from the streets of Manhattan and often rendered them in a state of physical activity—a sharp departure from the idealized, passive nudes of previous traditions.”

[“Fifteenth Street and Sixth Avenue,” 1930]

Bishop focused many of her paintings on women—the otherwise ordinary women who passed through Union Square, coming in and out of offices or catching a train. Neither mothers nor sex symbols, they “exist for themselves,” as one critic put it.

“On the street corner, in the automat, in the subway and on park benches in fine weather, Miss Bishop proved herself a perceptive observer,” wrote the New York Times in her obituary. “For young women in the big city who were as yet unmarked by life, she had a particular feeling.”

[“Fourteenth Street,” 1932]

As time went on, Bishop’s style seemed to become more muted, with figures of women in what looks like perpetual motion—perhaps a comment on the rise of women in American society.

Bishop kept her Union Square studio until 1984; she died in 1988. This self-portrait was done in 1927, when she was just 25.

Bishop kept her Union Square studio until 1984; she died in 1988. This self-portrait was done in 1927, when she was just 25.

She isn’t as well-known as she should be, but her amber-hued men and women caught in ordinary, fleeting moments speak to the anonymity and motion of urban life in the 20th century.

[Images 1-4; 6: onlinebrowsing.com; Image 5 and 7, dcmooregallery.com]

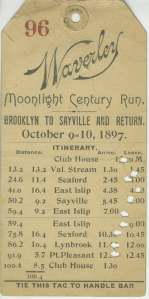

Taking a “century ride” with the city’s wheelmen

In the 1890s, huge numbers of New Yorkers donned new riding suits, bought or rented a bike, and took part in the cycling craze—peddling along park paths or roads newly paved with smooth asphalt.

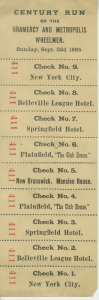

Leisurely rides were fine for the masses. But for hardcore wheelmen (and sometimes wheelwomen) looking for a real challenge, nothing beat the exhilaration of a new kind of competition: the century ride.

A century ride clocked in at 100 miles. It wasn’t a race but a feat of personal endurance. Each rider had 14 hours to get from start to finish and prove their cycling prowess.

A century ride clocked in at 100 miles. It wasn’t a race but a feat of personal endurance. Each rider had 14 hours to get from start to finish and prove their cycling prowess.

“Bicycling clubs were formed all over the city,” reminisced future governor Al Smith in his 1929 autobiography, Up to Now.

“You acquired full membership when you belonged to what was called the Century Club. That meant you had ridden 100 miles in a single day.”

“You acquired full membership when you belonged to what was called the Century Club. That meant you had ridden 100 miles in a single day.”

Every neighborhood had a club, among them the Kings County Wheelmen (known as “scorchers” for their speed), the Riverside Wheelmen (bottom photo, 1888), and the Williamsburgh Wheelmen (top photo, in 1896).

Century rides were popular with young, athletic men. “With a number of young men from my neighborhood, I left Oliver and Madison Streets at nine o’clock on Sunday morning and wheeled to Far Rockaway,” wrote Smith.

“We went in swimming, had our dinner, and wheeled back.”

“We went in swimming, had our dinner, and wheeled back.”

Century rides often went round trip from Brooklyn to Eastern Long Island, as the ticket at the top right shows.

Another ticket from of an 1895 century ride lists each stop on the route from New York City to New Brunswick and back.

Century rides still take place today, and they sound like a lot of (very exerting) fun.

But their heyday remains the turn of the 20th century, when safer, more accessible bikes hit the market just as leisure time began to rise and a trend toward physical fitness gained popularity.

And street pavements improved—thanks to the invention of asphalt, which was put down on an increasing number of city roads that were once paved with blocks, stones, even wood.

And street pavements improved—thanks to the invention of asphalt, which was put down on an increasing number of city roads that were once paved with blocks, stones, even wood.

The cycling craze wasn’t the only sports trend to hit New York in the 1890s. Baseball, tennis, boxing—find out more in Ephemeral New York’s upcoming book, The Gilded Age in New York, 1870-1910.

[Top photo: MCNY; second and fourth images: MCNY; third photo: W.H. Anderson, New York State Century Club winner; fifth photo: MCNY]

August 18, 2016

A solitary statue before the Williamsburg Bridge

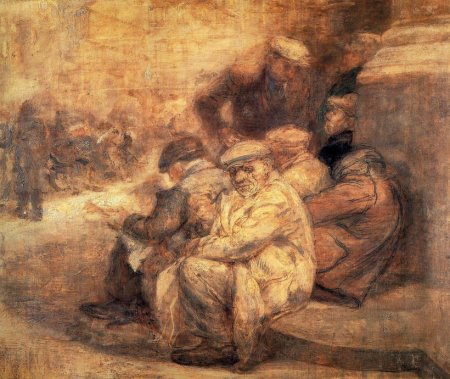

Welcome to Williamsburg Plaza, on the Brooklyn side of the 7-year-old Williamsburg Bridge, in 1910. No bus turn-arounds, no skateboarders or cyclists, and no graffiti.

And no people either. Now called Continental Army Plaza after the equestrian statue of George Washington at Valley Forge in the center, it’s still an often empty plaza and transit hub.

Washington and his horse rise high above it all before the entrance to the bridge.

[Postcard: MCNY]

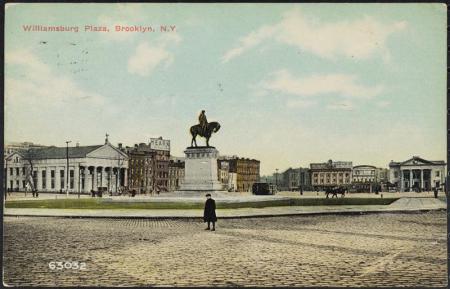

A massive menu at the Manhattan Beach Hotel

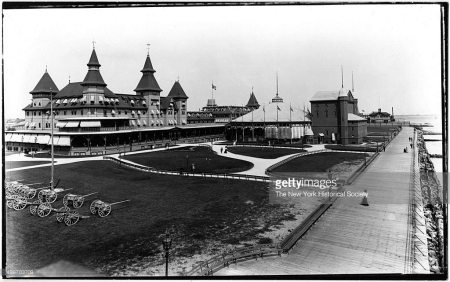

Despite the hopes of its Gilded Age developer, the spectacular oceanside resort of Manhattan Beach, Brooklyn never developed the cache of old money Newport or elegant Long Branch.

But the upper-class guests who made the Queen Anne–style Manhattan Beach Hotel a premier sand and surf destination after it opened in 1877 certainly dined well.

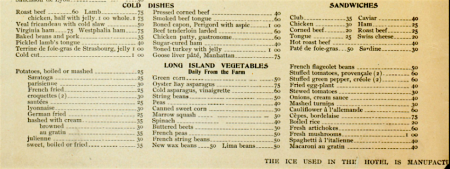

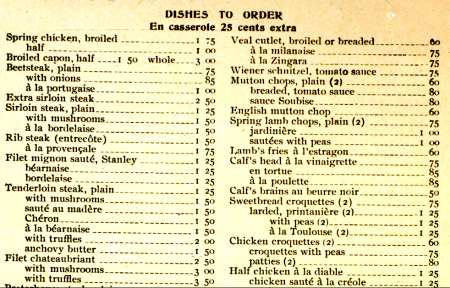

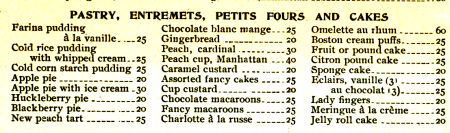

This menu from the 1905 summer season reveals hundreds of dishes, from shellfish to soups to salads to “Long Island vegetables,” perhaps a nod to Kings County’s vegetable-producing past.

Calf’s head, calf brains, sweetbreads—the hotel guests liked their organ meats. Dessert doesn’t disappoint either. Look, they offer charlotte russe, a much-missed lost food of New York City.

By the time this menu (view it in its four-page entirety) was printed, Manhattan Beach’s glory days were behind it.

The enormous resort was demolished in 1912, not long before its rivals, the Brighton Beach Hotel and the Oriental Hotel, also met the wrecking ball.

[Menu: NYPL; photo: Getty Images]

August 14, 2016

A peek inside Grand Central Terminal in 1939

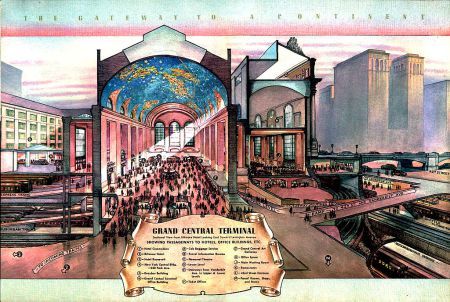

From the New York Central Railroad comes this cool cutaway poster into Grand Central Terminal circa 1939, when train travel reigned supreme.

The zodiac ceiling in the main concourse looks beautifully blue. There’s the main waiting room, now called Vanderbilt Hall, as well as a restaurant concourse, plus various lower levels connecting passengers to commuter trains and subways.

What happened to the art gallery on the third floor above the main waiting room?

A robber baron gunned down in a Broadway hotel

If ever a New Yorker could be described as an unscrupulous, gaudy vulgarian, it would be “Jubilee” James Fisk.

If ever a New Yorker could be described as an unscrupulous, gaudy vulgarian, it would be “Jubilee” James Fisk.

“He was a striking figure, tall, florid, very fat,” wrote Lloyd Morris in Incredible New York. “His light brown hair was pomaded and carefully waved, his mustache waxed to fine points, and huge diamonds blazed on his frilled shirt front and pudgy fingers.”

Fisk was a financier, unprincipled and notorious even in a Gilded Age city that celebrated greed and showiness.

In 1868 he and his business partner, Jay Gould, were responsible for the Black Friday stock market crash, the result of their plan to manipulate the price of gold.

In 1868 he and his business partner, Jay Gould, were responsible for the Black Friday stock market crash, the result of their plan to manipulate the price of gold.

They made millions off the scheme, though, just as they profited handsomely after they joined forces with Boss Tweed to gain control over and loot the Erie Railroad.

“He never pretended to be governed by anything but expediency and self-interest,” wrote Morris. “And he conducted his life in full view of the public.”

That may have been Fisk’s fatal mistake. Because when another business partner decided to kill him, he knew exactly where to find him.

That may have been Fisk’s fatal mistake. Because when another business partner decided to kill him, he knew exactly where to find him.

That would be Edward Stokes. who entered the picture in 1869. The flashy son from a well-off New York family, Stokes convinced Fisk to invest in a deal to reopen an oil refinery in Brooklyn.

Stokes got money from Fisk—and he also ended up with Fisk’s mistress, Josie Mansfield (below), a would-be actress who had “an exquisite figure and perfect features, large black-lashed eyes, magnificent glossy black hair,” wrote Morris.

Mansfield and Stokes were now the talk of the town; everyone, including Fisk, eventually knew about their affair.

Meanwhile, by 1871, Fisk’s and Stokes’ refinery deal went sour. Unless he paid him an additional $200,000, Stokes threatened to release a series of love letters between Fisk and Mansfield that presumably reveal Fisk’s shady business practices.

Meanwhile, by 1871, Fisk’s and Stokes’ refinery deal went sour. Unless he paid him an additional $200,000, Stokes threatened to release a series of love letters between Fisk and Mansfield that presumably reveal Fisk’s shady business practices.

After some legal maneuverings, Fisk had Stokes and Mansfield indicted for extortion.

When Stokes found out about the extortion charges on January 6, 1872, he packed his pistol, went to the Grand Central Hotel—a new hotel on Broadway and West Third Street popular with Fisk’s posh and powerful crowd—and waited for Fisk, who was due to meet friends there.

“He knew that Fisk always entered by the ladies entrance, so Stokes went in first and waited on the second floor landing,” states Murder by Gaslight.

“When he heard Fisk climbing the stairs Stokes started down saying: ‘now I’ve got you.’”

“When he heard Fisk climbing the stairs Stokes started down saying: ‘now I’ve got you.’”

Stokes fire point blank. Fisk cried out in pain, and Stokes shot again. Fisk collapsed on the staircase leading to the lobby but gave a dying declaration that Stokes was his killer.

His life ended the next morning at age 36. Stokes served four years in prison.

Fisk was the consummate Gilded Age robber baron, yet he had his admirers, many of whom paid their respects in the foyer of the Grand Opera House on Eighth Avenue and 23rd Street, where Fisk had his offices and his body lay in state.

Brooklyn preacher Henry Ward Beecher had disparaged Fisk as “the glaring meteor, abominable in his lusts and flagrant in his violation of public decency.”

Brooklyn preacher Henry Ward Beecher had disparaged Fisk as “the glaring meteor, abominable in his lusts and flagrant in his violation of public decency.”

But younger New Yorkers who came of age as the Gilded Age began seemed to admire his “smartness and shrewdness,” explained Morris.

“In refusing to be bound by the traditional moral code, in declining to become the prisoner of convention and decorum, in rejecting the easy compromise of hypocrisy, Jim Fisk had shown an intrepidity that compelled their admiration,” he wrote.

Power, greed, lust, corruption—the Gilded Age was one of notorious crimes and murder trials, as The Gilded Age in New York, 1870-1910, available now for pre-order, lays out.

[Top photo: Wikipedia; second photo, MCNY, 1910; third photo: NYPL; fourth photo: via Minneapolis Star Tribune; fifth and sixth images: covers of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, January 1872, NYPL]

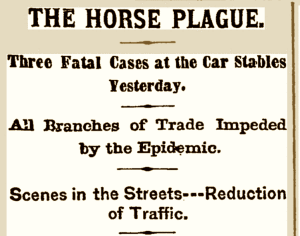

The 1872 “horse plague” cripples New York City

It started in Toronto in the summer of 1872, then spread to New England and Michigan before finding its way to New York in the fall.

It started in Toronto in the summer of 1872, then spread to New England and Michigan before finding its way to New York in the fall.

“The Horse Plague,” read the headline of the New York Times on October 25. “Fifteen thousand horses in this city unfit for use.”

New York had seen outbreaks of disease among horses before, most recently in 1871. But this epizootic of equine influenza was different, sickening (but rarely killing) nearly all horses exposed to it.

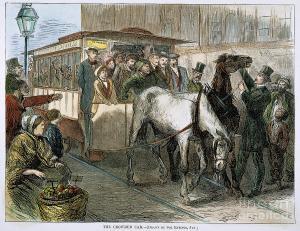

This was a big problem in New York at the time. In a city powered by horses—pulling stages and street cars filled with people, hauling heavy wagons and drays of raw materials and merchandise—business and travel were all but shut down.

Stage lines on almost all avenues were suspended or put on greatly reduced schedules. The express companies that handled business deliveries within the city were closed or scaled back.

Stage lines on almost all avenues were suspended or put on greatly reduced schedules. The express companies that handled business deliveries within the city were closed or scaled back.

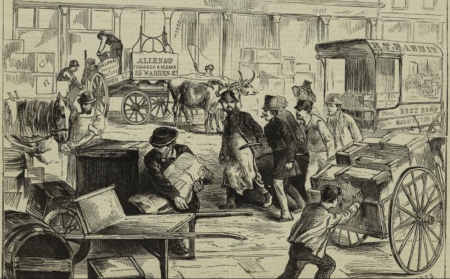

In a city without horsepower, men were forced to do the labor horses usually did (above sketch).

“People were forced to transform into beasts of burden, using pushcarts and wheelbarrows to transport the merchandise that was piling up at docks,” wrote Nancy Furstinger in Mercy.

Oxen (above) were even brought in to take over some of the work, their handlers charging $10-$12 a day for their use.

Oxen (above) were even brought in to take over some of the work, their handlers charging $10-$12 a day for their use.

Not every horse owner showed mercy. The New York Herald on October 26 reported that one street car line “is running the horses as long as they will stand up, and the result promises to be fearful in the extreme, as many of them have dropped down in the street from overwork.”

Henry Bergh (left and checking street car horses in the illustration at top), who headed the recently formed American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, stood outside of Cooper Union and personally “ordered the brutes to stop driving the gasping beasts.”

The conditions horses lived in were partially blamed for the outbreak. “The car and stage horses of this city suffer invariably from all possible forms of equine disease . . . badly fed, worse housed, overworked, and never groomed, they are ready victims of disease,” commented the Times.

The conditions horses lived in were partially blamed for the outbreak. “The car and stage horses of this city suffer invariably from all possible forms of equine disease . . . badly fed, worse housed, overworked, and never groomed, they are ready victims of disease,” commented the Times.

The outbreak was over in New York by December, and horses went back to work, doing their duty as the “mute servants of mankind,” as Bergh called them, until they were replaced by automobiles.

[Top image: Harper’s Weekly; second image: NYPL; third image: NYT story October 27, 1872; fifth image: MCNY]

August 11, 2016

Taking a spin on Coney Island’s “Witching Waves”

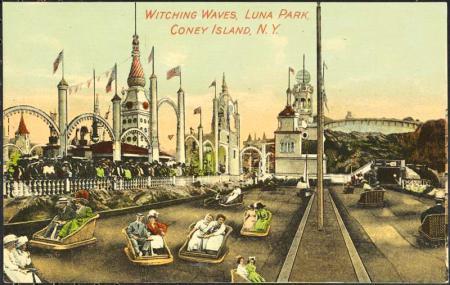

The variety and creativity of amusements at turn-of-the-century Coney Island was astounding. This 1910 postcard shows one of the most popular rides, the Witching Waves.

Invented by the same man who patented the revolving door and installed at Luna Park, “it consisted of a large oval course with a flexible metal floor whose hidden reciprocating levers could induce a moving wave-like motion,” explains Coney Island site westland.net.

“While the actual floor didn’t move, the continuously moving wave propelled two seated small scooter-like cars forward while patrons steered.”

[Postcard: MCNY]

The 1852 stable-turned-synagogue in the Village

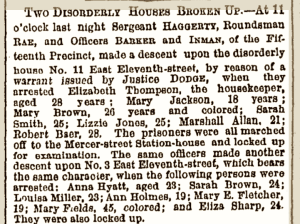

In a neighborhood filled with architectural anomalies, the little house with the front yard at 11 East 11th Street has a curious 164-year history. In that time, it went from stable to brothel to garage to private home and finally becoming a synagogue half a century ago.

First things first. The house was built in 1852 as a carriage house for George Wood, a wealthy lawyer who that same year constructed a stately mansion next door at 45 Fifth Avenue.

In that antebellum era, lower Fifth Avenue was a cream-of-the-crop street lined with freestanding mansions.

In that antebellum era, lower Fifth Avenue was a cream-of-the-crop street lined with freestanding mansions.

The families who occupied these impressive homes needed places to keep their horses, so they put up stables nearby set back from the road with a front yard for hitching.

The 19th century went on, and the richest residents moved northward. By the 1860s, Wood’s former carriage house had become a “disorderly house” raided a few times by the police, reported New York Times.

At the century’s end, development hit. Most of the grand mansions were remodeled or replaced by apartment residences; the carriage houses were demolished.

At the century’s end, development hit. Most of the grand mansions were remodeled or replaced by apartment residences; the carriage houses were demolished.

Yet the stable with the tidy front yard survived. With the arrival of the automobile era, it was turned into a garage with a loft, reported the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation.

11 East 11th Street “now has window arrangements typical of the 1920s,” the GVSHP wrote.”It has been roughcast in stucco with diamond-shaped tile patterns set in the parapet, which is crowned by a stone coping stepped up at the ends above small, square blocks.”

11 East 11th Street “now has window arrangements typical of the 1920s,” the GVSHP wrote.”It has been roughcast in stucco with diamond-shaped tile patterns set in the parapet, which is crowned by a stone coping stepped up at the ends above small, square blocks.”

In the next decades, the little house served as a private residence and a “light protector” for the bigger Van Rensselaer Hotel next door.

In 1959, the Conservative Congregation of Fifth Avenue—

which had been holding services in a hotel—made the former stable with the ginko tree in the front yard its synagogue.

This year, looks like the house and property have been approved for a renovatation.

[Newspaper article: NYT July 21, 1867; fourth photo: 1951, NYPL]

Manhattan street names on tenement corners

If there’s an actual name for these cross streets carved or affixed to the corners of some city buildings, I don’t know what it is.

But they’re fun to spot anyway. I’ve never seen one quite like this decorative sign on an otherwise unremarkable tenement at 169th Street and Broadway.

Fancy, right? This one at Horatio and Washington Streets is also a notch above the usual corner address sign, which is typically carved into the facade in a plain font.

A good example of the traditional style is this one below, worn and so faded it’s hard to see the letters, at Mott and Bleecker Streets.

I’ve heard that these street signs are up high because they were meant to be seen from elevated trains. But there were no trains running on Mott and Bleecker, or Horatio and Washington.

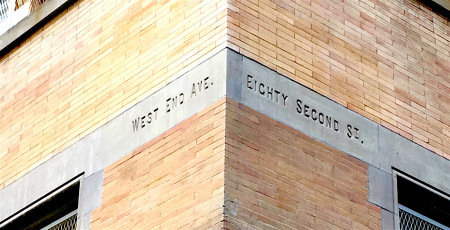

Or West End Avenue and 82nd Street, for that matter. This is a beauty of a sign that’s survived the elements on the circa-1895 facade of former Public School 9, now strangely called the Mickey Mantle School.

Some of my favorites are carved into tenements in the East Village. And of course, the loveliest in the city is at Hudson and Beach Streets.