The Paris Review's Blog, page 830

April 15, 2013

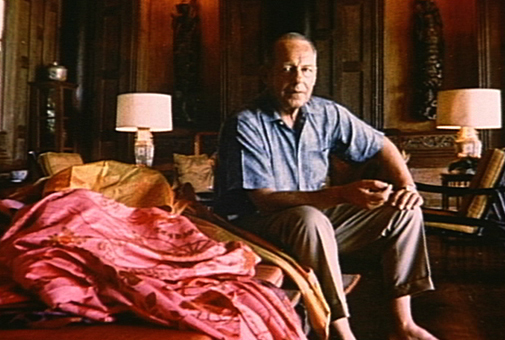

Silk Thread: The Strange Mystery of Jim Thompson

In the study of the Jim Thompson House & Museum in Bangkok, just above Thompson’s old desk, are two separate horoscopes, foretold and framed, hanging on the wall. One of them predicts good luck in 1959, the year Thompson chose to move into this house, retired from the U.S. Army and the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), having already relocated to Bangkok and gotten rich revitalizing the Thai silk industry. The other horoscope included in the frame predicts bad luck at the age of 61 for he who was born in the Year of the Horse. Thompson had been born in the Year of the Horse, and in 1967, at the age of 61, he went for a walk in the woods of Malaysia just south of here and never came back. Not even his remains have ever been found.

Thompson’s house is now a museum, although during his lifetime this city would never have accommodated such a thing. He perfected a popular silk that was better than other silks—a silk cut from lengthier cloths and colored by stronger and faster-acting and better-varied dyes. When it was chosen for all the silks used in the movie version of The King and I (1956), it became more popular still. At the time, Thailand had given up on its own silk industry, importing a cheaper fabric from other countries. The localized empire Thompson established would improve the lives of Bangkok’s citizenry, handsomely employing them in a business benevolently run. Still, his enemies were legion, and they extended all the way up into society’s highest strata. The mystery of just why and how Thompson disappeared, and by the agency of whom, is one that persists still and probably always will.

Read More »The Most Expensive Book in the World, and Other News

This is the most expensive book in the world.

“Because the Pulitzer board couldn’t possibly be so cruel two years in a row, right?” We shall see.

We have a title: the new Bond novel is called Solo.

Neil Gaiman left a little guerrilla artwork on the New York streets.

Julian Barnes: England “has always been a comparatively philistine country.”

April 13, 2013

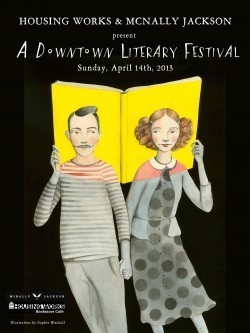

See You There: Paris Review at the Downtown Literary Festival Tomorrow

Join The Paris Review tomorrow for McNally Jackson and Housing Works Bookstore’s inaugural Downtown Literary Festival, a daylong celebration of New York City’s literary culture. The festival will take place at both bookstores simultaneously throughout the day, followed by a happy hour mingle at Housing Works Bookstore and an after-party at Pravda, featuring Russian literature–themed cocktails.

Join The Paris Review tomorrow for McNally Jackson and Housing Works Bookstore’s inaugural Downtown Literary Festival, a daylong celebration of New York City’s literary culture. The festival will take place at both bookstores simultaneously throughout the day, followed by a happy hour mingle at Housing Works Bookstore and an after-party at Pravda, featuring Russian literature–themed cocktails.

We will present selections from The Paris Review’s archives, with readings of the poetry of Barbara Guest and Bernadette Mayer by Hettie Jones, Jim Carroll’s The Basketball Diaries by Hailey Gates, and a performance of Jack Kerouac’s 1968 Art of Fiction interview by Paul Lazar, of Big Dance Theatre.

Fast Talking: Downtown Writing from The Paris Review Archive

Sunday, April 14, 1 P.M.–1:45 P.M.

McNally Jackson

52 Prince Street

April 12, 2013

Animal Farm Timeline

Cover of Snowball’s Chance, 2002. Cover of Why Orwell Matters, 2002.

Timeline to this Timeline

September 9, 2011, I’m walking down Lafayette Street with my wife. We’re close to my apartment, with the Tribeca sky, the sky of my youth, hovering above our destination. I have a title idea. “Snowball’s Chance,” I say, “there’s something to it.” She isn’t so sure.

Then, 9/11. Then, 9/13, I understand the title. Animal Farm. Snowball returns to the farm, bringing capitalism, which has its own pitfalls. I’ll turn the Cold War allegory on its head—apply Orwell’s thinking to what had happened in the fifty years since the end of World War II. Three weeks later I have a clean draft.

I start to think about publication, and run into a bump: the feeling in the publishing world, in the entertainment world, is that parody is about to lose its protected status in the United States. Several major lawsuits are underway (2 Live Crew, The Wind Done Gone), copyright has been extended indefinitely for major corporations, and the Supreme Court has never looked more conservative. Given the climate, and that parody is not protected in the United Kingdom, the Orwell estate announces itself “hostile” to my manuscript. The book is nevertheless released in 2002 (by a small but longstanding press, Roof Books), and supported in part by a state grant. At the same moment I see fit to attack Animal Farm as a Cold War allegory—an allegory that I see as conservative, xenophobic, and a bludgeon for radical thinking—Christopher Hitchens, who has taken a sharp turn to the right, sees the need to defend it. In Why Orwell Matters, also published in 2002, Hitchens attempted to apply Orwell’s later-life “Cold War,” a term he popularized, to a stance against terrorism. The media picks up on Hitchens, and Snowball as a counterpoint, and the books are accordingly praised or derided.

1879–1880

Nikolai Kostomarov, Stamp of Ukraine, 1992.

Nikolai Kostomarov (1817–1885) pens his story Animal Riot, a farmyard allegory that takes as its analog a hypothetical Russian revolution. A century later, in 1988, the English-language Economist will compare Kostomarov’s 8,500-word story to George Orwell’s 20,000-word Russian Revolution allegory, Animal Farm (which, unlike Animal Riot, ends badly), finding numerous points of comparison. For example, a bull in Animal Riot:

What We’re Loving: Aliens and Birds

“Repressed Soviet writers had the chance to become political heroes, even when (as in the case of Joseph Brodsky, for instance) their writing was not explicitly political. Every ‘unofficial’ story or poem became an act of bravery, of protest. Illicit literature was circulated among friends and smuggled abroad; the sheer effort devoted to reading and sharing samizdat texts was a testament to their significance. America has its share of homegrown graphomaniacs, hellbent on becoming the next John Grisham or Jonathan Franzen, but it’s just not the same.” In The Nation, our frequent contributor Sophie Pinkham asks what happened to Russian writing. —Lorin Stein

Lately I have been returning to the work of John Thorne. Thorne, who has published an idiosyncratic and resolutely un-foodie newsletter for thirty years, is acknowledged in the trade to be one of our finest food writers. I think he’s one of the best essayists working, full stop: humane, eccentric, incisive. Start with his book Simple Cooking, although you can’t really go wrong. As Thorne writes in his essay “Perfect Food,” “Our appetite should always be larger and more curious than our hunger, turned loose to wander the world’s flesh at will. Perfection is as false an economy in cooking as it is in love, since, with carrots and potatoes as with lovers, the perfectly beautiful are all the same; the imperfect, different in their beauty, every one.” —Sadie Stein Read More »

One Word: bookBot

Neologism, we should say. Whatever you call it, the device—a robotic book delivery system—is just one of many nifty features at North Carolina State University’s James B. Hunt Library of the future. Check it out here.

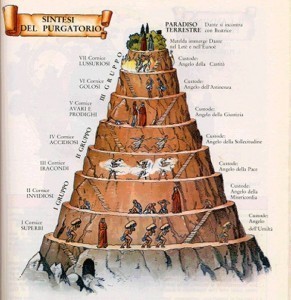

Men, Women, Dante, and Other News

GQ suggested the books every man should read.

So then Flavorwire amended their list.

You could, of course, also stick to Robert Frost’s favorite books. (If you like the classics.)

Women, meanwhile, get stuck with awful titles.

“Dan Brown’s forthcoming Inferno, of which Dante will be the central subject, has already got me trembling. Brown might have discovered that the Divine Comedy is an encrypted prediction of how the world will be taken over by the National Rifle Association. When the movie comes out, with Harrison Ford as Dante and Megan Fox as Beatrice, it will be all over for mere translators.” Clive James, by the book.

April 11, 2013

Laughing in the Face of Death: A Vonnegut Roundtable

“Birds were talking. One bird said to Billy Pilgrim, ‘Poo-tee-weet?’”

—Slaughterhouse-Five, by Kurt Vonnegut

A well-constructed e-mail and some guts on my part had one day inspired Harold Bloom to send me the phone number of his editor. A few days later I began writing for his literary criticism series with what was then Chelsea House and what is now Infobase Publishing. I put together two works on Tennessee Williams and a revamp of a guide to Conrad’s Heart of Darkness before I was contracted to write a book called How to Write About Kurt Vonnegut. Most of what I had read of Vonnegut’s work I had read long ago, and I had seen Vonnegut only once at a forum in Connecticut in 2006, where he appeared onstage with Joyce Carol Oates and Jennifer Weiner, the three of them parodying a dysfunctional family in a scene that led to much laughter. The theater, however, was completely absent of sound when an audience member asked a cultural-political question and Weiner sputtered, “I wasn’t expecting to have to deliver a message about humanity tonight.” “Well, leave,” was Vonnegut’s response. It was this Vonnegut moment that featured prominently in my mind’s reel as I packed notebooks, an inordinate number of pens, and several of Vonnegut’s novels in my bag that July in preparation for a trip to Boston. Once there, I read and took notes on one Vonnegut book per day from my room. (The hotel that I checked into, the Liberty, had served as a jail until a revolt over poor inmate conditions in the early 1970s led to its obsolescence and subsequent evolution into luxury accommodations.)

When I got tired of being cooped up I moved to the lobby, where I witnessed absurdities such as a woman pushing a very small dog in a stroller and smiling, goofing tourists wandering the open tiers of what had once been rows of jail cells, and sometimes I wandered up Charles Street and popped into the local antique stores. I couldn’t afford most of what was in them, but haggled in one shop over the purchase of an antique blue-and-white tile which featured a single bird—a bluebird. It was a difficult trip, hot and coming on the tails of a year in which nothing went as planned and which involved the full stock and variety of deaths that is possible in one human year. And so I had to have this tile (symbol of happiness, you understand), and I turned over my last ten dollars to acquire it, and I read each book that week with the tile tucked away next to me, wrapped in paper in my bag. And in the strange, beautiful ways that life and art—life and fiction—can converge, I became certain that I was now living in a Vonnegut novel, filled with dark and strange humor and impossible—weren’t they? shouldn’t they be?—absurdities. The only highlight of the trip was an evening concert, one of Beethoven’s symphonies played live by the Charles River, and I sat on the ground listening with my pants growing damp from the remnants of a recent downpour. “Music,” Vonnegut said, “makes practically everybody fonder of life than he or she would be without it.” But I wasn’t feeling fond, and I returned home having worked hard but defeated. I put the tile away on one of my bookshelves. It wasn’t until one day—after I had finished the book and had grown tired of burdens and hungry for laughter—that I saw it again. I had placed the tile so that the bird was caught in an endless nosedive. And look at its tail! What had made me think that it was a bluebird? It had the tail of a peacock! With it seeming like the natural thing to do, I turned it so that its beak was pointed skyward, so that this strange bird—a bluebird with the tail of a peacock—was now a triumphant phoenix. A ridiculous bluebird-peacock-phoenix. The summer had ended and so had the heat. And things had gone on. Poo-tee-weet.

On the eve of the anniversary of Vonnegut’s death, I asked Ben Greenman, David Holub, Rick Moody, Josip Novakovich, and Avi Steinberg about their own memories of Vonnegut’s work and about why everyone else should remember it, too.

How has Vonnegut influenced or informed your own work?

Ben Greenman: Through moral rigor, though not in any of the predictable ways. As a younger reader, which is when I had my strongest connection to Vonnegut—maybe not my most meaningful, but my strongest, in the fashion of first love—I took a preteen tour through Mother Night and Slaughterhouse-Five and Cat’s Cradle. The things that I dimly and germinally felt about war and technology and religion and the different—but similar—risks to humanity inherent in all of them were laid out quite clearly. As time has moved along, the sources of the risks have shifted slightly, for purposes of camouflage, but the risks remain. Read More »

This Is a Bookstore

It was a church: the thirteenth-century Boekhandel Selexyz Dominicanen in Maastricht, Netherlands, to be exact. Converted and restored in 2007, it is now a fully-functioning bookstore, complete with coffee shop. See more pictures here.

Charlotte Brontë Poem at Auction, and Other News

An itty-bitty, handwritten Charlotte Brontë manuscript has sold at auction for £92,000.

In Hong Kong, one small bookstore has become a haven for banned Chinese books.

The City of New York is ponying up $230,000 to pay for the Occupy Wall Street Library destroyed in the 2011 Zuccotti Park raid.

With numbers dwindling, a Texas book club folds after 120 years of regular meetings.

I hereby call for a moratorium on … whatever this genre is.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers