Jonathan Clements's Blog, page 312

September 24, 2020

Leaving Early

LIKE OTHERS, I took my first part-time job as a teenager and, once working fulltime, stayed at it steadily for decades. Being an adult meant being a worker, affiliated with some firm or another, one industry or another.

My plans for ever exiting the labor force were vague: “Save for the future, so someday you will retire with honor and dignity to spend your waning days as you desire.” I saved steadily, putting me on track for future retirement. The past 15 years at work have been rewarding, challenging, and required every bit of skill and effort I could muster, and I loved my work. As friends and family retired before me, I began wondering if I’d be one of those people who never stop.

But that changed in 2019. I spent most of the year dealing with my husband’s death and a spell of accident-induced temporary disability, before returning to campus last fall. But even before the first day of class, I notified my dean that I was considering early retirement at year’s end—assuming a suitable exit package could be structured.

Due to my injury, my commute by car and train was difficult to manage. I was still grieving for my life’s partner and the future we had anticipated, with little clarity about the alternate future I was now creating on my own. Additional responsibilities as a single parent added to my worries.

Whenever we discussed retirement, my husband—who was retired at the time of his death—encouraged me to continue working as long as I felt effective and engaged in my duties. Before he passed away, our plan had been for me to work another five years. By then, our youngest would be out of high school and we could unwind as empty nesters.

But after my husband’s death and my injury, ongoing employment hindered my efforts to rebuild my physical strength and precluded the proximity essential for dealing with the needs of three teenagers. I simply would pay too high a personal cost to work five more years at the university, where—in addition to teaching—I had served as a program director and an associate dean.

I knew my tenured status would protect me, should I decide to soldier on for five or even 15 more years, but I had no interest in being that professor who hangs on way beyond his or her “best by” date. Tenure and years of goodwill had—I hoped—set me up to arrange a financially attractive early exit, one that could mitigate the drawbacks of retiring early.

Negotiating my retirement package took months. But by the end of the semester, we found enough common ground to cut a deal. Reaching an agreement with my employer then freed up mental space to begin contemplating my next big decision: when to claim Social Security. As with retirement generally, Social Security is a topic where mental mistakes often can lead to poor choices.

What did I learn from both my own retirement and that of my late husband? Here are six key lessons.

Neither you nor your partner may work as long as expected. Nearly half of us retire earlier than we anticipate.

To get your best exit package, you need to be prepared to walk away from the negotiation. For me, Plan A was severance. Plan B, I would continue working and ask again the next year. Plan C was simply to separate without severance. I could have coped with any of these three outcomes—and that allowed me to be calm and careful in negotiating my preferred Plan A.

Leaving any position is stressful. It’s helpful to have a sounding board, whether it’s a family member or a professional advisor, such as a lawyer or accountant.

No matter how much your career has meant to you, it’s ultimately a job, not your life. Similarly, negotiating an exit package is a business deal. It isn’t a valuation of your worth as a human being. As others leave your employer, pay attention to what happens. Are voluntary separation packages ever available? What’s typically in them?

Few things make a retiree happier than a spouse who has a fulltime job. That continued employment often comes with health care and other benefits, along with a salary.

Leaving your job at the right moment and on a high note ought to feel good. If the idea of being “retired early” feels bad, let that be the impetus to begin seeking out your next act.

Catherine Horiuchi recently retired from the University of San Francisco’s School of Management, where she was an associate professor teaching graduate courses in public policy, public finance and government technology. Catherine’s earlier articles include Good Company, From Two to One and Missing a Step.

Catherine Horiuchi recently retired from the University of San Francisco’s School of Management, where she was an associate professor teaching graduate courses in public policy, public finance and government technology. Catherine’s earlier articles include Good Company, From Two to One and Missing a Step.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation. Want to receive daily email alerts about new articles? Click here. How about getting our weekly newsletter? Sign up now.

The post Leaving Early appeared first on HumbleDollar.

September 23, 2020

Saved by a Crash

THIS IS THE STORY of a bitter life lesson that taught me two things: the desirability of managing my own investments and the perils of putting almost all my eggs in one basket.

In the late 1980s—and early in our marriage—my wife and I were busy raising four kids, while also managing two demanding careers. Our dream was to build a beautiful house on a large wooded lot that we owned in the hills west of Austin, Texas. We had already hired an architect, who was drawing up the plans, and we expected to pay for the house from our stock portfolio.

When I graduated from law school, I was fortunate to have a few stock market investments, courtesy of my parents, who were firm believers in working hard, saving and investing. This was back before the internet, the explosion of low-cost brokerage firms and the popularity of index funds.

In those days, it was common to use a stockbroker, the old-fashioned kind who charged hefty commissions and did all the trading for you. We lived in a different city from my parents, so I needed to find a stockbroker on my own. I wasn’t sure quite where to begin. I finally decided to call up the only rich guy I knew and ask him who his broker was. The rich guy’s broker was, by all accounts, very reputable. He was a partner in a big brokerage firm, with a fancy office in a skyscraper downtown. To my inexperienced mind, he really knew his stuff.

Between the kids and my career—I was working 60 hard and stressful hours a week—I had neither the time nor the interest to worry about our investments, so I was content to have my new broker take care of them. It soon became clear that he was in love with one particular stock, a health care company called Medical Care America (MCA). Before long, about 90% of our stock portfolio was in that one stock.

Naive and preoccupied as I was, I still should’ve realized this was a problem. But I didn’t. Besides, I had this well-respected stockbroker looking out for me. What could go wrong? Our MCA stock eventually dropped almost 60% in a single day, that’s what.

I can still remember being so upset that I called our venerable broker at home on a Sunday. When I told him that we were counting on the stock to fund our dream home, and what could we do now, he replied, “Build a smaller house.”

A little late, I guess, but the lightbulb went off. I decided there and then that it was up to me to manage our investments and I would never again blindly put my trust in anyone, no matter how well regarded. I began to do my homework and, a few years later, was helped by the coming of the internet and the wealth of financial information it provided. I was also helped by the rapid growth of investment houses with low fees that were built around the idea of assisting independent, do-it-yourself investors.

I abandoned traditional brokerage firms for good and established accounts at Vanguard Group and Charles Schwab, where we’ve happily remained ever since, and where I’ve maintained a low-cost and well-diversified mix of stock and bond investments, mainly index mutual funds and exchange-traded index funds.

The collapse of MCA’s stock was a hard and bitter lesson. But my wife and I were lucky it occurred early enough in our lives for us to recover. In many ways, it was the stock crash that saved us—and turned us into independent investors. While the day may come when I’m too old and senile to manage our investments by myself, the poor soul who gets the job of helping me will have to live with a cranky old man forever looking over his or her shoulder.

Andrew Forsythe retired in 2017 after almost four decades of practicing criminal law, first as a prosecutor and then as a defense attorney. Along with his wonderful wife, kids and grandkids, he loves dogs and collecting pocketknives.

Andrew Forsythe retired in 2017 after almost four decades of practicing criminal law, first as a prosecutor and then as a defense attorney. Along with his wonderful wife, kids and grandkids, he loves dogs and collecting pocketknives.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation. Want to receive daily email alerts about new articles? Click here. How about getting our weekly newsletter? Sign up now.

The post Saved by a Crash appeared first on HumbleDollar.

September 22, 2020

Limited Selection

BY EARLY 2009, I had been investing for 22 years. My wife had invested for a bit longer, and our savings were starting to seem like a significant chunk of money. I was reasonably happy with our investments. Still, I knew that—for those 22 years—we had been paying too much in investment expenses, thanks to the high-fee funds in our employer-sponsored retirement accounts.

Another source of frustration was that our money was spread over seven financial accounts and 14 mutual funds. First, there was my 457 account through the University of North Carolina (UNC), where I did my initial investing. The funds there didn’t perform particularly well, so I was no longer contributing money. Second, there was my 403(b), also through UNC. The best options there—or, at least, what the salesman persuaded me to buy—were several American Funds mutual funds with 5% front-end loads.

Third, my wife had a 403(b) through Nationwide from when she worked for the state as a clinical social worker. She had three actively managed funds in that account. Fourth, in 1998, my wife quit her job with the state to build up her private practice as a clinical social worker. I set up a SIMPLE IRA with Vanguard Group, so she could save part of the money she earned. We also each had Roth IRAs to which we were contributing regularly. Those were accounts Nos. 5 and 6. Finally, because we have no children and we kept our expenses relatively low, and because I’d received several promotions, we had additional money every month to invest, so we put those dollars in a Vanguard taxable account.

All those different accounts made for some complex accounting, but I had them all in a spreadsheet that allowed me to track what percentages we had in U.S. large-cap stocks, mid-caps, small-caps, foreign shares and bonds. Rebalancing was particularly tricky, because some of our funds owned stocks from more than one category. I longed for a simpler set of investments.

That brings me to 2009. Like many organizations—large and small—it seems my employer finally realized that its retirement plans were badly designed and included overpriced investments, and that upgrading those plans was an easy way to improve the benefits provided to employees.

Early that year, the State of North Carolina changed the firm handling its 457 plans from Great-West to Prudential Financial. Prudential offered an international index fund and a large-cap index fund, so I moved my 457 investments into those funds. Expenses weren’t as low as Vanguard’s comparable funds, but they were still much better than the cost of the actively managed funds on offer.

Then, also in early 2009, the University of North Carolina System (which consists of 16 Universities, including UNC at Chapel Hill, the flagship school where I worked) made changes to the way employees could invest. Previously, each school had some local investment groups through which non-faculty employees could invest. But starting in early 2009, Fidelity Investments took over responsibility for the 403(b) plans for most university system employees. (Faculty, as well as some employees, were instead covered by TIAA-CREF.) In return for getting the exclusive contract to handle these 403(b) plans, Fidelity was required to make a subset of Vanguard funds available to university employees.

I was delighted about these changes, and I immediately set about shifting my 403(b) into Vanguard funds. This wasn’t as easy as it sounds. As you might expect, Fidelity didn’t want people to use the Vanguard funds, since Vanguard was a direct competitor and Fidelity wasn’t making any money off the Vanguard funds. As a result, it required multiple phone calls to find someone who knew how to shift both my current account balance and future contributions to Vanguard, and then it took a great mound of paperwork to make it happen.

While I wasn’t able to access Vanguard’s Total Stock Market Index Fund through Fidelity, I was able to get its S&P 500 index fund, along with its mid-cap, small-cap, total bond market and total International stock index funds. This greatly simplified rebalancing, while also reducing fund expenses. I was one step closer to my goal of investing in a small set of low-cost index funds that together would provide a well-diversified portfolio that I could easily manage.

Brian White retired from the University of North Carolina, where he worked as a systems programmer and then director of information technology in the computer science department. His previous articles were Lesson Well Learned and Rookie Mistakes. Brian likes hiking with his wife in a nearby forest, dancing to rocking blues music, camping with friends and stamp collecting. He also enjoys doing volunteer income tax assistance (VITA) work in the Chapel Hill senior center.

Brian White retired from the University of North Carolina, where he worked as a systems programmer and then director of information technology in the computer science department. His previous articles were Lesson Well Learned and Rookie Mistakes. Brian likes hiking with his wife in a nearby forest, dancing to rocking blues music, camping with friends and stamp collecting. He also enjoys doing volunteer income tax assistance (VITA) work in the Chapel Hill senior center.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation. Want to receive daily email alerts about new articles? Click here. How about getting our weekly newsletter? Sign up now.

The post Limited Selection appeared first on HumbleDollar.

September 21, 2020

Staying in Bounds

INVESTING IS ALL about picking the “best” investments—or so I thought. It took a lot of years to realize that this was the wrong focus. Instead, selecting a portfolio of good, reliable investments and sticking with them is what really worked for me and for my clients.

Sound simple? It can be—but the maintenance is surprisingly hard. We’re talking here about periodic rebalancing. That involves setting target percentages for a portfolio’s various investments and then occasionally buying and selling, so you bring a portfolio back into line with those targets.

As my investment advisory business grew, keeping clients’ portfolios on track was taking a lot of work. That’s what got me interested in rebalancing theory. The article I found most informative was Marlena Lee’s 2008 study, Rebalancing and Returns, which became the basis for our rebalancing policy. From the article, I learned that rebalancing is complicated if you want to get the most from it. These are the questions you need to tackle:

How often will you look for rebalancing opportunities?

Which holdings will you rebalance?

Will you boost performance by rebalancing—and, if so, how do you maximize that?

How will you manage what can become a time-consuming process?

Some investors rebalance according to the calendar, meaning they might check their portfolio every month, every quarter or every year. But Lee’s article suggests a better strategy is to rebalance when a portfolio’s actual asset allocation strays beyond an acceptable limit. This limit is called the “rebalance band.”

The rebalance band is the range around the target allocation that’s deemed acceptable. According to Lee’s article, the rebalancing strategies that produced the highest returns were those that used a 20% rebalance band and looked for opportunities to rebalance every one, five or 10 days.

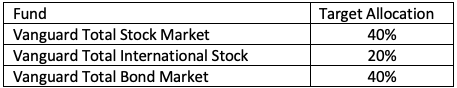

How might that work in practice? For a simple three index-fund portfolio, we might set these target allocations:

Let’s assume we use a 20% rebalance band, which means we don’t want an investment position to be 20% larger than our target or fall more than 20% below it. That means a trigger event occurs when the actual allocations are outside the following bands:

That still leaves us with the choice of how often to look. Lee’s data indicates it’s preferable to look as often as every trading day to every 10 days. At my firm, we settled on twice per month—roughly every 10 trading days—even though this increased our workload substantially compared to our earlier annual rebalancing.

Next, we were faced with the “what to rebalance” decision. Typically, if you rebalance according to the calendar, you rebalance all investments back to their target allocation. But with band rebalancing, we could rebalance the entire portfolio or just the asset classes that were currently outside their band. We decided to focus on rebalancing only those investments beyond their rebalance bands, though we made adjustments elsewhere if these trades left portfolios with too much uninvested cash or, alternatively, with too little cash to cover upcoming withdrawals.

We were extremely interested in any rebalancing premium. Maybe all this effort could result in better returns. Rebalancing and Returns reported a 0.24 percentage point increase in annual returns if you rebalanced twice a month using 20% rebalance bands, relative to the return you might get with annual rebalancing. Maybe that additional return shouldn’t be a big surprise: Looking twice a month provides more opportunities than annual rebalancing to sell asset classes that are high and buy those that are low.

The good news is, we had settled on a rebalancing policy. The bad news is, we had created an implementation nightmare.

For those of you managing your own portfolio, using a spreadsheet is a good option. But if you’re managing multiple portfolios for friends or clients, looking twice a month is going to be very time consuming. We chose to automate our spreadsheet and, over the years, it got better and faster. A better choice for advisors with 100-plus clients is licensing software. Some vendors include AdvisorPeak, iRebal, RedBlack Software, Tamarac and TRX (Total Rebalance Expert). A fortunate few will find that their custodian provides a free rebalancing tool.

The bottom line: Rebalancing is better than no rebalancing. Rebalancing when a portfolio is “out-of-band” is better than annual rebalancing. Consider using a 20% rebalance band. And looking twice a month for rebalancing opportunities may boost performance.

Rich Chambers is a Certified Financial Planner and the founder of Investor’s Capital Management, LLC. His began his career as a software engineer with IBM before becoming a financial advisor in 1999. Rich is now retired and lives near Lake Tahoe with his wife and their three pooches. He spends time birding and has just finished teaching a class, “Birding by Ear: Bird Sounds of Lake Tahoe.” Contact him via email at richc@advisorinnovation.com.

Rich Chambers is a Certified Financial Planner and the founder of Investor’s Capital Management, LLC. His began his career as a software engineer with IBM before becoming a financial advisor in 1999. Rich is now retired and lives near Lake Tahoe with his wife and their three pooches. He spends time birding and has just finished teaching a class, “Birding by Ear: Bird Sounds of Lake Tahoe.” Contact him via email at richc@advisorinnovation.com.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation. Want to receive daily email alerts about new articles? Click here. How about getting our weekly newsletter? Sign up now.

The post Staying in Bounds appeared first on HumbleDollar.

September 20, 2020

When to Change

IN THE BOOK OF JOAN, a tribute to the comedian Joan Rivers, her daughter Melissa shares some of her late mother’s quirks. Among them: Her mother always drove 40 miles per hour. Regardless of where she was—on the highway, in a school zone, in the driveway—she always drove 40 miles per hour. Melissa’s conclusion: For passengers, this could be hair-raising, but at least her mother was consistent.

When it comes to investing, consistency is definitely a virtue. It’s best to pick a strategy and stick with it. But the above story illustrates that consistency can also be risky. When carried too far, it can cross over into stubbornness—and that can be a problem.

As you manage your finances through this volatile period, you might be wondering where to draw that line. When should you stay true to your strategy and when does it make sense to change course? The world is a noisy and opinionated place. To make better decisions, I would turn down the volume on these five voices:

1. Expert opinions. At one point during the 1990s bull market, Federal Reserve Chair Alan Greenspan made headlines when he warned about “irrational exuberance.” But if you had heeded his warning, you wouldn’t have fared very well. Yes, the stock market eventually dropped—but not before it more than doubled in the three years following Greenspan’s warning. Even after the market finally slumped starting in early 2000, it never fell as low as it was on the day Greenspan made his famous remark. The lesson: No one, no matter how celebrated, knows the future. You might make a note of his or her view, but never treat it as gospel.

2. News media. It may seem like common sense to tune out the shrill voices on financial news channels. But a 1987 academic study actually proved this. Psychologist Paul Andreassen demonstrated that investors with more access to financial news engaged in more frequent trading and realized worse investment returns. People on TV might sound like they know what they’re talking about, but that still doesn’t mean their investment advice will be accurate.

3. Those with an agenda. In March, hedge fund manager Bill Ackman warned in a TV interview that “hell is coming.” Later, it was revealed that Ackman had a big short trade in place—that is, he was positioned to benefit from a further drop in stock prices. As you make financial decisions, keep in mind that those with a microphone in front of them might be using it to further their own goals, not yours.

4. Pessimists. Author Morgan Housel has pointed out that pessimists sound smarter than optimists: “In investing, a bull sounds like a reckless cheerleader, while a bear sounds like a sharp mind who has dug past the headlines.” It’s important to keep this phenomenon in mind as you weigh the onslaught of market opinions.

5. Political partisans. This election, more than others in recent memory, seems fraught with emotion. But according to a Vanguard Group analysis, market returns in election years don’t differ meaningfully from returns in non-election years. Ditto for the level of volatility. Vanguard’s conclusion: Yes, elections are a big deal, but not necessarily for your portfolio.

If the above are situations where you should turn down the volume, what would warrant a change in your financial plan? Here are three possible triggers:

Personal circumstances. This may seem like the most obvious reason to revisit your financial plan, but it’s often overlooked. That’s because, for most people, financial change occurs incrementally. But cumulatively, small changes can be transformative. That’s why it makes sense periodically to revisit the pillars of your financial plan. Where to begin? I’d start with an area that’s often overlooked: insurance. With apologies for being morbid, it’s worth confirming that your life and disability coverage are sized appropriately for your family’s current needs. If the size of your family or your nest egg has changed, it may be worth updating your coverage.

New information. I argued above that you should tune out TV talking heads and expert prognosticators. But that doesn’t mean you should tune out everything. If new and meaningful information comes to your attention, you shouldn’t feel anchored to past decisions. Suppose you’ve come to understand the true cost of a whole-life insurance policy or the risk level of a mutual fund you own. In such situations, you shouldn’t hesitate to make a change.

Structural change. Why are experts so ineffective at making predictions? Last week, fellow financial advisor Ben Carlson helped explain this phenomenon. In a nutshell, the problem is that the world is always changing. “The world of finance,” he says, “is littered with people who are experts on an earlier version of the world…. There are a handful of investment principles that are evergreen, but the market structure is constantly in a state of flux.”

This has always been the case, but it’s especially true this year. If the pandemic and the election weren’t dominating the headlines, the Federal Reserve’s dramatic new policies would be big news. For many investors, these changes warrant a different strategy. Again, if the facts have changed, you shouldn’t feel anchored to past decisions.

What if a change in your plan does seem warranted? For some situations—like the life insurance example above—there may be no reason to delay after you’ve gathered the facts and done your analysis. Similarly, if you identify a key risk in your investment life, I wouldn’t delay. Recently, for example, I saw a portfolio that had more than 25% allocated to one stock. It was a great stock—Amazon—but that’s still too big a position. That’s the sort of change you should make right away.

In other cases, however, a more gradual shift might be wiser. In his book Mastering the Market Cycle, Howard Marks encourages readers to think in nuanced—rather than binary—terms. “Get the market’s tendency on your side,” he writes. “The outcome will never be under your control, but if you invest when the market’s tendency is biased toward favorable, you’ll have the wind at your back….”

What does this mean in practice? In the investment world, people endlessly debate the importance of market valuations. Today, in particular, people are concerned that the stock market is overvalued. But the fact is, no valuation metric is perfect. While there’s some connection between valuations and future returns, that relationship isn’t ironclad—the Greenspan example being just one notable example.

That’s why, when it comes to portfolio changes, I think it makes sense to implement changes gradually. If you’re dollar-cost averaging into the market today, you might go a little more slowly than you would have six months ago. You might also favor market segments that are still depressed, like value stocks. Meanwhile, if you’re rebalancing your portfolio or withdrawing spending money, you might weight your sales toward the S&P 500, which has seen the biggest run-up and where valuations look most extended. But it doesn’t need to be all or nothing. As Marks says, just try to get the wind at your back.

The bottom line: Consistency is a good thing, but sometimes it does make sense to shift course. You don’t want to always drive the same speed. The key is knowing when to speed up and when to slow down.

Adam M. Grossman’s previous articles include Just Say No, Eyeing the Exit and Making Time. Adam is the founder of Mayport, a fixed-fee wealth management firm. In his series of free e-books, Adam advocates an evidence-based approach to personal finance. Follow Adam on Twitter @AdamMGrossman.

Adam M. Grossman’s previous articles include Just Say No, Eyeing the Exit and Making Time. Adam is the founder of Mayport, a fixed-fee wealth management firm. In his series of free e-books, Adam advocates an evidence-based approach to personal finance. Follow Adam on Twitter @AdamMGrossman.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation. Want to receive daily email alerts about new articles? Click here. How about getting our weekly newsletter? Sign up now.

The post When to Change appeared first on HumbleDollar.

September 19, 2020

My Regrets

EVERY SO OFTEN, I’m asked about my biggest investment mistakes—and I really don’t have much to say. Yes, like many others, I dabbled in individual stocks and actively managed mutual funds early in my investing career. Yes, like everybody who’s truly diversified, there are always parts of my portfolio that are generating disappointing short-term results. But such things don’t cause me any regrets.

Instead, as I look back, my big financial regrets fall into four buckets:

Pound foolish. Almost everybody insists they’re a careful spender. The size of their portfolio—or the lack thereof—often suggests otherwise. But trust me: I really am frugal, occasionally to my own detriment.

My biggest mistake was probably spending too little on my first home. I could have afforded a more expensive place, but the money involved made me uneasy. Result: I ended up buying a rundown house that, over the next two decades, cost me more in remodeling than the home’s original purchase price. And, even after all that money, it still wasn’t that great a home.

But—and I know this sounds odd—perhaps my most enduring folly has been vacuum cleaners. Every time I went to buy one, I was struck by the huge price difference between the cheap versions and the expensive models. How much worse could the cheap vacuum cleaners be? So I repeatedly bought them and suffered repeated disappointment. Last year, I decided to mend my ways and bought a $300 vacuum cleaner. It was money well spent.

Enthusiasms. As a kid, I used to collect stuff—Lego, vacation souvenirs, stamps. That urge to collect has never completely left me. Over the years, I’ve amassed limited edition prints, old economics books, presidential campaign posters and more. At one time, I even had a copy of every article I’d ever written, as well as a binder filled with all the student newspapers I edited while at Cambridge.

When I die, my children aren’t going to want this stuff. In fact, much of it I don’t want. Whenever I can unload some of these things without triggering too many regrets over the time and money wasted, I grab it. All this is a reminder of why money spent on experiences, rather than possessions, is so much better for happiness. Possessions may deliver an initial thrill when they’re first acquired, but all too quickly they can become a burden.

Unwarranted worries. When I was in my 20s, I married a graduate student and soon had two children, all while trying to live on a junior reporter’s salary in New York. Our finances were extremely tight—and I was aware of every penny we spent.

An example: I remember a family vacation to California in early 1991. We used airline miles to book the flights. We stayed with friends every night except one, thus saving on hotel costs. Still, for me, the trip was marred by worries that we were spending money we couldn’t afford. I came to hate that feeling.

With the benefit of hindsight, I now know much of my worrying was unnecessary. Today, I almost never fret about my finances, even when the stock market nosedives or I get hit with a large unexpected expense. For me, that sense of contentment is one of the best things that money can buy.

Unasked questions. While I haven’t made investment mistakes that I regret, I have made two other financial blunders that pain me. Both involve real estate.

The first happened almost three decades ago, when I bought my first home. My down payment was less than 20% of the home’s purchase price, so I needed private mortgage insurance (PMI). The mortgage lender suggested that, instead of paying PMI every month, I pay a single premium upfront that would be included in the total amount I was borrowing. A quick back-of-the-envelope calculation suggested the single premium would be a better deal than paying PMI every month until my home equity exceeded 20% of the home’s value, so I agreed.

But I should have asked more questions and I should have thought more about it. What if I moved sooner, or made extra principal payments, or refinanced? Needless to say, it turned out I would done better opting for the monthly PMI.

That brings me to the current question I wish I’d asked. I’m trying to sell my New York apartment. Twice, I’ve accepted offers—and twice the deals have fallen through, though for reasons peculiar to the potential buyers, rather than to the apartment itself.

Still, I’m kicking myself for not thinking about the difficulties of selling the apartment before I bought it. At the time of the purchase, I thought I’d be leaving the place feet first. But instead of waiting until then, I decided to move to Philadelphia to be closer to family and friends.

The upshot: I’ve discovered that—no matter how spacious the apartment, how great its location and how spectacular the view—it’s difficult to sell a co-op apartment that’s in a building geared toward older folks, and which comes with lots of rules and high monthly maintenance payments. One day, somebody will walk into the apartment and fall in love with the place, just as I did. But in the meantime, I’m left to regret the question I didn’t ask.

Latest Articles

HERE ARE THE SIX other articles published by HumbleDollar this week:

SUVs. Tattoos. Eating out. Smoking. Video games. Pets. Lottery tickets. Soda. Richard Quinn looks at 10 ways that Americans could potentially cut spending—and finds an extra $870,000 for retirement.

“It’s reasonable to think returns might be weak over the next five or 10 years for mega-cap tech stocks,” says Mike Zaccardi. “Maybe it’s time to make sure you have exposure to other areas of the global market.”

How much could you save by favoring ETFs over index mutual funds? Dennis Friedman ran the numbers on a $1 million portfolio—and the savings came to more than $20,000 over 25 years.

Interested in whole-life insurance? James McGlynn explains how to dial down the hefty sales commission—and build up cash value far faster.

“If you are a long-term investor, there’s a good chance you’ll be tested in the short term,” writes Tom Sedoric. “It’s crucial to stand your ground when algorithmic trading next makes the markets seem temporarily insane.”

Your 401(k) may soon offer funds that include private equity investments. Should you bite? Adam Grossman wouldn’t.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter @ClementsMoney and on Facebook. His most recent articles include Playing Dumb, Small Pleasures and Brain Candy.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter @ClementsMoney and on Facebook. His most recent articles include Playing Dumb, Small Pleasures and Brain Candy.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation. Want to receive daily email alerts about new articles? Click here. How about getting our weekly newsletter? Sign up now.

The post My Regrets appeared first on HumbleDollar.

September 18, 2020

A Combustible Mix

THERE’S NO SUBJECT that gets me more worked up than market volatility—and especially the danger posed by high-frequency trading (HFT). Volatility has become part of the “new normal,” thanks to fundamental changes in how the market operates.

Remember the flash crash of 2010? I haven’t forgotten the unsettling events of May 6, 2010, when the Dow Jones Industrial Average dropped 600 points in just five minutes. For a few minutes, starting around 2:45 p.m., prices entered an alternative universe that few could comprehend. One Dow Jones stalwart, Procter & Gamble, reached $100,000 a share, while otherwise strong companies such as Boston Beer and Accenture saw their stock temporarily drop to a mere one cent per share.

There was an equally fast recovery but, in my opinion, the damage to institutional credibility had already been done. The 2010 flash crash was one of the mileposts that reminds us that we live in a brave new world. The events of that day, which could have been far more catastrophic, were not the result of a so-called rogue trader or an accidental push of a button, but something more systematic.

It was a snapshot of what happens when the human side of order execution is superseded and overwhelmed by sophisticated computer algorithms. These algorithms can automatically kick into action across the market, some designed to protect existing investment positions, while others ruthlessly exploit mis-pricings. Many times, they’re designed for quick buys, sells and profits. When algorithms are involved, the profits or losses are made in nanoseconds.

It’s easy for many to regard the 2010 flash crash as an anomaly, but my 28 years as a financial advisor tells me that isn’t the case. Markets are analogous to oceans with species that make up a complex and interdependent ecosystem. When one of those species, algorithmic trading, becomes 70% of the ecosystem, the imbalance can potentially undermine the system’s overall health.

Normally, few would argue against increased liquidity—the ability, at any given moment, to find someone to take the other side of your trade. But the current environment is hardly ideal, because more liquidity than ever is based on HFT. One second, the price that’s being bid for a stock is good. The next second, the bid is gone. In my opinion, the HFT tail could be wagging the stock market dog. For shareholders and the overall economy, this is a sobering reality.

If we “enjoy” another flash crash, the psychological impact on investors could be significant. Never before have we seen such a dichotomy: Some investors, such as pension plans, endowments and 401(k) investors, are aiming for long-term returns, while others are eyeing micro-second chances to score a short-term profit.

When I began as a financial advisor almost three decades ago, the New York Stock Exchange had a specialist system whose job was to “provide a fair and orderly market.” Today, thanks to computerized algorithmic trading, anything goes. What does that mean for everyday investors? If you are indeed a long-term investor, there’s a good chance you’ll be tested in the short term—and it’s crucial to stand your ground when algorithmic trading next makes the markets seem temporarily insane.

Tom Sedoric is executive managing director of the

Sedoric Group

, a financial advisory firm in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. A Wisconsin native, he loves being on the water, knows some amazing card tricks and can fix just about anything.

Tom Sedoric is executive managing director of the

Sedoric Group

, a financial advisory firm in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. A Wisconsin native, he loves being on the water, knows some amazing card tricks and can fix just about anything.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation. Want to receive daily email alerts about new articles? Click here. How about getting our weekly newsletter? Sign up now.

The post A Combustible Mix appeared first on HumbleDollar.

September 17, 2020

Want $870,000?

SENTENCES THAT begin with “I can’t” drive me nuts—and I especially dislike the sentence, “I can’t save.”

“Pish-tosh,” I say. Every household in America earning at least the median income can save for the future. If they try hard, many lower-income Americans could also save.

Of course, the amount saved will vary, but even small amounts can help over the long haul. If a household earning $40,000 a year can sock away enough to generate $300 or $400 in monthly retirement income to supplement whatever they get from Social Security, that’s significant. Saving early and regularly quickly makes life far less financially stressful.

How can I be so confident that most Americans have the ability to save? Look around at the many nonessential businesses—including entertainment companies—that are sustained by the spending of the average American. I don’t advocate living like a hermit. But a touch of frugality and a sense of spending priorities wouldn’t go awry.

Last year, I wrote about the ways many people waste money. Earlier this year, I suggested “financial fasting” as a way to accumulate funds to start investing. But enough of theory. Let’s look at some numbers. For the 10 examples below, I assume a 40-year saving period, with those savings earning a 5% annual return.

1. The pause that refreshes. It amazes me how much soda makes its way into shopping carts. Americans consume 39 gallons of soda per person per year. Who needs all of that? Where I live, a case of 12-ounce cans is about $25. Skip one case a month and you can accumulate $38,000 in 40 years.

2. Light up (or not). Yes, smoking is down. But there are still 34 million smokers and they spend an average $6.28 a pack. Eliminating one pack a day will get you $291,000 after 40 years. Do that in New York City, where cigarettes are even more expensive, and you’ll be in a penthouse in Palm Beach at age 65.

3. Your turn. Video games are big business. Americans spend about $43 billion a year on games. The average player is in his or her mid-30s. Assume a player skips buying just two new high-end games each year. That will net about $11,000 for retirement.

4. Ink. A skilled tattoo artist earns around $200 an hour. The cost of a tattoo ranges from $30 to thousands. About a third of Americans, most of them under age 55, have at least one tattoo. Those with a tattoo typically have more than one. Let’s assume a onetime total tattoo cost of $500. Skip that and you’ll add $3,500 to your pot of gold.

5. Fluffy or Fido. Nobody is giving up their fur baby to save money. But if you aren’t already supporting that dependent to the tune of $1,000 a year, avoiding the expense could get you $127,000 for retirement.

6. Transportation. Most people can get around town without a pickup or an SUV. Save $100 a month on your car payments and retirement gets easier with an extra $152,000.

7. Caffeine fix. Give up one grande caramel macchiato at $4.50 a week and you can add another $30,000 to your financial security.

8. What’s the special? Hey, we all enjoy a good meal at a nice restaurant once in a while, just make the “while” a tad further apart. Skip one night out a month, so you save perhaps $35, and you’ll be dining in luxury at age 65 with an additional $53,000.

9. Cash in hand. Literally, that is. This is my favorite strategy and maybe the easiest: Simply save your change. Let’s be conservative and say 75 cents a day goes into a jar. After 40 years, almost $35,000 will be in your bank account.

10. You betcha. News flash: You aren’t going to win the big lottery and those occasional $30 “pick four” wins will be easily offset by your losses. While reports vary, it seems adults spend an average $1,000 a year on state lotteries. Invest that in a surer thing and you’ll have $127,000 in retirement.

Don’t laugh. I know some of these daily and monthly amounts are modest, but they add up. Saving and investing is possible for just about everyone. The power of compounding is real. Indeed, if you followed all 10 of my examples, you’d have some $870,000 after 40 years.

Richard Quinn blogs at QuinnsCommentary.com. Before retiring in 2010, Dick was a compensation and benefits executive. His previous articles include Taking Credit, Do as I Don’t and About That 4%. Follow Dick on Twitter @QuinnsComments.

Richard Quinn blogs at QuinnsCommentary.com. Before retiring in 2010, Dick was a compensation and benefits executive. His previous articles include Taking Credit, Do as I Don’t and About That 4%. Follow Dick on Twitter @QuinnsComments.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation. Want to receive daily email alerts about new articles? Click here. How about getting our weekly newsletter? Sign up now.

The post Want $870,000? appeared first on HumbleDollar.

September 16, 2020

It Sure Adds Up

MY FINANCIAL advisor has been on a mission to reduce my investment costs. He’s been replacing my low-cost, broad-based index mutual funds with the exchange-traded fund (ETF) version. He believes this will improve my investment returns over the long run.

For instance, if you own Vanguard Total International Stock Index Fund—a mutual fund—you’re currently paying 0.11% in annual expenses. But Vanguard’s ETF alternative charges just 0.08%, equal to a savings of three cents a year for every $100 invested. That might seem small, but my advisor assures me it can translate into significant savings over time.

You purchase mutual funds directly from the fund company involved, with the price set as of the 4 p.m. ET market close, while ETFs can be traded whenever the stock market is open. I believe switching to ETFs is the right thing to do. But I had doubts about how large the savings would turn out to be. It’s hard to imagine saving three cents a year on every $100 can amount to a whole lot of money.

The upshot: Using NerdWallet’s mutual fund fees calculator, I decided to see how higher costs can impact a hypothetical $1 million retirement portfolio that enjoys 9% annual stock returns and 3% bond returns over a 25-year period.

I used Vanguard mutual fund and ETF expense ratios to determine the estimated 25-year cost, basing the calculation on a hypothetical portfolio with the following initial asset allocation: Vanguard Total Stock Market Index 35%, Total Bond Market Index 35%, Total International Stock Index 15% and Total International Bond Index 15%. Thereafter, no further money was added, and the portfolio wasn’t rebalanced.

Result? Check out the accompanying table. Keep in mind that the ETF cost excludes the modest sum you might lose to the bid-ask spread when you buy or sell an ETF. What can we learn from the table?

Switching from mutual funds to ETFs is a worthwhile cost-cutting effort, saving $20,465 over 25 years.

Vanguard Total International Stock, even though that position is less than half the size of Vanguard Total Stock Market, proves to be significantly more costly. Remember, fund fees are based on a percentage of assets, so you pay a larger dollar amount as your balance grows. That, it seems, is the price you pay to own a better diversified portfolio.

When investing in higher-cost specialty funds, such as those focused on energy, real estate, gold and health care, you have to ask yourself whether they’re really worth the extra cost. In most cases, probably not. In the long run, you’re better off in low-cost broadly diversified funds.

One of the most important things to remember about investment costs is that they compound, just like your investment returns, except this compounding is hurting you. You lose not just the costs you pay in any given year, but also the growth that this money might have enjoyed in future. It’s called “opportunity cost”—the loss of potential gain. For some investors, it could be tens of thousands of dollars.

If you use a financial advisor, you should factor in that cost—on top of the fees you’re paying for your investments—to get a handle on your portfolio’s total cost. For instance, the current annual cost of Vanguard Personal Advisor Services is 0.3% of a portfolio’s value. For our hypothetical $1 million portfolio, that’s $3,000 just for the first year. Over 25 years, this cost will also compound—negatively. Is it worth paying for advice? The answer will vary with every investor. But it’s worth it to me.

Dennis Friedman retired from Boeing Satellite Systems after a 30-year career in manufacturing. Born in Ohio, Dennis is a California transplant with a bachelor’s degree in history and an MBA. A self-described “humble investor,” he likes reading historical novels and about personal finance. His previous articles include 11 Remodeling Tips, Trust but Verify and No Vacation. Follow Dennis on Twitter @DMFrie.

Dennis Friedman retired from Boeing Satellite Systems after a 30-year career in manufacturing. Born in Ohio, Dennis is a California transplant with a bachelor’s degree in history and an MBA. A self-described “humble investor,” he likes reading historical novels and about personal finance. His previous articles include 11 Remodeling Tips, Trust but Verify and No Vacation. Follow Dennis on Twitter @DMFrie.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation. Want to receive daily email alerts about new articles? Click here. How about getting our weekly newsletter? Sign up now.

The post It Sure Adds Up appeared first on HumbleDollar.

September 15, 2020

Fatten That Policy

I WORKED in the investment department of three different insurance companies. But I never had any interest in buying a whole-life insurance policy. I knew term insurance was the best way to get the maximum death benefit for my premium dollars.

Instead, as a mutual fund manager, I was always more interested in investing in the stock market. (That said, I didn’t invest in the first mutual fund I managed. Why not? I didn’t want to pay the 7% “load”—the upfront sales commission.)

But my attitude toward whole-life insurance changed six years ago. In researching retirement income issues—and getting an insurance license along the way—I learned about “blended” life insurance. Many whole-life policies let you take the policy’s base coverage and combine it with a paid-up additions (PUA) rider. That way, you can design a policy that pays a lower commission to the agent and delivers better value to the consumer.

Insurance agents can get commissions as high as 55% of the first year’s premium for selling a whole-life policy, whereas the commission on a paid-up addition might be as little as 3%. Result? If you add $1 to a whole-life policy using a PUA rider, almost the entire $1 gets added to the policy’s cash value.

That’s a huge benefit. Most whole-life policies accumulate cash value very slowly, similar to paying down a home mortgage in the early years, when very little of your monthly payment goes toward principal. If you’re interested in whole-life insurance, be sure to ask your agent about blended insurance policies.

But there’s a catch. In 1988, Congress changed the rules on life insurance to limit the premium amount that could be contributed to a policy in the first seven years, relative to the size of the death benefit. If you breach these legal limits, your policy could become a “modified endowment contract” and lose key tax advantages.

The legislation prompted insurance companies to devise blended policies as a workaround. These blended policies often involve not only PUA riders, but also a term life insurance rider that increases the death benefit, thus avoiding the risk that a policy will be deemed a modified endowment contract. Five years ago, I bought a blended policy that was roughly one-third whole-life and two-thirds term insurance, and then took advantage of the paid-up additions rider to rapidly build up the policy’s cash value. I’m now approaching the point where I can drop the term insurance without worrying that the policy will be considered a modified endowment contract.

Why go through all these machinations? As I see it, whole-life insurance is a unique fixed-income category. No matter which direction interest rates go, your cash value only increases. This was appealing to me, since I wanted a secure yield but was—and remain—fearful that interest rates could skyrocket someday.

My hope is to leave the policy untouched, so my children inherit the policy’s death benefit income-tax free. But if I need extra money later in retirement, I can tap into my policy’s cash value. That cash value will grow tax-deferred—and any withdrawals I make will be tax-free, provided I limit my withdrawals to the premiums I’ve paid.

On top of that, I’ll get dividends from the insurance company. These dividends are a strange beast. They’re never guaranteed. But for many top insurers, they’ve been paid since the Civil War. I think of the dividend partly as a return to policyholders of premiums that are set at an overly conservative level.

In addition, when other policyholders let their whole-life policies lapse—often because they find the premiums too steep—that results in excess profit that contributes to the dividends paid. In other words, the reason many people hate insurance companies is a reason I earn a higher dividend. This dividend can be paid out or reinvested in further paid-up additions. I expect the annual dividends I’ll receive will be equal to slightly over 3% of my policy’s cash value, which compares favorably with current high-quality bond yields.

James McGlynn, CFA, RICP, is chief executive of Next Quarter Century LLC in Fort Worth, Texas, a firm focused on helping clients make smarter decisions about long-term-care insurance, Social Security and other retirement planning issues. He was a mutual fund manager for 30 years. James is the author of Retirement Planning Tips for Baby Boomers. His previous articles include My Retirement, Early Decision and Your 10-Year Reward.

James McGlynn, CFA, RICP, is chief executive of Next Quarter Century LLC in Fort Worth, Texas, a firm focused on helping clients make smarter decisions about long-term-care insurance, Social Security and other retirement planning issues. He was a mutual fund manager for 30 years. James is the author of Retirement Planning Tips for Baby Boomers. His previous articles include My Retirement, Early Decision and Your 10-Year Reward.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation. Want to receive daily email alerts about new articles? Click here. How about getting our weekly newsletter? Sign up now.

The post Fatten That Policy appeared first on HumbleDollar.