Jonathan Clements's Blog, page 307

November 13, 2020

Not Your Job

Problem is, this framing is based on three myths.

Myth No. 1: Your job is to outwit the financial markets.

Underlying this is the notion that the key to investment success is to have rare insights and expertise not shared by anyone else, along with nerves of steel and almost supernatural timing ability. “Star” fund managers trade on this perception, promoting their talent in picking tomorrow’s winners. As we know from painful experience, such stars tend to burn brightly before crashing to earth.

The fact is, markets are highly competitive. Millions of participants, including armies of rocket scientists and savants, buy and sell stocks, bonds and other securities every moment of every trading day in pursuit of an advantage. Algorithmic trading systems seek a timing advantage measured in micro-seconds.

Result? All publicly available information—from earnings news to economic data to the published opinion of every stock analyst and economist—is already baked into market prices. Outguessing the market requires that you have profitable information that no one else has—and that you can predict how the market will react to that information. And remember, getting it right just once isn’t enough. You have to do it over and over again.

There’s an element of Don Quixote to market-beating wannabees. They imagine they have an elusive and mystical edge that nobody else has. In reality, those who go out every day, like the Man of La Mancha, with the intention of beating the market only risk making a fool of themselves.

Of course, there will always be individual managers who do better than their benchmark in any given year. But there’s also plenty of evidence from academic studies that the winners don’t tend to repeat. On top of that, it’s hard to separate those with skill from those who are merely lucky.

Standard & Poor’s produces a regular scorecard comparing the performance of active managers to index returns. This consistently shows that most struggle to outperform common benchmarks. For instance, 80% of actively managed U.S. stock funds trailed the broad U.S. market over the five years through June 30.

This isn’t just a U.S. phenomenon. In the five years through year-end 2019, more than 77% of European stock funds lagged behind the S&P Europe 350 index. Over three years, it was closer to 80%. Even over one year, more than 70% of managers underperformed.

U.K. funds did better—at least over one year. In 2019, 73% of actively managed stock funds beat the S&P United Kingdom BMI. But take the comparison out over 10 years and the proportion of U.K. managers beating the market was less than a third.

Myth No. 2: Top fund managers happily share the fruits of their hard work.

Let’s say you decide you aren’t going to put your money with index-lagging managers. Instead, you’ll only invest with the stars. Moreover, let’s go even further and assume that you are indeed able to pick the future stars ahead of time.

Now ask yourself: If these managers are so good, why would they be charitable and share the additional value they capture with you? A stock-picker with the rare ability to identify winners year after year would presumably charge a significant fee for his or her service. Those fees typically absorb most of the additional return, or “alpha,” that these managers earn, leaving relatively little for their investors.

Myth No. 3: Success is hurdling some market benchmark.

You’ll likely find that some years you do better than the stock market averages and some years you fall short, usually without any change in effort on your part. Much will hinge on how your assets are allocated among and within stocks, bonds, cash and real estate, as well as how much you pay in investment costs.

For instance, if your portfolio is 40% in safe government bonds in a year when stocks soar, you aren’t going to do as well as your neighbor who’s 100% in stocks. Conversely, in a bad year for share prices, your portfolio is going to do significantly better.

But all this is a big distraction. Your real benchmark isn’t beating the stock market. Instead, it’s how you’re performing relative to the goals that you’ve set. This approach may not sound as heroic and sexy as the image of the individual investor bravely second-guessing the market. But it will almost certainly yield superior long-term results.

Robin Powell is an award-winning journalist. He's a campaigner for positive change in global investing, advocating for better investor education and greater transparency. Robin is the editor of

The Evidence-Based Investor

, which is where a version of this article first appeared. Regis Media owns the copyright to the above article, which can't be republished without permission. Robin's previous articles include Yesterday Once More, No Need to Guess and What's the Plan. Follow Robin on Twitter @RobinJPowell.

Robin Powell is an award-winning journalist. He's a campaigner for positive change in global investing, advocating for better investor education and greater transparency. Robin is the editor of

The Evidence-Based Investor

, which is where a version of this article first appeared. Regis Media owns the copyright to the above article, which can't be republished without permission. Robin's previous articles include Yesterday Once More, No Need to Guess and What's the Plan. Follow Robin on Twitter @RobinJPowell.The post Not Your Job appeared first on HumbleDollar.

November 12, 2020

That Monthly Check

Want a refresher? Here’s a look at both topics:

Working while collecting. If you start Social Security benefits before you reach your full retirement age (FRA), which is age 66 or 67 depending on the year you were born, your benefits are reduced—or withheld, as the Social Security Administration terms it—if you earn “too much.”

In 2020, the maximum you can earn without any reduction is $18,240. If you earn more than $18,240, you would lose $1 in benefits for every $2 you earn above $18,240. Suppose you have a $2,000 monthly benefit. If you made $66,240, you’d lose all benefits for the year. For this so-called earnings test, the allowable earnings are adjusted each year for inflation.

There’s a special rule for the first year you start collecting Social Security. Let’s say you retire mid-year and you’ve already earned more than 2020’s $18,240 limit. Under the special first-year rule, you can get a full Social Security check for any whole month you’re retired, regardless of your earnings earlier in the year. As long as your monthly earnings are less than that year’s maximum monthly earnings, you get your full check. In 2020, the maximum monthly earnings are $1,520, equal to $18,240 divided by 12 months.

The government also cuts you some slack in the year you reach your FRA. In that year, you could earn $48,600 in 2020 without any reduction. Above $48,600, you would lose $1 in monthly benefits for every $3 you earn above $48,600, up until the month you reach your FRA. Once you reach your FRA, you can earn as much as you want without any reduction in your monthly benefit.

What counts as earnings? Social Security includes the wages you make from your job or your net profit if you're self-employed. Also included are bonuses, commissions and vacation pay. What about pensions, annuities, investment income and other government benefits, such as military retirement benefits? Those don’t count.

The benefits that were withheld aren’t necessarily lost forever. Once you reach your FRA, your monthly benefit is adjusted upward to reflect the benefits surrendered over the prior years. But the withheld benefits aren’t returned right away. Instead, they’re spread over your expected lifetime.

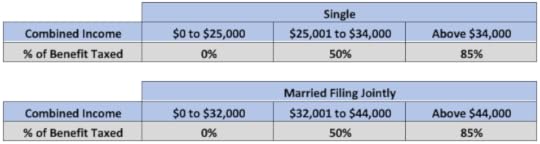

Taxing times. I’ve met many seniors who are surprised that a portion of their Social Security benefits can be taxed. Since 1983, up to 50% of benefits are taxed. Legislation enacted in 1993 increased the portion of benefits that could be taxed to a maximum 85%. This is regardless of your age, and it’s determined solely by your income level and filing status.

The notion seems straightforward, but it’s a little tricky in practice. For each filing status, there are two thresholds that determine how much is taxable. The tables below show the thresholds for taxpayers who are single and married filing jointly. These thresholds aren’t indexed for inflation, which means that with every passing year Social Security taxation is becoming an issue for more retirees.

Consider a married couple with “combined income” of $31,000, which consists of $11,000 in IRA withdrawals and $40,000 in Social Security benefits. Yes, I know that sounds odd, but I’ll explain in a minute.

As you’ll see from the table above, this $31,000 in combined income falls within the 0% box, so their $40,000 in Social Security benefits aren’t taxed. On the other hand, if their combined income was $38,000, that would put them in the middle of the 50% box. Because $38,000 is $6,000 more than the $32,000 threshold, 50% of that $6,000 would be taxable. Result: $3,000 of their $40,000 in Social Security would be hit with federal income taxes.

What if their combined income was $46,000? That would not only fully use up the 50% taxation zone—which spans $12,000 from $32,001 to $44,000—but also puts them $2,000 over the $44,000 limit and hence in the 85% zone. Result? First, you take 50% of $12,000, which is $6,000. Next, you calculate 85% of the $2,000 above $44,000, which is $1,700. Add together those two amounts ($6,000 plus $1,700) and you find that $7,700 of their $40,000 in Social Security benefits would be taxable income.

Got all that? Now comes an even trickier part: calculating your combined income. The Social Security Administration defines combined income as adjusted gross income, plus nontaxable interest from municipal bonds, plus half of your Social Security benefit.

In practice, it’s a bit more complicated than this equation implies. IRS Form 1040 has a worksheet that’ll do it for you. It requires your income sources from your 1040 (wages, interest, dividends, pensions, IRA withdrawals and so on), as well as the additional income sources from Schedule 1. You can reduce your combined income with adjustments listed on Schedule 1.

Understanding how this works may open up some tax planning opportunities. Consider the couple in the example above, with their combined income of $46,000. For simplicity’s sake, assume they have just two income sources: their $40,000 in Social Security benefits and $26,000 in traditional IRA withdrawals. Recall that only half of their Social Security is used in calculating combined income and thus, while their total income might be $66,000, their combined income for purposes of Social Security taxation is just $46,000. Also recall that $7,700 of their Social Security is taxable.

What if they needed $5,000 in additional income? If they took further money from their traditional IRA, that would increase their combined income by $5,000—causing an additional $4,250 of their Social Security benefits to count as taxable income. The upshot: A $5,000 taxable IRA withdrawal turns into $9,250 of extra taxable income. What to do? If it’s an option, our couple might tap their Roth IRA instead or, alternatively, opt to sell taxable account investments with little or no embedded capital gains.

Richard Connor is a semi-retired aerospace engineer with a keen interest in finance. Rick enjoys a wide variety of other interests, including chasing grandkids, space, sports, travel, winemaking and reading. His previous articles include Margin of Safety, State of Taxation and Paradise Lost. Follow Rick on Twitter @RConnor609.

Richard Connor is a semi-retired aerospace engineer with a keen interest in finance. Rick enjoys a wide variety of other interests, including chasing grandkids, space, sports, travel, winemaking and reading. His previous articles include Margin of Safety, State of Taxation and Paradise Lost. Follow Rick on Twitter @RConnor609.The post That Monthly Check appeared first on HumbleDollar.

November 11, 2020

Sinking Feeling

Students could only offer bids. No commentary, cooperation or deal-making were allowed.

The highest bidder paid me the money and received the $10.

The second-highest bidder had to pay me their final bid but got nothing.

I ran such auctions for 20 years and it almost always had three stages.

Phase 1: Many students dabbled with bids in increments of five or 50 cents, slowly inching the price up.

Phase 2: The dabblers dropped out and only the “serious” players remained, usually getting the price up to $5 or $6.

Phase 3: The trap springs. Misha bids $6. Ben counters with $7. Misha, realizing she’s looking at paying $6 while getting nothing back, is forced to outbid Ben and goes to $8. Ben decides to finish it by bidding $9.99. Misha does some quick math and decides to bid $10 to break even, rather than pay $8.

But wait, there’s more. Ben surprises the other students by bidding $10.01, rationally deciding it’s better to lose a penny than $9.99. Misha now faces the same dilemma, and so it goes on.

At some point, I call the auction off and, despite my teacher salary, tell them no one has to pay me. I ask Misha and Ben to describe how they felt, which almost always includes feelings of regret and being trapped. They were no longer bidding to win, but to minimize their loss.

This exercise is a great way to introduce students to the sunk cost fallacy. What’s that? It’s the spending trap that—once you start down a path by putting money into a venture—you feel compelled to see it all the way through, lest you’ve wasted the initial outlay. It’s “throwing good money after bad.”

Funnily enough, the British have an opposite expression, “In for a penny, in for a pound,” which means you show determination by sticking it out, no matter what. That can achieve great things, but it can also be a lot of wasted pennies—which could have gone toward buying an ale to celebrate losing only one penny.

The sunk cost trap is everywhere because we’re taught that successful people never give up, winners don’t quit, and the best solution is to never regret and never retreat, but instead always move forward. Unfortunately, this can also lead to prolonged failure, such as when decision-makers—who have invested financial, political and personal capital in a course of action—refuse to acknowledge that the time has come to cut bait and find another fishing pond (or try golf instead). A classic example: the Vietnam War.

Back in 2019, a seeming lifetime ago, my wife Jiab and I went to the beautiful seaside Spanish village of Almuñecar. Located on the Costa Tropical of Spain, it’s one of those movie-like places with white-washed houses with Moorish accents and long sandy beach buffeted by the azure-blue Mediterranean. We loved the place for ourselves, but also learned it was just starting to be discovered by tourists coming to Spain for vacation, especially from Scandinavia. We immediately decided to look into buying a place that we could use occasionally for our own getaways, but mainly to generate holiday rental income to supplement our retirement. We found a place close to the beach and, by early 2020, we had settled on a price and put down a deposit.

In Spain, there’s a quaint custom that real estate deals aren’t finalized until all parties meet with a notary, who reads the document aloud and signs off. This is left over from centuries ago when people were illiterate, so the notary ensured all parties understood what they were signing. Today, it’s a pro forma (and expensive) ritual that seals the deal.

Only we didn’t get to it.

COVID-19 hit and, as many remember, Spain went into total lockdown. All meetings were put off, so we sat in our home in Granada and waited to finalize the deal. And waited.

Of course, our first priority was to do our part to stop the spread of COVID, so we stuck it out at home. As the situation remained in stasis, and the news everyday foretold a “new normal” coming, Jiab and I started reconsidering the house purchase. For ourselves, there was no foreseeable time when we’d be allowed to go to the new place. Even more, no one was sure when—or even if—tourism would come back, so the prospect of the new place being a positive money-generator evaporated. There were even stories that groups were seeking out unoccupied homes and taking them over as squatters, often trashing the place.

On the other hand, we had already sunk a lot of money, time and effort into researching Spanish real estate, finding the place and negotiating a price. We had paid a lawyer both to translate for us and guide us through the process. We had a deposit that was partly nonrefundable.

We ended up letting the place go. We cancelled the deal from our Granada home, informing the seller that he could keep the nonrefundable portion of the deposit. We wired payment to our lawyer and then reluctantly accepted that we were out of pocket, with nothing to show for it.

Except we had escaped. We didn’t have to worry about squatters living in our rental property, or closely monitoring an inaccessible home, or fighting with others for the scraps of tourist dollars that were trickling in. We also realized how lucky we were, as we fretted about losing a second home, while many today are in fear of losing their primary one.

I suspect others are facing similar tough decisions, as COVID changes the entire financial lay of the land. It isn’t a bad idea to think about what ventures, investments and dreams we might be better off walking away from, or at least putting off for the moment, no matter how much we’ve already put in. Perhaps we should save what we still have, so we can spend it another day.

After all, $10 isn’t what it used to be.

Jim Wasserman is a former business litigation attorney who taught economics and humanities for 20 years. His previous articles include Choice Words, A Poisoned Chalice and Falling for Flattery. Jim is the author of Media, Marketing, and Me, about teaching behavioral economics and media literacy, as well as Summa, a children's story for multiracial, multi-ethnic and multicultural families. Jim lives in Spain with his wife and fellow HumbleDollar contributor, Jiab. Together, they write a blog on retirement, finance and living abroad at YourThirdLife.com.

Jim Wasserman is a former business litigation attorney who taught economics and humanities for 20 years. His previous articles include Choice Words, A Poisoned Chalice and Falling for Flattery. Jim is the author of Media, Marketing, and Me, about teaching behavioral economics and media literacy, as well as Summa, a children's story for multiracial, multi-ethnic and multicultural families. Jim lives in Spain with his wife and fellow HumbleDollar contributor, Jiab. Together, they write a blog on retirement, finance and living abroad at YourThirdLife.com.The post Sinking Feeling appeared first on HumbleDollar.

November 10, 2020

Slim Pickings

That loss, however, didn’t deter me. In my early days as a do-it-yourself investor, I mainly bought mutual funds, albeit too many of the high-fee actively managed variety. But I still had an interest in picking individual stocks.

In fact, it was part of my investing heritage. My father had always invested in individual stocks. In his day, mutual funds—much less index mutual funds and exchanged-traded index funds—weren’t yet “a thing.” And he had done well with individual stocks, so his success was likely in my thoughts.

I don’t know exactly how he picked his stocks, but some of it was probably based on the advice of stockbrokers. In addition, my dad was involved in business and civic affairs in our hometown of Dallas, and knew many of the people who ran some of the companies he invested in. If he thought that they were capable and of good character—character was paramount to my dad—he likely thought that was a good enough reason to invest in their company.

The upshot: In my early days, I wanted to put at least some of our modest investment money into individual stocks. But I’m not the public citizen my dad was and have no personal insights into how any company is run. I have virtually no education or work experience in finance or accounting. When I read a company’s annual report or SEC filings, frankly, it’s pretty much Greek to me.

So what’s a boy to do? Well, a smart one would’ve chucked the whole idea, bought some funds and been happy. But that would’ve been too easy, so I decided on a method of picking individual stocks that made sense to me. No, I wasn’t so foolish as to rely on tips from friends and family. I thought I had a more logical route.

What I would do is simply study the reputable financial magazines of the day—Forbes, Kiplinger’s, Barron’s and so on—and see which stocks the whizbang writers for those venerable publications were recommending. I would then do a sort of cross-reference. If I saw three or four different writers in three or four different publications recommend the same stock, bingo, I had a candidate. After all, if the movie experts and insiders at the Academy agree on some movies to nominate, chances are those are pretty good movies.

And in those days—the late 1990s—the recommendations were largely tech stocks, so I bought away. We all know how that turned out. The dot-com bubble burst in 2000 and I, along with a lot of others, got skinned.

I realized that my “cross-referencing the experts” method was a bust, and I lost as much or more than the typical investor. It was yet another painful lesson learned, but it paid off in the long run. I abandoned any hope of beating the market and, as so many wise men and women now advise, I was happy to simply own the market through index funds.

I still remember well that, of all those once-mighty tech companies that I read about and invested in, the one that was recommended by more experts than any other was a company called WorldCom. Its chief executive, Bernie Ebbers, was often described as a genius among geniuses. In the tech crash, WorldCom’s stock went from a peak of $64.50 to less than $1, before trading was halted. And what of Bernie Ebbers, the genius of geniuses? He was later sentenced to 25 years in federal prison for fraud and conspiracy.

Andrew Forsythe retired in 2017 after almost four decades of practicing criminal law, first as a prosecutor and then as a defense attorney. Along with his wonderful wife, kids and grandkids, he loves dogs and collecting pocketknives. His previous articles were The Path Not Taken and Saved by a Crash.

Andrew Forsythe retired in 2017 after almost four decades of practicing criminal law, first as a prosecutor and then as a defense attorney. Along with his wonderful wife, kids and grandkids, he loves dogs and collecting pocketknives. His previous articles were The Path Not Taken and Saved by a Crash.The post Slim Pickings appeared first on HumbleDollar.

November 9, 2020

A Simpler Life

The first account I dealt with was my 403(b). Fidelity Investments was handling the 403(b) plan for the University of North Carolina System, which is where I worked. But while Fidelity was the administrator, the plan included several Vanguard Group funds, to which I’d been contributing. This was where I had the majority of my retirement money.

To simplify our finances, I stopped contributing to the account in January 2014 and transferred the balance to a rollover IRA at Vanguard. Even though I was still employed, I was able to do this “in-service distribution” because I’d reached age 59½. The rollover removed Fidelity as the middleman and allowed me to access my money directly using Vanguard’s website. My wife and I already had other accounts at Vanguard.

Rolling over my 403(b) money required quite a bit of paperwork, but I got representatives from Fidelity and Vanguard to walk me through their forms. I paid $25 to have Fidelity send the check overnight to Vanguard. The alternative was a free but slow transfer, during which Fidelity would no doubt earn interest. An electronic transfer wasn’t an option. This seems to be standard procedure when withdrawing money from brokerage firms. They want one last bite before they hand over your money.

In addition to removing Fidelity as the middleman, moving my 403(b) money to Vanguard meant I could invest the U.S. stock portion in Vanguard’s Total Stock Market Index Fund. The fund wasn’t available through my 403(b) at Fidelity, which only offered a limited number of Vanguard funds. In my 403(b), I’d split money among Vanguard’s S&P 500, mid-cap and small-cap index funds in an effort to replicate the broad U.S. market.

I also had a small Roth 403(b) account at Fidelity, but I kept this in place until I retired, so I could continue contributing to it via payroll deduction. After retiring, I rolled this into a Roth IRA I already had at Vanguard.

In addition to my 403(b), I had money in a 457 plan with the State of North Carolina that was administered by Prudential. Even though the fund expenses are higher than Vanguard’s, I’ve left significant money in the account. Why? My 457 is covered by a North Carolina state law—since changed—that meant money could be withdrawn without paying state income tax. In fact, I’m able to roll money into the account and then withdraw it, thus avoiding state taxes—something I plan to do periodically.

My wife already had a rollover IRA at Vanguard that held money from a retirement plan she had with a former employer. On top of that, she had a SIMPLE IRA at Vanguard, which allowed her to make pretax contributions from her private practice earnings as a clinical social worker. When she retired, we moved this money into her rollover IRA.

The upshot: We started 2014 with seven accounts—a 457, 403(b), Roth 403(b), rollover IRA, SIMPLE IRA and two Roth IRAs—with these seven accounts spread across three financial companies. When the smoke cleared, we were down to five accounts—a 457, two rollover IRAs and two Roth IRAs—at two companies. I was also able to use the same Vanguard funds across all our accounts, except for the one bond fund I keep in the 457 plan at Prudential. All this greatly simplified our investments, making it much easier to track our portfolio and to rebalance occasionally.

Still, we may not be done with our simplifying. Eventually, when I get tired of managing our investments, I’ll just move all our money into a Vanguard target-date retirement fund or one of the firm’s target-risk LifeStrategy funds. These funds offer a diversified portfolio in a single mutual fund, with Vanguard handling all rebalancing. Why not make the move now? These one-stop shopping funds have slightly higher expenses than the funds we currently own and, for now, I’m having too much fun doing the rebalancing myself.

Brian White retired from the University of North Carolina, where he worked as a systems programmer and then director of information technology in the computer science department. His previous articles include Time to Retire, Limited Selection and Lesson Well Learned. Brian likes hiking with his wife in a nearby forest, dancing to rocking blues music, camping with friends and stamp collecting. He also enjoys doing Volunteer Income Tax Assistance (VITA) work at the Chapel Hill senior center.

Brian White retired from the University of North Carolina, where he worked as a systems programmer and then director of information technology in the computer science department. His previous articles include Time to Retire, Limited Selection and Lesson Well Learned. Brian likes hiking with his wife in a nearby forest, dancing to rocking blues music, camping with friends and stamp collecting. He also enjoys doing Volunteer Income Tax Assistance (VITA) work at the Chapel Hill senior center.The post A Simpler Life appeared first on HumbleDollar.

November 8, 2020

Sweat the Big Stuff

John Cleese, the English actor and comedian, is largely retired. But in an interview, he described his approach to getting work done. When he had a weekly TV show, Cleese said, he didn’t worry about being unproductive some days. “I learned... that no matter the distractions, over a week we’d get 15 to 18 minutes of sketches completed.”

How is this relevant to financial planning? I’ll answer with a brief story. Several years back, I was working with a young couple. A key goal was to purchase a home, and they wanted to know whether they were saving enough. They had good incomes but wondered whether their spending was too high. For example, they asked whether they were spending too much on organic fruit.

My response to the young couple: Instead of looking line by line at your spending, a much easier way is to look at your overall savings rate. Just ask whether you’re meeting your annual savings goal. If you are, it almost doesn’t matter how much you choose to spend on any one item.

You can see the parallel. John Cleese knew he had accomplished enough in a week if he had the 15 to 18 minutes of jokes he needed for his show. In saving for the future, it’s exactly the same. As long as you meet your annual savings goal, there’s very little else to worry about.

This approach, I find, helps cut through a lot of worry. Some families worry whether they can afford a vacation or a particular school’s tuition. Others fret about the mortgage on a new home. But with the John Cleese approach, it becomes much easier to answer any of these questions. Like Cleese, if you know you’re doing what you need to do on the savings side, you can do as you please on the spending side.

How is that savings rate calculated? There are six steps:

Step 1: Estimate your retirement date. For this example, let’s suppose you're age 40 and want to retire in 25 years.

Step 2: Determine how much you’ll need to withdraw from your portfolio each year in retirement. This step requires a few calculations, but it shouldn’t be difficult. Start with your current annual spending. Then subtract the expenses you don’t expect to have later in life. These might include childcare or school tuition. It might also include your mortgage, which ideally would be paid off by that time.

Next, be sure to increase this number to account for inflation, which might be 2% or 3% a year. You should also take into account Social Security and any other sources of income you expect in retirement. The net of these numbers will be the sum you would need to withdraw each year from your nest egg. Suppose you would need $100,000 a year, including money earmarked for taxes.

Step 3: Estimate your required nest egg. For simplicity, start with the 4% rule and use that to calculate how big a portfolio would be required to safely generate this $100,000 a year. If you divide $100,000 by 4%, that translates to $2.5 million. That’s the nest egg you would want to amass by the first day of retirement. (I should note that the 4% rule is hardly gospel, but it provides a useful ballpark figure.)

Step 4: Tally up the savings you’ve already accumulated. If you’re mid-career, let’s assume you have $300,000 saved.

Step 5: Calculate how much you’ll need to save each year. Let’s assume you expect to earn a 5% annual return. Enter that 5% plus the numbers above—25 years to retirement, $300,000 currently saved, $2.5 million needed at retirement—into a spreadsheet using this formula:

= PMT(5%, 25, -300000, 2500000)

If you plug that into Excel or Google Sheets, the answer you get will be about $31,000. That’s the amount you’d need to save each year to reach your retirement goal using the above assumptions.

If you run this calculation and the resulting figure appears dauntingly high, don't despair. You should view this figure as an average. If you're early in your career, you can start at a lower number and then increase it over time as your income grows.

Step 6: Stress test your results. You'll notice that each number I've used here was an estimate. They might be reasonable, but nonetheless they're estimates. For that reason, I recommend conducting stress tests. For instance, you try out a higher spending number or a lower estimated investment return.

This is useful for two reasons. First, you'll get a sense of the relative importance of each variable. As you experiment, you'll see that some matter much more than others. Second, while I recommend boiling your goal down to a single number for planning purposes, it’s important to first consider a range. For example, you might find that your plan will probably work with a savings rate of $30,000, but it will almost certainly work with savings of $40,000. Whether you choose to plan on the lower or the upper end of that range will depend on what's feasible given your budget today and your willingness to take risk. But it's important to start by knowing what those lower and upper bounds are.

To be sure, there are other considerations that go into financial planning. But as a framework for managing your financial life today to help you get where you want to go tomorrow, I can't think of a more useful way than the John Cleese way.

Adam M. Grossman’s previous articles include Emerging Concerns, Look Under the Hood and Follow the Fed. Adam is the founder of Mayport, a fixed-fee wealth management firm. In his series of free e-books, Adam advocates an evidence-based approach to personal finance. Follow Adam on Twitter @AdamMGrossman.

Adam M. Grossman’s previous articles include Emerging Concerns, Look Under the Hood and Follow the Fed. Adam is the founder of Mayport, a fixed-fee wealth management firm. In his series of free e-books, Adam advocates an evidence-based approach to personal finance. Follow Adam on Twitter @AdamMGrossman.The post Sweat the Big Stuff appeared first on HumbleDollar.

November 7, 2020

Future Shock

I find the insights below fascinating, in part because they describe how I behave with uncanny accuracy. Many readers, I suspect, will also catch a glimpse of their own behavior:

Moral licensing. If we do something good—exercise, give to charity, work late, purchase an eco-friendly product—we often give ourselves permission to do something that’s not so good, such as rewarding ourselves with junk food or a new pair of shoes. In fact, research has found that simply thinking about doing something good, even if we don’t follow through, can prompt not-so-good behavior.

This is certainly a mindset I have. If I’ve been careful about my eating all week, I feel I “deserve” something unhealthy. Two decades ago, when I regularly ran marathons and half-marathons, I’d typically do my long runs on Saturday morning—and spend much of the time pondering the Italian sub and fries I’d devour afterwards.

Willpower budget. As with moral licensing, this is another explanation for why we slip from the straight and narrow. The notion: If we’ve been disciplined all day—eating carefully, focused on work, going to the gym at lunchtime—we might reach the end of the day with our willpower budget depleted, leading us to have that extra glass of wine or an extra-large slice of pie.

Can we expand our willpower budget? It isn’t clear. But if we can take our desired good behavior and turn it into habits—perhaps we make it a point to always exercise on certain days, always have a salad for lunch and always max out our 401(k)—these things may come to require little or no willpower. Our good habits may not expand our willpower budget, but they could free up part of that budget for other areas where we’re trying to improve our behavior.

Even so, we'll occasionally find our self-discipline at a low ebb. If you’re like me, you have much more discipline early in the workweek—and far less come Friday, when pizza, a movie and a glass of wine prove irresistible.

Signaling. We’re constantly projecting an image of ourselves to others with the possessions we buy and the activities we engage in. A BMW sends one signal. A Prius says something quite different. The danger: We end up spending money in ways that send the desired signal, but aren't things we truly care about

I’ve become perhaps too aware of signaling. As I read emails and talk to others, I find myself paying careful attention to what’s said—and what self-image the person is trying to project. Some folks are more subtle than others, but we’re all doing it, consciously or not.

End-of-history illusion. As regular readers know, I just moved to Philadelphia. It was a big change—returning to city life, downsizing, buying a place where I hope to spend the rest of my life—and it seemed like the end of a turbulent time and the start of a new, more settled, more tranquil period.

When I mentioned such thoughts to my daughter, she laughed—and rightly so. I am suffering from what’s called end-of-history illusion. We look back and recognize all the upheaval in our life and how much we’ve changed, and yet we assume all the learning and growing is now over—and there will be far less change in future. And we are, of course, kidding ourselves: What we want from life will continue to evolve.

One implication: The consumption decisions we make today—the homes we buy, the furniture we purchase, the art we hang on the walls—may prompt a rueful shake of the head a few years down the road. If it’s a modest purchase, this probably doesn’t matter, because the flared jeans and combat boots will likely wear out before our tastes change.

But if it’s a purchase that’ll potentially be with us for years to come and that’s difficult to undo, we should probably think hard about our future self and how he or she will view today’s decision. We’re talking here about things like second homes, backyard swimming pools, boats, timeshares—and, of course, body piercings and tattoos.

Latest Articles

HERE ARE THE SIX other articles published by HumbleDollar this week:

Worried that your ability to handle your finances will slip as you grow older? Dennis Friedman offers eight pointers.

"There’s nothing showy about saving money," notes Jiab Wasserman. "We often celebrate a promotion or a business success, but we seldom celebrate when we’ve maxed out our 401(k) or reached a financial milestone."

Picking health insurance for 2021? Dick Quinn—who spent almost his entire career in employee benefits—offers some pointers.

"You can get any result you want by cherry-picking time periods," notes Bill Ehart. "But come of age at the wrong time and you might rue the day you read about Eugene Fama and Kenneth French."

Veteran money manager Jeremy Grantham says you should dump U.S. stocks and load up on emerging markets. A smart strategy? Adam Grossman has his doubts.

Who won the popular vote? Check out HumbleDollar's seven most widely read articles during October.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter @ClementsMoney and on Facebook. His most recent articles include Scary Stuff, Irksome Adversaries and Where We Stand.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter @ClementsMoney and on Facebook. His most recent articles include Scary Stuff, Irksome Adversaries and Where We Stand.The post Future Shock appeared first on HumbleDollar.

November 6, 2020

Try Not to Slip

My immediate thought: “How could my medical provider charge me for a flu shot that I haven’t yet received? And why aren’t they billing Medicare?” Medicare provides a free flu shot to every enrollee.

I called my doctor’s office to find out what was going on. I explained to the billing department that I had been erroneously charged $30.80. I told the representative that I don’t take medication and the only explanation for the charge had to be the flu shot that I hadn’t received yet.

The representative said that couldn’t possibly be true, because the office doesn’t bill my prescription drug plan. We went back and forth for a while, until he suggested that I call my drug plan to find out what the charge was for. I said, “I know it’s for the flu shot and I’ll be calling you back to get to the bottom of this.”

I grudgingly called my insurance plan. While a representative there had me on hold, I decided to look again at the email I’d received. As I glanced at the message, I noticed in blue letters the words: “Premium payment of $30.80.”

Yes, it was my mistake. I didn’t take the time to read the email carefully, and instead got emotional and jumped to conclusions. I usually don’t receive premium payment notifications from my prescription drug plan, but that didn’t excuse my behavior.

The next day, AT&T was coming to my house to service my wi-fi. I recently had my house remodeled and I believed the workers might have broken something during the renovation. I kept telling them that they needed to be more careful with our belongings.

When I reconnected the wi-fi, I couldn’t get access to the internet. I suspected the workers either damaged the modem or the wiring in my house. What else could it be? It was working perfectly before they showed up.

When the service repairman arrived, he bent down, looked at the modem and said, “Oh, I see your problem. You have the wires on the modem reversed. They’re connected to the wrong ports.”

Yes, it was my mistake. I didn’t pay close attention to what I was doing when I reconnected the modem. I was so sure it was someone else’s fault.

I like to think neither of those mistakes would have happened in earlier years. As I’ve grown older, I’ve become more impatient, emotional and overconfident in what I’m doing. I also sometimes don’t see the obvious.

Those are not attributes you want when managing money. According to a New York Times article, “Studies show that the ability to perform simple math problems, as well as handling financial matters, are typically one of the first set of skills to decline in diseases of the mind.” On top of that, many seniors—who appear to have the wherewithal cognitively—may no longer have the ability to fully understand financial matters, increasing the chances of financial mistakes.

The upshot: I'm not saying the two episodes I’ve described above indicate I can’t manage my money and need help. But they are warning signs that tell me I need to be more careful as I age. What should I and others do? Here are eight pointers for how the elderly can better manage and protect their money:

Look after your brain. Research has shown that having a healthy lifestyle has a positive effect on the life of the brain. Exercising, eating healthy foods and getting plenty of sleep can improve your cognitive skills.

Seek help. Hire a fee-only financial advisor to manage your investments. This could protect you from devastating financial mistakes. You might also seek advice from trusted family members on important money matters.

Simplify your finances. Invest in a target-date retirement fund or a few broad market index funds that require little maintenance.

Buy an annuity. You can protect part of your money from investment mistakes by purchasing an immediate fixed annuity. You make an upfront payment to an insurance company and, in return, you can receive monthly income for life.

Don’t use cash. Instead, use credit cards and checks, which will create a paper trail for all your major financial transactions.

Automate your finances. Many seniors have dexterity problems and poor eyesight that can make performing transactions difficult. Set up direct deposits, automatic transfers and automatic bill payments to help eliminate financial errors.

Draw up advanced directives. Have in place powers of attorney for your finances and health care. These will allow someone to oversee your affairs if you become incapacitated.

Guard against telephone scammers. How? Don’t answer the phone unless you recognize the number. Register your phone number with the National Do Not Call Registry. Use apps that block robocalls.

Dennis Friedman retired from Boeing Satellite Systems after a 30-year career in manufacturing. Born in Ohio, Dennis is a California transplant with a bachelor's degree in history and an MBA. A self-described "humble investor," he likes reading historical novels and about personal finance. His previous articles include Go Long, The Short Game and It Sure Adds Up. Follow Dennis on Twitter @DMFrie.

Dennis Friedman retired from Boeing Satellite Systems after a 30-year career in manufacturing. Born in Ohio, Dennis is a California transplant with a bachelor's degree in history and an MBA. A self-described "humble investor," he likes reading historical novels and about personal finance. His previous articles include Go Long, The Short Game and It Sure Adds Up. Follow Dennis on Twitter @DMFrie.The post Try Not to Slip appeared first on HumbleDollar.

November 5, 2020

Factored In?

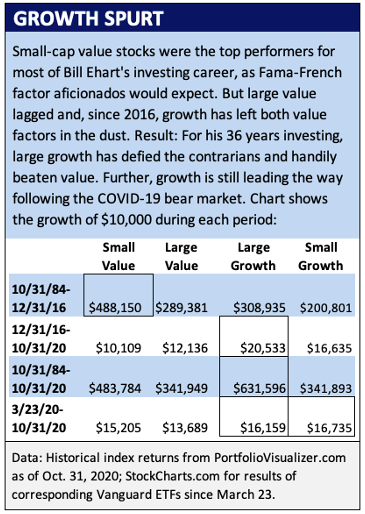

WELL, IT SOUNDED good. Academic theory and nearly a century of investment experience supported the argument that small-cap value is the most promising market segment over the long term, since it offers the superior risk-adjusted return that comes with owning both neglected small-cap shares and shunned value stocks.

But as legendary economist John Maynard Keynes observed, in the long run, we are all dead. In my 36-year investment career, both small- and large-cap value have lagged large-cap growth. Fortunately, I have 10 more working years left, and I haven’t given up on small, mundane companies.

You can get any result you want by cherry-picking time periods. But we don’t get to choose when we’re born. Come of age at the wrong time and you might rue the day you read about Eugene Fama and Kenneth French.

The two finance professors analyzed stock returns since 1926. They developed a “factor” model in 1992, providing the rationale for why small-cap value should perform best long term, followed by large value, large growth and small growth, in that order.

But how relevant is data from the mid-20th century? Further, small-cap outperformance can be isolated to a few relatively short periods, such as the mid-1970s to mid-1980s. From Dec. 31, 1974, through Oct. 31, 1984, small-cap value compounded at a 30.2% annual rate, compared with 22.8% for small-cap growth, 18.4% for large-cap value and 12.5% for large-cap growth, according to PortfolioVisualizer.com. Yet, before the 1980s, it would have been prohibitive to build a diversified portfolio of small-cap value stocks, as Ben Carlson noted recently in his excellent blog.

Our own investing lifetimes are what’s relevant to us. I graduated from college in 1984. Let’s say that, by Oct. 31 of that year, I was able to start investing in earnest and I bet on small-cap value. Meanwhile, my cousin Mike went for large growth companies.

Sure enough, through 2016, I would have looked like a genius, even though I got into small value after an historic run. As you can see in the accompanying chart, an initial investment of $10,000 on Oct. 31, 1984, would have been worth nearly $180,000 more than Mike’s large-cap growth stake.

The lousy performance of small growth companies from late 1984 through 2016 also seemed to validate the Fama-French model: They combine the riskiness of unproven companies with the inflated expectations of growth stocks. On the other hand, contrary to Fama-French, large value lagged large growth.

The lousy performance of small growth companies from late 1984 through 2016 also seemed to validate the Fama-French model: They combine the riskiness of unproven companies with the inflated expectations of growth stocks. On the other hand, contrary to Fama-French, large value lagged large growth.

But hypothetical me, gloating about my small-cap value victory, started picking out retirement homes in Boca too soon. That’s because small-cap value has been a disaster since 2016.

Over the whole period, from Oct. 31, 1984, to the present, Mike would be way, way ahead on his $10,000 initial investment. I would barely have any more money than in 2016, while Mike would have over $300,000 more than he had.

What does this prove? It shows that factor bets can be incredibly lucrative but also hazardous to our wealth. We have to avoid blind adherence to investment rationales just because they sound good. But having chosen to emphasize a factor, we should avoid giving up after a period of weakness.

In my real life, I’ve been in and out of small-cap value since the 1990s, which reflects poorly on me as an investor. But the superior return potential of small-cap value still makes intuitive sense to me. I hope to retire in 10 years. Obviously, that’s too short a period to bet heavily on any one asset class. But it’s not too short to wager modestly on a factor rebound or on reversion to the mean.

I’ve put a few more chips on small-cap value stocks, for myself and my family, since they plunged in March, as I mentioned here and here, and I added a little more in October. I have a good rationale for this (there’s that word again).

First of all, small value historically has rocked after a period of irrational exuberance for large growth, as it did in the 1970s after the Nifty Fifty craze and in 2000-02, as the dot-com bust unfolded. Today, the valuation gap of large growth over small value is again at an extreme, as O’Shaughnessy Asset Management and others have noted. Second, small-cap value tends to lead coming out of a bear market. That said, it hasn’t led since this year’s March 23 market bottom, as shown in the chart. (For what it’s worth, small-caps were positive in October while the overall market fell.)

Nearly 12% of my stock portfolio is in dedicated U.S. and foreign small-cap value funds. That’s a hefty satellite position, and my only factor bet. It’s enough to make a meaningful impact on my returns if undervalued small companies outperform again, but not so much to make me a complete fool if they don’t. Would I be greedy if I bet a bit more?

Maybe by the time I retire, small-cap value will be on top again, and all will be right with the world and the Fama-French model.

In which case, Mike will be welcome in Boca.

William Ehart is a journalist in the Washington, D.C., area.

Bill's previous articles include Shooting Stars, Different Strokes and Needing to Know

. In his spare time, he enjoys writing for beginning and intermediate investors on why they should invest and how simple it can be, despite all the financial noise. Follow Bill on Twitter

@BillEhart

.

William Ehart is a journalist in the Washington, D.C., area.

Bill's previous articles include Shooting Stars, Different Strokes and Needing to Know

. In his spare time, he enjoys writing for beginning and intermediate investors on why they should invest and how simple it can be, despite all the financial noise. Follow Bill on Twitter

@BillEhart

.

The post Factored In? appeared first on HumbleDollar.

November 4, 2020

Saving Happiness

But using only income to measure the link between money and happiness is incomplete. Another study, entitled “How Your Bank Balance Buys Happiness,” analyzed the connection to people’s “cash on hand.” The researchers found that having more money in checking and savings accounts was associated with higher levels of life satisfaction. But similar to the income studies, so-called liquid wealth appeared to be subject to diminishing returns, with the impact on life satisfaction tapering off as folks have more.

Which brings me to tennis. We recently moved from Granada, Spain, to Alicante, which is about 220 miles to the east and right on the Mediterranean. Alicante has milder weather that’s conducive to outdoor sports all year round, so most apartment complexes have tennis courts. My husband Jim accused me of looking for our new apartment based on the condition of the tennis courts first and the apartment second. Yes, I love playing tennis.

I also have a fondness for tennis analogies. I think saving money is like playing good tennis defense, while making more money is like playing offense. There are plenty of YouTube videos of the best winning shots, but relatively few that focus on the defensive skill that’s needed to keep the ball in play. Playing defense isn’t flashy. Yet Novak Djokovic, arguably the world’s top player, is renowned for his defensive play and for his ability to turn defense into offense.

Along the same lines, making more money, moving up the corporate ladder and building your own business are all exciting. People love to talk about such successes and to show off what this money has bought them, whether it’s the new car or the bigger house. But they never pull out their latest portfolio statement and say, “Look at my balance.” There’s nothing showy about saving money. We often celebrate a pay raise, a promotion or a business success, but we seldom celebrate when we’ve maxed out our 401(k) plan or reached a financial milestone.

In tennis, playing defense is mostly about limiting your mistakes, while waiting for the opportunity to strike. In football, it’s said that “defense wins championships.” Isn’t it the same in life? Progress—and ultimate success—are typically achieved through hundreds of smart, boring, stay-the-course decisions, rather than through flashy gambles.

Indeed, for most people, financial success is more about limiting mistakes and less about striking it big. Limiting mistakes means minimizing expenses by investing in index funds, living within your means, making the most of your 401(k) and so on. Like the turtle, it’s slow and steady that wins the race.

I have always been a saver. When I earned a bonus or got a raise, I saved the extra money. Even when I didn’t earn much, I still saved. I saved no matter what my circumstances were.

In an earlier article, I wrote about the importance of financial literacy for women. It’s one way for women to level what’s otherwise an unequal playing field. Similarly, I’d argue that saving money is even more important for women than men. A 2018 survey found that, for 65% of women, financial anxiety is the No. 1 source of stress, while the No. 1 thing that makes women feel in charge of their future is “putting away money for financial goals.”

No matter how hard I worked, I had limited control over the salary increases or bonuses awarded by my supervisors. But saving money and seeing my nest egg grow helped offset that, giving me a sense of control not only over my finances, but also over my life. It gave me confidence in my future—and that, in turn, bolstered my happiness.

Jiab Wasserman's previous articles include Riding It Out, Enforcing the Rule and When You're No. 2. Jiab and her husband Jim, who also writes for HumbleDollar, currently live in Alicante, Spain. They blog about downshifting, personal finance and other aspects of retirement—as well as about their experience relocating to another country—at YourThirdLife.com.

Jiab Wasserman's previous articles include Riding It Out, Enforcing the Rule and When You're No. 2. Jiab and her husband Jim, who also writes for HumbleDollar, currently live in Alicante, Spain. They blog about downshifting, personal finance and other aspects of retirement—as well as about their experience relocating to another country—at YourThirdLife.com.The post Saving Happiness appeared first on HumbleDollar.