Jonathan Clements's Blog, page 314

September 4, 2020

Stay in Your Lane

MICHAEL PHELPS and South Africa’s Chad le Clos had an intense rivalry. In 2012, le Clos took home the gold medal in the 200-meter butterfly. In 2016, they met again in the finals of the same event. A photographer captured the moment when Phelps was intent on winning gold, while le Clos seemed intent on watching Phelps.

How many times in life have we been more focused on what others were doing and how they’re doing it? How much more (fill in the blank) someone else is or how much more (fill in the blank) someone else has, causing us to lose our own focus and stumble? Research tells us that more than 10% of our daily thoughts are devoted to making comparisons of some kind.

This is precisely why I despise those charts and spreadsheets showcasing how much you “should” have accumulated for retirement based on your age and income, or how much the majority of people have saved by some specified age.

So what? So what if you don’t have the exact amount you “should” have by age 40? What good is it going to do to spend time and energy focused on why you don’t measure up to some arbitrary barometer of financial fitness? And what assumptions are used in determining the numbers to begin with? Does the chart account for the fact that you took two years out of the workforce to put yourself through graduate school? Or that your career has been non-linear? I doubt it.

Instead, let’s take a cue from Michael Phelps. Stay in your own financial lane. What have you already accomplished? What can you do more of? I’m talking about micro-actions that compound over time, like investing in yourself. Take the $6,000 you had earmarked for your Roth IRA contribution. Why don’t you use it to obtain additional qualifications or certifications? Your future earnings growth will likely far surpass the growth of that Roth contribution.

How can you spend more time doing what you’re good at? What systems can you put in place to make this happen? Where are you not strategically spending money that could make a crucial difference?

This is something I think about a lot. To date, I’ve allocated a good amount of money and time toward continual growth and self-improvement—coaches, fitness, books, conferences, certifications and formal education. But I don’t feel I’ve been as effective as I’d like in capturing, organizing and sharing the ideas, insights and connections I’ve gained through all these experiences, so that’s my focus today.

Perhaps one of the first micro-actions we can all take is removing “should” from our vocabulary. It’s such a limiting construct. Playing to someone else’s scoreboard is easy, which is why a lot of people do it. The harder thing—playing our own game—begins when we turn our focus and energy toward what we’re capable of and how we can improve ourselves. Sound simple? Yes, it is—but it isn’t easy.

Anika Hedstrom’s previous articles include Known and Unknown, Trek to Retirement and Simple but Not Easy. An assiduous researcher, Anika Hedstrom is a Certified Financial Planner who writes on the motivational and behavioral aspects of financial planning. Follow Anika on Twitter @AnikaHedstrom.

Anika Hedstrom’s previous articles include Known and Unknown, Trek to Retirement and Simple but Not Easy. An assiduous researcher, Anika Hedstrom is a Certified Financial Planner who writes on the motivational and behavioral aspects of financial planning. Follow Anika on Twitter @AnikaHedstrom.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation. Want to receive daily email alerts about new articles? Click here. How about getting our weekly newsletter? Sign up now.

The post Stay in Your Lane appeared first on HumbleDollar.

September 3, 2020

Debtors’ Prison

IT’S BEEN MORE than three years since my wife and I paid off the last of our consumer debt. Since then, we’ve enjoyed the benefits of a debt-free life: less stress, no interest payments and a lower cost of living.

While these reasons alone make a strong case for paying off credit card balances, car loans and other consumer debt, the true cost of borrowing goes beyond the obvious. Here are five drawbacks that I wish I’d considered before taking on debt:

1. Borrowing stifles creativity. Using debt to solve financial problems squelches the impetus for innovation. Plato called necessity the mother of invention. If you swear off debt, it forces you to be more creative and look at problems differently. It encourages the cultivation of frugality and do-it-yourself skills—and those provide lifelong benefits.

An example: The alternator on my car failed a few years ago. A trustworthy mechanic quoted the parts and work at more than $600. I’d been making great progress paying down debt and decided not to let this break my momentum. I purchased the car’s Haynes manual and bought a used alternator at a parts exchange. It took me the better part of a Saturday to change the alternator, but I learned a new skill, saved more than $500 and, years later, the car’s still running great.

2. Debt discourages long-term thinking. The way debt is packaged and marketed foments a short-term mindset. Debts are often structured to offer a monthly payment that most people would consider “reasonable.” Sometimes, debt payments are described as “low, easy” weekly payments. I’ve even seen payments quoted in daily amounts on par with pocket change, no doubt so consumers will infer that the amounts are trivial.

Meanwhile, I’ve never seen payment plans expressed in quarterly or annual amounts. When debt isn’t an option, it forces you to ponder the full cost of the item in question. For big-ticket purchases, forking over hard-earned cash is much more psychologically uncomfortable than committing to years of low, easy payments.

3. Financing a lifestyle is self-defeating. Using debt to appear wealthy often accomplishes just the opposite. Most of the possessions that are commonly thought of as status symbols tend to lose value quickly. As my precocious five-year-old is quick to remind me, “The depreciation curve is very steep.” (I think she’s been listening to me.)

What if you purchase these status symbols on credit? It’s a double whammy. The rapid loss of value is further exacerbated by the debt’s interest expense. As a strategy for accumulating wealth, using debt to finance an unaffordable lifestyle accomplishes just the opposite.

4. The long-term cost is huge. Consumer debt has costs that go beyond the interest rate. Consider the opportunity cost of making monthly car payments. According to Experian, the average new car payment is $554 a month. Assuming a 5% rate of return, that same monthly amount, invested over 30 years, would grow to some $450,000.

And that’s not all. These payments must be made with after-tax dollars—dollars that wouldn’t be taxed for years if families instead saved them in tax-deferred retirement accounts. Granted, there’s some value in owning nice things. But given the opportunity cost, I think alternatives deserve careful consideration.

5. Borrowing can become a bad habit. In his book Atomic Habits, James Clear emphasizes the incredible compounding power of consistently making small personal improvements over long periods of time. He suggests that developing habits is more powerful than setting goals. Why? Habits, once formed, become a part of a person’s identity, often manifested in a statement beginning, “I’m the type of person who….”

Unfortunately, bad habits share that same powerful compounding effect. Once a habit of funding lifestyle through debt has been formed, someone may begin identifying as the “type of person who’s always in debt.” Sadly, unless deliberate action is taken to change these habits, they can become someone’s default settings—with all the stress and financial cost that entails.

Don’t get me wrong: Debt can have productive uses, helping people to buy homes and college educations. Clearly, I’d rather go into debt than have my family go hungry. Under certain circumstances, debt may be the only answer. But in many cases, debt is merely convenient—not necessary—and it comes with costs that go far beyond the low, easy monthly payments.

Isaac Cathey i

s a public sector employee and professional pilot. The bulk of his financial knowledge comes from books by the likes of John Bogle and JL Collins. He spends his free time running, swimming, hiking, camping, biking with his children and doing DIY projects. His previous article was Crash Test.

Isaac Cathey i

s a public sector employee and professional pilot. The bulk of his financial knowledge comes from books by the likes of John Bogle and JL Collins. He spends his free time running, swimming, hiking, camping, biking with his children and doing DIY projects. His previous article was Crash Test.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation. Want to receive daily email alerts about new articles? Click here. How about getting our weekly newsletter? Sign up now.

The post Debtors’ Prison appeared first on HumbleDollar.

September 2, 2020

Decisions, Decisions

I’VE BEEN EMPLOYED fulltime for nearly three decades—and retirement is now on the horizon. That means I’m spending more time trying to figure out how best to generate retirement income.

One obstacle: I keep getting bogged down by the seemingly endless choices. Despite knowing how critical these decisions are, I often find myself throwing up my hands in frustration and opting to do nothing. My experience isn’t uncommon. Welcome to the paradox of choice: When faced with a host of options, often we simply avoid making any decision at all.

That brings me to my retirement plan. Fortunately, of the six key components, three come mostly choice-free:

Spousal income. My husband is already retired and receiving a pension, Social Security benefits and income from a rental property. The pension and Social Security are fixed monthly payments, while the rental income varies from month to month. These payments will continue for the rest of his life.

Health insurance. My spouse and I are covered by a plan through my current employer. Once I turn age 55, I can opt into an early retiree program allowing us to continue with the same coverage we have now until I reach age 65, when I’ll be eligible for Medicare. After that, we’ll receive a monthly benefit to cover the cost of a Medigap policy. This benefit will continue for both my husband and me for the rest of our lives.

Housing. When I retire, we’ll sell our current home and use the proceeds to pay down the mortgage on our retirement home. The only choice we’ll need to make at that point: Will we recast the mortgage and reduce our monthly payment or, instead, make one large payment toward the loan’s principal balance and keep our monthly payment the same?

The other three components of my retirement plan, meanwhile, come with a host of options:

Pension. I have a small pension from the first fulltime job I ever held. There are no choices for me to make regarding how my money is invested and I’m guaranteed to earn a 7.5% rate of return for as long as I have money in the account. What I need to decide is how and when to withdraw the money. I can take a lifetime monthly payment, a lump sum payout or a combination of the two.

The age at which I take the money out, and whether I opt for the lump sum, could be influenced by my health. If I were to die before taking any form of payment, my husband—as beneficiary—would only receive an amount equal to about 45% of the overall account value. As such, we’ve decided to prepare the paperwork for a lump-sum distribution option, but file it only if I find myself seriously ill. That would guarantee my husband would receive the account’s full value.

Social Security. Like most people, I’ll need to choose the age at which to begin Social Security benefits. This will partly hinge on what will trigger the biggest payout: Having been married twice, I could receive benefits based on my own work record or, alternatively, I could get spousal benefits based on the earnings record of either my husband or my ex-husband. I would receive a larger monthly check based on my own earnings record if I delay benefits until age 70. But that’s not true of spousal benefits. They stop increasing as of your full Social Security retirement age—67 for me.

My 403(b). Within my current employer’s 403(b) plan, there are no fewer than 50 different managed funds that I can invest in. The accounts range from highly conservative to highly volatile and I can divvy up my money amongst them however I want. When I retire, I’ll need to decide whether to leave my money where it is or roll it over to an IRA. Each of those options comes with its own set of choices and tradeoffs.

If I leave my money where it’s at, I’ll have the option to invest a percentage of it in an annuity with a guaranteed rate of return. I can also access the funds if I leave my employer at age 55 or later, without incurring the usual 10% early withdrawal penalty. On the other hand, if I roll the money into an IRA, I’ll have the freedom to put it into a wider variety of investment options. I could also choose to convert some of the funds to a Roth IRA. I would, however, likely be forced to wait until age 59½ before I could access the money penalty-free.

Kristine Hayes is a departmental manager at a small, liberal arts college. Her previous articles include Day by Day, Did It Myself and While at Home

. Kristine enjoys competitive pistol shooting and hanging out with her husband and their dogs.

Kristine Hayes is a departmental manager at a small, liberal arts college. Her previous articles include Day by Day, Did It Myself and While at Home

. Kristine enjoys competitive pistol shooting and hanging out with her husband and their dogs.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation. Want to receive daily email alerts about new articles? Click here. How about getting our weekly newsletter? Sign up now.

The post Decisions, Decisions appeared first on HumbleDollar.

September 1, 2020

August’s Hits

FORGET THE SUMMER doldrums. In terms of total page views, August was HumbleDollar’s third best month ever. What caught readers’ attention? Below are last month’s seven most popular articles, three of which were penned by the ever-insightful Adam Grossman:

Should you refinance your mortgage to take advantage of today’s rock-bottom interest rates? Rick Connor shows you how to run the numbers.

If you own a jumble of stocks, bond funds, ETFs and more, you need to figure out whether this adds up to a sensible portfolio. Adam Grossman explains how—using a seven-step process.

James McGlynn spent much of his career as a mutual fund manager. What’s he doing to prepare for retirement? Buying lots of insurance products.

“It seems we have critics saying that the 4% rule leads to both too little spending and too much,” notes Richard Quinn. “Neat trick, wouldn’t you say?”

The raconteur. The statistician. The gunslinger. The philosopher. Adam Grossman discusses four approaches to investing that seem promising, but often fail miserably.

“A prudent goal is to have no debt other than a home mortgage, and then pay off that mortgage as soon as feasible,” writes Tom Welsh. “I’d advise doing so even if it means you invest less in stocks.”

Worried your next money decision will turn out badly? Adam Grossman offers six strategies that’ll help you keep your financial regrets to a minimum.

What about our weekly newsletters? In August, the two most popular were Risking My Life and Take the Low Road.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter @ClementsMoney and on Facebook. His most recent articles include Brain Candy, Think Like Eeyore and Getting Emotional.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter @ClementsMoney and on Facebook. His most recent articles include Brain Candy, Think Like Eeyore and Getting Emotional.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation. Want to receive daily email alerts about new articles? Click here. How about getting our weekly newsletter? Sign up now.

The post August’s Hits appeared first on HumbleDollar.

August 31, 2020

Much Appreciated

WHAT’S YOUR CAPITAL gains tax rate? It’s a crucial number to know—and it could open the door to some big tax savings.

Most investors are aware that there’s a significant difference between the tax rate on short-term capital gains—investments held for a year or less—and that on long-term gains, those held more than a year. Realized short-term gains are dunned as ordinary income, just like your salary or any interest income you earn, while long-term appreciation gets taxed at a lower rate.

What’s less understood is how the relationship between capital gains and ordinary income—and the order in which they’re taxed—can impact your marginal tax rate. Understanding those rules can open up a host of tax planning opportunities.

Some background: Capital gains are part of your adjusted gross income, or AGI. Your AGI drives the tax rate you pay not only on ordinary income, but also on long-term gains. That capital gains rate will be lower than the rate on earned income. In fact, if your AGI is low enough to put you in the bottom two income tax brackets, your long-term capital gains tax rate will be zero, unless you’re right at the top of the 12% bracket.

From there, the capital gains rate jumps to 15% and then, at high levels of income, to 20%. On top of that, those with capital gains may face a 3.8% “net investment income tax,” also known as the Medicare surcharge or surtax, which kicks in at $200,000 for single individuals and $250,000 for those married filing jointly. The accompanying table shows 2020’s seven ordinary income brackets, three long-term capital gains brackets and two Medicare surcharge brackets.

The key thing to understand: Long-term capital gains are taxed as additional income, on top of your ordinary income, which means capital gains won’t push your ordinary income into a higher bracket. To see why that’s important, consider a married couple, Joe and Mary.

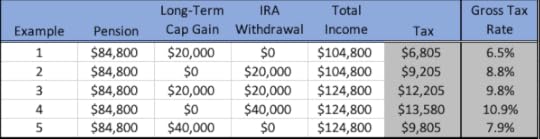

They’re retired with a pension of $84,800. After subtracting 2020’s standard deduction of $24,800, they’re left with taxable income of $60,000, which puts them in the 12% bracket. Their federal tax bill would be $6,805. If they also realized a $20,000 long-term capital gain, their income would increase to $104,800. Factoring in the standard deduction, that puts their taxable income at $80,000. That $80,000 still keeps them within the 0% long-term capital gains tax bracket, so the $20,000 gain triggers no extra tax and the amount owed to Uncle Sam remains at $6,805. Sweet deal, right?

What if they had chosen to make a $20,000 withdrawal from a traditional IRA, instead of realizing that capital gain. In that case, the entire $20,000 IRA withdrawal would be treated as ordinary income and taxed at their marginal rate of 12%. Result: Their tax bill would be $9,205, an increase of $2,400.

Now, let’s assume they needed $40,000 in additional income, so they took both the $20,000 IRA withdrawal and the $20,000 capital gain. This pushes their income to $124,800, or $100,000 after subtracting the standard deduction. This is $20,000 above the top of the 0% capital gains bracket, which caps out at $80,000, so their $20,000 long-term capital gain is now taxed at 15%, or $3,000, and their total tax bill would be $12,205.

What if, instead, they took a $40,000 IRA withdrawal? Again, their taxable income is $100,000, but now it’s all income and the amount over $80,250 is taxed at the 22% income tax rate, triggering a total tax bill of $13,580. What if they realized a $40,000 long-term capital gain? There’s no change in their total income, but the amount over $80,000 is now a capital gain taxed at 15% and their tax bill is $9,805. The table below details the five examples. It also includes Joe and Mary’s gross tax rate, which is their tax bill divided by their gross income.

(A digression: Joe and Mary’s capital gain isn’t just taxed at a lower rate, which means they have more left after taxes. On top of that, we’re talking here about the tax on their gain, not the total value of the investments sold. If Mary and Joe sold $40,000 in stock, the taxable portion might be, say, $15,000, assuming their cost basis on the stock was $25,000. Alternatively, if Mary and Joe wanted to net $40,000 after taxes, they’d need to sell more than $40,000 in stock. Let’s say they sold $45,300 of stock with a cost basis of $10,000, so their realized gain was $35,300. If that gain was taxed at 15%, they would be left with some $40,000 after the taxes on their $45,300 stock sale.)

Although simple, the above examples demonstrate that carefully analyzing which assets to draw on, and in what order, can make a significant difference to your tax bill. When does this kind of analysis come in handy? If you have a year with unusually high income, perhaps because of a Roth conversion or a big year-end bonus, realizing capital gains may be the better bet if you need extra cash. On the other hand, if your taxable income is unusually low—perhaps you just retired or you have high medical deductions—drawing on your retirement accounts, and generating more ordinary income, could be the smarter move.

What if you have an especially challenging situation to analyze? I’d recommend using tax software to make sure you capture all the complex interactions. And if you’re looking to minimize your overall tax burden, don’t forget about state taxes. For instance, my home state of Pennsylvania doesn’t tax retirement account withdrawals, but it does tax capital gains.

Richard Connor is

a semi-retired aerospace engineer with a keen interest in finance.

Rick enjoys a wide variety of other interests, including chasing grandkids, space, sports, travel, winemaking and reading. His previous articles include Victims of the Virus, Refi or Not and Working the Numbers

. Follow Rick on Twitter

@RConnor609

.

Richard Connor is

a semi-retired aerospace engineer with a keen interest in finance.

Rick enjoys a wide variety of other interests, including chasing grandkids, space, sports, travel, winemaking and reading. His previous articles include Victims of the Virus, Refi or Not and Working the Numbers

. Follow Rick on Twitter

@RConnor609

.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation. Want to receive daily email alerts about new articles? Click here. How about getting our weekly newsletter? Sign up now.

The post Much Appreciated appeared first on HumbleDollar.

August 30, 2020

Making Time

INVESTING IS JUST one ingredient for financial success. In fact, one of the best routes to financial security is also one of the most obvious: Increase your income.

In the middle of a pandemic, this might seem like a tall order. After all, most people’s work and home life have been turned upside down this year. But it’s for precisely that reason that I wanted to pull together the following time-tested strategies for increasing work productivity.

If your house looks anything like mine—with parents and children gearing up for another school year working from home—you might find these 10 strategies helpful for getting more done with less stress:

Step 1: Clearing the decks

David Allen, author of Getting Things Done , emphasizes one key point: Don’t try keeping things in your head. Why? Even if you have an excellent memory, you’ll unnecessarily consume mental energy trying to remember everything on your to-do list. The first step to greater productivity is perhaps the simplest: Offload as much as you can from your head onto a list. It doesn’t matter what form that list takes. It could be electronic or on paper. It just needs to be written down somewhere. In Allen’s view, this is the single best way to clear your mind, so you can focus on the task at hand.

Author Merlin Mann coined the term “Inbox Zero.” The idea, as you might guess, is to manage your inbox, rather than letting it manage you. Most important, don’t let unread emails pile up. In the same way that to-do list items in your head consume valuable mental space, unread emails can cause stress and even anxiety. Mann’s advice: To do your best work, develop a discipline to avoid letting emails linger. He explains how in this video.

Neuroscientists talk about novelty bias. In simple terms, the human brain is drawn to new things. That’s why the modern smartphone is, in many ways, the enemy of productivity. It is literally a distraction machine, ringing and buzzing all day. The simplest solution: Many people put their phones in another room when they need to concentrate. What if you need to be reachable for important calls? Use one of your phone’s built-in tools to silence social media and other distracting apps, while still allowing important calls through. On iPhones, it’s called Do Not Disturb, and on Android devices it’s called Focus Mode. A similar tool, called Freedom, accomplishes the same thing when you’re working at your computer.

Step 2: Getting to work

Public companies in the U.S. are required to issue financial reports every three months. In a lot of ways, this is onerous, but one benefit is that it ensures focus. That’s why many productivity gurus recommend taking a similar approach. In The ONE Thing , author Garry Keller suggests starting with your biggest long-term goal and then asking yourself, “What can I do this year to reach that goal?” Then work backward from there: “What can I do this quarter, and this month, and this week—and ultimately today—to move toward that goal?” In other words, be strategic with your time. Is this common sense? Yes. But today’s world is full of distractions, so it’s more important than ever to think strategically about time use.

Once you’ve decided something is important, what’s the best way to ensure that it gets done? Tony Robbins often says, “If you talk about it, it’s a dream. If you envision it, it’s possible. But if you schedule it, it’s real.” What he’s talking about is the distinction between a to-do list and a calendar. There’s a key difference. We all have long lists of things we’d like to do, and that’s fine. But Robbins’s advice is to regularly comb through those lists and to move the most important items off the list and onto your calendar. That’s when they’ll actually get done.

Robbins makes a good point about using a calendar. But how exactly should you structure your time? To the extent that you have control over your work schedule, I recommend the methodology laid out in Daniel Pink’s book When . In short, the idea is that humans all have biological clocks—but they differ from person to person. Pink’s recommendation: Conduct a self-audit of your own biology, then structure your schedule so you’re doing your most important work when you’ll be most effective.

Bill Gates and Elon Musk take this a step further. Both credit at least part of their success to “task batching.” The idea here is to minimize the number of times you have to change gears during the day. Many people’s workdays are consumed by an unpredictable assortment of meetings, emails, phone calls and interruptions from co-workers. The solution: Try to set aside a specific time for each type of activity. Instead of peppering your schedule with meetings, for example, schedule them all during one part of your day, or on specific days of the week. That will leave other parts of your calendar clear for undivided attention to other types of tasks. Result: When you spend less time transitioning back and forth between tasks, you’ll get everything done more quickly.

Step 3: Maintaining efficiency

Bob Pozen, a former president of Fidelity Investments, has written a number of books on finance. But his bestselling book is called Extreme Productivity. If you were to read one book on this topic, this would be it. His best advice: the mantra of OHIO—Only Handle It Once. Whether it’s an email or a request from a co-worker, Pozen’s advice is to deal with things on the spot, rather than leaving them for later. This is similar to Inbox Zero but goes further, boosting efficiency in an important way: If you take care of something from beginning to end, all at once, you’ll get it done more quickly than if you did some of it today and some of it tomorrow. That’s because, when you put something aside, then pick it up later, it takes time to figure out where you left off and get back into it. This won’t work for everything, but for small things, think OHIO.

A related concept is what Pozen calls “Good Enough.” The idea here is to avoid wasting time trying to dot every i when you’re working on a low-priority task. For Type A personalities, this can be difficult, but Pozen sees a big advantage to “overcoming perfectionism.” As he explains, “It may take you one day to do B+ work, but it may take you the rest of the week to bump it up to an A.” Pozen is careful to point out that the “Good Enough” rule applies only to items of low importance. You should, of course, do A work when it matters.

Suppose it’s late in the afternoon and you feel your motivation flagging. Pink, the author of When, has a great tip he calls “just five more.” Whether it’s a mountain of emails to read or messages to return, tell yourself, “Just five more.” The advantage: This strategy can often jumpstart motivation, with the result that “just five more” ends up being 10 or 15 more. “But even when that doesn’t happen,” Pink says, by doing five more, “you’ve still accomplished something.”

Adam M. Grossman’s previous articles include Portfolio Checkup, Don’t Feel Bad and Minimizing Regret

. Adam is the founder of

Mayport

, a fixed-fee wealth management firm. In his series of free

e-books

, Adam advocates an evidence-based approach to personal finance. Follow Adam on Twitter

@AdamMGrossman

.

Adam M. Grossman’s previous articles include Portfolio Checkup, Don’t Feel Bad and Minimizing Regret

. Adam is the founder of

Mayport

, a fixed-fee wealth management firm. In his series of free

e-books

, Adam advocates an evidence-based approach to personal finance. Follow Adam on Twitter

@AdamMGrossman

.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation. Want to receive daily email alerts about new articles? Click here. How about getting our weekly newsletter? Sign up now.

The post Making Time appeared first on HumbleDollar.

August 29, 2020

Brain Candy

IT SEEMS QUAINT now, but a quarter century ago conversations would often degenerate into arguments over facts. How much do homes typically appreciate? How much does the average American have saved by retirement? What does a nursing home cost? Such questions would trigger tedious debates built on anecdotal evidence and half-remembered newspaper articles.

But as my father—who died in 2009—often remarked during the final decade of his life, there’s no point anymore in arguing over facts. Instead, we can just go on the internet and find the answer. Even with the risk that we’ll trip across “fake news,” the internet remains an astonishing repository of information and insights, including financial insights.

Want to enrich your understanding of both your own finances and the financial world more broadly? Here’s a host of tools and charts that I find especially fascinating:

How your net worth compares. Using the Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finances, DQYDJ.com will tell you how your net worth—either with or without home equity—ranks relative to your fellow Americans. (In case you’re curious, DQYDJ stands for “don’t quit your day job.”)

How your income ranks. DQYDJ can also tell you how your individual income compares to other Americans, how your household ranks and how your income stacks up against those who are the same age.

What the S&P 500 has returned. For years, basic market performance data was hard to come by. Not anymore. DQYDJ has calculators that will tell you the total return for a specified period for the S&P 500 and the Wilshire 5000. Want to see year-by-year returns for stocks, bonds and cash? Check out this page maintained by New York University finance professor Aswath Damodaran.

Where valuations stand. You can get a quick snapshot for the S&P 500 from Multpl.com, which also offers a host of other great charts. Interested in how valuations compare across different national markets? Head to StarCapital.de.

What the S&P 500 companies might earn. This one is a little tricky to find. Go to this page on S&P Global’s website and then scroll down until you see the “additional info” link. There, you’ll find a link to the “index earnings” spreadsheet, which includes S&P’s earnings information for the S&P 500. I like to look at 12-month reported earnings per share and compare the forecasts to the S&P 500’s current level.

How investments are correlated. This matrix from Portfolio Visualizer highlights the value of bonds in diversifying a stock portfolio. A correlation of close to one means two investments are highly correlated, while a negative number means they tend to move in opposite directions. Some of Portfolio Visualizer’s tools are freely available, including its back-testing tool for looking at different portfolio mixes.

How much house you can afford. That’s pretty much the name of a calculator offered by HSH.com. When you purchase a house, closing costs are often the nasty surprise. You can get a handle on those with a calculator from SmartAsset.com.

How long your retirement nest egg might last. Check out the easy-to-use tool from Vanguard Group. Keep in mind that the tool uses historical returns—which may prove too rosy. Also try Vanguard’s retirement income calculator.

What if you’re trying to squeeze more income out of your nest egg? You might consider an immediate fixed annuity. You can find links to some online calculators in HumbleDollar’s money guide. And, as a last resort, there’s always a reverse mortgage. Find out how much that might pay you.

When to claim Social Security. Mike Piper of ObliviousInvestor.com—my go-to source whenever I’m stumped by a question about Social Security—has built a great calculator for figuring out when to claim benefits. Use the “click here” checkbox near the top of the page to analyze more complicated situations.

You can always ask Fred. The Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis allows you to look at all kinds of government and other data using its Federal Reserve Economic Data tool, otherwise known as FRED.

Among other things, you can see what’s happened to corporate profit margins, stock prices relative to the value of corporate assets, the expected inflation rate for the next 10 years and how home prices have fared. In addition, you can see total federal government debt as a percent of GDP—which is alarming. But you can also see how much the federal government owes if you exclude debt held by the government itself, such as the holdings of the 12 Federal Reserve Banks and the Social Security trust funds. As you’ll discover, that’s far less alarming.

Latest Articles

HERE ARE THE SIX other articles published by HumbleDollar this week:

What do you get when you buy a target-date retirement fund? Bill Ehart looks under the hood at Fidelity, Schwab and Vanguard—and discovers major differences.

A tortured tale in which Dick Quinn tries to get a refund for $3,100 of unused airline tickets—and, at least for the moment, finds himself $6,200 richer.

Looking to remodel your house? Dennis Friedman, who’s in the midst of an extensive home renovation, offers 11 tips.

If you own a jumble of stocks, bond funds, ETFs and more, you need to figure out whether this adds up to a sensible portfolio. Adam Grossman shows you how—using a seven-step process.

Kyle McIntosh just left the corporate world to become a university lecturer. Thinking of making your own career switch? Kyle offers five pointers.

What do record low Treasury yields mean for everyday Americans? Mike Zaccardi counts the ways.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter @ClementsMoney and on Facebook. His most recent articles include Think Like Eeyore, Getting Emotional and Risking My Life.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter @ClementsMoney and on Facebook. His most recent articles include Think Like Eeyore, Getting Emotional and Risking My Life.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation. Want to receive daily email alerts about new articles? Click here. How about getting our weekly newsletter? Sign up now.

The post Brain Candy appeared first on HumbleDollar.

August 28, 2020

Ripple Effects

I STILL CONSIDER myself one of the younger folks at the energy trading firm where I work. The more tenured employees will sometimes talk about the early 1980s, when mortgage rates were north of 10%. “Try paying that down quickly,” they’ll quip, as we watch the 10-year Treasury note yield scroll by on the ticker—at around 0.7%.

I never thought interest rates would stay this low, especially given the recovery since March by both the stock market and many economic indicators. Just recently, the ISM manufacturing and services indexes were at 16-month and 17-month highs, respectively, though many pundits say the U.S. economy won’t fully recover from the COVID-19 crash until perhaps late 2021.

Still, for now, Treasurys are basically at all-time lows, no matter which part of the yield curve you look at—and that has five major implications:

1. A negative real risk-free rate. The yield on Treasury bonds, especially the 10-year note, is often considered the risk-free rate, meaning it’s the return you can earn while taking minimal risk.

But that risk-free rate isn’t looking terribly tempting. Annual inflation is running at just 1%. Inflation expectations for the next five years are under 2%. Nonetheless, those inflation rates are above both short- and intermediate-term Treasury yields. That means the after-inflation “real” interest rate on Treasurys is below 0%.

To earn inflation-beating gains, savers are relegated to taking more risk in higher-yielding corporate bonds or even the stock market. And, no, the bank isn’t an alternative: During much of the 1980s and 1990s, savings accounts earned 1% to 4% after inflation. Today, the real yield at many banks is often more like negative 1%.

2. Stock valuations are higher. Stock market bears love posting charts of the S&P 500’s price-earnings (P/E) multiple. Right now, it’s sky high, no doubt about it. But a key factor in determining stock valuations is current interest rates, especially Treasury yields. The lower those yields, the higher stock valuations tend to climb.

Recall the early 1980s again—when the 10-year Treasury yield was 15% and the stock market traded below eight times earnings. Jump ahead to today, and the S&P 500 trades at 35 times the past year’s reported earnings, in large part because corporate profits are so depressed. Good luck to those waiting for a return of single-digit P/E ratios on the S&P 500. Unless interest rates rise sharply, it’s very unlikely to happen.

3. Government debt isn’t a big risk—for now. U.S. government debt has soared to nearly $27 trillion. But take heart, it’s nothing to lose sleep over. You should be concerned about your health, how your kids are doing in school and paying the bills, not your share of government debt. Thanks to rock-bottom Treasury yields, the interest our nation pays remains manageable.

4. Mortgage rates are dirt cheap. I’m not looking to buy a house anytime soon. But for those in the market, what a time it is to be alive. Thanks to low Treasury yields, which are used to benchmark mortgage rates, borrowing costs are tiny.

Freddie Mac reports the average 30-year fixed rate mortgage rate is around 3% and the typical 15-year loan is close to 2.5%. If inflation ever ticks back up to its 50-year average of 3.9%, you’d be paying a lower mortgage rate than inflation. Already own a home? Consider refinancing if your mortgage rate is north of 4% and you still have a big outstanding loan balance.

5. A weaker U.S. dollar. Market watcher that I am, it’s hard not to notice the drop in the dollar over the past few months. Gold stocks and raw commodities surged earlier this summer. Emerging market stocks were even beating U.S. shares for a time. Falling interest rates mean foreign investors are less inclined to put money to work in Treasurys, so demand for the greenback has waned.

Borrowers, savers, retirees, young investors and international travelers (if that’s even a thing anymore) are all affected by these unprecedented low interest rates. Maybe one day I’ll be that tenured guy at the office, telling the youngsters about the good old days of a 2.5% mortgage.

Mike Zaccardi is a portfolio manager at an energy trading firm and a finance instructor at the University of North Florida.

He also works as a consultant to financial advisors on an hourly basis, helping with portfolio analysis and financial planning. Mike is a Chartered Financial Analyst and Chartered Market Technician, and has passed the coursework for the Certified Financial Planner program. His previous articles include Raw Deal, Cooking Up a Story and Please Ignore This. Follow Mike on Twitter @MikeZaccardi, connect with him via LinkedIn and email him at MikeCZaccardi@gmail.com.

Mike Zaccardi is a portfolio manager at an energy trading firm and a finance instructor at the University of North Florida.

He also works as a consultant to financial advisors on an hourly basis, helping with portfolio analysis and financial planning. Mike is a Chartered Financial Analyst and Chartered Market Technician, and has passed the coursework for the Certified Financial Planner program. His previous articles include Raw Deal, Cooking Up a Story and Please Ignore This. Follow Mike on Twitter @MikeZaccardi, connect with him via LinkedIn and email him at MikeCZaccardi@gmail.com.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation. Want to receive daily email alerts about new articles? Click here. How about getting our weekly newsletter? Sign up now.

The post Ripple Effects appeared first on HumbleDollar.

August 27, 2020

Different Strokes

TARGET-DATE FUNDS offer one-stop investment shopping. But what exactly are you buying?

These funds are intended to offer a diversified portfolio that’ll carry you through to retirement and beyond. Each follows a “glide path,” reducing its stock exposure over time. But the substantial differences among the funds means that some roads will be rockier than others, so it’s important to understand what you’re getting.

For instance, young investors in 2060 target-date funds—like my children—will have 90% or more in stocks. Over the next four decades, as the targeted 2060 retirement date approaches, that percentage will decline. But at the designated retirement date, some funds will leave 50% in stocks, while others will go as low as 40%.

Target-date funds can be a great set-it-and-forget-it solution for 401(k) and IRA investors. But as you’ll see from the accompanying chart, expense ratios and asset mixes differ significantly. Fund companies typically build their target-date funds by investing in other funds that the firm manages. I’m not aware of any target-date exchange-traded funds, so investors will need to park their money with the fund family that offers their chosen mutual fund. That makes buying these funds more of a commitment.

For this article, I examined three major firms that offer low-cost retirement-date funds—Charles Schwab, Fidelity Investments and Vanguard Group—focusing particularly on their 2020 and 2040 funds. All three have a series of target funds built using index funds. But Fidelity also offers actively managed target funds, while Schwab has a second lineup of target funds that mixes active and index funds.

For this article, I examined three major firms that offer low-cost retirement-date funds—Charles Schwab, Fidelity Investments and Vanguard Group—focusing particularly on their 2020 and 2040 funds. All three have a series of target funds built using index funds. But Fidelity also offers actively managed target funds, while Schwab has a second lineup of target funds that mixes active and index funds.

In their target-date index funds, Vanguard and Fidelity offer the purest approach. While your stock weighting will gradually fall as you age, that exposure comes in the form of total U.S. and total international stock index funds. That means there’s no tweaking of, say, the weight given to emerging markets.

It’s a different story at Schwab, and also among Fidelity’s actively managed target funds. Schwab Target 2020 Index Fund has emerging markets exposure equal to just 1% of its stock holdings, according to Morningstar. By contrast, Fidelity’s actively managed target funds make a huge bet on emerging markets, with Fidelity Freedom 2020 allocating 17% of its stock market money to developing countries.

As I wrote a few months ago, that’s an astonishing overweight—and not one I’m comfortable with, prompting me to cut back on Fidelity’s target-date funds in my 401(k). Vanguard’s founder and the father of indexing, the late Jack Bogle, said funds with higher expenses often take greater risk in hopes that higher returns will obscure their cost to investors. That may be the case with Fidelity’s actively managed target funds.

The differences aren’t just about emerging markets. There are also variations when it comes to things like foreign bonds, credit quality, real estate and commodities exposure.

In Vanguard’s retirement-date products, you’ll find the firm’s Total International Bond Index Fund, which includes slight exposure to emerging markets bonds. For instance, Vanguard Target Retirement 2020 has 13% in overseas bonds. Meanwhile, Schwab’s target funds have no dedicated foreign bond exposure, Fidelity’s active funds have a small allocation and Fidelity’s index funds have none.

What about bond credit quality? Though fixed-income investments are just 6% of its portfolio, the actively managed Fidelity Freedom 2040 Fund takes a couple of steps out on the credit quality limb. According to Morningstar, its overall credit rating is just BB—one notch below investment grade. (AAA is the highest bond rating, followed by AA, A and then BBB, which is the lowest rung of investment grade.) The target funds built using index funds tend to have the best credit rating among those in the accompanying chart, with most at a solid AA.

Schwab apparently believes real estate deserves extra emphasis. Both of its 2040 funds have 8% of their stock holdings in real estate securities, double the 4% in Vanguard’s offering. Meanwhile, alone among the three firms, Fidelity offers dedicated exposure to commodities in its actively managed target funds. For instance, the Fidelity Freedom 2040 Fund has nearly 2.5% in the Fidelity Series Commodity Strategies Fund.

The bottom line: Be sure to check under the hood. Fundamental asset allocation decisions by these big firms will take you on very different journeys as you head toward retirement—and you should make sure you are comfortable with what you’re buying and with the expenses you’ll end up paying.

William Ehart is a journalist in the Washington, D.C., area. Bill’s previous articles include Needing to Know, Played for Fools and Right from Wrong. In his spare time, he enjoys writing for beginning and intermediate investors on why they should invest and how simple it can be, despite all the financial noise. Follow Bill on Twitter @BillEhart.

William Ehart is a journalist in the Washington, D.C., area. Bill’s previous articles include Needing to Know, Played for Fools and Right from Wrong. In his spare time, he enjoys writing for beginning and intermediate investors on why they should invest and how simple it can be, despite all the financial noise. Follow Bill on Twitter @BillEhart.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation. Want to receive daily email alerts about new articles? Click here. How about getting our weekly newsletter? Sign up now.

The post Different Strokes appeared first on HumbleDollar.

August 26, 2020

Shifting Gears

AFTER 23 YEARS working in corporate finance for companies such as Amgen and Patagonia, I’m making a career switch this fall, becoming a fulltime lecturer at California Lutheran University. While I always enjoyed my corporate roles and liked my colleagues, I’ve long had a passion for teaching and wanted to make it my fulltime work.

While some co-workers and friends assumed this change was an impulsive decision driven by a midlife crisis or brought on by some epiphany while working at home during the pandemic, it was actually years in the planning. Hoping to make a similar career shift? Based on my experience, here are five important steps to take.

1. Develop a plan with your family. Depending on your personal situation, a career change may impact more than just you. While there should be positives to aligning your passion with your daily work, there could also be downsides, including lost income or a new work schedule. For the downsides that are an unavoidable part of your new career, such as a lower income, you need to decide whether the negatives are outweighed by the positives—and you need to do so as a family.

2. Test-drive your new career. Before making a significant job change, it’s critical to check that you’re truly interested. This may involve taking a class, doing part-time work or volunteering. You may have a blind spot, seeing only the benefits. Your best bet to identify unseen issues is with hands-on work in your new chosen career. In my case, I was able to teach four semesters on a part-time basis, while continuing my corporate role. This time in the classroom—as well as behind the scenes grading papers and preparing for classes—showed me that this was the career path I wanted to pursue. On top of that, I gained valuable experience that made me a viable job candidate.

3. Reconsider retirement contributions. A career switch may come with a short- or long-term cut in pay. To help offset that reduction, you may need to scale back contributions to tax-advantaged accounts like 401(k) and 529 plans to maintain your lifestyle. While I know that this approach is heresy in the financial planning world, I see such reductions as a reasonable choice if it’s necessary to pursue your passion, provided you can still achieve your long-term savings goals. In my case, I’m somewhat ahead of where I should be financially, thanks to maxing out contributions to my 401(k) for most of the past 23 years. While more will be needed for retirement, I believe I’ll be in a good long-term position, even if I don’t contribute up to the IRS limit over the next few years.

4. Defer income. While not available to everyone, some companies offer deferred compensation plans that allow you to defer current income into the years following your departure, which can have tax benefits if you expect your income to be lower in future years. Knowing I’d likely be making a career shift to a lower-paying role, I saved a small amount of my salary in the company’s deferred compensation plan over the last five years. In 2021 and 2022, I’ll receive this deferred compensation, which will be taxed at a lower rate than when I was in my corporate job. This income will also partially offset my new teaching position’s reduced pay.

5. Just do it. I’d urge readers not to overanalyze their situation. There’s always more you could save, as well as countless reasons you can think up to resist making a change. My view: If you have a well-thought-out plan, you’ve gotten yourself to a good place financially, and your gut tells you it’s the right choice, you should take the leap when the right opportunity comes your way.

Kyle McIntosh, CPA, MBA, is a fulltime lecturer at the California Lutheran University School of Management. He turned his career focus to teaching after 23 years working in accounting and finance roles for large corporations. Kyle lives in Southern California with his wife, two children and their overly friendly goldendoodle.

Kyle McIntosh, CPA, MBA, is a fulltime lecturer at the California Lutheran University School of Management. He turned his career focus to teaching after 23 years working in accounting and finance roles for large corporations. Kyle lives in Southern California with his wife, two children and their overly friendly goldendoodle.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation. Want to receive daily email alerts about new articles? Click here. How about getting our weekly newsletter? Sign up now.

The post Shifting Gears appeared first on HumbleDollar.