Jonathan Clements's Blog, page 310

October 14, 2020

Go Long

WHEN I WAS growing up, I don’t remember my parents talking about the stock market. In fact, I’m not sure when they started buying stocks. It could have been sometime after I graduated from high school in 1969.

When I was a junior in high school, however, I do remember a conversation about stocks between two of my classmates. Brandon was telling Brian that he could buy a motorcycle if he sold some of his shares.

I wasn’t surprised that Brandon owned stocks at the young age of 17. Both Brandon and Brian lived in Ladera Heights, California. It was a wealthy community back then and it still is today, with residents that include celebrities and highly paid sports figures. Some of my classmates from the area drove new Chevrolet Camaros, Plymouth Roadrunners and Ford Mustangs to school.

I never envied the Ladera Heights kids until many years later, when I wondered what happened to Brandon’s stocks. Did he still own them? Did he sell? Were they blue chip companies that are still trading on the stock exchange?

If he held on, just think how much those stocks might be worth today. All that compounding over many decades. At age 17, Brandon was sitting on a potential goldmine. But I suspect he sold long ago, displaying the sort of short-term focus that often hurts stock market investors.

Want to be more tenacious? Here are seven recommendations:

Invest in a target-date fund. You’ll have fewer decisions to make, and that’ll encourage a more hands-off approach to investing that can lead to better performance. According to BlackRock, target funds “may also soften the downside of tough markets—especially as retirement appears on the horizon.” The funds offer a diversified investment portfolio in a single mutual fund, with a stock-bond mix that grows more conservative as you approach retirement. The funds also continuously rebalance their asset mix—something investors often fail to do on their own.

Favor mutual funds over exchange-traded funds (ETFs). Yes, ETFs often have lower annual costs than index mutual funds. But they encourage frequent trading because their shares can be bought and sold whenever the stock market is open, while you can only trade a mutual fund once a day, as of the 4 p.m. ET market close. The legendary John Bogle once noted that turnover in the shares of SPDR S&P 500 ETF was 5,000% a year. “Is there anything the matter with that?” he pointedly asked.

Don’t invest in individual stocks. Prices of individual stocks can be highly volatile, making it harder to stay the course. Instead, invest in a target-date fund or a balanced fund, where share-price movements are less unnerving.

Turn off CNBC. Watching cable financial news can give you a short-term perspective on the stock market. The fixation on the minute-by-minute movement of share prices and interest rates, coupled with the commentary from financial pundits, can make your head spin.

Don’t listen to friends and family. Early in the 2000-02 bear market, I advised my sister to buy the dip, something I’ve long regretted, because it meant she bought at the beginning of a long ruthless downward spiral in stock prices. Where did I get that not-so-wonderful piece of advice? From an investment newsletter that I subscribed to at the time.

Don’t look at your investment portfolio. To be a tenacious investor, you need to take a long-term view of the stock market. Looking at the daily fluctuations in your portfolio’s value almost inevitably leads to emotional decisions.

If all else fails, get help from a low-cost financial advisor. Why pay for advice when you know how to manage your own money? What you know isn’t the only thing that matters. Instead, when it comes to investing, what also matters is how you behave. That’s one of the main reasons many investors underperform the market averages. With any luck, a good financial advisor will keep you from making costly behavioral mistakes—and, if you avoid those mistakes, the advisor’s fee could be money well spent.

Dennis Friedman retired from Boeing Satellite Systems after a 30-year career in manufacturing. Born in Ohio, Dennis is a California transplant with a bachelor’s degree in history and an MBA. A self-described “humble investor,” he likes reading historical novels and about personal finance. His previous articles include The Short Game, It Sure Adds Up and 11 Remodeling Tips. Follow Dennis on Twitter @DMFrie.

Dennis Friedman retired from Boeing Satellite Systems after a 30-year career in manufacturing. Born in Ohio, Dennis is a California transplant with a bachelor’s degree in history and an MBA. A self-described “humble investor,” he likes reading historical novels and about personal finance. His previous articles include The Short Game, It Sure Adds Up and 11 Remodeling Tips. Follow Dennis on Twitter @DMFrie.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation. Want to receive daily email alerts about new articles? Click here. How about getting our weekly newsletter? Sign up now.

The post Go Long appeared first on HumbleDollar.

October 13, 2020

A Seat at the Slots

WHAT DO HIGHER corporate profits truly mean to investors? Or, put another way, this 77-year-old neophyte wants to know, “How is investing in stocks different from gambling?”

Don’t get me wrong, I invest in stocks and I understand they’re the best way for most of us to grow wealthy over time. What I don’t get is, “Why? What causes a stock to increase in value?”

I’ve researched the question and what I find is a lot of talk about earnings per share, price-earnings ratios, earnings growth and such. But rather than answering my question, this stuff about earnings, valuations and so on leaves me even deeper in doubt.

One Sunday evening, I looked at the S&P 500 futures. They were up. But on Monday morning, the market tanked. What happened? Some news that had nothing to do with the value of any individual company, I suspect.

I own shares in my old employer. It’s a utility that’s been around for 110 years and pays a decent dividend. The stock price bounces around from day to day and yet nothing significant at the company changes. For the current quarter, analyst estimates of earnings per share range from $0.31 to $1.04. Should I be concerned? As long as the company pays its quarterly dividend—and continues to pay my pension—should I care about the latest quarterly earnings?

I’m told earnings, or the anticipation of higher earnings, drive share prices. But if I don’t get paid my share of those higher earnings as dividends, why pay more for the stock? Somebody is gambling, I think, but I’m not sure on what—except perhaps on higher price-earnings ratios.

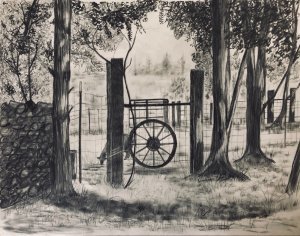

I tend to view the changing value of a stock like art. I’m an artist of sorts, albeit a mediocre one, as you’ll see from the picture below. But if I could get one critic (think analyst) to say a few kind words, someone might buy my art. Then some other sucker, I mean, investor might pay even more, and I’d be on my way.

Picasso and Rothko seem to have done well after a good word or two. How many people understand their art? Why buy a stock for many times its earnings when value seems to be in the eye of the beholder?

Picasso and Rothko seem to have done well after a good word or two. How many people understand their art? Why buy a stock for many times its earnings when value seems to be in the eye of the beholder?

On top of that, we have the difference between analysts’ earnings predictions and the actual results. A company meets, beats or doesn’t meet those quarterly estimates and the stock goes up or down. Why do we assume those analyst estimates are valid?

As I read an article about the best dividend-paying stocks for 2020, I scanned analysts’ opinions of each stock. One caught my eye. Four analysts had the stock as a “strong buy,” two as a “buy,” 12 “hold,” two “sell” and three “strong sell.” I guess they use different dice.

Increasing dividends are good. But many companies see their stock price rise, even though they pay no dividend. Investors are paying more for a stock because corporate profits are rising and yet those earnings aren’t getting shared. Yes, I get it, the earnings are being reinvested in the business, supposedly to enhance earnings down the road. But if that cash isn’t coming back to shareholders, why should I pay a higher price for the stock?

About those earnings: It doesn’t seem to matter how they increase. If earnings increase because sales are up and hence profits are up, that’s one thing. But if earnings increase because of workforce reductions or other cost cutting, that doesn’t impress me. Actually, it makes me wonder who was minding the store. How did the company get to the point where staffing and other costs were so out of control?

I read one explanation of rising stock prices that discussed the law of supply and demand. One person wants to sell and another is willing to pay more to buy. But why? Oh, I know, because earnings are expected to grow, so the stock will be worth more in the future. Isn’t that a circular argument?

While trying to figure all this out, I came across this: “[A] stock could… be considered overvalued if prices continue to rise, despite earnings falling short of predicted growth estimates. An overvalued stock is the opposite of an undervalued stock. When a stock is undervalued, it trades at a share price that’s below what the stock is actually worth. ”

Profound, right? So I guess I have to figure out what a stock is “actually worth,” and that seems to have something to do with “predicted growth estimates,” which doesn’t seem to have anything to do with putting cash in my wallet. My head is starting to hurt. How about just sending me a nice dividend check instead?

Richard Quinn blogs at QuinnsCommentary.com. Before retiring in 2010, Dick was a compensation and benefits executive. His previous articles include Want $870,000, Taking Credit and Do as I Don’t. Follow Dick on Twitter @QuinnsComments.

Richard Quinn blogs at QuinnsCommentary.com. Before retiring in 2010, Dick was a compensation and benefits executive. His previous articles include Want $870,000, Taking Credit and Do as I Don’t. Follow Dick on Twitter @QuinnsComments.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation. Want to receive daily email alerts about new articles? Click here. How about getting our weekly newsletter? Sign up now.

The post A Seat at the Slots appeared first on HumbleDollar.

October 12, 2020

Trading Places

MY WIFE AND I decided at the end of 2016 to sell our house. Selling a home is the biggest transaction most of us will ever make, and yet—in my experience—almost all home sellers spend too little time trying to find the right real estate agent.

Folks might interview two agents at most and many interview none at all, instead hiring based on a friend’s recommendation. I realized there must be a better way. Now, I didn’t know what that was, but I was determined to take a more rigorous approach. I had four options:

1. Full-service agent (a.k.a. “the 6% solution”)

We had used a full-service agent to buy our house. He hadn’t done a good job, so we interviewed three other full-service agents. All used what I came to realize is the classic (and only) real estate agent sales technique, which is to tour your house issuing generic compliments (“I love the natural light,” “beautiful floors” and so on) and then handing you “The Binder” which contains:

Brochures that tout their ability to sell your house, including abilities that every agent possesses: the multiple listing service (MLS), listing on Realtor.com, access to exclusive clientele, blah, blah, blah.

Agent bio.

Comps for your house that leads to the recommended sales price, which is the only thing you really care about.

None of the three agents made any effort to personalize his or her pitch. The phone call setting up the appointment, the compliments and The Binder were all identical. I kept waiting for something specific to our situation, but it never came.

One tip: Try to negotiate a 4.5% or 5% commission. While agents will obviously resist, some may agree, especially if it’s a higher-priced home.

2. Discount brokerage

There are some full-service brokerages that don’t charge a 6% commission. One of them is Redfin, which only charges a 1.5% selling commission. That means you still need to pay the 3% to the buyer’s agent. I had noticed one of Redfin’s for-sale signs in front of a house a block away from our home and contacted the agent. She showed up at the appointed time and proceeded to use the classic (and only) real estate agent sales technique. See above.

At one point, though, she mentioned that she knew the builder’s rep who sold us our home two years prior. I became filled with hope that she would next say that she had called him in an effort to gain a better understanding of how best to sell our house. My hopes were quickly dashed. She mentioned how Redfin would market our house using the MLS, listing on Realtor.com, access to exclusive clientele, blah, blah, blah.

3. Flat-fee listing service

There are brokerage firms that will list your house on the MLS for a flat fee, thus sidestepping the 3% selling agent’s commission. Generally, you’ll still have to pay a 3% commission to the buyer’s agent.

4. For sale by owner

Otherwise known as FSBO, this means not listing through the MLS, thereby avoiding both the 3% commission to the buyer‘s agent and the 3% selling commission. This is a true DIY option, but to me it isn’t a realistic option. Without the MLS, I’m not sure how you could get the exposure you need.

And the winner was… discount full-service brokerage. Actually, Redfin wasn’t so much the winner, but the best of the worst. While we weren’t impressed with the agent, she was no worse than the others and we were saving 1.5%.

Well, we met with our agent and agreed on a price of $424,900. As Houston was a buyer’s market, we needed to price the house above our expected selling price to allow for negotiation.

As soon as I saw the first draft of the MLS description that our agent had written, I knew we were going to have to work for our 1.5% in commission savings. The description was atrocious, almost like she had never written one before. My wife completely reworked it, turning it into the superior marketing document it needed to be.

On April 20, 2017, the for-sale sign was installed and we waited for the offers to come pouring in. And in a way they did. We were excited when Beverly Mae called us with an offer only a few days later. Our excitement quickly ebbed when we realized it was for $390,000.

The low-ballers had appended to their offer a lengthy document used to profess their ardor for our house. To be honest, I’m not sure of the entire contents, because I stopped reading their love letter after they stated that $390,000 was the best they could offer. Despite their instructions, we countered at $420,000. We never heard from them again.

A week turned into a month, a month into two months. We started dropping the price, first to $417,000 and then to $410,000.

In our subdivision, there was a larger house that was for sale for $575,000. As both our for-sale sign and theirs were at the entrance to the subdivision, we realized that many buyers that visited this larger house may not have realized our house was also for sale. We expressed our concerns to Beverly Mae, who was not concerned. At our insistence, she provided us with a second for-sale sign, which we installed on our front porch, in direct sight of those visiting the larger house. I wasn’t sure it was going to help, but it made me feel better.

After 100 days on the multiple listing service, the missus informed me I could get out of the fetal position. We had just received not one offer, but two. Our agent said that she had gone back to both buyers for their best and final offer. Buyer No. 1 responded with an offer of $400,000 and buyer No. 2 with an offer of $397,500. Our agent said the next step was for her to get a signed contract from buyer No. 1.

“Whoa, hold on a minute,” I replied and asked her to go back to buyer No. 2 and “tell her the bad news.” Beverly Mae was reluctant. She didn’t think this was professional, but she would if we insisted. We did and were rewarded with an offer of $405,000 from buyer No. 2.

“Next step is for me to get a signed contract,” said Beverly Mae, to which I replied, “Not yet, please tell buyer No. 1 the bad news.”

“If you insist,” she reluctantly replied. We did and were rewarded with a $410,000 offer from buyer No. 1. Unfortunately, after buyer No. 2 heard the bad news (again), she didn’t make a counteroffer.

“Well, I guess the next step is to get a signed contract,” I said to Beverly Mae, and she did.

We subsequently invited buyer No. 1 to our home to say “hello.” After a congratulatory toast, we were satisfied to learn that they had only noticed our home was for sale when they looked at our front porch—and saw the extra for-sale sign.

Michael Flack blogs at AfterActionReport.info. He’s a former naval officer and 20-year veteran of the oil and gas industry. Now retired, Mike enjoys traveling, blogging and spreadsheets.

Michael Flack blogs at AfterActionReport.info. He’s a former naval officer and 20-year veteran of the oil and gas industry. Now retired, Mike enjoys traveling, blogging and spreadsheets.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation. Want to receive daily email alerts about new articles? Click here. How about getting our weekly newsletter? Sign up now.

The post Trading Places appeared first on HumbleDollar.

October 11, 2020

Save and Give First

I’VE DISCUSSED the election in my recent articles and cautioned against timing the market. But if market timing isn’t recommended, what can you do to keep your finances on track through this potentially turbulent period?

Last week, I suggested reviewing your finances through the lenses of leverage, liquidity and cash flow. This week, I’d like to share another framework—and this is one you could employ at any time and not just in times of worry. Financial educator Brian Portnoy (not to be confused with day trader David Portnoy) offers this perspective: In the world of finance, he says, most of the discussion focuses on investments. While investing is important, it’s just one of seven dimensions of money that he sees as equally important. The other six are:

Earning

Giving

Saving

Spending

Borrowing

Protecting

I like this approach, but it isn’t necessarily easy. It requires each family or individual to find a balance among the seven dimensions. But how? I would start with the three areas that involve outflows—spending, saving and giving—since there’s a tradeoff among them. The other areas are also important, but they’re topics for another day.

1. Saving. In many—if not most—households, money is saved only after taxes are subtracted and the bills are paid. Ideally, however, you should budget for savings upfront. If you have a 401(k) or a similar employer-sponsored retirement plan, this is relatively easy because these plans make saving automatic. But if your employer doesn’t offer a retirement plan or you want to save more than your plan allows, how much should you earmark for savings? I would ask three questions:

How much do I need to save?

How much can I save?

How much do I want to save?

The answer to the first question is largely mathematical. If you can quantify the cost of your future goals, you can estimate how much you need to put away each month. The second question is even more mathematical: Given your income and expenses, how much are you able to save? The third question, on the other hand, is entirely personal. Some people love living frugally and enjoy saving—almost as an end in itself. Others take the opposite view: Why unnecessarily deprive myself if I don’t have to?

It may take some work, but these questions can be answered and that’s where I’d start—by deciding on a savings budget. I recognize that this may seem counter-intuitive since household savings budgets are usually just determined by what’s left over each month. And because paying the bills today is usually the priority, I also recognize that this approach may take time to implement.

2. Giving. Once you’ve determined your savings budget, I would move on to giving. Again, this may seem counterintuitive. For most people, charitable contributions are ad hoc and not formally budgeted. In some religions, there is a requirement to tithe—often 10%. That can make life easier because it’s very specific.

But if you aren’t working with any specific requirement, establishing a giving budget may be even harder than settling on a savings budget. Consider the three questions above. You don’t need to give any specific amount. Result? Your charitable budget is governed only by the amount you can afford and by the amount you want to give.

My advice: To come up with a giving budget, start with the amount you donated last year. Often, this can be found on your tax return. If cash flow permits, I would contribute that entire amount, all at once, to a donor-advised fund at the beginning of each year (or, if it helps for tax purposes, perhaps in December). Donor-advised funds carry a small cost, but they make charitable giving immeasurably easier to track and manage. On their websites, donor-advised funds will tell you at a glance how much you have put in and how much you have contributed to charities year-to-date. This makes it much easier to ensure you’re hitting your charitable goals each year.

3. Spending. For all but the most disciplined people, it’s awfully hard to formulate and stick to a household spending budget. That’s certainly the case in my house. But if you use the approach I’ve described above, I have good news: You don’t actually need a budget. If you’ve already set aside the amounts you’ll need for savings and for giving, you can—in theory—freely spend the remainder. Many people find this liberating.

When your income is limited, you have a pretty good idea of whether you can afford a specific purchase or not. But what if your income is higher and there’s more latitude in your budget? It can be hard to know where to draw the line.

In my work as a financial planner, I frequently hear this concern. The question normally sounds like this: “If a Tesla costs nearly six figures and I have the money, is it okay to buy one?” My answer is always the same: If you’ve set aside the amounts you need for saving and giving—and, of course, for the IRS—the answer is, “Yes, it’s okay.”

Adam M. Grossman’s previous articles include Don’t Play Politics, High Anxiety and When to Change

. Adam is the founder of

Mayport

, a fixed-fee wealth management firm. In his series of free

e-books

, Adam advocates an evidence-based approach to personal finance. Follow Adam on Twitter

@AdamMGrossman

.

Adam M. Grossman’s previous articles include Don’t Play Politics, High Anxiety and When to Change

. Adam is the founder of

Mayport

, a fixed-fee wealth management firm. In his series of free

e-books

, Adam advocates an evidence-based approach to personal finance. Follow Adam on Twitter

@AdamMGrossman

.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation. Want to receive daily email alerts about new articles? Click here. How about getting our weekly newsletter? Sign up now.

The post Save and Give First appeared first on HumbleDollar.

October 10, 2020

Game Over

LET’S START WITH the obvious: If you buy high-quality bonds today, you’ll collect very little yield—and there’s an excellent chance you’ll lose money once inflation and taxes are figured in.

Take Vanguard Total Bond Market ETF, which aims to track U.S. high-quality taxable bonds. It yields some 1.2%, which is below the 1.7% expected annual inflation rate for the next 10 years, and the amount you pocket will be even less after deducting taxes. In fact, high-quality bond yields are so low that investors can now earn more income by buying the broad U.S. stock market, though that, of course, would involve considerably more risk.

The bottom line: For now—and probably for the foreseeable future—bonds can’t play their No. 1 traditional role, which is to provide a healthy stream of income. That game is over, with big implications for how we structure our portfolios and how we think about our bond holdings.

While we can no longer get significant income from high-quality bonds, they could play two other potential roles in a portfolio. Role No. 2: Act as a diversifier for stocks, providing offsetting gains when stocks are suffering.

Vanguard Total Bond Market ETF—which has 59% in U.S. government bonds—has a slight negative correlation with Vanguard Total Stock Market ETF, which means it should provide modest gains when the U.S. stock market next tanks. Want even better bear market protection? As we were reminded earlier this year, the surest strategy is to focus solely on Treasury bonds.

But buying Treasurys as a diversifier for stocks creates a nasty dilemma. It isn’t simply that Treasury yields are tiny, with even 30-year bonds paying less than 1.6%. On top of that, if your goal is to have an investment that goes up sharply when stocks go down, you’ll need to head far out on the yield curve.

Let’s say you bought Vanguard Long-Term Treasury ETF. It has a duration of almost 19 years, which means it could soar 19% if interest rates dropped one percentage point during an economic slowdown—but you’d also lose 19% if interest rates head higher by one percentage point.

Not sure you could stomach that? You might go for something tamer, such as Vanguard Intermediate-Term Treasury ETF. It has a duration of five years, so you’re only looking at a 5% gain or loss on a one percentage point move in interest rates. Problem is, a 5% gain wouldn’t do much to salve your investment wounds if the economy slowed, stocks tumbled and interest rate fell by one percentage point.

Like everybody else, I have no idea where interest rates are headed from here, so there’s no point in playing market prognosticator. That said, we can think about short-term risk—and I’m not sure many of us would be happy with the gain vs. loss tradeoff offered by intermediate and long-term Treasurys, especially when the net result over the life of these bonds will be a negative after-tax, after-inflation return.

The upshot: We can’t expect bonds to fulfill their traditional income-generating role—and I’m not sure the tradeoff is all that attractive if we buy them as a diversifier for stocks. That leaves us with role No. 3: Hold bonds as a backup source of cash if it’s a bad time to sell stocks.

If that’s our reason for owning bonds, we might still stick with government securities—but instead of plunking for the long-term Treasurys that’ll potentially deliver big upside gains when stocks next suffer, we might go for short-term bonds. That way, we’re taking very little interest rate or credit risk, and thus—if we need cash from our portfolio—we can be confident our bonds should be worth pretty much what we paid, no matter what’s going on in the world.

In other words, I’d stop thinking of bonds as a source of yield or as a diversifier for stocks. Instead, think of them as way to generate cash if the stock market is in the toilet. How much should you have in short-term government bonds? It depends on three key factors:

Whether you’re working or retired. As an emergency fund, those who are working might keep three-to-six months of living expenses in short-term government bonds or, alternatively, in super-safe cash investments like savings accounts and money market funds. If your job is at risk, go for the full six months. Meanwhile, if you’re retired or near retirement, you might calculate how much you need from your portfolio over the next five years and keep that sum in conservative investments.

Whether you have big onetime expenses coming up in the next five years. Those expenses—your teenager’s college tuition, the money for the new roof, the down payment on a new house—should also be in short-term bonds or cash investments.

How much risk you can tolerate. If you find stock market declines unnerving, you might keep additional money in short-term government bonds. How much more? It depends on how much you need in conservative investments to stay calm when the stock market next plummets.

The overriding goal: You should be able to look at your portfolio and say to yourself, “No matter what happens to my stocks in the short term, I’m happy to hang on to them, because I have the money I’ll need to spend in the near future sitting in safe investments.”

Suppose you’re retired, with five years of portfolio withdrawals in short-term government bonds and cash investments. You know that, if stocks plunge, you have five years before you’ll be compelled to sell stocks to buy groceries. That should be enough time for the stock market to recover.

That’s how I view the bonds in my portfolio. As someone near retirement age, I have enough in short-term government bonds to cover my expected expenses in the years ahead. That frees me up to invest the rest of my portfolio in stocks—and, fingers crossed, those stocks will deliver results that compensate for the wretchedly low return on my bonds.

Latest Articles

HERE ARE THE SIX other articles published by HumbleDollar this week:

“Thankfully, there’s a tipping point” when saving for retirement, says Sanjib Saha. “Soon enough, the annual investment growth of our nest egg should surpass our annual savings, encouraging us to keep at it.”

Should you buy a whole-life insurance policy for your kids to guarantee coverage, even if their health later deteriorates, and to jumpstart their retirement savings? Dennis Ho runs the numbers.

“I don’t know how much longer I have on this planet, but I would happily trade dollars for time—more time helping clients solve their problems and more time playing with my kids while Dad is still cool,” writes John Goodell.

Do friends and family ask you for investment advice? Here’s what Sonja Haggert says.

“We saved our whole life to get where we are,” notes Dennis Friedman. “We’re going to make sure we enjoy the rest of our life as best we can. If that means spending down our retirement savings, so be it.”

Are you ready for rough financial times? Adam Grossman advises examining your finances the way an analyst would examine a bond—by taking a close look at your family’s leverage, access to cash and cash flow.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter @ClementsMoney and on Facebook. His most recent articles include Pay It Forward, Not Exactly True and Seems So Easy.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter @ClementsMoney and on Facebook. His most recent articles include Pay It Forward, Not Exactly True and Seems So Easy.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation. Want to receive daily email alerts about new articles? Click here. How about getting our weekly newsletter? Sign up now.

The post Game Over appeared first on HumbleDollar.

October 9, 2020

Stop and Go

LIKE SO MANY others, I’ll be working from home for the foreseeable future. But I know in my soul that we’re all going back—and I’m mostly okay with that. There are things I miss about the office: colleagues who have become friends, the collaboration, the access to ideas and creativity.

The biggest thing I don’t miss? Traffic. Nothing even comes close.

I live in Austin, Texas, which ranks tenth in America in terms of worst commute. My first thought when I read these rankings is, “How is Austin not No. 1?” My second thought is, “Who could stand living in these other, even worse concrete parking lots?”

Pre-pandemic, Austinites spent 104 hours a year stuck in traffic. That’s more than four days each year spent stopping and starting… over and over again. In total, the average Austinite spends roughly half a year mired in traffic during his or her working life. Because we chose our home by considering multiple factors—real estate costs, my wife’s work location, good schools for our kids—my commute works out to about 4.5 times that amount, and I live in a nearby suburb.

On top of that, my commute meant I was having to fill up on gas twice each week, devouring roughly 20 minutes per week. (Americans spend an average 10 minutes on each trip to the gas station.) That works out to some 17 hours per year spent pumping gas.

Those are wasted hours that I’m not with family or being productive at work. I boost my productivity from zero to something slightly above zero by listening to books on tape or podcasts, but there’s no substitute for being with my family or helping clients. Moreover, when I arrive at my destination, I’m irritated—and often sweaty—from sitting in traffic purgatory.

So I bought a Tesla Model 3 with self-driving. Let me be clear: I own the car, not the stock. I am a devotee of index funds and offer no opinion on the Tesla stock market bubble, I mean, phenomenon. That said, the Model 3 is an incredible machine. There are several vehicles available from Tesla, but the Model 3 is the least expensive. The long-range, 322-mile battery version costs roughly $47,000 today before taxes, plus $8,000 for full self-driving. That’s more than the $5,000 I paid for self-driving 18 months ago. Moreover, the tax credit I received is long gone. But even with these cost increases, I’d still buy one today.

Used Model 3s are now fairly readily available, but that wasn’t the case 18 months ago, so I bought mine new. As someone who is very frugal—my habit of primarily buying gently used shoes has earned me the moniker “tightwad” in our house—this might seem like an uncharacteristically lavish purchase. It was and it wasn’t.

I calculate that the purchase cost will eventually be offset by the amount I save by charging the vehicle instead of buying gas. Admittedly, the economics of owning a Tesla are widely debated and, in any case, had nothing to do with my decision to purchase one.

So why did I buy it? Whenever we return to the office, I’ll return to my much-hated commute. Enabling Tesla’s self-driving feature means the car does almost all of the work. I arrive at home or the office rested, rather than exhausted and irritated. Because we installed a charger in our garage, which cost just under $1,000, I leave each morning with a full charge and never have to waste those 10 minutes filling up at the gas station. Finally, our electricity comes from a solar-only utility, which means we pay a little more, but I enjoy the mental benefit of using zero carbon to commute.

The only lamentable irony: This machine is so incredible and so popular that Tesla is expanding—to Austin. The influx of jobs will be great for our local economy, but it’ll undoubtedly make my commute even worse.

Each reader will have his or her opinion on what a car should cost. That’s as it should be, because personal finance is just that: personal. I don’t know how much longer I have on this planet, but I would happily trade dollars for time—more time helping clients solve their problems and more time playing with my kids while Dad is still cool. (The teen years are almost upon us, so that moment will soon pass.) Yes, it sets back my journey to financial independence a little. But I’m good with that.

John Goodell is a government attorney who has spent much of his career advocating for military and veterans on tax, estate planning and retirement issues. His biggest passion is spending time with his wife and kids. Follow John at HighGroundPlanning.com and on Twitter @HighGroundPlan. His previous articles include My Five Truths, At Ease and Income Isn’t Wealth. The opinions expressed here aren’t necessarily those of the U.S. government.

John Goodell is a government attorney who has spent much of his career advocating for military and veterans on tax, estate planning and retirement issues. His biggest passion is spending time with his wife and kids. Follow John at HighGroundPlanning.com and on Twitter @HighGroundPlan. His previous articles include My Five Truths, At Ease and Income Isn’t Wealth. The opinions expressed here aren’t necessarily those of the U.S. government.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation. Want to receive daily email alerts about new articles? Click here. How about getting our weekly newsletter? Sign up now.

The post Stop and Go appeared first on HumbleDollar.

October 8, 2020

Neglected Child

I GREW UP IN INDIA, where I worked for a few years before venturing overseas and finally emigrating to the U.S. In our culture, most parents feel responsible for their children until their offspring are fully settled in their career and their life, which is often well into adulthood. In turn, the children feel dutybound to support their parents in old age, financially and otherwise.

This cultural tradition is mutually beneficial when both parents and children can fulfill their respective responsibilities. I’m forever grateful that I could start my career without the burden of student loans. Education costs are considered a parental responsibility in our culture, and my parents happily took care of those costs for both my brother and me.

Meanwhile, my parents quit sweating over their retirement readiness once my brother and I were settled in our career. Though they decided to continue living in India, they knew they could count on us to support them in old age. As it turned out, thanks to my father’s generous pension and lifelong health care benefits, my parents were financially independent in retirement and needed no monetary help from my brother and me. But our unstated commitment was surely a source of comfort to our parents.

This culture of generational interdependence, however, doesn’t always work out. Consider my distant cousin, whom I’ll call Ratan. Ratan fell short of his parents’ expectations when it came to their needs in old age. But it wasn’t entirely his fault.

When Ratan was young, his father was absorbed with other matters, including running his own business. He had little time for anything else. That meant Ratan didn’t get the ongoing attention he badly needed. He struggled in school. His high school grades were too poor to secure a place at a good college.

Ratan could have used more parental guidance. By the time his dad started paying more attention, it was too late to make much difference. As a grownup, Ratan ended up in unstable and low-skill jobs. His meager income was barely enough to support himself, let alone his parents.

Why am I telling you about all of this? I see parallels between neglected children like Ratan and our own often-lackadaisical attitude towards retirement savings. Since most of us will depend on those savings to support us in old age, we should feel dutybound to care for our nest egg’s wellbeing, in the same way we care for our children. If we did that, we could reap five benefits:

1. We wouldn’t procrastinate. Even before a child is born, parents start spending time, energy and resources on their future offspring. Our feelings of affection and responsibility spur us to action.

If we applied the same attitude to retirement savings, we’d act as soon as we started our career and got our first paycheck. Those paychecks won’t last forever and, as the years pass, other competing priorities begin taking a bite out of our income. Result? We’d realize that procrastination is not an option.

2. We’d focus on early development. Learning and changing is easier when children are younger. Catching up later may be possible, but it grows more difficult.

The same principle applies to retirement savings. The compounding enjoyed by our initial savings has a profound effect on our retirement fund. Take the example of a 22-year-old who starts stashing $200 per month in a retirement fund and continues at that level, adjusted for inflation, until age 67.

Assuming a 6% after-inflation annual growth rate, those contributions eventually grow to more than $500,000, figured in today’s dollars. But more than a quarter of that final stash comes from the first five years of savings, while the first 10 years account for nearly half. In other words, the savings from the last 35 years has barely more impact than the first 10 years of contributions.

3. We’d gather the information we need and muddle through. Parenting is hard, but it doesn’t require an advanced degree or fancy credentials. Most people learn from common sense, experience, friends and family, and readily available information.

Similarly, taking care of retirement savings involves nothing more than common sense and basic financial literacy. Help is plentiful. It’s certainly hard to be disciplined and stay on course, but it doesn’t require a PhD in finance.

4. We would show more patience. Kids don’t grow overnight. They need ongoing care and support for a long time. When we sign up our kids for swimming lessons, we don’t expect them to be budding Olympians the following week.

Saving for retirement is no different. It takes time, patience and tenacity. We need to monitor how our retirement fund is growing and whether things are on track. Thankfully, there’s a tipping point when the results of our hard work become visible. Soon enough, the annual investment growth of our nest egg should surpass our annual savings, boosting our morale and encouraging us to keep at it. Take the example above of our 22-year-old. By age 35, the annual growth of the money already saved starts to exceed the sum socked away each year.

5. We’d grasp the richness of the reward. Most parents get great joy from watching their kids grow and guiding them through new experiences. It’s a long journey that brings enormous satisfaction. Similarly, financial freedom—the ability to live life on our own terms—can take years to achieve, but both the journey and the goal can be hugely satisfying.

On the flip side, negligence is costly. Neglecting a child’s needs eventually hurts everyone involved. Likewise, neglecting our future financial wellbeing almost never ends well.

A software engineer by profession, Sanjib Saha is transitioning to early retirement. His previous articles include Fatal Attraction, Identity Crisis and Triple Blunder

. Self-taught in investments, Sanjib passed the Series 65 licensing exam as a non-industry candidate. He’s passionate about raising financial literacy and enjoys helping others with their finances.

A software engineer by profession, Sanjib Saha is transitioning to early retirement. His previous articles include Fatal Attraction, Identity Crisis and Triple Blunder

. Self-taught in investments, Sanjib passed the Series 65 licensing exam as a non-industry candidate. He’s passionate about raising financial literacy and enjoys helping others with their finances.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation. Want to receive daily email alerts about new articles? Click here. How about getting our weekly newsletter? Sign up now.

The post Neglected Child appeared first on HumbleDollar.

October 7, 2020

Covering Kids

TERM INSURANCE is typically the best bet for people who need life insurance, while permanent policies are appropriate for relatively few folks. Yet I keep getting the same question from parents: What about children? Does it make sense to purchase a whole-life policy for a young child?

No doubt influenced by Gerber Life Insurance’s relentless marketing, these parents want to know whether it’s worth locking in insurance pricing early on and whether this is a good way to help their children start saving for retirement. Intrigued? Here’s a framework to help you evaluate the pros and cons.

To see whether a whole-life policy is a good way to lock in life insurance costs, consider a hypothetical example. Let’s say parents of a 10-year-old girl—we’ll call her Katelyn—believe she’ll need $500,000 of life insurance once she reaches age 35 and potentially has a family who depends on her financially. One possible strategy: Purchase $500,000 of whole-life insurance for Katelyn today to guarantee she’ll have coverage later on.

The best price I could find for this coverage was a premium of $2,040 per year, payable for life. By the time Katelyn reaches 35, she and her family will have paid 25 years of premiums, totaling $51,000, and will be required to continue paying that $2,040 every year for the rest of her life. By contrast, if she waits until age 35 to purchase a 30-year term policy, the cost today is $370 per year for a 35-year-old woman in the top health class (super preferred) and $675 if she’s of average health (standard).

In other words, despite locking in pricing 25 years earlier, the whole-life policy will still be three to five times more expensive than the average 30-year term policy for Katelyn at age 35. Even if Katelyn has some major health issues in the future, it would be difficult for the premium on a 30-year term policy to exceed the $2,040 per year of the whole-life policy, let alone offset the $51,000 of past whole-life premiums.

I tested this with a few other scenarios and the results were similar. If your goal is to ensure that your child has access to life insurance in the future, purchasing a whole-life policy at a young age is an expensive way to do it. Yes, there’s always a chance that your child has health issues that means life insurance isn’t available at all. But when comparing the odds of that situation to the $51,000 of premiums in the scenario above, I’d argue most people are better off skipping the whole-life policy. Many of you will rightly point out that comparing whole life to term isn’t completely fair, given the opportunity to build up cash value in the whole-life policy. That brings us to our second topic: Is whole life a good way to help a young child save for retirement?

Using the quote for Katelyn at age 10, we can look at how the cash value of her policy builds up over time. With whole life, you have a minimum guaranteed cash value at each age, plus you also receive annual dividends based on the performance of the insurer’s life insurance business. In general, higher interest rates will lead to more investment income, which increases dividends. Lower interest rates will do the opposite. Similarly, fewer-than-expected death claims will increase dividends and higher death claims will reduce them.

The upshot: With a whole-life policy, you’re participating in the performance of the insurer’s business, but have a minimum guaranteed cash value to protect you if things go badly. Let’s say Katelyn’s parents want to build cash value in the whole-life policy up to age 65, at which point they expect her to use the cash value to cover retirement expenses or, alternatively, to purchase an income annuity or long-term-care insurance.

In the quote we got for 10-year old Katelyn, the insurer guaranteed cash value of $214,175 at age 65. That was after total premium contributions of $112,200 over 55 years. Using Excel’s nifty internal rate of return (IRR) formula, this translates into a guaranteed annual return of 2.2%. The quote also included an estimated non-guaranteed cash value at age 65, assuming dividends continue based on the insurer’s current dividend scale. This value was $521,026, producing an IRR of 4.8%. Actual cash values will certainly be different from this projection, but the $521,026 is a good proxy for what you might expect to earn on such a policy.

An expected IRR of 4.8% and a minimum IRR of 2.2% doesn’t sound too bad in today’s environment, especially compared to other investment options. But there are caveats. First, the whole-life policy is highly illiquid, meaning to get these returns, you need to hold it until age 65 and can’t make any changes to the premiums you pay. Second, your return is driven by the performance of a block of life insurance business. That might not be a risk everyone is comfortable with. Finally, you’ll be exposed to a single insurer—and the risk that it may fail—for many decades.

I suspect folks who are comfortable investing their funds in the stock market or other higher-yielding asset classes won’t find these whole-life returns attractive. But for those who want a simple investment and are comfortable with the caveats above, I’d contend the whole-life policy wouldn’t be a terrible way to put away some money for Katelyn. But because of the caveats above, I would limit the allocation to less than 15% of Katelyn’s savings.

This is not a blanket recommendation. Don’t assume that Katelyn’s numbers apply to all whole-life policies for children—and, based on the pricing I’ve seen, investigate policies other than Gerber Life, which I’ve found to be expensive. Before finalizing any purchase, make sure you review any quotes to confirm the guaranteed and expected returns under the scenarios you care about. Need help reviewing a quote or calculating IRRs? Shoot me an email at the address below.

Dennis Ho is a life actuary and chief executive of Saturday Insurance, a digital insurance advisor that helps people shop for life, disability and long-term-care insurance, as well as income annuities. Prior to co-founding Saturday, Dennis spent 20 years in the insurance industry in a variety of actuarial, finance and business roles. His previous articles include No Down Less Up, Questions I’m Asked and Retire That Policy. Dennis can be reached at dennis@saturdayinsurance.com or via LinkedIn. Follow him on Twitter @DennisHoFSA.

Dennis Ho is a life actuary and chief executive of Saturday Insurance, a digital insurance advisor that helps people shop for life, disability and long-term-care insurance, as well as income annuities. Prior to co-founding Saturday, Dennis spent 20 years in the insurance industry in a variety of actuarial, finance and business roles. His previous articles include No Down Less Up, Questions I’m Asked and Retire That Policy. Dennis can be reached at dennis@saturdayinsurance.com or via LinkedIn. Follow him on Twitter @DennisHoFSA.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation. Want to receive daily email alerts about new articles? Click here. How about getting our weekly newsletter? Sign up now.

The post Covering Kids appeared first on HumbleDollar.

October 6, 2020

Friend Requests

MY HUSBAND AND I have been investors for a long time. For us, it’s an interesting hobby and we’ve learned a lot along the way, plus we’ve made some money.

Friends and family sometimes ask what we’re doing and whether we can help them. Neither of us has any sort of certification as a financial advisor or any sort of formal training in investments. We can just imagine what a wrong suggestion would do to a friendship or family relationship.

Instead, we share our thoughts and philosophy in general terms, and shy away from naming specific investments. Here are five points we make:

1. Get a financial education. Read The Wall Street Journal. It’s the gold standard for financial information and highly readable. Check out CNBC’s Mad Money for its interviews with corporate executives, and also Squawk Box, which tends to be more issue-oriented, with big name guests such as Alan Greenspan and Bill Gates.

YouTube has a variety of options, including a popular channel for Millennials called The Financial Diet. The choices in books are vast. We enjoyed The Gone Fishin’ Portfolio by Alexander Green, which encourages diversification with a selection of mutual funds and exchange-traded funds (ETFs). If you’re like us and interested in dividend stocks, you might also enjoy Marc Lichtenfeld’s Get Rich with Dividends.

The investing forums on Reddit and Quora are great for asking questions. We constantly refer to Seeking Alpha and Atom Finance for general market information, and head to Yahoo Finance and Fidelity Investments for information on specific investments. Vanguard Group has a wonderful tool that lets you compare mutual funds and ETFs, even those not managed by Vanguard. For dividend investors, DRIPInvesting.org is an excellent resource, while MarketBeat.com is good for information on dividend increases and decreases.

2. Think hard about your goals. It really pays to have some basic understanding of where you want to go on your financial journey and how gentle you want the ride to be, because your time horizon and risk tolerance will have a big influence on how you invest. While retirement is the ultimate goal, perhaps you have interim goals such as a college education for a child or a second home.

3. Diversify broadly. You should probably have the bulk of your money in mutual funds or ETFs, which are a simple way to get exposure to hundreds or even thousands of different securities. My husband and I favor ETFs. Why? Mutual funds will, in almost all cases, have higher fees, plus they tend to generate bigger tax bills.

4. Hire a financial advisor. I realize that not everybody needs a financial advisor. But even though we feel we’re reasonably knowledgeable about investments, my husband and I have an advisor. He’s a good sounding board, and he helps us stick to our financial plan and revise it when necessary.

How do you find an advisor you can trust? Get recommendations from your tax advisor, attorney or other professionals with whom you have dealings. You might also ask friends. Make sure potential advisors have meaningful credentials, such as the Certified Financial Planner or Chartered Financial Analyst designation. You can check out an advisor’s credentials at Finra.org. Then interview your choices. Some questions you might ask:

How will I pay for your advice? Do you charge a percent of assets or an hourly fee, or are you on commission? How much can I expect to pay each year?

What types of investments are you licensed to sell?

How often will you communicate with me? You should expect to talk to your advisor—either in person or on the phone—at least every six months.

Ask potential advisors to explain a concept with which you’re familiar. See if the explanation is clear or condescending. You want to deal with someone who speaks your language, not jargon.

Ask potential advisors about the last financial mistake they made and how they handled it.

Make sure the advisor you pick is someone you feel comfortable with and who understands your goals. If it just doesn’t feel right, or if the advisor speaks only to you and not to your partner, look elsewhere.

5. For my husband and me, the fun part of investing is following companies that interest us. For instance, you might keep tabs on Apple because you like its iPhone or Teladoc because you’re a doctor. Just don’t imagine that because, say, you’re a software engineer or a physician that you have some special insight. Indeed, if you decide to buy individual stocks, don’t invest in a company just because you work in the same industry, or you got a tip from a friend, or you heard someone rave about the stock on TV.

Instead, get help from your financial advisor or from a financial newsletter. To find a newsletter that resonates with you, ask for sample copies. We subscribe to one that matches our philosophy. The biggest benefit is that the newsletter does the financial analysis for us. So what’s our philosophy? We like dividend-paying stocks, especially those that have a history of regularly raising their dividend. Reinvesting those dividends can be a great way to benefit from investment compounding.

Sonja Haggert’s previous articles were Right Turn, Getting Used and Check’s in the Mail. She’s the author of Invest, Reinvest, Rest. You can learn more at SonjaHaggert.com. Follow her on Twitter @SonjaHaggert.

Sonja Haggert’s previous articles were Right Turn, Getting Used and Check’s in the Mail. She’s the author of Invest, Reinvest, Rest. You can learn more at SonjaHaggert.com. Follow her on Twitter @SonjaHaggert.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation. Want to receive daily email alerts about new articles? Click here. How about getting our weekly newsletter? Sign up now.

The post Friend Requests appeared first on HumbleDollar.

October 5, 2020

The Short Game

I WOKE UP one morning, looked in the mirror and didn’t recognize the person looking back at me. Who is this person? It can’t be me. I’m not the same person I was five or six months ago. I don’t know if it’s the pandemic that caused me to behave differently or if I’m going through some kind of midlife crisis.

No, it can’t be a midlife crisis. I’m almost 70 years old, plus I don’t feel my life is boring, empty or meaningless. In fact, I actually feel good about myself and my life.

Instead, what I don’t understand is why I have a different attitude toward money. All my life, I’ve been a supersaver. It was the main reason I was able to retire early. It sure wasn’t because of my investing skills. I was, at best, just an average investor. But recently, I’ve been spending gobs of money in ways I never would have in the past.

I’m doing a complete remodel of my house. Of course, some of the work needed to be done, but not everything. If it didn’t involve a mountain of building permits and other paperwork, I’d probably have added on to the house, too. Oh, did I tell you I bought all new appliances and furniture for the house? If I were my younger self, I would say it was wasteful spending. But I’m not my younger self anymore. I’m someone else.

I’m not just spending money on the house. I bought a car and I’m planning to buy another vehicle later this year. If it weren’t for COVID-19, I would be on my way to Europe for a month or two. In fact, I charged so much on my credit cards that I received a notice my credit score has dropped. I don’t care. That won’t stop me from spending.

I got a list of things I want to see and do when this pandemic is over. It’s going to take more money, but I’m not stressed about it. I’ve got all these retirement accounts to finance my new spending habit: a traditional IRA, rollover IRA, Roth IRA and an old 401(k). And don’t forget Social Security, which will kick in next year at age 70.

It’s baffling. I don’t know what suddenly brought on this impulse to spend without hesitation, but I have no regrets about it. My wife is right there with me, spending left and right, so it can’t be just me going through some sort of crisis. She, like me, was always a cautious spender. In fact, that’s one of many reasons we get along so well.

I have a theory about why I’m behaving the way I am. When you’re young, you play the long game. You save and invest for your future, knowing you may live another 40 or 60 years. But when you’re older, you play the short game. Your timeline is condensed and you’re more willing to spend down your savings to live an enjoyable and comfortable retirement. I’m playing the short game. I’m in spending mode.

There’s no reason my wife and I should adhere to our past behavior of saving and pinching pennies for the future. The future is now. Why not spend in a way that’ll allow us to enjoy life to the fullest? We have no family obligations, except for a son who doesn’t need our financial help. Still, we’re planning to leave him some money.

We saved our whole life to get where we are. We aren’t irresponsible spenders aiming to die penniless, but we’re going to make sure we enjoy the rest of our life as best we can. If that means spending down our retirement savings, so be it.

Dennis Friedman retired from Boeing Satellite Systems after a 30-year career in manufacturing. Born in Ohio, Dennis is a California transplant with a bachelor’s degree in history and an MBA. A self-described “humble investor,” he likes reading historical novels and about personal finance. His previous articles include It Sure Adds Up, 11 Remodeling Tips and Trust but Verify. Follow Dennis on Twitter @DMFrie.

Dennis Friedman retired from Boeing Satellite Systems after a 30-year career in manufacturing. Born in Ohio, Dennis is a California transplant with a bachelor’s degree in history and an MBA. A self-described “humble investor,” he likes reading historical novels and about personal finance. His previous articles include It Sure Adds Up, 11 Remodeling Tips and Trust but Verify. Follow Dennis on Twitter @DMFrie.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation. Want to receive daily email alerts about new articles? Click here. How about getting our weekly newsletter? Sign up now.

The post The Short Game appeared first on HumbleDollar.