Bill Treasurer's Blog, page 6

October 11, 2023

Mistakes and the Value of Risk

Nobody’s perfect, but that doesn’t seem to stop people from trying. And why not? There are lots of good reasons for wanting to be perfect. Some professions, for example, greatly benefit from their inherent perfectionism. This is especially true of professions where the consequences of a mistake would be catastrophic, where the human or the financial costs of errors are simply too great to bear. Indeed, the higher the potential for catastrophe, the more necessary and warranted is perfectionistic behavior. Consequently, among the most perfectionistic people you’ll ever meet are bridge-building engineers, skyscraper architects, nuclear physicists, software engineers, and brain surgeons. I, for one, thank God for that. If you ever had the misfortune of requiring brain surgery and had to choose between a pursed-lipped, anal-retentive surgical tactician or a giddy, free-wheeling improvisationalist, who would you choose?

Not so Perfect

The trouble with perfectionism is that it impedes our ability to take risks. Perfectionists are better suited for mitigating risks than for taking them. This mostly stems from their almost obsessive preoccupation with anticipating what can go wrong. Perfectionists are prone to “catastrophizing,” focusing on worst-case scenarios in order to account for, and control, every possible negative outcome. This, in turn, lends itself toward a doom-n-gloom outlook when facing a risk. Thus, risks themselves are seen through a prism of negativity that not only makes the risk-taking experience unenjoyable but through the power of expectancy often sets it up for failure as well.

Whether you have decided to pursue your risk, or if you have just jumped off your risk platform, you will have a more difficult time of it if you are a perfectionist. Risk-taking is inherently a mistake-driven process, characterized by a whole lot of trial and a whole lot of error. What perfectionists hate most are mistakes. To perfectionists, a mistake is more than an error; it is a failure that reflects on them personally. You can even hear it in their language. After making a mistake an average person will say something like “My idea didn’t work so I tried something else,” but a perfectionist will scornfully lament, “I tried my idea and it was an utter failure. I should have known it was a dumb idea. I won’t make that mistake again!”

Why Would You Risk Mistakes?When mistakes equate with failure, risk-taking is viewed as the surest path to dejection and humiliation. Thus the dispositions of perfectionists and risk-takers are often diametrically opposite. These differences are well captured by Dr. Monica Ramirez Basco in her insightful book on perfectionism, Never Good Enough. She explains that risk-takers are unlike perfectionists in that they “do not expect themselves to always be right or always have great ideas. But they know that if they keep trying, they will hit upon a winner. If their ideas are rejected, they might get their feelings hurt but they will recover quickly. The consequences of failure for these people do not feel as great as they would to the perfectionist.”

Risk-takers view mistakes as an inevitable part of the risk-taking experience. Unlike perfectionists, who categorically assume that perfection is both necessary and attainable, the risk-taker knows better. It is not that risk-takers want to make mistakes. Rather they see mistakes as valuable sources of data that will ultimately help them attain their goals.

When someone pointed out to Thomas Edison that in inventing the incandescent light bulb he had performed 10,000 failed experiments, he is purported to have replied, “I have not failed. I just found 10,000 ways that didn’t work.” Risk-takers hold the view that, though painful, mistakes are to be expected.

The post Mistakes and the Value of Risk appeared first on Giant Leap Consulting.

September 28, 2023

9 Leadership Touchstones

What inspired you to write 9 Leader Touchstones, and what impact are you hoping it will have on leaders? What’s the “ripple” you’re trying to create?

What inspired you to write 9 Leader Touchstones, and what impact are you hoping it will have on leaders? What’s the “ripple” you’re trying to create?In some form or fashion, I’ve been writing this book for the better part of a decade. Fueled by my own experiences in the workplace—inspired by the actions of leaders, suppressed by them, or by navigating the journey of leadership myself—the desire to share this message continued to grow. However, everything started to move into focus when I moved into leadership consulting, and I witnessed the struggles of well-intentioned leaders firsthand. Behavioral accountability flows from the leader, and that starts well before the bottom line improves. The philosophical underpinning of our leadership model is this—Leaders first look to themselves. I hope this book inspires leaders of people, regardless of their level in the organization, to introspectively examine their impact, not just on the bottom line but on the lives of the people they lead.

Which of the 9 leadership touchstones do leaders tend to struggle with the most?Behavioral accountability flows from the leader, and that starts well before the bottom line improves.

I want to take a detour from your question to provide context for my answer. My answer connects to how I’ve defined the Leader Touchstones. When developing the Leader-First® (LF) Leadership model, I opted for some definitions from fellow researchers and social scientists. As you know, I adopted your definition of Courage because no other more succinctly captures the challenges leaders face daily. However, some touchstone definitions intentionally deviate from what we’d consider widely accepted definitions. Each touchstone fuels the dynamic, enduring organizational system in different ways and has a specific purpose. How a leader cultivates, exhibits, and guides the development of the touchstones in others can limit or enhance their effectiveness in reinforcing healthy culture dimensions.

By providing that context, my answer will make more sense. From my observations of working with leaders and from analyzing the data from our Leader Touchstone Assessment, it’s clear that Resilience challenges leaders the most in the current state of work. The ability to overcome adversity is the standard definition of Resilience. However, when developing the model definition, I couldn’t get past the period at the end of the sentence. I kept remembering how many times I’d overcome adversity in my life and how utterly exhausted I felt by it all, simply because I’m the kind of person who can handle a great deal of stress.

Assessment, it’s clear that Resilience challenges leaders the most in the current state of work. The ability to overcome adversity is the standard definition of Resilience. However, when developing the model definition, I couldn’t get past the period at the end of the sentence. I kept remembering how many times I’d overcome adversity in my life and how utterly exhausted I felt by it all, simply because I’m the kind of person who can handle a great deal of stress.

The ability to overcome adversity is the standard definition of Resilience.

While overcoming adversity is necessary, it shouldn’t come at the expense of your health and well-being or worse. The dictionary definition of Resilience is a slippery slope. It leaves leaders open to overcoming adversity at work, no matter the personal cost. The LF Leadership definition of Resilience gives specific guidance to leaders about how they should cultivate this touchstone. Resilience is the capacity to overcome adversity through the systematic renewal of the body’s four energy wellsprings—physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual.

We are in the midst of a global human energy crisis. Unrelenting pressure to perform, fewer resources, and an irrational focus on time management make redefining Resilience for leaders a significant challenge. For decades, we’ve been brainwashed into thinking that working late hours and long days increases high performance. Unfortunately, research confirms that not taking focused time to renew energy can catastrophically impair performance and endanger a person’s health and long-term well-being.

When considering your own educational, career, and leadership journey, which of the 9 leadership touchstones have you had to work on the most?Based on how a person grows in Emotional Intelligence (EI), this is where I’ve done the most intentional work throughout my career. It’s a muscle that we must constantly work. I tell my students, “You never arrive in leadership—it’s a lifelong journey.” With EI, nothing could be more accurate. Most people think their work is done if they score high when they take an EI assessment. But EI ebbs and flows throughout your lifetime based on change. Because our brains are hardwired to resist change, each change introduces new triggers. In these moments, we must step back and do intentional work to understand these triggers. Once we do that, only then can we start converting the change into productive engagement.

I’ve experienced lots of change throughout my lifetime. When you grow up the way I have, you get good at quickly assessing and managing the effects of change. But it doesn’t mean I haven’t had to put in the hard work each and every time.

About the Author

About the AuthorMy friend Dr. Jes DeShields is a talented and accomplished consultant, team and leader coach, writer, and speaker. As a thought-leader, her leadership insights are valuable to all those who listen. Her most recent book captures those insights, thoughts, and showcases the journey to what she calls a Leader-First Leader. You can learn more about Dr. Jes DeShields book, 9 Leadership Touchstones here.

The post 9 Leadership Touchstones appeared first on Giant Leap Consulting.

September 20, 2023

The Courage to Act

Taking action can be incredibly challenging for a variety of reasons, and these challenges are often deeply rooted in human psychology and behavior. It also takes courage, and it’s safe to say you probably have some experience with courage. What we choose to act on is often determined by our goals, our passions, and our instincts to be proactive in situations of self-preservation. Your motivation to act might be different from one act to the next, but the type of courage you have might not be.

Think about a time when you had extraordinary courage. You might not have had the opportunity to demonstrate astonishing heroism, but that team you’ve led, that comfort zone you’ve stepped out of, and that trust you instilled in a future leader might be your version of extraordinary courage.

Let Your Courage Take You Into the Second Act

When you’ve made a choice to be courageous, how did that conversation with yourself go? It was probably an internal struggle that had you weighing your options and finding personal fulfillment in the desired outcome.

To build momentum – to advance as a leader – the choice you make to be courageous is the building block of your next act. With each act, you can become more familiar with what you had to do to get to that point. That foundation allows you to build transferable courage.

Much like a transferable skill that you work very hard to develop, you should work just as hard to build transferable courage.

Find SimilaritiesAs you encounter new hurdles in your career, draw on past experiences to find the way to best move forward. Instead of starting with a blank canvas, you ask yourself, “How did I approach this situation last time?” The best leaders compile a database of solutions and processes that serve as their own personal roadmap. It’s easy to look at those solutions and processes as something that’s black and white – almost concrete. However, what you might not realize is there’s plenty of room for courage in that database.

Your professional career as a leader will put you in many different situations, but you can always find similarities in the way you act. More than likely you’ve made mistakes and even more so, you’ll make many more. You don’t have all of the answers or an instruction manual on hand for every position you might find yourself in, but you can still find similarities.

That doesn’t mean you have to break down each previous action to find out what you might already know. Drawing similarities means knowing what you already know, and being a leader means knowing that you have acted courageously in the past.

It Comes Down to Experience

Without stepping out of your comfort zone and being courageous, your experience stops before you ever start your first act. It’s those first valuable steps that show you that you can act – they show you that you have what it takes to be courageous.

As your experience builds as a leader or a future leader, you have an edge over the next obstacle or hurdle you might come across. You can’t navigate and traverse the ever-changing landscape of your career without experience. A lot like that landscape, you will have peaks and valleys – landmarks in your career that you will have to bridge and find a way to cross. Your experience lets you fill in those gaps and helps you stand courageously on those peaks.

Curtain Call

There’s not much that’s more personally fulfilling than sitting back and admiring your work. At the end of the day you can say “Hey, I did that. I was successful. I know I can do it again – maybe even better.” That is your transferable courage. When you can sit back after your act and admire your achievements you realize you can carry that effort and courage into the next act.

Now, I challenge you with a question: What is your next act, and how will you draw upon courage to face it head-on?

Photo by

The post The Courage to Act appeared first on Giant Leap Consulting.

September 13, 2023

The Open Door

The term “open door” is often considered a policy. But I think about it a bit differently. While leadership is often defined as a set of behaviors by which one person influences others toward the achievement of goals, it is really about providing growth, enrichment, and opportunity. Put more simply, leadership is about momentum and results. While these definitions are true, they somehow fall short. What mechanism should a leader use, for example, to “influence” strong performance? Has leadership evolved beyond carrots and sticks? And what about the people being led? Besides a paycheck, what do they get out of getting results for the leader? What’s in it for them? After all, the leader’s success depends on them, right? What’s missing is opportunity.

In exchange for advancing the leader’s goals, the people being led should expect work opportunities that provide:

Growth and personal developmentCareer fulfillment and enrichmentAcquisition of new skillsFinancial gain and other rewardsGreater access to leadership rolesWork OpportunitiesPeople and organizations grow and develop to the extent that they capitalize on opportunities to do so. Opportunities are important to leaders because they’re important to the people they lead. Opportunities are the venues where people can try, test, better, and even find themselves. The leader’s job is to match the opportunity to the person and to help the person—and the organization—exploit that opportunity for all it’s worth. Open-door leadership is about noticing, identifying, and creating opportunities for those being led.

Think for a moment about a leader you greatly admire. Pick someone who has led you, rather than someone on the world stage. What do you admire about him or her? Did he open a door to an opportunity where you could grow your skills or improve yourself, such as asking you to lead a high-profile project? How did she help illuminate a blind spot by giving you candid feedback that caused you to see yourself in a different and more honest way? Did he build your confidence by asking for your perspective, input, and ideas? Or did she openly advocate for your promotion, showing you how much she valued you? What doors did he open for you?

My bet is that the leaders you most admire are the ones who left you better off than they found you by creating opportunities that helped you grow. How?

By being open to you, valuing your input and perspectiveBy being open with you, telling you the truth even if the truth is difficult to hearBy helping you be receptive to new possibilities and experiences and new ways of perceiving and thinking.Open-door leadership involves creating or assigning opportunities in order to promote growth. By promoting the growth of those they lead, leaders increase the likelihood of their own success and advancement. They also increase the likelihood of creating other leaders, which is essential to building a lasting leadership legacy. Leaders create leaders by opening doors of opportunity that have a positive and lasting impact on the behavior of those they lead.

What Open Door Leadership is notTo be clear, open-door leadership is not about having an open-door policy. Such policies are just more management hokum. One of the surest signs of a rookie leader is the claim, “I have an open-door policy, and my door is always open so my employees can get to me.” Allowing yourself to be continuously interrupted is a recipe for lousy leadership. If your door is always open, how on earth can you get any work done on behalf of the people who are interrupting you? Open-door leadership is not about having a policy of keeping your door open to others. It’s about taking action to open doors for others. It is about so much more than giving people unfettered access to you.

As a leader, it is important to have a clear understanding of what your role is. How are you facilitating growth? Are you leaving those you lead better than you found them? Transform your idea of the open door from a policy to how you lead.

How are you opening doors for your team?

This post is based on an excerpt from Leaders Open Doors.

The post The Open Door appeared first on Giant Leap Consulting.

August 23, 2023

Internal Struggles and The Two Wolves

The internal struggles we face have a direct impact on our leadership. Being a good leader of others means first being a good leader of yourself. By not controlling our emotions, we subject those who look to us for guidance to toxic behavior. The first step in developing good leadership begins with addressing our internal struggles and mastering the two wolves inside.

Leadership and Internal StrugglesIt’s tempting to wag a finger at bad leaders and indict them for their character defects. There’s a feeling of relief in venting our anger at the misdeeds of people who so clearly assumed they were better than us. Sometimes our venting is justified. But sometimes focusing on “them” is just a cheap way to keep from focusing on ourselves. We, after all, are them.

The point of learning about the killer inside isn’t to make you better at prosecuting leaders you deem to be flawed. It is to understand how your leadership might be subject to hubris’s influence and control so that you can prevent being subsumed by it. Everyone is susceptible to selfishness. It’s counterproductive to expect your leaders, or yourself, to be vice free. Quite the opposite.

Identifying, understanding, embracing, and mitigating your imperfections and vices will strengthen your leadership impact and help you lead more effectively and virtuously. There’s a little Killer in all of us, and when you get familiar with how yours might be operating, it will have less control over you.

A Tale of Two WolvesSome of you may remember the old Cherokee legend about the two wolves. It’s one of those folklore stories that gets embellished with each retelling, including our version. As the story goes, an old Cherokee elder is teaching his grandson about the nature of being human.

He says, “Grandson, there is a great war going on inside of me. There are two wolves fighting inside my soul. One aims to please himself. He is shrewd, manipulative, and dishonest, and will climb over even his friends to get what he wants. He is thirsty for power and toxically ambitious and assumes the worst in others and is quick to lash out in anger. His aim is to conquer, dominate, and control. He is a hungry, bad wolf that can’t be trusted.”

Unless you have mastery over the totality of your own nature, you will be prone to causing a lot of leadership damage.

As his grandson listens intently, the elder continues, “The other wolf has a strong sense of justice and strives to do what is right and good. He is obedient in his service to others and is disciplined, and has mastery over his emotions, urges, and temptations. This wolf brings out the best in me and others. He is a generous and good wolf, worthy of trust.” The grandfather continues, “Grandson, this war is not just going on inside of me, but in the hearts of everyone.”

Then, punctuating the point, he adds, “Including your own.” The grandson, recognizing the truth of the story in himself, and eager to know the story’s outcome, questions, “Grandfather, which wolf will win the war?” Raising his hands, simultaneously pointing to his grandson’s heart and head, the grandfather replies, “The one you feed.”

What a wonderful story, right? It’s the universal story of what it means to be a human being.

Understanding Our WolvesLike the grandson, each of us can recognize those two wolves. Each of us has acted with virtue, nobility, and goodness. Yet each of us has acted selfishly, dishonestly, and immorally on occasion too. We are made up of those two wolves. Our conscience and innate sense of right and wrong help us recognize the two wolves who live in our souls. Russian novelist and Nobel Prize winner Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was right when he said, “The line separating good and evil passes not through states, nor through classes, nor between political parties either – but

Contending with the dualistic nature of your own character is a central and ongoing responsibility of every leader. Unless you have mastery over the totality of your own nature, you will be prone to causing a lot of leadership damage. Gaining self-mastery over one’s passions, urges, and temptations is what makes leading so challenging. This is true partly because self-mastery means going against the more craven parts of your human nature, particularly when you are emboldened with, or seduced by, leadership power.

Being a good leader of others means first being a good leader of yourself.

Being a good leader of others means first being a good leader of yourself. And that requires being a good caretaker for the two wolves, by giving them guidance, expression, and space. The bad wolf isn’t bad if given an outlet for expression. If you enjoy fighting with people, take a jujitsu class before work each day instead of arguing with your teammates at work. Leading yourself means knowing when and how to feed both wolves.

This post is based on an excerpt from The Leadership Killer: Reclaiming Humility in an Age of Arrogance.

The post Internal Struggles and The Two Wolves appeared first on Giant Leap Consulting.

August 16, 2023

A Leader You Can’t Trust

Let’s start with the obvious: if you don’t have the trust of the people you’re leading, you will fail as a leader. Without trust, people can’t put stock in your vision, won’t commit themselves to your directives, and will lose confidence in you. If people can’t trust you, they won’t be loyal to you either. All of this, of course, damages a leader’s effectiveness. With anemic levels of trust, you get weak results – and getting results is what you were charged with doing when you were put into a leadership role. Your longevity as a leader is directly tied to getting more wins than losses. In harsh terms, without trust, you’ll be a loser.

Given these trust realities, it’s head-scratching that some leaders still make leadership all about themselves and not the people they’re privileged to lead. They violate the first law of leadership: Leadership is not about you, it’s about serving the people you’re leading. You can’t afford to be a leader who can’t be trusted.

What a Leader Looks LikeOver the course of the last three decades, I’ve interacted with thousands of leaders across the globe. They’ve taught me a lot about what leaders do to build trust, and what they do that destroys it. Many of the lessons they’ve taught me are included in my newest book, Leadership Two Words at a Time: Simple Truths for Leading Complicated People.

Here’s what a leader you can’t trust looks like:

Always trusts his or her instincts above everyone else’s ideas,tasks people with busy work just to get every ounce of a workday out of them,never admit mistakes, believing that doing so makes you look weak,punishes even innocent mistakes harshly,throws the team under the bus when performance wanes, making it the team’s fault,shades the truth in their favor, sometimes stating boldfaced lies to get their way,rarely smiles or show human warmth,has a giant ego, using the word “I” way more than the word “we.”How about you? Do you have the trust of the people you are leading? How do you know? Here are some things you can do to be a leader who is worthy of people’s trust:

listen with genuine interest to people’s interests and concerns,set goals with people, versus unilaterally setting them yourself,take people’s suggestions and go along with ideas that are not your own,express gratitude sincerely and generously,ask for people’s input when making consequential decisions that impact their work,openly share some of your non-work identity, let them see what you look like outside of your leadership role,ask people for improvement feedback, and create an environment where people feel safe to give it,handle mistakes as valuable learning and coaching opportunities,spend more time with your team than with your bosses,provide air cover for your team, be their most loyal champion,always tell the truth, even when the truth will sting,say “we” way more than “I.”Leaders that LastThe good news is that loser leaders don’t last. A leader who can’t be trusted is one who can’t stay in a leadership role. There is a natural order to behaviors. Bad behavior yields bad outcomes, eventually. Thankfully it works in reverse too. Good behavior yields good results. Being a leader who can be trusted is the best way to gain the trust of the people you’re leading.

Bill Treasurer is the founder of Giant Leap Consulting, Inc., a courage-building consulting firm. He is the author of numerous bestselling books, including his newest book, Leadership Two Words at a Time. For the last three decades Bill and his team have worked with leaders from such renowned organizations as NASA, Saks Fifth Avenue, Aeroflow, Southern Company, Walsh Construction, Aldridge Electric Inc., the National Science Foundation, the Social Security Administration, and the US Department of Veterans Affairs. Learn more at CourageBuilding.com.

Photo credits: Leadership. by gstockstudio

The post A Leader You Can’t Trust appeared first on Giant Leap Consulting.

July 19, 2023

The Courage to Leap – Out of the Comfort Zone

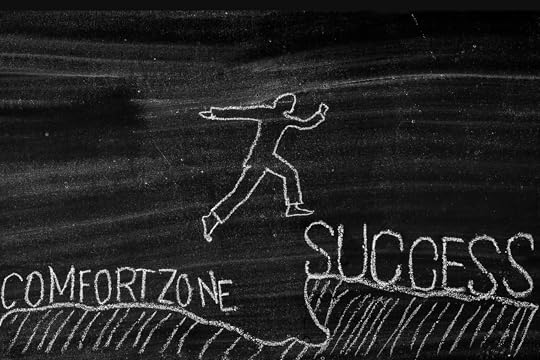

It takes courage to take a leap. Whether it’s a physical leap or stepping out of your comfort zone, everybody’s leap means something different to them, but the need for courage remains the same. The ability to become comfortable in an uncomfortable situation will help when taking a giant leap into the unknown.

Dustin Webster was scared; that much was clear. It was unusual to see him this way. Dustin is the kind of employee that a supervisor dreams of. A real go-getter, Dustin always got to work on time (often early), undeterred by the Seattle traffic and unfazed by Seattle’s soggy mariner weather. With Dustin, such things never prompted grousing or pessimism. He had more important things on his mind, like pitching in, helping out, and getting the job done. So seeing Dustin scared, really scared, was way out of the norm. Looking back on it now, I’m sure Dustin’s fear had something to do with the nature of the task.

Stepping Out of The Comfort ZoneFor Dustin, this was a pioneering endeavor. While he had plenty of skills to draw upon, and he had confronted plenty of other work challenges, this assignment went well beyond Dustin’s comfort zone and into foreign terrain. Firsts often provoke fear. I’m sure that Dustin had felt the same fearful feelings on his first day of school, the first time he drove a car, or the first time he kissed a girl. To see feelings were also at work the first time he led one of our team meetings, or the time I tapped him to be in charge when I got called out of town to temporarily lead another project. Because I was Dustin’s manager, my job was to help him temper his fear so that he could focus on the task at hand.

I had to believe in Dustin’s potential more than he believed in it himself.

I had to keep his potential at the forefront of my thinking. In a real way, I had to believe in Dustin’s potential more than he believed in it himself. Yes, Dustin was scared, and he had a right to be. In a moment, he would attempt a triple-twisting back double somersault after leaping backward from a tiny platform more than one hundred feet above the surface of a small pool. He’d be traveling at a velocity of over fifty miles per hour, a breakneck speed that could quite literally break his neck. Surprisingly, the things Dustin did to prepare for his big leap, and the things I did to coach him through it, were a little different from the things workers and managers need to do to help them stop being comfortable.

Becoming ComfortableThe big leap that Dustin was facing was a huge feat, but it wasn’t entirely outside the realm of his experience. The dive was just the next logical step in the progression of his skills and capabilities, and the culmination of lead-ups—less complex dives from lower heights—that he had taken over time. Plus, we had spent weeks preparing for this moment, building his confidence in a way that, metaphorically, lowered his high dive. Dustin first practiced doing takeoffs from the pool deck. Then we had him adjust the movable high-dive platform (called a perch) to ten feet above the water. Once he got comfortable with his takeoff from that height, we had him move it up twenty more feet. The process involved purposely moving from comfort to discomfort and back again.

When employees face challenges confidently and courageously, a positive outcome is more likely than if they don’t.

Once he got comfortable with one height, we’d stretch the height to a point of discomfort until the new height became comfortable, too. Each time Dustin got comfortable again, it was time for him to move up . . . we both knew the dangers of his becoming too comfortable! My job in all of this was to be Dustin’s chief encourager—literally, to help put courage in him. That meant I had to keep both of us focused on what Dustin had already done and what he was capable of doing. It would have done no good for me to stand on the pool deck yelling up to him about all the things he shouldn’t do. Yelling “Don’t do this!” and “Don’t do that!” would have kept him looking in the wrong direction. Instead, my coaching centered on the things he should do to make the dive happen.

Every High Dive Takes CouragePutting a worker in charge of your team while you go on maternity leave is a high dive. Informing a worker that you are considering her as one of three people for your successor is a high dive. One person’s triple-twisting back double somersault is another’s must-win sale, do-or-die project, or failure-is-not-an-option strategic initiative. High dives come in many forms, including skill-stretching jobs, big consequential assignments, and sweeping organizational changes. In each case, when employees face such challenges confidently and courageously, a positive outcome is more likely than if they don’t. In each case, a positive outcome is mutually beneficial to them, to you, and to the company. And in each case, the best way to get them to do their high dive is to get them to move beyond comfort and fear.

Whatever your high dive is, it’s important to know how to be successful. Your high dive might pale in comparison to Dustin’s, but that doesn’t make it any less important. Stepping out of your comfort zone, becoming uncomfortable, and finding the courage to take a leap can make your high dive successful.

The post The Courage to Leap – Out of the Comfort Zone appeared first on Giant Leap Consulting.

The Courage to Leap: Out of the Comfort Zone

It takes courage to take a leap. Whether it’s a physical leap or stepping out of your comfort zone, everybody’s leap means something different to them, but the need for courage remains the same. The ability to become comfortable in an uncomfortable situation will help when taking a giant leap into the unknown.

Dustin Webster was scared; that much was clear. It was unusual to see him this way. Dustin is the kind of employee that a supervisor dreams of. A real go-getter, Dustin always got to work on time (often early), undeterred by the Seattle traffic and unfazed by Seattle’s soggy mariner weather. With Dustin, such things never prompted grousing or pessimism. He had more important things on his mind, like pitching in, helping out, and getting the job done. So seeing Dustin scared, really scared, was way out of the norm. Looking back on it now, I’m sure Dustin’s fear had something to do with the nature of the task.

Stepping Out of The Comfort ZoneFor Dustin, this was a pioneering endeavor. While he had plenty of skills to draw upon, and he had confronted plenty of other work challenges, this assignment went well beyond Dustin’s comfort zone and into foreign terrain. Firsts often provoke fear. I’m sure that Dustin had felt the same fearful feelings on his first day of school, the first time he drove a car, or the first time he kissed a girl. To see feelings were also at work the first time he led one of our team meetings, or the time I tapped him to be in charge when I got called out of town to temporarily lead another project. Because I was Dustin’s manager, my job was to help him temper his fear so that he could focus on the task at hand.

I had to believe in Dustin’s potential more than he believed in it himself.

I had to keep his potential at the forefront of my thinking. In a real way, I had to believe in Dustin’s potential more than he believed in it himself. Yes, Dustin was scared, and he had a right to be. In a moment, he would attempt a triple-twisting back double somersault after leaping backward from a tiny platform more than one hundred feet above the surface of a small pool. He’d be traveling at a velocity of over fifty miles per hour, a breakneck speed that could quite literally break his neck. Surprisingly, the things Dustin did to prepare for his big leap, and the things I did to coach him through it, were a little different from the things workers and managers need to do to help them stop being comfortable.

Becoming ComfortableThe big leap that Dustin was facing was a huge feat, but it wasn’t entirely outside the realm of his experience. The dive was just the next logical step in the progression of his skills and capabilities, and the culmination of lead-ups—less complex dives from lower heights—that he had taken over time. Plus, we had spent weeks preparing for this moment, building his confidence in a way that, metaphorically, lowered his high dive. Dustin first practiced doing takeoffs from the pool deck. Then we had him adjust the movable high-dive platform (called a perch) to ten feet above the water. Once he got comfortable with his takeoff from that height, we had him move it up twenty more feet. The process involved purposely moving from comfort to discomfort and back again.

When employees face challenges confidently and courageously, a positive outcome is more likely than if they don’t.

Once he got comfortable with one height, we’d stretch the height to a point of discomfort until the new height became comfortable, too. Each time Dustin got comfortable again, it was time for him to move up . . . we both knew the dangers of his becoming too comfortable! My job in all of this was to be Dustin’s chief encourager—literally, to help put courage in him. That meant I had to keep both of us focused on what Dustin had already done and what he was capable of doing. It would have done no good for me to stand on the pool deck yelling up to him about all the things he shouldn’t do. Yelling “Don’t do this!” and “Don’t do that!” would have kept him looking in the wrong direction. Instead, my coaching centered on the things he should do to make the dive happen.

Every High Dive Takes CouragePutting a worker in charge of your team while you go on maternity leave is a high dive. Informing a worker that you are considering her as one of three people for your successor is a high dive. One person’s triple-twisting back double somersault is another’s must-win sale, do-or-die project, or failure-is-not-an-option strategic initiative. High dives come in many forms, including skill-stretching jobs, big consequential assignments, and sweeping organizational changes. In each case, when employees face such challenges confidently and courageously, a positive outcome is more likely than if they don’t. In each case, a positive outcome is mutually beneficial to them, to you, and to the company. And in each case, the best way to get them to do their high dive is to get them to move beyond comfort and fear.

Whatever your high dive is, it’s important to know how to be successful. Your high dive might pale in comparison to Dustin’s, but that doesn’t make it any less important. Stepping out of your comfort zone, becoming uncomfortable, and finding the courage to take a leap can make your high dive successful.

The post The Courage to Leap: Out of the Comfort Zone appeared first on Giant Leap Consulting.

July 12, 2023

Knowing Yourself and Leading Others

A good leader knows who they are. They understand their fears, they’re courageous, and they can relate to others. Occasionally, emotions get in the way of sound judgment. It’s how we handle and respond to our emotions that allows us to be the best leaders we can be. We are flawed, but it’s those flaws; the “bad”, that allow us to understand others and become stronger leaders. When you are self-aware as a leader you have the opportunity to look at a situation subjectively. It’s through this step that we’re able to become stronger, more aware, and effective at leading others.

Self-KnowledgeThe starting point of leadership is self-knowledge. You’ve got to be intimately familiar with your inner workings. You need to know what makes you tick, and what ticks you off. You’ve got to know your values, interests, talents, and triggers. You need to be clear about what you can do well, and what you’ll do well to have others do. You’ve got to know what energizes and de-energizes you, and what you’re drawn to and repelled by. You’ve got to know you. Really well.

Having run a courage-building consulting company for two decades, I’m now convinced that the single greatest courageous action that any human being can take is the journey to the center of one’s self. This journey of self-discovery takes bravely facing, and accepting, various truths about yourself. It means coming to terms with all the facets of your very human nature, good and bad.

Each person, including every leader, is a pair of opposites. Knowing Thyself will teach you that you are likely caring, passionate, smart, disciplined, generous, and good. You are also likely occasionally judgy, uptight, petty, selfish, and less-than-good. In other words, you’re human! Just like every other leader who has ever lived.

The Good and the “Bad”Depending on the situation, mood, or even sheer randomness, you may be happy or glum, content or anxious, trusting or suspicious, confident or unsure, generous or piggish. None of those characteristics needs to be rooted out. There’s no need to reject the “bad” elements of yourself, because what constitutes “bad” is always shifting. All your emotions can be absolutely appropriate given the right context, and vice versa. There are plenty of work instances where impatience, skepticism, hesitancy, and even fright or anger is the right emotional response and plenty where such emotions will do damage.

One’s thoughts precede and, more importantly, dictate one’s actions. Knowing what’s going on in your inner world and being able to gently tame your thoughts and emotions will keep wild mood swings from impacting your outer world. A lot of wreckage has been left in the wake of leaders who let their emotions get the best of them. Left uncontrolled, anger, resentment, jealousy and envy, revenge, and lust are potent poisons, and nearly always the causes of failed leadership.

What fear might be behind this?

That doesn’t mean you have to be emotionally neutered – you are human after all – but it does mean you have to be mindful of the effects your inner self is having on the people you outwardly lead. Be astute to the fact that your personhood will have an impact on the reactions and results you will receive. The ability to observe our own thoughts and feelings, and alter them when they are undermining us, differentiates us from wild beasts.

Don’t Let Fear LeadAs a new leader, you have one key self-reflective question you should ask yourself anytime you feel angry, frustrated, anxious, or emotionally charged: What fear might be behind this? Very often, the reason you’re so upset is that you’re fearful that you will lose something, or not get something you feel you deserved. As a leader, you will learn that your fear, wherever it comes from, will be your biggest enemy and inhibitor. Nothing will twist your actions, decisions, and attitude as much as being afraid that you’re not going to get the [fill-in-the-blank: recognition, compensation, acknowledgment, admiration, respect] that you think you deserve. The journey to the center of yourself takes courage because it involves confronting your fears.

Knowing Yourself and Leading OthersThe value of self-discovery is that it helps you take personal inventory of everything that makes you you. Knowing yourself will also help you better understand those around you. While your values, thoughts, and emotions are uniquely your own, they are also universally felt. They will help you relate to the people you’re leading. As you advance as a leader, in influence, power, and stature, people will want to know that, at the core human level, you haven’t forgotten that you are just like them.

They need to know that when they are upset, overwhelmed, or feeling insecure. You should know where they’re coming from because you know what it’s like to feel those feelings. They understand that you may operate at a higher rung on the organizational ladder, but they want to know that you get where they are coming from, that you are made of the same gooey human source material, and that you have had, and can relate to, their hopes and hurts.

People’s insides always affect their outsides.

When you’re in a leadership role, it’s vital to have a clear understanding of human nature. You will spend the bulk of your time dealing with human beings and all their fickle insecurities and eccentricities. Self-awareness is a key differentiator between successful and unsuccessful leaders. People’s insides always affect their outsides. Knowing how people’s emotions impact their morale, well-being, and performance is a first-order responsibility.

After taking a personal inventory of your own emotional disposition and understanding how your emotions impact others, you will be much less perplexed when you see human idiosyncrasies interfere with people’s work performance and productivity–as they often will.

This post is based on an excerpt from Leadership Two Words at a Time: Simple Truths for Leading Complicated People.

The post Knowing Yourself and Leading Others appeared first on Giant Leap Consulting.

June 21, 2023

Taking the Right Risk as a Leader

Choosing to take a risk is often well-calculated. You understand the consequences. You know what you have to gain and what you have to lose. At one point or another, you’ve likely had to make a decision that exposed you to great risk. Do you take the risk and if so was it the right risk?

Before I became an organizational development professional, I was a professional high diver with the U.S. High Diving Team. Every day for seven years, I climbed to the top of a hundred-foot ladder, stood atop a one-foot-by-one-foot perch, and hurled myself off — plummeting 10 stories down at speeds of more than fifty miles per hour into a pool that was only ten feet deep.

Making the JumpMost high divers perform their first high dive during practice. I, however, had decided to perform my maiden high dive during our show in front of a live audience of 2,000 Texans. I had been inching toward this moment for weeks. High divers do not start at the top, they start at the bottom. Each day during practice, my teammates and I would goad each other leaping from incrementally higher heights—first 10 feet, then 20, and so on.

My moment had arrived. Under the sweltering Texas sun, I grabbed the steel of the high-dive ladder. The higher I climbed, the more nervous I became. The body has a way of resisting foolishness. My palms tingled with sweat. My stomach teemed with rioting butterflies. I could hear the thumping of my pulse. Although I had performed scores of dives at lower levels, this was feeling more and more like an unnatural act.

The Right ReasonAt 60 feet I made a major mistake—I looked down. Suddenly, I was struck with paralyzing fear. “Oh God,” I groaned, “this is the stupidest thing I’ve ever done. I should turn back now while I can still get out of this alive.” The absurdity of the moment was head-spinning. What was I trying to prove? Was I really doing this to conquer my secret fear, or was it something else?

After a few deep breaths, I started to regain my composure. Somewhere inside me, a little voice reasoned,

“You can do this. You’ve visualized this moment over and over, you’ve practiced long and hard, and you’ve got a lot of support down there on the pool deck. Press on.”

With that, I swallowed hard, looked up at the top platform, and followed the assurances of my inner voice.

My back was to the audience as I situated myself on the top platform. To heighten the dramatic impact, a diver does not turn to face an audience until they are on the edge of their seats. As our team captain would say, “We want ‘em frog tight with anticipation.” This interlude of theatrical suspense allowed me to catch my breath and view the expansive Texas horizon. It was stunningly beautiful.

The RiskA flurry of thoughts and feelings bombarded me.

“I could die. I could be dead in a few moments. Or maybe I will crash hard and be paralyzed. I’ll be in a wheelchair for the rest of my life.”

The fear was gripping, yet strangely exciting. This was, by far, the greatest risk I had ever attempted. It was a sheer rush teetering at the far edge of my own potential. It was also humbling. Of all the people who have ever lived, some 100 billion of them, there were probably fewer than 1,000 who had done what I was about to do. In a few moments, I would be one of them—dead, paralyzed, or otherwise.

As I stretched out my arms and readied for the dive, it was as if my body had become the fulcrum between the poles of fear and desire: fear of what could go wrong and desire to succeed. It was an odd, balanced moment, a moment perfectly situated between past and future, surrender and pursuit. It was a NOW moment. Confronting my own mortality made me feel wonderfully alive and fully immersed in the present. I was filled with supersensory awareness, I could see for miles and miles, and I could feel the wind blowing between my fingers. And just above my head, on the top of the high-dive ladder, I could hear the American flag proudly snapping in the Texas wind.

Then the little voice whispered again, “You can do this.” With that, I jumped off the ladder as if I were leaping into the arms of God.

The RewardFor a fraction of a second—the instant between the dive’s pinnacle and descent—I was suspended in mid-flight like a swan hovering near heaven’s ceiling. Then, schwoosh, I started plummeting toward the water at breakneck speed. I had an overwhelming sensation that at any moment I would tumble out of control like a wayward lunar module. It looked as if the water was racing toward me with accelerating velocity, though the reverse was true: I was moving toward it at nearly 50 mph. Yet the feeling that eclipsed all others was a profound vulnerability—that I was exposed. And I was. High divers do not wear protective padding; they wear swimsuits. You are completely unprotected.

Regardless of how genetically predisposed a person is to taking risks, risk-taking success is contingent upon a good fit between the risk and the risk-taker. The risk-discerning question “Is this the right risk for me?” is one of compatibility. Right risks are often those that offer the potential to fill our gaps. Behind every right risk is the right reason, and successful risk-takers take the risks they do because the risks complete them in some way. Making those 1500 leaps off the high-dive platform taught me that risk-taking is not about seeking thrills, it is about seeking fulfillment.

Leadership and RiskAs a leader, it is important to be willing to take risks. But how do you know if a risk is worth taking? Here are a few things to consider:

What are the potential rewards? What could you achieve if the risk pays off?What are the potential consequences? What could go wrong if the risk doesn’t pay off?How likely is it that the risk will pay off? What is the probability of success?What is the cost of failure? What will be the cost if the risk doesn’t pay off?If the potential rewards outweigh the potential consequences, and the probability of success is high, then the risk may be worth taking. However, if the potential consequences are too great, or the probability of success is too low, then it may be best to avoid the risk.

The risk you chose to take might not be a risk to others. The right risk gives you something to take away from an experience. The right risk leaves you better than you were.

A lot of people ask me, “How did you get interested in the virtue of courage?” My answer? It actually started with a profound fear! And choosing to overcome that fear and take the risk made all the difference for me.

Do you have something holding you back in your career or life? What is a right risk that could fill the gap between where you are and where you want to be?

This post is based on an excerpt of Right Risk: 10 Powerful Principles for Taking Giant Leaps with Your Life.

The post Taking the Right Risk as a Leader appeared first on Giant Leap Consulting.