The Paris Review's Blog, page 832

April 8, 2013

Paula Fox, Work in Progress

New Emotion: On Kirill Medvedev

In 2006, a leading Moscow publisher issued Texts Published Without the Permission of the Author, comprised of the works of a well-known Russian poet. Rather than a lawsuit, the book resulted in a literary symposium, accompanied by a debate about the nature of copyright and, finally, the first translation of Kirill Medvedev’s works into English. In December 2012, It’s No Good: poems/essays/actions—a compilation of the thirty-seven-year-old poet-activist’s work—was published, indeed, technically without the permission of the author, by n+1 and Ugly Duckling Presse.

In 2006, a leading Moscow publisher issued Texts Published Without the Permission of the Author, comprised of the works of a well-known Russian poet. Rather than a lawsuit, the book resulted in a literary symposium, accompanied by a debate about the nature of copyright and, finally, the first translation of Kirill Medvedev’s works into English. In December 2012, It’s No Good: poems/essays/actions—a compilation of the thirty-seven-year-old poet-activist’s work—was published, indeed, technically without the permission of the author, by n+1 and Ugly Duckling Presse.

Medvedev, a controversial figure in the contemporary Russian poetry scene, stopped publishing in 2003. He would continue to release poetry, essays, and calls to political action on his Web site, LiveJournal, and Facebook page. But he renounced all rights to his own work. “I have no copyright to my texts,” he wrote in Manifesto on Copyright, “and cannot have any such right.” He became more deeply involved in leftist activism. Some thought him washed up, a has-been, even crazy. Others were angered by what they deemed a gimmick.

Critical of the post-Soviet liberal intelligentsia, makers of the culture who came to dominate an increasingly booming nineties Russia, Medvedev—who was born in Moscow in 1975—and his work issue directly from the tradition he critiques; his father was a well-known post-Soviet journalist. A decisive moment of separation might be found in his abdication of the most basic literary right. Read More »

These Quizzes Are Hard, and Other News

Can you guess these classic books from their phantom covers? In a word: no. (Well, three of them.)

Guess these famous novels from their second lines? We batted like .600.

Also disspiritingly difficult: this John le Carré quiz.

Buck up! “Without the advertising budgets of major houses, the smaller presses have more difficulty finding readers, Mr. Nelson said, and the idea behind the library was to form a community of people who could share books that were not easy to find elsewhere.” Meet Mellow Pages Library of Bushwick.

Iain Banks, who announced last week that he is dying of cancer, married his long-term partner at Inverlochy Castle Hotel in the Scottish Highlands. As he put it, he asked if she would “do me the honour of becoming my widow.”

April 5, 2013

Alejandro Zambra, Santiago, Chile

A series on what writers from around the world see from their windows.

I’m not sure that my little studio is the best place in the house to write. It’s too hot in summer and too cold in winter. But I like this window. I like those trees crossed by power lines and that slice of available sky. The silence is never absolute, or maybe it is—maybe my idea of silence now includes the constant barking of dogs and the uneven roar of motors. I take enormous pleasure in watching passersby, the odd cyclist, the cars.

When the writing isn’t happening I just sit there, absorbing the scenery, adoring it. I’m sure those minutes, those apparently lost hours, are useful in some way, that they’re essential for writing: that my books would be very different if I had written them in another room, looking out another window. —Alejandro Zambra

Translated from the Spanish by Harry Backlund.

Paula Fox and the Gift of Understanding

This year our Spring Revel will take place on April 9. In anticipation of the event, the Daily is featuring a series of essays celebrating Paula Fox, who is being honored this year with The Paris Review’s Hadada Prize.

This year our Spring Revel will take place on April 9. In anticipation of the event, the Daily is featuring a series of essays celebrating Paula Fox, who is being honored this year with The Paris Review’s Hadada Prize.

When I saw the film adaptation of The Hunger Games last year, I left the theater feeling uneasy about the shaky-cam, blurry, PG-13–sanctioned violence of kids killing kids. It was videogame violence, the sort that disappeared in the span of a moment, not the sort of savagery that hits you in the gut, makes you understand what the cost of violence can be. Weeks later, the film did not sit well with me, lingering as a mediocrity only made palatable by the endless soul of Jennifer Lawrence’s presence onscreen.

And after rereading Paula Fox’s The Slave Dancer, a 1974 Newbery Award–winning children’s novel, I wonder, seriously, what she would make of the glib work aimed at children these days, particularly the uneven aspects of the Hunger Games series—on book and film—a work that puts its characters in thrilling situations and often on the precipice of horrible choices that will define their humanity, but all too often stops and takes the easy way out, in the form of deus ex machinas and conspiracies that go all the way to the top.

Because here’s the thing about Paula Fox’s work: she never takes the easy way out. And in her work for children, she writes with evenness and truth, never lying to children about the horrors of the world. Rather, she gives them the chance to find some light on the other side. Read More »

What We’re Loving: Smells, Films, and Flames

It is wrong to kvell, but according to both Adam Shatz and Yasmine El Rashidi, our poetry editor, Robyn Creswell, has knocked it out of the park with his translation of Sonallah Ibrahim’s modern Egyptian classic That Smell and Notes from Prison. Unlike writers better known in the West, says El Rashidi, Ibrahim “has continuously reinvented the form and language he uses in his work, while probing deeply into the underlying tensions running through Egyptian society. Creswell’s new translation of the novel finally allows English language readers to appreciate these qualities … Despite the differences of syntax between Arabic and English, the translation retains the tone, the vocabulary, and the pared down and staccato rhythm of the original.” We take her word for it. —Lorin Stein

It is wrong to kvell, but according to both Adam Shatz and Yasmine El Rashidi, our poetry editor, Robyn Creswell, has knocked it out of the park with his translation of Sonallah Ibrahim’s modern Egyptian classic That Smell and Notes from Prison. Unlike writers better known in the West, says El Rashidi, Ibrahim “has continuously reinvented the form and language he uses in his work, while probing deeply into the underlying tensions running through Egyptian society. Creswell’s new translation of the novel finally allows English language readers to appreciate these qualities … Despite the differences of syntax between Arabic and English, the translation retains the tone, the vocabulary, and the pared down and staccato rhythm of the original.” We take her word for it. —Lorin Stein

On paper, Sarah Polley’s documentary Stories We Tell and Shane Carruth’s Upstream Color could not be more different, but they made for a nice double feature this past weekend at New Directors/New Films. Both films raise questions about identity and the ownership of memory. Both throw conventional narratives out the window. And when I walked out of each, not all my questions were answered, but maybe that’s the point: life’s complex, and some things unanswerable are still worth exploring. —Justin Alvarez

In Lars Iyer’s Exodus, the friendship between two minor academics, Lars and W., is founded not on shared interest but on a shared sense of failure, self-laceration, and gin. Together Lars and W. bemoan the state of the academy and the seeming impossibility of philosophy, but I laugh loudest when W. bemoans the state of Lars: “‘The true and only virtue is to hate ourselves,’ W. says, reading from his notebook. To hate ourselves: what a task! He’ll begin with me, W. says. With hating me. Then he’ll move on to hating what I’ve made him become. What I’ve been responsible for. Then—the last step—he will have to hate himself without reference to me at all.” For even more Lars and W., also read Spurious, the first book in Iyer’s trilogy. —Brenna Scheving Read More »

Moist, and Other News

“Other books I can’t throw away because—well, they’re books, and you can’t throw away a book, can you?” In memory of the late Roger Ebert, an essay on libraries and love.

Amazon is in the process of testing an automated cover generator. Well, of course they are, silly.

Why do so many people hate the word moist, anyway? On word aversion.

Lizzie Skurnick, the Boswell of the world of YA literature, is launching Lizzie Skurnick Books, an imprint that will “bring back the very best in young adult literature, from the classics of the 1930s and 1940s, to the thrillers and social novels of the 1970s and 1980s.”

Short version: Scotland is giving back some of George Washington’s books.

April 4, 2013

Lady Liberty

Alexandra Socarides of The Los Angeles Review of Books’s has a lovely and informative piece on “New Colossus,” the Petrarchan Emma Lazarus sonnet that famously adorns the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty. We learn about the poet and the poem’s formal and political import; Socarides frames “New Colossus” as a bold statement for immigrant reform and tolerance, Lazarus herself as an engaging figure worthy of study.

Alexandra Socarides of The Los Angeles Review of Books’s has a lovely and informative piece on “New Colossus,” the Petrarchan Emma Lazarus sonnet that famously adorns the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty. We learn about the poet and the poem’s formal and political import; Socarides frames “New Colossus” as a bold statement for immigrant reform and tolerance, Lazarus herself as an engaging figure worthy of study.

My own history with the iconic poem is less exalted. I remember distinctly the first time I heard it: I was three years old, in bed with one of the migraines that had arrived with the news of my mother’s pregnancy with a new brother. My father read me the poem, his voice choked with emotion, explaining that it had heralded my great-grandparents’ arrival in New York. Then he left me to sleep, drugged with pain and the red liquid children’s Tylenol that always stained the sheets.

When I woke up a few hours later, cautiously better, the words were still in my head. “Yearning to breathe free …” I thought.

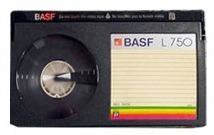

I wandered into the other room, where my parents were sitting on the bed with my new baby brother, hideous and red-haired. My father was making a videotape with his Betamax camera, not that the baby was doing anything interesting. I casually stripped off my cotton underpants, lay down on the bed, and began kicking my legs in the air.

“Look at me!” I said. “Look at me!”

“Sadie, put on your underpants,” said my mother.

“But, Mama!” I cried. “I’m yearning to breathe free!”

The baby rolled or something.

“MY VAGINA IS YEARNING TO BREATHE FREE!” I shouted, in case they’d missed it.

“Today, Charlie is four months old,” my dad was narrating. “We are on Seventy-Sixth Street. Sadie, would you like to say something to the camera?”

“Camera!” I screamed. “MY VAGINA IS YEARNING TO BREATHE FREE!” I waved my legs in the air vigorously.

“Anything else?”

“MY VAGINA—”

“Enough with the vagina, Sades,” said my dad.

This is all on videotape. I recently saw it when I took a bunch of Beta tapes to be digitized. I apologize to Emma Lazarus.

*

Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name

Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand

Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command

The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

Master Class

The packet came in the mail. My first MFA workshop would be led by Lynne Sharon Schwartz. So I did what any good writing student does: I bought and read one of her books. I remember humming along through Disturbances in the Field, deeply engaged with Lydia, a Manhattan pianist who understands her life through the lessons of the great philosophers. “Heraclitus was right,” she says. “No sooner is a position established than it erodes. The solid earth under our feet melts into water, evaporates into air, and is consumed in fire. I moved from one family to another.” The mood is heady, the details exquisite. Here, I thought, is a novel unhampered by plot: a capacious, intelligent book about the endless trouble of being smart and a woman, of being with other people and alive. A book that showed me how to write sentences, and how to live a life of the mind. Twenty-three in Brooklyn, I took constant, exuberant notes.

The packet came in the mail. My first MFA workshop would be led by Lynne Sharon Schwartz. So I did what any good writing student does: I bought and read one of her books. I remember humming along through Disturbances in the Field, deeply engaged with Lydia, a Manhattan pianist who understands her life through the lessons of the great philosophers. “Heraclitus was right,” she says. “No sooner is a position established than it erodes. The solid earth under our feet melts into water, evaporates into air, and is consumed in fire. I moved from one family to another.” The mood is heady, the details exquisite. Here, I thought, is a novel unhampered by plot: a capacious, intelligent book about the endless trouble of being smart and a woman, of being with other people and alive. A book that showed me how to write sentences, and how to live a life of the mind. Twenty-three in Brooklyn, I took constant, exuberant notes.

But then, halfway through, like a guillotine, the plot falls into place. Something irreversible occurs in Lydia’s life, something devastating. And despite the book’s description, despite the many, many narrative clues, I was shocked. Suddenly, I had in my hands an entirely different book. The armor of ideas Lydia had been forging no longer fit the shape of the world; somehow, she’d have to recast it. Schwartz was even more masterful than I’d thought.

Mildly daunted, I made my way to Bennington, where I met the author herself: a small, dignified woman who clearly didn’t suffer fools. Somehow, I managed to call her Lynne. As a teacher, she turned out to be quite compatible with her book: broad-minded yet blunt, rigorous yet humane. Unsurprisingly, she’d read everything—because, as she often insisted, the only way to become a writer was to read and live and write. Like Lydia, she could always call up just the right book for any situation.

Lynne wasn’t the first writer I’d known, but she may have been the first with whom I kept up a regular correspondence. I learned recklessly from her recommendations, and from her own books, too. In her memoir of bibliophilia, Ruined By Reading, she cautions that “the writer is born of our fantasies. Reading her book, we fashion her image, which has a sort of existence, but never in the flesh of the person bearing her name.” And yet, I really did know this person, which had to count for something. We traded childhood stories, discovered a mutual affection for Daniel Deronda and Natalia Ginzburg, shared news of births and deaths. She was known as one of the bad cops at Bennington, famous for being tough on her students. Well, if this was bad, I wouldn’t waste my time with good. Read More »

They Don’t Love You Like I Love You

In seventh grade, we read The Catcher in the Rye. One day, Ms. C. handed out xeroxed maps of New York City and asked us to trace Holden Caulfield’s path through New York. We did. “Do you see the pattern?” she kept asking excitedly. “Do you see what it’s all pointing to?” No one did. “He’s heading home! He’s circling around home!” she finally shouted, exasperated. We were collectively underwhelmed. I suspect Holden Caulfield might have been, too.

Maybe our teacher was onto something, though: in a sense, she was urging us to do the same thing Becky Cooper conceived of in her collaborative art project Mapping Manhattan, now collected in a book. A range of New Yorkers—artists, writers, thinkers, kooks—present maps colored (in some cases literally) by their personal experiences. The results are as wide-ranging and fascinating as one might expect. None, that I can see, are leading to the author’s childhood home—but then, if memory serves, I only got a B+ in that class.

Malcolm Gladwell’s map.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers