Jonathan Clements's Blog, page 309

October 24, 2020

Irksome Adversaries

WE FIGHT ABOUT money all the time. Politicians argue over how to spend the stuff and who should pay. Couples argue about why there isn’t enough and who’s to blame. And nerdy folks—that would include me—bicker over which investments to buy, when to claim Social Security, the virtues of homeownership and countless other topics.

These debates may amuse others, but I often find them frustrating—because they’re never just about facts and logic. Instead, far too many people come to these arguments with baggage that borders on cargo. Below are the four groups of folks you never want to debate. We’re talking here about financial topics, but (dare I mention this?) the same holds true for politics:

1. Those enamored of anecdotal evidence. As experts in behavioral finance often note, we’re much more likely to be won over by a good story than a compelling statistic.

An example: Whenever I question the virtues of cash-value life insurance, I’ll often hear from insurance agents who recount touching tales of delivering fat checks to grieving widows. But this is an intellectual non-sequitur: The fact that these agents have delivered checks to widows doesn’t clinch the case for cash-value life insurance. Term life insurance would also have paid these widows a death benefit—and, in fact, they might have received a much larger check, because they could have afforded more coverage, given term insurance’s far smaller premiums.

Similarly, fans of active management will point to Warren Buffett, who does indeed have a fabulous 56-year record. But so what? The fact that somebody somewhere won the lottery is hardly a compelling argument for buying lottery tickets in general, nor does it mean you should find the lottery winner and ask him or her to buy tickets on your behalf.

To be fair, we all know (I hope) that the lottery involves no skill, whereas Buffett has—I believe—proven that he has astonishing skill. But the point still holds. Over the years, many money managers have appeared skillful. But if you’d taken that as a sign you should invest with these money managers, you usually would have been disappointed, as their hot hand turned cold. Even Buffett’s results have been relatively pedestrian over the past decade, though that’s hardly surprising, given the many billions he now oversees.

2. Those with a financial incentive. Why do financial advisors who sell customized portfolios decry target-date retirement funds? Why do insurance agents insist cash-value life insurance, variable annuities and equity-indexed annuities are great investments? Why do active managers belittle index funds and depict them as somehow evil? Why do so many employees of full-service brokerage firms dismiss everyday investors as stupid—and persist in pushing the deeply flawed Dalbar study?

These aren’t exactly trick questions. We all know why: These folks have a financial incentive to take the positions they do. As Upton Sinclair said, “It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends upon his not understanding it.”

Financial incentives are hugely powerful. Alas, they also infect the financial blogging community. Many bloggers have affiliate marketing relationships with, say, money management firms and credit card companies, which means they make money if readers click through and open an account. This inevitably influences what they write. HumbleDollar used to have some affiliate marketing relationships, but we no longer do. We don’t want readers to worry that we’re running articles so we can make money at their expense.

3. Those who have already cast their vote. Those who own rental properties are often vocal advocates of investing in rental real estate. Those who claimed Social Security early will argue vociferously that all retirees should take benefits at age 62. Those who own individual bonds will often pooh-pooh bond funds.

I think these folks are wrong—and that most people should delay Social Security and stick with bond funds, rather than individual bonds. Meanwhile, I’m leery of rental properties, because it’s a big undiversified bet and potentially a lot of hassle.

But mostly, I’m wary of folks hellbent on justifying what they themselves have already done. Instead, I’d much rather hear from those who have changed their mind, because their new opinion is often the result of anguished self-reflection.

4. Those stuck in the past. As the financial world changes, we need to change with it—but many folks resist tooth and nail. In late June, I discussed four fundamental financial changes that have occurred during the time I’ve been writing about money, including a drastic reduction in the value of the mortgage tax deduction and what appears to be a permanent shift upward in stock market valuations.

Yet many folks simply can’t escape the past. That’s left them sitting on the sidelines as stocks have climbed over the past three decades, while also carrying mortgage debt that’s delivering little or no tax advantage. We need constantly to question our financial beliefs. Some beliefs, like the virtue of holding down investment costs, diversifying broadly and insuring against unbearable financial risks, will endure. But others are less timeless—which means that as the financial world changes, we must, too.

Indeed, we should ask not only whether we’re acting on outmoded financial beliefs, but also whether we’re too influenced by anecdotal evidence or too invested in our earlier financial decisions. It’s bad enough arguing with an adversary who ignores fact and logic. But it’s even worse when that enemy is us.

Latest Articles

HERE ARE THE SIX other articles published by HumbleDollar this week:

“The fact that a few investors—maybe including your annoying neighbor—beat the averages is just a statistical necessity,” notes Bill Ehart. “Someone or something has to be top decile in any data set.”

Kristine Hayes and her husband went hunting for a retirement home that checked all their boxes: price, health care, taxes, recreation, weather and more. They found it outside Phoenix, Arizona.

The last major rewrite of the tax code was just three years ago—but the next one may be right around the corner. James McGlynn looks at the potential changes that are in the offing.

The Federal Reserve recently revised its “constitution.” That might sound arcane—but it has seven key implications for investors, says Adam Grossman.

“He reminded us that most people in this world do not pass away surrounded by their loved ones and the people they trust the most,” writes Anika Hedstrom. “We should all be so lucky when our time comes.”

Planning to relocate when you retire? Rick Connor’s advice: Check out a state’s property, sales, estate and income taxes—including whether Social Security, pensions and IRAs are taxed.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter @ClementsMoney and on Facebook. His most recent articles include Where We Stand, Game Over and Pay It Forward

Follow Jonathan on Twitter @ClementsMoney and on Facebook. His most recent articles include Where We Stand, Game Over and Pay It Forward

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation. Want to receive daily email alerts about new articles? Click here. How about getting our weekly newsletter? Sign up now.

The post Irksome Adversaries appeared first on HumbleDollar.

October 23, 2020

The Taxman Cometh

LATE LAST YEAR, Congress voted to kill off the so-called stretch IRA, which had allowed those who inherited retirement accounts to draw them down slowly over their lifetime. Many folks were surprised by the stretch IRA’s demise, but they shouldn’t have been.

When a tax break or some other government provision benefits only a few folks, Congress often changes the law. Think back to 2015. That year, Congress eliminated the ability to “file and suspend” Social Security—another strategy that tended to be exploited only by a privileged few.

I suspect we’ll see similar Congressional action in the years ahead.

This election season, there’s been talk of reversing the tax rate reductions in 2017’s Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), especially for those who’ve benefited the most from those cuts. In any case, after year-end 2025, many of the TCJA changes sunset. The upshot: If Congress doesn’t act in the next five years, taxes will automatically increase. But it isn’t just the TCJA that’s in the political crosshairs. Here are five other key areas where we might see changes to the tax code:

There’s discussion of eliminating the preferential long-term capital gains and qualified dividend tax rates for those with incomes above $1 million. Warren Buffett has often complained that he pays a lower tax rate than his secretary. This change would ease his conscience by boosting the capital gains and dividend tax rate from 20% to potentially 39.6%, but only for those with seven-figure incomes.

The TCJA reduced corporate tax rates from 35% to 21%. There are proposals to increase that rate to 28% and to ensure all corporations pay a 15% minimum tax.

I predict that, at some point between now and 2034, there’ll be changes to the payroll tax that funds Social Security or, alternatively, that other federal revenues will be used to support the program. If not, we could face a 20% cut in Social Security benefits due to a lack of funding—and the fact is, there are simply too many seniors who rely on Social Security as their main source of retirement income. In 2020, workers pay Social Security payroll tax on their first $137,700 of earnings. One proposal calls for payroll taxes also to apply to earned income above $400,000. That would leave earnings between $137,700 and $400,000 free from payroll tax—for now. As the $137,700 threshold is increased each year with inflation, eventually all earned income would be subject to payroll taxes.

In 2017, the federal estate tax exemption was doubled, which means those who die in 2020 can leave $11.58 million free of federal estate taxes. In 2026, the exemption is scheduled to return to $5.5 million. Will it happen? Today, if you hold assets in a taxable account with unrealized capital gains, that potential tax bill disappears when you die, thanks to the so-called step-up in cost basis. There’s talk of eliminating the step-up in cost basis—and this could be part of a tradeoff to maintain today’s higher estate tax exemption.

Most 401(k) contributions come from higher-income earners, who are able to take a tax deduction for the money they save. Many low-income families either don’t fund 401(k) plans or don’t earn enough to benefit much from the deduction. To help these families, some have proposed giving folks a 26% tax credit, instead of a tax deduction, for their 401(k) contributions.

Will all these changes happen? Much depends on whether a single party ends up controlling both the White House and Capitol Hill. From what I’ve read, we’re most likely to see an increase in the capital gains rate for high-income earners, an elimination of the step-up upon death and a change to the 401(k) deduction. Got large unrealized capital gains? You may need to rethink your estate plan, just as retirement account owners needed to rethink their estate plan following this year’s nixing of the stretch IRA.

James McGlynn, CFA, RICP, is chief executive of Next Quarter Century LLC in Fort Worth, Texas, a firm focused on helping clients make smarter decisions about long-term-care insurance, Social Security and other retirement planning issues. He was a mutual fund manager for 30 years. James is the author of Retirement Planning Tips for Baby Boomers. His previous articles include Back When, Fatten That Policy and My Retirement.

James McGlynn, CFA, RICP, is chief executive of Next Quarter Century LLC in Fort Worth, Texas, a firm focused on helping clients make smarter decisions about long-term-care insurance, Social Security and other retirement planning issues. He was a mutual fund manager for 30 years. James is the author of Retirement Planning Tips for Baby Boomers. His previous articles include Back When, Fatten That Policy and My Retirement.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation. Want to receive daily email alerts about new articles? Click here. How about getting our weekly newsletter? Sign up now.

The post The Taxman Cometh appeared first on HumbleDollar.

October 22, 2020

Easy Street

A FEW YEARS AGO, my future husband and I took a trip to southern Utah to participate in a pistol shooting competition. We were taken by the area’s beauty and easy access to outdoor recreational activities. While there, we looked at a few homes and were pleasantly surprised to find the prices quite reasonable. We decided Utah would be high on our list of places to relocate to once I retired from my job.

Soon after we returned home, St. George, Utah, was ranked as one of the fastest-growing metro areas in the country. As the population increased, so too did housing prices. Not long after our visit, we realized we were priced out of the market.

Last year, we learned about a retirement community located just outside of Phoenix. Arizona was another state we were interested in retiring to, so we took a trip to investigate the area. Within a couple of days, we felt we’d found the right location for us and we began house hunting.

It took two months before we closed on a home. We were outbid on two properties before finding a home we felt was ideal for us. We’d formulated a list of criteria for our retirement destination and the house checked every box.

First, we wanted easy access to the various activities we enjoy participating in. Our retirement home is just 20 miles from a world-class shooting range. There are also multiple dog-training clubs throughout the region, which will help us keep our pack of four canines active and engaged.

Live concerts, movies in the park and an overwhelming number of continuing education opportunities are available within the community itself. There are also multiple fitness facilities, a library and several clubs we look forward to joining.

Next on our list was access to health care. With a full-service hospital and multiple physicians’ offices located less than two miles from our home, this box was easily checked.

Having lived in the Pacific Northwest for most of our lives, both my husband and I were interested in retiring to a location with less rain and lower taxes. Arizona met both criteria. Weatherwise, we’ll be trading wet, cold winters for hot, dry summers. Taxwise, we’ll be trading high payments for much lower ones. The property taxes on our 2,000-square-foot Arizona home, located on a 10,000-square-foot lot, are 75% less than the taxes on our 1,100-square-foot home on a city lot in Oregon.

Finally, we knew we wanted to find a home and community that were disability friendly. Although my husband and I are both healthy and active now, we realize this might not always be the case. When my husband underwent knee-replacement surgery last year, it gave us insight into how difficult it can be to negotiate a house that isn’t designed for mobility devices.

Nearly all of the 17,000 houses in our retirement community were built with accessibility in mind. Most are single-story homes with open floor plans and bathrooms designed for use with wheelchairs and walkers. The sidewalks are wide and barrier-free. The major thoroughfares running through the community accommodate three lanes of traffic. Golf carts are street legal.

The entire community was built with the idea of making it easy for residents to age in place. If, in the future, my husband and I need assisted care, there are multiple in-home health care providers available. Residents who need assistance paying for prescription medications, utility bills or appliance repairs can request funds through a community-based, nonprofit charity. Over the past four years, the organization has paid out more than $400,000 in financial assistance to community residents.

I initially questioned our decision to buy a second home before I’d retired. But my husband reminded me of our trip to Utah and now I’m glad I listened to him. Housing prices within the Arizona community have already increased 10% since we purchased our home last year.

Kristine Hayes is a departmental manager at a small, liberal arts college. Her previous articles include Decisions, Decisions, Day by Day and Did It Myself

. Kristine enjoys competitive pistol shooting and hanging out with her husband and their dogs.

Kristine Hayes is a departmental manager at a small, liberal arts college. Her previous articles include Decisions, Decisions, Day by Day and Did It Myself

. Kristine enjoys competitive pistol shooting and hanging out with her husband and their dogs.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation. Want to receive daily email alerts about new articles? Click here. How about getting our weekly newsletter? Sign up now.

The post Easy Street appeared first on HumbleDollar.

October 21, 2020

State of Taxation

ONE OF MY FAVORITE things to do is sit on our local beach with a cold beverage on a beautiful day, and talk finance with interested friends and family members. This past Labor Day weekend, I did just that with a soon-to-be retiree.

One of the big issues facing him and his wife: where to live. He had been relocated to New York by his employer. But he and his wife are natives of the Philadelphia region, and they want to return to the area to be closer to friends and family.

As often happens when retirees and near-retirees talk, the subject of taxes in retirement came up. They’re considering Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Delaware for their retirement years. My wife and I are wrestling with the same issue.

Fortunately, there’s extensive information on the internet. Thirty-seven states and the District of Columbia don’t tax Social Security. But many of these states tax other forms of retirement income. Kiplinger has a good site that provides a detailed state-by-state explanation of the taxes that retirees face, grading each state on its tax-friendliness.

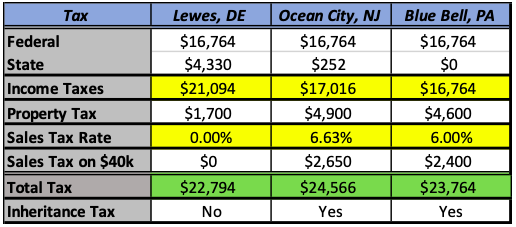

I analyzed locations in the three states that my friends are considering. Specifically, I looked at: Lewes, Delaware; Ocean City, New Jersey; and Blue Bell, Pennsylvania. I assumed annual income of $145,000, comprised of a $60,000 pension, $45,000 in Social Security and $40,000 of retirement account withdrawals. I also assumed a married couple filing a joint return. Here’s what I found:

1. Real estate. I compared the property taxes for a $500,000 home in the three locations. I used real estate listings and public records to compare similar-sized homes. Delaware was the clear winner at $1,700. Ocean City and Blue Bell were almost the same at $4,900 and $4,600, respectively.

2. Social Security. None of the three states tax Social Security.

3. Pension and retirement income. Delaware taxes income from pensions and retirement accounts, but provides a deduction of $12,500 for those age 60 and older. The deduction is $2,000 if you’re under 60. Tax rates can be as high as 6.6%. This highest rate kicks in on taxable income above $60,000.

New Jersey is a little complicated. The state taxes income from pensions and retirement account withdrawals, but provides a special pension exclusion for those 62 and older who fall below a certain income threshold. In 2020, filers meeting the age requirement, and who have total annual income of $100,000 or less, can exclude retirement income of up to $75,000 (single filers) or $100,000 (joint filers). Above $100,000, the exclusion disappears entirely. Tax rates range from 1.4% to 10.75%.

Meanwhile, Pennsylvania doesn’t tax either pensions or withdrawals from IRAs and 401(k)s.

4. Sales tax. Delaware is famous for having no sales tax. Many nearby non-residents take advantage by making large purchases there. Pennsylvania’s statewide rate is 6%, but there are exemptions for products such as clothing, groceries, prescription drugs and residential fuels.

The New Jersey statewide rate is 6.625%. Again, there are exemptions for items that are especially important to seniors. Medicine (prescription and non-prescription), groceries and many types of clothing are exempt from New Jersey’s sales tax.

5. Capital gains. Delaware, New Jersey and Pennsylvania tax short- and long-term capital gains as regular income.

6. Estates. Delaware repealed its estate tax in 2018. New Jersey has an inheritance tax. Bequests to non-relatives, siblings and distant relatives are taxed at rates ranging from 11% to 16%, with the first $25,000 exempt.

Pennsylvania also has an inheritance tax. The inheritance tax rate varies depending on the relationship of the inheritor to the decedent. The tax is 0% for spouses, 4.5% for direct descendants like children and grandchildren, 12% for siblings and 15% for everybody else.

The table below summarizes the scenario I evaluated. Delaware is a modest winner once sales taxes are factored in. If we assume that $40,000 of the $145,000 income is spent on taxable items, it adds another $2,600 or so to the New Jersey and Pennsylvania tax bill. The upshot: A retiree who lives in Ocean City, New Jersey, would pay about $2,000 more in taxes than a similar retiree in Lewes, Delaware. That’s not necessarily a game changer, but certainly something to consider.

One important factor not captured in this analysis: the cost of housing. I used $500,000 as the assessed value, but that can buy very different homes in the three locations. Also, depending on the age of the house, the assessed value for tax purposes could be much lower than the market value.

A final caveat: It’s critical to understand the New Jersey hard limit of $100,000 in total income to get the retirement income exclusion. An additional $1,000 of income raises the New Jersey state tax from $252 to $2,746.

Richard Connor is a semi-retired aerospace engineer with a keen interest in finance. Rick enjoys a wide variety of other interests, including chasing grandkids, space, sports, travel, winemaking and reading. His previous articles include Paradise Lost, Much Appreciated and Victims of the Virus. Follow Rick on Twitter @RConnor609.

Richard Connor is a semi-retired aerospace engineer with a keen interest in finance. Rick enjoys a wide variety of other interests, including chasing grandkids, space, sports, travel, winemaking and reading. His previous articles include Paradise Lost, Much Appreciated and Victims of the Virus. Follow Rick on Twitter @RConnor609.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation. Want to receive daily email alerts about new articles? Click here. How about getting our weekly newsletter? Sign up now.

The post State of Taxation appeared first on HumbleDollar.

October 20, 2020

Make the Connection

FOR A LIFE to be meaningful, it doesn’t need to be unique—and yet many of us believe that’s necessary. We’re convinced we lack something special, and that paralyzes us. This is a mistake, says the philosopher Iddo Landau, who argues that everybody already possesses what they need for a meaningful existence. We just need to look harder.

I’ve spent years researching and educating myself on how to find and cultivate purpose. This helped me to develop a process to guide clients, as they seek to construct a fulfilling post-career life. A large pile of dollars isn’t enough. Instead, to create a more meaningful life, we need to spend more time thinking about ourselves and the world around us. Through this, I learned one way we can discover our purpose and add meaning to our life: turn suffering into healing.

That brings me to our 13-year-old dog Samantha, a redbone coonhound. She was approaching the end of her life. What we didn’t know was if or when to intervene. We had several discussions with our vet, Dr. Rick White, seeking his counsel. After an exceptionally rough week for Samantha, we knew it was time.

Shortly after arriving at his office, White greeted us. The exam room was different than what we were used to. The lights were low, there was a comfortable bed on the floor for Samantha and a couch for us. White immediately sat on the floor, at Samantha’s level, and lovingly talked to her, like you would to an old friend. He walked us through the entire process, assuring us that Samantha would experience no pain and, in fact, would feel peace.

His demeanor was compassionate and calming, and his words wise. He listened with keen interest as we recounted our favorite things about Samantha and, when appropriate, interjected his own stories. Mostly, he made us feel as if we were the only people at the vet practice and, like us, Samantha was also his own.

When the tears streamed down our faces, he encouraged our emotions. He noted our humanity and our deep love, remarking, “It’s the ones that don’t get choked up, or show emotion, that I worry about.” He was comfortable with and comforted by our tears. Throughout the procedure, he knew what to say, when to say it and how to say it.

Perhaps the greatest gift he gave us was perspective. He reminded us that most people in this world do not pass away surrounded by their loved ones and the people they trust the most. We should all be so lucky when our time comes.

Meaning and purpose arise not just from intrinsic traits, but also from our connection to others. Using our time and money to cultivate those connections is one of the best possible investments, helping to make today more fulfilling and the end of our life more peaceful. When we thanked White for his excellent care over the years, he responded, “There is nothing else I’d rather do.”

Anika Hedstrom, MBA, CFP, is a personal finance expert and advisor. Her previous articles include Effort Counts Twice, Stay in Your Lane and Known and Unknown. Anika writes on motivational and behavioral aspects of financial planning, and has been featured in USA Today, MarketWatch, Huffington Post, Business Insider and NPR. Always up for adventure, Anika can be found exploring new countries, whitewater rafting and chasing after her twins. Follow her on Twitter

@AnikaHedstrom

.

Anika Hedstrom, MBA, CFP, is a personal finance expert and advisor. Her previous articles include Effort Counts Twice, Stay in Your Lane and Known and Unknown. Anika writes on motivational and behavioral aspects of financial planning, and has been featured in USA Today, MarketWatch, Huffington Post, Business Insider and NPR. Always up for adventure, Anika can be found exploring new countries, whitewater rafting and chasing after her twins. Follow her on Twitter

@AnikaHedstrom

.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation. Want to receive daily email alerts about new articles? Click here. How about getting our weekly newsletter? Sign up now.

The post Make the Connection appeared first on HumbleDollar.

October 19, 2020

Shooting Stars

THEY WERE GURUS and gunslingers. Market mavens. Stock pickers and sector bettors. Over in the bond market, there was even a king. They were star fund managers—but most were shooting stars, destined to crash.

Yes, we’ve had managers like Peter Lynch, Will Danoff and Bill Gross, whose long-term returns did indeed beat the indexes. But for every winner like them, there have been—statistically speaking—seven who failed. Between 74% and 93% of funds in a variety of broad categories—small-cap, large-cap, growth, value and so on—lagged behind their relevant benchmark over the past 15 years, according to the latest research by S&P Dow Jones Indices.

On top of that, there’s no way to predict whether a manager’s run of outperformance will continue. Just because a manager shines in any given period doesn’t mean he or she will remain top quintile.

Lynch, former manager of Fidelity Magellan Fund, and Gross, former manager of PIMCO Total Return bond fund, ended their careers with great 10-year-plus records. Danoff, who has been at the helm of Fidelity Contrafund for 30 years, still outperforms the S&P 500 index—though he trails the Russell 1000 growth index, which is arguably more relevant. How much is skill and how much is luck? Index fund progenitor Jack Bogle, founder of Vanguard Group, praised Lynch—along with former Vanguard Windsor manager John Neff—as among the few consistent market-beaters who have demonstrated skill.

I’m not discounting their achievements, but the fact that a few investors—maybe including your annoying neighbor—beat the averages over the long term is just a statistical necessity. Someone or something has to be top decile in any data set. Flip a group of quarters repeatedly: One or two of them are going to come up heads a whole lot more than the others. Almost as inevitably, above-average readings are likely to be followed by a losing streak, possibly wiping out the winning margin. It’s called reversion to the mean.

Among the fund stars whose outperformance didn’t last: Bill Miller, Ken Heebner, Mark Mobius, Bill Berger, Wally Weitz, Garrett Van Wagoner and Donald Yacktman. My point isn’t to cast aspersions on these managers. Many others fell by the wayside—and some funds never shone at all.

Celebrated managers justified their high fees for retail investors with the promise that they were proven market beaters. But they had plenty of help in their self-promotion. From about 1990 through the 2000s, star managers shared a symbiotic existence with the financial press.

To publicize their track record and attract more money from investors, such managers needed the limelight, their names in big letters, their faces on the cover of personal finance magazines and their prime airtime on Squawk Box. When they gathered more investor dollars than they could handle, their PR people sometimes stopped making them available for interviews. Other times, they just kept raking it in until the funds were too bloated to follow their original investment strategy.

Meanwhile, the finance magazines needed to sell copies and the cable networks needed to keep eyeballs glued to them, with the tantalizing but dangerously flawed prospect that readers and viewers could profit from star managers’ favorite stocks and strategies, and even from their economic and political prognostications.

I recall what a highly regarded but somewhat media-shy small-cap manager at T. Rowe Price told me 20 years ago: When talking to the press about the stocks he likes, he needed to avoid touting those he was actively buying. So what a magazine might have called his “top stocks to buy now” were not exactly that, though they certainly could have been good investment recommendations. This reality didn’t stop the press and the more attention-seeking portfolio managers from playing the game.

The triumph of index mutual funds and exchange-traded index funds, along with the internet’s devastation of the print media, have changed the game. Money magazine is now exclusively online. It used to be a fat, glossy publication filled with ads for mutual funds that did nothing more than beat their category averages. It’s now a virtual shell of itself. The devastating bear markets of 2000-02 and 2007-09 also seem to have soured retail investors on the star manager parlor game.

That was the game I played when I was cutting my investment teeth. I pored over many a mutual fund table, subscribed to many a magazine, invested in many funds and often changed my mind, buying high and selling low. Today, I’ve learned my lesson—and many other investors are older and wiser, too.

A game is always afoot, however, as Sherlock Holmes would say. What are we playing today? Cryptocurrencies? Robinhood? Smart-beta ETFs? The handful of mega-cap tech stocks that are the only things holding up the S&P 500 this year? All we know for sure is that years from now we will look back, give a rueful laugh and shake our heads at the money we might have made—or, in most cases, saved.

William Ehart is a journalist in the Washington, D.C., area.

Bill’s previous articles include Different Strokes, Needing to Know and

Played for Fools

. In his spare time, he enjoys writing for beginning and intermediate investors on why they should invest and how simple it can be, despite all the financial noise. Follow Bill on Twitter

@BillEhart

.

William Ehart is a journalist in the Washington, D.C., area.

Bill’s previous articles include Different Strokes, Needing to Know and

Played for Fools

. In his spare time, he enjoys writing for beginning and intermediate investors on why they should invest and how simple it can be, despite all the financial noise. Follow Bill on Twitter

@BillEhart

.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation. Want to receive daily email alerts about new articles? Click here. How about getting our weekly newsletter? Sign up now.

The post Shooting Stars appeared first on HumbleDollar.

October 18, 2020

Follow the Fed

STOCKS WENT INTO a freefall earlier this year, as I’m sure you recall. But all of a sudden, on March 23, everything changed. The market turned around and, just as quickly as it had dropped, it rebounded. Remarkably, the U.S. stock market is now in positive territory for the year.

What happened on March 23? The situation with the virus didn’t get any better. And it wasn’t Congress or the White House. What happened was that the Federal Reserve issued a statement. In that statement, it announced that it would use its “full range of tools” to help rescue the economy. And, just like that, both the stock and bond markets turned positive and haven’t looked back since.

But for all the Fed’s power, it’s a somewhat inscrutable entity and not well understood. Perhaps that’s why, at the end of August, when the Fed announced revisions to a document some refer to as the Fed’s “constitution,” it didn’t receive nearly as much attention as it deserved.

That document is called the “Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy.” While that might sound arcane, it’s an important document to understand because of the Fed’s enormous power to move markets.

By way of background, the Fed first created this policy document in 2012 in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. It describes in straightforward terms how the Fed sees its mandate. Since 2012, the Fed—despite changes in leadership—has reaffirmed this same document each year. But this summer, as the economy grappled with the impact of the coronavirus, Fed officials realized that it was due for an update. These were the key changes:

Employment. The Fed’s dual mandate has always included both controlling inflation and maintaining full employment—and it has always stated them in that order. But in the updated document, the Fed says it will now make full employment its first priority.

Inflation. In the past, the Fed’s goal has been to achieve an inflation rate of 2%—not higher and not lower. But the updated policy document paints a different picture. The Fed will now target “inflation that averages 2 percent over time.” The key word here is “averages.” The Fed will now allow, and at times even encourage, inflation that runs above 2% to make up for periods during which it’s run below that level.

While these may sound like subtle changes, there are seven key implications for individual investors:

1. Expect low yields. In the Fed’s new framework, it won’t be in a hurry to raise rates even after the economy gets back to normal, which will hopefully be in the next year or two. That’s because, even after a recovery, policymakers will allow time for inflation to reach 2% on average over time. And since we’re currently so far below 2%, it may be another few years or more before that multi-year average is achieved.

In fact, in another document issued last month, the Fed said as much. A survey of Fed officials indicated that they expect short-term interest rates to remain anchored near zero through 2023. The implication: If you’re trying to estimate the returns your portfolio might deliver, it would be prudent to assume a continuation of today’s super-low rates and not bet on anything higher.

2. Plan for higher inflation. It will now be even more important to consider a variety of inflation scenarios in your financial plan. Do you need to worry about inflation topping 10%, like we saw in the 1970s? Probably not. But if the Fed’s target is 2% on average, and we’re currently at 1.4%, you should certainly consider the impact on your financial plan of rates in the 2% to 3% range. While this may not sound like much of a difference, a single percentage point can definitely make a difference when compounded over time.

3. Rethink asset location. In the past, an investment rule of thumb was to hold bonds in retirement accounts, where interest payments would be shielded from taxes. But with rates so low today—and maybe for a while—that’s less important. Even if you’re in a high tax bracket, you should now feel free to hold taxable bonds in taxable accounts if that better suits your needs.

4. Favor the middle. Today, there aren’t meaningful differences among the yields on short-, intermediate- and long-term bonds. But under the Fed’s new framework, it’s possible that more of a gap might open up as the economy improves. That’s because the Fed controls short-term rates and it’s said it’ll be keeping these rates near zero for a good long while. Meanwhile, if investors see the economy improving, they may bid up rates on intermediate- and long-term bonds.

Result? While I’m not ready to recommend long-term bonds, I do think there’s value in holding intermediate-term bonds. Yes, rising rates translate into falling prices initially. But there’s a silver lining: Over time, those rising rates translate into higher bond returns.

5. Protect against inflation. Because higher inflation is now more likely, I think it’s even more important to build inflation protection into portfolios. The most effective means to accomplish that, in my opinion, is with inflation-indexed Treasury bonds, formally known as Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities, or TIPS.

6. Stay flexible. When it comes to investment strategy, I’m a big believer in consistency. Those who change strategies too frequently risk whipsaw. But this change in the Fed’s “constitution” serves as a reminder that things can and do change—sometimes in meaningful ways. As you formulate your investment strategy, try to balance consistency with flexibility.

To be sure, historical patterns are important for reference, but there’s no guarantee that the future will mirror the past. In fact, the Fed said as much in the final sentence of its new document. Instead of saying that it would reaffirm the document each year, the new language merely commits to reviewing it. The bottom line: This new policy is itself subject to change.

7. Avoid gold. Despite the potential for higher inflation, I still don’t recommend buying gold as an investment. While gold enjoys a reputation as a hedge against inflation, it hasn’t reliably delivered on that promise. As the historical data show, it’s been more of a hedge against economic uncertainty. But if you want true inflation protection, gold is just a gamble.

Adam M. Grossman’s previous articles include Save and Give First, Don’t Play Politics and High Anxiety

. Adam is the founder of

Mayport

, a fixed-fee wealth management firm. In his series of free

e-books

, Adam advocates an evidence-based approach to personal finance. Follow Adam on Twitter

@AdamMGrossman

.

Adam M. Grossman’s previous articles include Save and Give First, Don’t Play Politics and High Anxiety

. Adam is the founder of

Mayport

, a fixed-fee wealth management firm. In his series of free

e-books

, Adam advocates an evidence-based approach to personal finance. Follow Adam on Twitter

@AdamMGrossman

.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation. Want to receive daily email alerts about new articles? Click here. How about getting our weekly newsletter? Sign up now.

The post Follow the Fed appeared first on HumbleDollar.

October 17, 2020

Where We Stand

THIS YEAR’S PANDEMIC has unleashed financial turmoil for many American families, so data from last year might seem irrelevant. Still, there’s one set of 2019 data that deserves our attention—the Federal Reserve’s latest Survey of Consumer Finances, which was released last month.

Conducted every three years, the survey is perhaps the most in-depth look we get at the state of America’s personal finances. For the 2019 survey, 5,783 families (who may be individuals living alone) were interviewed at length about their income, assets and debts, resulting in fascinating insights into how we handle money:

As of 2019, 52.6% of families were invested in the stock market, up from 51.9% three years earlier, but below the 53.2% peak recorded in 2007. The survey’s data show we became a nation of stock market investors during the great 1990s bull market, with the percentage of families invested in the market rising from 31.9% in 1989 to 53% in 2001. We’ve remained at around that level ever since, despite the brutal bear markets of 2000-02 and 2007-09. Wall Street “professionals” love to heap scorn on everyday investors, and yet it seems American families have defied their churlish critics and prudently stayed the course.

The typical family’s net worth—meaning their assets minus their debts—was $122,000 as of 2019. This $122,000 is what mathematicians call a “median,” meaning it’s the number you get if you array the survey’s findings from highest to lowest and then pick the net worth that’s halfway down the list.

By contrast, the average net worth was $747,000. This average is what mathematicians call a “mean.” You find it by adding up the net worth of the families surveyed and then dividing this sum by the total number of families. Why is the mean so much higher than the median? The mean is skewed higher by a relatively small number of families with great wealth.

There’s been much talk about growing inequality. One indication: The median net worth of American families has climbed an inflation-adjusted 30% over the past 30 years, while the mean has jumped 98%. But over the past three years, mean net worth has grown far slower than median net worth—and mean income actually fell while median income rose—suggesting that wealth and income inequality are lessening.

Last year, 64.9% of families reported owning their primary residence, up from 63.7% three years earlier but below 2004’s peak of 69%. That peak was during the housing bubble—and it seems to have been an aberration. Homeownership today is about where it stood 30 years ago. The median value of Americans’ primary residence was $225,000 in 2019, up from $139,000 in 1989. Both figures are calculated in 2019 dollars, and thus the increase isn’t simply a reflection of general price inflation.

Among homeowners, 64.8% have a mortgage or other debt that’s secured by their home. Those with home-secured debt owe a median $135,000. Meanwhile, 76.6% of American families have some sort of debt. That includes 45.4% of families who were carrying a credit card balance, up from 38.1% six years earlier. Among those with a balance, the median amount is $2,700, while the mean is $6,270. As with net worth, the mean credit card balance is skewed higher by those with hefty amounts of card debt.

But perhaps the most notable trend is soaring education debt, which is now a burden for 21.4% of families, up from 8.9% three decades ago. Among those under age 35, 41.4% report having education debt, with a median amount owed of $22,000.

The Fed’s survey offers a glimpse of America’s retirement readiness. Among households headed by someone age 65 to 74, the median net worth was $266,000. This doesn’t count the value of Social Security benefits or defined benefit pension plans. For this group, homeownership stood at 78.4%, but just 48.2% said they had an IRA or a similar retirement account. Despite the common advice to retire debt-free, 70% of these folks were carrying some form of debt, including 37.6% who had debt secured by their home. The median amount of home-secured debt was $89,000.

Ownership of cars and other vehicles has remained fairly steady over the decades, with 85.4% of families owning a vehicle as of 2019. The median value of these vehicles, however, has climbed sharply, from $12,000 in 1992 to $17,000 last year. Both figures are in 2019 dollars.

How about a certificate of deposit, a savings bond or cash-value life insurance? It seems more Americans are saying “no” to all three. These products have seen a sharp drop in ownership over the past 30 years.

Latest Articles

HERE ARE THE SIX other articles published by HumbleDollar this week:

“After 100 days on the multiple listing service, the missus informed me I could get out of the fetal position,” recounts Mike Flack. “We had just received not one offer, but two.”

Want to turn yourself into a more tenacious investor? Check out the seven tips from Dennis Friedman.

“I’m told earnings drive share prices,” writes Richard Quinn. “But if I don’t get paid my share of those higher earnings as dividends, why pay more for the stock? Somebody is gambling, I think.”

How do you find the right financial advisor? John Yeigh got that question from his family. Here’s what he told them.

“If you’ve already set aside the amounts you’ll need for savings and for giving, you can—in theory—freely spend the remainder,” says Adam Grossman. “Many people find this liberating.”

Swashbuckling money managers may flaunt their confidence about the likely direction of stocks and bonds—but many of the most celebrated investment experts are far more humble, notes Robin Powell.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter @ClementsMoney and on Facebook. His most recent articles include Game Over, Pay It Forward and Not Exactly True.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter @ClementsMoney and on Facebook. His most recent articles include Game Over, Pay It Forward and Not Exactly True.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation. Want to receive daily email alerts about new articles? Click here. How about getting our weekly newsletter? Sign up now.

The post Where We Stand appeared first on HumbleDollar.

October 16, 2020

No Need to Guess

IT SEEMS EVERYONE has an opinion about the markets—and they are, of course, entitled to those opinions. But here’s the irony: Some of the most successful investors have also been among the least dogmatic in expressing their views.

Perhaps it’s the humility gained from repeatedly trying and failing to second-guess the financial markets. These veteran observers of markets are a stark contrast to the swashbuckling managers who flaunt their confidence about the likely direction of stocks and bonds—a sales strategy they use to encourage people to buy products they don’t need.

If what people need is the promise of certainty, the latter group will almost certainly attempt to sell it to them. Meanwhile, the former group—the truth-telling veterans—will advise that, as in life more generally, there’s no certainty in markets. Instead, there are only ways of mitigating risk.

The great American financial historian Peter Bernstein was one of the truth-tellers, warning people that—even with the most powerful computers—no investment model could ever perfectly factor in every risk or the possibility that the previously unthinkable might become reality. “The essence of risk management lies in maximizing the areas where we have some control over the outcome while minimizing the areas where we have absolutely no control…. and (where) the linkage between effect and cause is hidden from us,” he wrote.

Warren Buffett is another of the truth-tellers. Constantly asked for his economic and market outlook, the Sage of Omaha takes a deep breath and says speculation is pointless. “I don’t think anybody knows what the market is going to do tomorrow, next week, next month or next year,” Buffett told Berkshire Hathaway’s annual meeting in 2020, during the pandemic. “I know America is going to move forward over time, but I don’t know for sure.”

Addressing the question of risk on another occasion, Buffett said the flipside of uncertainty was the opportunity this presented to the long-term, disciplined investor: “An argument is made that there are just too many question marks about the near future. ‘Wouldn’t it be better to wait until things clear up a bit?’ Before reaching for that crutch, face up to two unpleasant facts: The future is never clear and you pay a very high price for a cheery consensus. Uncertainty actually is the friend of the buyer of long-term values.”

Another champion of investment humility is the renowned consultant Charley Ellis, who founded Greenwich Associates in the early 1970s. Ellis’s view, expressed in his book Winning the Loser’s Game, is the futility of seeking to outguess the market.

“The best way to achieve long-term success is not in stock picking and not in market timing and not even in changing portfolio strategy,” Ellis said. “Sure, these approaches all have their current heroes and war stories, but few hero investors last for long and not all the war stories are entirely true. The great pathway to long-term success comes via sound, sustained investment policy, setting the right asset mix and holding onto it.”

None of this is particularly sexy. It doesn’t involve the promise of overnight success and it doesn’t conjure up images of heroic figures pitting their wits against the world. It involves old-fashioned virtues such as humility, patience, discipline and keeping a level head.

On the positive side, it also means that you don’t have to take falling markets personally, just as you shouldn’t claim rising markets as vindication of your investment smarts. Much as the media might suggest otherwise, investing is not a competition.

For individual investors, a good plan is one they can live with and that allocates their assets to maximize their chances of reaching their goals in their desired timeframe. Risk is managed through diversification, while attention is paid to costs and taxes. The portfolio should be periodically rebalanced as markets change and as needs and circumstances evolve.

No plan will be perfect. It can never encompass every risk. Outlier events can always occur. But risk can be managed, at least up to a point, and there are strategies to help us deal with events that no one saw coming, such as a financial crisis, a geopolitical event or a pandemic.

These simple truths were expressed most eloquently and concisely by the great Jack Bogle, the founder of Vanguard Group and one of the pioneers of index funds. “The greatest enemy of a good plan is the dream of a perfect plan,” Bogle wrote. “Stick to the good plan.”

Amen to that.

Robin Powell is an award-winning journalist. He’s a campaigner for positive change in global investing, advocating for better investor education and greater transparency. Robin is the editor of The Evidence-Based Investor, which is where a version of this article first appeared. Regis Media owns the copyright to the above article, which can’t be republished without permission. Robin’s previous articles include What’s the Plan, The Good Advisor and Death by Lifestyle. Follow Robin on Twitter @RobinJPowell.

Robin Powell is an award-winning journalist. He’s a campaigner for positive change in global investing, advocating for better investor education and greater transparency. Robin is the editor of The Evidence-Based Investor, which is where a version of this article first appeared. Regis Media owns the copyright to the above article, which can’t be republished without permission. Robin’s previous articles include What’s the Plan, The Good Advisor and Death by Lifestyle. Follow Robin on Twitter @RobinJPowell.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation. Want to receive daily email alerts about new articles? Click here. How about getting our weekly newsletter? Sign up now.

The post No Need to Guess appeared first on HumbleDollar.

October 15, 2020

Helping Out

SOME FAMILY members recently asked me to help them find a financial advisor. As luck would have it, soon after, Barron’s published a perfectly timed article, “America’s Best RIA Firms,” which listed 100 highly ranked registered investment advisors (RIAs). Similar lists are available from CNBC and the Financial Times.

It was time for me to get to work. Who wouldn’t want to recommend a “top” firm to his or her family?

The Barron’s article provided four pieces of information for each firm: the number of clients, advisors and offices, as well as the number of states where those offices are located. This allowed me to calculate the client-to-advisor ratio, which ranged from five to 3,855 clients per advisor. My family neither required nor could afford the attention of 20% of an advisor’s time, but they also needed more support than an advisor who was handling thousands of clients.

Some web research indicated that the typical number of clients per advisor is around 150. As few as 50 higher net worth clients is often sufficient for an advisor to generate a decent income. Assuming 2,000 working hours per year, an advisor with 150 clients can devote about one hour per month to each client, but that would include time handling paperwork, developing financial plans, following markets, and keeping up with tax and regulatory changes.

In other words, the advisor might be able to chat with a client for 30 or 40 minutes per month. (In practice, advisors typically talk to clients less frequently, but for longer.) Several articles suggested that, if an advisor wants to maintain a good relationship with his or her clients, the maximum number of clients should be even less—perhaps just 100. That means an important first question to ask any potential new advisor is, how many clients are you currently serving?

This leads to a related question: What’s your average client account balance? I came across several RIAs that had clients with average account balances in excess of $30 million. One RIA required $20 million to open an account. Relatively few RIAs manage average account balances in the low hundreds of thousands. Clearly, many of these firms were working with folks who are in a different league from my family.

My family also wanted to understand the costs involved. From scouring the web, it seems RIA fees range from 2.5% of an account’s value each year to 0.75%, though that lower fee was often only available for larger accounts. That said, many firms don’t openly advertise their fees and nearly all the fine print indicates that the fees are “negotiable.”

Whether a fee is reasonable depends on the services involved. An advisory firm could provide portfolio management only or it could offer full-on financial, retirement, insurance, portfolio, tax and estate planning. It’s also important to find out whether the firm is fee-only or whether it also collects commissions, and whether it operates as a fiduciary, meaning it’s legally obligated to act in the best interest of clients. I found that a financial advisor providing the sort of guidance my family was seeking would likely cost about 1% of their account value each year.

A quick analysis suggested the Barron’s RIAs were not ideal for my family’s situation because the required minimums were too high. Time for Plan B. A number of websites match clients and advisors based on an array of inputs. These include NAPFA.org, PlannerSearch.org and SmartAsset.com. I forwarded these links to my family. Robo-advisors were also an option, but my family needed more support than robos typically offer.

In addition, I encouraged my family to check out the major low-cost brokerage and fund firms. Vanguard Group, Fidelity Investments and Charles Schwab, among others, offer relatively inexpensive advisory services. Vanguard’s fee is just 0.3% a year, with a minimum account size of $50,000. Fidelity’s fee is 0.5%, with an even more modest minimum of $25,000. Likewise, Schwab has a $25,000 minimum, but is significantly more expensive for smaller accounts. Like almost all advisors, these major financial firms will provide a free initial free consultation. They also offer lower-cost—and sometimes free—online alternatives.

My family still hasn’t decided which route to go. But if they opt for an individual investment advisor, rather than one of the large financial firms, I’ve suggested they ensure the advisor has a conservative, low-cost investment philosophy, which would be a good match for their limited investment experience. I’ve also recommended they check out potential advisors through FINRA, the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority. There may be additional information on the Securities and Exchange Commission’s website.

John Yeigh is an engineer with an MBA in finance. He retired in 2017 after 40 years in the oil industry, where he helped negotiate financial details for multi-billion-dollar international projects. His previous articles include While We’re Waiting, Bankrolling Roth and Losing My Balance.

John Yeigh is an engineer with an MBA in finance. He retired in 2017 after 40 years in the oil industry, where he helped negotiate financial details for multi-billion-dollar international projects. His previous articles include While We’re Waiting, Bankrolling Roth and Losing My Balance.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation. Want to receive daily email alerts about new articles? Click here. How about getting our weekly newsletter? Sign up now.

The post Helping Out appeared first on HumbleDollar.